1. Introduction

[1.1] In a November 2011 blog post titled "From Killer Moth to Killing Joke: Batgirl, A Life in Pictures" (http://mindlessones.com/2011/11/09/from-killer-moth-to-killing-joke-batgirl-a-life-in-pictures/), media scholar Will Brooker expressed his frustration with Batgirl: "I wanted to like Barbara [Gordon]. I just wasn't getting much to work with." He went on to detail a series of tropes—self-conscious first-person narration, forgettable fights with D-list villains, the questionable decision to wear high heels to fight crime—that make it easy to understand why a comic book reader might finish a superheroine comic book feeling a bit like Batgirl at the end of a mission, "wondering if she can carry on, and if so, when, and why she does all this after all."

[1.2] Brooker closed his annotated visual history with a promise to readers: "We are building a better Batgirl. Look out for her." The "we" is central, a reflection and extension of comics' collaborative ethos. The outcome of this pledge is My So-Called Secret Identity, written by Brooker and featuring art by Sarah Zaidan and Suze Shore (note 1). Brooker describes the project as "an experiment: a non-commercial project to prompt discussion and maybe suggest a different way of doing things, in terms of approach, aesthetic and practice." Though My So-Called Secret Identity remains intertextually indebted to Batgirl, its "different way of doing things" suggests that fans' transformative impulse might move beyond the text itself to comment on industrial inequities and the gendered nature of comic book content and culture.

[1.3] Thus, while the project suggests new possibilities for collaborative transformative works, this difference is also demographic, establishing a network of predominantly female creators and commentators. Three of these commentators, Carlen Lavigne, Kate Roddy, and Suzanne Scott, composed the questions below. All three interviewers had access to scripts for issues 1–5 and early concept and character art (http://www.flickr.com/photos/drwillbrooker/sets/72157629358191516/), and all offered feedback on the project.

[1.4] The interview has been edited for clarity, but it is important to note that this exchange is part of an ongoing conversation that began in the comments section of Brooker's initial post, and has continued via e-mail.

2. Meet "Team Cat"

[2.1] Q: Briefly introduce yourselves and explain how you became involved in this project. How have your past experiences in comics fandom or other aspects of your background affected your contributions to the work so far?

[2.2] Sarah Zaidan: During my first year of PhD study, Will Brooker's Batman Unmasked was an instrumental text in the formation of my thesis. In what I like to think of as a dramatic twist of fate, later that year, I was presented with my second supervisor, Will Brooker, and the rest is history! Over the next 3 years, I completed a prototype of the interactive software that was my thesis, received my doctorate and finally had free time to work on Project Cat.

[2.3] My experiences with comic book fandom have certainly made me familiar with the tropes and conventions of the superhero genre, as has my research. I've also been a gigantic Batman fan for two decades, and given My So-Called Secret Identity's start, it's been a wonderful experience for me to see how Cat and her world have evolved beyond their initial incarnations into fully realized characters and places. Through interactions with my fellow sequential art majors, online comics fandom, and a lot of female gamers and role-players, I can see that Cat is a character the genre has a need for, and that's another reason I really believe in this project and am so excited to be a part of it.

[2.4] Will Brooker: I grew up reading comics in the 1970s, and my first experience of Batman was a hybrid one: Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams's contemporary, gritty comic books, and reruns of the Adam West 1960s TV show. Many fans, authors, and producers regard these two Batmen as binary opposites, a camp aberration that was effectively corrected by the tough comic book reboot, but I enjoyed them both as different parts of the same picture, and that attitude has stayed with me. I drifted away from comics during my early teens and was won back by the mid- to late 1980s graphic novel boom. By the mid-1990s I'd enrolled on my PhD, which became the book Batman Unmasked.

[2.5] I read very widely in the mid- to late 1980s. So alongside Watchmen and Dark Knight, I read The Feminine Mystique, The Second Sex, feminist novels by Zoe Fairbairns and Marge Piercy, and particularly feminist science fiction, from Herland to Joanna Russ's The Female Man. I became interested in gay rights in the context of the UK's homophobic Section 28, and my involvement in comics fan culture during the early to mid-1990s intersected with my increasing participation in feminist and queer communities—most notably in my own (largely forgotten) edited fanzine, Deviant Glam, which was basically about superheroes and trans* identity.

