1. Introduction

[1.1] The Internet is bridging different forms of storytelling media and their communities, meaning that to some extent, everything is becoming a transmedia narrative. This shift is opening new opportunities for scholarship even as it destabilizes the dividing lines between previously distinct forms of media. If a significant proportion of fan engagement with television shows, comics, films, video games, and other forms of popular culture are all playing out online alongside texts like alternate reality games (ARGs) that exist entirely in that context, where do we draw the lines between them?

[1.2] What makes each kind of textual storytelling distinctive is not found at the level of textual structures but at how we engage with them. The process each medium requires of us in order to negotiate a given text helps shape the way we perceive the story and different modes of engagement alter our experience of texts (Veale 2011, 2012b). As such, I have argued elsewhere that media forms should be defined by the processes of engagement required of their textual structures and the affective responses shaped by that engagement as much as by their textual structures in isolation (Veale 2012a). The simplest example of this is to compare watching a film in the context of a cinema to watching it at home on DVD: in the cinema, no matter how tense a scene might be, everyone knows that the film will not stop and is outside our control; in comparison, when watching at home, it's possible to pause the film to make a cup of tea if it becomes too tense in order to take a breather. The same filmic text exists on two different textual structures, which promote different modes of engagement and very different affective experiences as a result.

[1.3] ARGs are defined by processes of engagement rather than textual structure because they can be constituted by any form of textual engagement common to the Internet at large; the only boundary demarking where an ARG ends and reading e-mail for work begins exists at the level of affect (Veale 2012a). At the same time, modern television is demonstrating some slippage into modes of engagement and resulting affective tenor often associated with ARGs:

[1.4] Technological transformations away from the television screen have also impacted television narrative. The Internet's ubiquity has enabled fans to embrace a "collective intelligence" for information, interpretations, and discussions of complex narratives that invite participatory engagement—and in instances such as Babylon 5 or Veronica Mars, creators join in the discussions and use these forums as feedback mechanisms to test for comprehension and pleasures. Other digital technologies like videogames, blogs, online role-playing sites, and fan websites have offered realms that enable viewers to extend their participation in these rich storyworlds beyond the one-way flow of traditional television viewing…The consumer and creative practices of fan culture that cultural studies scholars embraced as subcultural phenomena in the 1990s have become more widely distributed and participated in with the distribution means of the Internet, making active audience behavior even more of a mainstream practice. (Mittell 2006, 31–32)

[1.5] Modern television is increasingly framed around online communities forming collective intelligences through which to negotiate complex texts, and there is thus a significant experiential overlap between playing an ARG and engaging with the communities that surround television shows. Approaching media forms on the basis of their modes of engagement and how those modes of engagement shape the affective experiences they mediate rather than their outward distinctions provides an opportunity for critical insight that might otherwise have been missed. Doing so means that tools from modern television scholarship can be deployed to consider elements of ARG communities at the same time as theory developed in the context of ARGs can be focused on television fans. This allows for a more unified overall perspective regarding how fan communities and the economies that surround them function, how engaging with fan communities changes the experience of texts in fundamental ways, and how television shows are moving to reflect their audiences and engage them in dialogue.

[1.6] The concept of using the lens provided by ARG engagement to explore broader media is not new: Paul Booth (2010) has argued that modern fandoms across media qualify as ARGs due to online convergence and a "philosophy of playfulness" (2):

[1.7] Fans are actively engaged in their media texts, participating in some way with the creation of meanings from extant media events. Players of ARGs, similarly, participate in the active reconstruction of the game environment, and create new meanings from the intersection and convergence of media texts. Further, active fans who create fan fiction regularly transgress the boundaries of the original text, by adding new material, creating new readings, or providing alternate takes of the plot of the original. Similarly, ARGs utilize ubiquitous web and digital technology to help players participate in a game that is both constructed through and effaced by mediation, transgressing and destabilizing traditional media theories. In short, the types of participation in which fans engage minors the type of participation in which players of ARGs engage; and this type of participation is reflected by many contemporary media audiences in general. (2)

[1.8] Booth's argument that the kinds of engagement presented by modern media fandoms map onto that of an ARG is persuasive, and his work presents useful tools for understanding the flow of capital within fan communities. However, his argument can be extended further because he does not consider the affective dimension to the experiences under comparison. The affective dimension of something refers to a spectrum of subjective things that we feel but that we are less conscious of than our emotions. It is possible to name an emotion and pin it down, but the affective tone of an experience is harder to label and is more amorphous (Kavka 2008). A good distinction is that between fear and dread: fear has a distinct focus, whereas dread can lack a focus or even a conscious reason for us to feel the way we do. Affective investment is contextual (note 1) (Nyre 2007) and reflects whatever is relevant to the individual engaging with a given text and his or her situation at the time. The affective tone of those watching something they enjoy changes when they watch the same thing in the context of studying it (Veale 2012a).

[1.9] In contrast, Matt Hills engages with affect in Fan Cultures, arguing that fans should be viewed as players becase they become "immersed in non-competitive and affective play" that is "not always caught up in a pre-established 'boundedness' or set of cultural boundaries, but may instead imaginatively create its own set of boundaries" (2002, 112). However, Hills misses some of the internal dynamics within fan communities that map to ARGs, such as the fact that some of the affective play is entirely competitive, along with the affective impact of cocreative engagement between the creators and the fan community in shaping unfinished texts.

[1.10] Exploring the experience of community engagement centered around the television series My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic (MLP:FIM) (2010–) will illustrate how the modes of engagement involved overlap with those of ARGs. MLP:FIM displays the rabbit holes common to ARG experience at the levels of both the text and its paratext (Genette 1997). There is direct engagement between the creators of the show and the community in a relationship analogous to how ARG communities relate to the people who guide the game. Contributions at the level of the MLP:FIM community become folded back into the official text, suggesting a cocreative engagement. The fan community displays the same experientially distinct tiers of engagement as ARGs do, with similarly distinct modes of engaging with cultural capital.

