1. Gotham City 14 miles: The superhero in the garage

[1.1] In the United States, 1966 was the year of the bat. On January 12, Batman (ABC, 1966–1968) burst onto American television sets, launching an unprecedented wave of Batmania. This craze for the show was primarily distinguished by a glut of merchandise aimed at children, and like Bruce Wayne, fans could exercise economic power in order to (at least symbolically) transform themselves into the Caped Crusader. However, the series also inspired nonauthorized and amateur productions. These ranged from fan films to garage band novelty songs like "Who Stole the Batmobile" by the Gotham City Crime Fighters (who dressed as Batman and Robin). The production, rather than simply consumption, of texts and objects more intimately linked the fan to the bifurcated figure of Bruce Wayne/Batman because the Batman persona and all of his attendant bat-branded objects were made by Bruce Wayne in the comfort of his home. And no object was more popular, or more immediately identified with Batman's crime-fighting or a more potent symbol of Bruce Wayne's wealth, than the Batmobile. As Lorenzo Semple Jr., the show's principal screenwriter, told producer and creator William Dozier during the development of the series, "I can tell you that we've created one absolutely guaranteed new TV star: the Batmobile" (Garcia 1994, 28). The vehicle was created by custom car designer George Barris (following the design sketches of 20th Century Fox production artist Eddie Graves), who based his design on the Lincoln Futura, a concept car made by Ford in 1955 (figure 1). The Batmobile was the ultimate car as extension of owner; it literally and figuratively embodied Batman. As Barris recalled, "I incorporated the bat-face into the design sculpturing of the car. That's why you see the ears go up where the headlights are. The nose comes down for the chain slicer. The mouth is the grill. Right on back to the huge long fins which are the Bat-fins" (Garcia 1994, 29). Like that other iconic car of the 1960s, James Bond's Aston Martin, the Batmobile was not simply a mode of transportation but a mobile laboratory of crime-fighting gadgets and state-of-the-art refinements. These included an atomic-powered engine, an antitheft device, bat armor, a mobile crime computer, an emergency bat-turn lever, seat ejectors, and a parachute for emergency stops.

Figure 1. The 1955 Lincoln Futura. [View larger image.]

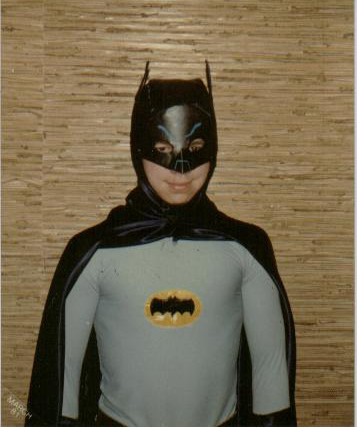

[1.2] The Batmobile was, in other words, the fantastic reimagining of that singular postwar symbol of success and freedom in America, the automobile. It is not surprising then that it became one of the most popular elements of the series. A fan such as Mark Racop was hardly alone in his adoration of the Batmobile. Born in 1965, Racop cannot remember a time when he was not a fan of the series. Growing up in the small city of Logansport, Indiana, he had two ambitions: to become a filmmaker and to have his own Batmobile like the one on the show. In the 1980s he fulfilled both ambitions, making and starring in three amateur Batman films (figure 2) and building his own Batmobile for the last one, Eyes of the Cat (1983). Driven by the desire to build a better replica of Barris's iconic car, Racop created version after version, until finally in 2004 he built a model of the car that sold at auction for over $85,000. His pursuit of the perfect custom Batmobile continues, and today he is the owner of Fiberglass Freaks, an auto body shop dedicated to making replica Batmobiles. Racop's cars sell for $150,000, and his shop is the only one in the world officially licensed by DC Comics to make replica Batmobiles. Meanwhile, he also owns and operates MagicHouse Productions, his own film and television studio in Logansport, realizing his other childhood dream.

Figure 2. Racop as Batman for one of his amateur films (1981). [View larger image.]

