1. Introduction

[1.1] Building on societal fears stemming from biases and stereotypes, the horror genre is ripe for critical analysis. As Gray (2020) explains, American horror often targets fears about societally othered identities that deviate from what is seen as normal, or white, middle-class heterosexuality. Characters are othered when they become a source of fear, either literally turning into a monster, becoming a dehumanized antagonistic threat, or being otherwise removed from the narrative (e.g., dying). Critics note stigmatizing archetypes in horror around race, gender and sexuality, and mental illness. For instance, racialized horror tropes include Black characters dying first to establish the power of the monster, while gendered archetypes include promiscuous or sexual female characters being punished with violence. Monster arcs can mirror societal narratives about queerness, evoking fears of sex and death, while mentally ill characters are often cast as villains—like the common slasher antagonist, a human who goes on killing sprees.

[1.2] Until Dawn (Supermassive Games, 2015) is an award-winning horror video game where eight diverse teens navigate a series of supernatural and psychological mysteries. The game is built around a butterfly effect mechanic, where choices made from a first-person point of view for each character affect the final outcome of the story. As the players make choices on behalf of each of the teens, the game allows for different interpretations of the characters and story plotlines. Players can affect everything from the minutiae of the teens' relationships to major plot events like who lives and who dies.

[1.3] In addition to including several archetypal horror plotlines as red herrings, each of the eight characters who are introduced align with particular genre stereotypes: "dumb jock, arrogant rich girl, flirt, nerdy class clown, alpha male, etc." (Allison 2020, 287). The game often allows players to make choices that either lean into the stereotypes or diverge from them. For instance, Emily—an Asian American female character—can either stumble into her own demise (aligning with more passive stereotypes) or escape as an action hero on a zip line (subverting such stereotypes).

[1.4] This game is popular enough to have both critical scholarship as well as an active fandom engaging with the many possible story paths with reaction videos, fan fiction, art, and cosplays. Both critical scholarship and artifacts of fan engagement provide a context rife with possibilities for understanding how readers critically engage with texts across different mediums, modalities, and genres. We examine various ways that fans within the Until Dawn video gaming community navigate and critique aspects of the horror genre through various critical practices.

2. Critical fandom practices via live streaming, fan fiction, and cosplaying

[2.1] Readers can take up critical literacy practices to both deconstruct the impact of texts othering characters and reimagine them in more socially just ways (Lindhé 2021; Thomas 2019). Critical game literacies—including ways fans interpret, respond to, and reimagine video game texts (Coopilton 2022)—are especially important for reading horror texts, which often reinforce stereotypes or biases. This section reviews research on critical practices across live streaming, fan fiction, and cosplay contexts as we trace connected trajectories in critical practices across all three types of fan engagements.

[2.2] Live streaming, an activity where gamers broadcast their playthrough of a game while viewers watch and interact, allows players to share commentaries; explain their choices; and invite audience responses or participation, with opportunities for critical responses to the game itself. For example, studies show gamers narrating ethical decisions about interacting with monstrous characters (Piittinen 2018), young Black video gamers making customized Black Lives Matter designs (Cortez, McKoy, and Lizárraga 2022), and female gamers taking up critical practices to critique sexualized comments made by male characters (Nguyen 2016). Live streaming activities open space for gamers and viewers to collectively make meaning and critically engage with sociopolitical issues through commentary and gameplay choices.

[2.3] There is growing interest in how fan communities change or restory settings, characters, and storylines (Thomas 2019) through various mediums and modalities such as fan fiction and cosplay. Slash or femslash fan fiction pieces feature queer pairings of characters, which allow for fan conversations around gender and sexuality (Stanfill 2019), while Black fans have collectively reinterpreted characters as Black in fan fiction and fan art (Thomas 2019). Fans with disabilities write fan fiction that foregrounds disability narratives not present in source content, such as adding disabled characters to the Marvel worlds (Raw 2019). Some topics are more prevalently addressed in fandoms than others. For instance, the Twilight fandom often addresses gender problems through fan fiction (Eate 2015) but is less likely to address critical issues of Indigenous representation.

