1. Introduction: Fangirls in refrigerators

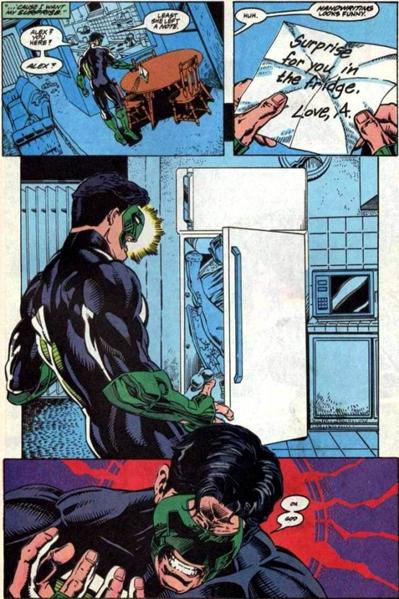

[1.1] In 1999, Gail Simone created a list of the disproportionate number of "superheroines who have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator" (1999a). As for the wives and girlfriends of superheroes who suffered similar tortures in their decades as damsels in distress, Simone dismissed that as "a whole 'nother problem" (1999b). The title of the list, and the Web site it inspired, refer to Green Lantern #54 (1994) (figure 1), in which the hero's girlfriend, Alex DeWitt, is left dismembered in his refrigerator by villain Major Force (note 1). While the implied violence of the image is unsettling enough, its domestic context and paternalistic tone ("Least she left a note") collectively send a clear message about both the role of women in comics and in comic book culture. The panel is wholly focused on Kyle Rayner's reaction to the discovery of his girlfriend's body, visually composed to emphasize his trauma while obscuring hers. One could argue that this panel is simply a textbook example of comics' expressionistic effects and subjective use of color to convey Rayner's horror, but it also aesthetically symbolizes the concerns that underpin Simone's list (McCloud, 1993). Female comic book readers, like Alex Dewitt or many of the other heroines they identify with, often fade into the background or are obscured from view.

Figure 1. The inspiration for Simone's "Women in Refrigerators" list, Green Lantern #54 (1994). [View larger image.]

[1.2] In the years since the Women in Refrigerators list was published, Simone has become one of the most visible female creators of mainstream superhero comic books, perhaps best known for her work on superheroine-centric DC Comics titles Birds of Prey and Wonder Woman. Since coming to comic book fandom's attention with the Women in Refrigerators list, Simone has also been a vocal advocate for women in comics, reiterating the list's initial goal: "My simple point has always been: if you demolish most of the characters girls like, then girls won't read comics. That's it!" (1999c). The primary issue for Simone, one that is echoed by many female comic fans, is not just that there are fewer female superheroes (and thus, when they are brutally dispatched or disregarded, their absence leaves a greater demographic hole in the roster of mainstream superhero comics), or that they are often treated as spin-off franchise "baggage" (Batgirl, Supergirl), but what their treatment implicitly suggests about the comic industry's valuation of female readers. Simone ruminates on the impact of comics' implied or intended audience in the site's "Possible Motives" section, acknowledging that statistically, women are understandably "of marginal import" in a medium dominated by male creators and consumers. Simone concludes that, beyond the potential hostility these representations might breed for women venturing into their LCS (local comic shop or store), what is more disheartening is that "there's a feeling of inconsequence, of afterthought, to these stories" (1999b). This essay examines this nagging feeling of inconsequence, and how female comic book creators and fans have visibly and vocally begun to challenge the representations and industrial inequities that perpetuate these feelings.

[1.3] The years 2011 and 2012 were marked by increased attention to the place and perception of women within comic book culture, from the pointed questions of the "Batgirl of San Diego" at Comic-Con in July 2011 to the publication of Womanthology in March 2012. The increased visibility of these issues can be credited in part to social media platforms like Twitter, a growing network of feminist blogs devoted to geek culture, and the emergence of crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter. However, this groundswell of criticism must also be viewed as a part of broader contemporary debates around misogyny within male-dominated media subcultures. Running parallel to this interrogation of gender and comic book culture, female gamers have begun to document the exclusionary practices and harassment they face within video game subcultures (see the blogs Not in the Kitchen Anymore; Fat, Ugly, or Slutty; Go Make Me A Sandwich). In particular, the vitriolic response to feminist blogger Anita Sarkeesian's Kickstarter campaign to produce a series of critical videos documenting representational tropes of women in video games made national news. Responding only to the project's Kickstarter description, male gamers launched a comprehensive campaign of harassment, including the creation of a Flash-based "game" in which players could physically abuse Sarkeesian (Sarkeesian 2012). This is an extreme case, but it speaks to long-percolating tensions within these communities and increased efforts to maintain "authenticity" and to socially police subcultural boundaries, frequently along gender lines. Comic books and video games, arguably the two media forms most associated with an overwhelmingly male consumer base, also appear be to most concerned about retaining their subcultural capital as geek culture moves from the margins to the mainstream. As the analysis below suggests, events like DC's massive "New 52" rebranding and reboot have provoked criticism from female fans precisely because they presented an explicit (and ultimately missed) opportunity to acknowledge minority readerships and expand comics' fan base.

[1.4] I don't mean to suggest that the comic book industry treats female fans as brutally as it occasionally treats its female heroes, but rather that female fans of comic books have long felt "fridged," an audience segment kept on ice and out of view. Through a brief survey of existing scholarship on comics' readership, a closer examination of several of the controversies that have reignited debates around the latent sexism of comics, and examples of transformative and critical interventions currently being made by female comic book fans, this essay aims to interrogate the politics of (in)visibility for women within comic book culture.

2. Gendering comic book fandom: A survey of scholarship

[2.1] In many cases, we need look no further than the titles of scholarly work on US comic book culture to see how this body of literature reinforces the cultural presumption that comic book fans are overwhelmingly, if not exclusively, male (see Jean-Paul Gabilliet's Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books; Gerard Jones's Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book; Matthew J. Pustz's Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers). There are two primary issues with the current body of literature on comic book culture. First, historical data on comic book audiences are both limited and inconsistent, often relying on "imperfect indicators" such as market studies and reader surveys (Gabilliet 2010, 191). If, as Gabilliet suggests, a fuller understanding of the volume and composition of comic book readership is essential, in part because a medium's "visibility is closely correlated with legitimation" (191), then female comic book fans' recent efforts to make themselves visible as a market segment suggests a similar desire to legitimate their identities as comic book fans. Second, comics scholarship often essentializes women's taste in comics along gendered genre lines, at the expense of engaging with the (admittedly small, but robust) female audience for mainstream superhero comics. The brief survey of scholarship on comic book fandom and readership below suggests a desperate need for more extensive ethnographic and demographic work that addresses how gendered presumptions impact our cultural conception of the audience for comic books.

[2.2] In his history of the creators and publishers of early superhero comics, Jones succinctly characterizes comic book fans as "overwhelmingly male, mostly middle class, mostly Anglo or Germanic or Jewish, and mostly isolated" until they discovered comic book fan clubs (2004, 33). More specifically, Jones pejoratively depicts comic book fanboys as a collective of Jerry Siegels: small, anxious, withdrawn, and terrified of the opposite sex (26–28). Jones also notes that, like Siegel's writing, the stories that comic fanboys "loved and wrote were locked in boyish latency, often lacking females entirely; even the occasional damsel in distress tended to be...fairly sexless and unthreatening" (34). Keeping these descriptions of comic book readers' "boyish latency" in mind, comics scholars typically frame age, rather than gender (or race, or sexuality, or class) as the structuring demographic rift within comic book fandom (Pustz 1999, 164–65). As a result, gender is often invoked and quickly dismissed as an analytical axis, citing surveys that estimate that men constitute 90 to 95 percent of the fan base for comic books (Brown 1997; Parsons 1991; Lopes 2009). Invoking these data without any further interrogation allows these studies to focus on society's historically "paternalistic attitude" (Brown 1997, 18) toward comic book fanboys while neatly sidestepping conversations about the patriarchal attitude of comic book culture.

