1. Introduction

[1.1] On Main Street, U.S.A. at Disney's Magic Kingdom in Florida, there are some rather covert signs that read "Heroes Needed!—Enlist at the Firehouse." Next to City Hall in Town Square sits an unassuming firehouse with a banner strung across the top that invites guests to discover the community event where "Professor Merlin Reveals His Latest Sensation!" Just inside the entrance is another banner: "Secret Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom Recruitment Center" (figure 1). The firehouse is easy to miss, as are the Mystic Portals (projected screens) hidden throughout five lands of the theme park, which only appear when activated. Less hidden, however, are the sorcerers (other guests) walking around, tapping key cards to magic boxes, standing on the Circles of Power, listening to stories, and holding up playing cards when the animated portals prompt "Cast Your Spell!" Unaware visitors might look at these sorcerers and portals with curiosity, and children are often enthralled by a dormant piece of architecture suddenly erupting with Disney heroes and villains. Whether curious or enthralled, the reaction is likely to indicate that something different or remarkable is occurring. This attraction appears as a tangible implementation of the magic so often discussed in Disney rhetoric. The game also represents a shift in the theme park landscape, where guests have become a more active part of the storytelling fabric.

Figure 1. The banner in the firehouse on Main Street. Photograph by author, February 2016. [View larger image.]

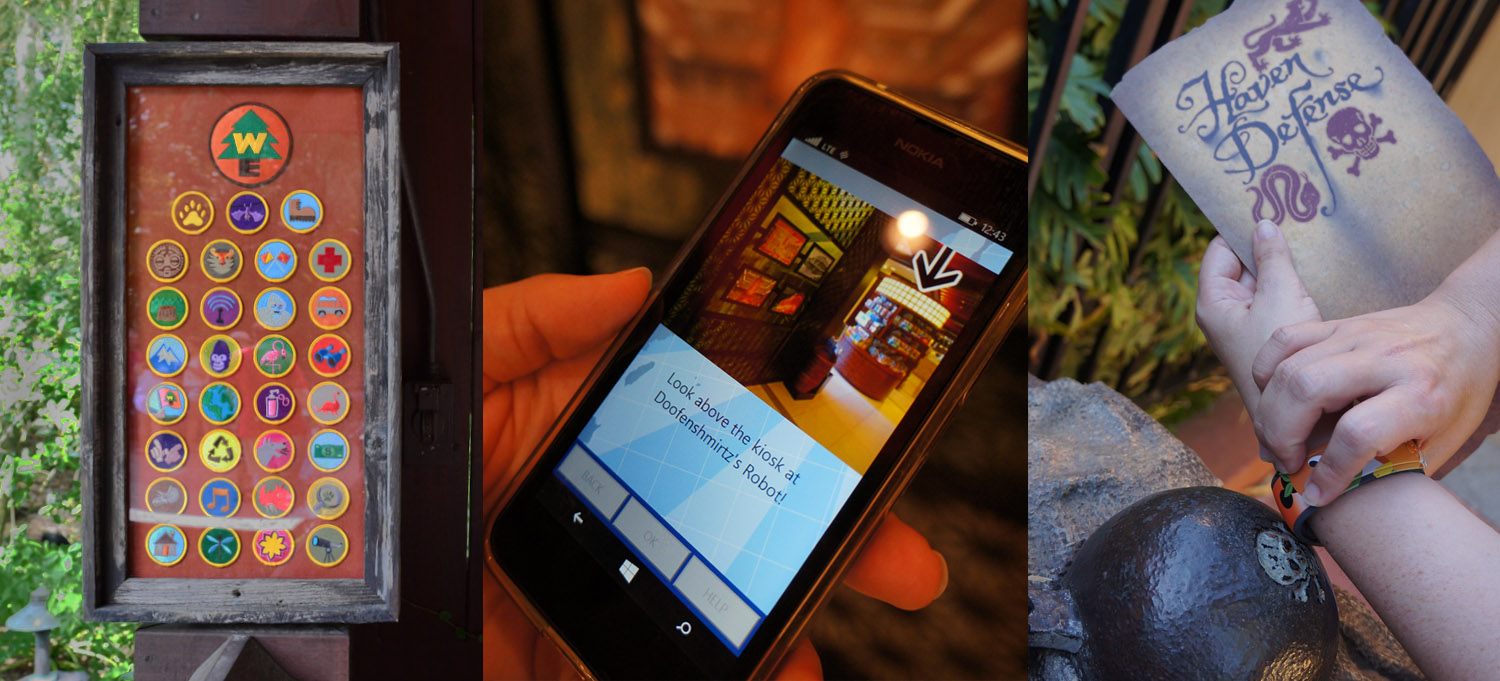

[1.2] Theme parks have undergone changes over the years. Previously, the emphasis was often on more passive experiences; as engaging as the most classic rides at Disney are (Pirates of the Caribbean, Haunted Mansion, It's a Small World, etc.), they are essentially guests sitting back and watching a story unfold around them. Now, passive rides have evolved into ones featuring interactivity and immersion, often making use of new technologies. These are more active attractions with an emphasis on guests "becoming participants" (Niles 2016) or even taking the lead role in the adventure. This is a significant shift, as attractions have traditionally been spectacles or have employed different notions of interactivity (e.g., Jungle Cruise skippers joking with guests on board or multiple Frozen-based sing-along shows). Perhaps because of the prominence of video games and other interactive media in contemporary society, these kinds of technology-mediated interactive experiences have emerged in the theme park attraction mix. Many amusement and theme parks have added interactivity by way of competitive rides where guests shoot at targets, but the number of interactive quest games is increasing. At Walt Disney World alone, several physical quest-type attractions are currently running that fit the thematic tendencies of their parks (figure 2): Wilderness Explorers (Disney's Animal Kingdom), a fully physical, educational game with scout-style badges; Agent P's World Showcase Adventure (Epcot), a spy-type adventure utilizing a cell phone interface; A Pirate's Adventure (Magic Kingdom), a mostly physical treasure hunt with special effects; and Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom, an integration of physical sets and technological mediation. Many interactive elements, games, story enhancements, and even customized messages to guests have been added to queues and attractions throughout Walt Disney World. Additionally, events throughout the year (e.g., Easter, festivals at Epcot, school groups, hotel stays, and even one-off events like the launch of the Lion Guard television series) have sparked the creation of scavenger hunt games. Walt Disney World's expansive high-technology system, MyMagic+, brings interactivity to ride and restaurant reservations. All of these integrations of technology and interactivity represent the theme park moving into this generation and reimagining the notion of the attraction to include "individualized interactive spatial narratives" (Koren-Kuik 2013, 152).

