1. Introduction

[1.1] One of the central points of interest within fan studies has been the idea that media fans were among the earliest spectators to shift from passively consuming or even actively reading media texts to creating works of their own that extend or comment on those texts. As Henry Jenkins explains in Textual Poachers (1992), "Fandom blurs any clear-cut distinction between media producer and media spectator, since any spectator may potentially participate in the creation of new artworks" (246–47). Fans were thus early adopters of the practices that characterize participatory culture. For many scholars, fans are interesting precisely because of these participatory and creative practices.

[1.2] Yet even as we celebrate fans' propensity to make things, scholars have often paid more attention to fans as spectators than to fans as producers. Kristina Busse and Karen Hellekson observe that in the decade or so following Textual Poachers, "most essays in fan fiction studies focused on fanfic as an interpretive gesture, thus using fan fiction to gain further insight into a particular source text" (2006, 20)—an approach that foregrounds fan reading and downplays fan writing. We can see a similar tendency in recent work on vids: Francesca Coppa's history of the development of vidding, for example, argues that vids function as media criticism—"thousands of vids have been made analyzing popular source texts" (2008, ¶1.4)—and specifically as responses to the "representational tensions" (¶2.20) at the heart of Star Trek and still present in many subsequent shows. Coppa does represent fans as creators—her essay is an indispensable account of the inventiveness, hard work, and technical skill that early vidding required—but her emphasis is ultimately on vids as fans' reactions to media texts.

[1.3] Given that many academics working in fan studies have backgrounds in media studies and/or literary studies, this attention to the relationships either among texts or between texts and their readers or spectators is not surprising. But that attention, while valuable in its own right, tends to obscure the fact that while fan creators are audiences, they also have audiences. A vid is, as Coppa has explained, "a visual essay that stages an argument" (2008, ¶1.1), but for whom, exactly, is the argument staged, and what is the role that that audience plays in the argument's construction and reception?

[1.4] In this essay, we begin to theorize the vidding equivalent of what Marilyn Cooper (1986) calls the ecology of writing, a concept from composition studies that allows us to examine vidding and vidwatching as activities "through which a person is continually engaged with a variety of socially constituted systems" (367). In order to continue Coppa's project of studying "broad continuities in vidding practice" (2008, ¶1.5), we must look at the roles fannish audiences play in shaping that practice: the social and rhetorical contexts for both the production and reception of vids, the constraints and possibilities generated by fannish conventions of interpretation. Creation does not happen in a vacuum; a vid is an individual's (or small group's) argument about a text, but it is informed by, and interpreted in terms of, other fans' ideas about that text, and those arguments and ideas are worked out within the multiple overlapping discourse communities that constitute fandom. Although a complete application of this ecological model is beyond the scope of the present essay, we do examine selected fan discussions of the TV series Hawaii Five-0 (2010–present) to show how these discussions, in addition to being a form of fannish activity in their own right, establish what counts as evidence for a particular fannish interpretation and thus enable vidders to make effective rhetorical choices, as lamardeuse does in her vid "Something's Gotta Give.". Such discussions are therefore a key part—though only one part—of the ecology of vidding.

2. Fandom as ecology

[2.1] Cooper's ecological model of writing is grounded in the assumption that "language and texts are not simply the means by which individuals discover and communicate information, but are essentially social activities, dependent on social structures and processes not only in their interpretive but also in their constructive phases" (366). The term ecology "encompasses much more than the individual writer and her immediate context"; it allows us to explore "how writers interact to form systems" and to consider how "all the characteristics of any individual writer or piece of writing both determine and are determined by the characteristics of all the other writers and writings in the systems" (368). The term also registers the inevitability of change: "An important characteristic of ecological systems is that they are inherently dynamic; though their structures and contents can be specified at a given moment, in real time they are constantly changing" (368). The concept as Cooper describes it overlaps in significant ways—including, of course, the metaphor for which it's named—with the idea of media ecology developed by Marshall McLuhan, Neil Postman, and Walter Ong (see Strate 2004); because we are primarily interested in the implications of an ecological model for the study of composing (rather than, for example, the more literary concept of intertextuality), our usage follows Cooper's.