[2.4] Cosplay, the practice of creating and wearing costumes to embody popular characters from media and fandoms in fandom spaces, can also be leveraged toward critical ends. Cosplaying literacy practices include authoring identities through character affiliation and dismantling of stereotypes (Aljanahi and Alsheikh 2021). Cosplayers shifting between their own and their characters' identities in moment-to-moment play allows for "embodied translation" (Kirkpatrick 2019, ¶ 5.2) of source characters. For video games specifically, Lamerichs (2018) argues cosplaying blurs boundaries between the physical and the digital, affirming and amplifying affective connections to the character while "personalizing it and drawing it close" (150). This allows for the emergence of critical practices closely connected with cosplayers' own identities, inclusive of (but not limited to) disrupting harmful gender stereotypes (Mishou 2022). With respect to race, critical practices such as race-bending (cosplayers of color reinterpreting white characters) can disrupt the whiteness of mainstream media (Kirkpatrick 2019). However, miller (2020) cautions white cosplayers to attend to their potential to erase characters of color in their choice of cosplay (e.g., trends of white cosplayers embodying Katara from Avatar: The Last Airbender).

3. Considerations for interactive video games in fandoms

[3.1] Jennings (2015) highlights the importance of considering potential versus actualized textualities when playing video games. Actualized textualities refer to one person's playthrough of a game, while potential textualities acknowledge the multiplicity of experiences and interpretations of different playthroughs. Expansive analyses of video gaming experiences do not just consider one decontextualized playthrough but the multiplicities of gaming practices across contexts, communities, and materialities.

[3.2] Interactive aspects of reading video games allows for critics to speculate on the amount of narrative control afforded by the game and its literary effect. Allison (2020) argues that Until Dawn purposely limits player control. Some seemingly consequential choices (like choosing which character to kill) lead to fixed outcomes whereas missing quick-time events—a prompting to quickly press a button in a video game—can lead to significant deaths of characters. This, she says, limits conscious control of the narrative and heightens horror-related feelings of powerlessness. However, players may resist the lack of control through metagaming practices (Boluk and LeMieux 2017) that allow them to take back agency over their decision-making despite the game's design.

[3.3] Players often make sense of their proliferating experiences of video games within fandom communities. Even if a single player has not played every branch of the game, players can connect online to expand their understandings of these texts: "Online communities weave together the partial knowledge of many players to start crafting the tapestry that will help to explain the game's vast and contorted expanse" (Jennings 2018, 168). Examinations of critical practices in such games are therefore complex and communal, as players with various identities and concerns share playthroughs and resources around many different potential textualities.

4. Review of critical response to Until Dawn

[4.1] As a popular award-winning game, Until Dawn has been analyzed by many scholars and critics in regard to issues of gender and sexuality, mental illness, and race and cultural appropriation. Across the literature, critics suggest that female characters are devalued through dialogue (McCullough 2021) and that the game reifies certain horror archetypes of "white male dominance, sexual prowess, and protector imagery" (Waldie 2018b, 72) through its characterization and design choices as well as mechanics (such as access to weapons). Fawcett (2020) also notes how one of the characters (Jess) is punished after a speech about her comfort with sex by immediate physical violence from a monster, playing into horror archetypes around sexual conservatism for women. Additionally, critics say the game draws from dehumanizing stereotypes of mental trauma and illness (Waldie 2018a). Often referencing his lack of medication, the game characterizes the character Josh as mentally ill, and he is one of the few main characters who can transform into a monster at the end of the game.

[4.2] Finally, critics raise issues of intersectional racialized stereotypes, such as Waldie's (2018a) observation that the only Black male character, Matt, is portrayed as an archetypal dumb jock. Several critics also argue that this game engages Indigenous cultures in appropriative ways. According to the game, the mountain where Josh's family has their cabin is sacred to the local First Nation tribe, and European miners harmed the mountain and released the wendigo spirit that curses people engaging in cannibalism into becoming monsters. The game's so-called wendigos (including miners as well as a transformed teen named Hannah) are the main antagonists. A salient mechanic of this game is that characters can preview future possible events by finding totems from this local tribe. Fawcett (2020) critiques these aspects of the game for cultural appropriation: "While the original wendigo tales stretch across cultures, communities, and time, taking on complex social signifiers, Until Dawn simplifies the wendigo to its core concept: breaking the taboo of cannibalism transforms the person into a supernatural cannibal. This simplification reduces the wendigo to a modern Western zombie" (94).

