1. Problematizing comics fandom: A multitude of textual universes

[1.1] The relationship between slash fan fiction and comics fandom is problematic not only because of the shift of medium from source text to fan text but also because of the shift of fan community. Comics fandom is often viewed as consisting of heterosexual white men and comics are often explicitly marketed to them, excluding and othering the rest of the audience. Comics fandom online subverts this expectation of audience because the majority of fan authors and creators are women. While canon plots privilege action and conflict, and the problematic depiction of women characters in them is so obvious it hardly need be discussed, comics fan fiction reverses these trends: stories privilege emotional arcs, and female characters are depicted as more recognizably human even when they are secondary to the male characters.

[1.2] Comics fan works thus become completely transformative because of the shift in both fan space and fan audience: texts that are homophobic become homophiliac, authors and readers who are male become female, and that which had previously been other becomes the new norm. For these reasons, the fans are not just aware but indeed hyperaware of their own identity as subaltern and subversive practitioners.

[1.3] When the overwhelming presentations appear homophobic, where are the positive queer identities to be found in these works? That homophobia is used throughout these texts (and others within the comics genre) by the authors to establish queer identities has been made readily apparent. All too often these identities are crafted as a reaction to the homosexual's interruption of society's heteronormative homosocial. As a result, these homophobic identities regularly appear as threats to heterosexual society: gays as murderers, villains, rapists, and pedophiles. And yet we have also seen where the positive identities can exist. It is due to the very nature of comics' physical attributes (their visual aspects, panel structures, and blank gutters) that we are allowed an alternative space where queer identities that are not saddled with homophobia can be formed. (Buso 2010, 79–80)

[1.4] Through this lens, all of comics slash fandom becomes a resistant and even a queer reading, an insistence on enacting and creating a virtual safe space for fans. Further, this self-awareness of identity (as feminine, as queer) becomes explicitly politicized through its declaration of being, which is then often rewritten from within the fan texts themselves. Comics fandom and fan fiction in particular face an especially unusual challenge because of the difference of medium. While many comics fan works are themselves comics—some of which are of professional quality in both artwork and writing—many more are in the traditional fan fiction format of short stories or novels. In some ways, this format is at odds with the original medium, in which the interplay of illustration, textual narrative, and dialogue is as crucial to the form as the story itself. For instance, Scott McCloud explains what he calls closure by describing how the comics format invites the reader to acknowledge that comics (and thus, all texts) are artificial creations that our brains then rationalize to fill in the blanks:

[1.5] See that space between the panels? That's what comics aficionados have named "the gutter." And despite its unceremonious title, the gutter plays host to much of the magic and mystery that are at the very heart of comics. Here in the limbo of the gutter, human imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea. Nothing is seen between the two panels, but experience tells you something must be there. Comics panels fracture both time and space, offering a jagged, staccato rhythm of unconnected moments. But closure allows us to connect these moments and mentally construct a continuous, unified reality. (1993, 67)

[1.6] Fan fiction and other fan works are efforts to join these disconnected moments and make sense of them in another fashion, by piecing together those elements visually present in the text with those that are clearly not. Reconstructing these pieces to create new works is not only a part of reading comics textually but also a part of reading fan works.

[1.7] Marvel's Avengers multiverse is a troublesome text because of its historical grounding and constant revision. The emergence of movieverse fandom creates a tabula rasa for some fans, a blank slate on which they can write a new text by creating new origins and points of reference that do not require previous knowledge. Rather than only supplying missing scenes or explications and expansions of canonical material, they can select and connect elements as they please from the comics, films, and cartoons, making choices about characterization, time line, history, and so on, and create their own unique universe in which to tell the story they want to tell. Such a story might be an alternate universe (AU) story in more traditional fandoms. However, thanks to the complexity of Marvel's own multiverse, Avengers canon already contains AUs from which fans can, again, select or rewrite elements. Thus Avengers fandom creates not only a separate space for fans but also infinite possibilities for fandom. Movieverse fandom can itself be viewed as a kind of AU or reboot, because the feature films provide origin stories for the heroes that sometimes differ significantly from the various versions offered in the comics. In the film Thor (dir. Kenneth Branagh, 2011), the eponymous character is an alien (Asgardian) deity throughout the story, with no second identity as mortal doctor Donald Blake (aside from a brief comedic reference). Likewise, in Captain America: The First Avenger (dir. Joe Johnston, 2011), Steve Rogers and Bucky Barnes are shown as men of the same age with a long-standing friendship, rather than an older hero with a teenage sidekick. The films are self-contained and do not require knowledge of previous canon, which makes them accessible to new fans.

