1. Introduction

[1.1] Stuart Hall (1992) notes that popular culture is a complex political arena wherein the codes of Black identity are perpetually negotiated. Jacqueline Bobo (1988) demonstrated that as cultural readers from a subordinated position, Black women produce complex, affective, and intellectual responses to media. Black women can have fierce debates about Black womanhood and its claims to authenticity, on and off the screen. When a diverse group of those women performs ideological labor through one character, what are the inevitable discourses and disaffections? The heterogeneity of their standpoints about racialized gender identification can create a kaleidoscopic canvas of conversation but also spark contention. I interrogate the meaning-making Black women participate in through their affective and disaffective fan practices around Scandal's (2012–18) Olivia Pope. Through my encounters as blogger katrinapavela, I explore the ways that fantagonisms coalesce around intraracialized debates within blackness. By delving into the roots of the divergences, I contextualize them in broader affective and sociological terms of intersectionality, taste hierarchies, and disaffection as social bonding among fans.

[1.2] By considering Black women's fandom from an axiomatic perspective, I embrace the inevitability of conflict by looking at the major themes around which schisms can develop. As the first terrestrial network series in thirty-seven years starring a Black woman, there were a lot of expectations hanging on ABC's series Scandal and its main character, Olivia Pope. Those expectations spill from the fictional series, becoming the basis of judgments against the fans themselves. I interrogate the identity tensions of Black womanhood in America, from the ideological expectations of those within the group itself, and how Scandal's textual and metafandom politics lend shape to these disagreements and factions.

2. Fantagonisms and debates about antifandom

[2.1] "Fantagonisms" is a term coined by Derek Johnson (2017), who details the differing constitutive hegemonies of fandom. The term merges "fan" and "antagonism" to express specific tensions within communities of fan practice around textual meaning and struggles to shape production to their expectations. The term "antifan" is closely related, which predates Johnson's term. Coined by Jonathan Gray (2003), "antifan" ostensibly identifies fans whose relationship to a media object (or to fans of that media) is almost exclusively antagonistic. In expanding his theory, Gray (2019) develops a tentative taxonomy of antifandom that embraces multiple modalities and orientations to media (and other fan objects). Gray recognizes that disaffective relationality (bad media, disappointment, fan aggression) has something to teach us about fandom writ large. I employ fantagonism as a merger between antifan and Johnson's (2017) fantagonism. Studies that have explored fantagonism or antifandom focus on contested relationships between the fans and (show) producers or writers (Jenkins 1992; Jones 2019), fans and characters of a media property (Lotz 2014; Halladay and Click 2019), or, more recently, with the oeuvre of an auteur (Martin 2019), among others. In some instances where intra- and interfandom interactions reveal gendered concepts of the good and bad fan (Bacon-Smith 1991; Busse 2013; Stanfill 2013), race is not highlighted as a significant variable, even in instances where gender is. Those studies largely leave the interplay of race and gender logics as furtive ground for intraracial antagonism underexamined. In instances where race is explicitly factored into intrafandom aggression, it's usually about a marginalized group being labeled as the aggressor by the dominant group for raising race-based concerns (Johnson 2017; Scott 2017; Pande 2018).

[2.2] My examination of disaffection within Black women's Scandal fandom on Tumblr is broadly influenced by Henry Jenkins's (n.d.) notion of the acafan as having one foot in both academic and fan spaces. But more specifically, I draw on Patricia Hill Collins's (1986, 1999) culturally specific use of the "outsider within." This positionality is based on Black women's epistemological subjectivities within broader academia. From this position, Black women developed learned ways of seeing, narrative and linguistic patterns, and access that other scholars do not have.

[2.3] Lastly, this work is influenced by a few scholars who intimately examine disaffection and disillusioned relationships with media objects. Alfred Martin Jr. (2019) interviews self-identifying hate-watchers of Tyler Perry films. He considers how Black women's education, class, social bonding, and cultural taste levels define the contours of their dislike for Perry's films. However, those women's antifan performances did not include online spaces. Significant, too, is Louisa Stein (2019), who explores, from an acafan position, her moment of disidentification with the TV show Glee (2009–15) and its attendant affective struggles. Lastly, Anne Gilbert's (2019) and Bethan Jones's (2019) nuanced consideration of the social performance of dislike and the affective harm caused by antifan production, respectively, were helpful in this study.

