1. Introduction

[1.1] As an academic doing cultural studies, I feel a particular comfort in writing about subaltern and oppressed populations. Deconstructing the ways in which groups of people are silenced and oppressed is vital work, for one, which is still too often marginalized or dismissed. So too is documenting the existence of cultural logics and practices that act as alternatives to the mainstream. Writing as a member of one of these groups is hazardous. Academia is never as progressive as we hope, and it is easy to be identified with one's work in reductive ways. At the same time, it is powerful. Scholars today have the benefit of generations of brave earlier academics who wrote from their own vantage points and proved the importance of embodied experience in research. Female scholars are still instrumental in women's and feminist studies; queer academics in sexuality studies; African American academics in African American and postcolonial fields; this list could go on. Acafans created the contemporary field of fan studies by writing from their unique perspectives and by refusing shame and stigma.

[1.2] But doing scholarly work solely as a critique of normative ideologies and institutions from the perspective of stigmatized groups also produces unique blind spots that academia (and fan studies in particular) is overdue to address. Some of this work is being done via theories of intersectionality: being both African American and female or lesbian and a fan makes culture work differently than when only one of the above is true. But by focusing our attention on people suffering under increasing vectors of marginalization, we risk scholarship becoming only the study of oppression.

[1.3] Scholarship must also analyze the workings of power and of groups with degrees of privilege. Without transforming the ways in which privileged identities work, identifying new ways of doing whiteness, masculinity, heterosexuality, we are left with simply (though importantly!) empowering groups in societies still stacked against them.

[1.4] To these ends, in this article I analyze the workings of masculinity, a privileged identity, within fandom, an oft-stigmatized subcultural group. I define masculinity as a gendered identity, a way of acting and relating to others, which is often socially and implicitly defined as the inverse of femininity. Masculinity is not, however, confined to male subjects or male bodies. For instance, a butch woman has a masculine gender identity but performs it with a body sexed as female (note 1). Multiple types of masculinities exist, and, just as masculinity is privileged over femininity in patriarchal societies, some masculinities are privileged and positioned above others (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005, 846). From this emerges the concept of hegemonic masculinity, a normative ideal that "embodies the currently most honored way of being a man, requires all other men to position themselves in relation to it, and ideologically legitimates the global subordination of women to men" (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005, 832).

[1.5] I ground this analysis in American otaku fandom during the first decade of the 2000s. I chose this case study because it is a world I knew well and in which I am implicated. As a teenaged white lesbian fan who fell hard for Sailor Moon (1995–2000) after an accidental Cartoon Network viewing on a family vacation in the late 1990s, American otakudom of this time is where I wrote and read my first slash, or yaoi, fiction, watched untold numbers of anime music videos (AMVs), reclaimed childhood sewing skills for use in cosplay, and met a great number of good friends. I do not claim here to speak for fandom or even for otakudom. Rather, I use autoethnographic techniques to critically reflect on my own experiences as a fan and a young woman with a more feminine gender identity.

[1.6] There is a strong tradition of reflecting on personal fannish experiences in acafannish writing, for example Zubernis and Larsen 2012 and 2013, Penley 1991, Okabe 2012b, Jenkins 1992 and his ongoing Confessions of an Aca-Fan blog. This resonates with autoethnographic methodology, wherein anthropologists "direct the ethnographic lens onto themselves…writing autobiographical life and oral histories, reflexive accounts of personal experience" (O'Reilly 2012, 130). For more introduction to autoethnographic methods, see Ellis, Adams, and Bochner (2011). I follow Krane (2009) and Kipnis (1992) in combining my autoethnographic reflection with a feminist and queer analytical lens. Keeping my own positionality in view is particularly crucial to this analysis because gender is fundamentally relational. Masculine identities and practices of masculinity "are also affected by new configurations of women's identity and practice, especially among younger women—which are increasingly acknowledged by younger men" (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005, 848).

[1.7] I argue that although American otakudom was and is a subcultural space, it is still structured by hegemonic masculinity that demands overt heterosexuality and a controlling presence, particularly over women. However, it is also a space where the cracks in that hegemony open wider than in mainstream environments, such as schools. I apply queer theorist Edelman's (2004) concepts of jouissance and futurism as well as theory from masculinity studies, primarily Pascoe (2007), to interrogate the dynamics of and practices associated with both normative and nonnormative masculinities in this case. At this time, when the field of fan studies is starting to become institutionalized and fan practices are moving more and more into the cultural mainstream, the transgressive practices and spaces must be maintained. As fans and academics, we must also continue to interrogate and critique the ways in which our practices sometimes reinforce damaging cultural structures.

2. Welcome to Oz(aka)

[2.1] Masculinity plays out and is played upon in the spaces of interaction between individual fans, their creations, their audiences, fannish cultures, and the wider society from which fans come to fandom. I analyze American otakudom as an ecology, which "encourages us to pay attention to both the individual and social aspects of authorship and, perhaps more importantly, to the interactions between them" (Turk and Johnson 2012, ¶5.1). Getting at these spaces and interactions requires a basic grasp of American otakudom during the turn of the millennium.

[2.2] Anime fandom has been around in the United States for decades, at the least since the 1970s. In the earlier years, college anime clubs and screening rooms at conventions provided the most reliable access to programs that were not widely shown in the US. The MIT Anime Club, for example, hosted weekly screenings of anime in its original Japanese form (in my experience, known as raw anime) wherein "someone would stand up at the beginning and tell the plot, often drawing on what they remembered when they heard someone else recite the plot at another screening" (Jenkins 2006, 162). Survey and interview research of anime clubs in 1998–1999 found them to be 76–85 percent male, a strong contrast to the many female-dominated Western media fandoms (Napier 2000, 247). In the late 1980s and 1990s, anime increasingly became available through fansubbing, "the amateur translation and subtitling of Japanese anime," and a network of fans who mailed VHS tapes back and forth (Jenkins 2006, 162). Fans used these same technologies of analog VHS systems, eventually replaced with digital editing tools, to create their own AMVs by sampling clips of anime and then editing them together to music of their choice (Ito 2012a; Close 2014). Even as anime conventions began to proliferate, the pool of AMV creators remained small to the extent that EK, an AMV editor who began creating videos in the late 1990s, told researcher Mimi Ito that in 1998–1999, "pretty much every AMV editor in the US knew each other, or knew of each other" (Ito 2012a, 281).

