1. Introduction

[1.1] In this article I explore how the Ross Bakery Inn and Ross Village Bakery in Australia's southernmost state of Tasmania has become the destination for a steady stream of Japanese tourists who are fans of the popular Japanese anime Kiki's Delivery Service. The analysis of these tourist-fans' playful and critical activities contributes to research within fan studies which has explored the role of place and travel (see Hills 2002; Couldry 2000, 2007; Jenkins 2004) as well as broader research around the types of skills and literacies emerging within fan and youth media practices (Jenkins et al. 2006; Knobel and Lankshear 2007; Livingstone 2011; Black 2009; Lyman et al. 2009; Gee 2007). Through investigating the ways in which fans articulate their experiences, identities, and motivations while visiting the Ross Bakery I will suggest that, in addition to understanding the media's role in contributing to our perception of place, we must also address the cultural and emotional contexts which underpin the appeal of these media pilgrimages. Through analyzing visitors' comments in the Ross Bakery's guest books I will reveal the cultural and emotional issues facing the Ross Bakery's status as a Kiki media pilgrimage destination. Through this case study I will explore both the opportunities for fresh perspectives of a location and the risks these places face if they fail to measure up to an idealized fictional image. It is within the disjunctures and continuities between the fans' virtual and real maps that this article will explore how fans use Kiki as a scaffold to interpret their travel experiences.

[1.2] My use of the term scaffold follows that of Black (2009), Hoge (2011), Lewis (2004), and Thomas (2007) and should be understood as referring to a transformative or reworking process whereby fans draw upon the original textual world as a scaffolding to help structure, organize, and foster an audience for their own narratives, experiences, or ideas. While scaffolding is most often used to describe the process of fan fiction writing, I see a similar process occurring in the reflective travel stories written by Kiki fans in the guest books of the Ross Bakery. It is through this extratextual focus on how fans use physical places and locations related to Kiki as the building blocks for their own work and the role of visitor comments in guest books as pseudo fan fiction that this article makes an original contribution to our understanding of the creative processes whereby the real and fictional are transformed and reworked.

2. Approach—Locating a media pilgrimage

[2.1] As Connell's (2012) recent overview of film tourism reveals, there are various ways to explore how and why fictional worlds become grafted onto real-world locations. Within the impact of film tourism on a location, these include concerns around film and heritage (Higson 2006; Sargent 1998), authenticity (Butler 2011), and appropriation (Jones and Smith 2005; Light 2009). Related concerns include the marketing of these film locations (Busby and Klug 2001); and the motivations, experiences, and perception of tourists (Im and Chon 2008; Peters et al. 2011). It is the latter that is the focus of this article—particularly the motivations, experiences, and perceptions of tourists as fans.

[2.2] Couldry's (2000, 2004) research on audiences who traveled to the set of the British TV show Coronation Street has been particularly significant in further unpacking the experiences of fans who embark on media pilgrimages to film locations. Couldry defines media pilgrimages as not only involving the physical act of traveling to a film location, but also the symbolic act of temporarily crossing the boundary from one's ordinary everyday life into the special world of media. However, Couldry argues that this play between worlds never threatens the integrity of the boundary between these worlds. Rather, these media pilgrimages reinforce the separation of these two worlds and validate the specialness and magic of the media world.

[2.3] Reijnders (2010) draws upon Couldry's (2000, 2004) argument that media pilgrimages involve a symbolic journey from the ordinary to the special in his research on James Bond fans traveling to film locations. While Reijnders agrees with Couldry's distinction between physical and symbolic journeys, he broadens his analysis beyond the normalization of media power to include the cultural embeddedness of other power structures such as gender and ethnicity that also frame these media pilgrimages. In the case of James Bond film tourism, Reijnders (2010, 370) argues that to understand the motivations, experiences, and perceptions of Bond fans, we need to understand how their media pilgrimages "reconstruct…dominant gender discourses" in addition to the questions around media power that Couldry raises.

[2.4] While I agree with Couldry's (2000, 2004) analysis of media pilgrimages as a way to highlight the relationship that fans develop between the ordinary and media worlds, drawing upon Reijnders's (2010) work we can see that there are additional relationships beyond the fan and the media being negotiated. Rather than centered around the power of media institutions and the challenges people have in interrogating the power of media to frame our view of the world, I instead aim to explore the ways in which notions of being a fan relate to other symbolic frameworks, particularly social conventions around personal transformation such as coming-of-age and maturity.