3. Methodology

[3.1] The methodology used for this article is critically engaged ethnography (CEE), conducted in late 2015 on Tumblr. CEE combines critical ethnography (Madison 2005) and engaged ethnography (Pacheco-Vega and Parizeau 2018). The marriage that is CEE allows me, as a Black woman fan-cum-researcher, to place myself among the marginalized group I study while remaining critical of the framework, values, and power relations of my research environment. The CEE approach considers the insider/outsider identity of the native ethnographer and asks us to consider our multiple positionalities and subjectivities and the differences between engagement and exploitation (Pacheco-Vega and Parizeau 2018) when positioning ourselves among the researched.

[3.2] Matt Hills (2021), who wrote about fandom from an autoethnographic perspective, notes that when writing, the researcher's positionality within fandom needs acknowledgment due to biases and attachments that inform their work. Rukmini Pande (2021) goes further in a way that echoes Collins by pushing the duality of self/other and (un)belonging as a woman of color researcher among same-race fandoms. She argues that such researchers have the critical training to recognize larger structures and hierarchies, even as we "squee from the margins" (2018). Using CEE, I examine the contestations around Black femininity within the fandom arising from Scandal's characters and themes.

[3.3] This insider/outsider position results in a more complex standpoint on how ideations of Black femininity can be used to create textual dividing lines. Being a critically engaged ethnographer intentionally blurs the line between the objectivity and subjectivity of the researcher. For this reason, my own fan production and engagement with other fans on Tumblr, as katrinapavela, are offered for critical examination and reflection. As someone who was a member of Tumblr's Scandal fandom in 2012 before my return to academia in 2015, it seemed unethical to ignore my content production, relationships, and standing as a Big Name Fan (BNF) before formalizing my research. Therefore, my own motivations and attitudes are questioned.

[3.4] The data used are discursive interactions centered around a Tumblr post I made in October 2015 (https://katrinapavela.tumblr.com/post/131427238839/you-guys-i-cackled-and-then died-the-first-two). A post primarily intended to highlight creators whose content featured in an academic publication about Scandal instead became a battlefield for waging flame wars about Black femininity and its representation. Black women's voices constitute most of the data. These voices are diverse in their viewpoints on Black identity and taste hierarchies. Using Black feminism and standpoint theory as analytical frameworks, I examine the responses in search of Black identity ideologies that drive intrafandom and metafandom conflicts.

4. "[The] woman saying [this] is BLACK like us": Encounters with fantagonism

[4.1] In late October 2015, I logged into Tumblr. One of the first posts to appear on my dashboard was a (since deleted) subpost by a mutual Scandal follower. The subpost directly praised @babycakesbriauna (BCB hereafter) for how she excoriated ("dragged") an unnamed fandom member. Desperate curiosity and the desire to be entertained led me to BCB's Tumblr, wondering who her target had been and why. My heart rate increased tenfold when I came across her reblog of a post I had made earlier that evening, which had received significant engagement. I kept scrolling down to the response, my anxiety levels off the charts, hoping mine was not the targeted post. It was. Katrinapavela was the subject of BCB's dress-down (https://babycakesbriauna.tumblr.com/post/131668674331/katrinapavelababycakesbriauna). The ferocious precision of the response surprised and flummoxed me because my post had nothing to do with BCB directly nor made any circular reference to her. Yet her words went beyond disagreement into an intensely personal realm (repeated use of "you" and "your") in its publicness. A castigation disguised as intersectional intellectualism. Such a practice was not unfamiliar to Tumblr nor to the Scandal fandom there. However, I had never been the target. In some ways, BCB's public callout of my politics had much to do with the perception of me as a prominent fan in our niche world. BCB's missive blurred the lines between katrinapavela, the blogger, and Kadian Pow, the researcher, the consequences of which entailed psychic and emotional ripples extending well beyond that autumn evening in 2015.

[4.2] After reading Kristen Warner's "ABC's Scandal and Black Women's Fandom" (2015b), I was excited to see an academic piece that not only centered Black women's fandom but more acutely reflected the fan community I had known. I wanted fans to know that such an article existed and that some of their fan labor was featured in Warner's analysis (https://katrinapavela.tumblr.com/post/131427238839/you-guys-i-cackled-and-then died-the-first-two). I tagged those accounts in the post, including screenshots of the Cupcakes book cover on the first page of Warner's article and a salacious snapshot from it, which bemused me. That excerpt concerned how fans concoct and participate in shipping a romantic relationship between the actors whose characters play lovers (e.g., Kerry Washington and Tony Goldwyn are shipped in parallel with their characters, Olivia and Fitz). Warner deftly wielded fandom terminology in ways delightful and surreal. I tried to convey this to my audience in a post complimentary of Warner's piece. I used the tags to vent about the contradictory ways Warner discusses Pope as a "race-neutral character" for whom Black women fans must labor to race-bend Black cultural specificity (read: authenticity) and that this was a detriment to creator and writer Shonda Rhimes's work (Warner 2015b, 764). Kimberly Kennedy notes that tags purposely serve as both information organization system and "as a vehicle for personal commentary and communication with other users" (2024, ¶ 3.3). The underlying assumptions behind "race-neutral" and "colorblind casting" terminology, at the time, frustrated me as a budding scholar, and I wrote my stream-of-consciousness response in the tags of my post.