Figure 2. Walt Disney World quests (from left to right: Wilderness Explorers, Agent P's World Showcase Adventure, A Pirate's Adventure). Photographs by author, April 2016. [View larger image.]

[1.3] The most complex of these interactive adventures, Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom (SotMK), opened in 2012. It features the guest in the role of a sorcerer attempting to thwart the villain Hades, who has enlisted the help of nine other baddies from various Disney animated films to take over the theme park. The beginning sorcerer is given a map of all the portals, an RFID key card to activate the portals, and a pack of five spell cards. Players begin on easy mode but can advance to medium or hard if they complete the game. In total, there are over 70 collectible cards with Disney characters on them. These cards range from common to rare; the majority of them are free, but some cards are only available by purchasing tickets to special events or by buying sets of cards that include a rare lightning card. Easy mode can be completed with any cards, but the more difficult modes involve knowing villain weaknesses and creating combinations of spells. The richness of this game and the uniqueness of the experience have encouraged multiple audiences to play and inspired a fan culture. This in turn has added to fan-led practices that continue to help shape the theme park space.

2. Business decisions

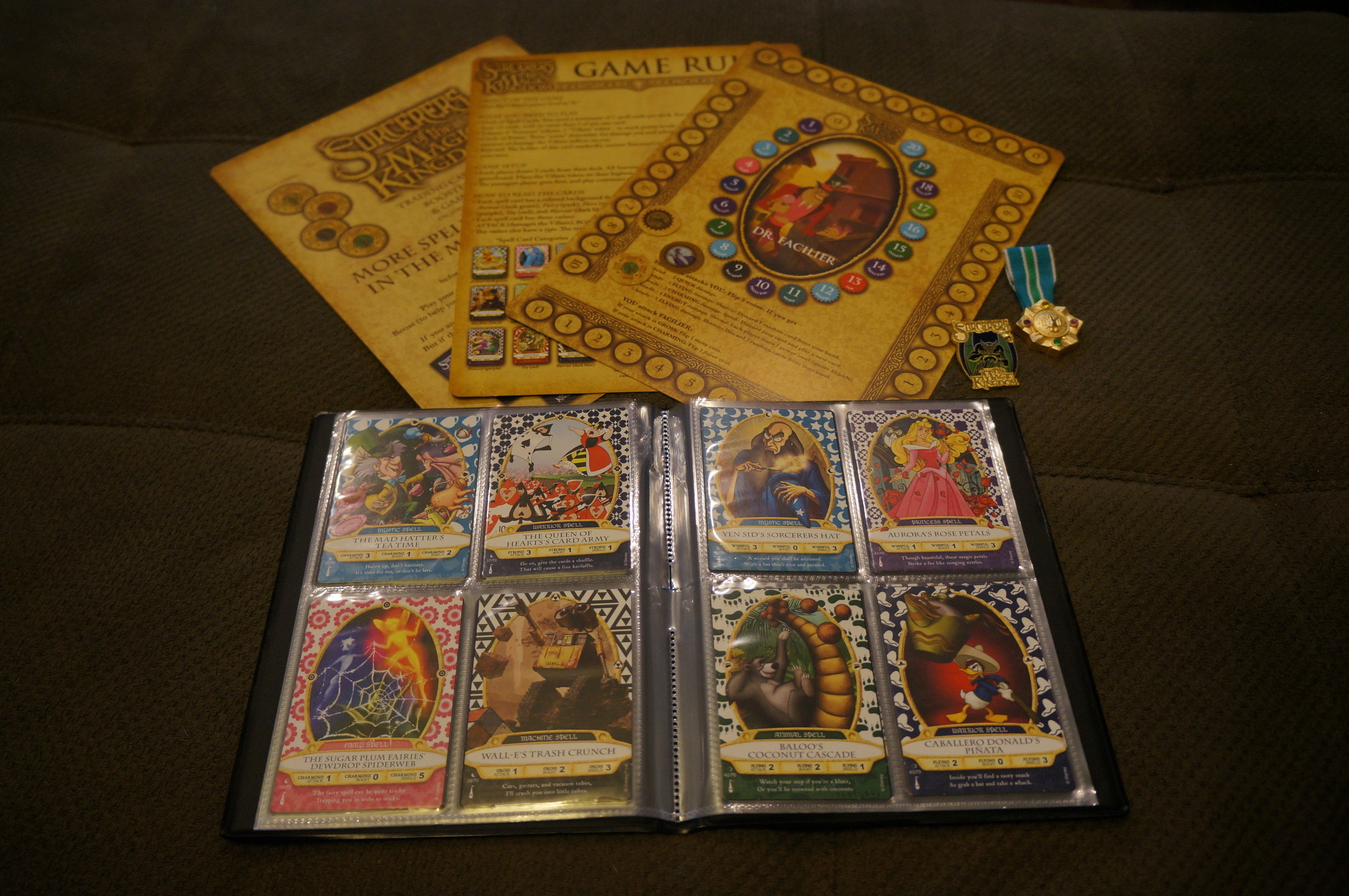

[2.1] The first constituent in the change of park space is management. Despite the creative ventures going on at theme parks, they still tend to make decisions that benefit the business. In the case of a game like SotMK, there are probable reasons why executives decided to fund it: distribution of crowds at the Magic Kingdom (the most visited theme park in the world), repeat visitation (the holy grail of theme parks), enhancement of brand loyalty (through engagement with multiple film properties), unit synergy (between Studio Entertainment and Parks & Resorts), and related item profit (pins, power-up shirts, spell card binders, rare cards, the paper version of the game, and perhaps food and beverage during extra visits) (figure 3). Guests partaking in these quests are presumably less likely to spend time in lengthy attraction queues and more likely to purchase products. There are then both tangible and intangible benefits of having attractions like this.

