1. Introduction

[1.1] Fan fiction is an emblematic fan practice. It has been a focus of study for over two decades, and it remains a vivid example of how fans reimagine and reinterpret their object of fandom. However, the practice is usually thought of as limited to so-called media fans—fans of TV series, films, and books—and not part of the practices of other kinds of fans. For example, sports researchers think that "despite meeting independently and writing their own fan materials, sports fans contrast with the likes of Jenkins's (1992) Star Trek fans' creative writing, which was inspired by and exceeded the 1960s series' social liberalism, because they cannot creatively refashion the cultural commodity" (Free and Hughson 2006, 92). Fan fiction, to most, is not something that sports fans do.

[1.2] However, a look at any multifandom fan fiction archive would show differently. Sports fans are writing fan fiction—fan fiction that is not particularly distinct from the fan fiction being written by media fans. Of this, slash fan fiction based on high-level European football is some of the most enduring. The LiveJournal community Footballslash has been in operation since 2002, with predecessors in e-mail mailing lists, and it continues to be active today. The existence of sport fan fiction is the result of two things: the increased mediatization (Hjarvard 2008) of high-level European football, in which the major leagues have become increasingly influenced by and reliant on the resources of the media, and the expansion of fan fiction practices. Football fans increasingly experience football through the media and as a media narrative, especially at the highest level, where media coverage is the most intense and live football is the hardest to access in person (Sandvoss 2003).

[1.3] Yet researchers have often been reluctant to consider fan practices that have arisen as a result of this because "many commentators have assumed that such cultures of engagement with football will be full of (predominantly middle-class) people whose interest in the game is simply a knee-jerk response to the marketing activities of clubs and corporations" (Moor 2007, 139). Media-based fans (and fan practices) are seen as a threat to real fandom, and a mediated understanding of the game is considered to be a recent development. Scholarship on football fans' engagement with media, especially new media, therefore often serves to prove how traditional and authentic these fans actually are (Gibbons and Dixon 2010; Rookwood and Millward 2011; Williams 2012). Here I look to provide a counterpoint to such perspectives by analyzing how the changing nature of football—and fan fiction practice—creates new ways of engaging with it, one that expands the idea of whom football is for.

[1.4] My study uses a combination of ethnographic (including autoethnographic) analysis and textual/content analysis of the football fan fiction community and its works. Its starting point is participation in the Footballslash community and its supporting sites, with a focus on the 2011–12 European football season. These supporting sites included Footballmeta, Football Kink Meme (Footballkink2), Touchline, RPS Football Fiction—Comment Porn (Commentporn), and Cornerflag, as well as several personal blogs of Footballslash participants and conversations with football fan fiction writers about their works and their wider football fandom. I analyze stories, story prompts, and general fan discussion regarding football, slash fandom, and their intersection. I have selected one piece of fan fiction as representative of the kind of work that football fan fiction writers do to transform the football narrative. Although a close reading of a single story does not reflect the wide range of interpretations that fans make about football through fan fiction, this analysis permits a useful illustration of the form and provides coherence to the discussion of different aspects of football slash fan fiction.

[1.5] Additionally, in April 2012, I posted a survey to Footballslash and Footballmeta, with results kept anonymous. Fifteen questions regarding demographic data, football viewing habits, and the discovery of Footballslash, both the community and the practice, were asked, and 67 participants responded. At the time I administered the survey, the community had a membership of approximately 2,900, although, because of the longevity of the community and the private nature of LiveJournal reading, it is difficult to judge how many were active members that still read and participated at the site. This survey was used to get a better sense of the community's general relationship to both football and media fandom.

[1.6] Here, I ask how football slash fan fiction came to exist and what purpose it serves for football fans in the contemporary media environment. To answer this question, I analyze the origins and implications of understanding football as a media text and narrative, and I address why fans are interested in writing slash fan fiction about football players. As a result, my research also provides an analysis of the still-controversial practice of real person slash, fan fiction written about real people as opposed to fictional characters. I thus present a different way of understanding sport and sports fandom—one that bypasses the arguments around authenticity and tradition to show other ways that sport can be appreciated.

2. Football as cult media

[2.1] Marcus Free and John Hughson state that the nature of sports resists fan fiction because its "structures and rules generate uncontestable representations of contests as 'results'" (2006, 92), and thus the unambiguity of these factual events resists fan interpretation. This is generally the way sport and sports fandom are situated: in comparison to the texts of media fandom. This traditional view of sport is that it is about who won or lost and who played well or poorly, which are issues that cannot be disputed. Sport is an athletic performance with clear outcomes, and therefore it is not open to interpretation in the manner of media fan practices.

[2.2] Yet today "it is increasingly difficult to maintain a purist definition of sport as athletic performance, given that, however important it might ultimately be, it could not be sustained without all of the other modes of media representation and the involvement of constantly shifting audience formations" (Rowe 2011, 520). Football, along with other popular sport, has become mediatized (Hjarvard 2008), reliant on the media's resources for income and visibility. While this has been an ongoing process since the sport was first codified in the late 1800s, it reached a new phase in the early 1990s with the rise of satellite channels that broadcast all (or nearly all) football games in their entirety (Sandvoss 2003; Boyle and Haynes 2004). Football on television is not simply transmission of a sporting contest: it is "part of popular television, functioning under the sign of entertainment, and therefore also has to frame its own representations in the context of the values that constitute 'good television'" (Whannel 1992, 106). This has not been without controversy. The increased profile and wealth of football thanks to television, with the continuing need to appeal to sponsors and the general public, has led to the "sense on the part of many that the game has lost its soul to an alliance of merchandisers and 'inauthentic,' Johnny/Jackie-come-lately supporters" (Wagg 2004, 1). Compared to this inauthentic new fan, easily swayed by marketing and celebrity, the ideal authentic supporter avoids media representation in favor of "a long-term personal and emotional investment in the club" (Giulianotti 2002, 33) that is focused on physical presence instead of learning about the game through television.