[4.3] Eddy (2020), an Indigenous live-action role-player herself, describes how appropriation of cultural elements like wendigos in fictional storytelling is both offensive and othering, leading Indigenous gamers to exit such storytelling spaces.

[4.4] These three categories (live streaming, fan fiction, and cosplay) lead us to our guiding research questions: (1) In what ways does a focal group of fans critically engage with what is positioned as the monstrous in Until Dawn? and (2) In what ways across contexts and modalities do fans take up or restory tropes in Until Dawn? Both of these questions examine horror elements of the game positioned as problematic by the literature: gender and sexuality, mental illness, and racial stereotypes/cultural appropriation.

5. Methods

[5.1] This is an immersive-participatory case study (Cuttell 2015) situated within an affinity space ethnography. Data collection for this study was approved by New York University's institutional review board (IRB) as part of an ongoing study of learning at New York Comic Con (NYCC) beginning in 2018. Affinity space ethnographies are multisited explorations of fan activities and literacy practices that stretch across "time, space, communities, modes, and tools" (Lammers, Curwood, and Magnifico 2012, 48). Developed in the field of literacy research, these methods are often multisited (Vossoughi and Gutiérrez 2014), crossing digital, in-person, and blended spaces where fans make meaning. Video game practices are expansive, and studies of affinity space practices relating to video games have crossed many contexts, ranging from various digital video gameplay spaces frequented by one player taking on different roles (Pellicone and Ahn 2018), networked digital fan fiction interactions expanding from a solo-player video game (Lammers 2016), and different group gaming activities happening in one physical space (Abrams 2012). However, little work has been done to examine video game literacy practices across gaming spaces and physical cosplay conventions, the focus of our study.

[5.2] Affinity space ethnography methodologies suggest prolonged periods of situated observation of digital practices (Androutsopoulos 2008; Lammers 2017) in order to locate and bound activities of interest. Relatedly, feminist-epistemological methodologies for studying video games call for "critical analysis of the situated play of video games," as "players are parts of the video game text" (Jennings 2018, 160). Making the researchers' engagement with video games visible through immersive participatory methodologies (Cuttell 2015) allows for reflexive meaning making with the video game text through attending to the intersectional identities of the players and how that influences their experiences and interpretations of video games as texts. The importance of situated play and situated observation for studying a video game within a fandom affinity space lends itself well to autoethnographic methods around participant-researchers' practices within a fandom community. Autoethnography "places the self within a social context" (Reed-Danahay 1997, 9) and is well suited for exploring the social complexities of networked media spaces (Thompson 2017). Thus, this particular study examines the intersections of our cosplay group and the surrounding affinity space, tracing practices across virtual gameplay contexts, digital fan fiction and social media postings, and in-person cosplay convention interactions.

[5.3] The focal group consists of four participants. Sahara, a white queer woman who identifies as mentally ill, is a video gamer, horror connoisseur, fan fiction writer, and cosplayer. She had both watched and played the game Until Dawn many times prior to the study. The other participants were not familiar with the game or the fandom. Sahara knew the game well and often used her past experiences playing and other fan resources (playthrough guides) to intentionally make choices or manipulate mechanics that followed the desires of the group for character arcs and relationships. As a longtime participant in the fandom, she also had experience participating in fan affinity spaces, including reading and writing fan fiction about the game. Karis is a white female cosplayer, fan, and academic whose research focuses on literacy practices in fandoms. Though she is an experienced role-player, she has less experience playing video games than the other participants. Jason, a white man who also identifies as mentally ill, is a longtime gamer and cosplayer but was unfamiliar with Until Dawn specifically. Finally, Lauren, an Asian American woman, is a gamer with a stated dislike of horror media but an interest in group cosplay. Taking up Gray's (2020) framework of intersectional tech, we note that in light of "the assumed white masculine norm in gaming" (15), these intersectional identities are important to attend to as the players navigate gaming and fandom communities.