[2.3] For example, Jonathan David Tankel and Keith Murphy's ethnographic study of comic book collectors states that "the most striking and expected demographic characteristic of the comic book collectors surveyed is that 100 percent are male" (1998, 60). Modeled on the questionnaire used in Janice A. Radway's Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature, Tankel and Murphy's survey group was small (only 38 out of 50 questionnaires were returned, some of them incomplete), making their certainty regarding these extrapolated, "expected demographic" results especially problematic. Tankel and Murphy reinforce their own expectations with industrial and anecdotal evidence to argue that the "overwhelming male dominance" of comic book fandom "remains true despite the efforts that all the major publishers put into winning the readership of females" (1998, 60–61). In this and many other studies, comic book fandom and culture is coded as always completely male, and the comic book industry's failure to acknowledge the female audience is justified through economic rationalization. In comic books' Golden Age, at the height of its popularity as a mass media form in the 1940s, comics were equally popular with adolescent and preadolescent boys and girls (Gabilliet 2010). Though we must also be skeptical of data estimating that 80 to 90 percent of girls ages 6–17 were reading comics around 1944 (Parsons 1991, 69–70), the current discursive construction of women as a surplus audience obscures the fact that they were a preexisting segment of comic books' audience at a time when comics consumption wasn't as stringently gendered. Scholarly accounts of comic book publishers' attempts to reach out to female readers and expand their current fan base tend to stress that these attempts invariably fail (Pustz 1999), with minimal examination of why.

[2.4] The issue is not simply that popular and academic literature generally renders female comic book readers invisible; it is also that the moments in which they are visible, they are too frequently compartmentalized and contained. Whether addressing the boom of romance comic books in the postwar period (Lopes 2009), or contemporary transmedia extensions designed to expand a comic book's preexisting male fan base (Jenkins 2007), the gendered genre discourses used to frame past and present industrial efforts to reach out to female readers are problematic on two fronts. First, postwar romance comics, written predominantly by men, featured female protagonists but continued to frame them exclusively through their relationships to men, championing domestic servitude and illustrating the "perils of female independence" (Wright 2001, 128). Likewise, transmedia comics like Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane may have the capacity to nuance female characters that have previously functioned as love interests and/or plot devices and to tell stories from their point of view, but the series' essentialist emphasis on romance (reflected in both form and content) keeps it firmly located in the "pink ghetto" (Radway 1984, 18). Second, and even more troublesome, is the fact that Spider-Man Loves Mary Jane is clearly marked as existing outside of Marvel continuity. Thus, while it might offer new readers a low-stakes access point into the Spider-Man canon, it also cordons off these new presumed female readers from the broader continuity traditions, serial pleasures, and community of comic book readership.

[2.5] When not addressed through "feminine" genres, female comics audiences are most frequently aligned with independent comics (Pustz 1999). As Trina Robbins (2002) and others have noted, female readers frequently gravitate toward indie titles in part because this is where the vast majority of female comic book writers and artists are working. Courtney Lee Weida notes that the tendency to feminize indie comics, "if feminizing means the inclusion of women's agency as producers of cultural narratives in male dominated narrative artforms" (2011, 103), aligns indie comics with zine culture and other spaces in which activist self-publishing is valued. Many scholars have acknowledged that underground comix culture, despite its typically progressive political leanings, was equally laced with misogyny (Lopes 2009; Pustz 1999). Still, we can see the traces of the DIY ethos behind the underground comix movement and its mobilization as a feminist strategy in publications like Wimmin's Comix in the 1970s (Noomin 2004), within the contemporary transformative projects discussed below.

[2.6] Research on female audiences for mainstream superhero comics is limited, in part because of a lack of transparency from publishers who, when they do conduct surveys, do so to "maximize profits within the existing system, rather than seeking to extend the readership of comics across barriers of sex, age, and race" (Gabilliet 2010, 207). Most recently, DC hired the Nielsen Company to gauge the demographic response to the New 52, finding that the relaunch ultimately "galvanized the traditional fan base for superhero comic books: male readers, who were already—or have at one time been—comic book fans" (DCE Editorial 2012). The data culled from over 6,000 surveys conducted in comic stores, via e-mail and online, between September 26 and October 7, 2011, found that 70 percent of the respondents were already avid comic book fans, and 93 percent were male. The fact that only 5 percent of those surveyed indicated that they were new to comics should have been a point of concern for DC; instead, it was widely read as an affirmation "that [DC's] best bet for solvency in the market is to focus exclusively on keeping the 18–34 year old male reader to the exclusion of other demographics, over the protests of many female fans and readers" (Polo 2011). Comic blogger Jill Pantozzi echoed Gabilliet in her response to DC's explicit efforts to target men of ages 18–34 with the relaunch, noting with some frustration that the "survey wasn't meant to tell DC what they were doing wrong or what they could do to get more women to read their books (even though many respondents absolutely told them in the space provided). All the survey proves is that [DC's] lack of trying to do anything to gain a female audience did exactly what was expected—nothing" (2012b).

[2.7] Contrary to the results of the Nielsen DC survey, anecdotal evidence suggests that the female readership for comics has been growing over the past decade, in part because of comics' integration into transmedia storytelling models. Reflecting on the noticeable shift in comic book convention attendance over the past several years, Gail Simone recounted an exchange between her husband and a male attendee at a recent convention. While signing books for female fans, noticing female attendees lined up to meet male creators and flocking to booths featuring creators like Amanda Connor, Simone marveled that despite being in "the very epicenter of that, the young man turned to my husband and said, 'I don't care what anyone says, women are never going to read comics'" (2012, 17). What female comic book readers must fight for now, Simone suggests, is acknowledgment, in large part because those in power "don't see what's directly in front of them" (2012, 17). The next section frames this visibility problem through the allegorical capacity of "Invisible Girl" Sue Storm and the gendered politics of studying subcultures.

3. The politics of invisibility (from Sue Storm to subcultural theory)

[3.1] Marvel's The Fantastic Four debuted in 1961 as a superhero narrative focused on the often dysfunctional familial bond among its characters. Given this historical context and the comic's emphasis on how the "problems of human existence interfered with their crimefighting abilities" (Genter 2007, 954), it is difficult to read symbolic matriarch Susan "Sue" Storm (Invisible Girl, later Invisible Woman) outside of the context of second-wave feminism. Wife to Reed Richards (Mister Fantastic), sister to Johnny Storm (the Human Torch), and colleague/caretaker to Ben Grimm (the Thing), Sue's power, her ability to turn herself invisible, could be read as a commentary on the shifting cultural visibility of women's rights in the 1960s. Laura Mattoon D'Amore (2008) has suggested that Sue Storm symbolically represented the 1950s suburban housewife, "undercompensated and unrecognized for her successes," invisible and "unappreciated in a world of and for men." Tracing these tropes within The Fantastic Four comics through the 1960s, D'Amore argues that Sue's invisibility is both literal and figurative, initially mirroring and ultimately deflecting the period's gender norms.

[3.2] D'Amore locates this shift from reflection to deflection in 1964's The Fantastic Four #22, in which Sue learns to craft powerful force fields, remaining visible as she projects invisibility onto others. As D'Amore (2008) notes, this "appears to be a limitation—yet another weakness—but in actuality it is critical to her newer, stronger identity. This power privileges her visibility, rendering others (men included) invisible." Thus, though not intentionally constructed as a feminist character, Sue Storm's visibility might be read as a "classic feminist victory," finally positioning her as an equal member of the team. Just as fans advocated for a more empowered Sue Storm in the letter columns of The Fantastic Four in the early 1960s, contemporary comic book fans are becoming increasingly unwilling to accept comic book culture as a world of and for men. We cannot neatly equate visibility with equality; nor should we fail to interrogate the problems and paradoxes surrounding notions of "visibility politics." It is important to acknowledge the enduring centrality of the concept not just to feminist media criticism but to a range of scholarly work on marginalized communities.