[2.3] Mainstream, particularly university, Internet accessibility in the 2000s dramatically changed American otakudom's dynamics. Anime could now be downloaded via BitTorrent, and fansubbing groups produced speedy and high-quality subtitled versions of anime soon after it aired in Japan. These fan subs were shared with the rest of otakudom for free via library-style Web sites of BitTorrent links. The growing accessibility of computers and the Internet also vastly expanded American otakudom's internal production. Fans created and shared fan fiction, fan art, show reviews, industry news, cosplay tutorials, con photos, and many, many message board discussion threads. Particularly notable was the founding of Anime Music Videos (http://www.animemusicvideos.org/), a site that became an important hub of otakudom through comprehensively indexing and hosting AMVs, in 2000, 5 years in advance of the advent of mainstream video-sharing sites such as YouTube (Ito 2012a, 281).

[2.4] Particularly after the gigantic success of the Pokémon franchise, fan demographics became "younger and included more female fans" (Eng 2012, 165). Users of Anime Music Videos who responded to a research survey posted on the site's home page in 2006, for instance, were 62 percent male and 38 percent female (Ito 2012a, 282). This is a 10–20 percent shift from Napier's findings in the late 1990s. AMV editor Zettai estimated the true demographics of AMV editors during that time as more even still, as he noted that when "you would go to Anime Music Videos and look at the most used anime [in AMVs hosted on the site], you would see Inuyasha and Yu Yu Hakusho," shows with a large female viewership (quoted in Close 2014). When I started as a college freshman in 2003, the anime club booth at the extracurricular fair was staffed exclusively by guys. By the time of my senior year in 2007, our anime club officers, save one, were all female.

[2.5] Otakudom's place in wider American culture also changed during 2000–2009. These years witnessed anime and manga's emergence into the mainstream, as they appeared on television screens, in DVD stores, and on the shelves of chain retailers such as Barnes and Noble. They likewise found their way into the spaces of the broader American geek subculture, popping up on the convention floors and panels of the San Diego Comic-Con and New York Comic Con. The growing visibility of Japanese popular culture inspired anxiety and some hostility from both mainstream and subcultural America. Comedy Central show South Park (1997–), for example, parodied American kids' Pokémon fandom by portraying the franchise as an attempt by Japan to brainwash and control American kids. The Comic Journal's Dirk Deppey recalls standing outside Emerald CityCon in 2005 and seeing a young girl in a kimono, distressed that there had been very little manga on display, leaving the convention with her family. Intrigued, Deppey related the story to a friend "prominent in the art-comics publishing scene. 'I hate to say it, but good,' was his reply," as was that of several other "indy-comics and superhero-comics professionals" whom Deppey talked to that day (Deppey 2005, 15). His article "She's Got Her Own Thing Now" spared few words in expressing his disgust at the American comics industry's failure to consider or value female readers. Deppey's description of manga as a "women's thing" is odd in light of the otaku demographics noted earlier, but it demonstrates the associations that some in the established American comics scene had of otaku.

[2.6] These changing dynamics contributed to otakudom's vitality but also produced anxiety over the shifting culture. Much of this anxiety was highly gendered. Mainstream acceptance of Japanese popular culture, particularly Pokémon, stemmed from a sense that it was soft, innocent, and cute—read feminine—especially when parents compared the content to first-person shooter video games or American action films (Allison 2006, 250–53). This frustrated many otaku, who went to great lengths to acquire raw or fan-subbed copies of even those series broadcast on American television, as "violence, nudity, and sexuality are all much more censored by US TV than is the case in Japan" (Allison 2006, 292). American otaku created the Sailor Moon Uncensored Web site, for example, to track each and every change made to the American broadcast of famed shojo series Sailor Moon—ironic as the Sailor Moon broadcast was heavily critiqued by Japanese and American television executives for hewing too closely to the Japanese original and thus alienating American girls (Allison 2006, 152). Similarly, AMV editor Inertia described his hugely popular AMV Sail On as an advertisement for and introduction to his beloved series One Piece, "an epic series, long running and always fresh, but it hasn't got the best recognition this side of the pond…Do note this is from the original One Piece, not the hacked up American dub version with water pistols, cork guns and no blood or plot" (quoted in Ito 2012a, 283–84).

[2.7] This popular (mis)perception of anime and manga as feminine and child-safe media changed how nonfans perceived my teenaged otakudom—and it grated. I vividly recall my father sitting down to watch a tense, emotional episode of science-fiction political drama Gundam Wing with me and getting up after a few minutes, shaking his head at his inability to follow "these new kids' shows." For me, even as a female fan, instances like these were inflected as masculinity challenges. A masculinity challenge is a "contextual interaction that resulted in masculine degradation" and labels the challenged individual as subordinate and lacking in masculinity (Messerschmidt 2000, 298). In that instance, my father, a common source for children's definitions of masculinity, dismissed my fannish engagement as childish and emotional rather than adult and logical—that is, masculine.

[2.8] The turn of the millennium was an exciting and exasperating time to be an American otaku. Our fannish objects and texts were emerging into greater prominence but often in ways that were out of our control and even threatening. Otakudom was expanding, bringing in people like me who needed the "hacked up American dub" versions to introduce us to anime in the first place. This also brought the different conceptions of fandom into conflict with each other. The fans who maintained the Sailor Moon Uncensored Web site kept a running critique of other fans, the Save Our Sailors (SOS) campaign, who lobbied to keep dubbed versions of anime on American television. During my tenure as copresident of my college anime club, a past president contacted the club. He and another club alumnus were returning to campus to finish painting an anime-inspired mural. He hoped that one of the club's officers could host them in the dorms. My "otaku ethic," where Okabe (2012b) emphasizes the importance of maintaining and extending networks of fans, crashed against a very gendered concern about having a man whom I did not know personally stay in my room. When a friend who had known the former president told me he was the sort of otaku who "didn't think you were a real fan unless you were watching raw anime on an old VHS tape," the antithesis of my fandom, my mind was made up. We recommended the visitors stay in a hotel—not a decision that I recall with pride.