Figure 3. Master Sorcerer shirt: merchandise item, in-game power up, and fan identification. Photograph by author, April 2016. [View larger image.]

[2.2] There are a few forms of control built into the game. Management represents the first level of control. The park schedule dictates the operating hours of the attraction each day. In addition, creators built in a system that routes players to specific portals so that crowds do not build up at each one. Portals are networked and can be circumvented completely with the system ready to cut off a segment of the story, bypass a portal being fixed, or skip an entire land during busy times or events. Like with other systems at the park (e.g., FastPass+, daily parade and show guest control facilitation), the portals are part of a design that ensures both proper guest flow patterns and the accustoming of visitors to these patterns. Attractions like SotMK assist efficiency as much as creative or aesthetic standards. Most video games do not have the added complexity of managing people in a physical space. Despite a system that "actively distributes people to where they should be," however, it cannot account for, as the lead designer deems it, "human free will" (Ackley quoted in Brigante 2012). Guests can be told which portal to visit next, in other words, but they may choose to wait and do other things first, allowing for at least some deviation.

3. Creative explorations and controls

[3.1] Creative professionals in the themed entertainment industry work under budgetary, time, and other constraints including guest expectations. The lead designer of SotMK was Jonathan Ackley at Walt Disney Imagineering, a veteran game designer with an interest in "nontraditional, nonlinear storytelling" (Lewis 2012) who has experience with both older adventure games and other Disney quest projects. The group Creative Capers (2016) assisted with animating the game's scenes; on their Web site, they describe the challenge of animating "Disney's most iconic characters from ten beloved films" in addition to merging the settings of the films with that of the real park. SotMK is considered an "ambitious" and even "risky" project that took 4 years to create (Ackley quoted in Brigante 2012). As with all Disney attractions, the grounding of the attraction is story. SotMK has an overarching narrative that is a transmedia story of the synergistic variety (Jenkins 2006), though unlike transmedia stories with multiple channels, it is only accessible through the one medium of visiting the theme park (or through secondhand accounts on video). The creators had to determine a way for a story to work across multiple, differently-themed areas, so they chose a master villain, Hades, to enlist scoundrels from other animated Disney films to wreak havoc on the Kingdom. Merlin acts as the primary guide of the experience, urging players to "defend the realm" (figure 4). The use of Merlin as a (nonplayable character) mentor moving through worlds establishes some similarity to the popular Kingdom Hearts video game series (2002–) that has a comparable crossover fiction with Disney and other fantasy realms. Likewise, the mobile game Disney Magic Kingdoms (2016) positions Merlin in a similar way as a guide to help dispel dark magic. The films represented in the SotMK story are Fantasia (1940), Sleeping Beauty (1959), 101 Dalmatians (1961), The Sword in the Stone (1963), The Little Mermaid (1989), Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994), Pocahontas (1995), Hercules (1997), The Emperor's New Groove (2000), and The Princess and the Frog (2009). Villains, henchmen, protagonists, and sidekicks from the films are all present, and designers purposely selected canon movies from different Disney animation periods. The use of classic films, an unchangeable story, and determined video game structures (with specific objectives and ways to accomplish them) introduces another level of control into the game.

Figure 4. Merlin preparing new sorcerers. Photograph by author, February 2016. [View larger image.]

[3.2] SotMK is an officially-authorized crossover story that meets some Disney standards; it fulfills one of the purposes of the Disney theme parks: to allow fans to "engage with their favorite fictional worlds" (Koren-Kuik 2013, 146). While there are many villains, they maintain their traits from the original films. With the exception of Hades and Merlin, who move seamlessly between each story segment (as their magic abilities and powers might allow), the heroes and heroines of the films stay within their segments (e.g., Rafiki from The Lion King helps guide the guest through the subplot where Scar and the hyenas are the antagonists). In addition, the characters that seem to belong to a specific land stay in that land. The game can be played in Main Street, U.S.A., Fantasyland, Adventureland, and Frontierland/Liberty Square, and the villains align with these themes (Maleficent in Fantasyland, Jafar in Adventureland, etc.). Having traditional portrayals of characters upholds canon integrity but also places limits on fan imagination. Fans may expect this internal consistency and self-limit subversive possibilities. Marie Patrice Amon (2014) observes that the "reference texts" of Disney narratives "hold deep cultural recognizability and popularity based on narratives that are dogmatically consistent, with a predictably constant set of social values" (¶2.1). SotMK obeys these basic tenets. The characters are contained within the Magic Kingdom, a canon space, and they fit the archetype of good versus evil. The villains' motivations are conflated into one of desire for power; any deeper interrogations into the characters are unnecessary, as there is an expectation of familiarity with the stories. Furthermore, in Disney fashion, and probably as a result of the need for efficiency, it is impossible to lose the game. Unlike in many video games, performing poorly against a villain may mean losing a battle, but eventually the system relents to let the player win (after how many portals depends on the difficulty setting). The sorcerer rank will be lower with more lost battles, but the happy ending is ensured.