[2.6] I think it was because I lost touch with those communities and for various reasons got a little locked into the role expected of me as a professional man (and manager) that I became, in every sense, more of a dick. This dialogue, organized by Henry Jenkins (http://henryjenkins.org/2011/10/acafandom_and_beyond_will_broo_1.html) helped me realize that in dissing squeeing and other "feminine" fan expression, I was really still trying to distance myself from and disavow an aspect of myself. The Batgirl articles from late 2011 come from a more honest position for me, as does (I hope) the So-Called Identity project.

[2.7] Suze Shore: Looking back, I think I've always felt the most accurate and efficient way for me to express myself is through a combination of both words and pictures. This mind-set started fleshing itself out during a one-year certificate of illustration at Algonquin College, where it was made clear to me that sequential art was both a valid and effective method of expression and communication. In the past couple of years I've been creating comics, both sporadic autobiographical shorts and working other people's narratives.

[2.8] My work on MSCSI began when Will Brooker approached me about drawing up some character designs for his project. What struck me immediately was his refreshing treatment of female characters; I've been increasingly concerned with the treatment of gender—specifically women—in comics and the general media, and Will's female characters are wonderfully real in their personalities and appearance. Women in comics, specifically the superhero genre, seem to be under constant threat of being presented as accessories rather than people. Cat and the cast of the So-Called Identity project are a definite stand against that.

[2.9] Will Brooker: When I saw this strip online, I knew Suze was someone I needed to approach about the Batgirl project (as it was then), and our correspondence started off the back of that.

Figure 1. "Arkham Outfitters," by Suze Shore (http://imgur.com/TdvKZ). [View larger image.]

3. Building a better Batverse

[3.1] Q: This project began as an attempt to build a better Batgirl, and there are notable intertextual and iconic ties to that property, such as Cat's costume and inner monologue, which evoke and subtly comment on Batgirl tropes. How much influence did Batgirl (or the Batman franchise broadly) have on the narrative and aesthetic choices here? How transformative is this text, and why?

[3.2] Will Brooker: I had initially just planned to create a scrapbook of script extracts, character sketches, synopses, and covers for a hypothetical reboot project—a sort of alternate history Batgirl, from another (better) version of the 1990s DCU, to prompt discussion and suggest different ways of doing things.

[3.3] Once I started talking to artists, I realized that this could really be done as a complete story, and by the time I actually wrote the script for the first episode, I'd made the fundamental decision to change all the characters' names and key details to move them away from the DC originals. So it became a story about analogues, in the same way as Watchmen's Rorschach and Comedian are essentially The Question and Peacemaker, and The Authority's Apollo and Midnighter are a version of Superman and Batman. I progressively changed the characters' appearances to distinguish them from the originals too. The name Cat just fell neatly into my lap—it sounds like a chick-lit novel rather than a superhero comic (http://www.amazon.co.uk/Cat-Freya-North/dp/0099278359), it evokes Catwoman (and Katie) as well as Batgirl, and it enabled a strand through the story about Catherine Abigail Daniels—I had imagined Barbara Gordon must be Irish American—finding a name she's comfortable with. "Cat" is not so much a secret identity as an expression of who she is.

[3.4] I would say that So-Called Secret Identity is both its own independent story and a commentary on the Batman mythos. One interesting turning point for me was a conversation I had online with the young adult fiction author Karen Healey. I told her what I envisioned happening to Dahlia and Cat by the end of the story arc, and she was horrified. I suddenly realized I was still trapped by the conventions of mainstream superhero storytelling; I had unconsciously internalized the idea that bad things have to happen to strong women in comics, for no reason except to shock the reader and enable a victim to become the tough survivor archetype. It was liberating to realize that people didn't actually have to be tortured or die—that things could be different—and it really brought it home to me just how powerful the dominant conventions of the genre are, that I had felt bound to follow that route without even realizing it.

[3.5] Suze Shore: My unfamiliarity with most of the Batgirl/Batman franchise has resulted in very little influence on my design work for MSCSI. My number one influence in drawing/outfitting Cat and others has been a yearning for realism and practicality. I can't remember the first female superhero I saw in the media, but I can more or less guarantee that she was doing her fighting in heels. One of the goals in a lead female like Cat is to introduce someone not only powerful, but also based in reality. So for Cat I started at the practical boots and went from there: what would a regular girl wear to run around in at night? What would she own and be able to move comfortably in?

