1. Introduction

[1.1] In March 2013, social media was abuzz with news of the Veronica Mars (2004–7) Kickstarter, and each of our Twitter and Facebook feeds were filled with speculation from fans about what the movie would be about, questions from media scholars about how the Kickstarter might affect the relationship between fans and producers, and cynicism from others about what Warner Bros. might get from the film. Within just a few hours of the Kickstarter campaign being announced, blogs had been published by academics, including Jason Mittell and Mel Stanfill; industry professionals, including Richard Lawson and Joss Whedon; fans, including James Poniewozik and Willa Paskin; and of course the four of us (note 1). But what exactly did the Kickstarter entail, and why were we so interested in it?

[1.2] Launched by Rob Thomas and Kristen Bell on March 13, the project was an attempt to fund a Veronica Mars feature-length film entirely through a crowd-funding platform. Thomas (2013b), in his "Day One" message, discussed the reasons behind the project, noting, "Kristen and I met with the Warner Bros. brass, and they agreed to allow us to take this shot. They were extremely cool about it, as a matter of fact. Their reaction was, if you can show there's enough fan interest to warrant a movie, we're on board. So this is it. This is our shot." The fact that Warner Bros. had given their permission for the Kickstarter to take place added an interesting facet to the debates around crowd funding and fandom, but within 11 hours, the campaign had reached its initial $2 million goal and eventually went on to raise $5,702,153, making it, as Kickstarter noted, "an all-time highest funded Kickstarter film project." The campaign also boasts the most backers at 91,585, among other Kickstarter records that were broken.

[1.3] Smashing Kickstarter records aside, Thomas and Bell's success also brought into question for each of us the issue of fan labor. Bertha raised this question in her blog, noting that "fan agency always gets left out in arguments which purports concern that fans are being duped by studios and networks," a point Bethan took up in a post, writing, "In this case I would agree that fans are well aware that they are donating to a large studio—the difference is that it doesn't matter." Both Myles and Luke also addressed this issue of the importance of the Kickstarter, with Myles writing, "I could hear dozens of media studies professors mentally adding to their lesson plans on fan cultures," and Luke arguing that "the creation and subsequent success of the Veronica Mars Movie Kickstarter represents a troubling landmark in the emergent history of crowdfunding." The importance of the Veronica Mars Kickstarter to issues around fan labor and exploitation is thus one that stood out to each of us immediately; this thread continues to run through this piece. No longer merely acting as grassroots promoters, celebrity gatekeepers, subtitlers, and such, fans are now financing feature-length film projects on crowd-funding platforms. What are the implications of this, not just to fandom, but also to the industry? Each of us understands the issue of fan labor and exploitation in different ways, and this conversation entails both trying to understand what we mean by each of those terms and how they can be related to the Veronica Mars Kickstarter specifically and crowd funding more generally.

[1.4] In this dialogue, we gather academics and industry professionals to reflect on four issues that underpin the debates on crowd funding: fan agency, the Kickstarter platform, crowd funding itself, and finally the media entertainment industry. The dialogue took place primarily through a master document stored on Google Drive, although Twitter and e-mail were also used to share ideas and links, as press coverage, particularly on the ethics of Zach Braff's Kickstarter campaign and crowd funding, continues. Braff launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund his film Wish I Was Here in April 2013. In the introduction to the Kickstarter, Braff (2013) wrote,

[1.5] I was about to sign a typical financing deal in order to get the money to make "Wish I Was Here," my follow up to "Garden State." It would have involved making a lot of sacrifices I think would have ultimately hurt the film. I've been a backer for several projects on Kickstarter and thought the concept was fascinating and revolutionary for artists and innovators of all kinds. But I didn't imagine it could work on larger-scale projects. I was wrong.

[1.6] After I saw the incredible way "Veronica Mars" fans rallied around Kristen Bell and her show's creator Rob Thomas, I couldn't help but think (like I'm sure so many other independent filmmakers did) maybe there is a new way to finance smaller, personal films that didn't involve signing away all your artistic control.

[1.7] Much more controversy circulated around Braff's Kickstarter than the one for Veronica Mars, however, with many commentators asking whether it was ethical for Braff to use Kickstarter to fund the campaign given that he had been about to sign a deal and could afford to fund the film himself if he wanted to retain creative control. We return to Braff and the differences between his Kickstarter and that for Veronica Mars later in this conversation, and raise the issues of both antifandom of a producer/writer and the ethics of each campaign.