3. "There is life outside your apartment"

[3.1] Fans, even if they are white, straight, and male, are far from the top of the cultural hierarchy. Jenkins points out the way in which William Shatner's (in)famous 1986 sketch on Saturday Night Live congealed multiple stereotypes of fans. Among other points, fans are denigrated as "social misfits who have become so obsessed with the show that it forecloses other types of social experience…are feminized and/or desexualized through their intimate engagement with mass culture…[and] are infantile, emotionally and intellectually immature" (Jenkins 1992, 10). Shatner's skit marks both active heterosexuality and engagement with media only through genres such as sports and news as key requirements of normative masculinity. As almost all of the fans in the skit are depicted by white male comic actors, these stereotypes are also ways in which Trekkers are "doing whiteness incorrectly" (Stanfill 2011, ¶2.10). Media often depicts such white male fans as recuperable; so-called happy endings occur when fans make the choice to give up their fannish behaviors and get married, thereby achieving normative masculinity.

[3.2] These references and stereotypes might feel dated in the current Internet-enabled Age of the Geek. Fanboy auteurs like J. J. Abrams or Joss Whedon are visible and successful, and media corporations increasingly recognize fans' monetary power and sometimes also their intellectual and creative abilities. Otakudom is a prime example of these dynamics. Many American anime distribution companies were founded by former otaku, or they hired from the ranks of talented (and self-taught) subtitling groups (Jenkins 2006, 163). Ito and Okabe pinpoint an otaku ethic, "guidelines that dictate how fans should 'give back to the industry' and what content is appropriate for subbing and distribution" (Ito 2012b, 180; Okabe 2012b). Many BitTorrent library sites would remove torrent files for any show that had been licensed for distribution in the United States, and I was one of many fans who refused to watch the fan sub of a licensed show even if it was available online. This was not out of fear of cease and desist letters or other industry actions but out of a feeling of shared mission: we all had to support anime if it was going to succeed in the face of the domestic American entertainment industry.

[3.3] Unfortunately, fan stereotypes are not so simply dismissed. The now almost 30-year-old Shatner skit still serves as an industry reference point. Fred Lehne, a guest actor on Supernatural 2005), a US TV show with a very active fan community, told researchers that "Everyone saw William Shatner on Saturday Night Live say 'Get a life' to fans, and I think he's kind of an asshole for saying that. Kind of a slap in the face to your fans" (quoted in Zubernis and Larsen 2012, 212). Even as Lehne and much of Supernatural's creative team disavow negative fan stereotypes, those stereotypes remain to structure the discourse.

[3.4] That discourse is also structured by the evolution of hegemonic masculinity from the time of Shatner's skit and Jenkins's writing in 1992. Fanboy auteurs with mainstream success, such as Abrams or Tarantino, are a particular kind of fan: one who channels fannish engagement into the creation of so-called original work that can be sold in the commercial marketplace. As Jenkins noted in 2006, fan parodies or "'calling card' movies to try to break into the film industry" were contested but generally enjoyed much broader legal protection and corporate support than did more clearly appropriative work like fan fiction or fan vids (Jenkins 2006, 158). This definition of hegemonic masculinity admits fans but hinges on their production of (albeit textual) offspring and thus at a broad level on heterosexual reproduction.

[3.5] Even given the fanboy auteur example of a normative fannish masculinity, shame about being a fan and engaging in fannish activities is present—and contested—within fandom itself. It might surprise nonfans that editor dokidoki's video "Stop Watching Anime and Go Outside!" won multiple Viewer's Choice awards in the Anime Music Videos 2007 contest (video 1) (note 2).

Video 1. dokidoki, "Stop Watching Anime and Go Outside!" (2007).

[3.6] The video uses clips from 35 different anime along with the Avenue Q song "There is Life Outside Your Apartment." It stages a fan's friends drawing him outside his apartment to discover life, defined in the video as heterosexual intercourse and the physical place of Japan itself, and then cheering his return to the apartment to have sex with a cat-cosplaying moe-style Japanese girl he met outside a furry convention. The narrative ends, however, with the girl's discovery of the fan's obsession with otaku culture and (although improbable) evidence that he has been stalking her. She runs from the male fan, now outed as a creep. The fan's initial contact with the girl seemed to fulfill hegemonic masculine criteria—meeting a female in public and convincing her to initiate a relationship. By contrast, surreptitiously stalking the girl by technological means created an artificial and sexually violent situation where the male fan was "in masculine control and in which they could not be rejected by 'emasculating' boys and girls no matter how their bodies appeared or acted" (Messerschmidt 2000, 302). Messerschmidt documents such strategies as (criminally culpable) ways in which men with subordinate masculinities try to validate themselves as real men. Accordingly, in the last shot of the narrative, the fan is suggested to have been homosexual all along, in love with the friend who brought him out of the apartment.

[3.7] Many of the awards for "Stop Watching Anime and Go Outside!" are for humor. It's best understood as a fannish self-parody, as suggested in editor dokidoki's annotation "Your room doesn't look like this…does it?" on shots of the apartment stuffed full of otaku merchandise and pictures as well as stalking paraphernalia. The editor also includes a final credits screen after the narrative conclusion with the text, "Now that I've finished making this video, I should go outside…" followed a few seconds later by "Nah, I like it in here." Versions that screened at conventions ended instead with a specialized note: "Well, you're at a convention…That's a start…sort of…" In this self-parody, the editor calls up the specter of male fan stereotypes but ultimately validates fan practices. He dramatizes his choice to remain in otakudom (that is, watching anime) and more subtly asserts his own cultural expertise via visual jokes and notes requiring sophisticated knowledge of both high cultural references, such as the critically acclaimed Avenue Q, and the Japanese language. The video is tightly edited and required advanced postproduction skills to create the multiple visual puns and unlikely lyrical matches, implicitly making the case for dokidoki as a fanboy auteur.

[3.8] Unlike William Shatner, dokidoki is not seriously suggesting that anyone leave otakudom. "Stop Watching Anime and Go Outside!" is, however, also drawing clear boundaries about who does otaku right and who does it wrong. Good otaku learn about Japan, are not quite as obsessive as the fan in the video, and, in particular, are in control of their masculinity. Fannish anxieties emerge especially strongly when nonfan judgments or spaces are invoked. Zubernis and Larsen heard female real-person slash "fans worry about actors finding racy fanfiction, or just squeeful posts about Dean Winchester's rare appearances in a tee shirt" (2012, 213). Editor dokidoki stages anxiety about how a woman would respond to male otakudom, even if the woman in question is a fan herself, by suddenly transforming a scene of acceptable behavior by a man meeting a woman into the final step in a criminal stalking campaign. Fannish practices pushing at the boundaries of normative values, like explicit fan fiction that demonstrates an active and agentic female sexuality or moe fandom that invokes the specter of pedophilia through the fetishization of young characters, are particularly likely to be censured by other fans who worry that those fans make the whole community look bad. For more discussion of moe fandom, readers could begin with its entry at Fanlore (http://fanlore.org/wiki/Moe) and Patrick Galbraith's 2014 The Moe Manifesto.