[2.2] At the time Cooper's article was published, composition studies needed the concept of ecology as a corrective to the field's narrow focus on the cognitive processes of individual writers; Cooper's work was part of a massive and lasting shift toward thinking of writing as a fundamentally social process. Fan studies in the present historical moment needs the concept as a different kind of corrective: We need more discussions of the social or collaborative nature of fandom that don't erase individual creators by collapsing collaboration into mass authorship, as Paul Booth does when he insists that "the 'author' of a blog fan fiction is not a fan, per se, but rather a fandom" (2010, 6). As Alexis Lothian points out, vids are too often "perceived as an undifferentiated feature of the online 'public' domain" (2009, 131). Such erasure of fan authorship, with its troubling gendered implications, is a real danger in a culture that tends to regard YouTube videos as a genre rather than as individual authored works, and it has been a real feature of academic work that, Deborah Kaplan observes, "elides the texts in favor of the community" (2006, 135). At the same time, however, many analyses of individual fan works privilege individual authorship: They address collaborative meaning making only at the point of reception, not as a condition of production. Thinking of fandom as an ecology will, we hope, encourage scholars to articulate how fandom's "individual voices, creative works, philosophies, resistances, and cultures" (Cupitt 2008, ¶4.4) not only coexist but interact.

[2.3] The ecology metaphor helps us to think of fandom as a system (or series of systems) within which all fans participate in various ways: as readers, writers, vidders, vid watchers, posters, commenters, lurkers, essayists, artists, icon makers, recommenders, coders, compilers of images and links, users and maintainers of archives and other fannish infrastructures, and so on. An ecological model thus offers an alternative to the theoretical models of fandom that, as Matt Hills has shown, define fans solely as producers and so "attempt to extend 'production' to all fans" (2002, 30). Further, it provides a framework for thinking about the ways in which, as Kristina Busse has argued, "people as well as stories become central to fannish interaction" in LiveJournal-based fandom (2006, 214). It gives us a way of describing relationships among fans that is simultaneously broader and more precise than the concept of community, which, as James Paul Gee observes, "carries a rather romantic connotation which it should not have" (http://henryjenkins.org/2011/03/how_learners_can_be_on_top_of_1.html). Because it directs our attention to real social contexts—contexts that are, as Cooper (1986) points out, not unique or idiosyncratic but connected with other situations (367)—it encourages us to observe the relationship of vidders and other fannish producers to their audiences, to consider the ways in which those audiences are not abstract rhetorical constructs but real people with whom vidders may interact and communicate in a variety of capacities.

[2.4] Much has been written about the conversational and communal nature of fandom in general (Hellekson and Busse 2006). Busse and Hellekson (2006), for example, explain that they are less interested in the psychology of individual fans (a trend seen in the work of Matt Hills and Cornel Sandvoss) than in "the collective nature of fandom, its internal communications, and the relationship between fans that arises out of a joint interest in a particular text" (23). While we share this interest, we prefer the term collaborative, which implies individuals working together for a common purpose, to collective, which suggests an undifferentiated group, and we resist Busse and Hellekson's insistence on "the ultimate erasure of a single author" (6). Nevertheless, we take our cue from them and from scholars such as Rebecca Black (2008), whose analysis of the composing practices of three specific fan fiction authors locates those practices within larger fields of literacy. Like them, we aim to discuss fan works as "part collaboration and part response to not only the source text, but also the cultural context within and outside the fannish community in which it is produced" (Busse and Hellekson 2006, 7).

[2.5] While the collective nature of fandom has been much discussed, considerably less has been written about the social nature of vidding. Jenkins notes that vids "focus on those aspects of the narrative that the community wants to explore" (1992, 249); Coppa calls vidding "a form of collaborative critical thinking" (2008, ¶5.1); Tisha Turk describes making and watching vids as processes of "collaborative interpretation" (2010, 89). But to date, research on vids has done relatively little to illuminate how that collaboration works or how those conversations happen. Indeed, we may talk most about this collaboration when it fails to happen—when, as Jenkins (2006) and Julie Levin Russo (2009) discuss, a vid is removed from its "interpretive landscape" (Russo 2009, 126) and misunderstood by a nonfannish audience unprepared to make sense of it. Many readings of vids therefore focus on what a viewer must know in order to understand a particular vid. In her analysis of Counteragent's "Destiny Calling," for example, Cupitt establishes that the vid is "a snapshot of the fannish zeitgeist of that moment" (¶3.9) and it "requires a large body of contextual knowledge" in order to be fully understood (¶3.10). Similarly, Katharina Freund's examination of "Still Alive," also by Counteragent, emphasizes that "the viewer must be extremely familiar with Supernatural, vidding, and online fandom in order to separate all these shots and their contexts" (2010, ¶4.1) and the vid "will always be meant for a very specific audience at a very specific time in this fandom's history" (¶5.1).