[1.8] The participants in this conversation are Bertha Chin, Bethan Jones, Myles McNutt, and Luke Pebler. Bertha Chin graduated with a PhD from Cardiff University; her thesis explored the notion of community boundaries and construction of the fan celebrity in cult and sci-fi television fandom. Her published work has appeared in the Journal of Science Fiction Film and Television, Social Semiotics, and Intensities as well as the edited collection Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. Bethan Jones is a PhD candidate at Aberystwyth University, researching fan fiction and gender. Her work has been published in the journals Participations, Sexualities, and Transformative Works and Cultures as well as the edited collection The Modern Vampire and Human Identity. She has recently coedited a journal special issue on the Fifty Shades of Grey series. She blogs at http://bethanvjones.wordpress.com. Myles McNutt is a PhD candidate in media and cultural studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he serves as a contributing editor and administrator for Antenna: Responses for Media and Culture (http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/). He can be reached via his personal blog, Cultural Learnings (http://cultural-learnings.com/), and on Twitter @Memles (http://twitter.com/memles). Luke Pebler is a television editor working in Hollywood, currently on the CW drama Hart of Dixie. He holds an MFA in film production from the University of Southern California and a BA in communication arts from the University of Wisconsin.

[1.9] The discussion was moderated by Bertha Chin, who blogs for On/Off Screen (http://onoffscreen.wordpress.com/) and is on Twitter as @bertha_c (https://twitter.com/bertha_c), and Bethan Jones, who can be reached on Twitter at @memories_child (http://twitter.com/memories_child).

2. Fan agency

[2.1] Q: A lot of debate has taken place around crowd funding being a form of fan exploitation. What are your thoughts on this?

[2.2] Jones: I've been thinking about this a lot lately, in part because of what something a friend of mine said on Facebook, in response to Stacey Abbott's blog post on the Kickstarter. Abbott (2013) argues that the darker side to the debate is "the potential that this is a case of the fans being financially exploited, by getting them to fund a Hollywood movie from which they will not earn any profits or even recoup their money." My friend, however, said that since the film isn't likely to come out where she lives, she's more than happy to pay the $35 to get a digital copy, plus another $15 for the DVD which she'd buy anyway. And that's something that I hadn't considered when thinking about the VM Kickstarter. I had assumed (always a dangerous thing to do) that fans would be paying to see the film in the cinema, and some of them will. But others won't, and so this gives them another way of getting to see it, as well as the DVD which they'd buy anyway. I think that a lot of the time, academics (me included), the media, and the industry forget that fans actually do have agency, and a lot of the fans being exploited rhetoric seems to come from a similar place to the fans as cultural dopes discourse. Fans can be pretty savvy—we're not all the screaming fangirls the media likes to make us out to be—and I think something like the VM Kickstarter shows that. Yes, there's a lot of emotion or feeling there, as far as the object of fandom is concerned (and here I'll admit to seeing the second X-Files film in the cinema nine times because I wanted to put as much money into the box office as I could), but there is also a line that fans won't cross. For me it was buying multiple copies of the DVD as part of the XFN campaign.

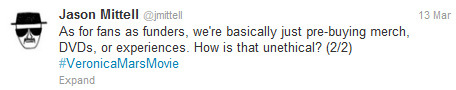

[2.3] Chin: I always cringe when the term fan exploitation is thrown around—not that I don't think it happens (Tanya Cochran's 2008 piece on Firefly fans is a good example that comes to mind), but I think Bethan made a great point there about it coming from a similar place as the fans as cultural dupes discourse. I think it's important that we don't assume fans' complete ignorance about what they're doing when they reach into their wallets and donate to the Veronica Mars Kickstarter campaign. And I'd go back to Jason Mittell's argument of this being an extension of preordering DVDs, merchandise, and/or (fan) experiences.

Figure 1. Jason Mittell's Veronica Mars tweet, March 13, 2013. [View larger image.]

[2.4] In this case, for the fans, it may not necessarily be about funding a studio film (which seems to be attracting some of the criticisms) but more about funding the creative vision of the man who brought them the beloved universe and characters of Veronica Mars (which, admittedly, was my gut reaction when I donated to the campaign). I think a more interesting question might perhaps be on fan expectations, now that fans are backers. Would fans now feel entitled to the project now that they've invested money in it? Would Rob Thomas—or any other filmmaker who received his funding via Kickstarter for that matter—now be obligated to create a piece of work that they think fans want, and would that affect forms of artistic integrity?

[2.5] McNutt: Fans are exploited every day. When they tweet about a show using a hash tag, or when they tell a friend about that show, they're completing free labor for the television network whose show they're watching. Of course, we subject ourselves to this exploitation because we've accepted that the value we get from participation—the enjoyment of social media, the satisfaction of sharing things we love with other people—is worth giving part of ourselves over to the industry. "Save our show" campaigns are an extension of this: when Chuck fans bought Subway sandwiches, or when Jericho fans purchased peanuts to send to CBS, they were protesting an industry decision by using money—and time, and energy—to reassert the series' value to their respective networks (and hopefully get more of what they love).