2. Rabbit holes, both textual and paratextual

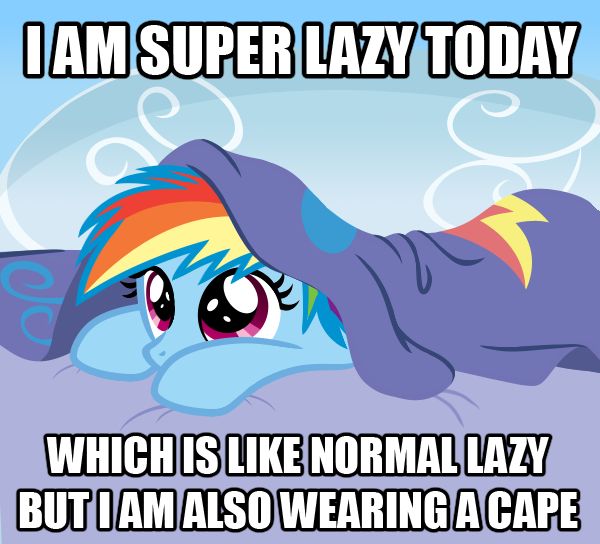

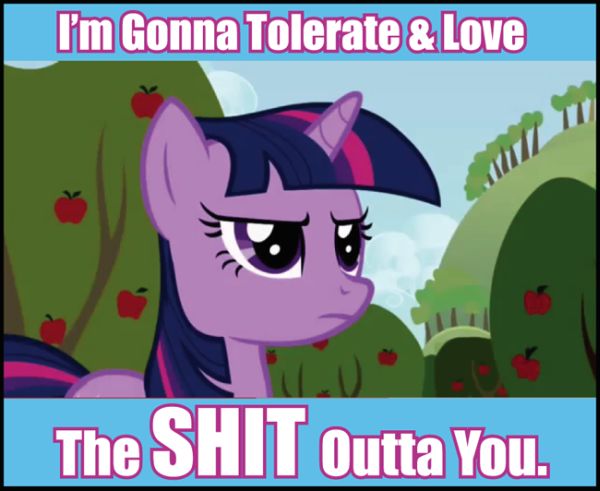

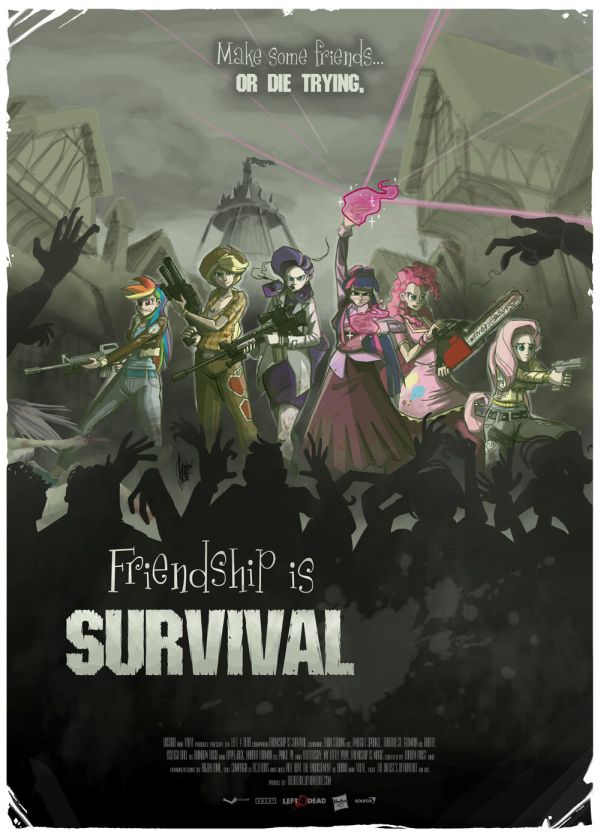

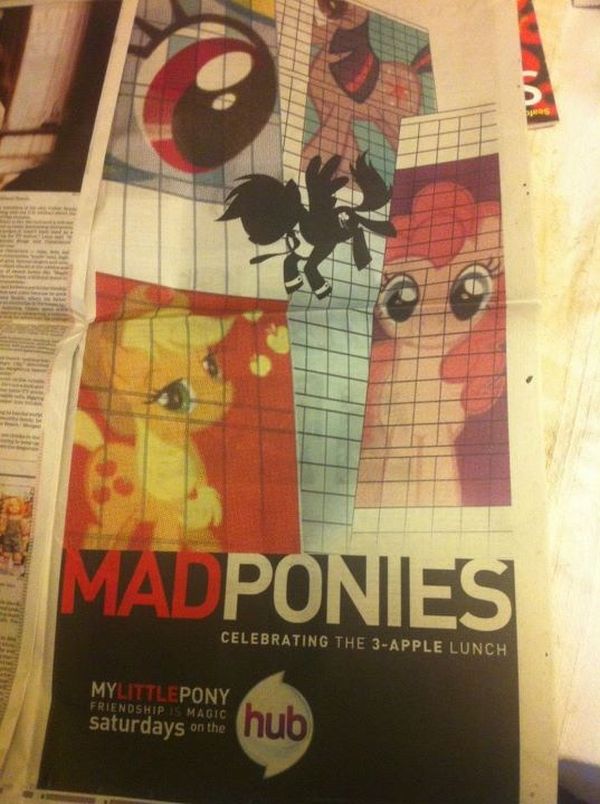

[2.1] The television show MLP:FIM has developed such a ubiquitous online presence that it has been hard to avoid encountering it within many virtual communities, whether they are dedicated to a form of fandom or not. One consequence has been that the first encounter many people have with MLP:FIM is through online image memes, posters, or discussions rather than through dedicated advertising or watching the show itself. As a result, these encounters with the show's paratext shape the first impressions that many people have of MLP:FIM as a series; for example, the difference in tone and context between official advertising (figure 1) and the community-generated images (figures 2–4) is hard to miss. Another important element about the comedic images is that they imply a community of other people who might share a similar sense of humor with you as the reader—and that they are enjoying engaging with MLP:FIM itself. Figure 4 borrows the same context as the advertising image (figure 1) in that it presents the core characters in ways that make them distinctive, except it does so through the medium of parodying a video game poster of Left 4 Dead (Turtle Rock Studios, 2008) that has the characters working together to fight zombies (TheArtrix 2011). The shift in context brings MLP:FIM closer to themes enjoyed by an older, and in this case primarily male, audience, and it does so with visual style in such a way that the labor involved is obvious. The encounter raises the question, "What is this show that people are spending so much time and energy on, when they're connecting it to other things I already enjoy?"

[2.2] Community is a feeling, not just a process (Rheingold 1993). Participating in a wider group that shares at least some of the same interests and purposes is itself a powerful thing. Encountering and enjoying these images provides a connection to a visible community of other people who share a similar sense of humor and engagement (note 2). That remains true even for those who may not have actually watched any of the series that inspired the paratext. The creators of MLP:FIM are aware of the ways that fandom communities are engaging with their show, and they have folded the same style of humor into their advertising: figures 5, 6, and 7 all show the same kind of playful self-awareness and engagement with popular culture that the community has delighted in (note 3). The cumulative effect of all of these minor encounters is to build an impression that a community of people are having fun that is centered around a particular television series, and that the creators of the show are playing with and alongside them.

[2.3] In the context of discussing ARGs, rabbit holes refer to entry points into the text—ones where questions are raised that some people will be motivated to investigate (Szulborski 2005a, 2005b). The advertisements in figures 5, 6, and 7 are explicitly grounded in being this kind of locus for curiosity: only one of them mentions which day of the week episodes of the series are broadcast, with the others only mentioning the channel. Those who want more information need to start hunting for it themselves. Any of the paratextual material produced by the fan community or the creators themselves can function as a rabbit hole for MLP:FIM, and the order in which material is encountered is going to help shape the affective impressions that people take into the series with them (Veale 2012a). The mode of engagement they present is affectively identical to that of ARGs.

