1. Introduction

[1.1] One might say that there have been antifans of Shakespeare as long as there have been fans of Shakespeare. Thomas Nashe may have rejoiced at the "tens of thousands" who wept at the death of Lord Talbot in Henry VI, Part 1 (1592, sigs. Hv–H2r), but the very same year saw Robert Greene denigrate the man from Stratford-upon-Avon as "an upstart crow beautified with our feathers," almost but not quite accusing him of plagiarism (1592, sig. Fr). In 1776, the same year that David Garrick, the man who built a literal temple to Shakespeare next to his house, retired from the theatre, Voltaire characterized the playwright's body of work as an "enormous dunghill" containing a "few pearls" (1964, 10). In a review of Cymbeline for The Saturday Review, George Bernard Shaw wrote that he despised Shakespeare so much that "it would positively be a relief to me to dig him up and throw stones at him" ([1896] 1989, 50). Not long after this—and much to Shaw's delight—Leo Tolstoy recalled feeling "an irresistible repulsion and tedium" upon first reading Shakespeare, describing the playwright as neither "a great genius" nor "even […] an average author" who is nevertheless praised for his "non-existent merits" (1907, 7). More recently and succinctly, National Public Radio host Ira Glass tweeted his epiphany following a 2014 performance of King Lear: "No stakes, not relatable. I think I'm realizing: Shakespeare sucks" (https://twitter.com/iraglass/status/493609943879397376?lang=en).

[1.2] Melissa Click later opened her edited collection on antifandom with a seemingly simple question and series of answers: "What is the opposite of fandom? Disinterest. Dislike. Disgust. Hate. Antifandom" (2019, 1). Four years later, in 2023, in the midst of major strikes against the entertainment industry, the terms antifan and antifandom had themselves become a source of contention. Within her introduction, Click identified "two issues related to the expression of antifandom in convergence culture" that stood out to her, namely the "divisive potential of the critical or 'snarky' stances some digital audiences perform online, and the privileges convergence culture offers to those groups with greater online visibility" (9). Both of these issues have since bled into mainstream discourse, particularly in the Anglo-American sphere.

[1.3] One might wonder how one gets from antifandom to Shakespeare. As Suzanne Scott observes, "transmedia stories disintegrate the author figure, as artists in different media collaboratively create the transmedia texts, but in order to reassure audiences that someone is overseeing the transmedia text's expansion and creating meaningful connections between texts, the author must ultimately be restored and their significance reaffirmed" (2012, 43). Although her study of this unified author figure focuses on contemporary directors, writers, and showrunners, Scott's framework can nonetheless be applied—with some caveats—to someone like William Shakespeare, whose cultural significance extends far beyond the plays and poetry he produced during his lifetime.

[1.4] Our approach envisions two intertwined and overlapping threads of antifan engagement with Shakespeare: (1) external antifandom, or trolling, that challenges the quality of his work or the perception of its cultural and intellectual value, and (2) internal antifandom, or gatekeeping, couched as a defense of Shakespeare against perceived threats posed by other Shakespeareans. Both varieties of antifandom can either—or simultaneously—do important critical work or playfully interrogate Shakespeare and his cultural status, affirming the importance of antifan discourse in resisting and critically reading hegemonic culture. Problems arise, however, when these debates embrace what Emma A. Jane characterizes as "e-bile," or online discourses that express misogynistic, racist, homophobic, ableist, or other bigoted tropes in the service of their arguments (2019, 42–44). Such discourses are evident in both external and internal Shakespeare antifandom, and they are not limited to digital or anonymous platforms.