[2.6] Our argument is intended to amplify and extend these ideas. Cupitt's and Freund's discussions of context, and especially their shared emphasis on historical context, focus on the reception of vids; we wish to suggest the value of also looking at the fannish ecology as a condition for the production of vids. What can a vidder anticipate about how an audience will make sense of her vid? What can she assume, or how can she learn, about the significance her audience will ascribe to particular clips? We are interested not only in the knowledge fans must have in order to interpret a vid, but also in how fans acquire and share that knowledge, because vidders make creative and aesthetic decisions based in part on the readings and interpretations in circulation within a fandom. Busse and Hellekson's model of fan creations as works in progress, in which the work ultimately shifts from creators to readers, can thus be understood as having an earlier phase, which Busse and Hellekson imply but do not articulate: the collaborative work of sharing interpretations that precedes and enables the composing of a particular text. In an ecological model, context is not something that simply exists; it's something that the participants in the ecological system create through their various fannish activities and, importantly, the textual traces of those activities.

3. Interpretive conventions

[3.1] One element of this ecological system is the set of interpretive conventions that guide the creation and reception of texts. As Cooper reminds us, these conventions "are not present in the text; rather, they are part of the mental equipment of writers and readers, and only by examining this mental equipment can we explain how writers and readers communicate" (365). In fandom, these conventions are generated, contested, updated, and circulated through the discussion and analysis of media texts and the creation and consumption of fan works (see Kaplan 2006, 135–36). As we've seen, such conventions are important for vid watchers (Jenkins 2006, Russo 2009, Cupitt 2008, Freund 2010), but they are as least as important for vidders, because vidders who want their vids to be understood must work with—which is not to say blindly conform to—at least some of these conventions. As Peter Rabinowitz observes, "There are no brute facts preventing an author from writing a religious parable in which a cross represented Judaism, but it would not communicate successfully" (1987, 24). Vidders, like authors, must negotiate the interpretive conventions present in their ecologies.

[3.2] Some of these interpretive conventions are grounded in fannish responses to individual shows and movies, in specific arguments and discussions about how characters, relationships, and story lines ought to be interpreted. Others have to do with patterns across media texts: When fans read certain interactions in, say, Hawaii Five-0 as indicating that the two main characters (both male) are romantically or sexually interested in each other, they draw not only on the interactions of those two characters but also on similar interactions between characters in Star Trek, The Professionals, Starsky and Hutch, Highlander, The Sentinel, Due South, Stargate: SG-1, Stargate: Atlantis, and so on. Still other conventions, such as ways of signaling which character's point of view is being expressed, are specific to vids as a genre. Our analysis in this essay will focus primarily on the first of these three sets of conventions: those having to do with how established fannish readings are used by both vidders and vid watchers to generate a great deal of meaning out of small collections of short clips.

[3.3] Vids require audiences to process many different kinds of information, including the visual content of clips (what's happening in the frame), the context of clips (what's going on in the original source), and the juxtaposition of clips within the vid (why one clip precedes or follows another). The meaning of purely visual content is generally accessible to a casual fan or even a nonfan: when characters argue or smile, when they punch or kiss each other, the significance is usually clear, and additional interpretive guidance is usually provided by the lyrics against which the visuals are set, the tone of the music, and the mood or message of the song as a whole (see Coppa 2008, ¶1.1). Understanding the contextual meaning of clips, as Cupitt and Freund suggest, requires considerable familiarity with the source. And making sense of the juxtaposition of clips requires viewers to recognize whether a particular sequence of clips is intended as a narrative, a plot summary, a comparison, a representation of cause and effect, an establishing of mood or theme, or any of the other functions the sequence might serve within the vid.