[3.3] In their seminal 1977 essay "Girls and Subcultures," Angela McRobbie and Jenny Garber interrogated the absence of female subjects from the literature emerging from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University. McRobbie and Garber's ultimate concern, that "girls sub-cultures may have become invisible because the very term 'sub-culture' has acquired such strong masculine overtones" (1993, 211), could easily be applied to contemporary concerns about the masculine overtones of "comic book culture." This gendered invisibility is cultivated and sustained through a variety of journalistic, industrial, and academic discourses. Though media fandom in general has moved out of the subcultural shadows within convergence culture, McRobbie and Garber's claim that the "popular image of a subculture as encoded and defined by the media is likely to be one which emphasizes the male membership, male 'focal concerns,' and masculine values" (1993, 212) remains firmly entrenched within comic book fandom.

[3.4] In an effort to explain why girls were rarely the subject of subcultural studies, McRobbie and Garber observed that girls are likely to retreat or, alternately, become collectively aggressive in situations that are "male-defined" (1993, 210). Many female comic book fans have adopted a similar response to the male-defined realm of comic book culture, in which "both the defensive and aggressive responses are structured in reaction against a situation where masculine definitions (and thus sexual labeling, etc.) are in dominance" (210). Joanne Hollows has made a similar argument about cult movie fandom, a subculture that is not only "based on a refusal of competencies and dispositions that are culturally coded as feminine; it may also work structurally to exclude women from participation" (2003, 37–38). Comic book fandom, like cult movie fandom or other male-dominated subcultures, may welcome women if they "opt to be 'one of the boys,'" but this fails to "challenge the power relations which sustain a position in which there are few opportunities to capitalize on femininity" (40) as either a producer or consumer. Thus, it is not enough to be visible; it is the terms and conditions of that visibility that are central.

[3.5] My own concerns regarding comic book fangirls' relative invisibility, as a demographic and as a subject of study, echo McRobbie and Garber's anxieties that this might create a "self-fulfilling prophecy, a vicious circle" (1993, 212) in which women view comic book culture as inaccessible or inhospitable. For example, scholars tend to characterize the LCS, the primary site in which comic book fandom is made visible, as a space reminiscent of a secret clubhouse with policed social barriers of entry for new readers, and in particular female readers. Benjamin Woo's recent work productively describes the social setting of the LCS, and the tensions they exhibit "as both 'sanctuaries' from mainstream hierarchies of taste and status, and arenas of competition for social and subcultural capital" (2011, 125). Building on Erving Goffman's distinction between "front" and "back" regions of theatrical performance, Woo allegorically links the inside of an LCS to a backstage area of a theater, a safe and supportive space free of the cultural scrutiny of an audience. Though he characterizes the LCS as a backstage area in which comic book readers aren't forced to manage impressions or perform mainstream taste hierarchies or social norms (131–32), Woo acknowledges that "a region's 'frontness' or 'backness' is relative to the performers and audiences in question" (2011, 132).

[3.6] When women are mentioned as inhabitants of the subcultural space of the LCS (either in scholarly or conversational accounts), they tend to be framed as highly visible precisely because of their pervasive framing as subcultural interlopers. In this panoptic model, visibility is not desirable but rather a trap that induces a "state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power" (Foucault 1995, 201). This has not been my personal experience as a patron of comic book shops, and gender rarely enters Woo's ethnographic account of the two social regions that LCS patrons occupy. Still, the notion that women might be simultaneously subjected to the front region's pressure to performatively manage impressions and be scrutinized by the audience (in this case, male patrons, as well as, frequently, shop owners and staff), and denied the invisibility afforded by the back region as a space for performers/fans to let down their guard and collectively engage in conversation and social rituals, is often reinforced in the characterization of comic book shops (Pustz 1999). Female comic book fans, like Sue Storm, must consider the different and often paradoxical, forms of power that visibility and invisibility afford. If the goal is for female comic creators and fans to become more than an industrial niche or surplus audience, to become invisible (read: accepted) members of that culture, increased visibility will be necessary to encourage that shift.

[3.7] Because comic book culture is male defined, and because this perception has permeated both the collective consumer consciousness and the spaces in which those exchanges take place, it is understandable that many female comic book fans have taken it upon themselves to construct alternative, fangirl-friendly spaces. Henry Jenkins has argued that a "politics of participation starts from the assumption that we may have greater collective bargaining power if we form consumption communities" (2006, 249). The fact that Jenkins's example of such a community is Sequential Tart, a Web zine and community that was formed in 1997 as "as an advocacy group for female consumers frustrated by their historic neglect or patronizing treatment by the comics industry" (249), is evidence that the medium of comics is perhaps most in need of such a politics of participation. In addition to other organizations with similar advocacy goals, such as Friends of Lulu, the boom in recent years of blogs that resonate with Sequential Tart's mission, such as DC Women Kicking Ass, The Mary Sue, Girls Read Comics Too, and Has Boobs, Reads Comics, among many others, is heartening. Even more encouraging is the politics of visibility that has recently emerged around and through these consumption communities, which have been wielded as weapons of intervention in the gender and comics debate.

4. Form and feminism (or, why we care how Mary Jane drinks her coffee)

[4.1] The increased visibility of female comic book fans in 2011 and 2012 was due in large part to a string of compounding controversies that prompted an outpouring of criticism and commentary online. As Simone's initial Women in Refrigerators list makes clear, debates surrounding the links between comics' representation and readership are not new but have been revived with renewed interest amid broader conversations about women in comic book culture and comics' industrial survival. This section briefly discusses three notable firestorms of 2011: the Batgirl of San Diego, the response to hypersexualized female characters in the New 52, and the Mary Jane Drinks Coffee meme. Importantly, these three controversies suggest that comic book fans are increasingly producing transformative commentary, turning the male gaze of comic book culture back on itself, and holding the industry accountable for the paltry number of women being hired to work on mainstream superhero titles.

[4.2] At San Diego Comic-Con 2011, a woman dressed as the Stephanie Brown iteration of Batgirl attended a range of DC Comics panels and waited patiently in line to ask a question of the overwhelmingly male panelists. Considering that the majority of these panels were expressly designed to promote the launch of the New 52, the questions themselves were not particularly controversial. They were questions about creators, which heroes would be featured, and comments on leaked covers and promotional images online. What was controversial was that each of these questions cordially, but pointedly, asked DC creators and publishers to explain the lack of female characters and creators being featured in DC's reboot. It is important to acknowledge that this fangirl, quickly dubbed the "Batgirl of San Diego" and now known by her handle, Kyrax2, wasn't the only attendee to interrogate the noticeable shift in the demographics of DC's creative teams surrounding the new line, with female creators dropping from approximately 12 percent to making up only 1 percent of DC's talent roster. One sound bite that circulated widely featured a male fan posing a similar question, only to be testily challenged and ultimately silenced by DC copublisher Dan DiDio.

