1. Amazing beginnings, ultimate innovation

[1.1] After 60 years of ongoing publication, Marvel Comics thought its superhero line was aging and wasn't attractive to new readers. In 2001, they created a line of comics, Ultimate Universe, so that new fans could begin reading the line without the pressure of knowing the backstory. Ten years into the Ultimate line, in August 2011, this universe also became prohibitively difficult for new readers to enter. In a bold choice, Marvel Comics killed Peter Parker, the secret identity of Spider-Man, and introduced a new character to carry his mantle: Miles Morales, a half-Latino, half–African American teen. This new representation of an established character represented a victory for some fans, who thought that superheroes, who were mainly white, did not truly represent all people. But the very mention of such a change upset other fans, who thought that Spider-Man was already representative of a particular population. As Dave Itzkoff wrote in a 2011 New York Times article, "Though both Marvel and DC Comics, its chief rival, have featured black and minority superheroes over the years, [series writer] Mr. Bendis said that changing the identity of Spider-Man, a central character in the Marvel mythology, if not its single most recognizable property, was a watershed moment."

[1.2] This watershed moment, encompassing both the origin of the new character and the initial fan reaction, links comic book culture and the media to interrogate notions of race and its meaningfulness to the fan community. Although both Spider-Men have origin stories that involve the bite of a radioactive, genetically altered spider, the black Spider-Man has his own origins in a Twitter campaign (http://www.twitter.com). In this online conversation, the change of Peter Parker to Miles Morales was precipitated by fans who wanted comedian and television star Donald Glover to play the web slinger in the upcoming reboot of the film franchise. Ultimately, Glover did not win the role, but the campaign caught the attention of the current Spider-Man editors and writers. To them, Spider-Man and the Ultimate Universe needed a boost, and a multiracial characterization was the perfect way to do just that.

2. Morales's origin story

[2.1] Technology and lifestyle Web site io9 (http://io9.com) deserves credit for starting the discussion about Spider-Man's race. Marc Bernardin, in a 2010 post, "The Last Thing Spider-Man Should Be Is Another White Guy," argued that Spider-Man is not defined intrinsically by his race but by his identity as a New Yorker and by his understanding of choice, as represented by the often-quoted line, "With great power comes great responsibility." Spider-Man's whiteness is thus not defining but merely accidental. As Bernardin wrote, "Lee and Ditko created a wonderfully strong character, one full of complexity and depth, who happens to be white. In no way is Peter Parker defined by his whiteness in the same way that too many black characters are defined by their blackness." Bernardin thus suggests that the same stories can be told irrespective of the race of the man wearing the mask; he advocated a color-blind approach to the character.

[2.2] Two days later, on May 30, 2010, actor Donald Glover posted on his Twitter feed (https://twitter.com/MrDonaldGlover, now moved to https://twitter.com/DonaldGlover) a retweet: "@io9 wrote a post about casting a non-white #spiderman for the reboot. Some suggested @MrDonaldGlover. I agree with this." Glover posted two tweets directly after, using the #donald4spiderman hashtag: "You guys. Let's make this happen. #Donald4spiderman" and "Sweet. You guys are awesome! Retweet. Someone start a facebook page. I'm going to start doing shit. #donald4spiderman." Glover, best known for his role as nerdy jock Troy on NBC's comedy Community (2009–present), a TV show about a group of friends at community college, had a fan base that loved the idea of Glover as Spider-Man. They created and posted dozens of Photoshop mock-ups of the actor in Spider-Man comics and with his face on Spider-Man's body in shots from the previous films. Glover, a couple of days into the campaign, clarified in a tweet, "Some people are mistaken. I don't want to be given the role. I want to be able to audition. I truly love Spider-Man. #donald4spiderman."