[3.4] Most vids include both clips whose significance is primarily visual and clips whose significance is primarily contextual; exact proportions vary depending on the nature of the vid and the goals of the vidder. The Clucking Belles' "A Fannish Taxonomy of Hotness," for example, relies almost entirely on visual information rather than context because, as Coppa explains, the vid "isn't about people; it's about tropes" (2009, 108). Rowena's "Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Abridged)," by contrast, is made up almost entirely of clips that encapsulate events and even whole story lines from Buffy in order to produce the effect of covering all seven seasons in under three and a half minutes.

[3.5] Of course, visual and contextual meaning are not mutually exclusive; many clips convey visual information even to a casual viewer and call up for fans specific conversations, interactions, emotions, relationship developments, or plot points. To illustrate, we provide two examples of clips frequently used in vids for their respective fandoms.

[3.6] First, in Buffy the Vampire Slayer vids, Buffy's dive into blue-white light is a striking visual regardless of whether one knows the significance of the shot in the original show.

Figure 1. Image from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, 5.22 "The Gift" (2001). [View larger image.]

[3.7] In context, this image carries considerable emotional as well as visual weight: Buffy is jumping to her death to save her sister and the world.

Video 1. Buffy says goodbye to her sister. Buffy the Vampire Slayer 5.22, "The Gift" (2001).

[3.8] For a fan of the show, this clip—even just a fraction of the clip, even without sound—has the potential to evoke a host of events, feelings, and themes—even perhaps specific dialogue. Not all scenes from the show are so well known within the fandom, but in this case, because of the clip's emotional impact and its importance to the show's narrative arc, a vidder familiar with the fandom can be confident her audience will recognize it and respond accordingly (note 1).

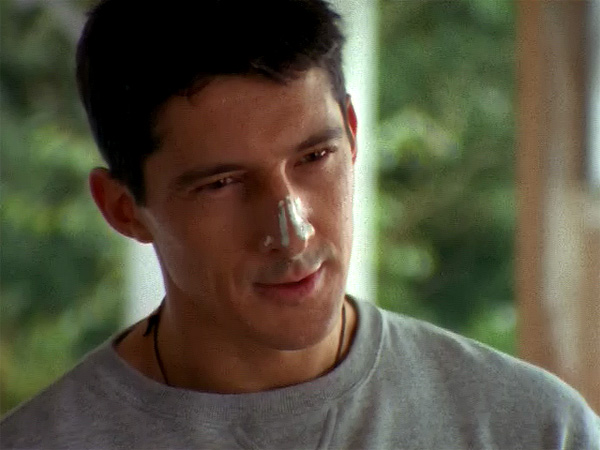

[3.9] Second, in Highlander vids that suggest a romantic and/or sexual relationship between the characters Duncan and Methos, the scene in which Duncan daubs paint on Methos's nose is almost guaranteed to appear.

Figure 2. Image from Highlander, 4.10 "Chivalry" (1995). [View larger image.]

[3.10] Even without context, the image suggests friendly teasing. As with the clip from Buffy, however, viewers who know its context can supply additional emotional significance.

Video 2. Duncan and Methos discuss honor and survival. Highlander, 4.10 "Chivalry" (1995).

[3.11] Although this scene doesn't have the same apocalyptic narrative significance as Buffy's death, it is nonetheless a scene of considerable consequence for fans of the Duncan/Methos pairing: Methos expresses concern for Duncan's well-being even while insisting he worries only about himself. For vidders, the clip is especially significant because it is one of a relatively small number of scenes in which the two characters appear on screen together. It is worth noting, however, that reactions to the use of this clip changed over time as some vid fans began to feel it had been overused. Alexfandra's Highlander vid "It's All Been Done Before" offers a particularly amusing and pointed critique of the alleged overuse: this clip (along with several others) features prominently at the vid's first chorus—and then again at the second chorus.

[3.12] While both fan fiction and vids rely on familiarity with characters' attributes, circumstances, and history, most vids also benefit from the recognition of specific gestures, expressions, and conversations from the source text. Viewers must recognize which scene a particular clip is from, recollect its significance, decide whether or to what extent that context is meaningful for a particular clip, and apply that meaning to the vid—all on the basis of very limited information, because a typical clip is usually between 1 and 5 seconds long and may in some vids be considerably shorter. And the relative brevity of clips means a viewer's process of making meaning must happen so quickly as to be nearly unconscious.