[2.3] However, even this ideal authentic supporter sees football as more than results and is therefore influenced by the media. The structure of contemporary football relies not just on reportage but on its never-ending narrative, its focus on strong, individual players, and its creation of personal connections to a team's fortunes. In football, "no single game ever represents the game for players or spectators" (Hughson and Free 2006, 76), as each game is part of the narrative of the season or the tournament, and each season or tournament is part of the seasons or tournaments that came before it and that will come after. These games rotate around the comings, goings, and doings of the players (and managers) that perform in them. In combination, these two elements are what keep football engaging and entertaining to the majority of its fans. They are heavily discussed and promoted in all facets of the football media, contributing to an ongoing, long-term interest in the narratives by the fans who continually discuss and debate them. As a result, to truly understand football, one must look at not only the 90 minutes of the match but also the surrounding media, which function as necessary paratexts.

[2.4] Jonathan Gray argues that paratexts—texts surrounding and supporting a main text, such as a movie trailer, DVD extras, or fan works—are an integral part of how we understand the main text, as "a film or program is but one part of the text, the text always being a contingent entity, either in the process of forming and transforming or vulnerable to further formation and transformation" (2010, 7). If we take the game as the main text, paratexts or overflow material (Brooker 2001) are crucial to understanding football: without the context provided by newspapers, televised discussion shows, and so forth, the game would have no meaning. In the past several decades, corresponding with the amount of televised football available, the amount of paratexts surrounding football has grown exponentially (Cleland 2011). What's more, new media practices have shown that fans can shape these narratives themselves, creating blogs, podcasts, and message boards that form and transform the narrative space. Football is therefore a multiauthored text, and increasingly, fans are among the authors.

[2.5] The narrative style of sport is frequently referred to as a male soap opera. This pronouncement is often made with some level of irony, as it juxtaposes the common belief in the lack of quality or importance of a soap opera with the importance given to televised sport. O'Connor and Boyle considered the relationship between soap operas and sport by comparing "the characteristics they have in common such as their broadcasting at frequent and regular intervals, their indeterminate (continuous) life span, their range of characters, and the introduction of multiple narrative strands which reach various stages of resolution" (1993, 3). Indeed, the two genres have many similarities, both in form and function for their respective fan bases, especially as a result of their long-running nature, with story lines that have the capability to span across decades in a manner unlike other forms of popular narrative. Players, managers, and teams all "have a past, a history, which the audience is aware of, and through which they are read" (Whannel 2002, 152). Soap operas, several of which have been running a continual story line since the 1960s or earlier, can match this in a manner unlike other forms of television.

[2.6] Yet it might also be fruitful to think of sport, and football specifically, as an analogue of a different but related form: cult television. Gwenllian-Jones and Pearson, in the introduction to their edited book on the topic, describe the form as featuring "a potentially infinitely large metatext and sometimes the seemingly infinite delay of the resolution of narrative hermeneutics" along with "interconnected story lines, both realized and implied, [that] extend far beyond any single episode to become a metatext that structures production, diegesis, and reception" (2004, xii). Matt Hills defines cult texts as featuring "hyperdiegesis: the creation of a vast and detailed narrative space, only a fraction of which is ever directly seen or encountered within the text, but which nevertheless appears to operate according to principles of internal logic and extension" (2002, 137). Cult media, and especially cult television, are considered to have complex, potentially infinite narratives, with questions that might never be truly answered, even when some are resolved, and a world and story that are never fully revealed to the viewer.

[2.7] Within a cult text, "there is always a deficit between what is (or can be) shown and what the avid audience wants to see, explore, develop and know" (Gwenllian-Jones 2000, 13). The thought that fans can fill in this deficit themselves led to the creation of fan fiction, which originally developed within cult fan communities (Jenkins 1992; Bacon-Smith 1992). It also led to the more widespread use of paratexts like guides to a series' world. Cult texts are seen as polysemic; they "present the reader with a multiplicity of possible interpretations which are consciously realized by the reader" and "allow for different readings by different readers" (Sandvoss 2005, 125–26). Fan fiction and other fan-made or fan-oriented paratexts are one result of this polysemy; with them, "there is an acknowledgement that every text contains infinite potentialities, any of which could be actualized by any writer interested in doing the job" (Derecho 2006, 76). There might be an official producer, but there can be multiple authors of the text's meaning.

[2.8] As mediatized football connects to other media texts, it becomes possible to see the ways its potentialities can be explored. Sandvoss (2003, 2005) discusses the polysemy of football clubs and how the same club can have different meanings to different fans, but the narrative itself is also polysemic, and the growth of football paratexts shows that it can be interpreted by anyone. Football fans who discover fan fiction or fan fiction fans who discover football see the potential of the world of European football. Its narrative is complicated but is focused on a single question—who will win—that is then applied to the game, the season, or the tournament, and that is instantly deferred again as soon as it is resolved, with the new questions maintaining continuity with the old ones. Intertwined with this overarching narrative are countless other story lines, interconnected into the main question when necessary, and featuring a wide cast of interesting characters. Fans recognize the narratives promoted by the football media for what they are and utilize them in the manner of other narratives.