[1.3] In a 2-week span in January 2013, two events occurred that, in very different ways, reaffirmed the ongoing appeal of the car from the series. Barris's original Batmobile sold at auction for a staggering $4.62 million, and Allyson Martin, an 18-year-old woman with terminal cancer, went for a ride in one of Racop's custom Batmobiles. Martin was a tremendous fan of the car, and her friends arranged for her to visit Racop's shop in order to fulfill her dream of riding in the Batmobile. If the auction confirmed the commodity value of the car (and probably made its new owner feel as much like Bruce Wayne as Batman), Martin's ride confirmed its social value as a personal expression of individuality and escape. Racop's encounter with Martin also allowed him to actualize a very Batman-esque ethos of good citizenship.

[1.4] In their rhetorical intersection, each event speaks to the utopian value of the superhero object as a commodity and as a symbol of transcendence. This is the primary significance of the superhero: he or she is intimately linked to society but also always transcends its limits. If a superhero such as Batman is always ritualistically performing that transcendence in the shift from secret identity to superhero identity, his objects come to stand as fixed representations of his ideals and the link between identities. It is through objects that the superhero and the superhero fan negotiate the perpetual slippage between the quotidian and the fantastic. Both are always in a locked groove movement between terminal points in the perpetual motion of becoming.

[1.5] The sign that Batman races past when leaving the Batcave on the 1960s television show reads: "Gotham City 14 Miles." Batman is always speeding to the center of Gotham to save it and to reassert his own meaning in the process, only to retreat to the Batcave, consummation of final meaning avoided. For fans, Batman can never reside in the past, only in a perpetual present moment that is blurred into the past by the impulse toward the future. Subjectivity must be felt, in other words, in order to have meaning. For the Bat fan, the Batmobile is a common means by which that meaning can most directly be arrived at. With a Batmobile, that idealized self is always just on the horizon; Gotham City is always just 14 miles away. As Racop says of his Batmobiles, he is constantly striving to make the perfect replica of the original vehicle. If a concept car is a utopian design for the masses, then the Batmobile demonstrates how a custom car is a utopian design for the individual. A custom Batmobile is the ideal object by which the inherent contradiction between the mass and the individual can be navigated. Behind its wheel, the driver is intimately a part of a collective memory of a childhood wish to always be somewhere and someone better.

2. Out of the Batcave: An interview with Mark Racop

[2.1] Q: Do you have any primal memories of the TV show from your childhood?

[2.2] A: My mother says I was a fan of the 1966 Batman TV show since I was 2 years old. I can distinctly remember my very first episode of Batman, where Robin was tied to a printing press, about to be stamped into a comic book. I also remember Robin on the buzz saw with the Riddler. I was at a babysitter's house while my mom was pregnant with my brother. I fell in love with the TV show, the music, the action, the color—everything about it was fantastic, but I especially liked the car. The flamethrower, peeling out of the Batcave, driving over the folding danger sign—that car left an indelible impression on me. That was the most beautiful car in the world. It was so much better than my parents' Volkswagen bug! I promised myself that someday I would own that car. Fifteen years later, this crazy kid talked four other crazy 17-year-olds into tearing apart a 1974 Monte Carlo and turning it into the Batmobile (figure 3).

Figure 3. Racop (left) has an early encounter with the fetish object (1975). [View larger image.]

[2.3] Q: Not exactly a Lincoln Futura.

[2.4] A: No! The Monte had the wrong wheelbase, the firewall was too tall, and it had other issues. But we finished the car. It was not a prototype but more proof of concept.

[2.5] Q: So what led you to building 1966 Batmobiles?

[2.6] A: I made a Batman fan film in 1980, shot on Super 8 movie film. It was pretty ambitious for my first foray into filmmaking. Most people start with a short film; I started with a feature. We had lots of people in the movie, including the current mayor of Logansport. Our second film was even more ambitious. For the first two fan films, I cut footage in from the TV series, but by the time I was in college, making our third Batman fan film, I wanted to have the ultimate prop. Necessity was the mother of invention. It took three summers to build Bat 1, version 1. We had no tools and no auto body experience, and only four photos and a Corgi toy Batmobile from which to build the car.