[1.5] Expressions of Shakespeare antifandom commonly revolve around themes of elitism, whether in attacking Shakespeare or defending him, paradoxically enshrining the antifan as a more discerning audience that is not as easily duped as their fannish counterpart. Writing across two centuries, Voltaire, Tolstoy, and Shaw are united in their opposition not just to Shakespeare but to those who are "inoculated with Shakespeare worship," according to Tolstoy (1907, 34). Shaw in particular spent his entire career mocking uncritical "Shakespeare fanciers" who were so blinded by their idolatry that they could not see even the most obvious faults in his work ([1900] 1989, 206). The tragedy for these critics, it seems, is that they are in the minority and are forced to suffer the "Shakespeare fanciers" who form the majority. The elitism of this perspective is bolstered by other cases of antifans who ridicule Shakespeare fandom as performative intellectualism: "You just like to say 'Shakespeare' at people, because whoring his name out makes people think, for some reason, that your brain is worth something," writes Reddit user FuckTheBard (https://www.reddit.com/r/TellReddit/comments/r0x7t/fuck_shakespeare_that_piece_of_shit_asshole_im/). In addition to these external antifans, internal antifans have employed similar logic to defend Shakespeare against those audiences deemed too dim or ideologically misguided to properly appreciate the man from Stratford-upon-Avon. Arguably one of Shakespeare's most prolific internal antifans, the late Harold Bloom sought to defend Shakespeare against "the anti-elitist swamp of Cultural Studies" (1998, 17). If anyone is wondering who gets Shakespeare wrong, Bloom is happy to remind us: "Marxists, multiculturalists, feminists, nouveau historicists—the usual suspects" (662). Nor did this strain of internal antifandom die with Bloom in 2019: it can be found in every complaint about "woke" or "politically correct" Shakespeare that crops up in the news.

[1.6] Debates regarding the value or importance of Shakespeare bear striking similarities to debates within and about fandom and fan objects, with external antifandom expressed by focusing on the fans themselves, such as in FuckTheBard's rejection of Shakespeare fans as pretentious snobs who just want to sound smart, or on the fan object itself as a bad object unworthy of fandom because of its perceived faults. By contrast, Shakespeare's internal antifans fall into a familiar rhetoric articulated in different ways: you just don't get it, but maybe you're not clever enough to get it. Undoubtedly, both sides of these debates do more than simply antagonize and troll, raising salient points regarding pedagogical approaches to Shakespeare specifically and canonicity more generally. The anti-elitism expressed by FuckTheBard—while not explicitly engaging with fandom or fans as a concept or identity—nonetheless articulates familiar tropes about fandom. Implicit in this user's post is the assumption that a fan object should spark a sense of affective pleasure or joy, spontaneously felt, which, from their perspective, is inaccessible to new or even avid readers, with pleasure reserved for a select few: "If you enjoy Shakesperian [sic] theatre, then I must assume that you are also a historian. […] Chances are, however, that you are NOT a linguist, a historian, a literary conniosseur [sic], or even bright enough to understand some of the basic irony sprinkled through[ou]t Shakespeare's works." Because Shakespeare is only truly accessible to the linguist and the historian, anyone else who says they enjoy or love Shakespeare must be pretending since they do not possess the requisite keys for unlocking pleasure. This user's response is fascinating for a number of reasons, primarily because it expresses a kind of modified gatekeeping.

[1.7] As Suzanne Scott and others have emphasized, this "boundary policing" of the perceived authentic fandom has historically prioritized "overwhelmingly, white, cishet men who tend to decry the loss of fandom's subcultural authenticity" at the expense of fans who are "othered" by their gender, racial, or sexual identity (2019, 4). We can see this clearly in Bloom's perspective, which aims to establish parameters for who he regards as "real" readers of Shakespeare, excluding any who do not possess the right amount or types of knowledge (1998). However, whereas gatekeeping in fandom normally excludes others from the real fans, the us of fandom, FuckTheBard employs a similar exclusionary logic, establishing the us as existing outside the fandom rather than within, an us that also includes inauthentic, self-deluding fake fans, comparing them to "a monkey remembering which shapes represent which actions they should make in exchange for a treat. You remember some smart words that someone said at you once, you are rewarded with the treat of people's positive opinion! Good job, monkey! Enjoy your cookie." The user thus positions themselves as both discerning and self-aware, smart enough to understand the parameters for inclusion in the Shakespeare fandom but secure in their knowledge that they themselves do not meet the criteria, nor do they want to. The authentic Shakespeare fan, however, remains a shadowy figure, isolated perhaps by their specialist knowledge of history and literature, unable to hold a meaningful conversation with the monkeys outside the gate—and not all that different from Shaw's sense of himself in relation to Shakespeare.