[2.5] Matt Hills (2002) also contributes to this broader question of the emotional and textual practices of fans by arguing that they create cult geographies where places are redefined around pop culture associations. Hills explains that a cult geography is a place where we can see how fans inhabit a specific place through various practices such as reenacting a scene or other performance that reorders that location's meaning around their relationship with their favorite text. Through his analysis of fans of The X-Files traveling to Vancouver to visit filming locations, Hills observes that "the 'inhabitation' of extratextual spaces forms an important part of cult fans' extensions and expressions of the fan-text relationship" (2002, 144). In addressing how fans inhabit these extratextual spaces, my aim in this article is to similarly explore what it means to be an anime tourist at the Ross Bakery and the ways in which fans synthesize information and experiences to arrive at a playful or critical view of the experience.

[2.6] My main interest, then, is to explore how fans frame their media pilgrimage to the Ross Bakery and how this frame is questioned and interrogated within the fan community. Approaching media pilgrimages in this way broadens our understanding of the motivations, experiences, and perceptions of tourists as fans. This approach addresses the media pilgrimage experience as having contradictions and conflicts as well as acknowledging the reinforcement of existing hierarchies of power, such as that held by media institutions (Couldry 2000; Couldry and McCarthy 2004). As Reijnders argues, "the authority of the media does not come about in a vacuum, but is tightly interwoven with other power configurations" (2010, 376). To fully appreciate media pilgrimages, they must be understood in their wider cultural context.

3. Transformative processes

[3.1] I examine the use of two key processes involved in fans remixing the fictional into the real: the media pilgrimage (Couldry 2000) process, where fans bridge the ordinary reality around them with the fictional ideal of a media text, and the media scaffold process, where fans use the Kiki story as a framework to develop their own account of traveling to Ross to reflect on their life and experiences. In exploring how Japanese tourists connect Kiki to Ross, I will build upon both a media pilgrimage focus and work in the field of media literacy that has explored the ways in which fans and consumer groups participate in and transform media content (see Jenkins 2004; Thomas 2007; Black 2009; Hoge 2011).

[3.2] The process of fans using existing places as building blocks for fan fiction work or fan performances (such as restaging memorable scenes to photograph) has been related to the development of media literacies and practices (Hills 2002). The skills and practices emerging from affinity-based communities such as fans has also been an important area of investigation within media literacies and issues of online participation (Jenkins et al. 2006; Knobel and Lankshear 2007; Lyman et al. 2009; Gee 2007). Research around media literacies has begun addressing the types of pedagogical value that play has in assisting young media users to develop new skills and tap into a supportive peer network. Recent research has explored the types of affiliations, creative work, collaborative problem solving, and circulation of content that is occurring in fan communities (Jenkins et al. 2006; Knobel and Lankshear 2007; Lyman et al. 2009). Of particular relevance to this article is recent work that has examined the social and discursive literacy practices of young people who write fan fic (Hoge 2011; Lewis, Black, and Tomlinson 2009; Black 2009; Thomas 2007). This research has examined how fans draw upon the characters, settings, and stories of their favorite pop culture worlds and use these as a scaffold or entry point for their own writing. Here I refer specifically to Thomas (2007), who draws upon the work of Jenkins (2004) and Lewis (2004) to describe fans using popular culture as a scaffold or launching point for writing from which they develop something new.

[3.3] In Lewis's analysis of children's fan fic writing, she argues that "what fan fiction offers to these young writers is a great, existing story line; interesting, three-dimensional characters that have already been developed; and a wealth of back story to both pull from and write about" (2004). The fans described by Lewis are able to confidently develop and craft a story of their own and not be overcome by the stress of imagining an entirely new world with believable characters, settings, and histories. Similar arguments have been made by Thomas (2007), Black (2009), and Jenkins (2004), who supports the idea that "not everything that kids learn from popular culture is bad for them: some of the best writing instruction takes place outside the classroom" (Jenkins 2004). In terms of this article, like the focus on the active designing and transforming of original content by fan fic writers, the Kiki fans visiting the Ross Bakery similarly build upon a fictional world to develop something original around their journey to Australia. Like the use of the term scaffold to describe the emerging literacy practices of young writers occurring in fan fic (Lewis, Black, and Tomlinson 2009; Black 2009; Thomas 2007; Jenkins 2004), my use of the term attempts to draw attention to the value of popular culture for these tourist-fans to negotiate a complex and challenging journey, often for the first time.