[1.8] That said, Avengers movieverse fandom predated the release of the actual film The Avengers (dir. Joss Whedon) in 2012. Many stories appeared in 2011, looking forward to the anticipated events of the film, and writing them thus required some knowledge of canon comics. Additionally, Avengers movieverse fandom relies not only on this textual knowledge but also on extratextual materials, such as promotional images and the other iterations of the franchise, to contextualize its stories. This is where the self-awareness of fandom—identified through fans' conscious decisions to preserve their texts as historical documents—again comes into play, because shared knowledge is key to maintaining fandom and documenting fannish history. Numerous shared documents online, such as elspethdixon's Steve Rogers/Tony Stark Ship Manifesto (2008) and muccamukk's Captain America/Iron Man Slashy Moments List (2010–12), provide fans with the knowledge needed to maintain the ship's visibility. In other words, the presence of the ship in numerous branches of preexisting fandom makes a case for its adoption into movieverse fandom as well. This adoption sets up a series of expectations within movieverse fandom: How do the characters meet; how do they fall in love; how do they function together? Even before the 2012 release of The Avengers, the movieverse already played on viewer expectations by subverting the traditional heroes' origin stories: Iron Man is more antihero than hero, particularly in Iron Man 2 (dir. Jon Favreau, 2010) when he mocks Congress as a witness during congressional hearings, uses his armor for (self-)destructive purposes during a drunken binge, and in general is treated as more of a problem celeb than an icon. Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) wears all the tropes of a conventional war story on its sleeve far more than it does those of the superhero genre.

[1.9] In the slash genre, however, this playing on expectations can present new problems for the reader. Traditional slash narratives have often posed an issue for readers in that they essentially reproduce aspects of the traditional romance with the notable difference that the protagonists are, of course, two men. It has only been in the last decade that fan writers have become more willing to label the characters of these stories gay, or at least bisexual; especially in the 1970s and 1980s, fans wanted to distance beloved characters from the stereotypes and even the identity of gayness (note 1). Instead, they depicted the men as sharing a great, transcendent love that eliminated the boundaries of gender. Indeed, it was an article of faith that neither man would have had same-sex sex prior to their romantic involvement with each other—unless, of course, one of them had previously been prostituted or raped, in which case the sexual consummation became a sexual healing. This specific genre of hurt/comfort fiction earned the notable appellation "magic cock stories," of which much more could be said, perhaps, but not in this essay.

[1.10] Many scholars have attempted to explain why women read and write slash stories. For the purposes of this study, I'm not interested in recapitulating this research, since it has been so heavily documented elsewhere, but I would like to note the work of Joanna Russ on the topic. "If you ask 'Why two males?'" she said, "I think the answer is that of eighteenth-century grammarians to questions about the masculine-preferred pronoun: 'Because it is more noble.'…No one [can] imagine a man and woman having the same multiplex, worthy, androgynous relationship, or the same completely intimate commitment" (1985, 84).

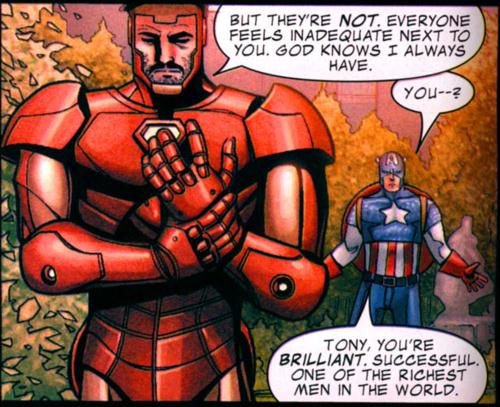

[1.11] As frustrating as it seems some 30 years later, this attitude definitely persists. Further, the most specific element—(gender) equality—actually grounds the Captain America/Iron Man or the Steve/Tony ship. As written by fans of that ship, their relationship is the only possible true partnership (figure 1).