[4.3] Ironically, the originator of the Women in Refrigerators list now frequently serves as a tokenist example of publishers' efforts to support female creators. As arguably the most prominent female writer for DC Comics, publishers and fans' frequent reliance on the "Gail Simone defense" when confronted with the aforementioned statistics makes tactical sense (in other words, if Simone, a vocal critic of gender and comics, chooses to align herself with DC and is known to craft narratives centered around compelling female characters, then the industry clearly doesn't have a gender bias) but ultimately only highlights industrial inequities. In particular, Simone's attachment to the New 52's Batgirl reboot suggests that her visibility as a female comic creator and critic is a double-edged sword. Though female fans were certainly pleased that Batgirl was getting her own title, many were disappointed to learn that Simone would be relaunching the character of Barbara Gordon as Batgirl, effectively erasing Gordon's tenure as Oracle after being paralyzed by the Joker in Alan Moore's Batman: The Killing Joke (1988). In the New 52's Batgirl, Barbara regains the use of her legs three years after being shot by the Joker, and quickly slips back into the cape and cowl. While rebooting characters has been a common strategy of the New 52, many fans felt that the decision smacked of ableism and were especially critical of Simone, who as a feminist creator was expected to be more sensitive to these representational shifts and their impact on minority readerships.

[4.4] If Simone's industrial presence has become somewhat symbolic, invoked to quickly dispel criticism of industrial inequities (note 2), what made the Batgirl of San Diego such a powerful symbol was her consistent, visible presence at DC's panels, the persistence of her questions, and other fans' response. In response to the Batgirl of San Diego, Laura Sneddon (2011) of comicbookgrrrl.com observed:

[4.5] Typically, questions about women in comics from women in the audience were prefaced with the usual disclaimers—"I mean absolutely no malice," "I don't want this question to come across as confrontational"—in full knowledge of the likely reaction. That the rest of the audience booed and heckled these women is, sadly, no big surprise. You only need turn to any large online comics forum to see a slew of (mostly male but not all) comic fans condescendingly dismissing women's concerns about female diversity in comics. In a society where pop culture is very much dominated still by men, and the male gaze, it is very easy for our concerns to be brushed aside.

[4.6] Unquestionably, the Batgirl of San Diego's unwillingness to be treated as a surplus reader challenged widespread presumptions about superhero comic book readership, but she also exposed the gendered nature of Comic-Con as a space. Doreen Massey has argued that spaces and places are not only gendered but also "reflect and affect the ways in which gender is constructed and understood," noting that attempts at spatial control can extend to a social control of identity (1994, 179). Fan conventions have historically been characterized as safe, even utopian spaces in which differences are embraced. My work on the Twilight protests at San Diego Comic-Con 2009 (Scott 2011), the recent sexual harassment debacle at Readercon 23 (Colby et al. 2012), and comic book artist Tony Harris's November 2012 Facebook screed against "COSPLAY-Chiks [sic]" who "DONT [sic] KNOW SHIT ABOUT COMICS" (Dickens 2012), all indicate that these utopian characterizations of comic book conventions belie how gendered subcultural tensions manifest in these spaces. Specifically, the hostility directed at the Batgirl of San Diego from fans and publishers alike suggests a sort of panopti(comic)con, in which fan expression is increasingly policed. Like the aforementioned panoptic qualities of the LCS, conventions transpose the implied male gaze of comics into physical spaces, realizing John Berger's claim that "Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at" (1973, 47). If female comic fans are simultaneously prisoner and guard, it is in large part because comic book form itself encourages women to "consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman" (Berger 1973, 46).

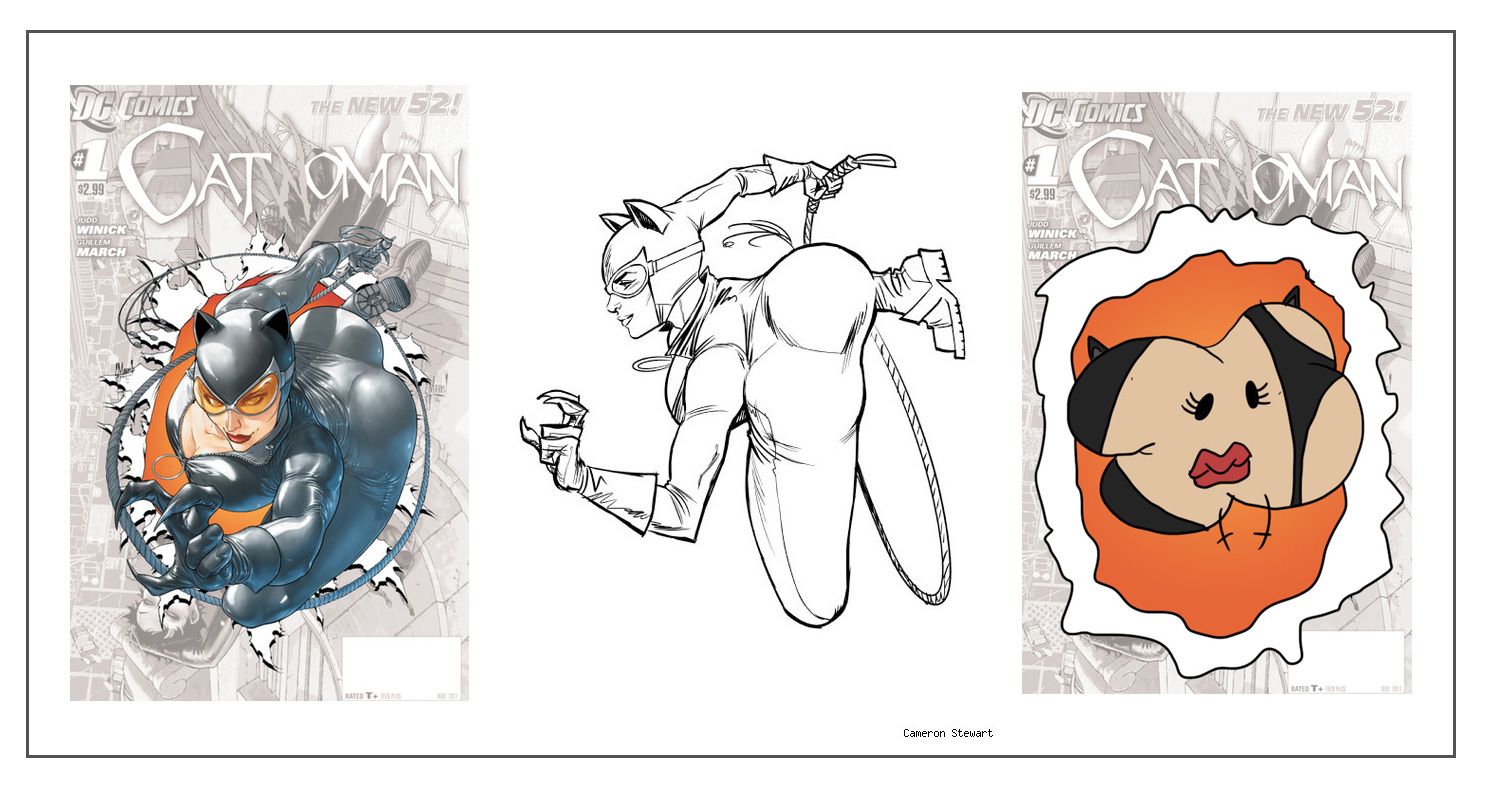

[4.7] The New 52, which presented a prime opportunity to attract new readers and reboot both comic book franchises and the comic book industry at large, instead kept its focus firmly on 18-to-34-year-old men and accordingly kept its superheroines in "outfits that catch the eye and erect the crotch" (Sneddon 2011). Many female comic bloggers argued that it was not simply an issue of costuming, though a wave of cross-dressing and genderswap memes accompanying the New 52's release made these disparities abundantly, and comically, clear (note 3). To the male comic book fans who frequently rationalized or openly dismissed complaints about the representation of women in comics by noting that the male superhero body is hypermasculinized, these female bloggers argued that "the 'ideal' nature of male superhero bodies will always focus on strength and fitness while the 'ideal' nature of female superhero bodies will always focus on sexiness and vulnerability" (Sneddon 2011). In particular, Guillem March's cover image for Catwoman #0, one of the only female-centric titles in the relaunch, was criticized and endlessly parodied (RoboPanda 2012) for exhibiting the "broken back" syndrome that many superheroines aesthetically suffer from (figure 2).