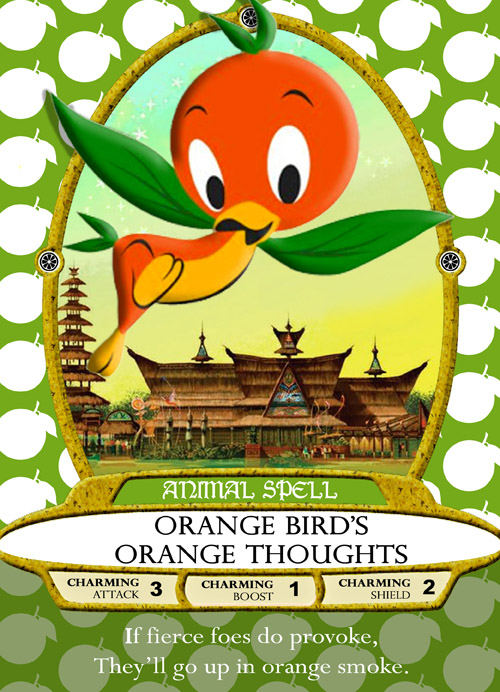

[3.3] Nonetheless, there are many transgressions of the canon. The first instance of this would be the presentation of all of the villains within the same world (ours, or at least the fantasy-reality space of the theme park). The story straddles the line between canon and fan fiction: canon, because it was created by Disney for a Disney attraction, but fan fiction, because it combines many villains and stories woven together into one crossover tale, a common fan fiction motif. In this way, SotMK is similar to the Kingdom Keepers (2005–) children's novel series from Ridley Pearson (published by Disney). In those books, the villains take over the parks and youth fix it; in the SotMK game, any park guest can be a sorcerer. Next, many of the villains who die (Maleficent, Ursula, Scar, Dr. Facilier) or are significantly transformed (Jafar, Yzma) in the films are all back in form at their peak of strength and evil. This may make sense because Hades is a deity with resurrection powers, but it is also quite a conceit that makes the core narratives seem unstable: are villains so easy to resurrect and transport into other worlds? At the game's conclusion, the villains are trapped inside of a crystal and are no longer deceased. SotMK is a kind of large-scale remix that the creators have utilized to facilitate a lengthier game with epic battles. These fictions complicate the notion of transmedia, providing a transfranchisal experience, or one that "bridges across multiple franchises" (Wolf 2014, xiii) but does not necessarily follow the internal logic of each film. Instead of merely a crossover plot, the game would be better characterized as an alternate universe that follows the logic of the theme park instead of the source movies. At the theme park, all of the characters exist at once in the same time and place. The time periods and places of the films no longer matter; meet and greets, parades, and shows mash them together. Villains live again, and a few characters remain suspended in earlier parts of their narratives (e.g., Ariel is still a mermaid, Rapunzel retains her long hair). There is tension present throughout the park between guest understandings of individual narratives and the timelessness of the park's story (something that removes story arcs and places characters in one landscape). Because the face characters especially are living and in a performance, they are imposed on the new space in the new time and maintain awareness of themselves as characters. Finally, the most significant element of gameplay, the spell cards, changes the story by expanding the universe. They "subtly shift the gaming experience," making it "less predictable" (Lewis 2012). While the story of Hades gathering the Crystals of the Magic Kingdom by means of various villains is set and unchanging (though the villains are usually in a different order each time), the collectible cards feature dozens of characters from Walt Disney Animation Studios, Pixar Animation Studios, and a couple of Magic Kingdom attractions. These cards interface with the portals, and the player chooses which ones to utilize for each villain (figure 5). Characters from, for instance, Bambi (1942) or WALL-E (2008) could thus be used to defeat villains from a completely different universe. More advanced players use combinations of multiple cards from any number of films in each land, continuously subverting thematic and narrative consistency. This highlights an important change of theme park narrative represented by the game: not only are guests in the story, they can also subtly influence their story version by the in-game choices of creative spells, though all choices may lead to victory.

Figure 5. Using a spell card against a villain. Photograph by author, April 2016. [View larger image.]

[3.4] Going beyond the stories within the game, the overall park's story has shifted with the introduction of a multiland narrative. The design of the castle parks including Magic Kingdom (and its older sibling, Disneyland) is such that each land is distinct. Instead of neatly delineated spaces, the SotMK player is forced to explore the lands and view the areas as a continuous narrative space (though each chapter is still within a defined area, and there are narrative and spatial transitions). Rather than a collection of attractions within a park container, experiences like SotMK turn the "entire park into an attraction" (Niles 2016, emphasis in original). While the story is built on well-known film properties, the other part of the tale is the Magic Kingdom itself, illustrating "location-based storytelling" (Lewis 2012). The general sense of aesthetics, peace, and uplift that visitors are theoretically supposed to enjoy when immersed in the fantasyscape is replaced by a mood of conflict and unrest. This works well in the role-playing realm, as many visitors already have emotional ties to the park or its narrative, so they will be more engaged in the sorcerer role. The game was also meant to be as unobtrusive as possible to nonplaying guests, so that their activities are unlikely to be disturbed by the game's presence (figure 6). The portals are often so seamlessly integrated into existing structures and theming elements that unaware park goers are even more intrigued to see sorcerers casting spells around the park. This functions in a similar way to Harry Potter Wands at Universal Studios, a spell-casting pursuit using wands instead of cards. Though it is an upcharge attraction that is more prominent and well advertised (as an essential part of the Wizarding World of Harry Potter experience), the Wands game is similar to SotMK in that guests playing the game interact with scenery, cast spells by means of a magical device, often dress the part (wizard robes or licensed shirts), face similar narrative inconsistency (inside the rides, guests are Muggles, but outside playing the game, they are wizards), and have preexisting emotional connections with the source material. In both cases, while the park premises are now part of this linked story, they have also become marketing venues since witnessing other guests playing the game may increase interest in trying the game.

Figure 6. Portal hidden behind the window dressing of a shop. Photograph by author, April 2016. [View larger image.]

[3.5] SotMK changes the park's landscape, but it does a similar thing with the concept of video games. While there are motion-sensing interfaces for more than one gaming system, and while there are virtual reality spaces that involve user motion and gestures, SotMK combines image recognition (spell cards held up to cameras) with the physicality of a real quest (walking from land to land, portal to portal). This makes the majority of the Magic Kingdom itself a gaming space, even a game itself. SotMK has some similarities to other quest and interactive games as they employ "traditional narrative techniques interspersed with interactivity" (Salter 2014, 6). Like other role-playing and trading card games, the individual cards have a character image, statistics, and descriptions: spell name, a rhyme describing the spell, spell type, attack type, card rarity, and the level number of each card's attack, boost, and shield properties. These cards level up when played correctly and lose power when played incorrectly; harder modes are about using the right combinations of spells to defeat particular enemies. SotMK reflects the elements of casual game design that Jesper Juul (2010) defines: a fiction, usability, interruptability, difficulty, and "juiciness" (30). The appeal of the fictional narrative has already been discussed; the game has user friendliness with its repetition and consistent design and outcomes; it has flexibility and interruptability, as users can stop after each portal or each villain; its difficulty is adjustable and more punishing on higher levels (but never impossible); and it has high levels of juiciness, or "excessive amounts of positive feedback" (Juul 2010, 45), when spells appear on-screen with colorful animations. As a result of these factors, SotMK can be deemed a casual game (though, as Juul argues, this is a debatable term, and some casual players may spend hours in the park playing) that has additional modes that can gratify more hardcore gamers. The game also has a satisfying dual goal. It has a virtual goal, that of defeating Hades to become a Master Sorcerer, preferably at the Gold level (figure 7), and there is also a physical goal, that of collecting all of the cards, a facet to the game that invites fan participation.