[4.3] Using Tumblr's hashtags can be strategically and politically deployed, particularly if offering criticism. When a post is reblogged, the tags on the post are wiped clean so that the reblogger can add their own, which contextualizes a user's response to the original poster. At the time, I was thinking through modalities and insufficiencies of the representational rubric, which was a chief concern of the PhD dissertation I began in 2015. Warner's argument was simply representative of a larger problematic framework, and my tags were a response to arguments that fix Black femininity in familiar but limited tropes, the absence of which deems null the character's racial specificity. It is a flawed argument elegantly interrogated by Tara-Lynn Pixley (2015), whose work, coincidentally, appears alongside a different article of Warner's (2015a) in The Black Scholar Journal dedicated to Scandal earlier in 2015. Unbeknownst to me, Warner was following my blog and my Twitter account. She read my post and tags. On Twitter, she thanked me for spreading the word about her article and took my criticism, though she remained firm in her argument about the creator, Rhimes, having a history of colorblind approach to her work. We fundamentally disagreed on the degree of its insidiousness, but it was without rancor, and we went about our day.

[4.4] My Tumblr post, however, took on a life of its own, garnering a fair amount of engagement within the fandom, resulting in multiple streams of discourse. Some responses were about the content of my original post. In contrast, others responded to my tags about the diversity of Black femininity, going as far as copying and pasting them in their responses for all to read (https://thefandomdropout.tumblr.com/post/131467687351/verbena99-katrinapavela-you-guys-i-cackled-and). Other Black women fans expressed a distrust of academics who write about Black fan communities, as in this exchange on the post:

[4.5] It reads like an indictment and likens the fandom to a group of bored teenage girls with nothing better to do than sitting around living vicariously through actors' characters. That this is just very specific to "Terrys" only and that other fandoms don't do the same, which wouldn't be as insulting if they weren't titled "Black female fandom." (ctron164)

Black women root for all sorts of characters, not just other black women. This is why we need our own academics on the subject, lest THEY make it into yet another anomaly/curiosity to be poked, prodded, derided, and ultimately killed. (baronessvondengler)

The fucked-up thing is the woman saying [sic] is BLACK like us. (ctron164)

Well, you know how that goes. Some of these ppl will say anything to be accepted. Sadly, it never pays to sell out your own. (baronessvondengler)

[4.6] These comments reflect the wider context of research in Black fandoms, questioning who is allowed to do it and how they are allowed to characterize the fans. Notable here is that these reactions are based on the combination of the excerpt of Warner's argument discussing shipping real-life actors and the context of Black women's fandoms. It is not based on a reading of Warner's actual piece. This defensiveness is fair, as fan studies has, in the past, had a wave of pathologizing analysis about fan relationships with their love object. While far from Warner's humanizing argument, these women had their defensive hackles raised based on partial information and (understandable) insecurity. The reactions above demonstrate the ways in which Warner (perhaps, ironically, because of her nonethnic name) is presumed to be a white (or race-neutral) researcher, thus solidifying the belief that her argument sees Black women fans as anthropological curiosities. Because I had not explicitly noted Warner's race as Black in my post, she was assumed to be white and thus suspicious. When the assumption about Warner's race was corrected as Black, thus making her "like us," baronessvondengler reaffirms her position about the researcher by casting Warner as a race traitor who gains white acceptance through pathologizing her "own" people. For that fan, no number of qualifiers about Warner as a Black woman researcher could correct an impression she had already confirmed. Perhaps this logic psychically protects baronessvondengler's fan production from judgment.

[4.7] Freedomisasecret read Warner's entire piece and had written up her reflections in a since deleted post: "I actually don't think it was strictly set up as a 'fandom as pathology' argument which annoys me to no end—but more of a call to acknowledge that processes of identification are a part of fannish behavior, and they always implicate difference" (see BCB's post). She dispels the problematic pathology argument but reaffirms Warner's argument that blackness is identified in differences and ones that are both particular and somehow universal to Black women. I think it is a stance that leans too closely into essentialization, claiming difference as a stand-in for authenticity.