Figure 1. Advertising. [View larger image.]

Figure 2. Super lazy. [View larger image.]

Figure 3. Love and tolerance. [View larger image.]

[2.4] Figures 2 and 3, which are sight gags, have been recirculated to the point that attribution is practically impossible; all make use of a similar sense of humor that meshes and juxtaposes with the imagery for its impact. They're also used as a comedic visual shorthand during online communication, standing in for written statements.

Figure 4. Friendship Is Survival (TheArtrix 2011). [View larger image.]

Figure 5. Bridlemaids ad. [View larger image.]

Figure 6. Ponygeist ad. [View larger image.]

Figure 7. Mad Ponies ad. [View larger image.]

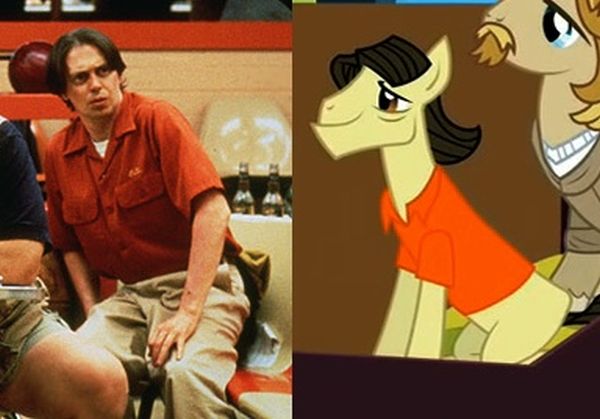

[2.5] However, the show itself also features elements that can qualify as Easter eggs and intratextual jokes or as rabbit holes, with the sole difference being the mode of engagement of the person viewing them rather than anything intrinsic to the texts themselves. These go beyond the kind of content that would make sense for a children's demographic and are grounded in a deep engagement with popular culture. For example, 2.06 "The Cutie Pox" features background characters clearly inspired by The Big Lebowski (1998) (figures 8–12). Assuming the audience recognizes them, their inclusion is going to be amusing and startling, particularly considering that seeing a cartoon version of a cinematic pedophile is not something television viewers generally expect to see (figure 9). For someone who is already engaging with MLP:FIM and invested within its paratext, this will function as an Easter egg: it invokes a broader community of viewers who likewise get the gag, and by playing with the audience this way, it suggests that the creators of the show share the same sense of humor. However, for someone who isn't already engaged with MLP:FIM and its context (note 4), the same material could function as a rabbit hole, prompting viewers to reevaluate their impression of the series and investigate further. The distinction between the two exists entirely at the level of affect and mode of engagement. There is nothing in the text itself to separate whether the appearance of a pony version of The Dude or The Jesus functions as a treasure to be found or a rabbit hole to explore.

[2.6] The show specifically seeks to create a rich visual field that viewers can engage with as a treasure hunt, and it mines wider media for elements to include. To an extent, this raises what Jason Mittell calls forensic fandom, which refers to embracing "a detective mentality, seeking out clues, charting patterns, and assembling evidence into narrative hypothesis and theories" (Mittell 2009a, 128–29). It is "a mode of television engagement encouraging research, collaboration, analysis and interpretation" (Mittell 2009b, ¶2.3) that is exemplified by the statement, "We're going to need to watch that again" (Mittell 2006, 35; 2009a, 129). Mittell's conceptualization of forensic fandom was designed to account for serialized shows with complex, interrelated content such as Lost (2004–10) that go significantly further than the treasure hunts found in MLP:FIM. However, the modes of engagement and affective complexion of delight in spotting something unexpected and either wanting to know more or wanting to share that discovery with a community is something common to both Lost and MLP:FIM, even if MLP is comparatively less complex (note 5). Nevertheless, the information density can be high, despite the difference in narrative complexity; for example, 2.20 "It's About Time" has a single scene that visually references the films Escape from New York (1981) and The Terminator (1984), together with the video game Metal Gear Solid (Konami, 1998) (figure 13).

