1. Introduction

[1.1] In April 2012, UK media was overrun with reports about a book series that had recently hit the shelves. Fifty Shades of Grey and its two sequels, Fifty Shades Darker and Fifty Shades Freed, authored by British writer E. L. James, proved wildly successful; much of the media attention devoted to the series focused on its erotic content. The books center on virginal college student Anastasia (Ana) Steele and her BDSM relationship with billionaire CEO Christian Grey. A second area of media interest, however, lay in the series' genesis as Twilight fan fiction. Debates took place in fandom on the ethics of pulling fan fic and publishing it as original work. Implicit in this conversation were the notions of a gift economy versus Web 2.0 notions of fans as prosumers, this making evident the tensions between these concepts of fan production.

[1.2] James originally wrote and published Fifty Shades of Grey and its sequels as a multichapter fan fic under a pen name. The fic was well known in the Twilight fandom; it had been published on FanFiction.net before moving to James's personal Web site after FanFiction.net removed the work for violating its terms of service on mature content. After this move, the series was picked up by The Writer's Coffee Shop (http://www.thewriterscoffeeshop.com/), an online publishing house formed by Twilight fans that specialized in publishing pulled-to-publish fan fiction—that is, fan fiction that has been removed from the Web, has character names and descriptions changed, and is published commercially as original fiction (Tan 2012) (note 1). The Writer's Coffee Shop published the Fifty Shades novels in e-book and print-on-demand format until they were picked up by Vintage, a Random House imprint, in 2012.

[1.3] Fifty Shades became the best-selling book of all time in Britain, with e-book and print sales topping 5 million copies by the end of summer 2012, not to mention the more than 65 million copies it has sold worldwide to date (note 2). Despite this, however, the book has been derided by critics, readers, and Twilight fans alike, although not always for the same reasons. The Fifty Shades trilogy brought BDSM to a wider mainstream audience, and with that came both feminist and BDSM critiques of the series. The blogger Smash (2012) argues that Fifty Shades' promotion of BDSM reveals the way in which BDSM is culturally identical with domestic violence. Similarly, an English domestic violence charity called for copies of the book to be burned in protest against its normalizing of violence against women (Flood 2012a). BDSM activists have countered these arguments, however, arguing that the series demonizes, rather than depicts, BDSM. Pamela Stephenson Connolly (2012) suggests that the character of Grey is "portrayed as a cold-hearted sexual predator with a dungeon (that word has been wisely swapped for 'playroom'), full of scary sex toys. Worst of all is the implication that his particular erotic style has developed because he is psychologically 'sick.'" The quality of the writing was also criticized in the mainstream press. The Guardian announcement that the trilogy had been nominated for the National Book Award in the category of popular fiction book of the year (Flood 2012b) garnered comments such as, "With the greatest of respect, why don't they just call it the Shit Books Award?"; "Fifty Shades of Grey is hilarious…full of clichés and so contrived," and "Can I submit a copy of Razzle or Penthouse for the NBA, if it's open to pornography?" Both popular and critical discourses thus denigrate the novels as lacking in literary merit while positioning the commenters as in possession of more cultural capital than Fifty Shades' fans (Harman and Jones 2013).

[1.4] Fannish commentary also shares these critiques, criticizing the books for their bad prose, but fandom also has its own set of concerns, which draw on different discourses than those of the mainstream press. A search for Fifty Shades of Grey on the blogging platform LiveJournal reveals a number of communities dedicated to criticizing the series. Positioned as sites of antifandom (Gray 2003, 2005, 2006), these communities contain links to parodic videos such as those in the "X reads" series as well as dedicated entries sporking the trilogy (note 3). Among the critiques raised against the series in these entries are Grey's predatory and abusive actions; the presentation of stalking and controlling another person as romantic; the misrepresentation of BDSM; and the poor quality of the prose. With the publication of Fifty Shades of Grey, fans expressed concerns about its impact on fandom. As blogger audreyii_fic (2012) writes, James is "embodying the worst stereotypes about fan fic writers. That we're lazy, that we lack talent, that we're leeching off the 'real' creativity of others. It makes every last one of us look bad." Beyond fandom at large, however, Twilight fans are critical of James and Fifty Shades. Bonnie, commenting on Aja Romano's article "50 Shades of Grey and the Twilight Pro-fic Phenomenon," writes,

[1.5] Terrible plot, terrible character development, and terrible writing are what "Fifty Shades" is, and many of us in the Twi fandom are truly embarrassed that this is the fic that puts us on the map. There are far better writers in the Twi fandom who deserve this success—Debra Anastasia and Jennifer DeLucy are a few. Unfortunately this poorly written and poorly edited soap opera that was "published" to line James's and TWCS's [The Writer's Coffee Shop] pockets gains fame. It's a truly sad day for our fandom…On the other end of this is the growing number of our writers leaving our community, either pulling published and WIP fics in the hopes of becoming the next E. L. James, or out of disgust for the now mercenary attitude of some writers. Some have, in fact, posted that if you want to know the end to their story you have to "buy the book." What makes a fandom work is the respect and trust that the writers and readers have for one another. James and TWCS have betrayed this, and many of us fear this will destroy the fandom we love so much. (March 26, 2012; http://www.themarysue.com/50-shades-of-grey-and-the-twilight-pro-fic-phenomenon/#comment-476564778)

[1.6] For fans, then, the success of Fifty Shades raises concerns beyond those evidenced in mainstream media. The series is not simply badly written, poorly researched, misrepresentative of BDSM, and antiwoman; it is also not representative of fan fiction and is potentially damaging to fandom. These conversations have been largely ignored by the mainstream press and framed through the lens of fan exploitation.