[3.13] What we wish to emphasize is that, in most cases, this meaning-making is not purely individual; rather, it involves a certain amount of collaboration and consensus. Recognition of context requires familiarity with the source, and familiarity requires repetition. That repetition may take the form of an individual fan rewatching entire episodes or specific scenes (see Coppa 2009 on the pleasures of the VCR), but it can also be communal or collaborative: for many fans, it includes reading and/or posting episode recaps, fan fiction, or informal analyses. All of these interpretive acts help not merely to define fan readings of a text but to establish particular on-screen actions and conversations as evidence for those readings. Repetition is thus one of the key ecological processes by which a group of fans comes to some consensus about which moments and visuals are critical to their reading of the show (note 2). This consensus is likely to influence a vidder's choices about how best to arrange her narrative or present her argument to that interpretive community.

4. Case study: "Something's Gotta Give"

[4.1] A complete discussion of the ecology within which lamardeuse's "Something's Gotta Give" was created, distributed, and viewed would need to consider the relationship of vid, vidder, and audience not only to fannish discussions of Hawaii Five-0 but also to the other shows the fans have watched, the fan fiction they have read and written, the other vids they have watched and made, the reception histories of those stories and vids, the growing body of fan discussions of vidding practices and aesthetics—all the social and discursive systems within which the fans and the vid are situated.

[4.2] Because such a discussion is not possible within the constraints of this essay, we will instead focus on a small subset of these topics. First, we briefly address some of the interpretive conventions, both general and fannish, that lamardeuse invokes by including clips that require no particular contextual knowledge. Second, we identify selected clips from the vid that require or reward contextual knowledge; we examine representative fannish discussions of those moments in order to highlight the shared repetition those discussions enact and the associations that they create between dialogue and visuals as evidence for a particular fannish reading. Third, we analyze an instance in which lamardeuse uses largely undiscussed clips, effectively decontextualizing those clips in the service of her own narrative and reminding us that fannish consensus informs but cannot determine a vidder's decisions about how best to communicate with her intended audience.

[4.3] Our examination of fannish discussions of Hawaii Five-0 draws primarily on posts and comments on the LiveJournal and Dreamwidth sites (note 3). These sites are major locations for fannish discussion in general, and because they are sites to which the vidder herself posts and on which she publicizes her vids, they are central to the ecology within which this particular vid was produced and received. Posts to LiveJournal and Dreamwidth may be either short or quite long and can include text, images, and embedded video; comments range from single short sentences to several long paragraphs. In these posts and comments, we can see fans compiling evidence for their readings of the show. This work is collective: consensus emerges as individuals identify particular scenes as significant and other fans ratify that significance (with varying levels of universality and enthusiasm) in their comments, echo it in posts of their own, and reiterate it in various ways, including the creation and use of user icons.

[4.4] In the case of "Something's Gotta Give," the vidder's own LiveJournal is an especially important part of the fannish ecology. Because of her geographical location, lamardeuse usually sees episodes of Hawaii Five-0 several hours before most other viewers. Immediately after a new episode airs in her time zone, she posts reactions and spoilers in her journal. For many fans, especially those who enjoy getting a sneak peek at new episodes, these posts are ground zero for an explosion of fannish excitement. In addition to these preview posts, lamardeuse posts detailed recaps of most episodes, usually featuring dozens of screen caps; these recaps, too, are quite popular, typically generating more than 40 comment threads between the LiveJournal and Dreamwidth posts. As a result, lamardeuse's audience for her vids includes a significant number of people with whom she regularly communicates about Hawaii Five-0; she can be fairly confident her intended viewers will not only share her general perspective on the show's characters, but also recognize certain visuals as strong textual support for the pairing featured in "Something's Gotta Give."