Figure 7. Portals revealing the Master Sorcerer medal and the sorcerer rank. Photograph by author, October 2014. [View larger image.]

[3.6] The most significant change that SotMK has wrought is its expansion of the concept of spatial stories in which the guest's role is privileged. Anastasia Salter (2014) describes spatial stories where "the player finds the story within his or her environment by taking on the role of 'you'" (27). While in this role, the visitor "soaks up the atmosphere of the world while following the rules of the experience" (Salter 2014, 27). Spatial stories provide a new level of immersion; Meyrav Koren-Kuik (2013) explains that narrative and spatial immersion are interwoven and an essential part of the "consumer/fandom model" now (150). In this case, the environment is the Magic Kingdom, usually familiar to the visitor but with new elements, sounds, and lighting effects that defamiliarize the space. Experiences like SotMK go beyond just more elaborate theming. Lead designer Ackley explains, "we're sort of changing the role of the guest to be the main character instead of somebody passing through the world" (quoted in Brigante 2012). Like Brett Martin (2004) notes (talking about the trading card game Magic: The Gathering [1993]), the player is a "central character of influence to the events that unfold in the realm of the imaginary" (140). The theme park and SotMK are not an "unbounded" fantasyscape as Magic is described as being (Martin 2004, 141); the theme park is a real place (with boundaries and controls) overlaid with the imaginary. Nevertheless, fans have taken on a greater role in the fantasy story and stand side by side with beloved characters. Parks, or at least certain attractions, are now being reimagined with this central guest role in mind.

4. Fan groups and practices

[4.1] SotMK has a large potential audience of at least a few thousand people per day despite its being a comparatively unknown attraction. Because of its easy mode with a low barrier to entry, the game caters to children and casual players, while the harder modes might attract adults and more experienced gamers. Ackley suggests that most guests will prefer the easy mode because of time constraints but that "locals and the hardcore gamers" will want more depth and length (quoted in Brigante 2012). The game works as a solo experience. However, because it is also in the theme park space, groups frequently play it. More practiced players and families might have multiple people holding up spell cards together so that the combinations are a team effort. In my couple of years playing the game (usually with my husband), I have witnessed diverse types of players: large families, couples, affinity groups, children, adults, men, women, solo fans, and off-duty cast members (Disney employees). The game could appeal to many fandoms: Disney film fans, Disney park fans, gamers, and card collectors/traders. The game does cater to repeat visitors (annual passholders, cast members) who may see community as an incentive to keep playing even once complete, but all types of guests participate daily.

[4.2] A fan culture has sprung up around the SotMK attraction. Ackley (quoted in Brigante 2012) was able to discern even during the test period that the game was "building a community of these traders and these sorcerers." Like with all fandoms, there are fans with a variety of styles, practices, and levels of intensity. Some SotMK fans care more about the gameplay aspect of the attraction while others prefer the collecting aspect; several engage in all facets. The common behavior that fans perform is playing the game. Some prefer to integrate it into their regular park visitation habits, playing a portal here and there between other attractions and activities. Others prefer playing the game and may not visit additional attractions. Every time an individual does play, she will interact with the portals in addition to with specific people: other players (met at the portals), nonplayers (inquiring about the portals), and cast members (met each time to collect a card packet). Trading cards is a recurrent activity, often happening at portals or in the Tortuga Tavern, a small restaurant that houses a portal and a meeting place for frequent players (figure 8). Collectors may bring card books, bags full of cards, or a stack of loose cards. When trading, I have been exposed to both the good and bad citizens of the game. In my first encounter with a young man who wanted to trade, he purposely exchanged a common card with me for a rare card before I was aware of the meaning of the symbols. He then did the same with another group of new sorcerers. His mother looked on and seemed pleased by his duplicitous behavior; no doubt, fandom is made of people, with "all their imperfections as well as their strengths" (Coppa 2014, 77). There might be an intimidation factor when encountering strangers that are already experienced in the game, especially if some might prey on a new player's lack of knowledge. The same behaviors occur with the much older park-based fandom of pin traders, for instance. Good citizens tend to outnumber the bad, however. It is not uncommon for fans to explain the game to new players, tell them the trading rules, give insider tips, trade appropriately, or even gift multiple cards. One of my first encounters with a Tortuga Tavern fan, in fact, yielded many trades that lent to completing at least a quarter of my collection. These kinds of daily practices illustrate the situatedness of park fandom but also the ways in which the culture is shifting, even influencing the interactions of other park visitors. There are groups of fans who play this game regularly, but it is hard to know yet whether they comprise a "subculture" within the Disney fan culture or a "community" with common values and spaces (Coppa 2014). Social media platforms contribute to fan "fragmentation," so there is some dispersal of members with like interests (Bennett 2014). The more accurate term here might be "affinity spaces" (Gee 2007, 87), as these tend to be self-organized, interactive spaces around a common passion (with the interest, not specific people or cultural markers, being what initially brings the group together). James Paul Gee (2007, 5) considers this type of "social affiliation" a powerful thing with the ability to generate "new ways for people to produce knowledge, participate in social interactions, and create learning," all things that SotMK players do. Regardless of what they are called, however, these groups have some clear rules.

Figure 8. Portal at Tortuga Tavern. Photograph by author, April 2016. [View larger image.]