[4.8] BCB had also read the full Warner piece and came back with a lengthy treatise directed at me, defending Warner's work. I presume she saw my tagged comments about Black femininity and took personal offense on behalf of Warner, with whom she was friendly and ideologically aligned. BCB's main bugbear concerned Black women fans having to do ideological work to fill in gaps in Olivia's blackness (https://babycakesbriauna.tumblr.com/post/131668674331/katrinapavelababycakesbriauna), which Warner (2015b) highlighted. Pope's fictional Black femininity fails some fans' authenticity test and comes to signify a failure against Black women by the series creator and head writer, Shonda Rhimes. Furthermore, protesting the unacceptability of this failure means treating Rhimes, and those who fail to sufficiently criticize her writing, with often virtue-signaling derision. For these fans, Rhimes's identity as a Black (presumed heterosexual) woman is inextricably tied to fan expectations and disappointments in Pope. For BCB and others, katrinapavela's blog disseminated Rhimes's viewpoint, which BCB had come to reject. Any of my racial and gendered ideologies deemed similar (even if not) to Rhimes meant I needed to be rejected publicly as a BNF and perceived avatar for Rhimes.

[4.9] BCB, though she had admitted in her reply to no longer following the show closely, agreed with Warner's argument that Pope lacked racial specificity and that Rhimes engineered this to appeal to a white audience. It is notable here that BCB's assertion is not dissimilar to baronessvondengler, quoted above, who accused Warner of the same thing by studying Black women fans of Scandal. Both Rhimes and Warner are accused of being racial shills, even as they are coming from different ends of the ideological blackness spectrum. Moreover, BCB wrote that given all the critical reviews of the show and academic articles, katrinapavela should have "shifted your [my] views" by this point. She urges katrinapavela to adopt a stance more closely aligned with her evolved position. BCB's standpoint on racial identity in Scandal had changed since 2013, when she was commenting on katrinapavela's posts, race-bending Fitz, and imagining him oiling Olivia's "scalp with olive oil" (http://babycakesbriauna.tumblr.com/post/49949623886/katrinapavela babycakesbriauna). By 2015, Pope's blackness was so nonspecific for BCB that she could have been played by "a white man, and nothing about her characterization would change." This view echoes Warner's (2015b) work on Shondaland's (Rhimes's production company) colorblind casting practices.

[4.10] BCB compares Pope's inauthentic blackness with other "Black on purpose" characters—Empire's (2015–20) Cookie and How to Get Away with Murder's (2014–20) Analise Keating (note 1)—for whom Pope and Scandal paved the way, but was subsequently judged to be lacking. BCB leaves unaddressed the difference that class and environmental upbringing have on these characters' blackness—all information given by those shows. Pope's lack of imagined limitations as a Black woman is not a flaw in characterization but Rhimes's deliberate attempt at having the character appropriate white male privilege for herself, not be a white male (which is farcical). It is a perspective Black writer Zahir McGhee writes into episode 5.4 "Dog Whistle Politics," which aired two weeks before this fantagonism. In the episode, a television program about Pope is aired, and the presenter notes, "He [Eli Pope] once told a colleague that he was on a quest to do the impossible…raise an African American girl who felt fully entitled to own the world as much as any white man." That entitlement to operate with one's full humanity in the world is not the same as wanting to embody a white man. Just as racial stereotypes about Black people allow others a false sense of knowing, familiar and unifying tropes of blackness provide a false notion of its fixity. Therefore, witnessing an attempt at appropriating white male privilege ("the impossible," as McGhee notes) can invoke racial insecurity or dissatisfaction in some viewers, allowing them to feel unmoored from blackness as they know it or expect it to look like. As someone who grew up with both African American and Jamaican forms of ethnic blackness, at no point did Olivia Pope feel (to me) like a "white man," as BCB notes, or anything other than the Black woman she is. That reading, though different from BCB's, should count for something.