[3.6] Sarah Zaidan: Batman has been a presence in my life in one form or another since I was given a tape of the 1969 Batman with Robin The Boy Wonder animated series when I was 5. The episode "From Catwoman with Love" stands out in my mind as the first time I'd ever seen Batgirl, who also put in an appearance as Barbara Gordon. Full of cat-related puns though the episode was, my young imagination was captured by the first female superhero I'd ever seen, who saved the day when her male counterparts were trapped by one of Catwoman's schemes. When I was older and began building my library of comics and graphic novels and came across The Killing Joke (1988), billed as essential Batman reading, I was horrified. I consider that the point where I truly became aware of how horrible things persist in happening to female superheroes and strong female characters in general. So when Will told me he'd made the decision to turn MSCSI into an original work with its own setting and characters, I was thrilled that I'd be a part of a project that was breaking away from tropes.

[3.7] My initial images for MSCSI are very much in keeping with the Batman: The Animated Series style, because at the time it was still a Batgirl story. Since the work has evolved, I'm incorporating a lot more of my own art style while bringing in elements of Suze's.

Figure 2. "Cat," by Sarah Zaidan (http://www.flickr.com/photos/drwillbrooker/6892239530/in/set-72157629358191516/lightbox/). [View larger image.]

[3.8] Q: Urbanite (the script's Batman analogue) is derided by the protagonist, Cat, for his authoritarianism and distrust of women. Are these accusations that you think can be leveled at Batman himself (or at least certain versions of him) and/or other mainstream comic heroes?

[3.9] Will Brooker: I think these accusations can be leveled at certain interpretations of Batman. Urbanite is in part a critique and parody of the so-called purist fan view of Batman as a badass, cold, and committed one-man army, and the representations of the character that fit that particular reading.

[3.10] There's also an element of social critique as Urbanite is a rich man's fad of crime fighting, rather than a genuine and concerted attempt to deal with crime and its causes; by implication, Batman could be seen as Bruce Wayne's expensive hobby.

[3.11] This is only a mockery and attack on one aspect of the Batman mosaic, though it's been a dominant aspect since the early 1970s. I remain very fond of Batman as a cultural icon—although I don't personally love all his incarnations equally—and I think that actually comes across in the mockery of Urbanite. The more I studied and reread Batgirl's stories, though—especially Killing Joke and its aftermath—the more I started to get really annoyed with Batman's treatment of her as a pawn in his bigger game against Joker (and vice versa, but we expect that kind of callous cruelty from a villain).

[3.12] Sarah Zaidan: With Urbanite, as with Batman, I tend to read him as not being fully aware of just how damaging a view like that is to himself and others. I think Batman can be cool, ridiculous, and tragic at the same time. This limited view is something I do see in other masculine heroes in mainstream comics, although perhaps not to the obsessive levels Batman takes it to.

4. On gender and comic book conventions

[4.1] Q: Were there certain superhero comic styles or conventions you particularly wanted to avoid in your representation of Cat and her world? Did any elements prove inescapable?

[4.2] Will Brooker: A very early correspondence invited Suze to draw Cat in "a costume made of stuff a 23-year-old with fashion-student friends could put together—so, a customized ski mask, black boots, big belt, a little rucksack—things she could patch together on her own, not a fully developed costume—and something practical, chunky, loaded with accessories, rather than skintight, sexy and revealing." So we were on the same page from the start.

[4.3] An early character document describes Cat as "attractive, physically fit to a college sports level but above all, incredibly smart." I certainly didn't want her to have the conventional superheroine physique or to adopt conventional superheroine poses. She is slim, but later developments give us a curvier, plus-size Cat, so we move further away from dominant representations.

[4.4] From my point of view, the writing was more about elements I wanted to include or change—fashions you might actually want to wear, rather than silly costumes, and more people of color—than things to avoid. I did explicitly aim to avoid coding Carnivale in the way Joker is often represented, in terms of gay deviance. I think he ultimately operates as a queer figure in the broader sense, but so do Cat, Enrique, Kit, Kay, and Dahlia, in that change, subversion, play, and fluidity are associated with positive values in this story, and it's monolithic, rigid straightness, in the form of Urbanite, that is really held up for critique and ridicule.

[4.5] Sarah Zaidan: I think the most effective way of answering this question is visually, with a rough draft of the cover art for MSCSI #1.