2. Fan production and the gift economy

[2.1] The fannish gift economy may be used as a framework for understanding how fandom can function in opposition to a capitalist economy. Fan cultural production is perhaps most commonly thought of—at least in the wider media—in relation to fan fiction, but within fandom, it takes many forms. From fan fic to videos, meta to fan art, and icons to memes, the range and style of fannish work is as varied as the fans. Much academic work on fan production to date has drawn on Henry Jenkins's concept of textual poaching. Jenkins positions fans as active consumers of media products and challenges the existing stereotypes of fans as "cultural dupes, social misfits, and mindless consumers" (1992, 23). He further argues that fans "actively assert their mastery over the mass-produced texts which provide the raw materials for their own cultural productions and the basis for their social interactions" (23–24). Jenkins and other scholars of fandom (Bacon-Smith 1992; Baym 1998; Chibnall 1997) have made much of fan activity as resistant, but not everyone is convinced of this analysis. Christine Scodari and Jenna L. Felder (2000) suggest that some claims of resistance made in early examinations of fan fiction have been overstated, while others (Kaplan 2006; Parrish 2007) emphasize the role played by the communal nature of fandom. Melissa Gray (2010) writes,

[2.2] This is why fandom is so rewarding: the vast sharing of points of view and creativity that makes it our universe, belonging to the fans as well as the creators of the canon, with our own characters and settings and situations. I can no longer watch episodes the way TPTB [The Powers That Be] likely intended. I bring not only my unique experiences to my viewing, but also the wealth of fanon background material that I've absorbed over the years.

[2.3] The notion of fandom being the fans' universe speaks to this communal nature. Fans do not simply upload art, fic, or vids; they also beta read each other's work, correspond with readers and other writers in mailing lists and discussion forums, respond to challenge communities, upload fan art as bases for icons, create videos based on other fans' song requests, meet in conventions, and share advice on cosplaying, among other activities. These activities work to foster a sense of community within fandom. This allows those engaged in fannish production to bounce ideas off each other; it also allows them to work collaboratively to create stories, art, music, and vids. Seen this way, fan production becomes less about acts of resistance than a means of reinforcing community. In other words, it forms part of what Lewis Hyde (1983) refers to as the gift economy. Hyde suggests that gift economies are distinguishable from commodity culture as a result of their ability to establish a relationship between the person giving the gift and the person receiving it. This giving and receiving creates a communal bond founded on a sense of obligation and reciprocity (Scott 2010). Drawing on Hyde, Karen Hellekson (2009) argues that fandom can be seen as a gift economy, in that exchange in the fan community is made up of three elements related to the notion of gift: giving, receiving, and reciprocating. She argues that the notion of the gift is central to fan economy, not simply because "the general understanding is that if no money is exchanged, the copyright owners have no reason to sue because they retain exclusive rights to make money from their property" (114), but because the gifts themselves have value in the fannish community. They are designed to create and cement its social structure:

[2.4] Fans engage with their metatext by presenting gift artworks, by reciprocating these gifts in certain approved, fandom-specific ways, and by providing commentary about these gifts. Writer and reader create a shared dialogue that results in a feedback loop of gift exchange, whereby the gift of artwork or text is repetitively exchanged for the gift of reaction, which is itself exchanged, with the goal of creating and maintaining social solidarity. (115)

[2.5] Suzanne Scott (2009, ¶1.1) notes that "recent work on online gift economies has acknowledged the inability to engage with gift economies and commodity culture as disparate systems, as commodity culture begins selectively appropriating the gift economy's ethos for its own economic gain." This commodity culture is perhaps best exemplified through the case of FanLib, which sought to commodify fan fiction at a newly created archive. FanLib's creators targeted and e-mailed fan fic writers and encouraged them to upload fic to the site in exchange for prizes, participation in contests leading to e-publication, and attention from the producers of TV. As Hellekson (2009) and Jenkins (2007) both note, FanLib's persistent misreading of community as commodity alienated fans, illustrating that "attempts to encroach on the meaning of the gift and to perform a new kind of (commerce-based) transaction with fan-created items will not be tolerated" (Hellekson 2009, 117).

[2.6] However, it is not simply the binary of commodity culture and gift economy that work with (or against) each other. Milly Williamson argues that fan culture itself is influenced by two opposing sets of values that dominate the cultural field and that fans take positions in line with: cultural value based on the profit motive, and cultural production for its own sake—that is, the gift economy. This can lead to a split in fandom, with some fans influenced by economic principles and other influenced by "fandom-for-fandom's-sake" (Williamson 2005, 119). This split is epitomized in the controversy over James's Fifty Shades of Grey.

3. Fifty Shades of Grey and the ethics of pulling to publish

[3.1] Analyzing the reactions of fans to the publication and widespread success of the Fifty Shades series reveals two results: fans either applaud James for making the leap from fan fic to pro fic, or they criticize her for exploiting her fans and bringing fandom into disrepute. Both of these results are crucial to understanding the debates around fan labor and fan exploitation, but I will focus on the latter first. To do so, however, requires a deeper understanding of the genesis of the Fifty Shades trilogy.