5. Troubling the outsider within

[5.1] As a veteran of Scandal's Tumblr fandom, I knew a lack of response to BCB would be interpreted as a moral and intellectual win for her. A lack of response typically means one has been sufficiently embarrassed into silence by the shade thrown at them. In other words, I had not sent for BCB, but she came for me publicly. Through the overwhelming anxiety and sleeplessness that night, accusations and would-be responses infesting my mind like bedbugs, I knew I would have to respond. My ego was hurt, and as katrinapavela, I had a reputation to protect. This interaction was public, and I had been dragged into an arena where I was expected to give my own performance as part of the entertainment. Moreover, I just disagreed with BCB on several points and wanted it known. I wrote a response a day later, conceding some points, presenting my own evidence, and pointing out BCB's inconsistent arguments (https://katrinapavela.tumblr.com/post/131616245704/babycakesbriauna katrinapavela). She wrote back (https://babycakesbriauna.tumblr.com/post/131668674331/katrinapavelababycakesbriauna), but I did not respond. I could not reconcile BCB's insistence that "the conversation [about Black femininity] needs to happen" with the attitude of the response, the latter indicating that the conversation was open only to one perspective on the lived experience of Black femininity (hers). Understanding and disagreement coexist. Unlike BCB, who had soured on the show and stopped watching full episodes, my fan production did not center upon disaffection for Pope's Black femininity. My original post and the back and forth with BCB received replies well into 2016. The thread fell into a fruitful discourse that did not require or entice my participation. My complaints about the show lay elsewhere and I would only discuss those with fans who knew how to hold in dynamic tension their delight as well as their dejection.

[5.2] Attempts by some fans within a fandom to enforce rules or promote allowable perspectives and behaviors while denouncing disfavored ones is known as fandom regulation. This policing can also be taken up by fans toward celebrities (Busse 2013; Scott 2017) or by fans toward each other, particularly those deemed "unruly" (Zubernis and Larsen 2013; Philips 2017). Mel Stanfill notes that fan policing produces boundaries, which in themselves are not intrinsically good or bad. The need to produce these boundaries arises from "internalized stereotypes about bad fans and the need to define oneself as appropriate" (quoted in Jones 2018, 265). An intersectional extrapolation of this concept would mean some fans attempt to police the boundaries of Black women's behavior and its permissible translations on screen. Because fans do not have the power to produce the media product itself, this power is exercised within fan spaces where the show is parsed, praised, and panned. I see boundaries that attempt to protect fans' emotional constitution (e.g., calling out intrafandom denigration or threats toward other fans) as worthwhile. However, ideological boundaries around race and gender should be made more elastic and malleable in parts.

[5.3] These debates about Black femininity are not intellectual masturbation; they are real and consequential to Black women's lives. Based on several experiences, including the one above, I began thinking about the racial logics that light the flames of fantagonism. Secondly, as I observed ideological cliques developing in the Scandal fandom, I began thinking of how communities cohere around mutual disaffection for the same media object they once loved. Based on the narrative and analysis in the previous section, I discuss intersectionality and authenticity, cultural taste hierarchies, and fandom as a spectrum that includes antifandom and fantagonism.

6. Black women have hierarchies, too: Taste, influence, and intersectional hateration

[6.1] I consider how the boundaries around racial logics become entangled with intersectionality and hierarchies of distinction (class, ideology, morality, etc.), particularly social distance from that which is deemed coarse, low, or other (Bourdieu 1984). Pierre Bourdieu notes how taste hierarchies are used as the basis for bonding and creating social distinctions. Racializing Bourdieu, I posit that, sometimes, Black women combine taste with modalities of intersectionality to create hierarchies of distinction for and among ourselves. Warner writes that "producing content is a necessary act of agency for women of color, who strive for visibility in a landscape that favors a more normative (read: white) fan identity and that often dismisses and diminishes the desires of its diverse body to see themselves equally represented not only on screen but in the fan community at large" (2015b, 34). The intersectionality Warner describes is a core part of what shapes the relationship between Black fans and media and the relationships between Black fans themselves. However, these desires are not always lofty or politically aspirational. They are sometimes petty, emotional, or based in opposition, just as tastes can also hinge on disaffections as much as our affections.

[6.2] A BNF is a fan who has gained a considerable amount of recognition within a fan community (Hills 2002). The BNF's standing has usually been achieved through "hierarchies of knowledge, fandom level/quality [of content produced], access, leaders, venue" (Jones 2018, 258). Important to note is that BNFs are not self-designated but fan-designated. That designation is not static and can change based on any number of factors. Though I did not interact with the cast or producers, some eventually viewed me as having power in the fandom. Sometimes, fans would invoke me to settle tensions, recruit me to a side of a disagreement, or speak up about an injustice in the fandom. In some ways, BCB's public callout of my politics had much to do with the perception of me as a BNF. There was online social currency and clout at stake in positioning herself as a Black intellectual challenge to katrinapavela. Indeed, my ego wanted to defend the standing I had gained in the fandom (though that standing was not always positively charged). By contrast, crimesceneamy's vulgar callout, based on my antifandom for Jake Ballard, did not threaten me in the least (https://katrinapavela.tumblr.com/post/47479675099/haters-gonna-hate-a-lesson-in-dyingof-laughter). In any fandom, boundaries and enforcement usually reflect two broad categories: power and perception. Where perception is concerned, this is based on an outside gaze of the fandom as a reflection of the fan object itself. In Dana Chatman's (2017) discussion about Black Twitter's watching of Scandal by fans and antifans, the latter deride the former for deriving pleasure from watching a problematic show (2017). That would make those hate-watching antifans unproblematic by contrast, thus reifying their moral Black ideological superiority over those with an affinity for the show. BCB symbolically unraveled the illusion of any power I thought I had and the precarious liminality of my position as an outsider-within in the Scandal fandom.