[2.9] "Filling Up the Space," a football fan fiction story by Luxover (2011), is an example of how the narrative of football is transformed via fan fiction. Here, Liverpool FC's 2009–10 season is reconstituted as the backdrop of the breakup and eventual reconciliation of a romantic relationship. It utilizes points in the actual events to show how Steven Gerrard, Liverpool's native-born captain, deals with both the disappointments of his failed relationship with Xabi Alonso, the Spanish midfielder who played for Liverpool before transferring to Real Madrid before the start of the 2009–10 season, and the disappointments of a poor season. The plot centers on Gerrard and Alonso, after their breakup at the beginning of the story, dividing the world between them so that they do not see each other, and the both of them then breaking the rules they set with each other. The well-documented events of the football season provide the framework of the story, as shown in this excerpt:

[2.10] October rolls around and Liverpool loses to Chelsea; Stevie feels the loss somewhere in his chest and so he goes home and thinks, It shouldn't be this hard. It never used to be this hard.

[2.11] To keep himself busy, he empties his closet, makes a pile of everything that he doesn't want anymore and adds to it until everything he owns is thrown on his bed, pants and shirts and ties and two watches. He finds a pair of cufflinks that used to belong to Xabi and he wants to laugh. He does laugh. They're Xabi's favorite pair, white gold and plain and so completely boring that Stevie's heart flops a little; he's excited.

[2.12] Stevie puts the cufflinks on his dresser top and takes a picture of them with his phone. He sends it to Xabi, says to him, Finders, keepers.

[2.13] Xabi says, That's not on the list. He's terrible at this game.

[2.14] Stevie puts everything back in his closet and goes downstairs to watch crap television.

[2.15] Writing after the events of the season (the story was posted to the Footballslash community on September 26, 2011), Luxover intertwines the professional and personal disappointments of Steven Gerrard, with both achieving equal importance. In doing so, Luxover offers a new version of the well-known events of the season. For Luxover, the events are a media text to be expanded rather than a factual event that has ended.

[2.16] While this might be a nontraditional reading of the text of football, it is not one that comes from outside of it. Football is constructed in the media in such a way to keep viewers "interested in the next 'instalment' and provide an ongoing sense of the importance and uncertainty of upcoming events" (Kennedy and Hills 2009, 76). The presenting of football as comprising installments or episodes has been part of its makeup since the earliest days. The football press, fully in place by the early 1900s, encouraged its readership to see the football seasons as ongoing, something that they would need to keep buying papers to follow and that did not end when the whistle blew. The presentation of football on television makes this connection even more explicit. In scheduling terms, football functions almost exactly like a television show: games at a set time, once or twice a week, with a break in the summer. It also feels like a television show, "combining the spectacular physical, often violent elements of action drama with the detailed characterization, emotional concentration and relational emphasis of 'human' drama" (Rowe 2004, 185).

[2.17] Within this presentation, however, there is significant missing information. The viewer sees very little of the players/characters outside of their work space. While there is a large and increasing amount of information about both football and football players, there is still a necessary limitation on what is shown. Fans who have experience with fan fiction recognize these unseen parts of the text as something that can be filled in themselves. Most Footballslash readers and writers had previously written or read other fan fiction, and it was this experience that made them look at football as something that could be likewise transformed. As media fans and fan fiction writers, this is what they have learned to do.

[2.18] Football fan fiction expands the emotional as well as the narrative space of football. As discussed by Kennedy (2000), football has a masculine address and focuses on what are considered masculine traits. The game is presented in a realistic style, and much of the commentary, both during the game and from pundits afterward, focuses on things that did or did not happen—the traditionalist view of what sport is. The more casual modes of address within football media, which takes the form of banter between the analysts or commentators, "approaches intimacy without engaging in the personal" (Kennedy 2000, 77) by focusing on triumphs or disappointments in the player's professional life, such as wins or injuries in the past, or direct reactions to game events. The narrative of football is masculine, whereas "emotions and sexuality [are] part of the domestic sphere and the domain of women" (Whannel 2002, 101). While anger or joy in relation to actions in the game might be acceptable, more subtle emotions are excluded.

[2.19] One use of football fan fiction is to rectify this exclusion by writing the emotional lives of football players back into the text. The Steven Gerrard of "Filling Up the Space" is at turns melancholy, proud, and happy; he misses Alonso, relies emotionally on his friend and teammate Jamie Carragher, and spends time reflecting on what Liverpool FC means to him. The emotional life that is left unrevealed within the actual text of football takes a central place within the story, providing it with its meaning. The reader understands Gerrard's hurt after the loss against Chelsea—a loss that somehow seems more painful than other losses—and can contextualize it within the relationships Gerrard has as well as the problems with the way Liverpool has been playing. Writing fan fiction becomes a way to give football and its narrative the emotional impact that they lack. Recontextualizing masculine genres into more feminine forms has long been standard in fan fiction, with the shows popular in the early years of the practice, like Star Trek (1966–69) and The Professionals (1977–83) considered to have a masculine address as well. In this, football fan fiction hearkens back to the origin points of the form rather than being a radical shift in subject matter for fan fiction.

[2.20] It must not be forgotten, however, that the writers of football slash fan fiction are football fans. By all indications, they all watch football regularly; they know the rules and traditions of the sport and its fan practices. Writing slash fan fiction is an understanding of football as a narrative form to be enhanced, but it sits together with the understanding of football as a sport. Neither fully transcends the other. "Filling Up the Space," for example, utilizes the terminology and description of football as a metaphor:

[2.21] Stevie remembers all of that as he watches Xabi get subbed off, and so he takes out his phone and he sends him a text.

[2.22] You're always looking for Kaká, he types, when Guti's always open to your left.

[2.23] He doesn't hear back until hours later, long since the match has ended and the players have gone home.

[2.24] Kaká plays where you played, Xabi says. You were always open even when you weren't.

[2.25] And Stevie doesn't know what to say to that, because sometimes he looks for Xabi when only Lucas is there. He wonders if Kaká knows what he's got.

[2.26] Narrative and sporting performance are not separated. Rather, they play off each other, with the knowledge of sport enhancing the verisimilitude of the story and working itself into its emotional core. The description of Alonso's and Gerrard's playing style becomes possible through the author's familiarity with televised football, providing it with an extra layer of meaning and explanation.