![Text-heavy black, white, and red poster to bring back the TV show Jericho. Main text: 'Hey...CBS! Some Very Loyal Fans Want to Tell You Something: [image of a peanut] NUTS! Bring JERICHO back for a second season! On May 16th, CBS Announced it would be Cancelling 'Jericho' for the 2007-2008 Television Season... We are NOT going to just sit by and let that happen... Signed, Millions of Viewers & BRINGJERICHOBACK.com. This ad has been paid for by the fans of Jericho on their behalf by Film.ca Inc., Oakville, ON, Canada www.film.ca and Designed by DangRabbit.com.' In a yellow box with spiky edges, text reads, 'Over 14,000 pounds of nuts shipped to CBS so far as of 5/22/07.' Text in upper right, as if on a torn piece of paper, reads, 'The Los Angeles Times: By Maria Elena Fernandez, Times Staff Writer: CBS, like the rest of the networks, announced its fall lineup last week, and the network decided to cancel 'Jericho' because the show had 'lost its engine,' CBS President of Entertainment Nina Tassler said. [paragraph break] Since then, passionate 'Jericho' fans have organized and bombarded the network with letters and e-mails that state feelings, such as 'This show has touched us like no other before' and 'CBS has cast aside a gem in Jericho.' Text in lower left, as if on a torn piece of paper, reads, 'WebProNews.com: Submitted by David A. Utter: Jake Green has inspired fans of the series Jericho to put their nuts where their passions are, and let CBS know they want the series to continue. His closing line, 'Nuts,' in the final episode, has been the impetus for a fan-driven effort to bring the show back.' Black and red text in white box, bottom left: 'Get involved & save Jericho. Find out how to contact CBS to complain. BRINGJERICHOBACK.com.' Black and red text in white box, bottom right: 'Special thanks to: NUTSONLINE.com for so staunchly supporting the campaign to save Jericho.'](https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/download/519/version/821/423/4345/figure-2.jpg)

Figure 2. Bring Jericho Back campaign poster. [View larger image.]

[2.6] The Veronica Mars Kickstarter is certainly an evolution of this principle, asking fans to do more than send Mars bars—which, to their credit, they had to import from other countries—to the CW and instead "funding" production, but the way the Kickstarter was framed very much placed this into the context of fan activism: the logic was not that Rob Thomas and Kristen Bell needed fans' money to make this movie, it was that they needed their money as a symbol of their fandom which would convince Warner Bros. the movie was viable. And so while the end result of the campaign was fans funding the production of the Veronica Mars movie, Thomas and Bell's rhetorical pitch to fans was comfortably within the logics under which they had previously engaged—and on some level continued to engage, after cancellation—with the show; combined with the existence of tangible goods being exchanged for their pledges, I find it hard to consider this exploitative of fans (or, rather, I find it hard to differentiate this form of exploitation from the daily exploitation that we've commonly understood as part of television culture).

[2.7] Pebler: Of the four of us, I have probably been the most critical of the VM Kickstarter up to this point. All your points are well taken: fans are, by and large, a smart and actualized group. They wield real power, they've got good bullshit detectors, and they're not generally in need of protection from the evil content producers. And, yes, you can broadly view almost all fan activity (online evangelism, auxiliary product consumption, etc.) as exploitation that is weighed against the enjoyment fans derive from their participation. But this is different. Traditional preordering is one thing, but this amounts to an auction wherein Warner Bros. effectively gets to set prices based on the intensity of each individual fan's devotion. Instead of maximizing revenue by courting more customers at fixed prices, which is the way things normally work, they get to maximize on a per-fan basis. Even better, they can bid up their customers with soft talk of not only the reward premiums but the actual product. The more vague they are about the tees and posters and the very movie itself, the more people will imagine the best and be willing to pay! The fact that Kickstarter allows unlimited funding beyond the initial goal is, to me, a huge problem. It's a loophole that makes this sort of exploitation possible. Bethan, your friend may be happy to pay $35 for a digital copy of 90 minutes of Veronica Mars (marginal cost to producer = $0), but that doesn't make it right for Warner Bros. to ask her for it. I'll be getting the same movie, likely on the same release day, for no more than $5 or $6 at Amazon or iTunes. Fans' devotion to the series was used as leverage to get them to massively overpay for goods they won't see for a year, at least. That is absolutely exploitation, as far as I'm concerned.