[2.7] Q: How did you learn to do this?

[2.8] A: We were completely self-taught. I had some advice and help, but I basically taught myself fiberglassing, body filling, and mold making. There was no Internet back in those days. We used every material that we shouldn't have: plywood, paneling, even duct tape! Hindsight being 20-20, we should have pulled a mold from the car, cast a new body, tore off the buck (the sculpture from which you pull a mold), and replaced it with a nice, perfectly even fiberglass body like we do today.

[2.9] Q: What was the process to get you to where you are today?

[2.10] A: Fourteen years ago, I brought in some professionals to help me redo Bat 1. Between version 1 and version 2 of the car, my dad recorded all 120 episodes of the TV show for me, and I went through every Batmobile scene, frame by frame, taking lots of notes and making lots of drawings. We tore off the back half of the car and redid it. One of my friends brought in all kinds of experience, tools, and other professionals. I told him someday this could turn into a business. He thought I was crazy; he didn't believe anyone else would ever want a Batmobile. We went to an auction in Auburn, Indiana, and saw a 1966 Batmobile replica not sell for $140,000 (because it didn't meet the reserve). We looked at each other and said, "Oh yeah, we can do that, and we can do it better." We bought a Lincoln Town Car and started sculpting our own Batmobile buck from yellow urethane foam with the intent of popping a mold.

[2.11] But things changed when we found the "Futura in the Woods," the nickname given to a replica sculpture of the 1955 Lincoln Futura. The original Lincoln Futura was a metal concept car, and there was only one ever built. Famed sculptor Marty Martino loved the Futura. He was such a fan of the Lincoln Futura that on January 12, 1966, while everyone else fell in love with the Batmobile, he was screaming. He was mortified to see what Barris had done to this beautiful one-of-a-kind concept car. He made it his life's ambition to build a 1955 Futura tribute car. He built a buck from wood, chicken wire, cardboard, and body filler. Unfortunately, though, it sat out in the woods for 12 years or so and was starting to fall apart (figure 4). Marty needed to sell it, or he was going to have to trash it. He put it on eBay. I bought it for $2,125. We got there and saw the Futura in the Woods in person for the first time. We quickly realized that every square inch of the car was going to need major body work. It required 3 months of work before we could pop the mold. Strangely, the major damage only took a few days to fix, but the body work required a tremendous amount of effort to get the buck to a point that was satisfactory. But that was the turning point for us.

Figure 4. Utopia deferred: the "Futura in the Woods." [View larger image.]

[2.12] My business partner at the time wanted to convert the Futura into the Batmobile and then pop a mold. I said no, this is a rare car. There's the Futura replica that the late Bob Butts made, and this buck. That's it. We need to maintain this as it is. Besides, somebody might want a Futura someday. So we made a Futura mold, cast a Futura body, then started converting it into the Batmobile just like Barris did to the original metal Futura in 1965. Using high-res photos I took of the #1 while it was in Indianapolis—this was really high-tech—I used an opaque projector to get the scale right, and then I traced the wheel wells, projecting onto the nose of the car to get the beak right, the scallops on the ends of the wings. We used this method to make sure that we got the dimensions right. Then we made a Batmobile mold.

[2.13] Our first Batmobile, we took to the same auction in Auburn, Indiana. The year before, the car got up to $140,000, so we're thinking—Oh, this will be great, we'll get $100,000, maybe $125,000. It stopped at $85,300. We were disappointed. I mean, really? Did we miss something? Other Batmobiles had sold for far more than that, and they weren't nearly as nice. So we thought, let's build another one and see what we can do. Five months later, we sold our second car at an auction for a very, very paltry $70,100. We thought, wow—we've really, really missed. Something is really, really wrong. We almost closed the business over it.