[3.2] Fifty Shades of Grey and its sequels were originally written as an all-human alternate universe Twilight fan fiction called Master of the Universe, in which Edward Cullen was a rich CEO and Bella a college student. The fic was well known within Twilight fandom, and James, writing under the name Snowqueens Icedragon, had amassed her own fan following. Tish Beaty (2012), Fifty Shades' editor with The Writer's Coffee Shop, writes that by the time she got into the story, it had over 2,000 reviews on FanFiction.net, and Anne Jamison (2012) notes that although it is difficult to know for certain how many readers Master of the Universe had—the story moved from FanFiction.net to James's own Web site—it certainly had tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of readers. As Jane Litte (2012a) comments, "During the height of its popularity, an auction for the series raised $30,000. The author appeared on a fan fiction panel at the 2010 ComicCon and attended a three day conference in DC thrown by her fans" (note 4).

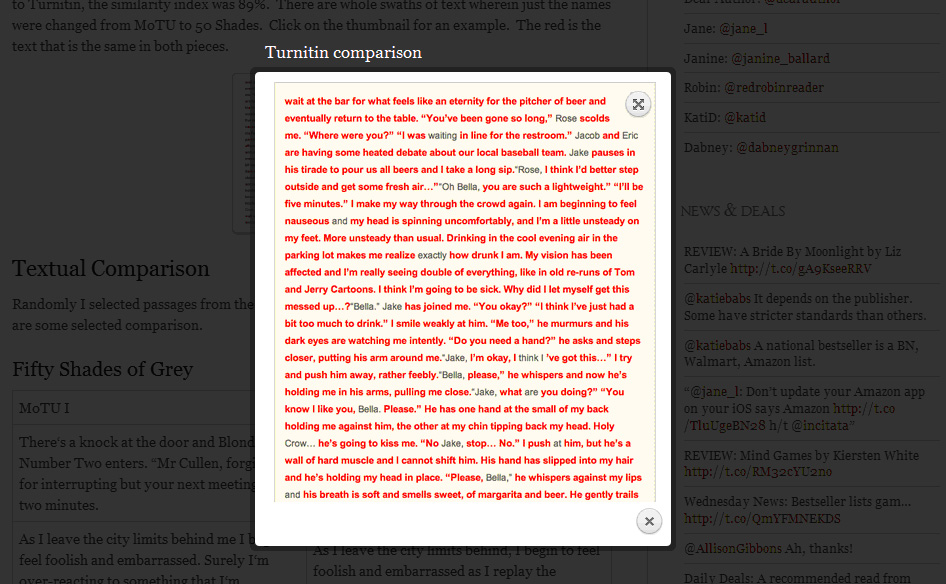

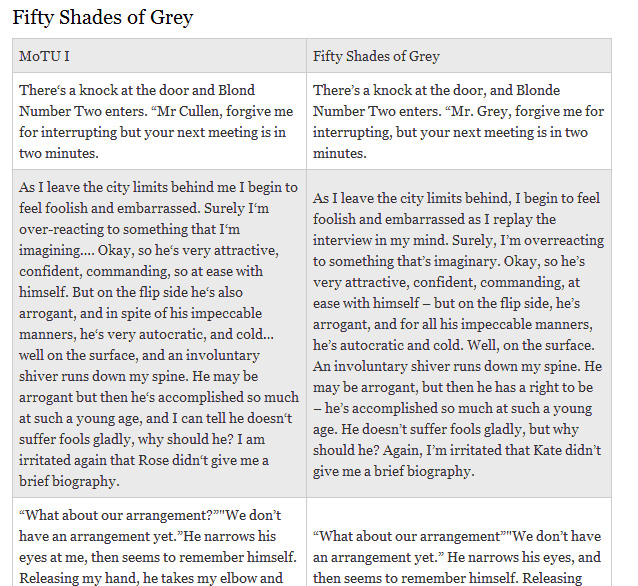

[3.3] When James contracted with The Writer's Coffee Shop to publish Master of the Universe as Fifty Shades of Grey, the work was pulled off-line and the Twilight-specific details removed. When the series was picked up by Vintage, its fan fiction origins were acknowledged but downplayed, with the publishing house issuing a statement declaring, "It is widely known that E. L. James began to capture a following as a writer shortly after she posted her second fan-fiction story. She subsequently took that story and rewrote the work, with new characters and situations. That was the beginning of the Fifty Shades trilogy" (quoted in Litte 2012b). Vintage had asserted that Fifty Shades was wholly original fiction, deviating substantially from the original fan fic, and Vintage stated that Fifty Shades and Master of the Universe were two distinct pieces of fiction. In March 2012, however, the Web site Dear Author (http://dearauthor.com/) carried out several comparisons on both pieces (figures 1 and 2), concluding, "Vintage says of MOTU and 50 Shades 'they were and are two distinctly separate pieces of work.' Turnitin (an internet-based plagiarism detection tool used by schools and universities) says they are 89% the same" (Litte 2012b). Fifty Shades of Grey was thus not substantively different from the fan fic it had originally been published as—a point that remains a bone of contention for James's critics.

Figure 1. Screen shot of Turnitin comparison of Fifty Shades of Grey and Master of the Universe posted on Dear Author Web site, March 13, 2012. [View larger image.]