[1.12] Steve is an idealist with a practical streak, while Tony is an "ends justify the means" pragmatist with an idealistic streak. This leads to frequent clashes between the two of them over methods and tactics, but at [sic] also means that the two of them balance one another remarkably well. Tony challenges Steve, forces him to rethink his assumptions and defend his ethical position—and Steve needs that. Without someone to question him, to treat him as a friend and comrade instead of "Captain America: Living Legend," he'd still be stuck in 1945. For Tony, Steve's friendship and faith in him provides both a sanity check that keeps him from straying too far into supervillain territory, and the support that allows Tony to keep on fighting the good fight, to keep on trying to live up to and be worthy of that faith. Tony has declared on multiple occasions that he thinks Steve is a better man than he is (he even goes so far as to tell Steve that he's perfect), and that Steve's faith in him is the one thing that allows him to still have faith in himself. (elspethdixon 2008)

Figure 1. Subtext? What subtext? Steve and Tony discuss their feelings (and emotional vulnerability) in a panel from Captain America/Iron Man: Casualties of War (2006). [View larger image.]

[1.13] The self-awareness of fandom transforms within the Steve/Tony ship into fiction that verges on nonfictional commentary, or meta, rather than story. The romance as realized by the fans translates into Steve and Tony becoming aware of and analyzing their own feelings at length. A popular trope within the fandom is that of identification and explication; the goal of the story is for the characters to come to terms not only with being in a same-sex relationship but also with why the specific relationship works for them.

[1.14] Rogers didn't look surprised or curious at all. Just frustrated. "Let me guess," he said sharply. "What on Earth could a nice guy like me see in—Tony." Lindsay could actually hear the adjectives Rogers had cut out of the sentence. "Do you know how many people just walk up to me on the street every day and ask me that?" Rogers demanded. "And now it's apparently such a tantalizing mystery," he said the word like an insult, "that you're willing to risk your life over it? What is wrong with you?"

"Steve—" Tony began, his tone apologetic.

Rogers spun to face Stark instead of Lindsay. "No!" he snapped. "This is not your fault. And it's not a 'reasonable level of media interest' either." The quote in the words was clear. "When did reporters lose all respect for privacy and decorum? And why is it so unbelievable that I'd fall in love with a dedicated and brilliant man with whom I've shared some of the most significant moments of my life?" (Nix 2012; emphasis added)

[1.15] This trope not only allows for character studies but also offers fans a route to conversion to the ship. A reader who is curious about the pairing may be more convinced by, and become more invested in, the ship by a fictionalized account of how the romance works than by a detailed nonfiction analysis like the Ship Manifesto.

[1.16] Anne Kustritz reiterates this idea in her essay "Slashing the Romance Narrative," in which she says,

[1.17] Slashers often exaggerate the extent to which slash characters seem drawn to talk about the power dynamics within their relationship, demonstrated in a series of stories that parodied the characters' tendency to begin philosophical discussions about their relationship during sex…Authors meticulously create an equality relationship dynamic in which characters are completely equal in everything from decision making to love making, and from patterns of dress to household chores to levels of attractiveness and financial security. (2003, 377)

[1.18] However, this dynamic is rewritten by Steve/Tony fandom in that, in Steve's and Tony's private lives at least, there is a fundamental difference in wealth. Steve came of age in the New York of the 1930s, with its soup kitchens and breadlines. In some comic and film time lines, he has also spent time in an orphanage or boys' home after his mother died of TB, and has been an art student struggling with tuition bills. He has always had to work to make ends meet, and often meager ends at that. In contrast, Tony Stark has always been a wealthy, privileged profligate. Essentially, despite their equality as male superheroes, their material disparity returns their relationship to something closer to the traditional romance, with Tony as the wealthy, experienced suitor and Steve the innocent ingenue.

[1.19] In some ways, fandom anticipated this element of class and economic tension prior to the 2012 film. In that film, Steve and Tony have multiple verbal confrontations stemming from their different backgrounds:

[1.20] Tony Stark: Following is not really my style.

Steve Rogers: And you're all about style, aren't you?

Tony Stark: Of the people in this room, which one is (a) wearing a spangly outfit, and (b) not of use?

…

Steve Rogers: Yeah, big man in a suit of armor. Take that off, what are you?

Tony Stark: Genius, billionaire, playboy, philanthropist.