[2.14] Q: What year was this?

[2.15] A: Let's see—2003 is when we started the business. Our first car was auctioned in September—Labor Day weekend—of probably 2004, and the second one was May 19, 2005. But then things changed. Shortly after we auctioned Bat 3, we got our first nonauction order, a customer-ordered car. The runner-up bidder from the auction called us 2 weeks later. He said he wanted to order a car. We finished his car and put a video on YouTube called "Batmobile Delivery Day." We had 50,000 hits in less than a month. We sold four cars in 2 weeks. That is when everything changed.

[2.16] Q: So, since that point in time, how many Batmobile replicas have you sold?

[2.17] A: Twenty.

[2.18] Q: Who buys these? Is there a profile of a typical buyer?

[2.19] A: Yes, there is a profile of these very unique, zany individuals. They are 40 to 65 years old. They typically own their own business or are high up in their business. They are decently well-off. They have to be because it is an expensive toy—not something that everyone needs. While everyone wants one, not everyone needs one. They cross-geek into James Bond, Star Trek, Star Wars, Mission Impossible, the Monkees, Get Smart, and all of that. There is an incredible amount of camaraderie that we develop between ourselves almost immediately, and between themselves, too. We have had a couple of Batmobile gatherings were about 40 people came together. We had one at Barris's shop in North Hollywood.

[2.20] Q: What do you do when you get together?

[2.21] A: We just geek about the car. We talk about the details, the misrepresentations over the years, the things that have been changed from 1968 until today, and things like that. Accuracy, for me, is king. I want the car to look like it did in episode 1, season 1 of the TV show. It's quite a contrast to what it looks like today, which is horrendous. I interviewed George Barris for a DVD that we put out. That is why I was able to take a lot of high-res pictures of the interior of the #1—parts of the car that no one had ever photographed before. All of my customers enjoy the car, but not necessarily all of them enjoy the show. That was very interesting to me. Some absolutely love the car but don't like the show—it's too corny, too weird, etc.—so there is a lot of that.

[2.22] Q: Do you have clients then that are more car aficionados while others are more Batman or pop culture aficionados?

[2.23] A: Yes. You do get a very interesting cross section of those growing up in the 1960s. If they were 6 to 12, that's the age that loved both the show and the car. If they were a little older than that, if they were 12 to 16, they loved the car but not the show. From a pop culture standpoint, it was very interesting. Batman worked on two levels. If you remember watching the show, it was great action adventure for the kids. As a kid, I don't remember the "bams," "biffs," and "pows." I was so into it that it didn't even register. Then I saw the show again as a 12-year-old and I thought, "Are you serious? Really?" At 12 to 16, the show doesn't really work. But then as you get older, you start to get the well-oiled clichés and jokes. Batman producer Bill Dozier knew he had the right formula when he received a letter from a father that said his 8-year-old son kept saying, "Daddy, stop laughing—this is serious!" It hit perfectly. That preteenage age, that's where it didn't work, and those are the ones that don't like the show. And those are the ones that probably have never given it a second chance (figure 5).

Figure 5. Racop behind the wheel of one of his replicas (2008). [View larger image.]

[2.24] Q: If I wanted to leave here with a brand-new Batmobile, what do I have to shell out?

[2.25] A: Up until this point, the price tag had been set at $150,000, but starting March 1, we've started offering both a lower-priced car and a higher-priced car. I've done some marketing research—and my surveys have shown that's the case. $150,000 is a weird price point that doesn't work for people. They either need a lower price tag because that's what their budget allows, or price isn't a concern and they want more features. So that's why we're going to offer a $100,000 car and also a $270,000 car. The $270,000 car will have a 625 horsepower engine, a performance monster transmission, a Currie rear end to get that power to the ground, and a custom-built chassis with air ride suspension, to raise the car for driving and loading in vehicles, but be able to drop it down to the ground to make it look just like the original car. GPS, satellite radio, and all kinds of modern gadgets to spice it up, and a real chrome interior to match the #1 perfectly. And then we'll offer the current car as a midrange car for those that still want something like that. The $100,000 car will pretty much be a stripped-down model as far as features go. It won't have the flamethrower, the working Batbeam, working dashboard, detect-a-scope. It will have Mustang seats instead of Futura seats, but it gives people a chance to get their foot in the door, and if they want those features later, they can add them.