Figure 3. "Rough Draft, First Issue Cover," by Sarah Zaidan (http://ateliermitti.tumblr.com/post/28153296661/a-rough-draft-of-the-first-issue-cover-for-my). [View larger image.]

[4.6] Foremost in my mind was that this was not going to be a cheesecake image, and I wanted to get as far away as possible from presenting Cat as a sexualized object. So she might be getting dressed, but she's not showing off. Her expression may indicate an awareness that she knows the reader is looking at the cover—this work is meta in a lot of ways and I wanted to add an element to the cover that could be read that way—but she also knows the reader has come way too late to the party to engage in voyeurism, a subtle message that if you pick up this comic, you'll be getting a different representation of a female superhero. The placement of her hands holding her skirt shut as she finishes pulling up the zipper deliberately echoes the classic hands-on-hips superhero pose while subverting it: this is a superhero text, but with an everyday young woman as its protagonist. If she's got her hand on her hip, she's not doing it to pose; it's part of the everyday act of getting dressed. The papers and books surrounding her are a reference to her intellect and studies, and will include images and objects that subtly foreshadow her story in the final version.

[4.7] Suze Shore: Drawing the pages for the MSCSI comic has been very much about including a sense of reality in depicting both Cat and her environment. Since I'm working off Will's script, this isn't challenging; we're very much of one mind about giving the characters practical costumes and believable personalities.

[4.8] This approach is immediately avoiding the comic conventions I've never been keen on, namely the one-size-fits-all approach to female characters and the tendency to skimp on personality in favor of treating a character as a scene accessory. Will's script is circumventing these status quos wonderfully—Cat has depth that we're seeing fleshed out even within the first issue, and character images are being based off personality. That is to say, while there will be people sporting less than full coverage, it won't be at odds with those characters and their situations. Cat's larger figure later on in the story will take MSCSI another step further from the usual comic approach to female bodies and showcase a heavier girl being no less smart or capable than her previous self.

[4.9] Q: Sarah touched on getting "as far away as possible from presenting Cat as a sexualized object." Could you elaborate on specific elements of comics layout that might encourage or avoid such imagery? How does a storyboard for My So-Called Secret Identity work to challenge these stereotypes?

[4.10] Will Brooker: I played some conscious part in this process through specific directions in the script: the first page, for instance, notes that "the idea here is a sequence of 'girl getting dressed' that immediately subverts and offers an alternative to the more conventional cheesecake/tease scene."

[4.11] There are other moments where I've specified a deliberate angle or perspective that in some way subverts mainstream representations of women in comics—Cat sitting down in a library with a pile of books is described as "the hero shot," and there's a sequence where she explicitly closes the door on the viewer (and on Kat and Kit) when she gets changed.