Figure 8. "Ponified" characters from The Big Lebowski in "The Cutie Pox." [View larger image.]

Figure 9. Pony version of The Jesus, complete with comparison shot of John Tuturro from The Big Lebowski. [View larger image.]

Figure 10. The Dude as a horse. [View larger image.]

Figure 11. Walter Sobchak seems calmer in Equestria. [View larger image.]

Figure 12. Donny. [View larger image.]

Figure 13. Twilight Sparkle meets her future self. [View larger image.]

[2.7] Along with the delight of sharing a discovery with a whole community of other fans is the fact these sequences highlight that the creators of the show are fans of the same media as the audience and that they have a sense of humor in how they approach their own work. Tara Strong, who provides the voice for Twilight Sparkle in the show, has a strong social media presence (@tarastrong on Twitter). She regularly discusses developments within MLP:FIM fandom, including sharing links to fan material or making teasing statements about where the story and characters might go. Lauren Faust (@Fyre_Flye on Twitter), the creator of the show, has likewise spent a great deal of time and energy communicating with the fan base, including spending time in chat channels on sites such as 4chan, which are typically risky environments for people to identify themselves, especially if they are female or have some celebrity attached to them. Both are visibly supportive of the MLP:FIM community, and this helps change the context in which people engage with the series itself; feeling that one is sharing the fun with the people who are creating it is a powerful affective distinction from feeling that one is simply consuming a product. Another side effect is to emphasize that the creators of the show are engaging with the same fan-generated content as the fans themselves, which also brings them closer together. Essentially, the creators and the fans are part of the same collective fandom, creating and consuming texts together and sharing the parts they particularly enjoy with each other. The affective register that makes the experience of engaging with MLP:FIM distinctive is sharing it with a broader community, even when they are not present, and feeling a connection to the show's creators—something that is also shared by the experience of engaging with an ARG.

[2.8] When we watch an episode of the show, along with knowing that the creators of the series are having fun with us, we are aware of how the rest of our collective fandom is likely to respond to events and points of characterization. The audience of MLP:FIM is never alone in watching the show, even when by themselves (note 6). For example, 2.07 "May the Best Pet Win!" is framed around a contest to select the appropriate pet for Rainbow Dash. This episode contains a sequence where Twilight Sparkle argues that "cool," "radical," and "awesome" all mean the same thing, to which Rainbow Dash responds, "You would think that, Twilight, and that's why you would never qualify to be my pet." Twitter conversation at the time was filled with a gleeful or tolerant awareness that elements of the community were going to be unable to leave that line alone, and that it would be the focus of a great deal of audience-generated content that used the statement as a springboard to examine the relationship between the two characters.

[2.9] The Easter eggs and rabbit holes that connect the show to a broader fandom community exist even in completely independent forms of media. Fans found encrypted references to MLP:FIM within the video game Crysis 3 (Electronic Arts, 2013) that needed to be decoded using techniques similar to those required by previous ARGs (Meer 2010a, 2010b, 2010c), with similar moments of affective discovery and achievement (Dena 2008; Veale 2012a) (note 7). On the one hand, this plays into the affective connection that the other Easter eggs promote between members of MLP fandom and a perceived community. On the other hand, it also explicitly suggests that some of the creators of Crysis 3 share the fandom. This may well be true, but it isn't a neutral claim because it also plays on the social capital that being part of the MLP:FIM community confers—in much the same way that the creators of MLP:FIM have used this connection to promote the show themselves.

3. Affect and capital in fandom

[3.1] Paul Booth (2010) uses the term digi-gratis economy to describe the dynamics within digital fandom that are a hybrid of a market economy and a gift economy. Fans spend a great deal of money on merchandise within their fandom, and this investment of market capital has a social capital within the audience, while at the same time there is sharing and reciprocity with resources. However, though it is shared freely, there is a significant underlying labor to a great deal of fan engagement, such as writing fan fiction and blogs, creating fan art, maintaining wikis, and remixing or creating music around a particular theme related to the relevant fandom. This labor wouldn't happen if the fans did not get pleasure from the effort, and part of that pleasure is grounded in the social capital it gains within the community.

[3.2] Part of what links the modes of engagement involving social capital within the communities surrounding MLP:FIM and ARGs is that both are experienced in a context of phenomenological reality. If an ARG player wants to hack into an e-mail address, he or she must possess or acquire the skills to do so; there's none of the mediation provided by a video game character, for example, who might have the ability if the players themselves do not (McGonigal 2003; Veale 2012a). Likewise, if those engaging with the MLP:FIM paratext wants to create a piece of art, remix music, or write fan fiction, then they create it themselves, using their own everyday skill sets. Both contexts of engagement are ones where people can feel legitimate pride in developing their own skills, or even in finding transferable skills that can apply to other parts of their lives (Veale 2012a).

[3.3] Christy Dena (2008) introduces the concept of tiering to understand how different forms of engagement and activity levels within communities of ARG players change individual experiences of the game. This framework is equally relevant to fandom communities. The most active tier consists of those who create their own material for the MLP:FIM community by writing fiction, creating art or music, editing video, or any of a number of such creative avenues. There is another layer of people who are deeply involved with that community content and who share what they find with the rest of the fandom community. Below them, there is a broader strata of people who engage with fan-generated material once it is located but who would not expend particular effort to find it themselves. At the base of the pyramid are people who merely watch the show. The boundaries between these levels are fluid, just as they are in ARGs, with people moving between categories, depending on their available time, energy, and motivation.