[4.3] As noted, there are rules written into every aspect of the game that emphasize control or at least the authority commonly present in narratives and video games. It is heavily rules based, fitting in to the role-playing game model (though the game does not provide an opportunity to create or customize characters other than with spell choices). These rules govern the players, so their likelihood of deviance, at least within the story, is minimized. Fans present an additional layer of regulation. Major fans tend to use hero language and refer to themselves as sorcerers or Master Sorcerers; cast members around the park reinforce this language by calling players sorcerers or using phrases related to defending the Kingdom. The player "enacts" the magic role, associating it with wizards that "personify bravery and power" (Martin 2004, 141). SotMK does not allow for role-playing within the villain roles. Players defeat all of the villains to save the Magic Kingdom, and that alliance with good is unwavering. Fan practices are governed similarly. A market around rare or event-based cards has developed, with cards being sold on eBay or sold/traded within fan groups. As a result, a bad behavior that has arisen is selling or trading counterfeit cards. Since the images on self-printed cards are the same, the cards usually work in the game, so Disney has little ability to regulate this (nor do they try). Fans, however, have a tendency to self-police this kind of act. The public Facebook page of the Sorcerers of the Magic Kingdom Rebel Alliance fan group, for instance, warns that "Any reproduction or creation of fake cards will not be allowed for trade, selling or giving…Be honest in all manners regarding the authenticated cards." Like in many collector cultures, authentic artifacts are demanded. Also, the sorcerer role comes with embedded values; counterfeiting does not fit within that persona. This particular group has a Code of Ethics that defines the expected behaviors of the group members, provides a quick ethics test with a list of questions, and outlines the responsibilities to new sorcerers, each other, "our group," and "our game provider" (meaning Disney). The latter includes the line, when referring to respecting the decisions of Disney employees, that "Ultimately, Disney sets the rules to the game and we should follow these rules to be allowed to continue to play." This is only one group's rule set, but it does demonstrate the kinds of regulations that fans give themselves to guarantee the continued integrity of their practices, spaces, and objects of fandom.

[4.4] Sam Ford (2014) stresses that fan studies should go beyond fan fiction and more traditional modes of fan production. In this case, it is not only the written production of fans that is interesting but the ways in which they engage with the game itself and other in-park practices (really the "everyday process of fandom") that merit further study (Ford 2014, 65). The role-playing identity in this game is that of the Sorcerer, needed to save favorite Disney characters and the Kingdom itself. Amon (2014) explains (as related to cosplay) that it "offers participants the opportunity to construct their own identity through playful engagement with dogmatic text" (¶3.2). While playing within a theme park is certainly more restrictive than cosplay, it still allows for an alternative identity to the standard theme park guest. In this game, the sorcerer identity allows for playful engagement by way of spell casting. Its spell system is one of the creative aspects of the game. On medium mode, players need to determine the attack types that best fit the villain they are battling. On hard mode, this becomes randomized, so players must use the game graphics (which vary based on spell) to determine effective attacks and the spell's current power level. Winning includes multiple combination spells; getting the best combinations means constant trial and error. Some fans sort their card books based on favorite mixtures or encourage others to not ask players for combos but to try their own. Spell testing is one of the enjoyable elements for advanced and returning players. Though there is not the same freedom available with creating a deck in Magic: The Gathering (one of the pleasurable elements of that game according to Martin 2004) because the cards do not influence the story in the same way, battles are variable and the rules are only determined through experimentation. The designers planned this, as Ackley (quoted in Brigante 2012) asserts that "part of the game is intuiting what the rules are, because we're not announcing what the rules are—which spells work against which villain." They wanted the players to "discover them while playing. And no two experiences are exactly alike" (Brigante 2012). Despite the layers of control, the sorcerer is given affordances for creativity and identity construction. New sorcerers do actually learn as they play, increasing their specialized knowledge while in the park and then regularly sharing what they have learned online. Thus the player becomes a learner and a teacher, a combination in the spirit of Gee's aforementioned concept of affinity spaces.

[4.5] Like most fandoms in this age, there are public, online components connected with SotMK social groups. Lucy Bennett's (2014) four "areas of fandom and enquiry" (5) are defined as communication, creativity, knowledge, and organizational/civic power. While activism as such does not appear to have surfaced thus far in these groups (unless counting ethics within fan practices), the other three are the most common expressions of affinity for SotMK online. Communication to other fans manifests itself in groups on Facebook and other sites, generally associated with news, card updates, trading, and meeting opportunities. Creativity is illustrated by written and visual production efforts like wikis, blogs, photography, and mobile applications, of which there are at least three. There are at least three examples of SotMK fan fiction at FanFiction.net. Some fans invent new character cards, a form of theoretical modding, though not a literal one, as they are not playable within the game. Dozens of fan-made cards can be found on sites like Pinterest, Tumblr, and DeviantArt; they attempt to replicate the look of the cards but use other favorite Disney characters (or even non-Disney characters or fan fiction characters) with new spells (figure 9). Additional fan works include custom spell books, buttons, hair bows, or other crafts. Falling somewhere between creativity and knowledge would be the under-discussed practice in gaming of playthrough vids. For SotMK, these are both visual walkthroughs of the spaces and playthroughs; they are creative in that they are fan-produced videos but also demonstrate and provide knowledge to others. These are reproductions of the game without the materiality of the space, but they do give inquisitive nonplayers an encounter with the narrative. Much of the online production would fall under the knowledge category. As Bennett (2014) argues, "shared knowledge and its exchange is a central facet of fan culture" (9). The blogs, discussion forum threads on fan boards, card checklists, videos, and Wikia page all provide information to new sorcerers but also to veteran ones. The sharing of meaningful information might be enjoyable to fans, but it also contributes to the continuation of the practices in which they are invested. The conversations about SotMK online and within social media ensure the extension of the theme park space. Theme park fans have robust online cultures, so fans of this attraction are likewise served by existing sites of conversation (in addition to critiques, which are also present). A consideration of fan labor (production, conversation) reveals that fans impact the theme park space and the online discourse surrounding that space. They actively partake in the practices that shape the theme park and then interpret both the space and the practices.

Figure 9. SotMK fan-made card, created by the author and her husband. [View larger image.]