Figure 2. The controversial cover of the New 52's Catwoman #0, and two example of the many parodies of Catwoman's "broken back" pose by Cameron Stewart and Josh Rodgers. [View larger image.]

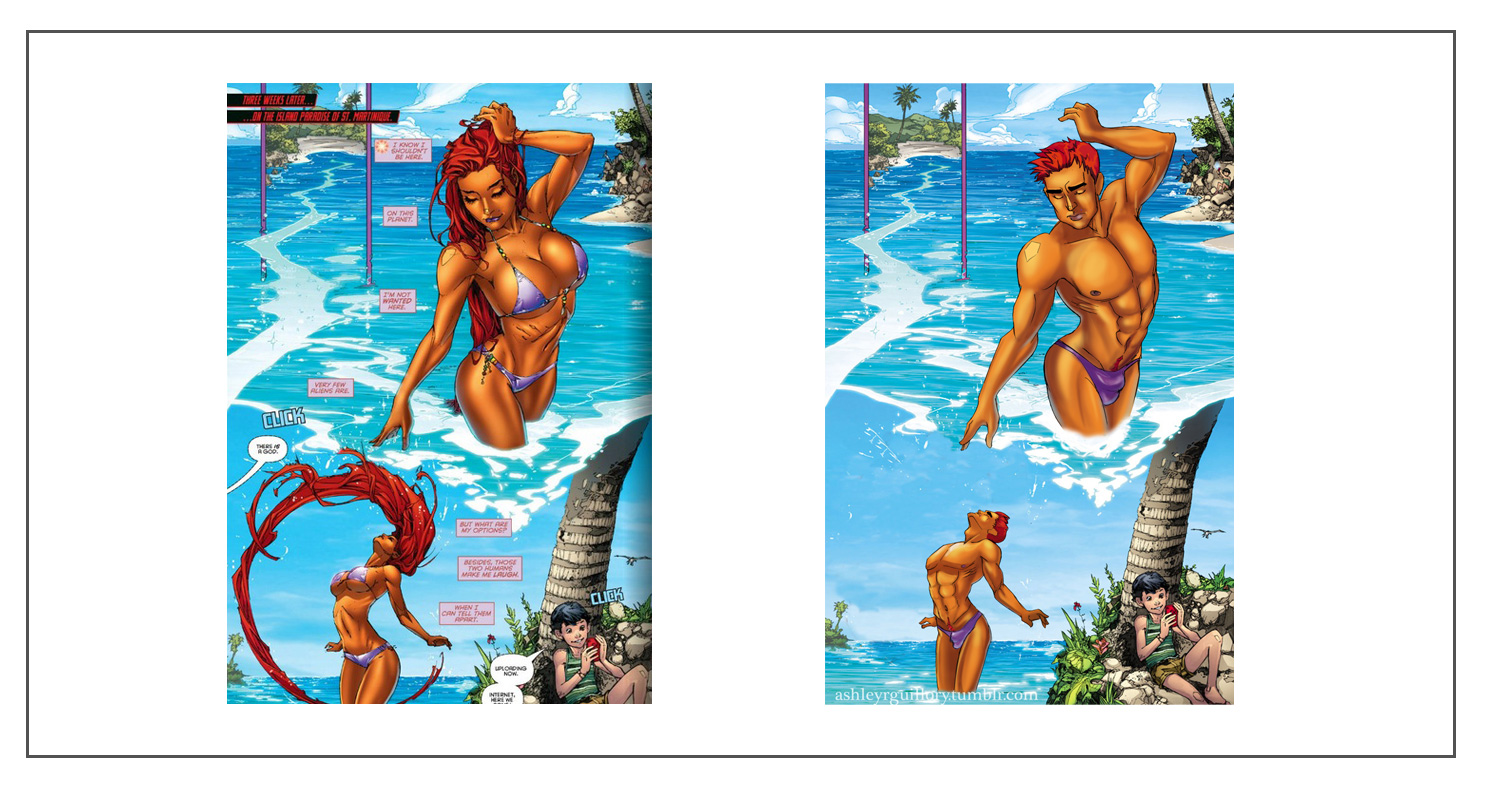

[4.8] Starfire's appearance in Red Hood and the Outlaws also drew attention and genderswap criticism (figure 3), in that her presence in the comic was little more than a pornographic tableau. Reflecting on the aspirational nature of superhero comics and what precisely Catwoman and Starfire were asking female readers to aspire to, Laura Hudson (2011) asked a common question and arrived at a common answer: "Why is she contorting her body in that weird way? Who is she posing for, because it doesn't even seem to be Roy Harper? The answer, dear reader, is that she is posing for you. News flash: Starfire isn't being promiscuous because this comic wants to support progressive notions of gender roles. Starfire is being promiscuous so that you can look at [her]." It is difficult not to hear John Berger in Hudson's remarks, particularly the notion that, under these conditions, a woman's "own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another" (1973, 46).

Figure 3. Ashley R. Guillory's "Manfire," a prime example of how artists have used genderswapping to transformatively critique comic book representation. [View larger image.]