[3.4] So far, Dena's tiers are consistent with Booth's digi-gratis economy. Tiers are useful for considering the distinct affective dimensions that are involved in different forms of engaging with a fandom—a factor that Booth does not discuss. The people in the tier who actively create new material are having fun dedicating significant labor to that effort. Part of the pleasure lies in the feeling of personal pride that comes from making a name for themselves within the community as a result of the capital surrounding their contributions and as a reuslt of the fact that they are developing their own everyday skills. For example, the My Little Sweetheart book is marketed entirely on the strength of having known individuals within the MLP:FIM adult art scene as its contributors, who are only referred to by their preferred online handles. The unspoken understanding is that those who might be interested in the product will already recognize at least some of the artists and know of some or all of their work. In other cases, it is possible for creators to get some commercial recognition through sites such as Bandcamp for music, or through sales of T-shirts and other merchandise on sites like WeLoveFine.com (note 8).

[3.5] The secondary tier is focused around people who have a deep engagement with the fandom and its culture but who do not create new material themselves. Nonetheless, this tier of individuals can become known by finding new material and popularizing it within contexts such as Equestria Daily, which is one of many sites devoted to collecting, collating, and organizing contributions from the community. Simply being a member in good standing is a form of capital in allowing for the discussion and critique of other work within the community. The affects that distinguish the experience of this tier are grounded in competition in a way that is not as true for the primarily creative tier (note 9). Those creating new material might measure themselves against others, but ultimately, they are working to improve their own abilities. If someone disagrees with an interpretation of a character or wider canon, that is feedback, not something that has to be taken on board. In comparison, the secondary tier's focus on discussing the work produced by the primary tier means that disagreements and debates are inevitable, along with the kinds of energetic discussion and drama that online communities are known for. As such, the secondary tier's mode of engagement shaped by the context of phenomenological reality is also due to being able to take pride in one's work, but that work consists of communicating with other people about other artwork and news relevant to the community. People who are invested in this tier are aware that because developments in the community will keep unfolding whether they are engaged, at sleep, or at work, they could be left behind (Veale 2012a). In the same way that many people check Facebook as one of the first items in their morning routine, those invested in the secondary tier of fandom communities, such as those presented by MLP:FIM, dedicate significant energy to catching up on whatever they've missed while off-line so as to remain current and informed.

[3.6] The tertiary tier, by contrast, gets to enjoy the fruits of the more active parts of the community by engaging with the paratextual content surrounding the show. This tier has its mode of engagement shaped least by the context of phenomenological reality in both ARGs and the MLP:FIM community because its members are primarily engaging with work produced by others, rather than producing their own. They contribute contextual capital to those who are considered deserving in the form of reviews, positive feedback, and the alchemy that turns commercial engagement with fan-produced products into capital. At the same time, the tertiary tier shares the affective bonds of connection with the community even when engaging with the fandom by themselves.

4. The complex capital of endorsement and commerce

[4.1] The greatest hallmark of capital within the community is acknowledgement from the creators through the use of community-generated ideas, either within the show or in the unfolding paratext surrounding it. It is here that Booth's concepts surrounding the digi-gratis economy become particularly relevant: often official acknowledgement of community-generated material involves the creation of more merchandise for sale to that same community (note 10). This dynamic is an example of both what Suzanne Scott (2009) refers to as a regifting economy, where fan-generated content is sold back to fans in exchange for giving the fan community credibility and capital, and a process of remixing the productive output of fans, which Jeff Watson (2010) argues is a fundamental component of Web 2.0. It is also a form of capital closely associated with experiential registers found in ARGs and grounded in cocreative engagement. Essentially, the ending of an ARG is not finalized at its onset; those responsible for running the game adjust it—sometimes drastically—in response to actions taken by the player community (Kim et al. 2009; Veale 2012a). This leads to a perception among the community of people playing the ARG that they are working with the people creating it. There are many examples where players took significant steps to correct and repair problems they found with ARGs before those responsible for running them were even aware something was wrong (Veale 2012a).

[4.2] An example that tracks across several layers of official recognition and cocreative engagement is the character mainly known as either Derpy Hooves or Ditzy Doo. The character originated in an animation fault in the first episode of season 1, where she was accidentally given eyes that pointed in different directions, giving her a goofy expression (figure 14).

Figure 14. The animation fault that created a legend. [View larger image.]

[4.3] The character developed a significant fan following, with the gradual establishment of a quasi-formalized fanon character defining who Derpy is and how she fits into wider society within the show and its setting. This process tapped into both Dena's tiers and Booth's digi-gratis economy. People created a wide variety of works inspired by the character, and then other secondary works were inspired by fan-generated material, until a sufficient body of work existed that there could be said to be multiple subcanons surrounding interpretations of the character. Derpy became a site of significant affective investment: a subset of the population cared deeply about the character, whether they were primary-tier people who had created work featuring her or people in the secondary tier who had engaged with that primary work and critiqued it, or ones in the tertiary tier who simply enjoyed the fact that she belonged to the fandom in a way that was seen as special (note 11).

[4.4] The creators of the show became aware of the depth of the community's engagement with the character and began deliberately repeating her googly-eyed design in the background of scenes, explicitly folding her into the diegesis of the show. Initially, these were limited to Where's Waldo–style treasure hunts, another form of Easter egg, albeit with the distinction that the character originated within the community rather than in the broader popular culture. However, the creators of the show went further, specifically creating scenes that featured the character and eventually releasing an episode where she had a brief speaking part. Community response to this episode, 2.14 "The Last Roundup," and the cocreative engagement tied up with it was controversial; there was extensive debate about whether the creators of the show had stayed sufficiently close to fanon in portraying the character and whether the characterization was itself offensive.