5. Transforming space

[5.1] With the interplay of these constituents (management, designers, fans), Magic Kingdom Park has been transformed into a convergence space (Jenkins 2006). The theme park is a canvas of exploration and a game while simultaneously facilitating a cultural shift. The stereotype of theme parks might be that visiting them is about experiencing as many attractions as possible. Decades of guidebooks and trip planning sites online are dedicated to maximizing time at the parks and hyperplanning to ensure as much. SotMK changes this perception; it slows down the pace of the visit and weaves not only a larger narrative together but represents a shift in the guest's role. Instead of being only a spectator, the visitor is a participant—a sorcerer. SotMK forces interactivity with the landscape; the user cannot choose to be passive. This distinction means that whether a player identifies as a fan (and/or prefers a sorcerer identity) or not, she is not really merely a "follower" because of the active engagement necessary to play at all (Coppa 2014, 75). SotMK changes the patterns and identities of guests who partake in the experience. Most guests still hold to the traditional model of visitation, but some fans embrace this alternate mode of engaging with the object of fandom. The very "process of convergence," according to Koren-Kuik (2013), allows for the establishing of identity, personal narratives, individuality, and self-positioning within the space (152). In this way, the new conception of interactive attractions helps to strengthen the fandom model and allows for new ways to explore that role. However, because of the game's location in the commercial space, Disney has the ultimate control over the attraction. They could remove it tomorrow or allow it to stagnate. They have not released nonevent cards in years, for instance, which could eventually result in a reduction of interest from frequent players. Nonetheless, the model of park visitation has already been altered by the attraction and those like it. Creators sparked the change, but fans cocreated it, accepted it, and are the ones who play each day. Many postmodern and cultural critics have associated theme parks with the notion of consumption. Janet Wasko (2001), for instance, discusses Disney products (whether a film or the concept of fantasy), values, ideologies, and spaces in terms of the "process of consumption" (185). Sharp critiques include that of Umberto Eco ([1986] 1990), who describes Disneyland as "a place of total passivity" where visitors "must agree to behave as robots" (48). The visitors in this description are dronelike, both consuming and uncritical. SotMK would still be classed as part of the whole park, which generates profit for a large corporation, but the notion of "consumption" has shifted to that of the "experience economy" (Pine and Gilmore 1999). It is not only goods, products, or services that matter but also experiences and, in some cases, transformations. Fans will consume the space, the experience, and the culture in addition to merchandise, but this is active, selective consumption (figure 10). Fans go beyond passivity when they participate in processes of interpretation and production. In fact, Martin (2004) argues that imagination itself, including the "fantastic imaginary" that manifests itself in games like SotMK or Magic: The Gathering, is an activity that consumers "generate…during consumption" (136). Directly related to the theme park would be the guest disposition that desires an "active participation in the fantastic imaginary setting" (Martin 2004, 143), not mere passive consumption. With fandom, there is an essence of ownership but not always allowances for such within corporate spaces (though, as illustrated, the fan role continues to expand). Even so, agency may be observed in fan practices, and there has been a shift from the "fan within a space" to the "process of making that space" (Parrish 2013, ¶4.8).

Figure 10. Tangible SotMK items: cards in a collector's album, the paper game, and pins. Photograph by author, April 2016. [View larger image.]

[5.2] Fans rarely possess equal power with commercial producers. Despite this, SotMK fans co-opt the space, reconstructing the expected practices of theme park visitors. In fact, while the text of SotMK cannot be changed by fans, the text of the Magic Kingdom is being actively altered. In this way, fans are participating in a process, similar to what Juli Parrish (2013) describes (in reference to fan fiction) as "world building," or a "process that remakes the place itself" rather than just borrowing pieces of it (¶0.1). The Magic Kingdom is a physical place and thus a different kind of text, but it is dynamically influenced by the guests who traverse its paths. Some of the behaviors associated with home or typically coded as private have entered the public space of the theme park. SotMK represents some of these: video gaming, individual card collecting, loose-knit communities, family play, social media interaction, quests, role-playing, and creative spell casting. Behaviors such as spending hours playing a video game and hanging out at the theme park without partaking in the big attractions might be pathologized. Despite the large number and diversity of Disney fans, they may be marginalized as strange or their behaviors construed as living at the theme park. Wasko (2001), for instance, describes Disneyphiles or "Disney freaks" and the fans that are disparaged for their lifestyle, expended income, values, or apparently blind acceptance of Disney's "encoded messages" (204). It may be assumed that fans here are enmeshed in "escapism from the real world," as one player of Magic: The Gathering mentions as his reason for participation (Martin 2004, 140). Nonetheless, this is complicated by the many players who don't cite this reason and by Juul's (2010) observations about the stereotypes of hardcore gamers where "children, jobs, and general adult responsibilities" interfere with gaming (51). The majority of people, he illustrates, are flexible and move between intensity of play during life stages. SotMK players represent some ways in which fans can operate against the status quo in the park and in the perceptions of their interests (annual passholders tend to have day jobs, after all). There is little doubt that fan practices are sanctioned by Disney at least theoretically. Koren-Kuik (2013), in fact, argues that "Disney encourages participatory fandom in its most complex and wide range form, inviting fans not only to watch movies and television shows but also play, sing, learn, and experience" (147). The theme parks, are, according to Koren-Kuik, the "jewels in the crown of this participatory fandom construct" (147). Long existing as places to play and experience, theme parks now position fans as characters in their favorite narratives. Their voices are also sought out in interpretive exercises. These voices are not suppressed because fans are a part of the capitalist system and a "centerpiece…of marketing strategies"; they assist brand recognition and loyalty and now operate with increased "cultural currency" (Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 2007, 4, 8). Fans are allowed to repurpose spaces, and perhaps the smaller scope of SotMK has meant less regulation. Pin trading and collectible activities are generally more controlled. The norm of fan collecting is continued with the cards, however, and certainly the assumption of fan loyalty predates the change to more interactive media offerings.