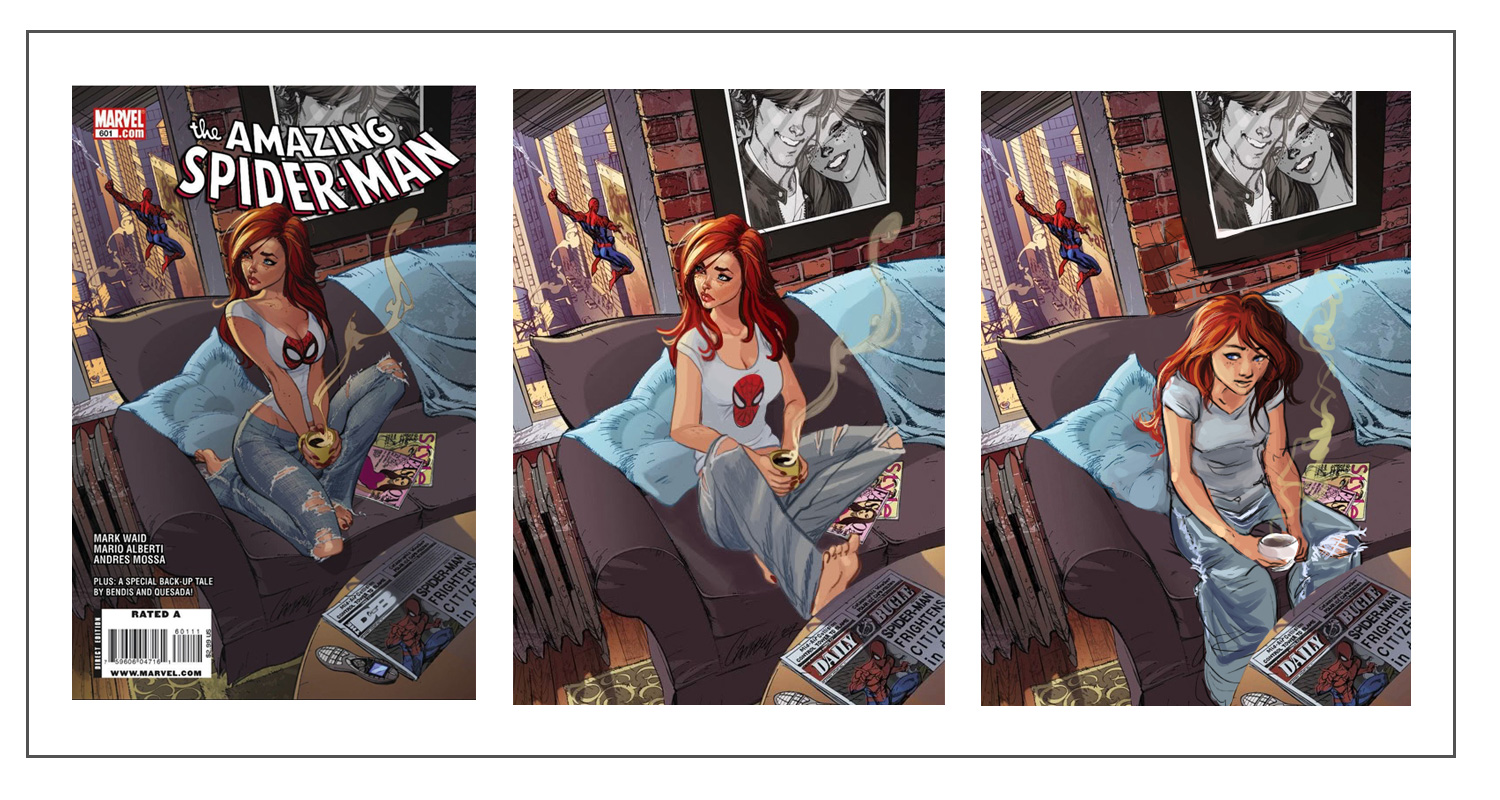

[4.9] In the midst of growing complaints about the objectification of female superheroes in the fall of 2011, a meme emerged mocking the cover of The Amazing Spider-Man #601 (2009). J. Scott Campbell's cover image, depicting Mary Jane Watson fretting about Spidey's safety over her morning coffee, provoked a string of parodic images in which fans attempted to contort themselves into Mary Jane's pose (Sicha 2011). The backlash also prompted artists to rework the image, sometimes in radically different styles, but more often than not hewing closely to the original cover, arguing that minor alterations were enough to make the image more relatable without sacrificing Mary Jane's sex appeal (figure 4). One commenter summarized these frustrations: "Look, I get it. Mary Jane is hot, but for Christ's sake, this is why girls feel alienated from comics. This is not how a human lounges. [...] This is what we're talking about when we say 'male gaze'" (werockthisshit in kitfoxhawaii 2011). Because Mary Jane is presumably alone in her apartment, the performative pose assumes "the determining male gaze" of a heterosexual comic book reader projecting his fantasies on the female form. Mary Jane, like the Hollywood actresses in Mulvey's initial study, is thus "styled accordingly...simultaneously looked at and displayed, with [her] appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that [she] can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness" (Mulvey 1999, 837).

Figure 4. J. Scott Campbell's original cover of The Amazing Spider-Man #601, and two covers that attempt a more realistic depiction of Mary Jane (artists unknown). [View larger image.]

[4.10] Though it is clearly popular to channel Laura Mulvey in these critiques of the male gaze of mainstream comic book art (and perhaps comic book culture by extension), a 1979 interview with science fiction author Samuel R. Delany in Comics Journal is quick to differentiate between the respective gazes of film, television, and comics. Privileging the gaze of comics over other media forms, Delany cited the unprecedented control the medium offers: "Viewers can control the speed their gazes travel through the medium, they can control how far away or close they hold the page, whether they go backwards and regaze—and going back in a comic book is a very different process from going back in a novel to reread a previous paragraph or chapter" (1979, 40). Arguing that the nature of the medium renders the reader a "coproducer" of the text, Delany's notion of the "regaze," while compelling, doesn't address the issue that women are rarely considered in these terms. Thus, despite comics' great potential, they still fall prey to many of the same issues Mulvey identified with respect to film, and perhaps exacerbate the male gaze via this gendered control of the regazing and the bodies of female superheroes. This unprecedented control of the gaze also evokes the panoptic power of the prison guard, with superheroines arranged in their panels/cells, performing this state of constant visibility for an invisible male spectator.

[4.11] In the letters column of Saga #4, writer Brian K. Vaughn shared the results of a tongue-in-cheek reader survey he had placed in the prior issue. Having requested readers to list their age, Vaughn noted that 35 percent of the respondents made a point of identifying themselves as women, despite the fact that he hadn't directly solicited gender demographics. While this is not entirely surprising, given Vaughn's reputation for producing work with compelling female characters and feminist undertones (Y: The Last Man, Runaways, Ex Machina) and the large female fan base that artist Fiona Staples brings to the project, the fact that these respondents felt compelled to specify their gender is telling. The growing desire for women to be counted, or rendered a visible part of the comics fan base, and the industry's reticence to listen have resulted in crowdfunded endeavors. These projects strive to rectify some of the aforementioned representational inequities and prove there is a paying audience for more progressive female superheroes; but centrally, they are concerned with making female comics creators and fans visible on their own terms.