[4.5] In a good example of the affective and communicative dynamics of the secondary tier of the MLP:FIM fandom community, there were several different factions that were at odds with each other, and everyone was invested enough that tempers ran high. Essentially, the different interpretations of the character within the fandom ranged from framing her as a clumsily well-meaning character with her head in the clouds all the way to her being a punch line because of being mentally handicapped. The name "Derpy" is now associated with online image memes and macros where the subject's eyes point in different directions, but in some cases, these same images have been used to make fun of the mentally disabled. Importantly, a detectable section of the fandom had no idea about the name's unfortunate connotations, or were unaware of the character's name altogether. As a result, the brief characterization during 2.14 "The Last Roundup" was seen to be invoking the more offensive interpretations by a section of the fandom. The vehemence of the anger from the fan base took the creators by surprise, and they were understandably horrified that they might be perpetuating a character who was ableist and offensive. The episode was pulled, the character was rerecorded to sound different, and mentions of the character's name were eliminated. This then caused a further backlash from fans angered that what they considered to be an accurate reflection of harmless fandom—and the capital associated with the character being recognized officially by the creators—had been needlessly ruined (note 12).

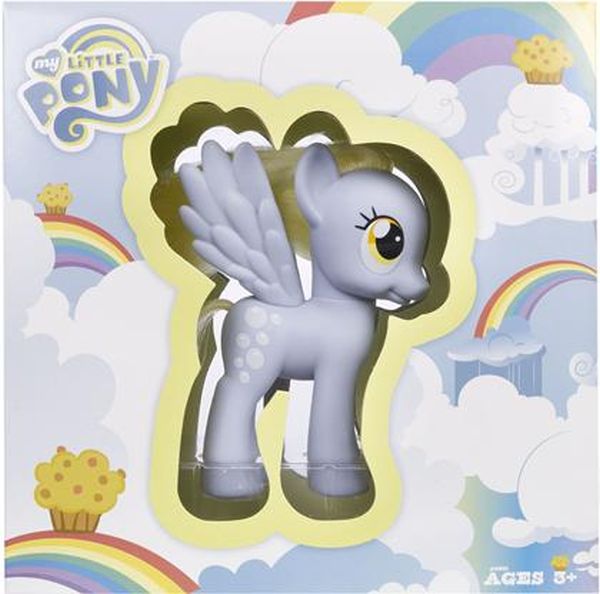

[4.6] This is an example where the complex energies invested in cocreative engagement and the digi-gratis economy turned ugly; an attempt to reinforce the felt connection between those creating the show and the fan base was instead divisive. Correcting the problem cost money for rerecording and reediting the episode, and it left no one comfortable with how their investment of capital in the character had been handled. However, the collective investment of contextual capital in the character was too great to simply abandon, and so forms of official recognition—official merchandise—that avoided the more problematic elements were created. A limited-edition toy of the character was made available at conventions such as Comic-Con 2012 and sold out rapidly. Although the toy was left unnamed to avoid a repeat of the controversy, imagery associated with the character by the community, such as muffins, were included on the box (figure 15).

Figure 15. Official recognition through commerce. [View larger image.]

[4.7] The year 2012 also saw the release of trading cards for MLP:FIM, which represented a more successful example of the digi-gratis economy: fan-generated material was used to generate commercial products that could be sold to the fan base. Several cards explicitly reference an official awareness of fanon surrounding specific characters.