[3.4] In analyzing the ways that fans appropriate the Ross Bakery into the Kiki story, it soon becomes apparent that the story, location, and characters of Kiki provide a rich but contested scaffold for the travelogue of the Japanese tourist, working holiday visa holder, and international students. My primary interest, then, is how the posts and comments in the guest books use Kiki as a scaffold and entry point from which to develop an understanding of their experiences and identity.

4. Methods

[4.1] The analysis presented in this article is based on three methods: a discourse analysis of three guest books, which totaled 302 pages and included over 600 individual comments; an in-depth interview with the Ross Bakery owners; and participatory observations during my field study at the Ross Bakery. While limited information was available on the sociocultural background of the tourist-fans, the guest books provided rich and varied data in terms of the ways fans describe their immediate experience of staying at the Ross Bakery. These guest books were kept at the Ross Bakery's Kiki's Room accommodation. This room was set aside for Kiki fans because of its resemblance to the room depicted in the anime. As Dot, the owner of the Ross Bakery, put it during our interview: "Because a lot of Japanese wanted to stay around and wanted to take photographs, we had a little attic in the back, and the only reason we called it Kiki's Room, was because it was a little attic, and [in the anime] Kiki was in an attic."

[4.2] The guest books span the years from 2004 to 2007 and include comments written in English and Japanese as well as drawings and sketches made by visitors. This article draws upon key comments in these guest books to show the fans' experience at the Ross Bakery. In order to preserve the tone and expression of these guest book entries I have not corrected their grammar or spelling. I feel this is important as it reveals some of the challenges in explaining the spread of this rumor by Japanese to non-Japanese speakers. However, where the comments were written in Japanese, I have had these translated into English as indicated.

[4.3] In addition to these close readings of the guest books, my observation of the Ross Bakery involved visiting Ross and interviewing the owners, Dot and Chris. This 1-hour, semistructured interview explored the origin, history, circulation, and production of the Ross Bakery's link to the Kiki story from the owners' perspective. This interview was transcribed and included within my overall project data.

[4.4] My own participatory observations complemented the data collected in the guest book comments and interview data. My observations during my stay at the Ross Bakery focused on two aspects of the phenomenon: general tourism practices around heritage, national identity, and cultural objects; and fan practices (issues of authenticity, privileging particular objects/actions, circulating the story, and fan art/performances). These observations were recorded in a notebook during the field research (Silverman 2001; Bryman 2004).

[4.5] The guest books, transcripts, and notebooks were compared for key similarities that would indicate broad, shared structures of this phenomenon. Special focus was applied to descriptions of visiting the Ross Bakery and any differences or conflicts within these experiences that brought the site under scrutiny. Comparisons between individual tourist comments were analyzed as well as broader differences around the environment and culture of the Ross Bakery and the township of Ross. As I will show, these comments reveal a spectrum of efforts to negotiate the surroundings through the lens of Kiki. This analysis uses an approach common to ethnographic studies within fan cultures of interviews, observations, and close readings of fan comments and creative expressions (see Jenkins 1992; Bacon-Smith 1999; Baym and Burnett 2009; Bury 2005; Whiteman 2009). To contextualize the continuities and discontinuities between Kiki and the Ross Bakery and the playful or skeptical reactions it prompted, some background will be provided on each below.

5. Kiki's Delivery Service

[5.1] Kiki's Delivery Service is a feature-length animated movie from Japan released in 1989 and directed by the well-known anime director Hayao Miyazaki. An English-language version was released in the United States in 1998, the United Kingdom in 2003, and Australia in 2004. Known in Japan as Majo no Takkyūbin (literally The Witch's Delivery Service), it was based on a popular novel of the same name by Eiko Kadono published in 1985. In Japan it was the highest-grossing film on its theatrical release in 1989 and the best-selling anime DVD for June 2001. The story focuses on a rite-of-passage journey of Kiki, a 13-year-old witch, who must complete her training by moving to a distant village for a year. She and her black cat, Jiji, fly to a seaside village and are taken in by the kind owners of the local bakery. It is here that Kiki learns to overcome a number of obstacles by establishing a flying delivery service for the area.