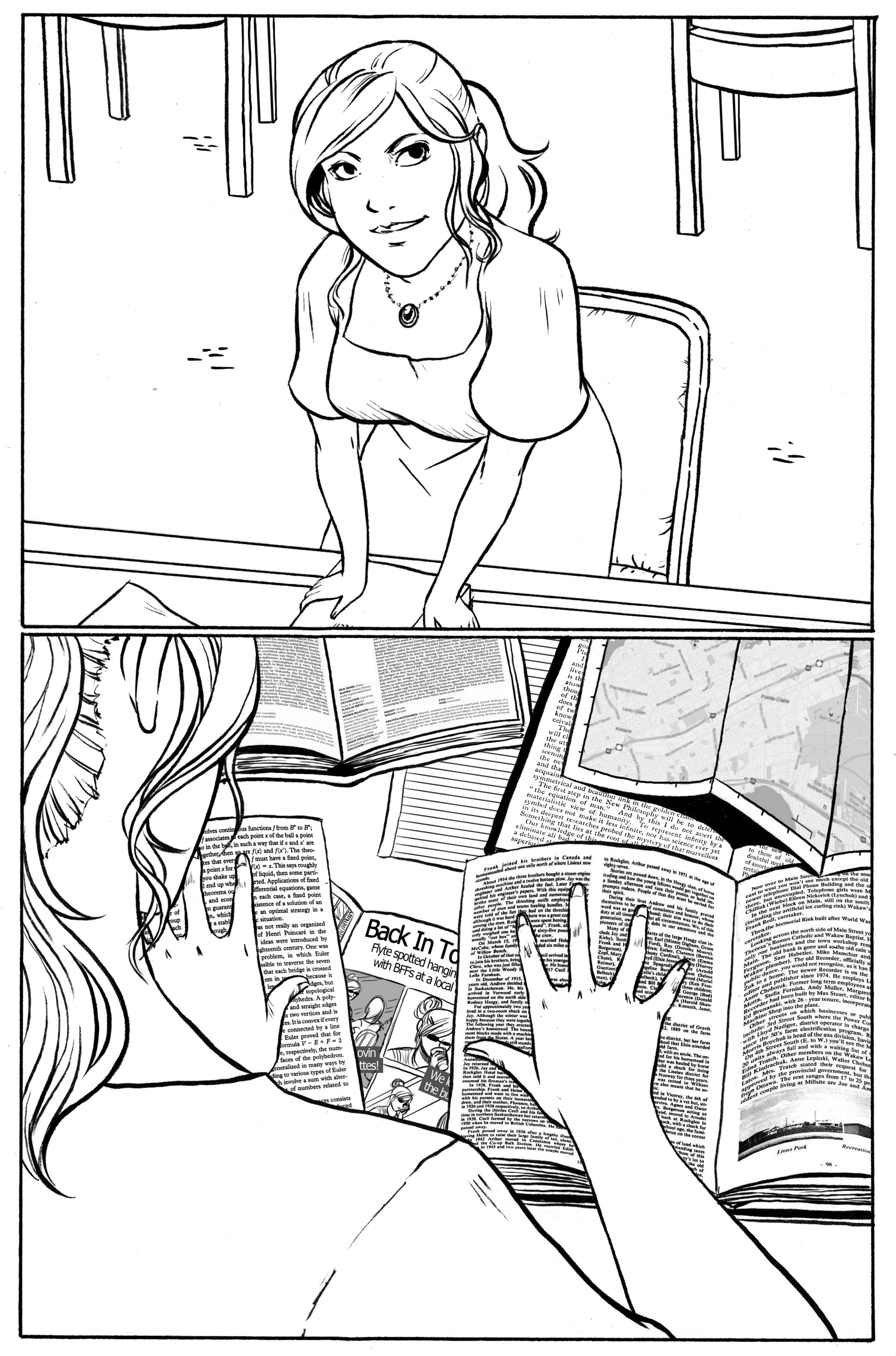

Figure 4. "Hero Shot," by Suze Shore. [View larger image.]

[4.12] In the second story arc, which I'm working on now, Kyla Flyte—a Supergirl/Britney Spears analogue—is practicing impossibly strained boob-and-butt Eschergirl poses (http://eschergirls.tumblr.com/) at one point. And the opening scene, set in a gym changing room, again explicitly tries to work against the mainstream sequences of Poison Ivy/Harley Quinn covered in suds and flicking towels at each other, or Catwoman and Batgirl in a nudist club, which I linked to in an earlier article, "Batgirl's Last Dance: The Brave and the Bold #33" (http://mindlessones.com/2011/06/08/batgirl-dance/).

[4.13] I think these directions could easily have been ignored or misinterpreted by artists who wanted to draw a different, more familiar type of comic, though, so really it's mostly been in the hands of Suze and Sarah, and the many artists who have drawn sketches and character designs for the project.

[4.14] That, thanks to Suze, the hero shot isn't just an image of a young woman with a pile of books in a library telling us she's really smart, but also looks down at her from above but without showing any cleavage, really epitomizes what this project is about and distinguishes it from (to pick a particularly relevant example) this cover image of Oracle.

Figure 5. Cover, Battle for the Cowl #2 (2009). [View larger image.]

[4.15] Suze Shore: The main concept I've been working with for issue #1 is to treat Cat's shots as is appropriate to what's going on in the story. I think a lot of comic artists flip this order of thinking; the first priority becomes "this woman must look sexy," and that sexual pose is then placed within the context of the scene whether it works or not. The best example of this would be fight scenes between women in which the poses have been taken from pornography. The result is a scene carried by the text and the accessories, with the basic posing and expressions of the characters entirely at odds with the situation.

[4.16] I've found that by using a scene's mood and context as my primary inspirations, it's been easy not to fall into the trap of nonsensical sexiness. My favorite sequence so far is the lead-up and reveal of Cat's hero pose in the library. To use this sequence—in which her superpower is revealed to be her intellect—as an excuse to break out sexually charged camera angles would have been utterly undermining.