Steve Rogers: I know guys with none of that worth ten of you. I've seen the footage. The only thing you really fight for is yourself. You're not the guy to make the sacrifice play, to lay down on a wire and let the other guy crawl over you.

Tony Stark: I think I would just cut the wire.

Steve Rogers: Always a way out. You know, you may not be a threat, but you better stop pretending to be a hero.

Tony Stark: A hero, like you? You're a laboratory experiment, Rogers. Everything special about you came out of a bottle. (Whedon 2012)

[1.21] These scenes echo many that had already appeared in fan stories, in which Steve and Tony are unable to get along because of their clashing personalities. In "Ready, Fire, Aim" by gyzym, they aren't even able to apologize to one another without getting into another fight:

[1.22] "You came all the way out here to apologize?" Tony says. "Have they not taught you to use the phone, like normal people?"

"I'm not apologizing!" Steve snaps, and then visibly reigns [sic] himself in. "No, you know what, I am apologizing. I'm sorry. I'm just…not adjusting all that well, I guess, and then there's you, and you look a lot like—"

"Get out of my house," Tony says, instinctive, automatic, before he can finish that comparison.

Steve jerks back, stunned, and then narrows his eyes. "Excuse me?"

"You heard me," Tony says. "Look, Rogers, you want teammates or whatever, fine, great, you've got a whole gaggle of S.H.I.E.L.D. cronies waiting to bust out their guitars and sing Kumbaya with you, have fun, but I told you, I don't play well with others, okay? So you and your…apology or whatever, you can just go, I don't need you to do me any fucking favors."

Steve stares at him with his mouth open for a long minute. Then he says, "What're you—no, you know what, I don't care. Fine. If that's the way you want this to be, that's just fine with me. Have a lovely evening, Mr. Stark."

"Fine!" says Tony. "Good! Great! I will!" (gyzym 2011)

[1.23] In fan fiction, their tension is interpreted as having undercurrents of sexual attraction, of which the characters may or may not be aware. Onscreen in the 2012 movie, Steve and Tony's interactions were read by many as having this same motivation, especially in the climax of the film, in which Tony is feared dead. Surrounded by his teammates, he jerks back to consciousness after the Hulk roars loudly. He gives a short cry and looks around in panic, saying, "Please tell me no one kissed me?" Steve looks away, relieved and blushing. It is up to the invested viewer to guess at the source of Steve's embarrassment.

[1.24] As can be seen, elements in both fiction and film are open to multiple readings. Steve/Tony fandom is remarkably aware of the many ways in which texts can be read and interpreted, and it actively documents its history through numerous archives. In larger, more well-known fandoms, it is not unusual for Web resources to be abandoned or orphaned (or even deleted altogether) once the fan who maintains them has left the fandom. In Steve/Tony fandom, these resources are often adopted by other fans so that they are continually maintained for new fans or those who want access to older materials. Many of the fandom's works have been duplicated on LiveJournal, Dreamwidth, and the Archive of Our Own to prevent textual loss through technical failures, people dropping out of fandoms, or other means. Resources such as the Captain America/Iron Man Slashy Moments List have had a series of moderators or curators who have kept the page up to date over a period of years.

[1.25] Further, the variety of fandoms within both the ship and the official franchise is astonishing. As mentioned above, Marvel has a multitude of iterations of the Avengers, Captain America, and Iron Man available, including not just the comics (which themselves have a dizzying array of versions) but also the cartoons and films. Fan authors and communities normally specify the universe referenced in a fan work, both to alert readers to version-dependent elements of characterization and history and to allow them to avoid spoilers. For instance, comics fans will recognize the significance of Agent 13 and the Winter Soldier, while movie fans may not. With the announcement that the forthcoming film Captain America 2 would be subtitled The Winter Soldier, several debates were struck up online. What, if anything, do comics fans owe to movie fans to ensure that the latter remain unspoiled if they so desire? Do plot points that are years—and sometimes decades—old really count as spoilers? It remains to be seen how these questions may be resolved. As the following discussion will show, characterization and plot can diverge significantly enough that their interpretation by and through fan works should prove problematic—and yet it doesn't, because of fans' commitment to unifying universes.