Figure 2. Screen shot of comparison of Master of the Universe and Fifty Shades of Grey posted on Dear Author Web site, March 13, 2012. [View larger image.]

[3.4] The central issue in relation to fan exploitation and labor is that fan fic readers and reviewers did some of the work in creating Master of the Universe, but James took sole credit for its success. The role that the fannish community played in shaping what would become Fifty Shades of Grey, often discounted by the mainstream media, which asks how other fan fiction writers can become pro, is discussed and contested within fandom. As Has notes, "E. L. James has used and taken advantage of Twilight fandom, yes she's got her fans and supporters but overall she's left a huge wankfest on her road to publication…when you are writing a FF [fan fic], you are writing for that fandom and the universe which you love, no profit should be made from it because isn't that is [sic] taking advantage and using a fanbase to get a step up" (March 13, 2012; http://dearauthor.com/features/industry-news/master-of-the-universe-versus-fifty-shades-by-e-l-james-comparison/#comment-356698). Ros expresses a similar viewpoint:

[3.5] I cannot imagine ever taking one of my fan fics and rewriting it as original fiction. Not even the ones where I invented my own characters and plots, let alone the ones where I used characters from the source material and imagined them in new situations. Not because I am afraid that I would be breaking copyright—I'm pretty confident I could do a good enough job of the rewriting to avoid that—but because I would be breaking the trust of my fannish readers. Those were the people for whom I wrote, the people who loved the same fandoms I did and wanted more from them. They were the people who encouraged me and gave me feedback and let me do my learning and making mistakes without giving up on me. Those stories were freely offered and I was grateful for every single person who read them, commented on them or recommended them to others. In some way, those stories belong to my early readers as much as they belong to me. I do think that this is a huge difference between the way that fan fic works and the way that published fic works. Readers are much more involved in the process. Feedback comes with every chapter. Writing prompts are set and challenges posed by readers. And so on. It is an interactive process in a way that published writing is not. So if I were a Twilight fan who had read MOTU, I would be feeling seriously betrayed by the author. (March 13, 2013; http://dearauthor.com/features/industry-news/master-of-the-universe-versus-fifty-shades-by-e-l-james-comparison/#comment-356702)

[3.6] Sarah Wanenchak (2012) notes that "given that fannish works are driven primarily by collective love for a particular media property, there is a sense among most members of fandom as a whole that the seeking of monetary gain from fannish works is not only legally questionable but sullies the respect that fans ideally have for the object of their fandom." She suggests that this collaborative process—the production of work, its consumption, the production of a response, its consumption, the production of new work—is the point at which copyright issues intersect with the ethics of fan culture and necessitate the consideration of prosumption. Discussing prosumption—that is, the simultaneous role of being a producer of what one consumes—George Ritzer and Nathan Jurgensen (2010) argue that Web 2.0 facilitates the process through such examples as Wikipedia, Facebook, YouTube, Flickr, and the blogosphere. With the advent of these new media technologies and the way in which they affect fannish engagement with objects of fandom, producers are becoming more reliant on fan labor to build their brand and increase their product's longevity, as Alexis Lothian (2009) points out:

[3.7] In recent years, media producers have explicitly sought to solicit fan participation as labor for their profits in the form of user-generated content that helps build their brand. Many fans perceive these developments as a desirable legitimation of fan work, but they can also be understood as an inversion in the direction of fannish theft. Rather than fans stealing commodified culture to make works for their own purposes, capital steals their labor—as, we might consider, it stole ideas from the cultural commons and fenced them off in the first place—to add to its surplus. (135)

[3.8] Fifty Shades complicates the concept of prosumption, however, as James "built a following within a community founded in part on the explicit rejection of monetary gain in favor of fannish love, and then used that community and the work it helped her to produce in order to make a name—and a fair amount of money—in mainstream publishing" (Wanenchak 2012). James thus straddles the line between producer and fan, stealing from commodified culture to create Master of the Universe while stealing from fandom to make a success of Fifty Shades. The question of whether James's fans would have been so involved in supporting and reviewing her work if they were aware that their efforts would result in her profit—although ultimately unanswerable—is nevertheless a valid one, and I would suggest that these debates suggest a subtle change in the relationship between fan and producer. From being in a position of cultural marginality where they poach from texts, fans are now the ones potentially being poached from (Andrejevic 2008; Milner 2009). Milner (2009) notes that as active audiences become more prevalent, producers of media texts are fast recognizing the value of courting niche groups of prosumers. Julie Levin Russo (2009) details how Video Maker Toolkit invited fans to be part of the Battlestar Galactica TV reboot (2004–9) by making a 4-minute film, the best of which would be aired on television—in return for fans giving up their rights to the vids. J. J. Abrams, creator of Alias (2001–6) and Lost (2004–10), has commented that he regularly reads Internet fan message boards; he claims that listening to real-time audience feedback gives his shows some of the characteristics of a live play (Andrejevic 2008). Similarly, James's reading of reviews and engaging in a dialogue with fans creates an author/editor dynamic. Andrejevic (2008, 26) suggests that as a result of this more active, critical approach to viewing, "fan culture is at long last being deliberately and openly embraced by producers thanks in part to the ability of the internet not just to unite far-flung viewers but to make the fruits of their labor readily accessible to the mainstream—and to producers themselves."