4. Fandom as Sinthomosexuality

[4.1] Acafans, including myself, often feel the pressure of the outside view almost by definition. We continually translate fan practices to the historically skeptical outside audience of academia. One very effective strategy to validate fans and their practices has been to attach them to existing cultural discourses of legitimation. The word transformative in Organization for Transformative Works, for example, references the US Supreme Court's definition of fair use. This work is vital in practical advocacy and created the space within academia where scholars can celebrate, debate, and critique issues in fan studies.

[4.2] This strategy becomes problematic, however, when it leads to the impression that only those fans and fan practices which fit best with existing legitimating discourses are valued (Close 2014, 209). As fans, acafans are well positioned to notice this gap. In a conversation with other acafans on Henry Jenkins's blog, Kristina Busse writes that "if another scholar gets to read one story, sees one vid, I want it to conform to traditional aesthetic notions…When we choose fan works that fit into our arguments, that make fandom look more creative, more political, more subversive to outsiders because that's the image we want to give to the world at large, are we ultimately misrepresenting and betraying fandom?"(quoted in Jenkins 2011). Monden argues that such has been the case in scholarship on shojo manga, whereby researchers overemphasize boys' love and gender-bending genres and evince "a lack of scholarly interest in 'typical' or 'conventional' shoujo manga," which portray a more girlish femininity (Monden 2010).

[4.3] The irony of a progressive, politically engaged feminist scholarship neglecting and even devaluing femininity indicates why it is not enough for transgressive subcultures to be legitimized and absorbed into the mainstream. Edelman (2004, 19) takes issue with the normalizing and legitimizing goals of much mainstream gay activism, such as marriage legalization and securing the right for openly gay people to serve in the military. He argues that even if actual homosexual people gain these rights and become full citizens in the larger culture, the rhetorical, theoretical place currently occupied by homosexuality (particularly gay male cruising culture) will still exist. That place, which he calls sinthomosexuality, will simply be occupied by a different group or by those who continue practices, such as cruising, that are contrary to broader mainstream values (Edelman 2004, 38–41). The overall societal power structure widens to include homosexuals as another privileged group, but the preexisting workings of power remain largely intact. Similarly, I argue that we cannot accept a mainstream redefinition of fandom to only what resembles academic argument or industry-sanctioned interactivity.

[4.4] The cultural figure of sinthomosexuality is more specific than simply a common enemy around which the larger culture rallies itself. Sinthomosexuality centers jouissance, "stupid enjoyment" or continuously circling and repeating pleasure without defined meaning (Edelman 2004, 38). Normative society, structured by its legitimizing discourses, shuns jouissance. It defines itself against jouissance's (immediate, repetitive, meaningless) pleasures and instead dedicates itself to the promise of perfect pleasure in the future—aging, maturing, progressing, improving, increasing to a perfect state. As long as homosexuality is associated with "just sex," rather than the responsible (re)production of the future in the form of children, it occupies the place of sinthomosexuality (Edelman 2004, 40).

[4.5] Devotion to meaningless pleasure, stupid enjoyment, refusing responsible heterosexual reproduction—there is remarkable overlap between Edelman's definition of sinthomosexuality and stereotypes of fan culture. Just as hooking up is central to many sexual subcultures, rewatching, reworking, reviewing, and redoing are central aspects of many fannish practices. For instance, the categories coded into Anime Music Videos for viewer feedback on AMV's include rewatch value alongside more traditional criteria like originality or technical proficiency. This queer, fannish emphasis on the re, rather than the mix, is the place where creation and authorship in fan communities most clearly opposes normative practices of future-oriented production.

[4.6] As Edelman urges holding onto jouissance, the practices that are the most transgressive, oppositional, and powerful if also some of the most potentially problematic, I focus on two prominent instances of texts and practices created within otakudom that emphasize the re rather than the mix: the AMV Hell video phenomenon and the male crossplay of Sailor Bubba and Man Faye. All of these fan texts were prominent within American otakudom during the first decade of the millennium and, particularly because of their transgressive nature, created friction during this period when the fandom was already struggling with increased membership and cultural visibility.

5. AMV Hell and masculine confirmation rituals

[5.1] Editors Zarxrax and SSGWNBTD (SSG) made their first AMV Hell video in 2004. AMV Hell videos are compilations, each featuring a series of short clips paired with different songs. The idea spawned from AIM conversations where the two editors played with matching audio and video (note 3). As SSG describes it, this aesthetic appealed to him on the basis of his appreciation for variety-style comedy shows and because "editing to a full song was difficult. Most of the time there just wasn't enough action in the source anime to make a 4-minute music video interesting…By 2003, I had maybe 20 or 30 short clips, most terrible." Zarxrax eventually suggested that they put some of the clips together into one AMV and submit it to the contests at a few conventions. Each video and the series as a whole aims to be comedic, with a style aptly described by the tagline at the end of the first AMV Hell: "Now, nothing is sacred."

[5.2] To say AMV Hell caught on in American otakudom would be an understatement. "AMV Hell 1," their first video, won numerous awards at conventions as well as Anime Music Videos Viewer's Choice awards for Best Comedy and Most Original Video (video 2). To Zarxrax and SSG's great surprise, AMV Hell grew into a series of multieditor project videos that they organized as well as AMV Championship Edition weekly editing events and the AMV Minis project, whereby new segments of AMV Hell are produced in smaller chunks to help Zarxrax manage the ongoing production. Some of the later AMV Hell videos are of motion-picture length: "Anime Hell 3" (2005), the first multieditor project, contained 232 separate segments. A full 10 years after the debut of the original videos, AMV Hell continues with an active dedicated Web site (note 4). This longevity is an even more remarkable feat considering the changes in otakudom between 2003 and 2013, as discussed earlier, as well as Zarxrax and SSG's impressive dedication to the project throughout a full decade of their lives.

Video 2. "AMV Hell 1" (September 23, 2006).