[5.3] The SotMK experience was easier to prepare because of a preexisting fan presence. In addition to the brand representation encouraged by Disney with many guests wearing Mickey Mouse ears, Disney shirts, and pin lanyards, there were already common visitation rituals, organically-developed watering holes, and location-based fannish culture. For example, though adult costumes are not allowed at Disney parks except during a few special events, other forms of fan identification through dress have arisen: wearing Disney-produced or fan-produced geek shirts, clothes or items identifying Disney-focused social clubs or online affinity groups, pin vests or display books indicating pin traders or collectors, coordinated dress practices on designated days (e.g., Bats Day, a Gothic tradition at Disneyland; Dapper Day, a fancy dress event at more than one park; and Gay Day, a celebration with political undertones at multiple parks), and Disneybounding, a Tumblr-driven practice wherein park visitors assemble outfits that represent the colors, styles, and patterns of Disney characters. The latter is a fashion statement, an expression of fandom, and an online practice (with the post illustrating the chosen attire as popular as is wearing the clothes in the park). These practices signify the public performance of fandom. Like SotMK, they are also part of the ongoing interplay between park constituents. Constituent interactions represent the larger relationships between fans and producers including the fuzzy line between the two (i.e., fans as producers, producers as fans) and the benefits found in mutual goals. In the case of SotMK, both fans and Disney gain from participation and shape each other in the process. Recalling the text of the SotMK Rebel Alliance group, however, the fans do play at the whim of Disney, so a hierarchy is maintained. Fan activities are encouraged, as Jonathan Gray, Cornel Sandvoss, and C. Lee Harrington (2007) affirm, "as long as their activities do not divert from principles of capitalist exchange and recognize industries' legal ownership of the object of fandom" (4). This is accepted within SotMK groups, but their reliance on Disney is greater than is the case with other objects of fandom because the game cannot be transported or modified as a book or film can. The place-based nature of SotMK guarantees that the fan practices are likely to be different. At least the aspect of card collecting is portable, giving the fans a tangible element that can leave the park. The home game, on the other hand, bears only passing resemblance to its in-park version; multiple boards need to be bought for completion, and it is more about learning appropriate spells for villains than experiencing a physical quest.

[5.4] Part of fan participation culture is undergoing fannish processes of "constant discussion, criticism, and theorization" (Ford 2014, 63). Like with other fandoms, Disney theme park fandom is a balance of "fascination and frustration" (Jenkins 2006, 258), and affinity spaces facilitate both. Despite the fun or interesting features of games like SotMK, fans have expressed a number of concerns about interactive gaming additions. Looking at the comments section in news releases about interactive games or through discussion forum responses on popular fan sites reveals some common anxieties. These can be characterized as follows: fans who question Disney's choices in adding nonsubstantial attractions over more elaborate ones; fans who do not appear to be the target audience of interactive games; fans who dislike technological enhancements or believe that technologies are better in home activities; and fans who worry about the future of theme park experiences, preferring more passive attractions or experiences with all physical/practical sets. The first anxiety reflects a common critique from Disney fans, that of how the corporation spends their capital. In the case of the Magic Kingdom, a park with near-constant crowds, Disney found that multiple interactive additions were viable expenditures to relieve crowding pressures and provide more options for guests. The next category would be fans who do not appreciate attractions that are not personally appealing to them, a display of human nature. Ackley (quoted in Brigante 2012) states that SotMK is purposely "serving what previously has been an unserved constituency." He might mean younger generations who are used to a technology-mediated world, video games, interactivity, and in some cases, card collecting and role-playing games. Plenty of players do not fit this description, but some of the defense of the game online came from younger players and especially from parents, many of whom argued that their children found interactive games more appealing than traditional rides and shows.

[5.5] The last statement could be precisely what is driving the worries of the fans that prefer the theme park experiences they are used to, as some core aesthetic values are at stake. These criticisms can be broadly applied to the shifting focus toward interactivity within theme parks as a whole and may not be directed at specific experiences like SotMK. Dark rides with cinematic features like elaborate sets, lighting techniques, music, and animatronic figures are also my favorite kinds of experiences, but attraction variety is a boon for a growing industry. Also, theme parks have had role-playing (e.g., Sorcerer's Workshop at Disney California Adventure) and interactive experiences (e.g., ImageWorks at Epcot) in the past; they just looked different and had a less obvious technological interface. There is apprehension about the use of technology in parks, but it appears to be a losing battle. While there are fans and industry professionals who worry about the extent of technological incursion (i.e., virtual reality-type immersion displacing physical immersive environments), attractions are becoming only more technological. As more than one article attests to (Brigante 2012; Martens 2016), parks are opting for a balance between physical and virtual experiences both in the park and even within attractions. Advanced technology may enhance or detract from theme park attractions, but it will continue to be used. The history of the amusement industry is built on technology, and themed entertainment venues have continued to leverage it. This article addressed SotMK's employment of practices that are typically done at home, but this is also changing with the widespread use of mobile devices (more home/private activities have become portable—communication, reading, learning, gaming, etc.). The concerns of Disney park fans should demonstrate that whether playing games like SotMK or not, they remain invested in the theme park space and its future disposition.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] With the decision to introduce more interactive elements into their theme parks including fully-realized, participatory quests, Disney management and creative personnel encouraged the transformation of the theme park into a space for more detailed exploration. Fans took this up, with the game contributing to new practices and levels of engagement. Fan culture cemented the notion of participation in parks, and their involvement will continue to shape theme park spaces.

Some past perceptions of theme parks include that they are spectacles where guests passively view wonders. Now, theme parks have become sites for some of the concepts of our time: hypermediated play and participatory culture. Judging by these examples and the ones emerging at other parks, companies will persist in adding layers of experience to existing spaces. Significantly, the position or role of guests and fans at parks has changed. They are not only passive spectators but also the marketers, interpreters, culture creators, heroines, heroes, and sorcerers of the Disney theme park. Dedicated fans may respond by partaking in these offerings or by expressing further anxiety, but they will likely continue to participate in the complex negotiation between producers and consumers. Affinity spaces, whether they are online forums dedicated to Disney parks or the locations at the parks themselves, are fascinating sites of cultural production that should continue to be studied. Likewise, examining the everyday practices of fans within commercial confines can lead to insight about the ways in which they contribute to the objects or spaces of fandom.