[6.3] Collins notes that "while a Black women's standpoint exists, its contours may not be clear to Black women themselves. Therefore, one role for Black female intellectuals is to produce facts and theories about the Black female experience that will clarify a Black woman's standpoint for Black women" (1986, S16). Collins is not suggesting that Black women's standpoint is monolithic, but it is important to note that the outsider-within positionality of the acafan in fandoms reveals various subjective tastes and hierarchies in which we knowingly and unknowingly participate. Elizabethsmediatedlife was a communications researcher and Scandal fan who had been active in both worlds since as far back as 2013. I learned of Warner's Cupcakes chapter from elizabethsmediatedlife (note 2). I bring this up as an example of how researchers frequently position themselves in these liminal spaces and that hostility is fostered by disagreement, specifically around matters of identity. As Scandal's plots became darker and Pope shifted in that direction, the greater grew the divergence within the fandom.

[6.4] Black women's relationship with each other in fan communities is not all based in solidarity from a race and gendered perspective. I have explored that solidarity in other works where Black women interrogate Black patriarchy, media racism, and Pope's sexuality (Pow 2021). We contain multitudes of divergences and culturally specific tastes, even within blackness. The exchange with BCB left me (at the time) with a sense that I (and others who agreed with me) had been doing Black womanhood wrong. Laurie Schulze, Anne Barton White, and Jane D. Brown found that antipathy on the part of some fans toward others was grounded in the perception of some fans as a "low-Other" (1993, 31). That one can be othered within a group of Black women for one's view of Black womanhood speaks to both the diversity of situated knowledge and lived experience in the group. Additionally, it highlights the diversity of age, political orientations, and social location (both geographically and economically). It is worth examining the more complex contours of these relationships, including how disaffection creates division as well as opportunities for social bonding.

[6.5] Gray (2019) says that antifans can go beyond finding opinions objectionable, finding the very identity of other fans as a basis for rejection. Though not explicitly referring to race, it is helpful for thinking of its use in Black women's fandoms, where opinions are often bound up in epistemologies of lived experiences, which can differ. Thus, when one's situated knowledge is rejected, it is understandable to feel that the self is also rejected. In Martin's (2019) study of Black women antifans of Tyler Perry's films, interviewee Danielle expresses an antipathy to themes in Tyler Perry's films. She owes this to the rejection she feels when watching them. To her, Perry's themes of Black respectability make her feel not "good enough" (171). Because Danielle did not see her lifestyle brand as a Black woman reflected in Perry's films, she rejected his work as a defense against the condemnation she felt. Perhaps BCB's changed standpoint reflected a sense of becoming unmoored from Pope's Black femininity. This turning away, notes bell hooks (1992), is a form of protest. But this was not a literal turning away but an ideological and emotional one due to feeling othered in their Black womanness. Danielle and others Martin interviewed continued to reluctantly consume Perry's films out of a sense of economic duty and social ties.

[6.6] Perry's films were also dismissed by the women in Martin's study based on lack of sophistication and a plethora of "coonery" (Black buffoonery), which they see as perpetuating negative stereotypes. While the racial history of the "coon" has been a tool of white supremacy (Bogle 1973), buffoonery in work produced by Black creators for the consumption of Black audiences is not the same thing, nor a necessary cause for racial shame. The women Martin (2019) interviewed and those represented in my research lend racial contours to Bourdieu's (1984) notion of class and social distinction. Martin's work and this piece demonstrate how taste and social bonding converge with Black cultural media around complex fan practices.