[4.5] The microblogging platform Tumblr is another increasingly important locus for the expression of fannish enthusiasm. Tumblr posts are typically quite short—a single image, animation, quotation, comment, or short video clip—and the proportion of images to text is much higher than on LiveJournal and Dreamwidth; uptake is usually signaled through "liking" and reblogging rather than commenting. Because post dates are sometimes relative ("3 weeks ago") rather than absolute, it can be more difficult on Tumblr than on LiveJournal and Dreamwidth to track responses to specific episodes after the fact. But when followed in real time, blogs such as http://fuckyeahhawaiifive0.tumblr.com/, which accepts submissions of content from all over Tumblr, offer venues for fans to recirculate key images and scenes and thus establish their interpretive value.

[4.6] We turn now to the vid itself (video 3).

Video 3. lamardeuse's Hawaii Five-0 fan vid, "Something's Gotta Give" (2011).

[4.7] The general argument of "Something's Gotta Give" is readily apparent even to viewers unfamiliar with Hawaii Five-0 in large part because, thanks to lamardeuse's song choice, it represents the Steve McGarrett/Danny Williams relationship in terms of the classic trope of two people who don't seem to get along but fall in love anyway. The vid is a romance, narrated from Danny's perspective, in which conflict and opposition between an irresistible force and an immovable object gradually give way to attraction: "someone's gotta be kissed." For fans, even fans unfamiliar with this show, the vid makes particular sense in terms of the fannish interpretive paradigm, usually summarized as "they are so married," in which bickering or even outright arguing (in conjunction with acts of respect and understanding) indicates a relationship so intimate that politeness is redundant: The characters know each other too well to stand on ceremony.

[4.8] The romance presented in the vid is especially accessible because both halves of the story—conflict on one hand, partnership on the other—are visually encoded in many of the clips lamardeuse chooses. The visuals in the vid's introduction and first verse, in particular, emphasize conflict: Danny punches Steve, Steve twists Danny's arm behind his back, Danny yells at Steve, the two of them glare at each other in exasperation. The visuals in the second verse, by contrast, suggest friendship, respect, affectionate teasing: Danny and Steve smile and chuckle at each other, clink their beer bottles together, shake hands. And lamardeuse maintains the tension between these two aspects of the relationship all the way through the vid's final clips.

[4.9] But for fans of a show, much of the pleasure of watching a vid lies in supplying more meaning than the visual information alone conveys. At the end of the first verse (0:31), for example, Danny gestures dismissively at Steve and walks away while Steve lifts his hand and furrows his brow inquiringly.

Figure 3. Danny walks away from Steve. Hawaii Five-0, 1.09 "Po'ipu" (2010). [View larger image.]

[4.10] The visual conveys information on its own: a disagreement of some kind, Danny irritated for a reason he doesn't want to explain. But fans of the Steve/Danny pairing have established this scene as important because Danny's irritation has to do with Steve's interactions with an old buddy from the Navy and can be read as jealousy—a reading that the show's dialogue supports. In her recap of the episode, lamardeuse (2010f) quotes the dialogue from this clip:

[4.11] Steve: Are you jealous?

Danny: No.

Steve: That's jealousy!

Danny: (storming off in a huff) NO!

[4.12] What's important here is not just that the vidder perceives this theme and moment as meaningful (and includes multiple screen caps from the scene in her episode recap), but that other fans share this perception. In a response to lamardeuse's preview post (2010e) on the episode, gottalovev sums up the reaction of Steve/Danny fans when she remarks that "seriously. the jealousy, it could be seen from SPACE." Nearly a third of the commenters on the episode discussion posts for the LiveJournal SteveDannoSlash and Hawaii5-0Slash communities mention the jealousy as well: as alicebluegown16 comments, "I mutter to myself, 'Jeez, Danno. Jealous much?' And then Steve says it! God, I love these writers and their whole hearted embracing of the subtext" (LiveJournal comment in hawaii5-0slash, November 15, 2010). Clearly, this is a clip that's likely to be immediately recognizable to fans of the pairing.

[4.13] Perhaps even more important, however, are the vid's uninformative visuals, including some at key moments in the vid; in these instances, the vid depends entirely on viewers to supply the contextual significance of the conversations and character interactions from these scenes—a strategy that works for the vidder because, as we will see, the vidder is well aware that many of these moments are precisely the ones that her audience is likely to have revisited. We will limit our discussion to three such moments in the vid; fans of the show will no doubt recognize many more.