[5.3] AMV Hell's aesthetic is antinarrative, pulling from the principles of jouissance in its continual repetition of short segments that each have a joke (note 5). Many of these jokes highlight the sexuality in the anime shown, and the series as a whole revels in sexual imagery. Male fans are continually stereotyped in mainstream American culture as sexually inexperienced. As an active and overt heterosexuality is a key component to developing a hegemonic masculine identity, such instances constitute masculinity challenges. In response, AMV Hell strongly asserts fans' status as sexually knowledgeable. It displays eroticized images of female characters with, depending on the video source, more or less explicitly pornographic natures. This continual repetition of sexual imagery parallels the sex talk that Pascoe (2007) and Messerschmidt (2000) observed among male high schoolers. The boys continually competed with each other by passing around (and inventing) stories of sexual activity with girls. These games of sex talk one-upmanship, like the collection of explicit sexual imagery in AMV Hell, "expresses boys' heterosexuality by demonstrating that they were fluent in sex talk, knew about sex acts, and desired heterosexual sex" (Pascoe 2007, 104). For "AMV Hell 3" (2005) and "AMV Hell 0" (2005), Zarxrax and SSG solicited crowd-sourced clips with a call "not to hold back…[editors] should make the most nasty, disgusting, or offensive things that they could. Nothing would be censored." The result, basically "a lot of Hentai [pornographic] videos," suggests that the desire to prove masculinity via the AMV version of sex talk was widely shared (note 6).

[5.4] Sex talk is one "confirmatory ritual" that Pascoe identifies in her fieldwork, a way in which male high schoolers established their possession of hegemonic masculinity. Here, hegemonic masculinity is above all defined by dominance and control over female bodies, "what boys could make girls' bodies do" (2007, 104). The editing of sexual imagery in AMV Hell follows the logic of sex talk confirmatory rituals. Images of female bodies are tightly controlled via beat and lip sync, video-making techniques that emphasize movement as well as the editors' technical proficiency (Close 2014, 207). One "AMV Hell 1" segment, for example, highlights the movement of breasts and butts in the fantastically sexual anime Eiken by synchronizing that movement with beats in the electronic progressive metal song "Penis Fly Trap" by Vomitron. This dynamic repeats over and over again, via the jouissance aesthetic of the video, continually confirming and reconfirming the editors and viewers' masculinity via their implied control over the characters' sexualized female bodies.

[5.5] The stereotype of fans as infantile hits male and female fans in different ways. For female fans, it ties into long-standing misogynistic discourses that define femininity as immature, childlike, and weak. For male fans, this stereotype evacuates their very claims to masculinity. As these fans clearly know well, masculinity is often associated with male bodies, but being biologically male is no guarantor of being masculine. Indeed, continually laying claim to masculinity comprised most of the public social interactions of male students that Pascoe (2007) observed.

[5.6] It is not hard to understand why male otaku might have been (even if unconsciously) eager to demonstrate their masculinity. What might be surprising, however, and more hopeful, is that anxiety and jokes about male bodies also appear in multiple segments of AMV Hell. The pairing of anime Berserk with the Annie, Get Your Gun musical's song "Anything You Can Do," for instance, stages a character who appears to be a woman and exults over being able to do anything better than the normatively male character. This includes, at the end of the segment, physically being a man. Such anxieties were rarely voiced by boys inside the high school, particularly in public spaces. The same Viewer's Choice awards that recognized "AMV Hell 1" for comedy and originality also gave out awards for Most Romantic Video, Best Dance Video, and Most Sentimental Video—genres that evince interests and public discussion far outside normative masculinity. In fact, the year before "AMV Hell 1," the Viewer's Choice contest recognized the comedy and lip sync proficiency of editor absolutedestiny's "I Wish I Was a Lesbian" (2003) (video 3). He uses the Loudon Wainwright III song to suggest that "there's some anime characters who really do wish they were lesbians because, let's face it, guys suck. Especially anime guys."

Video 3. absolutedestiny, "I Wish I Was a Lesbian" (2003).

[5.7] Although the video uses the concept of lesbian sexuality, the discussion is clearly about normative masculinity, its flaws, and the effects of those flaws on women. Such texts circulate, discussions occur, and social recognition rituals confer status in otakudom's shared social spaces but parallel the tender private discussions Pascoe (2007) recalls with male students about their feelings for their girlfriends—the same girls whose bodies they used publicly as masculine identity resources. These texts demonstrate that there are communally valued ways of being male, particularly a fannish male, which run counter to hegemonic definitions of masculinity.

[5.8] Acafans and fans themselves often rightly celebrate the way in which fandom can be a safe space for women. Slash and kink fan fiction, in particular, are ways in which female fans actively explore their sexualities and shape new discourses of femininity. As a longtime slash and yaoi fan, I agree with Zubernis and Larsen's (2012) conclusion that these practices can be immensely beneficial for women, particularly queer women, trying to understand their desires and realities and to work through past traumas. There is far greater potential here than in expanding women's access to masculinity as it is normatively defined, as Pascoe (2007) observed "basketball girls" doing by controlling other, more feminine, girls' bodies or as Monden (2010) argues that shojo critics do in neglecting the conventional shojo manga of ribbons, feathers, and wide eyes.

[5.9] Slash and yaoi are also, however, spaces where female fans assert their control and dominance over male bodies. In American media fandom, female fans, particularly slash fans, split off from male-dominated fan conventions and spaces early on. As has been well documented, they held their own cons, circulated their own periodicals, and vidded for a female-dominated fan community. American otakudom was smaller than domestic media fandoms, and the otaku ethic places great emphasis on acquiring and sharing source material, to the extent that "unlike fandoms around domestic [US] television, anime fans see their ability to access and acquire the media content as itself a unique marker of commitment and subcultural capital" (Ito 2012a, 283). Though internal divisions always exist, convention spaces and online fora such as Anime Music Videos were largely mixed gender (note 7). This is perhaps best illustrated by the AMV "Mystery Yaoi Theater 3000," created by Zarxrax of AMV Hell. This video stages two male fans watching a yaoi video that one has created with the purpose of relating to female fans (note 8). This AMV evinces an understanding of and proximity to female otakudom that contrasts sharply with Jenkins's 2006 finding that most male Star Wars fan video creators were unaware "that women were even making Star Wars movies" (Jenkins 2006, 161). In the same time period as Pascoe (2007) observed that male students adamantly refuse even to go to their school prom if a very outwardly feminine gay male student attended, male anime fans, already stereotyped as feminized, walk down artist alley hallways full of yaoi images and fiction.