7. Fandom as a spectrum: Disaffection and social bonding

[7.1] John Fiske (1989) notes that fans use media to explicitly interpret the world around them, reproducing parts they like the most. This deeply affective process applies even to the antifan, who does the opposite: reproduce parts of the world they dislike the most (Johnson 2017). This further complicates the idea of fantagonism predicated on intersectionality. The disparagement of Scandal's politics around Black womanhood may be the point. As I see it, the antifans' love language is expressed most authentically through biting criticism and denigration, be it of clothing, characters, or storylines. The virtue signaling taking place is for disaffected fans who either never liked the show or had since fallen out with the show due to severed expectations. Affective bonds begin to form on a foundation of hypercriticality, which, if breached, would sever those bonds. Performing hypercritical discourse of the show is the stickiness that reinforces both a sense of communalism and an authentication of "true" Black womanhood.

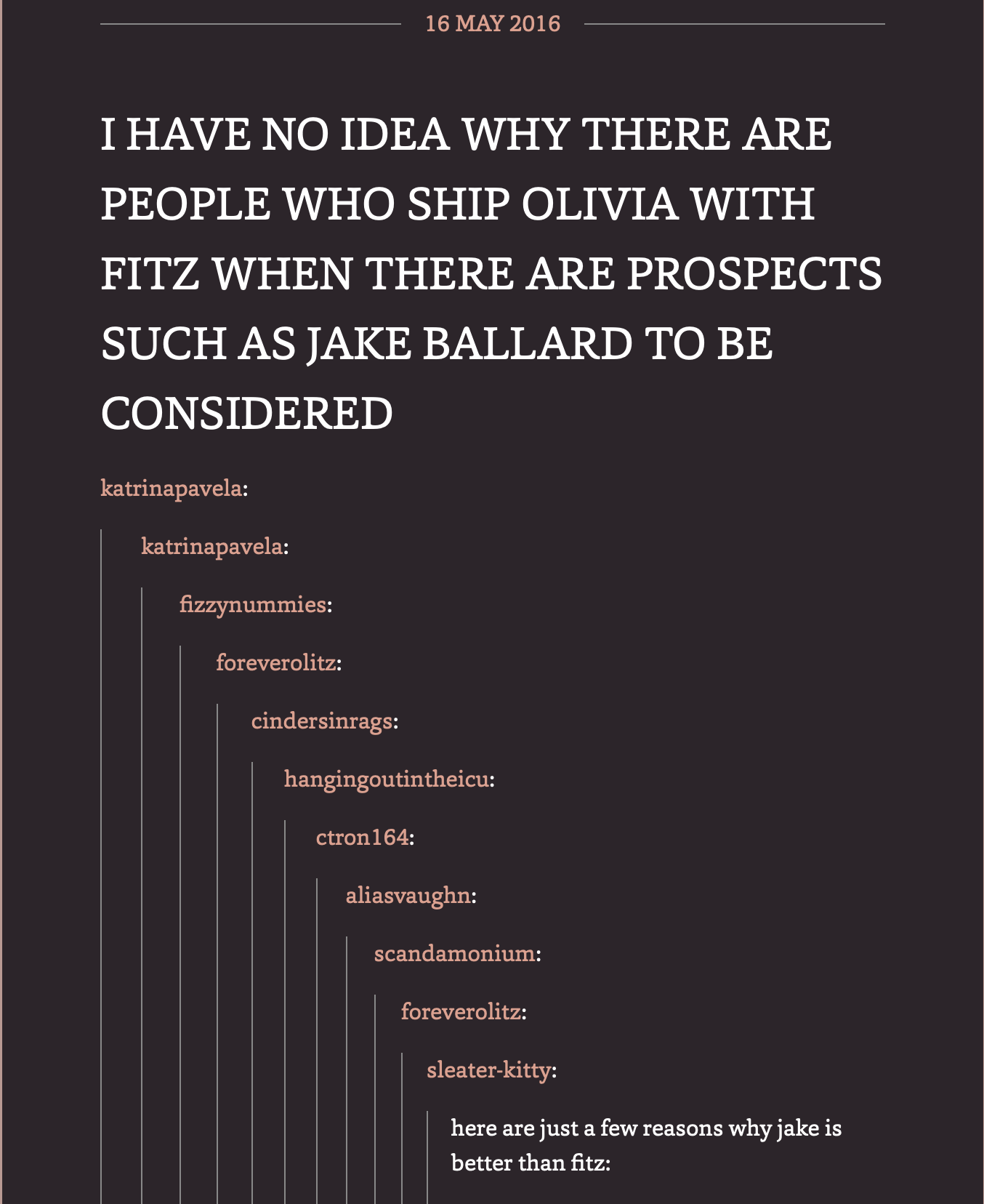

[7.2] One of the tacit rules in some Tumblr fandoms is being mindful of tagging one's hate or anti opinions. The presumption is that default fan production should reflect an affinity for the fan object, even in jest. Content that is specifically antagonistic or hypercritical is encouraged to be tagged with suffixes like "hate," "trash," or similarly derisive terms. I did not always do this, especially regarding Jake Ballard on Scandal. I was part of a community of hate with other Black women, but I did not see it that way. Our performative antifandom for Jake Ballard, an interloper in the central ship of Olivia and Fitz, was also a way of expressing love for the couple. The more we hated Ballard, the more we loved Olitz and reinforced our bonds with each other (figure 1). This social performance of hate, as Bethan Jones (2018) notes, serves a social function that coheres like-minded antifans in addition to reifying their imagined superiority of taste. I saw myself as righteous, insightful, and funny. Because Ballard is a TV character, this allowed me to see my subposts and direct posts as victimless entertainment. The Jake Ballard fandom felt very differently.

Figure 1. Olitz fandom tag-teams antifan hate for Jake Ballard (Goldenseal 2016).

[7.3] Social bonding depends on performance but does not have to be rooted in positive emotion or affinity. Disaffection must be performed to attract like-minded others and to provide emotional release in its expression. The Black women fans of Scandal were not only heavily engaged in the contested politics of authenticating Black womanhood but used oppositionality to form affective bonds with each other. Sara Ahmed (2004) notes that not only is emotion culturally and historically rooted, but it can also function to reinforce hierarchies. Ahmed's writing on cultural productivity of affect that is oriented in disaffection is useful for thinking through fandom as a spectrum that includes antifandom orientations, rather than as two sides of a coin. A social bonding based on disaffection (antifandom) for Tyler Perry's work (Martin 2019) provides a feeling of insiderness or social cohesion. Based upon a discourse of Black cultural products, this type of social bonding resists easy categorizing, skating between affinity, apathy, and antipathy. All of it is part of Black communal bonding, long established in physical spaces (Harris-Lacewell 2010; Wanzo 2015) but now extending into online ones.