[2.26] The Batbeam is just a radio antenna—an automatic antenna that raises and lowers. But apparently—and I'm shocked by this—for whatever reason, that's the firework of the car. I mean, you've got the flamethrower, but everyone expects it, and that's the biggest feature of the car, and everyone goes bananas for that, but the next one is the Batbeam. The antenna grid, the gold antenna grid sitting in between the front windshields, when it raises and lowers—Ooooo. Ahhhh. Ooooo. What? You've never seen a power antenna before? But everyone seems to go bananas for it just because it's another feature that they're not expecting. And then electric actuators open the hood and the trunk of our cars. That's unexpected as well. They're not looking for something like that. Then we say, oh by the way—we have a rearview camera that plays on the LCD screen on the dashboard. The detect-a-scope has a green flashing light and other lights, and now even sound effects in our current cars. You put all these things together, and it really starts to add up fast as being exciting.

[2.27] Q: No ejector seats?

[2.28] A: No ejector seats. No, and no working parachutes, either. A friend of mine in LA built a Batmobile replica, and he put working parachutes on his car, and he used them once. Once. He was going 40 to 50 miles per hour, and he popped the chutes. Not expecting, I guess, that they actually do something—like on the drag strip; they stop the car! Well, on the road, they stop the car too. He hit his head on the steering wheel and just about knocked himself out. So I said, you know what, I've got enough to worry about. So we use real parachute packs, but the contents are fake. He also, apparently at one time, had some kind of a seat ejector, an actuator to raise the seat, but he said after having to clean up a mess or two, he deactivated that.

[2.29] Q: Can you explain how this all evolved and you became an authorized Batman Batmobile maker?

[2.30] A: From 2003 to 2007, it was a gray market. Pretty much people could do that kind of thing and not expect trouble from DC or Warner Bros., unless they were using their cars to make a ton of money, or to advertise a product or advertise a business—then they would stop that. In 2007, the world changed. They started using the trademark. They gave Mattel—Hot Wheels—the license rights to start producing 1966 Batmobiles. For the first time in 40 years, they remembered, "Oh yeah, huh. We've got this 1966 Batmobile thing, and this whole 1966 TV series thing that we might want to look at." I received a cease and desist from DC Comics. I called them immediately and said, we're not licensed, so … what does it take to become licensed? Oh, no, no, no, they answered. We're not going to license you or anyone else. That's never going to happen. We've discussed it internally, and it's not going to happen. I replied, no, seriously; you're in business, I'm in business—let's make this a win-win. No, no—it's never going to happen, he said. So, okay. I hired the best trademark attorneys in the Midwest, Barnes and Thornburg, and went toe to toe with DC Comics. We said, look, you don't have anyone else licensed, you are not losing any money out of it, and a licensee is not losing any money, either, so really, we don't see what the problem is. Again, if you would like to license us, we're good to go. After a year of back-and-forth discussions between the attorneys, they said, we're not going to pursue this any further. I thought, that's odd, but hooray. Then I'm over in England, helping a guy mount his Batmobile body to the chassis of the car, and I get this e-mail from my attorney from Barnes and Thornburg, and he said, you'll never believe this, DC just called and said, do you think Mark would consider licensing? Then the ball started rolling! In October of 2010, we had a contract in our hands for licensing, to be able to build these cars as officially licensed vehicles. So everything changed—anybody else trying to build Batmobiles is no longer in a gray market; they are in a black market situation.

[2.31] Q: That's impressive. They wouldn't just rubber stamp anybody to do this.