[4.17] I wouldn't say I'm aiming so much to subvert stereotypes as I am to keep the characters real. When there is sexiness, it will be genuine to the character's personality.

[4.18] Sarah Zaidan: I adore the reveal of Cat's hero pose in the library; the energy she embodies in that scene is fantastic, and it came through in both the script and Suze's art. To me, what makes that image so powerful is that it's true to the character.

[4.19] What frustrates me about overtly sexualized imagery in comics is that it is very seldom in keeping with the personalities of the characters depicted; instead, it's just there. Perhaps a way to avoid this kind of imagery, or utilize it more mindfully, is to take a minute before drawing or writing to ask if it really needs to be there, taking into account the characters' personalities, motivations, and actions. For a femme fatale type like The Spirit's P'gell, overt sexiness has a point. For a character like Cat, it's out of place. Being on the same page about this as Will and Suze really adds to the experience of working on MSCSI.

5. Collaborative and transformative criticism

[5.1] Q: My So-Called Secret Identity is a collaborative project: although there is one author (Will), input was sought from a variety of readers and fans, and several artists contributed. Did you have any concerns about the feasibility of working by committee? What have the benefits and challenges been?

[5.2] Will Brooker: I think the collaborative approach is valuable for this project for a number of different reasons.

[5.3] Politically, I do think it's important to recognize privilege and try to make positive use of it. I have a decent reputation as a Batman scholar and have a variety of ways of gaining publicity for a Batman-related project (this roundtable discussion is one of them), so I think there is some value in me sharing that platform with a group of others and helping to showcase a range of creative talent. One key aspect I wanted to address was the traditional gender imbalance in mainstream comics, which I deliberately tried to reverse in terms of the people I initially approached.

[5.4] Aesthetically, the idea of a scrapbook was always key to the project. It connects to Barbara's scrapbooking—and while it's Jim Gordon who is sticking things in a memory album when Barbara is shot in The Killing Joke, I think scrapbooking, especially in its digital form of Pinterest, has associations of more feminine creative work, which distinguishes the project helpfully from mainstream superhero comics for teenage boys and young men. A scrapbook aesthetic also works to undermine any sense of a single, restrictive look for the characters—instead, we have various interpretations of Cat and the supporting cast—and gently subverts mainstream ideals of female representation in comics.

[5.5] Institutionally, comics are almost always collaborative, of course. So I would always have planned to work with visual artists, though I hope Sarah and Suze are getting a better deal of it than artists (and indeed writers) often have within the comic book industry.

[5.6] In terms of fan culture, I think (though again, it wasn't conscious) this way of working chimes with the practice of beta reading and collaborative online writing that's been long established within (predominantly female?) fan communities. So there may be something about transformative works that is particularly suited to joint creation.

[5.7] And on a personal, creative level, there were simply some things I didn't know well enough from personal experience. Enrique Garcia's character is hugely informed by lengthy online discussion with Juan Ramos, whom I first reached out to on Twitter. One of Cat's flashbacks about how she is treated within the academy was taken from a conversation with Sarah. L. J. Maher prompted me to think about the relatively uniform body types of all the women in the comic, and sparked the idea of a curvy Cat. The Egyptian stylings of Sekhmet are supported by research from another friend, Paul Harrison, who also provided ideas about Misper's fighting style; when Sekhmet's outfit started looking a little too showgirl, I ran it past feminist scholars—including the authors of this article—for their feedback. I've only just now had an e-mail from TWC editor Kristina Busse (about the idea of a mother yelling "Catherine Abigail Daniels!" at a freckled, tomboyish little girl) that made me realize we haven't seen the young Cat, and that it would be great to explore her childhood in a future issue.

[5.8] I feel the story is still in my voice, rather than written by committee, and overall I've been pleasantly surprised by the way conversations have always led to great new ideas, and haven't, so far at least, encountered any obstacles. Maybe it comes down to all being on the same page about what kind of project it is, and where it's going.

[5.9] Suze Shore: The committee-style setup of this project is one of the reasons I find MSCSI so rewarding to be involved with. We're doing something still relatively new with this series and, among other aspects, its treatment of sexuality and gender, and with such a range of voices within the comic, I believe it's essential to also have a diverseness in the voices guiding its production and direction.

[5.10] I think that the main challenges in this collaboration result from what is also its largest asset, namely the fact that we're from all over. Since geography requires we communicate via the Internet, there's always the risk that nuances of ideas get lost in transit. That being said, I've thus far been blown away by how in sync everyone has been and believe this similar vision combined with the contributors' individual uniqueness will result in a fantastically rich final product.