[5.4] For the immersive participatory focal case, Sahara invited Karis and two other cosplayers to participate in a collective playthrough of Until Dawn to anticipate choosing characters to cosplay at NYCC 2021. From July through October 2021, the group met to watch Sahara play the game over six sessions, about eighteen hours of gameplay. As Sahara had already completed multiple playthroughs of the game, she invited the group to weigh in on what decisions they wanted to make in the game. While playing, Karis made field notes of both decision points and discussions of cosplaying choices. Below we share a description of the characteristics of the eight main teen characters in the game, including how much screen time they have on average in the game, their gender and racial characteristics, and which romance plots are possible in the game (table 1). All these factors were considered as the players decided who they would cosplay.

| Rank by active screen time (Waldie 2018b) | Gender | Race | Romance plotlines in game | |

| Mike | 1 | M | White | Jess |

| Sam | 2 | F | White | None |

| Ashley | 3 | F | White | Chris |

| Chris | 4 | M | White | Ashley |

| Emily | 5 | F | Asian | Matt |

| Matt | 6 | M | Black | Emily |

| Jess | 7 | F | White | Mike |

| Josh | 8 | M | White/Mixed | None |

Table 1. Until Dawn player character characteristics as portrayed in-game.

[5.5] In October 2021, the group worked together to construct their cosplays. See table 2 for a description of the cosplay character choices and how they related to the characters in the video game. Karis collected artifacts relating to cosplaying construction and cosplays (pictures, Snapchat screenshots). Additionally, the group collected approximately 150 minutes of both GoPro and handheld video data of NYCC encounters (October 2021), including pre- and post-NYCC group interviews with participants. Karis also collected social media artifacts posted online as well as digital fandom engagement.

| Cosplayer | Character | Event-related costume choices | Costume chapters |

| Sahara | Jess | Still dressed, no coat, covered in her own blood | Chapter 4 and later |

| Karis | Ashley | Post–saw scene, covered in blood from Josh's "death" | Chapter 4 and later |

| Jason | Chris | Pre-blood | Chapter 3 and earlier |

| Lauren | Hannah | Pre–monster transformation | Prologue |

Table 2. Cosplay choices linked with video game playthrough.