5. A transformative intervention: The case of Womanthology

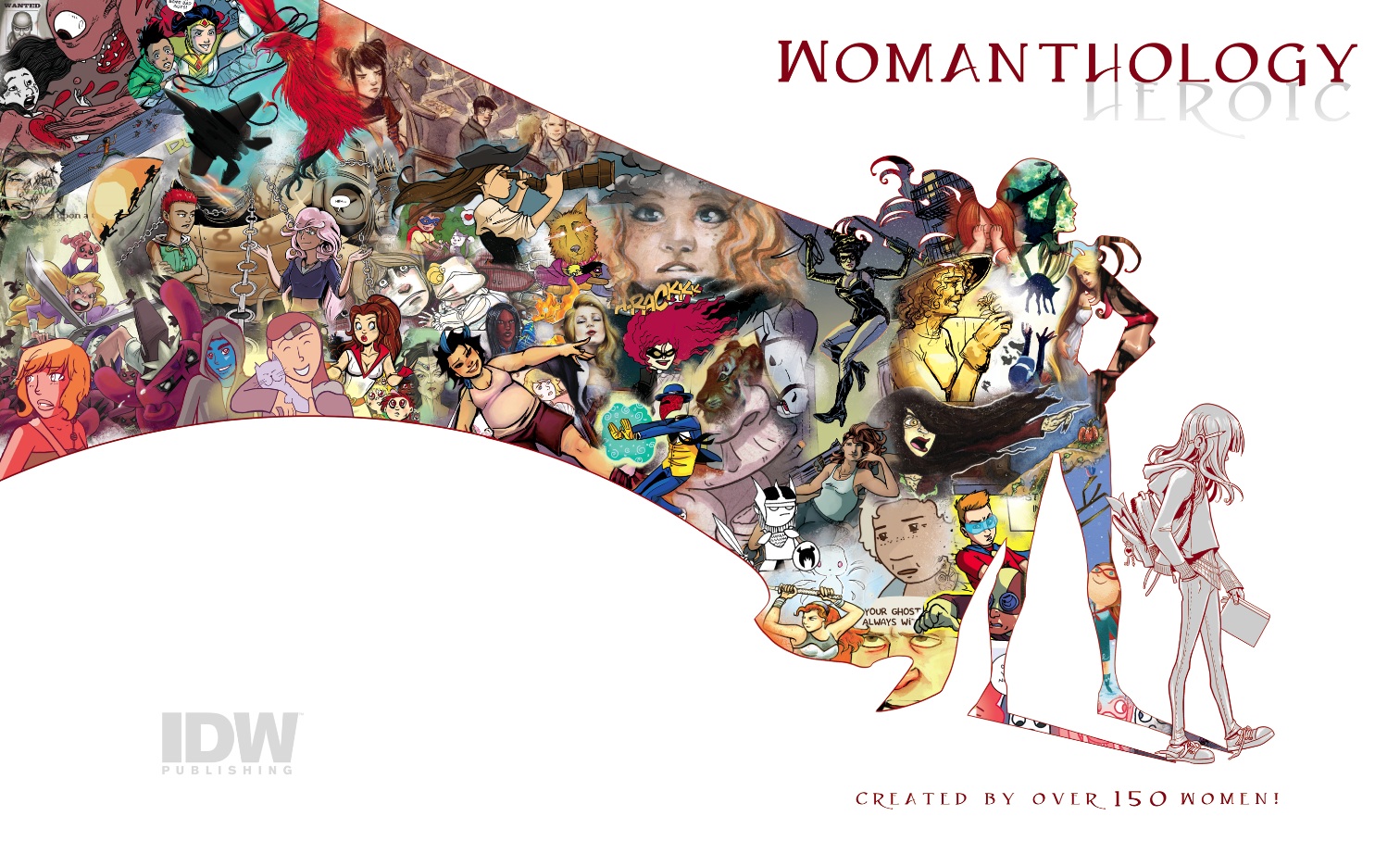

[5.1] In May 2011, in the wake of controversies surrounding DC's New 52 and various other calls from female comic fans to be acknowledged as both producers and consumers, artist Renae De Liz tweeted and pitched the notion of a charitable comic anthology created entirely by women. A little over one month and one hundred contributors later, a Kickstarter page was created to raise $25,000 for printing costs, with IDW Publishing supporting the release. After surpassing the initial fund-raising goal in less than 24 hours, Womanthology: Heroic went on to raise over $109,000, becoming one of the most successful crowdfunding endeavors in the history of Kickstarter. Though there has been some debate surrounding the project's charitable giving and distribution of funds (Khouri 2011), the anthology was successful enough to prompt IDW to commit to a five-issue Womanthology: Space miniseries, which launched in September 2012. This miniseries furthers the project's initial goal of carving out a space for female comic book creators to share their work, but it also demonstrates the potential of projects like Womanthology as a transformative industrial intervention.

[5.2] I don't use the word transformative here as we might when discussing fan works (that is, fan fiction or other texts created by fans and inspired by a media property), in part because Womanthology features wholly original works. So rather than framing Womanthology as a textually transformative work that, in the Supreme Court's terms, "adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message" (Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music Inc. 1994), I would categorize it as an industrially transformative work, one that strives to effect the same change on the comic book industry that a fan might on a media property, bending it to align with textually unacknowledged identities and desires and wielding it as a mode of critical commentary. Womanthology: Heroic is thus pointedly the antithesis of a monthly comic book, weighty in both size and mission, distancing itself from the pejorative implications of the "floppy" and its historic treatment, often mistreatment, of female creators, character, and consumers. Though diverse in genre, style, and tone, the comics thematically coalesce around and interrogate our culture's narrow, often rigidly gendered, definitions of heroism. As the cover image indicates (figure 5), many of the comics feature preadolescent and adolescent girls as protagonists, visualizing an untapped market key to the industry's future survival and articulating textual and aesthetic frustrations with mainstream comics.

Figure 5. The cover of Womanthology visualizes the range of stories and styles that remain underrepresented in mainstream comics. [View larger image.]

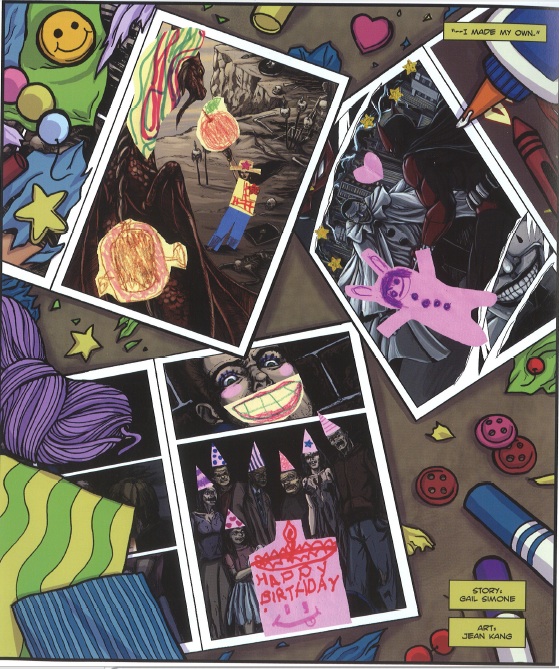

[5.3] Gail Simone and artist Jean Kang's contribution to the collection, "In Every Heart a Masterwork," exemplifies these tropes and celebrates the transformative drive of female fans. Focused on a precocious young girl who pilfers and "fixes" her big brother's violent, hypersexualized comic books, "In Every Heart a Masterwork" models how fannish frustration can prompt creative intervention. Following a triptych in which the young female protagonist rifles through her brother's comics (notably, the center panel pictures the girl holding up a comic book featuring a busty dragon slayer, "Beastia," as one might a Playboy centerfold), she sets to work with her art kit. The comic closes with the girl's mother offering to buy her daughter "some comics a girl might like," to which the girl replies, "It's okay Momma—I made my own" (figure 6). The image of the transformed comics that concludes the story highlights a range of fannish (and potentially feminist) rewriting strategies, from the reconfiguration of Beastia as a fully clothed cowgirl, to the generic subversion of the zombie comic, to the Mary Sue–ish self-insertion, to the potential slash relationship connoted by the heart placed between two male characters. The celebration of transformative textual play in this particular comic is reinforced by the "Pro Tips" peppered throughout the anthology, expressly designed to encourage readers to create their own comics. These Pro Tips range from practical advice to general words of encouragement, supplemented with in-depth walk-throughs on how to write, draw, ink, color, and letter comics, and interviews with notable female creators on their creative process.

Figure 6. Transformative intervention is foregrounded in Gail Simone and Jean Kang's contribution to Womanthology, "In Every Heart a Masterwork" (2011). [View larger image.]

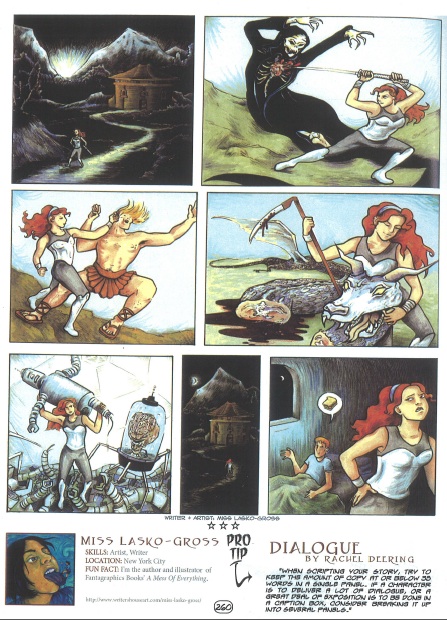

[5.4] Other comics in the collection, such as this single-page untitled comic by Miss Lasko-Gross (figure 7), openly play on gendered notions of visibility, suggesting that even heroics of the highest order might become a form of women's work within our current cultural frame. Across seven dialogue-free panels, Miss Lasko-Gross's heroine slays ghouls, gladiators, dragons, and killer robots, only to return home to a hungry male partner lazing in bed requesting a sandwich. The physicality of the female protagonist clearly plays off of long-standing debates within comic book culture regarding representation. The punch line of the sandwich, and the heroine's response, speaks directly to the weariness of female fans of purportedly masculine properties and media forms being consistently told to "get back in the kitchen." This Internet forum refrain has grown alongside female fans' (particular female gamers and comic book readers) increased efforts to expose and denounce sexism in their respective communities over the past several years (note 4). What Miss Lasko-Gross's comic does so effectively, and so economically, is capture the moment of grudging disappointment that accompanies these regressive dismissals. Many of the comics in Womanthology similarly grapple with gender norms and their social enforcement.