[2.3] The #donald4spiderman campaign became a top 10 trending Twitter topic that Memorial Day weekend and was reported in the New York Magazine, the Washington Post, and on several other Web sites such as MTV.com (http://www.mtv.com/). Stan Lee, cocreator of Spider-Man, said of Glover's campaign, "Here's the point: We've already had the Kingpin in 'Daredevil' portrayed by a black man, where he was white in the comics, [and] we've had Nick Fury portrayed by a black man where he was white in the comics…But not that many people had seen these characters—not that many moviegoers are familiar with them" (Marshall 2010). Changing the race of these characters mattered less because they were not household names in the same way that Spider-Man was. Lee continued, "Everybody seems to be familiar with Spider-Man, so I say that it isn't that it's a racial issue—it's just that it might be confusing to people…But that's a matter for the people at Marvel to take into consideration" (Marshall 2010). Lee explicitly stated that he was not advocating a particular view, but that Glover should have a chance to audition for the role. Academics weighed in too: Phillip Cunningham (2012), in an essay about "Donald Glover for Spider-Man," pointed to other creators and fans who addressed the universality of Spider-Man and who saw no reason why the character could not be black, Latino, or something other.

[2.4] Ultimately, the campaign failed to secure Glover the role, which went to Andrew Garfield instead. Although the fans may have felt that they lost this battle, it was not the end of Glover's Spider-Man. The second season premiere of Community, "Anthroplogy 101," which aired on September 23, 2010, opened with Glover in Spider-Man pajamas (figure 1). Show creator Dan Harmon explained the presence of the pajamas in the opening sequence by noting that Troy, Glover's character in Community, "would definitely be a Spider-Man fan…And it's definitely a cutesy inside wink at the Donald Glover for Spider-Man campaign" (Adalian 2010).

Figure 1. Glover in costume. Screen shot from September 23, 2010, NBC TV program Community, season 2 premiere, "Anthroplogy 101." [View larger image.]

[2.5] Before the movie announcement, Marvel Comics publicized the killing of the comic book version of Peter Parker as "The Death of Spider-Man" (figure 2). Marvel intentionally played coy with their plans in this ad, leading to speculation that Marvel might kill the character published since the 1960s. Instead, they killed the Peter Parker in the parallel Ultimate Universe created in 2001.

Figure 2. Death of Spider-Man ad copy. [View larger image.]