3. Football as slash fandom

[3.1] The core of "Filling Up the Space," however, is in the relationship between Gerrard and Alonso. In this, it fits the conditions and norms of the genre. Fan fiction generally, and especially slash fan fiction, is built upon relationships. While recent scholarship (Keft-Kennedy 2008; Tosenberger 2008) has challenged the early interpretation of slash fiction as an ideal romance (Kustritz 2003; Salmon and Symons 2004) where "sex occurs within a committed relationship as part of an emotionally meaningful exchange" (Salmon and Symons 2004, 98), it is still a form that focuses on the relationship, of whatever type, between the characters utilized. Whether the relationship is antagonistic, friendly, or even an ideal romance, it is the exploration of it that drives the vast majority of fan fiction practices. Slash becomes a way to reinterpret the football text to focus on relationships and emotionality, which, as previously mentioned, are not prominent in the mainstream presentation of sport.

[3.2] "Filling Up the Space" is no different. It speculates on how Steven Gerrard would have felt after losing games to Chelsea and Sunderland and allows the author to work through her own feelings about Liverpool FC, but it is also about the romantic relationship of Gerrard and Alonso. They break up at the start of the story, spend the length of it circling around each other, and reconcile at the end. The actual events might provide a framework for the author to build upon and work around, but the focus is the imagined romantic relationship between Gerrard and Alonso.

[3.3] In this, "Filling Up the Space" joins hundreds of other fan fiction stories detailing and exploring Gerrard and Alonso's romantic relationship. This pairing is the most popular in Footballslash, with 1,499 uses of the tag in the community as of February 2015 (the next most popular has 1,365 tags, and the third most 747). It is also among the most enduring, with stories about their relationship first appearing in late 2005 and continuing to be posted frequently, including at a newer fan fiction archive, Archive of Our Own, where it is the third-most popular male slash pairing. Despite Alonso's transfer from Liverpool in the summer of 2009, separating him from Gerrard, the pairing continues to thrive. It is far from the only pairing popular within the community, but its continued prominence as other pairings fade in popularity and new ones grow makes it an excellent case for exploring how relationships between footballers are interpreted in fan fiction.

[3.4] Alonso and Gerrard were teammates for 5 years at Liverpool FC, one of the most popular clubs in the widely watched English Premier League. Alonso was signed from his home club in Spain, Real Sociedad, in 2004, while Gerrard had grown up at Liverpool, joining the youth team at age 9 and signing his first professional contract with the club in 1997. On the field, Gerrard and Alonso played in complementary positions in central midfield, bringing them into regular contact with each other. However, the pairing did not establish itself until after Liverpool's win in the 2005 Champions League final in Istanbul, although they both had a presence in the community and were well-respected and well-recognized players among football fans of all varieties. In the Champions League final, Liverpool were losing 3–0 to the Italian superclub AC Milan at halftime, only to come back in the second half to tie the game 3–3 and eventually win the trophy on penalties. Both Alonso and Gerrard scored goals during that decisive half, with Gerrard receiving Man of the Match acclimation afterward. During the trophy presentation and celebration after the win, they briefly kissed, a moment that was filmed by the circling television cameras.

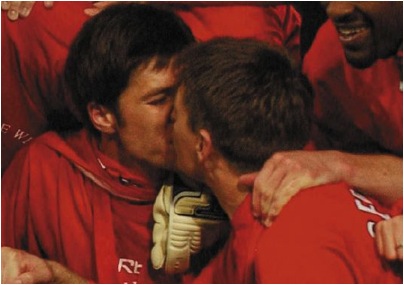

Figure 1. Kiss between football players Steven Gerrard and Xabi Alonso at the 2005 Champions League final in Istanbul after Liverpool's win. [View larger image.]

[3.5] In video, the moment is brief, a peck of the lips, with the two laughing afterward. As a still image, however, it becomes more intimate, resembling images of romantic kisses from other media. The viewer of such an image can ignore how brief and joking the moment was. As a photograph, it looks like a genuine romantic moment between the two men. The video might provide context and show what actually happened, but the fans overwhelmingly prefer the still image because it more closely mirrors what they want the moment to be. An image of these two players, already known within the community, in such an intimate pose, proved to be an inspiration to authors and potential authors. As it made its way to Footballslash and its users, the pairing picked up in popularity.

[3.6] These kinds of images are powerful within the community and provide much of its impetus. They are not limited to Alonso and Gerrard; the visual conventions of football, where players are frequently photographed embracing or otherwise in physical contact, inspire writers and readers. Slash fan fiction is essentially the eroticizing in fan-produced fiction of what Sedgwick referred to as male homosocial desire: "the whole spectrum of bonds between men, including friendship, mentorship, rivalry, institutional subordination, homosexual geniality, and economic exchange" (1984, 227). As Sedgwick (1985) explains, this has a long tradition in literature, and its history is frequently drawn upon when creating new works, particularly pop cultural works. Star Trek, for example, builds upon "the friendship of two males" (Selley 1986, 89) that characterizes much of American literature—two men with contrasting but complementary personalities exploring the wilderness (universe), with a great bond that cannot be matched by any other potential companion. It was this relationship between Kirk and Spock that led to the first media slash fan fiction, where "the fan has recognised the ambiguous possibilities of Star Trek and comprehended them as referencing the ambiguous area where the homosocial codes begin to be transgressed and friendship moves towards desire" (Woledge 2005, 246).