[5.2] As I will show, the film's focus on the personal dilemmas of Kiki and the sanctuary she finds at the bakery provides a clear link to the comments left in the guest books, with many messages deliberately drawing upon similar motifs of travel, comfort, and personal transformation such as coming of age or gaining further maturity.

6. The Ross Bakery Inn and Ross Village Bakery

[6.1] Tasmania's historic town of Ross is regarded as one of Australia's most beautiful convict-built stone villages. Bypassed by Tasmania's Midland Highway (the main route between Tasmania's two biggest cities, Hobart and Launceston), Ross is secluded from much traffic and casual interest. An online article in the Australian newspaper The Age provides a typical preserved heritage frame to promote the appeals of visiting Ross, stating that its seclusion has helped to preserve its pristine heritage status and prevent it from being "corrupted by modern tourism" ("Ross" 2004). As a location heavily dependent on tourism to generate revenue, Ross relies on its heritage features and atmosphere to draw visitors in.

[6.2] Ross's attractive village layout gives rise to powerful historical and colonial associations; for example, the main crossroad of the village is said to represent Temptation (Man O'Ross Hotel), Recreation (Town Hall), Salvation (the church), and Damnation (the gaol). And it is within Ross's colonial-era buildings and charming village layout that the Ross Bakery has developed a connection to Kiki's idealized vision of a small, early-20th-century European town. However, as I will show, the Ross Bakery's connection to Kiki extends beyond surface similarities. To produce such a resilient, global popular culture connection, there have emerged a number of deep thematic links between Kiki's narrative and the personal journey of those visiting the Ross Bakery.

7. The Kiki fan identity

[7.1] In the guest books, fans presented their identity and what it meant to travel to the Ross Bakery in two different ways: first, by celebrating the similarity between Kiki and the Ross Bakery by adopting the identity of the main character, Kiki, and improvising links between the anime and the atmosphere and services of the Ross Bakery, and second, by adopting a more skeptical stance toward the link by questioning the credibility and reliability of the rumor and raising concerns about the motivations, unconnected to fannish concerns, of the Ross Bakery's owners.

[7.2] Some of the strongest expressions of being a fan on a media pilgrimage were configured around a transformative journey. In particular, fans drew a connection between their experiences in Australia and Kiki's efforts to mature into a witch and be accepted in her new town. Consider for example, the following comment:

[7.3] I think my working holiday life is like Kiki's life, because Kiki was looking for a place to live and work, and she was learning many things in a foreign place. Although I was fired from my job, my girlfriend broke up with me, and I've become homesick, I am so happy to stay at the bakery today. I want to say to my parents thank you very much for letting me go to Australia. (Translated from Japanese into English)

[7.4] In this case, by identifying with Kiki's coming-of-age story, this fan establishes a deep, personal link between life experiences, the Ross Bakery, and Kiki. The fan here draws upon key motifs from the anime such as facing a series of challenges in a foreign land, finding comfort and sanctuary in a local bakery, and the need for critical self-reflection to resolve past insecurities.

[7.5] A similar media pilgrimage as transformation can be seen in the opening words for this fan's guest book entry: "I traveling in Australia about one month by myself. The title is look for Ghibli world and look for myself." The entry concludes with, "I'm happy I can stay kiki's house. It was my dream. I'm looking forward tomorrow breakfast. Thank you."

[7.6] Titling the entry "look for Ghibli world and look for myself" emphasizes that the fan is on a journey of change and self-discovery, a type of transformative journey that many fans explicitly embarked upon on their journey to the Ross Bakery.

[7.7] This transformative narrative can also be seen in different ways, such as in this comment: "Cried when watching video even though Im 23 (Valentines day)." The emphasis on Valentine's Day suggests the romantic first love subplot in Kiki where she develops growing affections toward a local boy.

[7.8] The emphasis of childhood or youthful memories reveals a foregrounding of particular coming-of-age moments within the transformation motif—leaving home for the first time, traveling overseas, working and studying in a foreign country, and feeling the emotions of blossoming love. These are all central to the narrative of Kiki and reinforce a link between the themes of Kiki and the fans' journeys to the Ross Bakery. Both Kiki and the Kiki fan leave home to travel to a distant foreign town and experience personal growth and change. As the above comments show, these links are explicit for some fans—"I think my working holiday life is like the Kiki's life"— and provide a highly personal link between their time at the Ross Bakery and Kiki. It is through this type of connection that the emotional authenticity of the Ross Bakery as a type of cult media pilgrimage becomes established.