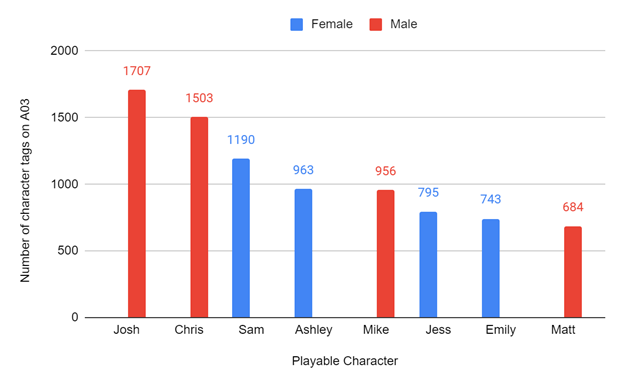

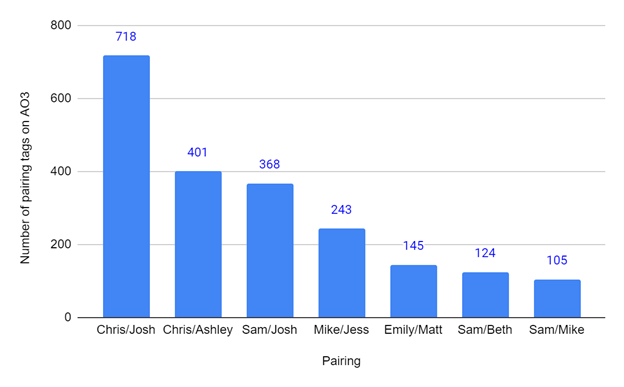

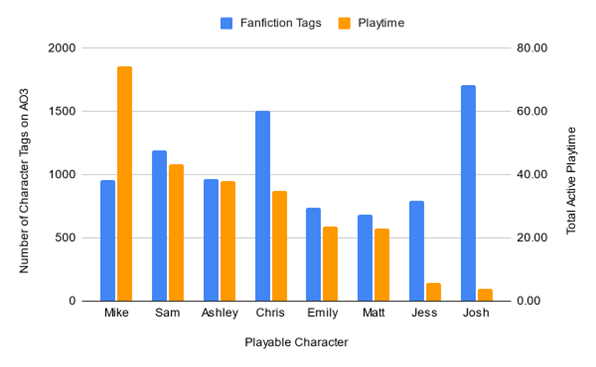

[5.6] As Sahara's experiences with the game were shaped by her experiences with the fandom community, we extended our multisited inquiry into social media spaces to further contextualize the study. Karis and Sahara traced social media engagement stemming from the cosplaying at NYCC and conducted content analyses of fan artifacts relevant to Sahara, primarily fan fiction. The team searched for fic associated with Until Dawn on Archive of Our Own (AO3). We sorted for the top fifty pieces by number of kudos (similar to likes), collecting these pieces' titles, keywords, and summaries. We divided up and (re)read these pieces until we reached a point of saturation. We also engaged with metadata from the entire corpus through the tagging systems, which are searchable through the AO3 platform, looking at popular character pairings as well as keywords across the fics (figures 1, 2, and 3).

Figure 1. Number of fics tagged per playable character on AO3 as of July 2023.

Figure 2. Number of fics tagged per relationship pairings on AO3 as of July 2023.

Figure 3. Number of fics tagged on AO3 as of July 2023 and total active playtime per playable character.

6. Analysis of connected moments of uptake for collective restorying

[6.1] In alignment with our research question, we traced how fans engage with what is positioned as the monstrous to see how they either take up or restory different aspects/tropes. We used the idea of collective restorying, where fans "deliberately contradict" (Thomas 2019, 162) authorial intent and collectively create their own interpretations or reworkings of the text. Drawing on transliteracies analytic frameworks (Stornaiuolo, Smith, and Phillips 2017), we were interested in looking for ways that these collective restorying practices emerged across the data. To make connections across critical practices occurring in different contexts (playthroughs, fan fiction, cosplaying), we used tools of uptake: "Uptake helps us trace people's sense-making practices as they signal their understandings in response to myriad things and people over time" (79). This tool surfaced how textual interpreters critically engage with the game across various contexts and sites as well as through many modalities.

[6.2] We used the categories from the literature to code the field notes of the video game live streaming, video transcripts, and the fan fiction texts for mention of or engagement with gender and sexuality, mental illness, and race or cultural appropriation (table 3). When we found a mention or engagement with a critical topic of interest connected with the video game, we traced across data sources to look for connected moments of uptake, or critical sense-making practices that signaled ongoing engagement with video game content. Looking across the data, we were interested in ways fandom texts connected to or transformed storylines from the original video game through various types of engagement (e.g., critical commentary) or restorying (e.g., playful cosplaying interactions or fan fiction stories). This helped us to see collective ways that fans deliberately addressed problematic narratives from the game or engaged with the text in a way that reimagined or transformed them.

| Critical topic | Connected examples | |

| Live streaming | Cosplaying / Fan fiction | |

| Gender and sexuality | Sahara describes to the group why she doesn't want to get "too sexy too fast" so Jess is in her underwear. | Sahara chooses to cosplay Jess in her fully clothed form. |

| Mental illness | Sahara critiques how Josh is being punished in the game for being unmedicated. | Many fan fiction tags explicitly relate to Josh's mental illness (e.g., mentions of medication or therapy). |

| Race and cultural appropriation | Karis notes that no characters in the game comment on the totem prophecies. | Few fan fictions make mention of totems or Indigenous culture. |

Table 3. Examples of uptake across data sources.