[2.8] Jones: Does the VM Kickstarter become more about a question of ethics than exploitation, then, in that it's unethical for corporations like Warner Bros. to exploit both loopholes in the system and fannish attachment to a text in order to profit from it? If so, I think that's an interesting shift from the way that fan exploitation has typically been analyzed (fans as dupes rather than corporations as unethical). As Bertha and Myles have noted, fans aren't ignorant of what they're doing when they put money into a Kickstarter or use official hash tags, and fandom can be extremely vocal about and critical of texts. I'm sure there are VM fans who won't have contributed to this Kickstarter because of issues around how it's been framed, Warner Bros.' involvement, or a variety of other reasons. I think that, on the whole, if fans think they are being exploited, they will make their feelings known. I do think there are issues with the VM Kickstarter (i.e., fans are funding a studio film), and I can see your point, Luke, about Warner Bros.' actions, but I think Bertha's point about the fan experience is an important one (Myles also wrote about the Kickstarter as a social experience, which I think is useful in thinking about the fan experience). By contributing to the VM Kickstarter, fans don't simply get a script, T-shirt, copy of the DVD, etc.; they become part of the success of the project. That affords them cultural capital within fandom (though of course, the more they contribute, the more capital they accrue, which I do think has interesting repercussions for hierarchies in fandom and the amount that gets contributed to the Kickstarter), at the same time as consolidating a feeling of community between fans who have contributed. I don't think that can be ignored when we talk about things like exploitation. I also wonder whether we need to take fan voices into account more in these discussions. If we're having fans telling us no, they don't feel exploited, is there value in us as academics and industry professionals telling them that actually, they are? Do things like the VM Kickstarter mean that we need to reevaluate how we study fandom and the language that we use?

Figure 3. "I saved Veronica Mars on Kickstarter" sticker, one of the stickers offered as a reward for backers pledging $10 or more. [View larger image.]

[2.9] McNutt: Connecting two of your points, Bethan, is there a risk of reinforcing fans as dupes if we insist on their exploitation despite their insistence they are willing participants? It's slippery territory, although I would generally resist telling fans anything—rather, I think anything I write about fans or fandom which is then consumed by fans is designed as the start of a conversation rather than an intervention. I don't know if we have to reevaluate how we study fandom, but I do think this is an area where our understanding of its exploitative qualities might need to wait until discussions like this one have taken place within fandom. Even just a few months later, we're still in the glow of the Kickstarter's success, and a lot of this will come down to how the Veronica Mars fan community participates in this process over the course of the next year or so.

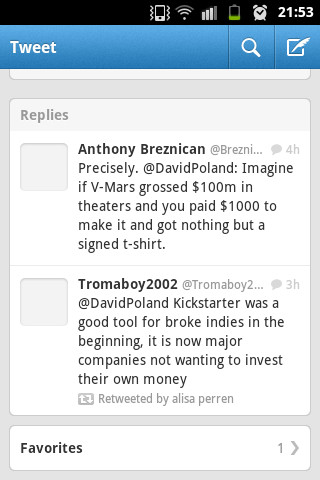

[2.10] Pebler: You're probably right, Myles, that we're in a rose-tinted honeymoon period. Perhaps it will self-correct; certainly the success of future campaigns will be contingent on (fans' judgment of) the results of today's. That said, it's often voices from outside the community that spark subsequent debate within it. Starting the conversation is a worthy pursuit, as you say. In that spirit, I think it's important to point out that there are other creators exploring alternative models for continuing their stories and distributing content direct to fans—ones that eschew leveraging their fame through crowd funding. Look at Joss Whedon's Buffy season 8 comic or Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog Web series, or Brian K. Vaughn's new Web-optimized comic The Private Eye (http://panelsyndicate.com/).

Figure 4. The Private Eye issue 1 cover. [View larger image.]

[2.11] Vaughn refers to crowd funding in the afterword of issue 1: "[Private Eye artist] Marcos and I really like sites like Kickstarter, but as relatively old hands in this biz, we didn't want to shake the tin cup until we had a finished product to share." Fans are encouraged to "name your price": casual readers can try the work for free, while those that crave the experience of helping to support future issues can do so to any degree they desire. Granted, it costs more up-front money to make a movie than an online comic, but if the ultimate goal is continuing a story that fans love, by hook or by crook, with less meddlesome suits in the middle, then these methods achieve that goal without placing an unethical financial burden upon the consumer. I think that's to be applauded.

[2.12] Chin: I do wonder if those rose-tinted honeymoon period is starting to fade, though, with the recent backlash against Zach Braff's Kickstarter campaign (Gadino 2013). Or is this a case where, in terms of Hollywood hierarchy, Rob Thomas is seen as the underdog whereas Zach Braff isn't? Luke, your mention of Brian K. Vaughn's name as your price model reminded me of a similar thing the British band, Radiohead, did with their 2007 independently released album. Interestingly enough, Radiohead's front man, Thom Yorke, recently spoke of how much he regretted going down that route, suggesting that their experiment with the model actually helped companies like Apple and Google devalue music (Sandoval 2013). Although music is a wholly different industry, I wonder if the same thing would eventually happen with other creative industries. Bethan's point about ethics is also an important conversation to have, I think, and Kickstarter's unlimited funding beyond the initial goal, which Luke highlighted, can be argued as an ethical issue as well, particularly for campaigns like VM's and Braff's. But it becomes a complicated issue, as the unlimited funding would certainly allow creators without any industry connection to put more into their project.