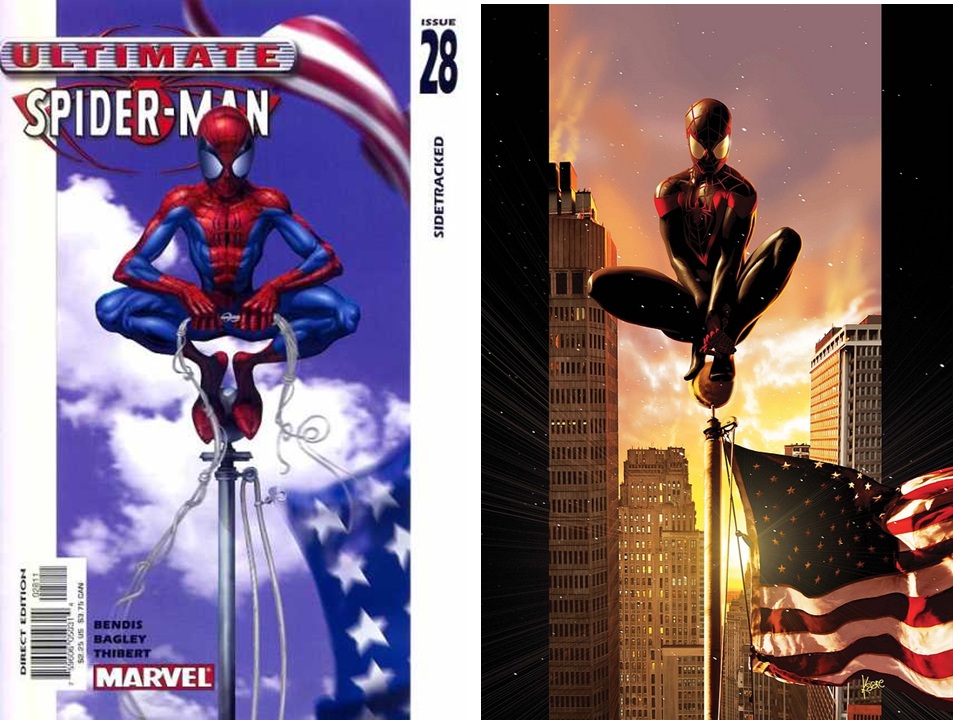

[2.6] Marvel chose to change Spider-Man's identity to someone other than Peter Parker as a first step in a publicity blitz to call attention to the line of comics. Series writer Brian Michael Bendis stated that Marvel needed to change the secret identity to someone other than Parker because introducing a second Spider-Man alongside the first would only force the two into competition. For Bendis, seeing Glover wearing Spider-Man pajamas in the Community episode cinched the deal to change the character: "I would like him to be Spider-Man. Very Much" (Chang 2011). However, Bendis acknowledged that there were differences between Miles Morales and Glover, including age and voice. From the writer's view, altering the character's race made the change all the more provocative. The comic could have a fresh outlook, but without forgetting its roots. The new character uses some of the same jokes as Peter Parker and is often drawn in poses that echo those of the iconic white Spider-Man (figure 3).

Figure 3. Two Spider-Man covers demonstrating parallelism in the representation of Peter Parker and Miles Morales. [View larger image.]

3. Not everyone is a fan

[3.1] Marvel Comics, by changing Spider-Man's race, roused Internet fans concerned with that topic. After the Community episode where Glover wore the Spider-Man pajamas, series creator Dan Harmon noted that he was struck by the "curious eruption of a previously unknown demographic of racist comic-book readers it ended up uncovering" (Adalian 2010), referring to the negative Internet backlash against the possibility of changing Spider-Man's race—a backlash also noted by Glover. Some Spider-Man fans on the Internet ignited a firestorm of racism. For example, on August 1, 2011, two days before the release of the first appearance of the new Ultimate Spider-Man, a comic book retailer tweeted two comments: "Q: Ben dat you? A: How you know? A: Dem lips nigga, no mask gonna hide dem," and "Q: Hey Spidey, why you web slinging so fast? A: KFC closing in a few minutes." These Twitter comments appeared on the comic book industry rumor Web site Bleeding Cool (http://www.bleedingcool.com/). By posting these racist comments, the retailer acted against his own interests—selling comic books. The retailer later clarified his comments: "Marvel making Ultimate Spider-Man African American is simply a cheap publicity play to bolster sinking sales. I think it's a desperation move, and I took some good natured jabs at it" (Constant 2011, emphasis in original).

4. Conclusion

[4.1] The fans proved their power, and the power of new media, through the Spider-Man campaign. A simple Internet post asking a question about Spider-Man's race in a film turned into an Internet campaign about an actor that led fans to interact with each other as well as with the actor, which in turn led to the attention of media producers, which resulted in a change in Spider-Man's race in a print comic book (Truitt 2011a, 2011b). White Peter Parker was transformed into multiracial Miles Morales, hero and ambassador of the diversity of 21st-century America.

[4.2] As a character, Morales speaks to a different audience and can say different things than Parker can. Morales, as evidenced by the backlash against the change as well as the voices in favor of it, energized an audience and renewed interest in the Ultimate Universe version of the character. For Marvel, this may have simply been all about publicity; however, the change does make a difference. Spider-Man has universal appeal, but the race of his secret identity changes the dynamic of the character, leading to new modes of representation and fan consumption.

5. Acknowledgments

[5.1] I thank Dr. Germaine Halegoua (University of Kansas), Dr. Nancy Baym (University of Kansas), Phillip Cunningham, Elizabeth Potter, and John Bond.