[6.3] Though we attend to intersectionality in our autoethnographic data, in some cases we did not have access to participants' identities (e.g., fanfiction writers), just their textual productions. Therefore, though we take up intersectional framings whenever we can, we join Gray (2020) in commiserating that for the purposes of this paper, we sometimes present "singular analyses around race, gender, sexuality, ability…as opposed to keeping them troubled, tangled, and whole" (22). Our discussion of fictional characters' intersectional identities are further complicated by fans' divergent readings and restorying. For instance, cosplayers may or may not make explicit their interpretations of the sexuality of the characters they embody. Fan fiction writers may not make visible their interpretations of the characters' race. The race of the character Josh in the game is never specified, though he is modeled after the American actor Rami Malek, who is of Egyptian descent. Fans may explicitly share how they are reading or restorying his character's race—or they may not. When fans surfaced these intersectional identities, we attended to them (e.g., fan fiction addressing authorship decisions relating to race, culture, and mental illness).

[6.4] Across these next sections, we show several connected trajectories of critical uptake restorying characters that were othered or dehumanized by the game, as well as some critical issues where there was more minimal uptake. Though moments of critical engagement and restorying with the video game stretched across live streaming, cosplaying, and fan fiction practices, we found that certain platforms and modalities for media engagement foregrounded particular critical issues more prevalently than others.

7. Resisting gendered archetypes of sexualization and innocence

[7.1] Here we describe how gamers/cosplayers took up critical trajectories around two of the game's female characters: Jess and Ashley. Each of these characters has the potential to align with or depart from genre stereotypes around white femininity. Jess, the flirt/slut archetype, can be stranded in her underwear and/or quickly killed once she is kidnapped by a monster early in the game, or she can be more fully clothed and escape to freedom. Ashley, the innocent archetype, has the potential to get together with her crush over the course of the game or to intentionally lock him out of a house to be killed by a monster.

[7.2] The focal players intentionally leveraged knowledge about the multiple potential storylines in a way that resisted sexualization of the character Jess. In excerpt 1 from the group's live stream, Sahara explains some of her game choices to the group in terms of respecting the character during a section in which Jess and her boyfriend, Mike, begin to engage in sexual activity.

[7.3] Sahara: If you get too sexy too fast they're already getting undressed, and then she's in her underwear when she's grabbed and that's not respectful.

Lauren: What happens if you go too far the other way?

Sahara: Then she has her jacket on and that's not gritty enough. I personally prefer if she keeps her clothes on for the rest of the game.

Lauren: Does she always get taken?

Sahara: That's a fixed event. That's not the game's best moment.

[7.4] While playing, Sahara described a careful balance she wanted to strike with her gaming choices to make sure Jess was wearing clothes when abducted in the game, to be "respectful" to her character. Sahara makes connections across several different histories of play, explaining the various storylines where her favorite character can be in her underwear or in her jacket, as opposed to keeping her clothes on without her jacket. The different outfit options for Jess are a popular conversation in fandom texts. Though YouTube videos and Reddit threads discussing Jess's different outfit choices often focus on how to undress Jess, the group chose to move away from sexualized archetypes and be more respectful toward the character despite the kidnapping "not [being] the game's best moment."

[7.5] Sahara also explained that she was specifically making choices for the group to see the particular cosplay she planned to do (figure 4). This mattered so much to her that when she accidentally killed Jess on their first playthrough, she replayed the game from the beginning to save her, as she explained: "Here's my dedication to my character. We're going to finish this chapter and then I'm going to go back and replay it on my own time—I knew I was going to accidentally kill off someone, but not the one I wanted to cosplay." We see here how Sahara's choice to cosplay Jess resisted narratives of othering, instead heightening the group's commitment to this character (Lamerichs 2018). While Allison (2020) argues that the game's branching consequences that easily lead to a character death "[work] against player mastery and control" (291), Sahara cared enough about keeping Jess alive to replay the game in its entirety to save her, forcibly rewriting Jess back into the narrative. Video games with branching options allow opportunities for players to start over as an act of resistance, making different choices in order to follow storylines that better align with their situated and critical desires.