[2.13] In terms of reevaluating how we study fandom, or at least reconsider the language and terminology that we use, I think this is something that is already happening. In terms of thinking where the study of fandom began, from justifying the cause of active audiences to the current work on fan activism and fans turned producers, fan-ancing, to borrow the term from Suzanne Scott (2013), is likely going to be the next step, especially seeing as we're already having this conversation right now.

3. Kickstarter (as a platform)

[3.1] Q: What are the benefits and/or drawbacks to the crowd funding model offered by Kickstarter and other sites like it?

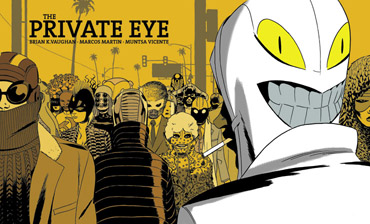

[3.2] Jones: One interesting thing I've found now is almost a backlash against Kickstarter. I noticed a conversation someone had retweeted into my timeline the other day which illustrates this really well, and it does seem to be the case that the more well known projects on Kickstarter are the ones where there are big names attached (VM, Amanda Palmer, etc.).

Figure 5. Twitter conversation about Kickstarter being overtaken by celebrities. [View larger image.]

[3.3] I wonder whether this will cause problems either for Kickstarter or for the indie projects that want to use it. Is it likely that indie projects will get sidelined and not raise the money they need? Or will Kickstarter start changing the way they run in order to make more of a profit from the larger names?

[3.4] Chin: I actually got to know about sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo via friends who are indie filmmakers, so I've donated to quite a few of these myself. It's certainly a great platform for indie filmmakers, for people who are making short films and Web series to get their material seen as long as they manage to get it funded. It also allows them to work outside of the studio system. Having said that, I've seen how fulfilling perks to backers have taken its toll: if you're already strapped for cash for a project, imagine having to spend even more on printing T-shirts, DVDs, and shipping. I often wonder how much of the money I donated actually went into the production costs instead of delivering the perks. There's also the issue of accountability: what happens when perks aren't delivered on time? Or if things change and you lose an actor you've cast but fans have already donated money?

[3.5] McNutt: There's no definitive answer to this question, which is itself both a benefit and a drawback to Kickstarter and other sites. For every indie developer whose video game gets a new lease on life through fan support and online promotion, someone like Zach Braff—successfully (http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1869987317/wish-i-was-here-1)—or Melissa Joan Hart—unsuccessfully (http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/318676760/darcis-walk-of-shame)—uses his or her celebrity to help fund passion projects, and in the process our perception of crowd funding is shaped and reshaped. The Veronica Mars Kickstarter was received as a triumph of audiences—which is not to say that Luke and others haven't expressed their reservations, but rather that the press around the project has been largely positive—while Braff's effort to retain final cut on his follow-up to Garden State was considered a bastardization, even though one could argue that Braff's desire to maintain his independence from the demands of studio financiers is actually closer to the spirit of Kickstarter than Veronica Mars' Warner Bros. production account. The uncertainty of Kickstarter's value allows a project like Veronica Mars to emerge and catch the Internet by storm, but the same uncertainty of value could lead to other worthy projects—projects that lack the same promotional push—going unfunded as the site is flooded with projects that shift the value of crowd funding in different directions. The free-for-all nature of the site enables huge success stories, for content creators to redefine value to their benefit, but it also makes it impossible to pin down a consistent logic of crowd funding on the platform (or on any platform).

[3.6] Pebler: I agree with Myles—Kickstarter is a platform, and its rise to prominence is at least partially due to its flexibility. It's able to serve the needs of a variety of users, large and small. I doubt that backlash against high-profile campaigns will somehow soil the platform and negatively affect the ability of smaller projects to find funding because campaigns are generally promoted through separate channels controlled by the artists themselves (social media, personal Web sites, word of mouth). Bethan, your idea of KS trying to use big projects to generate revenue is a really interesting one. It's a sort of progressive tax, where the bigger the project total, the bigger the Kickstarter share gets, while the smallest projects have their fees waived. It could be a way to make the system a little more self-regulating and even the playing field. You'd have the Amanda Palmers and Zach Braffs of the world indirectly subsidizing the tiny projects. Matt Honan's 2013 article in Wired posits a future of proliferating crowd-funding sites geared toward specific niches, and I think he's right on. If Kickstarter does turn off part of their user base by deciding to somehow cater to large, high-profile projects, surely another site will pop up as the place for true independents, and so on, as is the circle of life in the age of software and social networks. As crowd funding matures, it will likely stratify in order to court different user bases, just as social media and fandom itself have.