[3.7] Visual aspects are key to this interpretation. The way two characters look at each other is considered to be one of the enduring symbols of romance, carried on throughout different media eras. Eye contact, expression, and length of gaze all have significance. Viewers have learned to interpret these looks as romantic, even if nothing is specifically said in dialogue about their relationship (Bacon-Smith 1992). Within television and film with strong homosocial relationships, however, the use of eye contact and certain expressions are as likely to be shared between the two male characters as between a male and female character. Fans of the Kirk/Spock romantic pairing recognized "shots in which Kirk looks at Spock in the way a hero might look at a heroine" (Woledge 2005, 243–44) and read them as romantic, especially because Spock was a much more interesting character than Kirk's nondescript and underwritten female love interests presented within the narrative, and one that fans already had an understanding of. Once this potential reading was understood within the media fan community, it spread to other media narratives with relationships that could be read as homosocial.

[3.8] In contemporary media fandom, the idea that "there is a 'homoerotic subtext' revealed in the way certain male characters look at one another has become so familiar within fandoms that it is even possible for slashers to speak of such looks as 'subtexty'" (Allington 2007, 48). The practice of slash fan fiction since its beginning is based on "the images the viewer sees on the screen, and the way women read those framed images" (Bacon-Smith 1992, 232), which function alongside textual discussions of the relationship between the two characters. Once a fan learns how to see the homosexual subtext in the homosocial relationship, seeing it anywhere becomes possible. As Busse puts it, "Slashers are trained to tease out homoerotic subtext in the texts they encounter" (2006, 208).

[3.9] As slash fan fiction grew as a practice, the relationships that could be interpreted this way grew to include nonfictional, or real person, relationships. In its earlier years, "fandom…maintained an ethical norm against producing erotica about real people rather than fictional characters" (Jenkins 2006, 142). Coppa (2006) disputes this somewhat, noting that Duran Duran fan fiction was circulating in 1991, but she also notes that the authors were unlikely to come from regular media-based fandom and did not realize that it was taboo. However, this proscription became impossible to enforce as the practices of fan fiction expanded online and became accessible to a wider range of fans. These fans either didn't learn or didn't care about the taboo, finding the exploration of the homosocial relationship more interesting than maintaining it. Heavily mediated real homosocial worlds, such as that of boy bands or reality television, presented the same subtexty images and close relationships as fictional narratives, and proved just as open for exploration. While still controversial in some circles, in general, real person fan fiction or real person slash is accepted as part of the fan fiction landscape and is often offered alongside fan fiction (Busse 2006; Flegel and Roth 2010). The writers and readers of Footballslash came to it because they recognized the slash potential of football and "knew it had to exist," as one of my survey respondents put it. Even if fans' previous experience in fandom had been entirely based in fictional texts, they didn't see much difference between the Lord of the Rings franchise and the English Premier League. Both are media texts open for transformation, and most importantly, both are mostly homosocial worlds with plenty of opportunities to read homosexual subtext.

[3.10] Football, and sport in general, is one of the primary places that homosocial bonding is expressed within Western popular culture. Whannel discusses how, since its early days, "sport was for the boys, with the role of women decorative" (2002, 67). While women might now be allowed to play sport, and football is a popular sport for women to play, the presentation of top-level professional football in the media is one without women. Women are not on the field, the bench, the training grounds, the dressing room, or any the spaces that make up the world of football in the imagination. Some partners of the players (so-called WAGs) might have celebrity careers of their own, but within the football text, they are relegated to a familiar support or decorative role or are erased entirely. They do not act on the field and are rarely encountered in the paratexts. Football is "embedded largely in masculine exclusivity; in male groups" (Whannel 2002, 137).

[3.11] If women are mostly absent in the presented lives of football players, men are everywhere. As teammates or rivals, players are supposed to develop strong connections to these other men who make up their world. Teammates, for example, are supposed to be loyal to, and friendly with, each other. Much of the overflow material of football is dedicated to showing these friendships, either directly (interviews where players are asked questions like "who is the best dancer at the club" or "who takes the longest in the shower") or indirectly (players shown in the training ground joking and laughing with each other). They spend a great deal of time together and are often separated from family and other nonteammates at training facilities, away games, or tournaments. Even the sport of football itself, the main text, is built around the necessity of men interacting and working together. One player cannot play the game himself; he has to pass the ball to his teammates and work with them in order to obtain success. When a goal is scored, he does not celebrate alone but with his teammates. Homosocial connections make up what football is. Even when players are antagonists, placed in opposition to each other rather than expected to work together, they are still placed in a homosocial relation. These relations are presented visually—two (or more) players embracing after a goal is scored, players staring at each other antagonistically, as if ready to start a fight—and textually, with players talking about who their friends are or voicing their displeasure with an opponent. The codes of interaction between men that slash fans have learned to read as homoerotic—eye contact, physical contact, embraces—appear regularly in football photography. These moments might be fleeting in the actual game, but they are frozen in time via photographs or GIFs, constantly available for fans to look at and reinterpret.

[3.12] This homosociality makes football attractive as a source text for slash fiction. While many of the Footballslash participants were long-term football fans, many others came to it through media fandom. When encountering football, they found an attractively homosocial environment made up of attractive and homosocial men that offered a new setting and characters to which to apply the familiar textures of slash fan fiction. The isolation and high emotion of the world echo the so-called intimatopic environments described by Woledge, found in text that "emphasizes homosocial bonds through the depiction of the loyalty between two men who live and work in a more or less homosocial community" (2006, 100). While not all football fan fiction is intimatopic in Woledge's strict sense of the term, the environment is similar to this foundational form of slash fan fiction. It also offers the variety of slash pairings that Tosenberger (2008) sees as being part of the appeal of Harry Potter (books 1997–2007; films 2001–11) slash fan fiction, from the traditional buddy slash to enemy slash to power slash, but with an even greater number of potential pairings due to its large size. Additionally, the high-pressure, exclusively homosocial environment of professional football, filled with highly physical young men, is a space that that, like the boarding school of Harry Potter, already has a long-standing homoerotic reading (Pronger 1990) and provides a range of ways for strong homosocial relationships to move to homosexual desire. These fans' appreciation of football's fan fiction potential led to their becoming fans of it as a sport. For those who came to Footballslash as football fans already, the community provides a space to discuss aspects of football and footballers that are not generally discussed in mainstream football communities, and to appreciate it as a (slashy) narrative as well as an event.