[4.14] At the beginning of the second verse (0:40), lamardeuse has placed a clip that viewers who don't know the show would probably find puzzling (we certainly did when we first watched the vid): Steve in the dark with a gash on his face and an ambiguous expression. The clip's brevity makes it even harder to interpret. And it's followed by a relatively long clip, clearly from the same scene, of Danny smiling, pleased and perhaps a little bashful. Danny's response is fairly easy to read, but to what, exactly, is he responding?

Video 4. Steve McGarrett needs to pick better friends. Hawaii Five-0, 1.09 "Po'ipu" (2010).

[4.15] After Steve is betrayed and attacked by a buddy with whom he served in the Navy SEALs, Danny insists that Steve needs to do a better job of picking his friends; Steve responds, "Tell me about it—I picked you, didn't I?" For fans attuned to signs of affection between the two characters, Danny's exasperation and Steve's teasing were quickly adopted as key evidence of that affection. In and_ed's episode recap (2010), this dialogue is quoted approvingly; elandrialore both quotes the dialogue and sums up her reaction: "I AM SO IN LOVE WITH THIS SHOW, OMG!" (elandrialore 2010b). The sentiment is widely shared; hai_di comments on and_ed's episode recap that "'Tell me about it, I picked you, didn't I?' were my very favorite lines" (LiveJournal comment in and_ed 2010). Over at the Hawaii5-0Slash community discussion post, commenters respond similarly: "I picked you, didn't I. Squeeeeeeee" (indigocat, November 15); "That line, and Danny's corresponding smile…had me also smiling and sqeeing" (michele659, November 15); "Really loved the end banter, when Danno told Steve he really knew how to pick his friends & Steve said 'I picked you, didn't I?'" (cmariad, November 15). lamardeuse can rely on fans of the pairing to understand why this scene would warm Danny's "old implacable heart" precisely because those fans have established among themselves what the scene means.

[4.16] At the end of the vocal bridge, we encounter a series of clips in which Danny and Steve, both in dress uniform, face each other; Steve nods and says a word or two; and Danny smiles. A fannish viewer—even one unfamiliar with the source—can guess that something important just happened here, but the details can only be filled in by viewers who know that Steve has showed up to support Danny at the funeral of a friend and former partner.

Video 5. Steve knows Danny. Hawaii Five-0, 1.08 "Mana'o" (2010).

[4.17] Steve's "I know you"—with all the respect and trust it implies—was, as lamardeuse noted in response to a comment on one of her posts about the episode, "THE LINE HEARD ROUND THE FANDOM" (2010c). More than one fan asserted the scene's similarity to the end of the film An Officer and a Gentleman (1982) and invoked its theme song, "Up Where We Belong" (sheafrotherdon 2010; cottontail in elandrialore 2010a; lavender_basil in lamardeuse 2010d); this association is of course grounded at least as much in Steve's uniform as it is in the scene's dialogue. In this context, the clip is an overwhelmingly appropriate choice to pair with a lyric in which the singer confesses he won't be able to ignore his attraction much longer: the scene's meaning, as determined by fans of the pairing, is explicitly romantic, and clips from the scene are rendered instantly recognizable by the visual of Steve in uniform.

[4.18] At the end of the instrumental (1:58), we encounter a series of clips in which Steve gestures as if he's giving something to Danny, Danny smiles, and Steve smiles back. While the smiles suggest that this is a scene of the two of them getting along and feeling friendly, there's nothing in the visuals to indicate why these clips are important enough to conclude the vid's instrumental section. But for fans who recognize that gesture, the significance is well established.

Video 6. "It's a term of endearment." Hawaii Five-0, 1.06 "Ko'olauloa" (2010).