[2.32] A: They sent a spy to the shop, pretending to be a customer. He liked what he saw and reported back. And DC admitted that they sent a spy to the shop! I didn't know at the time, but they said that everything was good, and the quality level was at a point where they felt compelled to license somebody finally. They had seen many other replicas and they were all awful. And they are—most of them, anyway. It's sad to see most other replicas, but now the ball game is so different. Because we are licensed, and because DC is heavily marketing the Batmobile, nobody else can use the same defense that we did back in 2007 (figure 6).

Figure 6. Barris poses with his most famous creation. [View larger image.]

[2.33] Q: What are your thoughts on the auctioning of Barris's original Batmobile?

[2.34] A: I was there. I was about six people deep from the rear of the car on the auction block. To describe the crowd in any other way than electric would be an understatement. When that car rolled in and was up on the auction block, everyone stood up. People that have been going to that auction for 25 years said they had never seen anything, anything, like that before. One of the auctioneers said, "You know, I've been telling people all week that we had been hyping up the Batmobile a little too much. I guess I was wrong." It is a piece of television history. It is an icon. It is more than just a vehicle. The car is a character. It is not a useful item. There's a useful item under it, but the car itself, the design of that car, is an icon, and it is a character, and that is why it struck such a chord. The car itself, if you would think of it from only an automotive perspective, is probably only worth only $50,000 to $100,000 in its current shape because it's in really bad shape. They cut away part of the frame when they changed out the transmission, and they never replaced it. That's why the car was so springy when they stopped it—it would bounce so badly because the car is cut in half in the middle. Because of it being a piece of television Americana, that is what makes it worth the other $4.1 million.

[2.35] Q: Does it feel nostalgic, this relationship you have with the Batmobile?

[2.36] A: That happens. I do feel younger when I drive one around town, to be sure. But—I don't know—it's so multifaceted for me, anyway. I don't drive around town to feel young, to remind me of my youth. I drive it around because I enjoy it. It's neat to be able to go out to the shop and just sit in one and go, I'm sitting in a Batmobile! How cool is this? It doesn't get any better than that!

[2.37] After I built Bat 1, at three in the morning I would just go out and just sit in the car because I can't believe this—it's right here. So enjoyment is big part of it, but it's grown to be more than that as you start to see the reactions of people and you realize that you are able—with just a car—to spread some joy out there. And you really get to the hearts and minds of people. Whether they've seen the TV show or not—it doesn't seem to matter. It doesn't matter their age; it doesn't matter their gender; it doesn't matter their nationality—everyone honks, smiles, and laughs and has a great time when they see the Batmobile. It's really been an honor to carry out that tradition that George Barris started back in the 1960s, and carry that on today, especially when we've got somebody like Ally Martin, who's dying of cancer, and one of her last wishes was to ride in the 1966 Batmobile.

[2.38] Q: What was her attraction to the Batmobile, and how did you two meet up?

[2.39] A: She's not a fan of the show at all, but she loved the car, absolutely loved the car. A friend of the family found out she is a huge fan of Batman—from the movies, somewhat from the comics, but mainly from the movies—but she fell in love with the 1966 Batmobile from the TV show. That mutual friend called me about 4 months before to set up a ride for her. I said, yes, absolutely. But every time we set up do it, Ally's health took a turn for the worse. It just about didn't happen. Even a week before, she was in really bad shape—she couldn't keep any food down. But they got that worked out, and they came in from eastern Ohio. I took her for a ride, and took her friends for a ride, and we just had a ball.

[2.40] Q: When you drive the Batmobile, do you ever dress up as Batman?

[2.41] A: I did for some birthday parties back in the 1980s and 1990s. It's not the safest thing to do. That cowl cuts off the peripheral vision.

[2.41] Q: Let's go look at some cars.

[2.42] A: Sounds great! To the Batmobile! (figure 7).

Figure 7. Individualism, assembly-line style. A collection of Racop-made Batmobiles. (Photo by Rich Vorhees.) [View larger image.]