[3.7] Jones: I think the points you make, Bertha, about production costs versus the cost of perks and accountability are really important ones. I'd be interested in seeing a full breakdown of the costs of a crowd-funded project to look at how much time and money is spent on the promotion (including the perks) and the actual production. If it's the former, is Kickstarter better seen as a means to promote and publicize a project rather than raising money to fund it? I also think the question you raised earlier about fan expectations is relevant in relation to accountability. I know Rob Thomas said in an interview with Hitfix that he had to seriously consider what kind of film he wanted to make:

[3.8] There was a real internal debate, for me, about what kind of movie I wanted to make. Just by way of example, I really enjoyed "Side Effects," and that sort of noir thriller that I could see Kristen Bell as Veronica Mars in something like that. I liked the plotting of that movie. I had some desire, as a filmmaker, to take Veronica in a slightly new direction and do something adventurous with her. Or, there's the "give the people what they want" version. And I think partly because it's crowd-sourced, I'm going with the "give the people what they want" version. It's going to be Veronica being Veronica, and the characters you know and love…but it was a creative debate I had with myself, and I finally made the decision that I'm happy with it, to go with, "Let's not piss people off who all donated. Let's give them the stuff that I think that they want in the movie." (Sepinwall 2013)

[3.9] Here, at least, there seems to be some element of accountability toward fans, but how much will this impact upon the story being told in the film? How will Thomas giving people what they want affect future big-name Kickstarters? Will it actually have any effect?

[3.10] Also thinking about what you said about value, Myles, how are we defining value in relation to Kickstarter and crowd funding? Who determines what is worthy and what isn't? And is this another case where we need to look at the terms we're using and whether they're relevant to what we're actually discussing?

[3.11] McNutt: Value is a huge question, one that obviously we don't have room to answer here, but your example raises a good point: does Rob Thomas still get to define the value of his own projects when he's accountable to tens of thousands of backers? However, I would argue that by creating a Kickstarter built on nostalgia (the video featuring the previous actors), and by choosing to directly appeal to fans, Thomas was very clearly accepting of fan-determined value from the moment the campaign began.

Video 1. Veronica Mars Kickstarter video.

[3.12] I'd actually argue, though, that this gives him greater space in which to define value, in that he is allowing fans an opportunity to guide broad discussions of value in order to allow him some wiggle room. As Thomas has spoken of Veronica's romantic entanglements and returning cast members, he has been very careful to speak around certainties in favor of a promise that it will be true to the series, something that fans can trust knowing that the project as a whole is positioned as "more of what they love." Any continuation of a canceled TV series would have to handle this balance in the same way, whereas I think original big-name Kickstarter projects are possible provided they are up front about how much value backers have within the creative process. Thomas used his appeal to fans as a way to encourage them to participate, ensuring them their participation was already being valued as he wrote the film, which I think is a big part of the Kickstarter's success as it relates to cultural capital; not every project could do the same, but the definition of value remains open for interpretation within the platform.

[3.13] Chin: I agree with Myles that the definition of value is open for interpretation. Thomas pitched the campaign as a continuation of the VM universe, and his updates to backers have been quite detailed thus far, with promises of more. In his last update, for example, he wrote: "We want to find new and better ways to keep you involved. We want you to feel like you're part of the process. And while we don't want to spoil the fun of the movie, we do want you to see as much as you can." Just as backing Braff's project is about ensuring that the filmmaker has full artistic control of the project, as he detailed in his project's rationale: "I want you to be my financiers and my audience so I can make a movie for you with no compromises."

[3.14] I think it'll be interesting to see—perhaps after the final cut of the VM film has been released—how accountability fits into the conversation, particularly among fans, which brings this back to my earlier point about fan expectations, especially now that they have a financial stake in it. I know of one other Kickstarter project that may have lost one of its main cast, and whose fund-raising pitch was rather dependent on the casting of the actor. Nothing has been officially announced by the filmmakers on this change as yet, so it remains to be seen how, and if (or when), accountability—and fan expectations—comes into the picture when that happens.

[3.15] Pebler: A recurrent theme in these discussions seems to be, how will it all look once it's over and the thing kickstarted is complete and released? Will backers ultimately be happy? Will producers be happy? Will it all have been worth it? It's going to be an excruciatingly long wait to find out, in many cases. There seems reason to be bullish on the future of crowd funding in general, though. Kickstarter's official response (Chen, Strickler, and Adler 2013) to the VM/Braff backlash is, "Look how many people join as a result of these headline grabbers and end up giving to lots of other smaller projects as well!" And I think that's great news, if it proves to be true in the long run. Perhaps, regardless of ethical implications or quality of final products, the big names are to be tolerated because of the halo effect they generate.