[7.4] The spectrum of fandom and fan orientations can be grounded in affinity, disaffinity, floating between those poles, or gathering from both. Fan and antifan become points on a spectrum, the fulcrum for which is the media (or other) object. The gauge of the spectrum moves with the fan's orientation to (or relationship with) the object. If the material is required to spark connectivity or provocation, or to cohere the group, then the orientation (positive or negative) toward the material matters less than its social stickiness. Be it Tyler Perry's oeuvre or Shonda Rhimes's penchant for interracial relationships in her shows, if a fan group's cohesion hinges on shared derision of a piece of media, the relationship to that object remains important. Relationships with media objects can change from love to disappointment to disdain (often a defense against disappointment). Short of complete disengagement from the fan object, this holds true no matter where the fans travel along the spectrum between affection and disaffection. Furthermore, maintaining a disaffected relationship helps refine the identity of the fan as one who is culturally distinguished because, unlike others, they can see the deeper or harmful potentialities of the media object. Or, to summarize Jones's reading of Ahmed (2004), disaffected fans "reinforce their positions as subcultural authorities and secure their social hierarchy" (2019, 286). Moreover, I argue that fans protect their sense of racial and feminine identities by doing so.

8. Conclusion

[8.1] The arguments presented amount to what is Black in Olivia Pope and what this says about the rest of us. Beyond our abrasive encounter, BCB and others fortified their social relationship through intellectual distinction, based on racial logics, about the authentic representation of Black womanhood. This effort is really concerned with the fight for the meaning of Black womanhood and the right to interpret that for ourselves in diverse ways. From Bobo (1988) to Kristen J. Warner (2015a) to Francesca Sobande (2017), Black women scholars have been documenting how Black women, as cultural readers and fans, participate in negotiated readings of Black-produced media texts and perform reflexive identity work, the results of which can be divergent.

[8.2] Beyond the parameters of this research, resistance to Black multiplicity can lead to fantagonisms or intraracial debates about authenticating identity—both regarding discussions of the narrative and subject matter taken up by fictional narratives. Issues concerning identity are not intellectual masturbation fodder; they matter. "Black" as a category of identity within fan studies is insufficient without intersectionality, which highlights all the facets of the lived experience. This article intended to convey through data and personal experience how Black women fans deploy intraracial logics, social hierarchies of bonding, and fan disaffection in complex forms. Furthermore, those logics can promote insiderness and outsiderness, vulnerability, and social tension within Black identity formations. Such is the dynamic experience of being a Black woman, where intersectionality is an axiomatic part of participating in media fandoms.