[4.19] Steve's admission that "When I say, 'Book 'em, Danno,' it's a term of endearment" is notable both because it legitimates the fannish process of reading more into the dialogue than is actually said and because this line and Danny's response make explicit the characters' fondness for each other; as such, it produced considerable fannish excitement when the episode first aired. In her initial reaction post about this episode—the one posted hours before most of her fellow fans had even seen the episode—lamardeuse quotes this line and then comments: "THAT IS THE ACTUAL LINE. I AM NOT SHITTING YOU. I AM NOT MAKING THIS UP. OH MY FUCKING GOD. DYINGGGG HERE" (2010a). (In keeping with the tone and excitement level of this post and lamardeuse's preview posts in general, many of the comments also feature caps lock and multiple exclamation points.) The somewhat calmer follow-up post (2010b), a fuller recap of the episode, features five screen caps from this scene: one of Steve gesturing, two of Danny responding and then smiling, and two of Steve beaming at Danny—a reinscription that helps ensure fans will be able to identify the scene even without dialogue. "I HAVE PLAYED THIS FIFTY TIMES NOW AND I STILL CANNOT BELIEVE IT ACTUALLY HAPPENED," lamardeuse notes, and her commenters agree: "I totally had to rewind several moments multiple times because, WOW!" (ionaonie); "And then that final Steve&Danny scene that I had to rewatch 2 or 7 times" (giddygeek). And leupagus and her commenters concur: "I can't even tell you how many times [we] watched that scene, but it was a lot, and it got better EVERY TIME" (leupagus 2010); "And that look Steve gave Danny at the end, over the 'term of endearment' line? I rewatched that like, 5 times, I'm sure" (and_ed in leupagus 2010).

[4.20] It's no stretch, then, to suggest that fans of the pairing would recognize this scene, know it well, and find it an appropriate emotional climax to this section of the vid; many fans clearly rewatched the clip, and even those who didn't are likely to have reencountered it in episode reviews on LiveJournal or Dreamwidth or screen caps on Tumblr. This willingness to rewatch key scenes and the resulting ability to recognize even small snippets of those scenes in vids is an essential part of the fannish ecology within which vidders work.

[4.21] But in addition to drawing on context that fans already know, lamardeuse also recontextualizes certain clips by combining them in ways that deemphasize their connection to the original episode plots and contribute to her own narrative of antagonists moving toward romantic partnership. We see this recontextualizing most clearly at the instrumental bridge (1:38–2:01). The bridge, as we've seen, concludes with clips from the contextually important conversation about terms of endearment. It opens, however, with scenes of action rather than conversation; what matters here is not which bad guys Steve and Danny are fighting but the fact that the two of them are functioning effectively as partners. These clips set the tone for the rest of the bridge: beating up bad guys together, walking side by side, working as a team. The fight scene that yields a relatively long sequence of clips in the vid (1:44–1:48) doesn't rate even a single screen cap in lamardeuse's recap of the episode; for fans focused on the Steve/Danny pairing, it's a scene that's not particularly interesting on its own. But in the context of the vid, lamardeuse makes it interesting: the shots mean something different in the vid than they do in the episode. These clips are dictated not by what the audience already knows or remembers about this relationship but by the needs of the vidder's narrative. "Something's Gotta Give" is not a haphazard collection of greatest hits clips; in lamardeuse's selection of song, her use of that song to structure the vid, and her strategic juxtaposition of relatively undiscussed clips at the song's instrumental bridge, we see the choices of an individual artist.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] Scholars within fan studies have generally maintained, with varying degrees of insistence, that fan texts are collaborative, but our understanding of the mechanics of fan collaboration, especially in vidding, is still incomplete. An ecological model of composition lets us have it both ways; it encourages us to pay attention to both the individual and social aspects of authorship and, perhaps more importantly, to the interactions between them. Studying the ecology within which vidders produce, including the generic and show-specific interpretive conventions that guide audience perception and thus vidder creation, allows us to think in new ways about vidders' creative processes and the rhetorical work that goes into vidding.

[5.2] Developing an ecology of vidding can also begin to strengthen our understanding of the roles of audiences outside fandom. Contemporary composition scholars such as Erin Karper (2009) and Traci Zimmerman (2009) have already begun the project of reimagining audiences, but their work tends to reify the distance between composer and audience that they are attempting to reduce. A model of an audience who is active in and even integral to the composing processes of online authors would begin to alleviate this problem. As a field of inquiry, composition studies has much to offer the study of online fandom, but we suspect that it also has much to learn.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] We are deeply grateful to lamardeuse for her gracious permission to discuss her vid; to the many fans cited here for permission to quote from their posts and comments; to Cate for the vid recommendation, the whirlwind introduction to Hawaii Five-0 fandom, and the indispensable list of links; and to Laura Shapiro for invaluable conversations about vidding and audience.