[7.9] Like the point of entry into mature writing that Jenkins (2004) described Harry Potter fan fic writers experiencing as their writing and networking skills grew in sophistication, these personal transformation stories involve a similar reworking of a familiar media text as a starting point to express a deeper personal story.

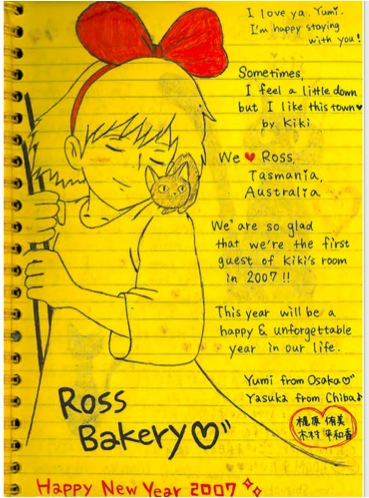

[7.10] The fans' identification with Kiki and her coming-of-age narrative suggests that media pilgrimages involve a meaningful remixing of the fictional into the real to produce creative expressions, such as the sketches in the guest books (figure 1), and stories of discovery, such as the deeper reflection on their past and current aspirations. For the Kiki fan, visiting the Ross Bakery provides a starting point for a deeper reflection and negotiation of the challenges faced while traveling across Australia. Through Kiki, the fans gained a fresh perspective on the challenges and adversities they faced. Much like the young fan fic writers who develop a stronger writing voice through using their knowledge of existing media franchises and characters, such as Star Trek or Harry Potter, as a scaffold around which to develop their own stories (Lewis, Black, and Tomlinson 2009; Black 2009; Thomas 2007; Jenkins 2004), so too these tourists draw upon the Kiki world to provide a shared worldview with which their fellow travelers can identify and through which they can economically express their experience of cultural, geographical, and identity changes. In this case, the appropriation of popular culture involves a starting point to begin a deeper reflection on the fan's own coming-of-age or self-discovery story while traveling and living in Australia.

Figure 1. Ross Bakery guest book sketch (Yumi and Yasuka 2007). [View larger image.]

7. Kiki and nostalgia

[7.1] The appearance of the coming-of-age or self-discovery frame within these guest books is not surprising given that most of the Kiki fans who visit the Ross Bakery are young. While no accurate data were available to provide an accurate average age or gender for the Kiki fans, in my interview with the Ross Bakery owners, they estimated the age of most of the Kiki fans as "around about late teens, twenties. They are the main. But what we are finding also is that Japanese families are coming now, so older parents with their children."

[7.2] While the majority of fans were described as young, it is interesting to note that even for those older fans who visited the Ross Bakery, the coming-of-age frame is still evoked. As the following comment shows, it can be based around the nostalgia of the past and memories of childhood:

[7.3] First time I saw Ross Bakery and Kiki's room. I thought really looks like "Majyo no Takkubin" movie's situation. When I was child I often watched this movie. So I'm really happy I watched "Majyo no Takkyubin" today in Kiki's room. I never forget that watched movie in Kiki's room and ate bread & pie in Ross Bakery and stayed in Kiki's room. I could experienced at movie world!! Next if I'll be visit to Australia again, I'll certain to come here again. When I'll go back to Japan, I'll recommend to stay here for my friends. Thank you very much for great & dream time for me.

[7.4] The remembrance of childhood is a related theme repeated throughout the guest books, with comments such as "We had a nice time to stay here and remember our childhood in Japan." Expanding upon the transitional coming-of-age frame, here the media pilgrimage is presented around fond memories of childhood and youth. For these fans, the opportunity to express nostalgic sentiments of childhood through inhabiting Kiki's location is an important process of the media pilgrimage. Similar to Roskill's (1997, 202) "landscapes of presence" or Morgan-James's (2006, 199) notion of "emotional territory," experiencing a film landscape enables the tourist to refer to broader, difficult-to-express concepts or notions such as nationhood, identity, or cultural zeitgeist. Here, the encounter with the film landscape allows one to "express what is otherwise inexpressible" (Lefebvre 2006, xii).

8. The Ross Bakery as cult geography

[8.1] The framing of the Ross Bakery through a transformative narrative is similar to the creation of a cult geography by fans described by Hills (2002), which involves fans reinterpreting the meaning of a place around their fan interests. For Hills, visiting a cult geography involves fans reordering the meaning of a location through experimenting, improvising, and discovering links between their surroundings and their favorite text. Fans can take on the identity, characteristics, and practices of fictional characters within these environments, as Hills explored in the case of fans of The X-Files self-consciously adopting the investigative motifs from this TV series while tracking down shooting locations.