[1.8] Equally compelling are the expressions of Shakespearean antifandom that challenge canonicity, articulating debates about the value of reading and studying literature and thus the necessity of studying Shakespeare. In a BuzzFeed article ostensibly commemorating Shakespeare's 450th birthday in 2014, Krystie Lee Yandoli wrote "I hate Shakespeare," in no small part because of his embodiment of outdated ideals regarding gender. She elaborates:

[1.9] If I don't like reading modern stories and authors that perpetuate sexist ideals about gender, love, and marriage, why should I make an exception for Shakespeare? […] The dominant narrative is, more often than not, determined by society's elite. I'd rather not put an old, rich, white man from regal Britain and his antiquated ideologies about society on a pedestal. In part, he's as influential and significant as he is because of the other old white men in power who decided he would be, and who made those decisions as to which literature gets canonized. (Yandoli 2014)

[1.10] By contrast, a Reddit thread devoted to a 2021 New York Post article laments the misguided encroachment of what the users termed Social Justice Warriors into sacred Shakespearean territory. "I wouldn't be as mad about this kind of stuff if there were adequate replacements […] thing is there isn't any. Not with Shakespeare. What's also lovely is that these propositions are often experimented in lower class schools," wrote one user. "If your main purpose in teaching is to combat sexism and give voice to marginalized populations, maybe you should be teaching a social science," wrote another (https://www.reddit.com/r/shakespeare/comments/lo7atl/some_teachers_ditching_shakespeare/). Setting aside the offensive suggestion that socially conscious pedagogy belongs in "lower class schools" or that it is irrelevant to the discipline of literary criticism, the various strands of these debates over Shakespeare offer valuable and critical insight into how canon is formed, on what grounds, and on the basis of whose authority. Viewed through the lens of fandom and gatekeeping, all of these debates establish the parameters for inclusion in—and exclusion from—a fandom and reinscribe stereotypical binary notions of who fandom is for, articulated either by affirmation or opposition. In short, for these antifans, Shakespeare belongs to straight, white, middle- or upper-class men, either because, for example, feminists should hate him or because feminists lack the requisite perspective and objectivity to properly appreciate him.

[1.11] Many of these varieties of Shakespeare antifandom, however, situate Shakespeare as an author encountered almost exclusively—at least at first—in an educational setting, making him inextricably linked to notions of cultural hegemony and didacticism. That is, they assume that no one comes to Shakespeare spontaneously or through, say, the infectious enthusiasm of other fans. It seems a foregone conclusion that Shakespeare cannot spark the joy and pleasure that other objects of fandom do. Rather, Shakespeare is work, and as such, expressions of Shakespeare antifandom are often articulated in terms of labor. What is the value of Shakespeare? Is the work worth it? What can or should I expect as compensation for this intellectual labor? What am I paying for when I take a course that requires Shakespeare? As such, Shakespeare fan and Shakespeare scholar or Shakespeare student are imagined as interchangeable or synonymous identities. Without a doubt, these questions are not irrelevant to a consideration of Shakespeare and fandom since many people do, in fact, come to Shakespeare through the school system. But the strands of antifandom predicated on this assumption negate the possibility or potential for fandom to do what it so often does, to not simply adore or worship, but to transform, resist, and reform the fan object, to critically engage with it as active, rather than passive, readers and audiences.

[1.12] This approach also falls into some of the most problematic stereotypes about fandom, borrowing from the popular image of the fan as the uncritical and obsessive devotee that Henry Jenkins and other early fan scholars wrote about, but often shedding feminizing affect in the process, replacing it with the masculine heterosexism of the fanboy. And rather than being an antisocial loser living in their parents' basement, the (white cis male) Shakespeare fan operates from a position of cultural and educational authority to—depending on your perspective—edify or indoctrinate others. This in many ways echoes the rise of the "fanboy auteur," a term introduced by Scott and expanded upon by Anastasia Salter and Mel Stanfill, who argue that "transformational fans are disproportionately women, and they rework a source text—often so that it serves perspectives originally marginalized, which makes transformation also a tactic of fans of color," while "the white men tend to cluster together as affirmational" (2020, 7).

[1.13] This is how, as Jennifer Holl observes, the "fanboy status" of someone like Joss Whedon, who directed the 2013 film adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing, is "not wielded in a pejorative sense" but rather becomes "a key narrative strand in the film's promotion and subsequent reviews as a means of establishing the primarily science fiction–oriented director's Shakespearean credibility" (2017, 111). It is perhaps coincidental that the intervening years since Whedon's film have seen justified backlash against both him and Shakespeare, albeit for different reasons, and a significant rise in antifan discourse that is more explicitly oppositional than transformational.