[3.9] Andrejevic (2008) further suggests that the promise of accountability, which forums like Twilighted (http://twilighted.net/) and FanFiction.net (https://www.fanfiction.net/) provide, also works to foster identification on the part of audiences with the viewpoint of the producers. Similarly, James's involvement in fandom provided her with the opportunity to use fans' knowledge while also causing fans to identify her as one of them. Tish Beaty notes that the Twilighted forum on which James posted Master of the Universe is where James built her original fan base. She writes, "The Bunker Babes are a group of Fifty Shades fans that supported and backed James no matter what direction she took the story. They promoted Fifty Shades all over Twitter and the fan fiction communities. They were her sounding board and cheer squad, and were a force to be reckoned with" (2012, 300). The role of the Bunker Babes here aligns with that of fans participating in a gift economy. As Hellekson notes, "In terms of the discourse of gift culture, fandom might best be understood as part of what is traditionally the women's sphere: the social, rather than the economic" (2009, 116; emphasis added). By promoting and backing James, the Bunker Babes were also policing the boundaries of fandom and its subjects, with their motivations being "ultimately about protecting, rather than controlling, the ideological diversity of fannish responses to the text" (Scott 2009, ¶3.2).

[3.10] Reading the Bunker Babes' support in terms of prosumption, however, results in a different understanding of the relationship between them as fans and James as a producer. As Jenkins (2006, 134) notes of the delicate relationship between the producer and productive consumer in the age of the active audience, "The media industry is increasingly dependent on active and committed consumers to spread the word about valued properties in an overcrowded media marketplace, and in some cases they are seeking ways to channel the creative output of media fans to lower their production costs."

[3.11] Fandom's position in Web 2.0 and its use of new media technologies means that publishers working with pulled-to-publish fic already have a source of fan labor that they can use to build their brand and increase their product's longevity. However, "enlisting unpaid customers to co-produce the products and services, which are converted to money in the market…corresponds to the expropriation of surplus value from consumer labor" (Zwick, Bonsu, and Aron 2008, 180). James's use of fannish resources, coupled with her failure to acknowledge that support, is, for some fans, an exploitation of fandom. As AlwaysLucky1 notes,

[3.12] I only bought the book because I did [read] MOTU when it was original. I paid to buy Fifty because I felt I was supporting a fan fiction "friend." She didn't "force" me to buy her book, as you put it. But, I am disappointed that she didn't somehow acknowledge her fellow fan fictioners in the Fifty acknowledgement…Here's the thing. She's a writer. As she was writing the fan fic…people were reviewing it. That's why her publishing company paid attention to her. There were so many reviews on the story already. She was getting alot of positive feedback on something so racy. As she posted a new chapter every week. We reviewed every week. As much as she fed us, we fed her with our comments AND suggestions in how far she could or couldn't take the story. (May 29, 2012; http://www.mediabistro.com/galleycat/fifty-shades-of-grey-wayback-machine_b49124#comment-540658007)

[3.13] However, some fans, such as Debra Conway, have applauded James for turning fan fiction into successful original fiction:

[3.14] Do you honestly think the "captive audience" of Twilight is the same one buying Fifty Shades of Gray? Not unless they've found Twilight fan fic. I'm laughing out loud. And that she somehow cheated her fan fic readers, somehow forcing them to buy her books?…Ms. James wrote an original story—the characters themselves and their experiences were original. She used names from her favorite book and put her story online for free for a while. She still owns the story. Period. James is now a published, successful author. Her book busted the boundaries for the acceptance of what women read and is a phenomenon. I applaud her. You should too. (May 28, 2012; http://www.mediabistro.com/galleycat/fifty-shades-of-grey-wayback-machine_b49124#comment-540641358)

[3.15] The possibility of fans monetizing their own modes of production is posed by some scholars as an alternate form of preemptive protection. Abigail De Kosnik (2009, 123) argues that the "rewards of participating in a commercial market…might be just as attractive as the rewards of participating in a community's gift culture" and puts forth the idea that fans initiating the commercialization of fan production "gifts" insiders, rather than outsiders, the right to profit. Scott (2009, ¶1.3) suggests that De Kosnik's model "clearly identifies the value of fan labor and encourages fans to develop a competitive model to profit from their labors of love rather than continuing to feed an industrial promotional machine." I examine this next.

4. Twilight fan art on Redbubble and Etsy

[4.1] John Fiske (1992) notes that while most fan producers gain considerable prestige in the fan community, with a few exceptions, they earn no money for their work; the main historical exception appears to have been fan artists who sell their paintings and sketches at conventions and fan auctions. The increase in commerce sites such as Redbubble (http://www.redbubble.com/) and Etsy (http://www.etsy.com/), however, has resulted in what Brigid Cherry calls "an extremely commercial niche for entrepreneurial fans" who sell, among other things, T-shirts, prints of artwork, jewelry, shoes, bags, notebooks, yarn, and patterns (2011, 137). Cherry's analysis of vampire fandom knitters on Ravelry (https://www.ravelry.com/) demonstrates the ways in which fan production can be commodified, as members are able to sell patterns in the marketplace, with costs ranging from $3 to $12. However the arguments that Cherry makes can also be applied to other fan-produced objects. Just as ads often appear in vampire fan knitting forums, and just as yarns produced by a specific dyer develop a cult status, becoming highly sought after in their own right, so too do specific producers of fan-made jewelry or T-shirts become well known within their specific fandoms. Furthermore, sites like Teefury (http://www.teefury.com/) and Qwertee (http://www.qwertee.com/), which offer fan-designed T-shirts for $8, feature interviews with the artists and encourage a cult status by both limiting the sale of T-shirts to a 24-hour period and encouraging users to vote for their favorite designs for potential sale again in the future. This cult status is dependent not only on the quality of the products but also on the shared love of the fannish text between producer and consumer. This problematizes the market/nonmarket dichotomy that appears in accounts of fandom as a gift economy and in fandom's reaction to pulled-to-publish fan fic.