[8.2] The Ross Bakery's cult geography status is particularly apparent when fans describe the reason why their itinerary to Australia includes the remote location of Ross, Tasmania. As seen in the earlier post where the fan writes "find Ghibli and find myself," while the Ross Bakery has none of the glamour or cachet of other tourist designations such as Ayers Rock or the Great Ocean Road, it equals and may surpass these locations because of its connection to Kiki. This is further emphasized through the decision to leave the Ross Bakery to the last and reflect upon the entire trip through the experience in that place. Even the Ross Bakery's owners were familiar with the different ranking of tourist destinations that underpinned the Kiki fan's decision to travel there.

[8.3] Chris: We had a couple here that came to stay with us a few years ago, and they were on a 3-week tour of Australia—they were Japanese, and they tell us, they had to make a decision, they were on the Gold Coast, and they had to decide do they go to Ayers Rock or Ross Bakery. So they knocked off Ayers Rock—

Interviewer: But so many people would express incredulity at why would Ross beat Ayers Rock.

Chris: Well, I would suppose it had something to do with the fact that it was going to take them 10 days to get to Ayers Rock; it would have been easier to come down here. But I think it's sort of—it becomes a sort of rite of passage, a pilgrimage.

[8.4] While these distinctions between ordinary tourist destinations and special media pilgrimage locations highlighted the agency of fans and their reordering of top locations to visit, the value of the Ross Bakery as a Kiki location did not exclusively center on Kiki's narrative.

9. Local food and atmosphere

[9.1] While the self-discovery or personal transformation narrative was a dominant expression of what made the journey to the Ross Bakery memorable and satisfying, there were other motivations and experiences that moved beyond the privileging of the Kiki text. Within the guest books, this was revealed through descriptions focused on enjoying the local food and atmosphere of Ross and its bakery. These experiences not only reveal the agency of fans to express their own interests and expectations beyond Kiki, but also emphasize the broader tourist practices of sampling local produce and soaking in the atmosphere of a foreign location that can occur in parallel to media pilgrimage practices.

[9.2] In discussing their broader experiences of the Ross Bakery, fans repeatedly mentioned their enjoyment of the Ross Bakery's food, especially its pies. This was expressed in different ways, but typically it reinforced a positive link between the Ross Bakery and Kiki. For example,

[9.3] Finally my dram has come true ! ! Ive been waiting for the day when I can visit Kiki's room. Ive had a lovely pie at the bakery. That was the best pie which I ever had in my life.

[9.4] And,

[9.5] The primary reason I visited the bakery for the first time was to see the bakery itself as a fan of Miyazaki's movies. From then on, I visited there several times because I loved the village of Ross and its environment, and delicious pies sold at Ross Bakery.

[9.6] While this fan may have been motivated to visit Ross because of Kiki, the discovery of delicious food and a comfortable atmosphere were important additions that deepened the enjoyment of the trip.

[9.7] Other more pragmatic associations grew out of a media pilgrimage, including Ross's convenient location as a stopover on the long drive between Hobart and Launceston:

[9.8] At the first time I was interested in Bakery as a model of Kiki's Delivery Service, but after that it became less important. Now, for me, Ross is a good rest point with a good bakery on the way to Launceston.

[9.9] Even those fans who were less convinced that the Ross Bakery provided the basis for Kiki's bakery were still impressed by the atmosphere of the town and how this evoked the spirit of Kiki:

[9.10] The bakery itself is slightly different from the bakery in Kiki's Delivery Service but I think the atmosphere of the town suits the image of the movie. (Translated from Japanese into English)

[9.11] Or they found it to be a pleasant location to visit by itself:

[9.12] While the bakery didn't look similar to Kiki's bakery on the outside, its (and the town's) atmosphere was very good and the oven-baked bread was so nice. (Translated from Japanese into English)

[9.13] By emphasizing the atmosphere of Ross and the Ross Bakery, these fans establish a positive experience of the trip while still maintaining a skeptical position toward the rumor linking the Ross Bakery to Kiki. While the concern around the Ross Bakery's authenticity is primarily based on visual and structural differences, the emphasis on the pleasures of eating pies and enjoying the atmosphere of Ross suggests an important emotional experience that underpins a positive media pilgrimage. This suggests that structural similarities between Kiki and Ross are only one element of authenticating Ross Bakery as a Kiki media pilgrimage location. The power of emotion and mood to underpin the discovery of the idealized Kiki bakery further reinforces Roskill's earlier point that media pilgrimages can be more about evoking impressions and emotions through the "landscapes of presence" (1997, 202) or Morgan-James's (2006, 199) "emotional territory" than simply being a one-to-one visible match.