[1.14] The articles in this special section touch on all three of the broad categories of antifandom identified by Jonathan Gray (2019). We can see bad object antifandom writ large in the authorship controversy, where Shakespeare studies assumes that Shakespeare was the author of the works attributed to him. The anti-Stratfordians position themselves as underdogs fighting an entrenched Shakespearean hegemony, even when, as Johnathan H. Pope makes clear in his analysis of the film Anonymous and its backlash, those alleged underdogs have the wherewithal to produce high-budget Hollywood films. Disappointed antifandom may, on its surface, seem harder to find within Shakespeare studies, but nonetheless manifests in the many threads of scholarship that interrogate Shakespeare's centrality to the western canon, some of which are discussed in Jessica McCall's article questioning the universality of Shakespeare. Moving from the theoretical to the theatrical, Emer McHugh uses the Druid Theatre Company's radical adaptations of Shakespeare to explore the tension surrounding notions of authenticity in efforts to simultaneously resist and reform a canonical English author for an Irish audience. Edel Semple's contribution then turns to film and television, specifically on how two recent films and one series have positioned female characters as disappointed antifans within narratives about Shakespeare. Lastly, for antifans' antifandom, one need only look at the backlash to those disappointed Shakespeareans, the gatekeeping and harassment they face for daring to critique a sixteenth-century playwright using allegedly anachronistic frameworks. Putting, for instance, racism or sexism in the same sentence as Shakespeare's name is enough to inspire certain people to a frothing rage, even though there is ample evidence that these topics are relevant and indeed central to any twenty-first-century discussion of Shakespeare. L. Monique Pittman's analysis of the gatekeeping and policing of access to Shakespeare and his elevation as "white property" (to use Little's [2021] formulation) in the Netflix series The Crown illustrates how antifandom can promote a sense of imperial nostalgia for the whitewashed past exemplified in heritage television. Kavita Mudan Finn then uses the sonnets and the relationship between fanon and canon to interrogate how readings of Shakespeare's life—about which we know frustratingly little—reflect the evolution of ideological desires from his lifetime to the present day. The first symposium essay, by Chelsey Lush, explores the intersection between material culture, ecology, and fandom through her focus on Shakespeare's mulberry tree, reputedly planted by the playwright in Stratford-upon-Avon but cut down in the eighteenth century. Finally, David Sterling Brown powerfully reflects—through a (re)reading of James Baldwin's 1964 essay on Shakespeare—on loving, hating, and liking Shakespeare as a Black man already grappling with a world of anti-Blackness.

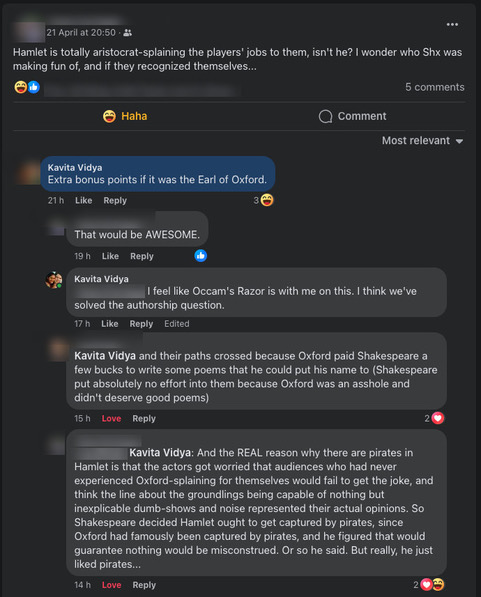

[1.15] Together, the articles in this section demonstrate that Shakespeare antifandom is as multifaceted as Shakespeare fandom. It can be playfully antagonistic or righteously serious in tone; it is ideologically diverse, to the extent that various factions of Shakespeare antifans are likely to be antifans of one another. It can be jingoistic and tribal or grounded in ideals of diversity and inclusion. It can be motivated by anger, as seen in the Reddit posts quoted above, or pleasure, as seen in figure 1 below in the exchange between several scholars on social media poking fun at scenes from Hamlet. In short, the one thing that Shakespeare antifandom is not is monolithic.

Figure 1. Exchange on social media on the topic of Shakespeare possibly making fun of someone specific in the interactions between Hamlet and the players. Reproduced with permission of the participants, some names redacted for privacy. April 23, 2024.

2. Acknowledgments

[2.1] This special section began in 2019 as a proposed book, but life and a global pandemic intervened. We (Kavita Mudan Finn and Johnathan H. Pope) are deeply grateful to our wonderful contributors, and to Mel Stanfill and the editors of Transformative Works and Cultures for giving us this space to speak to both Shakespeareans and fan studies scholars, as well as—through open access—any fan or antifan who might want to know more about this long-running and fractious fandom.