[4.2] The ethical prohibition against selling work in such a way as to exploit fans is further problematized when taking into account these art-commerce sites. Historically, fanzines were sold at cost rather than for profit, a result of the ethical prohibition against profiting from the object of fandom. The argument could similarly be made that the sale of fan-produced objects like jewelry is acceptable because the items cost money to make: electrons are perceived as free, but creating a Harry Potter–themed scarf requires buying yarn and equipment. It is possible that any money made selling these items only covers the cost to produce them, thus positioning these products similarly to fanzines. The rise of sites like Redbubble problematizes this, however, because the cost of producing the item falls on Redbubble itself rather than on the fan producer. On Redbubble, artists upload designs and choose which items they would like those designs applied to. An artist might create a Doctor Who image using digital art packages, upload the design to the Web site, and specify that she would like it to be made available on T-shirts, bags, and phone cases. There is therefore no cost to the fan producer in creating the piece of work; instead, Redbubble takes a percentage of the sale cost. In that respect, posting work to Redbubble is closer to fan fiction than physical fan art. Yet the sale of fannish goods on Redbubble remains acceptable among fans, whereas pulling fan fic to publish it professionally is not.

[4.3] Sal M. Humphreys (2008) suggests that we should consider "hybrid market environments where there is no such clear distinction between the social and commercial economies—where instead they co-exist in the same space, and where some people occupy different positions over time within the same markets." Humphreys's analysis of the Ravelry discussion boards suggests that the social matters as much as the commercial and the financial, and indeed in many ways influences both production and consumption. Similarly, Etsy's community forums function to provide a social space where Twilight fans can discuss the text while sharing links to the Twilight items they produce and sell. The "Show me your favorite Twilight item" thread in the Twilight Ladies group contains both discussion of favorite characters (with Edward and Jacob featuring strongly) and links to items to buy. Members of the group thus combine fannish interaction with commercial interaction, often with no line dividing the two.

Figure 3. Mrs. Edward Cullen ring by danandesigns, sold on Etsy. [View larger image.]

[4.4] This fannish/commercial interaction also takes place on sites that are more commonly thought of in relation to fan fic. The twilight_crafts LiveJournal community, for example, encourages sales posts and stipulates that all items must be related to Twilight (note 5). Many users of the community who also sell Twilight-themed items on Etsy offer free shipping to buyers directed to their shop by the LiveJournal site, thus recognizing the fannish gift economy while commodifying fan labor. As Humphreys (2008) notes, "It's possible to identify people who both give away and sell their content. People negotiate and occupy positions within social, reputational, gifting, and commercial economies—sometimes simultaneously, sometimes sequentially."

[4.5] The rise of e-publishing is of particular interest in relation to these producers, as is its role in the success of the Fifty Shades series. J'Aimee Brooker (2012) notes that e-publishing gives writers much more control over their work in terms of content, distribution, marketing, and pricing. She writes that the financial benefits of e-publishing are also markedly higher than those of traditional publishing: "Self-published authors listing their product with Amazon are privy to a royalties rate of 70% compared to 15–20% of royalties offered by traditional publishing houses." Penguin's 2012 acquisition of the self-publishing platform Author Solutions (https://www.authorsolutions.com/) also suggests that traditional publishers are becoming aware of the opportunities afforded by self-publishing platforms. At the time of this writing, Amazon had just announced that it was launching a new platform, Kindle Worlds, where fan fic writers can upload and sell their work. Kindle Worlds enables companies such as Warner Bros. to license their copyrighted material and allows fans to publish their fan fic as e-books for the Kindle e-reader (https://kindleworlds.amazon.com/). Royalties will be paid to both the original author and the fan fiction writer. Although full details remain to be published about how this will work, fans may be able to publish their work on Kindle Worlds while also posting it on free sites such as FanFiction.net, thus negotiating and occupying a range of positions (note 6).

[4.6] Not all fan entrepreneurs give away and sell their content, however. Redbubble, although containing forums similar to Etsy's, is much more commercial in appearance. Whereas Etsy forges its identity as a site for handcrafters, Redbubble markets itself as a site for independent artists. Cornel Sandvoss (2005) contends that while fandom per se is not necessarily gendered, specific fan activities, interests, and communities are often marked as feminine or masculine. The differences between the Etsy and Redbubble sites appear to reinforce that gendered difference—and the ways that fan labor is commodified on each of them.

Figure 4. Superiorgraphix's "Bite Me Edward" T-shirt on Redbubble. [View larger image.]