2. The use of the alternate universe

[2.1] Marvel Comics canon is essentially already a shared universe, particularly when it comes to massive story lines that cross over multiple comics titles and have far-reaching consequences, such as House of M and Marvel: Civil War. (This latter story, which involved more than a hundred issues of fifteen monthly titles, pitted Captain America and Iron Man against each other in a conflict over a law requiring superheroes to register with, and essentially become weapons of, the US government. In an epilogue titled Civil War: The Confession, a distraught Iron Man admitted that nothing he did during the conflict was worth the loss of everything that mattered to him, namely Steve.) Characters stepping in and out of each others' monthly titles or sharing adventures in special miniseries are all but de rigueur. Moreover, stories are told in a multitude of time lines or universes (a multiverse), in which events are freely rewritten or replayed. Marvel maintains an online list of these universes (http://marvel.wikia.com/Multiverse), and tsukinofaerii (2012) has compiled a useful fannish aide-mémoire as well. Four are of particular interest to Steve/Tony fandom.

[2.2] The 616 universe is the standard, mainline continuity, beginning with the 1941 Captain America comics and continuing through subsequent titles from the 1960s through to the present. Because of its longevity, the time line of events has been blurred, so that while nearly five decades' worth of stories have occurred since the 1960s iteration, they are compressed into the lifetimes of characters who remain in their physical prime and virtually ageless.

[2.3] The 1610 or Ultimates universe reboots the events of 616 while simultaneously displaying darker themes in story and representation. For several reasons, it's widely suspected among fans that Marvel created this universe to enable the production of feature films; among other things, the character of Nick Fury was redesigned as a near double of Samuel L. Jackson.

[2.4] The movieverse or MCU (Marvel Cinematic Universe), also called 199999, encompasses all the major film interpretations from 2008 onward, including projected sequels to Thor and Captain America and rumored stand-alone films for other characters.

[2.5] The 80920 universe, depicted in the animated series The Avengers: Earth's Mightiest Heroes (2010–2012), shares details with both 616 and the movieverse that other universes do not, such as physical appearance (Tony's brown eyes, always depicted as blue before Robert Downey Jr.'s appearance in the films) and JARVIS the AI rather than Jarvis the butler.

[2.6] Some details of canon are shared from universe to universe. Tsukinofaerii notes that The Avengers: Earth's Mightiest Heroes combines the basic plotlines of 616 with elements of 199999, such as JARVIS being an artificial intelligence and Tony having brown eyes (like actor Robert Downey Jr.), rather than blue as in the original comics. The 1610 Ultimates line, initially published in 2002, also set the stage for the series of films by retconning many events and characterizations, emphasizing streamlined story arcs that require no knowledge of previous history and focus on an ensemble rather than a single point of view.

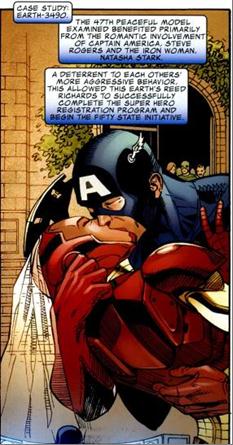

[2.7] In addition to these universes, many more appear as one-shots or are referenced only briefly. For example, universe 3490 is seen only in a single panel in an issue of Fantastic Four: Dark Reign #2 (figure 2). In this universe, Iron Man is Iron Woman while Captain America remains male; the single image we have of them together is their wedding kiss. The narrative tells us that their romance acts as a "deterrent to each other's more aggressive behavior" and thus circumvents the Marvel Civil War (http://marvel.wikia.com/Natasha_Stark_(Earth-3490)). The whole tragedy of the Marvel Civil War is that, although Steve and Tony talk to each another, they are unable to come to a compromise and instead continually rage at each another as the country falls to pieces around them. Their relationships are virtual analogs of the bodies politic: one couple can function peacefully by (presumably) discussing their feelings, thus leading to peaceful unification, while the other cannot.

Figure 2. The marriage of Captain America and Iron Woman. From Fantastic Four: Dark Reign #2.

[2.8] Sheenagh Pugh notes that "the one aspect of canon that is not usually up for alteration is the nature of the characters" (2005, 65). Both tsukinofaerii and elspethdixon demonstrate through their extensive notes and analyses that the combination of character traits and histories that make up Tony Stark/Iron Man and Steve Rogers/Captain America are often those same elements that promote the pairing, such as their repeated statements that each means the world to the other and their flowery interior monologues ("Captain America, Steve, I look at your handsome face…into your clear azure eyes…") (note 2). Within the 1610 universe, however, the darker themes and character traits emphasize their heterosexuality. These comics emphasize the sexuality and violence of superheroics, including scenes of Tony in bed with Natasha (typically his sexual encounters are alluded to but never seen) before she murders Jarvis, and Steve viciously beating Hank Pym after Janet is hospitalized. Hence canonical 1610 Steve/Tony fan stories are rather short on the ground, though there are some 1610 AUs of note.