4. Crowd funding

[4.1] Q: Crowd funding isn't a new phenomenon, so why do you think it has become so successful and widely known in the last couple of years?

[4.2] Jones: I'm going to say that social media has played a big part in this. I certainly heard about Kickstarter through Twitter (more so than Facebook), and it being used and promoted by big names (Neil Gaiman, for one) means that a lot of Kickstarter projects pop up on my feed regularly. It's a quick and easy way of getting information about projects out there to a lot of people, and that makes a big difference, I think.

[4.3] Chin: I think the VM project certainly propelled the concept to the mainstream consciousness. But as I understand, it's been common in the music and games industry. The success of Joss Whedon's Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog very likely made people aware that it's possible to make a creative piece of work without the backing of a studio, but because not everyone is Joss Whedon, the existence of crowd funding seems like the next best (practical) thing. Furthermore, we're in a climate where user-generated content and the idea of the collective intelligence and crowd sourcing are becoming increasingly recognized and cultivated.

[4.4] McNutt: In the case of the media industries, one of the factors has been how new forms of distribution have made the logics of crowd funding much easier. Within the video game industry, new platforms like Apple's App Store, Valve's Steam, or even the major console maker's respective digital distribution setups have all given small independent developers the ability to reach wide audiences without the need of a large publisher and physical distribution. Similarly, the rise of the Web series Video Game High School (http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/freddiew/video-game-high-school-season-two?ref=live), which was, before Veronica Mars, the highest-earning film/video Kickstarter, has created a new space for content creators where they can turn to crowd funding to make something they can then release on their own terms without the need for networks or studios. The Veronica Mars Kickstarter is perhaps outside of this development, given that the film will be distributed through traditional means, but I think the larger move toward crowd funding has been the result of nontraditional ways of delivering content to audiences who lend themselves to nontraditional ways of funding that content.

[4.5] Pebler: I see crowd funding's rise in profile as a natural side effect of technological progress and the maturation of online culture. You've got more people with more connected devices, more comfortable with technology, and invested in online communities. The customer base is increasingly receptive to a media landscape that includes nontraditional content sources consumed in a myriad of ways. Meanwhile, artists seeking patronage are as old as art itself. As people increasingly live their lives online, it's only natural that they start to look for seed funding online as well. Kickstarter, on its surface, represents a way for fans and creators to get closer together, cutting out the corporate middlemen, so it's no wonder that it's become a great white hope for fans of media properties cut down before their time. The trick will be to wrest the underlying intellectual property of these shows from the giants that own them. Otherwise any appearance of independence will be an illusion, as it is with Veronica Mars.

[4.6] Jones: Reading your responses made me think of the way that Amazon is making self-publishing much easier. Although it's not crowd funding, it certainly comes under the umbrella of nontraditional ways of delivering content as well as technological progress. Crowd funding does seem to be a more acceptable way for getting your film, Web series, or game out there than self-publishing is. Whether that's to do with the history of traditional publishing and the idea of what literary work is I'm not sure, but do you think crowd funding will make other areas of nontraditional content delivery more acceptable?

[4.7] McNutt: While it might make them more acceptable, it doesn't make them easier. The logistics of crowd funding—as noted above—are a challenge, such that anyone who could secure solid terms on more traditional capital is likely to take that opportunity. It's similar to self-publishing in that way: if you could get reasonable terms with a real publisher, you would probably take that deal. There have been a number of video game kickstarters that have backed out of crowd funding after their campaigns brought investments from traditional sources, which removes the burden of fulfilling rewards and the like. As a result, while nontraditional content delivery is absolutely part of what makes crowd funding possible and in many cases desirable, the legitimacy and efficiency afforded by traditional publishing continue to hold value.

[4.8] Chin: Myles definitely made a great point there. The symbolic capital attached to traditional content delivery still holds great value. That's not to say that nontraditional content delivery isn't equally important. I think in terms of your comparison to the self-publishing industry, Bethan, perhaps the difference is that films, games, and music are often a collaborative effort compared to a self-published book, whereby it's easier to be accused of vanity publishing.

[4.9] Pebler: You've hit upon another reason it's difficult to make generalizations about crowd funding, Bertha: the huge variety of projects it's being used for, and the accordingly wide range of collaborative and capital needs of those projects. Production costs of different mediums don't always correlate nicely with the relative fame/support level of the artist Kickstarting. This leads to situations such as Amanda Palmer raising $1.2 million—12 times her goal—to produce a record, and being subjected to (presumably) more scrutiny than if she'd only raised what she initially set out to. Again, the uncapped nature of Kickstarter could be considered a boon or an albatross, depending on how things play out. With increased funding comes increased accountability and increased exposure to criticism. The media properties we currently enjoy are products of the industrial systems that produce them; it will be interesting to see if a change in the nature of funding precipitates any change in the content itself.