[3.13] Therefore, the image of the kiss, as it became known, provided a base that fan fiction authors could build upon. Images of Alonso and Gerrard touching, hugging, or looking into each other's eyes, readily available through the celebration of goals, consolation after defeat, or simply playing around at training, also easily fit into the subtexty category that slash fan fiction fans have learned to recognize. Constant repetition of these images across fan blogs reinforced the idea that there is a romantic relationship to write about. This was added to information received from the football media, drawing from interviews, games, and the general football fan gossip that populates Internet message boards. As teammates, Alonso and Gerrard had complementary styles and played well together, with a noticeable on-pitch harmony that, within the narrative conventions of football, suggested a good relationship off it as well. This was a view held not only by the fan fiction community but also by regular football fans. Interviews where either player talked about the other circulated within the community and within private blogs, appearing alongside collections of slashy images.

[3.14] In this manner, fan fiction writers eventually built up what Bacon-Smith referred to as a macroflow, the process where fans build up their understanding of the series, "creating a unified, coherent, and seemingly complete map of the series universe in the mind of the viewer" (1992, 131). The macroflow is made out of the microflow: "clusters of relational movements and constrastive actions that appear in individual episodes…and that absorb considerably more conceptual time than real viewing time" (136). The macroflow is the sense that Gerrard and Alonso have a romantic relationship, one that stretches over several years, that may or may not be finished. It is built from small moments where they hug and look delighted after a goal, when Gerrard claimed to be devastated after Alonso left for Madrid, or images of the kiss. These moments are continually discussed and debated by fans of the pairing, and slowly, as with other slash pairings, a coherent image of the relationship is created, with certain integral points. Those who enjoy the relationship eventually begin to "agree on the centrality of particular events, characteristics, and interpretations that support their favored romantic pairing" (Stein and Busse 2009, 197). "Filling Up the Space," for example, references Istanbul as one of Gerrard's key memories of Alonso, with Gerrard recalling "the way Xabi whispered to him in bed that night, his mouth pressed to the skin of Stevie's shoulder blade, Would you have still wanted to kiss me if we had lost? and Stevie said into the pillow, I want to kiss you all the time, and football's got nothing to do with it, Xabi's smile against his skin."

[3.15] What is notable about a slash interpretation of Gerrard and Alonso's relationship, however, is the relatively small amount of actual sources that fans of the pairing draw from. Unlike, for example, the constantly asserted deep bond that Kirk and Spock have for each other, the relationship of Gerrard and Alonso is built on fairly innocuous statements of admiration and friendship, pictures of goal celebrations, and, of course, the kiss. For the writers and readers, this is enough. Perhaps more than slash fan fiction built on other source texts, football slash fan fiction requires little in the way of evidence. Writers need nothing more than a picture, a quote, or an idea that two players would be good or hot together in order to write. The dynamics of football and the writers' understanding of slash fan fiction mean that that there is enough in these elements to start slashing.

[3.16] The appeal of Gerrard and Alonso as a romantic pairing is not only because of the way they interact with each other, but because of the way Gerrard and Alonso themselves are constructed within the discourse of the community. Gerrard—loyal, proudly Scouse, and somewhat rough around the edges—has his counterpart in the elegant, cosmopolitan, and occasionally intellectual Alonso. They present a classic homosocial pair, contradictory but complementary, similar to Kirk and Spock or any number of popular slash pairings. They both are considered to have not only positive qualities but also ones that are interesting to explore in fiction, including what is going on underneath Gerrard's ineloquence and Alonso's good taste in popular culture. They are appreciated as good players but also as good characters, which is what has made them so enduring in the community. Other pairings similarly reflect classic homosocial relationships, such as rivalries, mentor/mentee relationships, long-term best friends, and other varieties of complementarily contrasting characters that the community has come to understand. Indeed, the most popular players in Footballslash are the ones who feel most like personalities that can be explored.

[3.17] This understanding of Gerrard, Alonso, and any other player that is written about comes from a wide variety of sources, combined to make a coherent whole. The increased mediatization of football encourages star footballers to be considered media stars, with a focus on their personal history and personality as much as (and often more than) their sporting ability. It is not enough for a football player to be talented; he has to have an interesting personality and a certain amount of charisma—or at least be constructed to appear that way. A talented player becomes a true star by these means and can therefore build his brand and gain recognition, prestige, and lucrative sponsorship deals.

[3.18] Although this process is considered modern, it is not a particularly new development within football (Woolridge 2002). In the past, cigarette cards, newsreels, and print features focused on individual footballers with particular skill, turning them into interesting personalities that the public might pay to see perform and stars that fans would be eager to learn more about. Print was and remains a particularly key format for constructing true football stars, "those players who have more than just footballing skill, as they have a character and personality which lifts them above the ordinary star" (Woolridge 2002, 64). Profiles of star players after World War I not only discussed their skills and the history of their careers but also their backgrounds, their hobbies, who they might be as men. These stars were the draw for ticket sales and the selling of even more newspapers, just as they are today.

[3.19] What has changed is style and volume. The expansion of sports pages and an increase in football-related publications, both online and off, means that there is an increasing amount of space to be filled with content. Journalists find that "descriptive, personality-based, sports trivia is what they need most to make the kind of copy that will sell newspapers" (Sugden and Tomlinson 2007, 50), and so there is an increasingly large amount of this information available. Additionally, both football clubs and football players themselves have become content producers online, and one of the things they can offer better than the established football media outlets is personality-driven content. The official online video channels of a given football club will have, in addition to game highlights, lighthearted interviews with the team, and a player's own Web site or Twitter feed will discuss his favorite music and childhood heroes. As a result, there is a large amount of information for fan fiction writers to draw upon.