Figure 7. This untitled comic by Miss Lasko-Gross in Womanthology (2011) reframes and reflects on the notion of "women's work" and the common digital dismissal, "Go make me a sandwich." [View larger image.]

[5.5] In some senses, a project like Womanthology can be viewed as an attempt to work through the tensions that invariably accompany discussions of gender, visibility, and fan culture. First, though it primarily focuses on the inequitable gender politics of mainstream comics, it points toward other marginalized or minority voices in comics, including works that consider heroism through the lenses of race, age, and mental and physical ability. As fan culture and fan studies broadly begin to look beyond gender as its primary critical axis to consider other marginalized audiences, the collection's attention to diversity, not just in content and style but in contributor demographics, suggests an attempt to raise the visibility of more than just female comic creators and readers. Second, while the collection shares many of the qualities and core traits of feminine fannish gift economies, Womanthology explicitly pitched itself as a professional launching pad for its contributors. The majority of fan creators show limited interest in industrial exposure, choosing instead to circulate their works for free as a mode of building and maintaining communal bonds. If this mode of feminine textual production remains relatively invisible to those outside these communities of practice, Womanthology's overt effort to exchange free labor for industrial visibility suggests a tentative step toward a reconciliation between commercial and gift economies that retains the appeal of both. Debates around the commercialization of fan labor are ongoing, and the collection's capacity to inject the comic industry with emerging female creators remains to be seen, but Womanthology makes a compelling case for how gendered means of amateur production as an entrée to professionalization (modding, fan filmmaking), might be used to feminist ends.

6. Conclusion: Why the "what" matters

[6.1] A recent In Focus section of Cinema Journal devoted to comics studies culminated in a conversation among scholars Greg M. Smith, Thomas Andrae, Scott Bukatman, and Thomas LaMarre. The aim of this dialogue was to survey the state of the field and contemplate its future as a burgeoning object of study. Discussing the lack of "exemplary" comics scholarship and how the difficulties of navigating a hybrid scholarly identity might contribute to such a lack, Bukatman noted:

[6.2] Younger scholars, many of whom are comic fans, feel that they have to overburden their objects of study with a lot of ideological analysis. So there is a wave of "representations of" studies—African Americans in comics, queer characters in comics, and so on. It becomes a very predictable parade of concerns that played through in other fields decades ago. It also, often, serves to rob these objects of whatever pleasures they may have contained for the very scholars producing the work. But it serves the purpose of separating the scholar from the fan and demonstrating to the home department that the scholar is, indeed, doing "serious" work. (Smith et al. 2011, 138)

[6.3] LaMarre concurred that "rather than grapple with the 'how' of comics, scholars tend to dwell on the 'what' of comics" (Smith et al. 2011, 138), a concern that reflects broader anxieties surrounding the "comics and..." logic that has dominated much of comics scholarship in the age of transmedia storytelling and superhero movie franchises. I am in no way advocating that comic book studies rehash (or worse, be subsumed by) media studies methods and discourses designed to address wholly different media forms. Nonetheless, this essay suggests that comic book culture is currently witnessing a potentially transformative feminist intervention in which the "how" and the "what" of comics are being placed in meaningful conversation. Like Simone's Women in Refrigerators list, which situated a discussion of superhero comics' narrative tropes and representations within broader concerns about the comic book industry and its conception of the audience, what I am calling for is an integrated approach to comic book studies in which discussions of the distinct pleasures of comic form and ideological analyses are not mutually exclusive. At the risk of overburdening LaMarre's comment, I am interested in a future for comic book studies that creates critical intersections between the "how" and the "what" of comics, in addition to considering the "who" (audience) and the "why" (economics/industry demographics).

[6.4] Fan scholars, whether they embrace the acafan portmanteau or not, have been grappling with questions around affect and academia for decades. If, as Bukatman argues, affect is not the enemy of objective, robust scholarship, and that "the fan's stance is the perfect starting point for beginning an analysis: 'This fascinates me—why?'" (Smith et al. 2011, 139), than the expressions of frustration currently emerging from comic book fandom provide an ideal starting point to consider the transformative potential of these conversations and a productive direction (among many) for the growing field of comics studies. Andrae and Bukatman both acknowledge that fans were the first to seriously study comics and that some of the best contemporary comics scholarship is being produced outside of the academy by fan bloggers (Smith et al. 2011). While the analysis above reflects on only a small portion of feminist criticisms currently being levied at the comic book industry by fans, it collectively exposes a need for more scholarship on comic book audiences.

[6.5] Meanwhile, projects are emerging that suggest compelling, transformative possibilities for comic book creators, fans, and scholars to collaboratively speak back to comic book culture. A project like My So-Called Secret Identity, initiated by media scholar Will Brooker out of a desire to "build a better Batgirl," models a collaborative approach to transformative criticism that foregrounds the work of female artists and collaborators to comment on, and creatively correct, some of the more problematic tropes that tend to weigh down superheroine comics. Brooker's 2001 book Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon, opened with an admission and embrace of his long-standing affective ties to the property and reflected on his own fannish textual production. Likewise, the article that inspired My So-Called Secret Identity, a history of the Barbara Gordon iteration of Batgirl, models precisely the sort of scholarly impulse Bukatman suggests might be most fruitful for emerging comics studies. As Brooker's project and the growing array of female-driven comics criticism makes clear, fannish frustration can be also be a perfect starting point to begin an analysis. Fascination will unquestionably drive the future waves of comics scholarship, but frustration might facilitate more praxis-oriented, transformative approaches to this work.

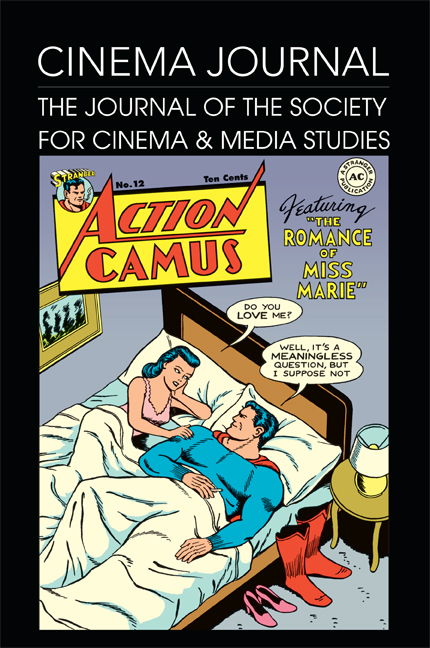

[6.6] The stakes are ultimately higher than building a better Batgirl; they're about building a better comic book culture, one that acknowledges and holds itself accountable to its diverse and passionate readership. Fittingly, the cover image that accompanied Cinema Journal's first major foray into comic studies was taken from R. Sikoryak's "Masterpiece Comics" series, which fannishly mashes up iconic comic characters with canonical literary works and authors (figure 8). Sikoryak's "Action Camus" offers an absurdist spin on Action Comics' Superman, but it also neatly (and perhaps unwittingly) encapsulates the gendered tensions currently underpinning comic book culture. One of the dangers of visibility politics, a by-product of its either/or logic, is that it has the potential to reproduce the very structures of dominance and exclusion that it seeks to dismantle. I am not advocating for comic book scholars or the comics industry to exclusively focus their energies on female readers at the expense of misrepresenting or alienating comics' core demographic. Reading "Action Camus" as a satire of the comic book industry's historically genre-essentialist efforts to appeal to female readers and a commentary on superhero comics' estranged relationship with female fans, 2011 and 2012 have witnessed female comic fans grappling with their containment as Miss Maries within comic book fandom. We don't need to be told that we're loved, but we would like to be assured that we aren't meaningless.

Figure 8. The cover of Cinema Journal 50 (3), featuring a piece from R. Sikoryak's Masterpiece Comics, unwittingly reflects on comic book culture's rejection of female fans. [View larger image.]