[5.11] Sarah Zaidan: This is the sort of project I've been waiting for ever since I went to art school and discovered I wasn't the only person out there who created characters and their worlds and visually realized them. What's surprised me about the process is the fantastic interplay of ideas that everyone involved has contributed, and how it really does create a visual and textual mosaic—all of which has served to create a stronger, better-rounded cast and setting. This makes the scrapbooking aspect of the project's imagery meta on another level, as it can be read as being representational of the process behind the project.

[5.12] Q: In some respects, My So-Called Secret Identity is part of a much longer fannish tradition of transformative textual production. This project has also come together in a year marked by vocal critique of the representation of women in comics, mounting concerns about the paucity of female comic creators, and projects like Womanthology, a Kickstarter-funded, fan-driven response to these concerns. Do you think there have been any signs that comics publishers like DC and Marvel are taking note of transformative works (and the criticisms/alternatives they embody)?

[5.13] Will Brooker: I'd love to say that they are, but I can't personally see any signs of it. As far as I know, Gail Simone remains the outstanding example of a female (feminist) fan entering the mainstream and shaping it from the inside, and unfortunately I get the sense she's being used by DC editorial as a kind of token fan service.

[5.14] I haven't personally met or spoken to Gail Simone, and I'm not an expert on her work. But I think it's wrong if one writer is expected to shoulder the responsibility of female representation within DC Comics. It's wrong for a range of obvious reasons, including the fact that one person can't adequately live up to that expectation and is limited in what she can do within the dominant system. I like Simone's work on Birds of Prey very much, but her recent run on the New 52 Batgirl has disappointed me. It reads like what I expect it is—a compromise and negotiation.

[5.15] So it's great to see the transformative works on offer this last year, and the boundaries between fan and professional seem to be blurring further with Kickstarter-funded projects, but I think the DC mainstream has a long way to go.

[5.16] Sarah Zaidan: Researching for my PhD, it became clear to me that while male superheroes are representations of each era's desirable characteristics for masculine figures, female superheroes, more often than not, represent projections of male desire instead (although how this is defined does vary from era to era).

[5.17] As more years pile up between the 1990s and the era of "bad girl" comics, I keep hoping that mainstream publishing leaves behind their legacy, but then things like Starfire and Catwoman in the New 52 happen and my optimism erodes. What's heartening, though, are the emergence of things like the plethora of negative responses the New 52's depictions of Catwoman and Starfire garnered, and projects like this one and Womanthology. To me, this indicates that not everyone reading comics is content to consume what's on offer. Nevertheless, there definitely is, to echo Will, a long way for mainstream publishers to go.

6. Note

1. Will Brooker: "Team Cat" is a flexible group of several artists, critics, scholars and commentators, some of whom contributed feedback and advice on the script, while others added costume design, cover art, or character sketches. Suze and Sarah have been most consistently involved since the project inception, though Jen Vaiano was the first to draw Cat and her supporting cast, and Clay Rodery has recently expanded the art portfolio with his own take on the characters. Others offered early input and have not been involved with the project's later stages, but they still deserve credit and thanks. The roster of current and former contributors is as follows. I've listed all the women together because I think it helps make the point about attempting to reverse industry norms (a male-female ratio of 4:15 at the moment).

- Karin Idering (http://www.karinidering.com/)

- Suze Shore (http://www.smuze.net/)

- Jennifer Vaiano (http://noflutter.deviantart.com/)

- Sarah Zaidan (http://ateliermitti.tumblr.com/)

- Sisley White (http://sewwhite.com/)

- Hanie Mohd (http://haniemohd.blogspot.com)

- Lea Hernandez (http://divalea.livejournal.com/)

- Susana Rodrigues (http://comicsfashiondivas.tumblr.com/)

- Paige Halsey Warren (http://paigehalseywarren.carbonmade.com/)

- Sandra Salsbury (http://www.sandrasalsbury.com/)

- Karen Healey

- Carlen Lavigne (Twitter @clavigne)

- Kate Roddy

- L. J. Maher

- Suzanne Scott (http://www.suzanne-scott.com/)

- Clay Rodery (http://www.clayrodery.com/)

- Paul Harrison

- Juan Ramos

- Will Brooker