[3.20] This information is then incorporated into the discussions that members of the fan fiction community has with each other about the players and their relationships. Discussion about characters is an important element of fan communities. Bacon-Smith observed that that "in interaction with others who share in the fictional relationships, the actions and behaviors of the fictional characters generate discussion and gossip as if the characters were in some way real" (1992, 158), with Jenkins (1992, 81) also referring to this as "television gossip," seeing it as a practice of soap opera fans that was moved into the fan communities that he studied. Bacon-Smith and Jenkins see the role of this gossip as making the characters and the program more real to fans, something integral to their fan identity in that it validates the object of their fandom, making it worthy of their attentions in comparison to others.

[3.21] However, in the context of fan fiction, and especially for football slash fan fiction, this gossip also serves the opposite purpose—in making the characters real, it also makes them fictional. Through the process of gossip, fans speculate on what might happen with the characters within the narrative, whether they feel that they did right thing, or how their past may have informed their decision. They become understood by the fans, and therefore they become clear enough that the fan can write about them herself without relying on the text's official author. While a show might be created by producers, "the slash canon is based on a collective interpretive process" (Stasi 2006, 120). In real person fan fiction, without an official author and with a canon made up of many different media that must be combined, character discussion and identity creation between fans is key. Football slash writers are aware that what they are writing about is fiction, unlikely to be true, and very much in their own heads. Writers rarely try to prove their favorite pairing exists in reality, but there is discussion of who the players are and how they interact. Because this knowledge is taken from the media, it feels to the authors not much different than knowledge about fictional characters. As with other real person fiction fandoms described by Busse, the players are "simultaneously real and fictional, and…fans can talk about their fantasies as if they were real while being aware that this 'reality' merely constitutes a fandomwide conceit" (2006, 209). These character identities become something that participants in Footballslash know, can reference, and can build upon. Steven Gerrard's loyalty and Xabi Alonso's love of F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby, both part of "Filling Up the Space," are particularly important aspects of Gerrard and Alonso's characters, for example. Alonso's appreciation for literature, which he mentions in interviews, marks him as urbane and sophisticated, while Gerrard's rejection of wealthier football clubs to stay at Liverpool suggests he would show the same kind of loyalty to the people he cares about. These are both established aspects of the two men within the community. The identity that has been built, that makes them compelling characters and an interesting relationship, is therefore incorporated into the story.

[3.22] This process serves to enable the community to see football players "as fully formed, intricate, and interesting characters" (Busse 2006, 214), with an emphasis on seeing them as characters. The fans know that what they are writing about is not the real Steven Gerrard but a construction made by the community. They "purposefully use real-life information to create fictional worlds inhabited by fictional protagonists" (Busse 2006, 214). As with constructing relationships, the act of interpreting Steven Gerrard or any other football player into a fictionalized version is an extremely enjoyable activity. Fans enjoy looking through Web sites for information, discussing them with their fandom friends, and building versions of football players that they can play with. The writer comes to feel that she knows the player she is writing about, but this is different from the sort of "parasocial" (Horton and Wohl 1956) relationship where a fan feels like she has a genuine relationship with a media figure or character. Rather, the author has knowledge of her fictional creation—knowledge shared across the community, thus in one way permitting the entire community to serve as author.

[3.23] This fictionalization can also extend to the environment in which the stories take place. Fan fiction authors decide how much reality they want to incorporate in their stories. Alternative universe stories, where the players are not footballers but have some other profession, are popular. Some authors wish to stick as close to the real lives of the players as possible, dealing with the infidelity of the players in regards to their wives and girlfriends or the homophobic culture of professional football. Others bypass these less pleasurable elements while keeping the environment. "Filling Up the Space," for example, spends a good deal of time on Gerrard's relationship with his teammates, but it does not mention his celebrity wife, Alex, or suggest that they would disapprove of his relationship with Alonso. This parallels the way in which Gerrard and the rest of the Liverpool team are discussed in football media. It is often, although certainly not always, the mediated reality, rather than the absolute reality, that is the basis for football slash writers' stories, and there are many ways this can be interpreted depending on what sort of story the author wishes to tell.

4. It's just hot

[4.1] Slash fan fiction is not only about emotion, relationships, and characterization. It is also about sex, and "while it is important to note that not all slash is overtly erotic, the point is that it can be" (Tosenberger 2008, 201). While some stories are simply romantic, many are expressly, explicitly sexual. Football slash fan fiction is also a way to express and imagine sexual fantasies about football players in an environment where this is welcomed. In Footballslash, its related communities, and the personal blogs of its participants, pictures of footballers are posted with the intention of finding the players attractive—pictures of faces, shirtless torsos, thighs, and the like. The concept of the spaces of the community as dedicated to slash means that fans can "look frankly, safely, and openly at the bodies of others and…repeat that viewing experience as often as they like" (Coppa 2009, 112). Finding football players attractive in such an environment is not shameful, but rather at least half the point of being part of it.

[4.2] Whannel notes that "sport, as a social practice concerned centrally with the body, has been characterised by its striking repression of sexuality" (2002, 11). This is especially true for male athletes. The body of the male athlete, ideally, "is an instrument of supreme sporting performance rather than an invitation to libidinal pleasure" (Rowe 2004, 159–60). The body's muscles and form are created for a purpose, and that purpose is to perform, and specifically to perform for other men. Within the codes of representation of male athletes, "viewers are encouraged to concentrate on what is being done rather than on how appealing the athlete might look in doing it" (Rowe 2004, 153). Sport has long been constructed as the ideal space of and for masculinity, and "the representation of sport stars is precisely to do with the normalisation of hegemonic masculinity" (Gosling 2007, loc 4817). Within this hegemonic masculinity, "it is wrong to look lustfully at the male body" (loc 4817), and therefore the ideal way to see male athletes is with the sexual aspect removed, regardless of the intense physicality of the activity. Within this framework, it is perhaps unsurprising that "until recently, there has been a reluctance to objectify sexually the male sports body" (Rowe 2004, 154).