[5.10] Female otaku could be cruel in mobilizing discourses of male shame and anxiety about their masculinity. Consider Viewer's Choice Award–nominated comedy video "Mission: Fanservice" (2007) (video 4).

Video 4. Autraya, "Mission: Fanservice" (2007).

[5.11] Editor Autraya writes that her AMV is "the story of the Otaku trying to get ahold of fanservice and there is a moral to this story…Well you'll see what that is in the last scene." The moral for the male otaku, depicted using military tech to get intimate, voyeuristic views of female characters, is to wind up face-to-penis with a naked man in a hot spring—canceling out male otaku's attempts to confirm their masculinity throughout the video.

[5.12] As a feminist who became a fan of anime in search of more agentic female characters than were available in mainstream American media, I see myself in Autraya's note to the video that she had to "beg/borrow/steal anime from several friends, because strangely enough I don't own any anime with fanservice…well not purposefully anyway." Fanservice, or gratuitous shots and images of female characters, is a fairly common aesthetic feature of anime. It irritated me every time I saw it and served as a constant reminder that I, as a female and even as a lesbian, was not the imagined audience for the texts that I loved. I consider "Mission: Fanservice" and the AMV Hell videos together here not to suggest that they somehow cancel each other out. The hegemonic masculinity repeatedly confirmed in AMV Hell has considerably more cultural scaffolding, both in the original anime sources and in their links to institutions of gendered oppression. But if we recognize the efficacy of female fans working through shame, producing slash, and recognizing desires that cause more than one fan to say, "Yeah, I am disturbing" when they reflect on kinks like being "fascinated and attracted by male suffering," then there is reason to believe it may be helpful for male fans to do the same (Zubernis and Larsen 2012, 73). If anything, AMV Hell reiterates the ugly shapes that discourses of normative masculinity place on male sexual desires. It also, along with the larger AMV and otaku ecology within which it thrives, displays complex human beings working through anxieties, desires, and social changes that include but are not reducible to those discourses.

6. The performance of effeminate masculinity

[6.1] In discussing AMV Hell, I have largely focused on otaku's attempts to fulfill the requirements of a depressing definition of hegemonic masculinity, one that centers heterosexuality and the control over women and their bodies. However, as the wider ecology of AMV editing and other videos suggests, American otakudom also fosters the development of alternatives to this toxic definition of masculinity. I move now to focus in on one such alternative: effeminate masculinity.

[6.2] The halls of anime conventions are populated by vibrant communities of cosplayers. As a fan practice, even in American otakudom's early years, cosplay tends to swap the gender dynamics of otakudom mentioned before. While people of all genders wear costumes to conventions and participate in activities like skits, group photos, and cosplay contests, a majority of cosplayers are women. Many of these women, myself included, crossplay male bishounen characters and sometimes strike poses, including yaoi-style ones, alone or with other fans for photos. These photos are uploaded and shared online.

[6.3] Male crossplay is less common, particularly in the United States. It is by no means unknown, however, and two male crossplayers (figure 1) became famous within, and somewhat without, otakudom: Sailor Bubba and Man Faye (note 9).

Figure 1. Image created by author in 2015 that puts together online photographs of Sailor Bubba (left) and Man Faye (right) posing at conventions in their costumes. [View larger image.]

[6.4] These two men regularly cosplayed as, respectively, the eponymous Sailor Moon (1999–) and Faye Valentine (2000–2007) of Cowboy Bebop (1998–2002). Both costumes liberally mixed masculine and feminine signifiers rather than attempting to exactly resemble the female characters: Sailor Bubba wore his blond pigtail wig over his beard, and Man Faye displayed body hair in the midriff and bare thighs of the revealing Faye costume. In this combination of bodies sexed male and performance gendered female, both fall into what Pascoe (2007) identifies as the fag position. Masculinity studies originally developed the concept of hegemonic and subordinate masculinities by considering the experiences of gay men, whose masculinities were continually culturally subordinated to those of straight men (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). Pascoe argues that LGBT activism has had some effect, to the extent that male homosexuality may or may not be pathologized depending on the situation and location, "but gay male effeminacy is. The lack of masculinity is the problem, not the sexual practice or orientation" (2007, 59). Rather than a lack of masculinity, I characterize these gendered performances as effeminate masculinity.

[6.5] Anime Expo staff actually banned Man Faye from attending the convention. After being forced to surrender his badge and leave Anime Expo 2004 as a result of supposed complaints from nonfans who saw him, Man Faye went to the 2005 convention and "after waiting for three hours in the registration line, right when I get to the tables, five security guards are waiting to prevent me from registering. I asked to talk to Con Ops, but they said no. I asked for a phone number to call Con Ops. They gave me what turned out to be a fax line" (Bamboo Dong 2005). Man Faye's narrative points to a connection between gender discourses and the discrimination he faced, saying that "if a woman can wear an incredibly revealing outfit, a man should be allowed to as well. I have no doubts that a girl wearing the SAME costume as mine would not have any trouble at all. In fact, I have photos of girls at the con doing just that and not ONE of them had any trouble" (Bamboo Dong 2005).

[6.6] Man Faye's statement in this interview that "not ONE" of the women wearing revealing costumes at conventions "had any trouble" highlights the complexity of both gender and sex at play here. Female cosplayers do, in fact, have a great deal of trouble. Like Sailor Bubba and Man Faye, those without idealized thin bodies are frequently shamed and their images appropriated for hateful memes. The "Cosplay Is Not Consent" campaign combats sexualized violence against cosplayers, most but not all of whom are female, at conventions. The project started by collecting photographs of cosplayers and con photographers holding signs with the slogan "cosplay ≠ consent" or, in the style of Project Unbreakable's work with rape survivors, signs on which they have written disturbing things that have been said or done to them while cosplaying (figure 2). The campaign has progressed into working with conventions to implement and enforce sexual harassment policies and to teach cosplayers strategies for protecting themselves, such as "escalated use of voice."

Figure 2. Photograph from the Cosplay Is Not Consent project of a cosplayer in a Poison Ivy costume, holding a sign reading, "Not asking for it (even though my boobs are great)"; the project's current Web site is Cosplay Is NOT Consent (http://cosplayisnotconsent.tumblr.com/). [View larger image.]