[9.14] While some fans discovered a broader emotional link between Kiki and the Ross Bakery, nevertheless, as I will show in the final section, there were fans who directly challenged the link and argued that the Ross Bakery should not claim a connection to Kiki.

10. The dislocation of a media pilgrimage

[10.1] So far I have explored the positive ways in which fans framed their experience of Ross and the Ross Bakery through playful discovery and improvisation. In this final section I will discuss how fans raised questions of authenticity and credibility. These criticisms are important because they reveal attempts by fans to protect the integrity or value of Kiki from what they see as incongruous appropriations.

[10.2] While most of the comments in the guest books were positive and reinforced the links between the anime and the Ross Bakery, there was criticism of the experience. In contrast to the types of identifications and discoveries that characterized the fans who saw their trip as a transformative moment, those challenging the link raised three areas of concern: structural differences between the two, doubts around Ross's atmosphere being an entry point into the Kiki world, and anxiety around the intentions of the Ross Bakery owners.

[10.3] Consider, for example, the following complaint that the atmosphere of the Ross Bakery and its rustic nature was very different from the idealized vision of a bakery in Kiki:

[10.4] This room isn't similar to Kiki's room in the film at all. They should keep this room clean when they offer this room to guest though here is an attic. I couldn't sleep well because bakers began to work pretty early. It was damn noisy.

[10.5] This challenge to the Ross Bakery's appropriateness as a Kiki pilgrimage site is framed around the all-too-real atmosphere of sleeping above a bakery with its accompanying noise and mess.

[10.6] Other posts similarly felt the atmosphere and actual physical experience of visiting the Ross Bakery did not match their expectations of Kiki's bakery.

[10.7] I don't want to come back to Ross. I think Kiki's room is different from my image of the movie. I don't like the place because there are many insects there. (Translated from Japanese into English)

[10.8] This rejection of the Ross Bakery draws upon both the structural differences between the two and also the unpleasantness of being confronted with the ever-present nuisance of insects in Australia. Unlike the earlier positive experiences of Ross's atmosphere where Kiki acted as an entry point into discovering pleasant tourist experiences around country life, this post instead reasserts how far away the fantasy image of Kiki's village and bakery can be from the experience of staying at a bakery in a small regional town.

[10.9] As Mordue argues, when visiting a film location, the dissonance between a real location and its portrayal in film or TV results in "often messy and contradictory interactions of people and place in a tourism context" (2001, 32). In a similar way, rejecting or embracing Ross's regional atmosphere by Kiki fans is related to the struggle of comparing the idealized Kiki bakery to the real Ross Bakery. Add to this other tourist demands—particularly expectations around receiving appropriate services and comforts—and it becomes clear how difficult it is for a media pilgrimage to satisfy everyone's needs.

[10.10] In addition to these disappointments, the commerce of tourism was also seen to threaten the fans' expectations around the appropriate ways to benefit from the Kiki connection. In these instances, anxieties around the media pilgrimage status of the Ross Bakery are often framed as moral concerns. This is particularly the case for those who felt that the Ross Bakery owners were exploiting the Kiki association for financial gain. Some were ambivalent at the supposed need for the Ross Bakery's owners to generate a profit, such as:

[10.11] Such a good business! I really liked Kiki's room, but I think the price is a bit expensive. However, the owner is a businessman at heart, because he promotes the room as Kiki's room. (Translated from Japanese into English)

[10.12] Other fans saw themselves as defending the value and integrity of the anime's vision. In this case a number of comments expressed concerns about how the original copyright holders, such as the creator Miyazaki, may not be happy with the Ross Bakery's claims.