[4.3] As football stars become media stars, however, this has changed. In recent years, "the gradual freeing up of fixed socio-sexual identities, the influence of feminism, and the increasingly overt sexualization of culture and commercialization of sexuality have resulted in a strengthening trend of openly sexualizing sportsmen" (Rowe 2004, 154). Attractive male football players, such as Freddie Ljungberg and Cristiano Ronaldo, have been found to be effective salespeople for a range of products, especially in overtly sexualized campaigns for underwear. Male football players in states of undress sell magazines, and their attractiveness is written about as a way to entice women into paying attention to the sport. No longer is the attractiveness of football players unacknowledged, their bodies covered; rather, their handsomeness is praised and their torsos splashed across billboards. However, this recognition is set outside of regular football fan practice, positioned as something that people who aren't fans of football might be interested in and as separate from any thoughtful or serious consideration of the sport.

[4.4] Longtime male fans see a mode of fandom that acknowledges the attractiveness of the athletes as wrong, combined with an idea that women, who were rarely perceived as fans in previous decades, are new consumer fans brought in by media and marketing to civilize the game and lack the attachment to the club that authentic male supporters have (Moor 2007; Pope 2011). Interest in the narrative aspects of football and its stars, thought of as imposed by the new football media, is similarly coded as feminine and suspicious. Women are constantly asked to prove their fandom by men, and admitting to finding the players attractive is a quick way to be found illegitimate. Female football fans often "are accused that their motivation is not genuine, but is related to eroticism" (Ben-Porat 2009, 888); they have to work to dispel that notion in order to have their fandom seen as valid. This is common across football fan cultures worldwide and is internalized by female fans, who look down on those who don't follow the established masculine codes of spectatorship. In England, female fans complain about other women who "'let…us all down' by finding players attractive" (Jones 2008, 528), while in Japan, women protest that "I'm not a mi-ha fan, I'm watching soccer seriously" (Tanaka 2004, 54). The code of proper fandom "prioritizes a particular mode of spectatorship in soccer games" (54), and this mode of spectatorship is that of the heterosexual man.

[4.5] The practices of slash fandom work to overcome this contradiction by providing a space where the attractiveness of the football player is highlighted and prized that does not feel lightweight. The nature of proper fandom is inverted; eroticizing the players becomes the norm, but a norm that rewards the sort of intellectual work that goes in to writing stories or analyzing the game. As a community made up of other football fans who share the same outlook toward the players, it also allows fans to see this eroticization of football players as legitimate. There is no contradiction between being invested in Liverpool's results and being sexually attracted to Steven Gerrard within the football fan fiction community. Many Footballslash participants do not take part in any other football fan community online, preferring to reserve their comments and discussion for a place where they feel more comfortable.

[4.6] However, thanks to football fan fiction's relative secrecy, it also becomes possible to participate while still presenting elsewhere as a traditional fan. Football slash fan fiction may be relatively easy to find, but first one must know what slash fan fiction is. Football fans more generally, even those who maintain a strong online presence and identity, are unlikely to be aware of the practice unless they wish to be. Fans involved in the practice do not proselytize; indeed, there is a fairly strong taboo against making it known to those unfamiliar with fan fiction practices. Within the community itself, writers utilize user names and pseudonyms, further separating themselves from potential discovery. A different pseudonym can then be used on more mainstream football Web sites. The nature of online fandom means that it is easy to switch between the two spheres, between one form of fandom and the other. The fan fiction writer can therefore maintain her legitimacy as a serious football fan, if she so wishes, without having to give up both her attraction to players and her enjoyment of fan fiction practices. This also serves to protect the community, as mainstream football culture is notoriously homophobic and would likely react poorly to slash. The nature of online communication, with its separate spaces with separate identification that are accessed in the same physical way, means that such a division of identities is possible and that the community can be kept safe.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] Football slash fan fiction is both a result of and reaction to mediated football fandom. It exists because of the understanding of football as a narrative, but also because of what mainstream football fandom leaves out of its world. It is a way to play with the boundaries between real and fictional while also exploring the hidden potential of the football narrative and experiencing it in a welcoming environment.

[5.2] It is also a result of changes in fan fiction practice. Contemporary slash fan fiction writers see nearly any media narrative as transformable, and this potential increases when the narrative is seen as slashy. Changes in the way that fan fiction is distributed and consumed meant that the older proscriptions about what was "fic-able" and what wasn't became less powerful. Once they learn the form, slash fan fiction writers become trained to see slash and fan fiction potential in the media they encounter. Professional football's heavily homosocial environment makes it ideal for a slash interpretation, with the visual material to stimulate the imagination and a variety of potential relationship dynamics and character types to write and read about. Additionally, its similarity to cult narratives means that fan fiction writers recognize where they can fill in the narrative spaces of football to suit their needs. This is not necessarily in contrast to being a more traditional sports fan, but rather in tandem with it, a way to work through the emotions of being a football fan and to explore parts of it in a way not seen in more mainstream football fan spaces.

[5.3] Therefore, football fan fiction exists at the convergence of media narratives, media forms, and contemporary communication. It shows that the polysemy of both football and fan practice leads to new ways of understanding and appreciating one of the most enduring objects of fandom. This does not come at the expense of more traditional forms of sport fandom but rather as a complement to it, an expansion of what football can mean and how it can be interpreted.