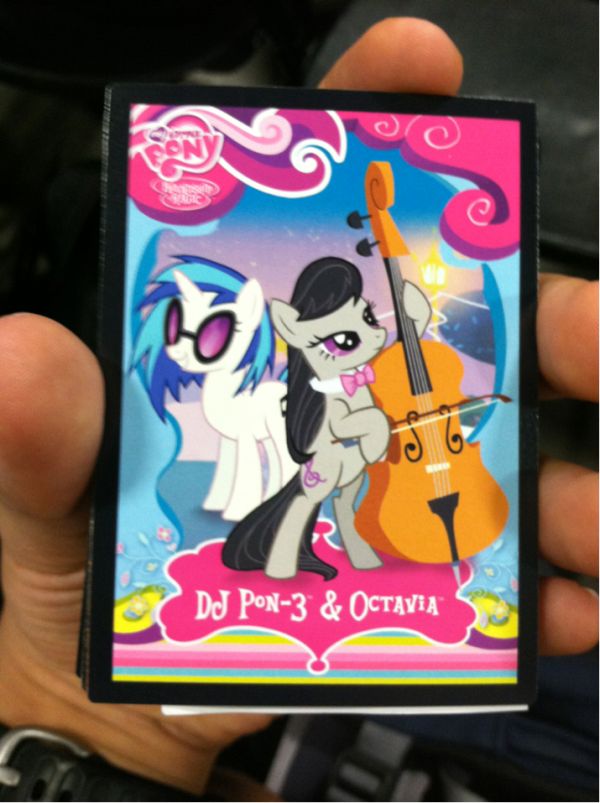

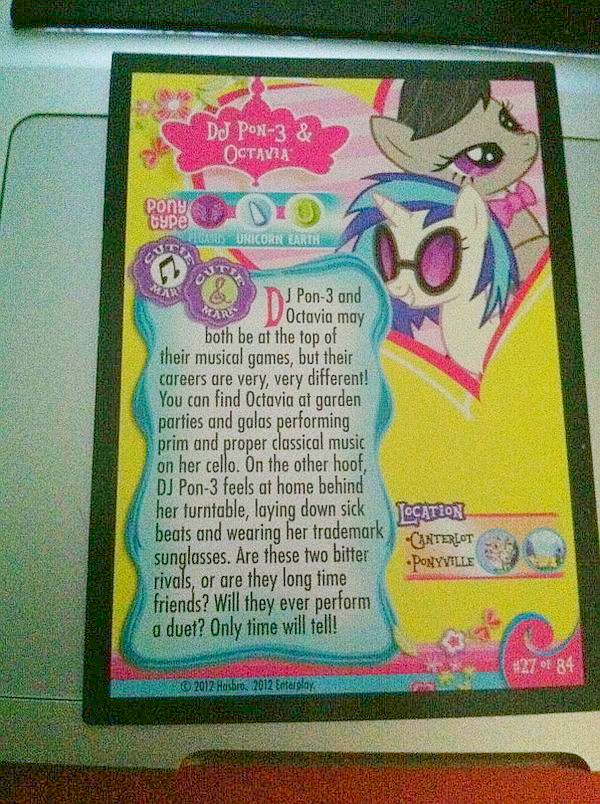

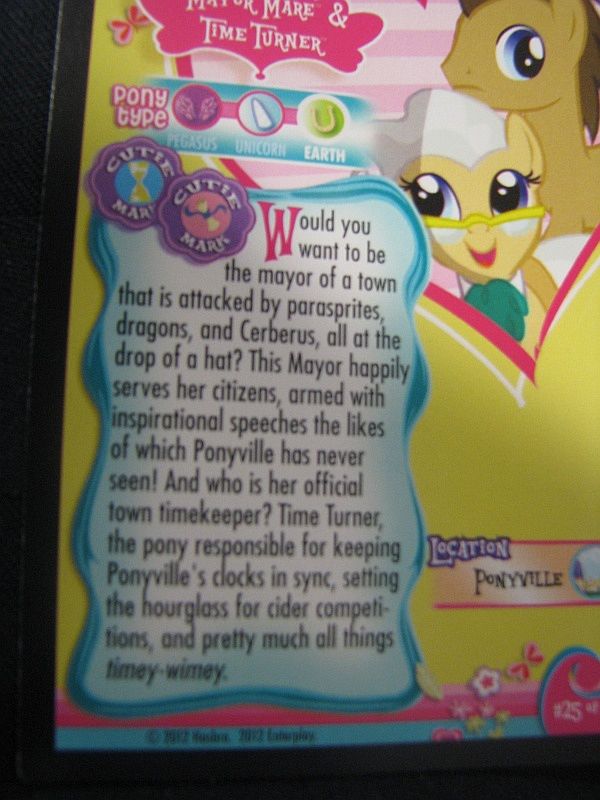

[4.8] There was considerable debate when two background characters named Lyra and Bon-Bon, whom the community understand to be in a relationship, were not sharing the same card, and delight when another card not only brought together two other background characters—Octavia and DJ-P0n3—but specifically teased viewers with possibilities about their relationship (figures 16 and 17). Another background character, who had been nicknamed Doctor Whoooves because of his visual similarity to Matt Smith's appearance in Doctor Who, appeared on a trading card with the official name of Time Turner—itself a reference from the Harry Potter series. His card specifically mentions a talent for all things "timey-wimey," referencing a quote from David Tennant's tenure as the Doctor (figure 18).

[4.9] The complex interplay within the digi-gratis economy means that there is a significant connection between finance and social capital. Fans can demonstrate their allegiance to MLP:FIM by purchasing commercial products, and in doing so, they can gain social capital within the community. It is also affective because people get pleasure and pride from investing in what they enjoy and using it to identify themselves. Interestingly, one can gain social capital from purchasing unofficial merchandise as well, which is why the decision to ground official merchandise for the digi-gratis economy in fan-generated content is an intelligent one. It means that the decision to purchase official merchandise is not just about identifying with a fan community, but also about identifying with creators who are part of that same fandom.

[4.10] Suzanne Scott (2009) has argued that commercialization of fan production by fans themselves might operate as a mode of preserving fandom's gift economy by motivating fans to compete with a co-opted framework, whereby fans are encouraged to submit work that can then be sold by the industry. However, the approach currently favored by Hasbro is not in itself neutral: the fact that fan commercialization is allowed to exist largely without interference gains capital that can be leveraged commercially. If the audience feels positively about a commercial entity, it is more likely to buy products based on that felt connection. There have also been specific occasions that triggered a backlash against what is taken to be gratuitous commercialization, where the community response is far less positive. Examples include Twilight Sparkle's transformation into a princess at the end of the third season, and the development of the Equestria Girls spin-off movie that frames the six main characters as human teenagers at high school (note 13).

[4.11] The general understanding is that there has been sufficient connection and support of the fan base by the creators that they are not simply being manipulative, and that they have earned some trust. The audience members are aware that they are engaging with a commercial product. They understand the business model and are mostly accepting of it—particularly because of the capital the creators have gained in their dealings with the fan community:

[4.12] Every season Hasbro makes demands. They need a new pink princess pony and for Twilight Sparkle to have a brother. The board wants to see crystal ponies because the buzzword "crystal" anything is popular with girls 4–8 years of age. And now, they want Twilight Sparkle to be a princess, because Hasbro is not like us…Unlike all of us, Hasbro is convinced that being smart and capable and open to learning and new experiences—the myriad of character traits for which we love a certain purple unicorn, are unimportant. Their priority is rushing the character into being a princess because retailers don't want books as accessories with girls toys, they want dresses and flowing hair and weddings and yards of pink material. BUT, and this is the important bit, these demands are being filtered through artists and writers and directors who do understand, who ARE like us…This is the same team that took an out-of-nowhere pink princess and made her into both a creepy insectoid monster queen AND a highly capable and good-hearted heroine who returns from exile to buck tradition and save her prince. These are the crafters of a show we love and appreciate—they know what we want to see, they believe in the work they produce and the world they have been building for three seasons. (Pixelkitties 2013a)

[4.13] Part of what has convinced MLP:FIM fandom that the creators actually want to be part of the community, rather than to simply leveraging it for commercial gain, is the noncommercial interactions that also unfold in the digi-gratis economy.

Figure 16. Front of card. [View larger image.]