[10.13] This is very rude to Miyazaki!! While the inside of the building looks like the image of the movie, the outside looks absolutely different. I think this rumor is very rude to Miyazaki. Who started talking about this rumor? (Translated from Japanese into English)

[10.14] Fan concern here is around the appropriateness of the Ross Bakery's status as a Kiki location and broader concerns around the cultural ownership of Kiki. Here we find examples of the type of damaging commercial practices that Hills (2002) identified as undermining the authenticity and legitimacy of media locations in the eyes of many fans. Hills argues that locations become enduring cult geographies because fans directly participate in the discovery and framing of the links between locations and their favorite media texts rather than local businesses proclaiming a link. Hills suggests that through this participation, fans themselves authenticate a media location.

[10.15] While the Ross Bakery owners described their efforts to meet fan expectations—such as allowing visitors to wear staff aprons for photographs, conducting tours of the kitchen to see the wood-fired oven, and going to the attic to see Kiki's room—the demands of running a café and bed-and-breakfast venue inevitably meant that they couldn't meet every request. Regardless of the daily operating demands that make this gatekeeping necessary, the consequence is that some fans feel that their pilgrimage activities are restricted. This frustration can be seen in the following guest book comment:

[10.16] Even though it takes advantage of the rumor to attract tourists, it does not allow visitors to take a look at its inside. When I went there I also was not happy with the manner of its shop assistants, which was rather disappointing. (Translated from Japanese into English)

[10.17] Comments like this display a morally invested, protective fan identity that defines itself against the motives or agendas of nonfans. This is an identity built around a strong sense of investment and possessiveness over Kiki.

[10.18] An interesting aspect of these judgments is that they emphasize either physical differences, an atmosphere that takes one out of the Kiki world, or moral concerns around commercial exploitation. This spectrum of concerns ranging from the concrete to abstract shares a similar structure to those who embraced the Ross Bakery, which ranged from discovering physical similarities to more intangible emotional resonances. This debate around the appropriateness or authenticity of the Ross Bakery as a Kiki location reminds us that there are deeply conflicting notions of what makes a satisfying media pilgrimage.

11. Conclusion

[11.1] The analysis presented in this article has focused on the forms of improvisation and discovery adopted by Kiki fans as they negotiate the similarities and differences between the Ross Bakery and the anime Kiki. Drawing upon the comments in the guest books and interviews with the Ross Bakery's owners, I have examined the ways in which this community synthesizes information around the Ross Bakery and Kiki. I have also explored what key practices are occurring in media pilgrimages today, particularly the ability of fans to adopt alternative identities, reimagine their surroundings, and evaluate the credibility of these locations.

[11.2] As I have shown, while there are some dominant experiences shared by fans who visit the Ross Bakery, there was also conflict around the value and legitimacy of the experience. These moves involve arguments around playful or skeptical discourses that seek to legitimize experiences of the Ross Bakery. In this context, the experience of the Ross Bakery via Kiki is an example of the contested ways in which a location becomes co-opted into a media pilgrimage by a diverse community.

[11.3] In a similar way that Hoge (2011, ¶6.2) notes how the fan fic writers use "the scaffolding of the textual world…as an act of play, and an actively ludic opportunity for engagement," so too the agency of fans to impose their own Kiki-influenced narrative or to adopt the identity of Kiki to improvise and explore a world they would like to inhabit, onto the Ross Bakery is a form of play that integrates an existing fictional text with the fans' experiences and imagination. As Jenkins (2004) has argued, fans should be seen as active engagers and users of media content. However, in talking about media pilgrimages as scaffolds, my concern has not been to assume that all fan engagements with locations will lead to a positive, fulfilling experience or bring any real understanding of different perspectives and communities, but rather to acknowledge that "while the uneven flow of cultural material across national borders often produces a distorted understanding of national differences, it also represents a first significant step toward global consciousness" (Jenkins 2006, 170). In this case, the global consciousness is suggested by the experiences of those who described a type of self-discovery or transformative-journey narrative through embarking upon the Kiki media pilgrimage.

[11.4] What makes the fans' richly contested and celebrated experience of the Ross Bakery significant is that it involves physical places and locations being the catalyst and building blocks for fan fiction–type work. In this case it is expressed not through fan fiction stories or staged photographs but through the genre of visitors' comments in guest books. What I have analyzed here, then, are the ways in which the manipulation and integration of the Kiki story and characters into the Ross Bakery by fans provide a rich but contested scaffold for the Kiki fan's media pilgrimage and reveals a creative process where fans transform existing elements of popular culture through their physical surroundings to express changes in culture, geography, and identity.