[2.9] As is often the case in new and quickly growing fandoms, the AU modern-day trope (in which science fiction characters are rewritten as normal, workaday people) has seen burgeoning use. This trope is popular because it is accessible to new fans. Most AUs presuppose new backgrounds for the characters that may be based on decades of preexisting history or commentary. A specifically modern-day AU, on the other hand, has no presuppositions to build upon: instead, the featured characters exist in a world of the fan author's own creation, generally with the same emotional relationships as their originals (friends, lovers, colleagues) but in a different environment. Steve/Tony modern-day AUs frequently keep elements such as Stark's wealth and Rogers's transformation but reconfigure them to be more realistic: Tony is a programming genius who makes software and apps rather than AIs or flying armor; Steve's evolution from skinny asthmatic to buff Adonis is due to an intense health and workout regimen.

[2.10] Modern-day AUs give the characters a tremendous variety of new professions, but certain tropes recur over and over again across multiple fandoms. In almost every fandom, for instance, there is the coffee shop AU, in which one character is a barista and the love interest is a repeat patron. Fan author sol-nox puts this genre to use for Steve/Tony in a story called "Caffeine, Otherwise Known as the Key to Tony Stark's Heart":

[2.11] Tony returns the following morning and Steve looks astonished. Tony can't imagine why. He'd said he was going to come back, hadn't he?

When Tony first heard that a coffee shop was going to be opening across the street from Stark Tower he had been interested in a detached sort of way. A potential supplier for his caffeine-fueled nights in the workshop? Sure, he was all over that. And then Tony had caught a glimpse of its owner.

Tony can't pinpoint the exact reason why he's taken an interest in the young art-student-gone-barista. Actually, no, that's a lie. He can. Steve is fucking hot. Tall, built like a comic book superhero. He had those amazing blue eyes and that pouty mouth. Plus he had an air of sweetness and innocence that Tony, being Tony, had a base urge to corrupt.

Tony steps up to the counter and presents his best smile. Steve's eyes dance shyly away. That was much cuter than it had a right to be. (sol-nox 2012)

[2.12] Businessman Tony as a patron ordering coffee from barista Steve is the story's "meet cute." Other characters from the comics and movies appear in small roles: Nick Fury is Steve's assistant, and Bucky is mentioned as Steve's childhood friend recently fallen in Afghanistan. The story largely plays out as a series of encounters in the coffee shop, detailing the making and serving of beverages as a kind of language of romance.

[2.13] Readers and writers like coffee shop AUs partly because coffee shops are a comforting environment (and also, probably, where many authors actually write their fics). As in fairy tales, the elements common to such stories—the flirty barista who offers special concoctions, the recurrent visits to a place that offers something like sanctuary, the happy ending—instill expectations that are then pleasantly met. Indeed, the popularity of this trope has prompted some complaint.

[2.14] Another near-universal trope is the high school AU, in which the main characters are all high school students. (There are also college AUs, though high school AUs are more numerous.) Part of the reason for this is likely that high school stories are themselves a recurring trope within popular mass culture, and since many fan writers are in their 20s or 30s, high school is a recent experience for them, one that can be referred to knowledgably and without research. In high school AUs, the focus becomes the traditional dialectic of the nerd and the jock—and in Steve/Tony fics, either may play either role. Tony is often portrayed as being superficially popular but still socially ostracized for his youthful genius; Steve can be portrayed as a skinny art nerd or as a bulky football player. Fan author settiai chose to interweave these possibilities in "High School Is Not a Musical." In her story, Tony is a young inventor with a propensity for pyrotechnics and Steve straddles expectations as both a would-be illustrator and an athlete. As in many other stories, the boys awkwardly miscommunicate:

[2.15] Steve folded his arms over his chest uncomfortably. "Uh, don't take this the wrong way, but why are you even talking to me?"