5. (Media/entertainment) industry

[5.1] Q: Are crowd-funded projects really likely to change the entertainment industry?

[5.2] Jones: They already are, aren't they? We're having a dialogue about a VM Kickstarter that raised close to $6 million—that's a big change, and I think regardless of what happens next, the industry is going to have to adapt in some form.

[5.3] Chin: It probably is, but I don't think they're big changes that we can see right away—it is enough for us to be having this particular dialogue right now though. But I also think VM happened because all the industry players agreed to it, chief of which is Warner Bros., which may not necessarily be the case for other fan favorites out there—Bryan Fuller said a Pushing Daisies film will need at least a $10 million budget, and X-Files fans who immediately asked former executive producer Frank Spotnitz about the possibility was told that it isn't likely going to happen (note 2). More importantly, I think the big studios would want to look at ways of taking opportunities with this which probably culminate in the criticism that Kickstarter has come under lately, for being a playing field of the big boys now instead of the darling of the independents.

[5.4] McNutt: More broadly, the answer is no: crowd funding will still represent a small percentage of projects within the entertainment industry, high-profile examples of crowd funding like Veronica Mars still depend on the industry for distribution/promotion, and there remain enough concerns over the logistics and ethics of Kickstarter and other crowd-funding platforms that any sort of wide-scale implementation would be both ill advised and ill received. However, I do think it changes how we conceptualize value and how we understand the audience's place within film and television production, prompting new questions we'll pose to students when considering concepts like Derek Johnson's (2013) notion of co-creativity; at the same time, however, the industry has always worked to subsume audience labor and audience contributions within its preexisting logics, and the Veronica Mars Kickstarter—while empowering on a surface level—represents a case where the industry isn't being threatened by crowd funding so much as they are evolving to work crowd funding into their existing logics. That's a change, certainly, but not a substantial one (at least not yet).

[5.5] Pebler: If you define the entertainment industry as large, established players, then probably not—certainly not in the short term. At its core, crowd funding is about just that—money—and the studios don't lack start-up capital. Being too cash strapped to produce content is not a problem they have. Also, keep in mind that the people who raise millions on Kickstarter can do that because they already have mainstream media identities. Without the fertile loam of Hollywood shows and movies and music, there'd be no one famous enough to reap giant crowd-funding harvests. I've thought about it a lot, and I'm still not quite sure what Warner Bros. is hoping to gain by letting Rob Thomas crowd fund VM. It may be simply good press, which they (briefly) got. But I predict it's going to be a long, strange road for them to get this movie out, with too much accountability to the legion of people whose money they accepted. I doubt that they'll think that a paltry $5.7 million was worth it, in retrospect. That said, social media has put content producers in close proximity with their audiences. Continued evolution of that relationship is inevitable, and potentially a great thing. I've often wondered whether TV networks might find a way to start showing pilots to the public before they decide which ones to pick up for broadcast. (Challengers like Amazon are doing it already; see Thomas 2013a.) Instead of jilted fans coming together after a show has been canceled to beg or bribe the network to bring it back, we might have viewers' voices helping decide what goes on the air in the first place.

[5.6] Jones: I realize I should have been more clear on the terms I was using! I'm thinking about the entertainment industry in its broadest conception, so not just the large, established players like Warner Bros., but indie producers, fans, and to an extent the academy which studies fans and audiences. I do think that for the latter, crowd-funded projects will change the way we study audiences and how we conceptualize the terms we use, as Myles said. I think you're right, Luke, in saying Warner Bros. have a long and strange road ahead of them, and it will be interesting to see how that develops and whether any other studios decide to follow in their footsteps.

[5.7] McNutt: I also think that a lot of this depends on a sort of self-regulation: as I write this, a new video game crowd-funding experiment by Precursor Games—for a new game called Shadow of the Eternals (http://www.precursorgames.com/)—is using a self-made platform with its own terms of use, which stipulate that "a donation cannot be canceled or returned once it has been completed, whether or not Precursor Games completes the Game or fulfils the specified reward." Online users criticized this legalese, forcing one of the developers to reiterate that they would, in fact, refund any donations should the game not be completed, but it created controversy around the project that could threaten its reputation (as the terms of use are far more legally binding than a FAQ page). I definitely agree that Warner Bros.' experience will be watched very closely by other studios before making a move—we're not the only ones watching this situation closely, and we're not the only ones who are working to conceptualize its uncertain impact on the industry.