Figure 17. Back of card. [View larger image.]

Figure 18. "Timey-wimey." [View larger image.]

5. Affective capital for its own sake

[5.1] Many people who identified with being an official part of producing MLP:FIM have spent time engaging with the fan community on their own time, without direct financial motive, in many cases because they find it fun. As mentioned earlier, Lauren Faust braved the depths of 4chan to discuss the show with fans; she has also become involved in sponsoring a fan-generated fighting game based on the MLP characters, despite a cease-and-desist order from Hasbro (note 14). Tara Strong directly references artwork and creative engagement from the community via social networking, including demonstrating a playful acceptance of sexualized content within the show's paratext. The sheer glee that members of the MLP:FIM community display when she or one of the other creators references some of their work or even requests a piece of art is wonderful to behold, and this is a significant part of what underlies the perception of cocreative engagement within the paratext of the show. Strong also creates material for the fandom herself, outside of her involvement with recording voices for the series: on March 7, 2012, she tweeted a section of a hip-hop song written in character as Twilight Sparkle in her stage persona (note 15). The community quickly seethed with excited responsesincluding the "Twililicious" image by John Joseco released on March 19 (figure 19). There was some confusion and debate within the community about which element had come first—the artwork from Joseco, or Strong's tweet—and there was great excitement at early speculation that she had made the post in direct response to the artwork in an example of true cocreation. However, although the relationship actually moved the other way, Strong has since adopted Joseco's "Twililicious" as the background image to her Twitter account—a serious coup for both social capital in the digi-gratis economy and the idea that the MLP:FIM paratext is a collaborative effort.

Figure 19. "Twililicious" by John Joseco (2012). [View larger image.]

[5.2] Perhaps one of the more dramatic embraces of noncommercial benefits of the MLP:FIM digi-gratis economy is the #LasPegAssist fund-raising effort in the wake of the MLP:FIM Unicon convention in 2013. The convention focused on MLP:FIM fandom and invited voice artists and other members of the creative team as paid guests, along with raising money for various charities. Whether as a deliberate scam or simple incompetence, the convention collapsed financially. No money was paid to any of the guests for their attendance, none of the money raised and earmarked for charities was passed on, and many fans were financially stung as the hotel recouped funds by charging for what would otherwise have been compensated rooms. The #LasPegAssist hashtag was created on Twitter when members of the MLP:FIM community began raising money to pay for the guests left unpaid and out of pocket for travel, food, and hotel costs, and it snowballed as more members of the community became involved. What had begun as emergency efforts focused on gathering funds for the convention's headlining guests expanded in scope, and the guests from the creative team themselves began to participate. They suggested that because their emergency had been solved as a priority by the community's response, the effort could now refocus around the charities, vendors, and fans likewise left out of pocket. Tara Strong and John de Lancie waived the appearance fee they were each due, writers Meghan McCarthy and Amy Keating Rogers offered up the shirts off their own backs for auction to contribute to the effort, and other members of the creative team began raising awareness about the fund-raising and donating behind-the-scenes merchandise and production notes. By the time #LasPegAssist closed, the collective MLP:FIM community had raised nearly $20,000, and everyone disadvantaged by the collapse of the convention—including charities—had received money equivalent to what they were owed (note 16). It is telling that the thank-you notes on the #LasPegAssist Web page use people's online handles: the appreciation that matters comes from within the community.

[5.3] The #LasPegAssist effort showcases the kind of fund-raising normally seen in a campaign to save a television show from cancellation or to otherwise harness the spending power of a fan base for a particular commercial purpose. In this case, the motivation many people mentioned was a refusal to see MLP:FIM conventions and fandom at large tainted by financially harming those who had given their time and personal capital as creators to the cause. The fans banded together to raise emergency funds for the creators, after which the creators began helping the fund-raising effort to assist disadvantaged fans. In the process, they collectively auctioned items worth a great deal of capital within the digi-gratis economy. Ultimately, fans could help fans and at the same time collect some of that capital for themselves.

[5.4] In stark comparison to the controversy surrounding Derpy Hooves, this event served to profoundly reinforce the perception of a cocreative community encompassing both the creators and fans of MLP:FIM (Pixelkitties 2013b). The pride and investment in community spirit surrounding it has been significant, even as the effort itself displayed the same tiering and affective distinctions as the wider fandom itself.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] The modes of engagement that shape the community experience of MLP:FIM have a great deal of experiential overlap with those found in ARG communities.

[6.2] The affective register that makes the experience of engaging with MLP:FIM distinctive is sharing it with a broader community, even when members are not present; and feeling a connection to the show's creators in collaborating on a project still under development that everyone is invested in. The text and paratext combine to provide a large number of distinct and independent points of entry into engaging with the series that are analogous to the rabbit holes found in ARGs, each of which will shape the impression and mode of engagement that a viewer will carry into the show. Just as with ARGs, the community is made up of multiple modes of distinctive experiential engagement that individuals move between over time.

[6.3] When I say that considering MLP:FIM and the community surrounding it through the lens of an ARG produces useful analytical insights, I do not mean that it is unique in this regard; considering media forms and franchises in terms of how their modes of engagement shape experience will open many productive doors in comparing texts that would not outwardly seem to be similar. This is an approach I intend to explore further in future work.

7. Acknowledgments

[7.1] Many thanks to Jason Gill for tireless efforts in locating relevant developments within MLP:FIM fan culture. Thanks also to Robert Harris of DustyOldBooks.net for help sourcing academic sources on brony culture, and to the denizens of RPG.net's "Other Media" forum for supplying an endless stream of examples and useful material.

[7.2] Additionally, Mark Stewart, Dr. Suzanne Woodward, and Dr. Laurence Simmons of the film, television and media studies department of the University of Auckland kindly offered assistance in providing access to university resources during the review phase, which is greatly appreciated.