Tony blinked, apparently in surprise. A slightly hurt look appeared on his face, and he opened his mouth. Whatever he was going to say, however, was cut short by a firm hand coming down to rest on his shoulder. (settiai 2010)

[2.16] As in other stories, their developing friendship eventually leads to deeper feelings. College AUs are often longer, with slowly building, better-developed narratives. In these, the characters are most often college students, though sometimes they are professors instead. This genre is less common, most likely because college studies are more specialized; it's harder for characters to be rewritten within a specific discipline than it is for them to represent well-known high school archetypes. For instance, in Steve/Tony college AUs, Steve is usually an art student while Tony is usually in computer science or engineering. Like high school AUs, they reiterate certain stereotypical elements of American school experience, such as the partying student (Tony) and the conscientious student (Steve):

[2.17] "So, how did I end up with you?" Tony asks, because he honestly has no idea. He remembers vaguely meeting his anti-Pepper and then there was more drinking and a sudden urge to go to the library. He's not really sure what was so pressing.

Steve was looking amused but his face freezes, goes carefully blank and he says, "You were drunk I guess."

Tony wants to ask Steve if he did anything. He feels like he should apologize but then again, with Pepper around, he constantly feels that way. "Sorry if I said anything…weird?"

"S'fine," Steve dismisses, not elaborating. "You want me to walk you back to your room so it doesn't look like you're doing a walk of shame?" Steve asks, back to amused and Tony just grins at him, enjoying this soft, morning version of Steve more than he'd like to admit. (kellifer_fic 2011)

[2.18] This story, "If at First" by kellifer_fic, goes on to describe the characters spending late nights in diners drinking cheap coffee, falling asleep in the library, and struggling to get to class on time after oversleeping. In short, these interpretations of AUs privilege a form of normalcy over the superheroics displayed elsewhere. Other stories, however, return to the heroic form for a different purpose: social justice.

3. "Some time-displaced war heroes marry genius billionaire playboy philanthropists, get over it"

[3.1] An AU, whether in canon or fanon, can acknowledge the nonstereotypical comics audience—that is, women and LGBT readers. Fandom traditionally creates a safe space for many people who, for whatever reasons, lack it in their nonfannish lives. In comics canon proper, the multiplicity of AUs allows the characters to step outside their own safe spaces, offering stories in which Tony Stark hasn't always been a wealthy multimillionaire or Steve Rogers hasn't always been a hero. These "what ifs" open a world of possibilities for character exploration that nonetheless return them both to the people we know, as well as carving out a new space they can inhabit.

[3.2] The lengthy history of the Avengers, and particularly of Captain America, allows both the corporate authors and the fan authors to infuse political meaning into the characters, as is demonstrated through the entirety of Marvel: Civil War. All the narrative tension and meaning of this story comes from the struggle and failure of Iron Man and Captain America to find a common ground. Steve/Tony fandom largely developed after the publication of Marvel: Civil War in 2006–7, at the same time that same-sex relationships were being more often discussed in popular culture. Safe spaces for LGBT people are increasingly seen as desirable both within and outside fandom. The It Gets Better movement, for instance, is aimed at preventing LGBT teen suicide. Steve/Tony stories, by necessity, involve Steve coming to grips with his sexual identity as he comes to terms with 21st-century morals and mores. Numerous stories do this by showing Steve trying to balance his duty as Captain America and advocating for the civil rights of others. In hetrez's story "Average Avengers Local Chapter 7 of New York City," all of the Avengers, and especially Captain America, inspire a grassroots campaign of public service and social change that reaches its emotional climax and plot apotheosis when Steve comes out during an interview on The Colbert Report:

[3.3] "Yesterday, a boy killed himself. He loved other boys, and he was bullied for it, and he took his own life. When I learned about him, I thought, this is something I can do. I can tell people who I am, that I'm a hero and I love men and it's not wrong. I can make them listen, and maybe I can make it easier for somebody else. So Mr. Colbert, I want you to do something for me. If you know somebody who's gay, you tell them about me, and maybe it will make their lives easier. You'll be helping me a lot." He puts his hands in his lap, and looks straight at the camera. "That's really all I wanted to say. Thank you for having me on your show." (hetrez 2012)

[3.4] Similarly, autoschediastic's story "For America" (2010) combines social justice and romance plots when Steve proposes to Tony because he wants not only to marry the man he loves but also to make a public stand for what he believes in. Many other stories play out similar plots by describing political protests and, often, political fallout as Steve or Tony receives negative press because of their relationship. These plots not only depict current social reality but provide a series of "what ifs" for the reader—a different sort of AU or continuity that can be conjoined with our own as a new aspect of shared reality.