[4.7] Craig Norris and Jason Bainbridge (2009) note in their study of cosplayers that the wearing of "t-shirts or caps with logos such as the Autobot or Decepticon insignias from the Transformers [is] connected to a more general otaku experience, marking out people as fans of a certain manga/anime property." Similarly, wearing T-shirts featuring logos such as the team emblem from Gatchman or the NERV symbol from Neon Genesis Evangelion marks the wearer as a member of fandom, although through a play with identity where others have to be able to recognize the design to recognize the property being emulated. This consumption as classification (Holt 1995) is a fruitful way to understand fan consumption of art, clothing, and jewelry. Unlike the purchase of a book of pulled-to-publish fan fiction, fannish-themed clothing and accessories mark the wearer as belonging to a specific group or community. Ruth Deller and Clarissa Smith (2013, 937), in an analysis of reader responses to Fifty Shades of Grey, note that "the ebook format and the paperback books' understated cover designs…were cited by several of our readers as a key appeal of the novels, either for themselves or others, because they 'disguised' the books' content." Among the responses given by readers were the following:

[4.8] You can read it on your kindle and nobody knows that you're reading it! The classy covers also help because they don't look like genre fiction, more like literary fiction. (Reader 5)

[The covers are] Genius. If you know what the images represent, then it's very cheeky, a subtle reminder of all their "kinky fuckery." But if you don't, it's completely innocuous, and not cheesy. (Reader 10)

They are anonymous, fit quite well with books but not too embarrassing on train! (Reader 47) (quoted in Deller and Smith 2013, 937–38)

[4.9] These responses suggest that a Fifty Shades community did not exist among readers of the books; there were no moments of recognition between passengers on the subway, as there would between Neon Genesis Evangelion fans—although Deller and Smith do point out the contradiction that lies at the heart of the anonymizing covers and their recognizability. There are, however, Fifty Shades–themed items on Etsy and Redbubble, suggesting another contradiction between readers consuming the books anonymously on Kindle and readers consuming fan-made items.

Figure 5. FrillsByStudioK, Fifty Shades of Grey party signs on Etsy. [View larger image.]

Figure 6. JcDesign, "Keep calm and stow your twitchy palm" T-shirt on Redbubble. [View larger image.]

[4.10] The alternative consumption objects made and sold on Etsy and Redbubble have a similar amount of prestige attached to them as to the more traditional, resistive forms of consumption objects such as fan fic. Unlike fan fic, however, in which fans express their love of a text, fans are expressing a love of a brand in the consumption of fan-themed clothing and accessories. This difference accounts for the differing reactions to pulled-to-publish fan fic and fan art sold online. Pulled-to-publish fan fic, unless its origins become part of the metatext surrounding its publication, loses the identification with fandom that it had as freely available fan fic. This distancing from the source object causes some of the tension evident within fandom when authors profit from a formerly free piece of work. It is not—or not simply—the fact that it had been published for free online that fans take issue with. Nor is it the fact that the author is profiting from another writer's work. Rather it is the refutation of the fannish space that comes when fan fic is published as original fic that becomes problematic. This can be contrasted to the reinforcing of fandom and community that comes from buying and wearing a piece of clothing or jewelry. In discussing Liverpool fans, Brendan Richardson (2011) notes that

[4.11] the manner in which goods are used, and the prestige attached to them, varies in accordance with the need to maintain the sacredness of fan identity and experience. A clear distance must be established to separate sacred fan identity from the profane marketplace. In the case of members of the "Real Reds" Liverpool fan community, co-production that relies excessively on consumption of official merchandise is regarded as far less meaningful than co-production that utilises alternative consumption objects, such as home made banners, as part of the process of production.

[4.12] Richardson (2011) suggests that to these fans, the market is seen as something incapable of delivering unique experience. This sentiment applies equally to The Writer's Coffee Shop's appropriation of Master of the Universe and its subsequent publication as the Fifty Shades series: it becomes simply one more erotic novel rather than an important contribution to Twilight fandom.

[4.13] The market of The Writer's Coffee Shop or the market of the football premiere league are thus different than the idealized fan marketplaces of Ravelry and Etsy. Cherry (2011) suggests that these sites exist outside of the industries that see fans as an exploitable market, but no such space seems to exist for fan fic writers (note 7). Where does this leave those authors who pull to publish, as well as the fans who see that as a betrayal? Aja Romano (2012) writes,

[4.14] Fans are extremely divided as to whether publishing fan fic as original fic is a natural way to capitalize on a well-deserved fan following, or whether it's a betrayal of the principles of free exchange that keeps fandom healthy and independent. It's probably somewhere in the middle. Lots of fan fic authors have converted their fandom audience into a wider audience for their original writing. And even if they didn't profit directly from a single fic with the names and settings changed, they still profited immensely from fandom experience. Fandom gave them writing workshops, networking skills, critiquing experience, and maybe even professional connections. All of that is a form of profit. And then there is actual published fan fiction, such as movie adaptations, branch-off comic universes, and franchise tie-ins. The truth is that the line between fan fiction and commercial fiction has been blurry for centuries, and neither original fiction nor fan fiction are in any danger of vanishing as a result of the overlap.

[4.15] Romano's final point—that neither pro fic nor fan fic is in danger of disappearing—although valid, misses the point of fan arguments against pulling to publish. Twilight fans felt betrayed at James's earning millions of pounds from their communal input, but they were also concerned at the impact that the publication of a not very well-written work would have on fandom. Many fans were at pains to point out that good fan fic does exist and that fan fic writers are not lazy, unimaginative, or unable to come up with their own original fiction.