[6.7] By contrast, Man Faye transformed an instance of unwanted touching into part of his fannish lore through just such use of voice. At the second convention he attended, a stranger hit Man Faye on his rear, whereupon Man Faye instantly roared "HEY, WHO JUST SMACKED MY ASS!" (Bamboo Dong 2005). Man Faye then appropriated the stranger's gesture, asking his supporters to line up to spank him. This ritual sits in opposition to the games that Pascoe (2007) observed, wherein one boy would briefly perform a caricature of effeminacy and the others would run away to avoid being touched, a game similar to tag. Slapping Man Faye's butt is a public, consensual act of eroticized contact that denounces this stigma of effeminate masculinity as repulsive and contagious. However, it is an appropriation only available to people of male sex: those bodies are ideologically associated with control over sexual expression, while bodies sexed as female are assumed—or required—to be controlled by others, particularly in their sexual behavior.

7. Repudiation: Fat guys in sailor suits

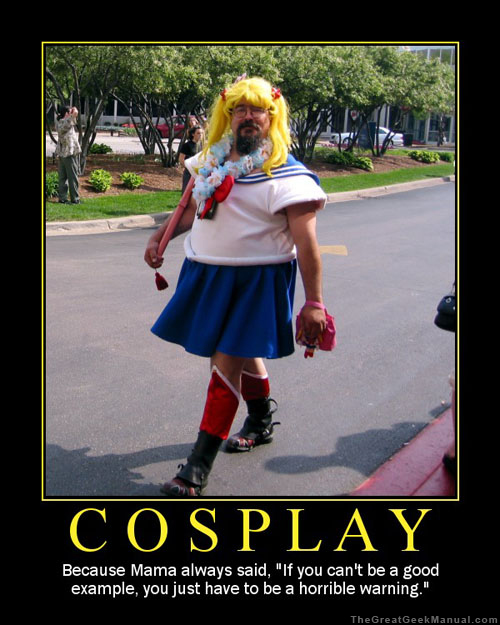

[7.1] Many fannish discourses around Sailor Bubba and Man Faye are remarkably cruel. Both regularly come up in "Best of" cosplay lists for the explicit purpose of being disavowed. Even Kotaku, a gaming and geek culture blog that explicitly aims to be a safe space for people of all genders, ethnicities, and sexualities, is decidedly ambivalent about Sailor Bubba. Contributor Brian Ashcraft (2012) wrote an article rounding up good Sailor Moon cosplay photos online entitled "The Tough Women (and Bearded Lady) of Sailor Moon" which collects "some—not all—of the best Sailor Moon cosplay the Internet offers, showing off the character's trademark sailor suits, footwear, headbands, wands, and beards [sic]." Though the canonical characters do not have beards, unlike the rest of the attributes mentioned, it is hard to read the strikethrough and the epithet "Bearded Lady," reminiscent of the circus freak, as affirming. This is particularly true when immensely hurtful memes circulate online (figure 3) (note 10).

Figure 3. Demotivational poster-style meme image showing Sailor Bubba walking across a street. The text reads, "Cosplay: Because Mama always said, 'If you can't be a good example, you just have to be a horrible warning.'" [View larger image.]

[7.2] These discourses resemble the repudiation rituals that Pascoe (2007) identifies, wherein "the aggressiveness of this sort of humor cemented publicly masculine identities as boys collectively battled a terrifying, destructive, and simultaneously powerless Other [the fag], while each boy was, at the same time, potentially vulnerable to being positioned as this Other" (157). By drawing a line between themselves and the nonnormative male crossplayers, such anime fans repudiate the specter of the obsessed, overweight, femininized weirdo and validate their own normative masculinity.

[7.3] The gaze from outside fandom is particularly significant here. Fans are often strongly aggressive toward "other fans who they believe are 'doing it wrong'" citing fears that those "doing it wrong" will make outsiders look upon fandom poorly (Zubernis and Larsen 2012, 125). It is remarkable how much fannish lore attributes restrictions on fandom to complaints from either unidentified nonfans, as in the case of Man Faye's expulsion from Anime Expo, or unverified stories of creators reacting badly to fannish texts involving gender and sexuality, as in the case of George Lucas allegedly attempting to restrict Star Wars fan work after reading erotic slash (Jenkins 2006, 158). Man Faye went considerably public with his attempts to change Anime Expo's policies, peaking with an appearance on The Tonight Show. Otaku continually critique him for "attention-seeking" behavior, consistent with Japanese cosplayers' disdain for those who wear costumes in order to draw attention to themselves (Okabe 2012a, 241). Similarly, while the Sailor Bubba meme circulates within and without fandom, its form posits an outsider view wherein Sailor Bubba represents all of cosplay rather than a particular parodic approach (Lamerichs 2011, ¶3.5). The Cosplay Is Not Consent movement, Man Faye, and Sailor Bubba are often targets of fans who "respond to perceived external criticism," like the public suggestion that gendered harassment is a problem within otakudom, with "reactive aggression whenever a fellow fan appears to be supplying evidence for outside conceptualization of fans as 'crazy, fanatic, obsessed, perverse, or stalkers'" (Zubernis and Larsen 2012, 127).

[7.4] Perhaps ironically, many of Man Faye and Sailor Bubba's defenders also rhetorically perform repudiation rituals. The difference is that they position Man Faye and Sailor Bubba firmly on the good, masculine side of the line. Isaac Sher (2011), a longtime con staffer, wrote an article reminiscing on his memories of Sailor Bubba. After posting a picture, he cautions readers to read the entire story "before you start making snap judgments, rude comments, or jabber about reaching for the brain bleach." He writes that Sailor Bubba "doesn't wear the suit because he gets some perverted jollies off of it. He likes Sailor Moon, sure, but he's not obsessed with it. He dresses up because IT'S FUNNY." The ironic stance puts Sailor Bubba on the safe, masculine side of the line, in control of his masculinity.

[7.5] He goes on to position Sailor Bubba as a true otaku and contributing fandom community member by pointing to Bubba's efforts as a volunteer for the AnimeCentral convention's security detail. One particular year, a con creeper drew attention to himself at AnimeCentral by brandishing handcuffs at cosplaying girls. As Sher (2011) recalls it, Sailor Bubba, holding his pink Sailor Moon Wand, "walks up to Handcuff Creep as if they were the best of friends. 'Hey wow, you've got cuffs! I've got the sex toy! Let's make this happen!' The creep took one look at Sailor Bubba, turned a distressing shade of purple and orange, and bolted…never to return, and Bubba just kept on walking, smiling and making sure everyone at the con was having a great time." These kinds of stories and defensive rhetoric figure Sailor Bubba as one of the masculine boys that Pascoe observed performing imitations of fag behavior. These performances assure "themselves and others that such an identity deserves derisive laughter" and that they do not really have such an identity because they are able to easily cast it off (Pascoe 2007, 61). Arguing that Sailor Bubba or Man Faye are ironic, joking, and being funny downplays the transgressive nature of their visual depictions of feminine men—even better, defenders argue that these fans are so hypermasculine that they can take on these performative identities to discipline other men, like the con creeper, whose sexuality is out of bounds and threatens the convention community.