[3.5] Some fans add text to clips from the films or interviews with the actors to reinforce this shared reality. If the viewer doesn't know the original context of the visuals, it is astonishingly easy to believe that the combination of image and text is a real quotation rather than a constructed fan work. One fan, for instance, added a subtitle to footage of Chris Evans appearing on an episode of The Late Show with David Letterman. Evans actually said, "Aquaman and I are moving to New York to get married," but the subtitle changed "Aquaman" to "Iron Man" (figure 3). In the new context, the actor Chris Evans can be viewed as his character Steve Rogers; as in the fictional exchange on The Colbert Report in hetrez's story, the mix of fictional characters with real people creates an element of cognitive control—or closure—for the viewer or reader, allowing her within the newly shared universe of fandom. The characters have stepped out of the comic book panels into a blank space that can be filled by the fans. Similarly, canonical texts in the comics, such as the picture of Iron Woman's marriage to Captain America, demonstrate what happens outside the characters' own books: this scene appeared in a Fantastic Four comic rather than in Captain America, Iron Man, or The Avengers, allowing readers to view the story from outside the characters' own space—much as fan fiction does.

Figure 3. GIF of Chris Evans on The Late Show with David Letterman, July 14, 2011, edited by fan lawyerupasshole (2011).

[3.6] The world depicted in fan stories is not a utopia of acceptance but rather includes fraught experiences that most readers will have observed (if not actually lived) themselves. In many slash fandoms, the romances are viewed as if from a distance, but within Captain America/Iron Man fandom they gain a new meaning because of the historical baggage inherent in the characters. It is all but unprecedented for fandom to have a political message so inextricably bound up with a mainstream text like the Avengers. (In contrast, K/S fans in the well-documented Star Trek fandom were always only a tiny percentage of fans within a small, intense fandom.) Online dissemination of texts through social media platforms such as LiveJournal and Tumblr makes even people outside of fandom aware of the pairing. The hash tags of blog entries and other shared media sites can quickly lead readers from general fandom to slash fandom, providing another sense of sharing and another way to experience fan texts.

[3.7] Queering texts through fan fiction is the traditional method of fan revision, whether through slash or the use of AUs. AUs as a subgenre place the characters in a new setting or time line; they give fan writers a new avenue to explore not only what makes the characters or the pairing work but also what the pairing represents as a function of contemporary commentary on issues like the repeal of "don't ask, don't tell." If the Marvel: Civil War and Ultimates lines are a conscious critique of the current antiwar movement, then similarly fan fiction is a critique of the predominant comics culture. If canonical AUs provide one sort of social commentary, fan-created AUs create another. AUs within the slash subculture thus provide a space for fans to air their concerns about feminist and LGBT issues, much as the original comics provided a haven for war protestors during a period when popular culture was silent on the topic or forthrightly hawkish. They demonstrate how slash fans present and articulate their political concerns through the mode of fandom itself, and examining them gives us a more comprehensive view of how we can read past the constraints of both text and panel.

[3.8] The emblem of Steve/Tony fandom is a split circle, with one half formed by Cap's shield and the other half by Iron Man's arc reactor. It is perhaps notable that the shield prototype seen in Iron Man 2 has a more than passing resemblance to this emblem (figure 4). Readings of the prop as a deliberate shout-out by the film's creators to Steve/Tony fandom demonstrate an awareness of creators' own co-option of fans/fan service that appears to a growing element in popular culture as a whole.

Figure 4. Prototype of Captain American's shield in Iron Man 2.

[3.9] The rapid growth and transition of the fandom—from comics to movies, from hidden to open through the use of new social media—provides a fascinating record for media scholars. The exact nature of the fandom's impact, if any, has yet to be demonstrated, but for this brief moment at least, a traditionally obscure part of fandom, slash, is mainstream. Fans avoid Scott McCloud's "limbo of the gutter" to allow the various forms and aspects of the Avengers to transform into a more meaningful narrative—one that encompasses both the real world we experience and the dozens of other universes possible in comics, film, and fandom.