5. Final thoughts on the self-commodification of fandom

[5.1] The positioning of fans as resistant, which has dominated much of the field of fan studies, has tended to be interpreted as a form of ideology-based consumer resistance. As Richardson (2011) outlines, the possibility that the motives for fan resistance are grounded in the same root causes that inspire fan commitment and loyalty has not necessarily been fully explored. Nicholas Abercrombie and Brian Longhurst (1998) have applied the term "petty producers" to those who have moved from being enthusiasts to becoming full-time producers, thus placing fans as producers and fans as consumers at opposing ends of their incorporation/resistance paradigm. I find this too simplistic. Abercrombie and Longhurst (1998, 140) suggest that as the enthusiast moves out of enthusiasm toward being a petty producer, "he/she is returned more to general capitalist social relations; as producers, they are as much at the mercy of structural forces as the consumers at the other end of the continuum." Constructing producers and consumers or commodity culture and gift economies in binary terms, however, is problematic. Garry Crawford (2004) suggests that it is preferable to view modern fan culture as an adaptable and dynamic social "career," arguing that individuals in sports fandom increasingly draw on sports for both identity construction and opportunities for social performance. As more traditional sources of community identity decline, the sense of community offered by contemporary sports becomes increasingly important and is increasingly commodified. Richard Barbrook (2005) argues that "money-commodity and gift relations are not just in conflict with each other, but also co-exist in symbiosis," even though each model "threaten[s] to supplant the other." Commodity economies and gift economies are thus already enmeshed. Paul Booth (2010, 131) refers to this as a digi-gratis economy and suggests that it "assumes that both [market and gift] economies are crucial for the functioning of a complete economic system, and work together, always. Fans create 'gifts' out of the products they purchase in the market economy, and the market caters to the fan culture by offering free services that fans can interpret as gifts."

[5.2] This analysis is still largely problematic because it means engaging in a capitalist system, as Cornel Sandvoss (2011) notes,

[5.3] Enthusiasts in any realm of cultural production are thus confronted with the inescapable logic of the capitalist system: fans whose textual productivity holds commercial value to third parties, yet wish to opt out of the system of monetary exchange and preserve their fandom as non-commercial space, inevitably open themselves to the exploitative utilisation of their productivity by others. Only if they subscribe to the principles of capitalist exchange in the first instance, are fans able to avoid such exploitation, yet thereby erode the pleasures of the fan-object of fandom relationship based on control and appropriation of fan texts that operate outside such principles and that cannot accommodate the material separation between fan and fan object manifested through monetary exchanges. (54)

[5.4] This self-commodification of fan labor is not necessarily a good thing when fan labor is already exploited. De Kosnik (2009) asserts that the commercialization of fan practice might actually be empowering for female fan authors, but this suggests that fan production is only legitimate when viewed through a capitalist lens. Not all fans wish to become media producers, just as not all fans are working in resistance to corporations when writing fan fiction.

[5.5] Writing about the Battlestar Galactica Video Maker contest, Will Brooker suggests that the largely female practice of fan fic remains resolutely separate from the new dynamic of producer-controlled fan content. He also notes, however, that

[5.6] the fan fiction community now has an urgent choice to make: whether its separate sphere should tool up and monetize its practice before someone else does; or stubbornly float free, refusing to engage with mainstream structures, sticking to its own currency and maintaining an older notion of "fandom" at a time when the word's meaning may have shifted beyond its previous definitions. (2014)

[5.7] The rise of pulled-to-publish publishing houses, e-publishing, and initiatives like Amazon's Kindle Worlds appears to be forcing some fan fic writers to monetize their practices, and James's success with Fifty Shades of Grey clearly demonstrates that fan fic writers can make a lot of money by adapting their works. The difference in attitudes toward the sale of fan art and the sale of fan fic is still prevalent within fandom, however, and these new developments are likely to continue the debate. Certainly the cost of producing fan-made items such as jewelry plays a role in the different attitudes between the sale of fan art and the sale of fan fic, although the cost of labor in making scarves, jewelry, and artwork may be equally as unpaid as the cost of producing fiction. However, a larger difference comes in the transparency offered by the sale of fan art. Fan fic is published and freely available online; to pull it only to republish it as original fiction suggests an element of dishonesty on the part of the author. In contrast, fan art—particularly in the form of jewelry or clothing—is rarely offered for free elsewhere first. Further, the role that the fannish community plays in the creation of fan fic is more defined than in the creation of fan art. Although fan artists may post their pictures and ask for advice or feedback, this is much less common than fan fic writers posting works in progress or using beta readers to review their work. For one person to profit from the work of a community, as James did with Fifty Shades, can be seen far more clearly as exploitation.

[5.8] Finally, I wish to return to the idea of pulled-to-publish fan fic being a refutation of a fannish space; I question whether this raises larger issues than simply the commodification of fandom. Pulled-to-publish fan fic loses the identification with fandom that it had as freely available fan fic. Fifty Shades of Grey, Sylvain Reynard's Gabriel's Inferno (2012), Christina Lauren's Beautiful Bastard (2013), and myriad other pulled-to-publish works are no longer tied to the fannish objects that inspired them. Furthermore, the adoption of pen names and the removal of the text's fannish history from writers' Web sites increase the divide between the fannish and the professional writer. If we accept the idea of fandom as a gift economy, as well as the notion that fandom involves some level of community, the ability for one person to profit from a potentially multiauthored piece of work is indeed problematic. This has wider implications for fandom than producers exploiting fan labor.