[7.6] Like the confirmatory rituals of AMV Hell mentioned earlier, fans are almost certainly not conscious of these repudiations as such. Many, like con staffer Sher, are motivated by truly laudable desires to protect and defend the real men they have met and befriended from vicious public ridicule. Others, initially repulsed by the specter of the effeminate masculinity embodied in these gender performances, have come to enjoy their humor or see the men as crusading for equal rights within otakudom as thus improving rather than disparaging, fandom. One commentor on Man Faye's interview with major otakudom news site Anime New Network, for example, writes, "I feel sorry for Man-Faye getting banned by AX [Anime Expo]…I used to be one of those fans who used to hate him, but not anymore." Magicreaver, a participant in an Anime Central Con forum poll pitting Man Faye against Sailor Bubba, voiced similar sentiments: "My first ACEN [Anime Central con] I remember seeing Sailor Bubba and being creeped out…and then last year I didn't see him and was disappointed, ah how one matures (is that really maturing) over the years."

8. It's right, but it feels wrong. It's wrong, but it feels right: Toward a conclusion

[8.1] Constructively engaging with nonnormative masculinities and the people performing them is, indeed, maturing. Or at least it was for me. I've never had the pleasure of meeting Sailor Bubba or Man Faye, but they are only the most visible and widely discussed incarnations of male crossplay tradition seen at many conventions. As an anxious teenage female fan attending my first convention, I remember seeing a large man dressed in a sailor suit and feeling a hot flush of shame and horror: is that what we are? Somewhat overweight at the time myself, I had not had the confidence to cosplay. My shock was of recognition and fear that perhaps the stereotypes told about fans, which I had vehemently rejected, were true after all. Throughout the course of the small con, though, nothing bad happened to or around the sailor-suited man. People seemed to be having fun, and he was there with friends, wandering around the viewing rooms and dealer's hall like everyone else. When I came back for my second convention, I wore my first costume. My experience here falls in line with Lunning's argument that through cosplay "fetishized imaginary identities supplant the real identity through the crisis and trauma of abjection…securing for the cosplayer a temporary symbolic control and agency" (2011, 77). This is echoed by the experiences of many fans who have written or spoken to Man Faye, sharing that seeing him inspired them "to do everything from wear the racy costume they never had the nerve to wear, to come out of the closet to their parents" (Bamboo Dong 2005).

[8.2] Defending the concept of maturing is an unusual stance in the context of queer theory. Edelman defines and critiques maturity as always privileging the future over the present, prioritizing the (forever deferred) culmination and realization of ultimate meaning over in-the-moment pleasure and joy. What I mean by maturity here is the opposite: sinthomosexuality. It is identity without anxiety. A mature masculine identity, by my definition here, does not constantly strive to prove itself by living up to an imagined masculine ideal. It relinquishes the need to police boundaries of ought to or should be. It is the space of jouissance and re: reflecting, reworking, refeeling, rewatching, redoing without an end goal in mind. A mature, sinthomosexual masculinity in this sense "scorns such belief in a final signifier…insisting on access to jouissance in place of access to sense, on identification with one's sinthome instead of belief in its meaning" (Edelman 2004, 37).

[8.3] Particularly from a feminist perspective, this might seem an overly breezy conclusion to a discussion of masculinity. The discourses of masculinity circulating throughout American otakudom were—and in many ways continue to be—deeply problematic. As much as fandoms are subcultures, they are still attached to the larger American culture and to the workplaces and schools that fans attend in their regular lives. It would be frankly astonishing if the discourses of gender and sexuality current in the mainstream, with all the problematics delineated by feminist and queer theory, did not come with many fans into the separate space of otakudom. But as I have shown, much of the violence of masculine privilege stems from masculinity's need to continually prove itself worthy of an ideal, to reconfirm itself with a very particular goal in mind. This is one instance of reproductive futurism's violence, the demand that the present always be dedicated to the service of an imagined, perfect future.

[8.4] Fan cultures are uniquely well-equipped environments to foster sinthomosexual masculinities and, as research on cosplaying women argues, nonhegemonic femininities (Lunning 2011, 75–76). Cultural practices of distilling thoughts, identity experiences, and narrative into artifacts, like AMV's, and performances, like cosplay, allow for a perspective on these concepts and experiences that we do not otherwise have. Fannish objects are circulated, discussed, imitated, critiqued, parodied, and all of these things again. These practices displace the ultimate focus on meaning—the one true meaning of a text—in favor of focus on the texts themselves and the irreducible particularity of each person's relationship with them: play rather than perfection. To the extent that fans of all sexes have an interest in masculinity and to the extent to which it shows up in the source texts, this discussion, circulation, and play allows for the creation of many masculinities to emerge and displace the hegemonic masculine ideal. This development of alternative masculinities is essential for culture to move toward more equal gendered relations (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005).

[8.5] These practices are certainly not the whole of fan culture. For one, there is no value here on technical perfection or social critique, which are integral to many fan practices—acafans and fannish activists did not invent them for the purpose of respectability and advocacy. Jouissance is also not the space of fan wank, forum drama, and shipping wars. Differentiation, judgment, and the policing of boundaries, whether by academic critics inscribing a canon or by fan fic authors crusading against Mary Sues, are practices of futurism rather than of jouissance. I do not argue that we should abandon analysis or wank—as if we could! Just as Edelman argues that jouissance, even denied and stigmatized as "perverted jollies" to borrow Sher (2011)'s term, is always present in human society, I argue that there will always be a place for futurism and a value on creation. Indeed, the very practice of writing an academic article or book requires a focus on meaning, logic, and progression that is alien to jouissance. But at this time when fan studies is becoming legitimized within the academy and fannish practices folded into the commercial mainstream, it is essential that fannish cultures retain their emphasis on jouissance in order to remain catalysts for a desperately needed reconfiguration of masculinity.