[7.6] Situated identities in both gaming and real-life spaces informed these live streaming decisions. For instance, while deciding what to cosplay, the group discussed iconic gendered moments from the game that might be recognizable at NYCC (including female characters Jess in her underwear or Sam wearing just a towel). Sahara rejected those cosplay options, recalling real-life experiences where wearing more revealing character outfits from a show led to being sexualized in transit to cosplaying events. Cosplaying practices involve actually embodying a character in a social space, bringing with it sociopolitical consequences for players' embodied identities and experiences. Critical video gaming practices connected with imagined cosplaying futures, supporting a conscious departure from sexualized archetypes and outfits in the game in anticipation of safe cosplaying futures. We see a trajectory of critical uptake in the way that choosing to live stream a particular version of Jess in the game resists problematic gender archetypes.

Figure 4. Cosplaying Jess.

[7.7] Next we examine the character Ashley, the innocent archetype described in the game as sweet and cheerful who has a surprising path in the game where she locks her crush, Chris, outside to be eaten by a monster—a game achievement named Ashley Snaps. According to achievement statistics collected and published by the game developer, this ending is a relatively rare outcome. However, we found many fans sharing and discussing this ending in online forums and in YouTube videos, perhaps because it subverts her archetype so thoroughly. During the playthrough, Sahara shared that fans have mixed feelings about Ashley, with some fans arguing on social media that she is the worst character in the game. This character's canonical romance with Chris is often supplanted on AO3 by fans pairing Chris with Josh (figure 2), far and away the most popular ship in the fandom. However, tracing uptake across various live streamed playthroughs, this cosplay case, and social media interactions with our cosplay posts, we show ways that fans expressed critical delight in how Ashley upends her stereotypical path as the nice girl with a crush and instead chooses to allow Chris to die.

[7.8] In the live stream playthrough, the gamers guided by Sahara intentionally chose to avoid the Ashley Snaps ending to keep all the characters alive. However, after watching a clip of a playthrough of Ashley Snaps, Karis and Jason decided to stage the scene in cosplay using the convention doors as props. They shared the pictures on Tumblr in a post captioned "Using our Ashley & Chris cosplays to re-enact the path where she leaves him to die" (figure 5).

Figure 5. Re-enacting Ashley Snaps.

[7.9] Other fans of the game posted comments appreciating the cosplay and laughing at the staged scene. One user commented that Chris was "asking for it" because the cosplayer outside was not wearing a Covid-19 safety mask (while Ashley's cosplayer inside was visibly wearing one). We argue that fans took up these staged photos not as an indictment of Ashley's character as cowardly or vindictive but as funny and empowering. Note that by saying Chris was "asking for it" and pointing to the male cosplayer's lack of mask, the commenter subverts gender stereotypes. Though this turn of phrase is often used to talk about female victims inviting violence by how they acted or dressed, the comment playfully positions Chris as in the wrong for not wearing his mask. This play across gender and pandemic ethics positions Ashley as justified in her decision to lock Chris out and celebrates the trope subversion instead of punishing it.

[7.10] In addition to Karis's identification with the complexity of this character during the playthrough, connecting to feminist ways of knowing video games (Jennings 2018), the embodied nature of the cosplay (Lamerichs 2018) reproduced in the photo shoot humanizes Ashley for the viewers. This particular online community resisted gender stereotypes from the broader fandom, constructing a communal feminist rereading of this moment as funny and empowering, not vindictive or morally wrong.

8. Rehumanizing the mentally ill

[8.1] Across the various storylines, the character Josh is always othered for his mental illness. He is the only character who either has to die or literally become a monster. However, as someone identifying as mentally ill, Sahara cared about how Josh was perceived. In alignment with game mechanics that make the player rank which characters they like the most and want to save, she kept tabs on how the group felt about Josh specifically. She also cared about decision-making around Josh's storyline. When Sahara decided to replay the first three chapters to fix the storyline so that Jess lives, she also successfully high-fived Josh, a quick-time event which had been missed in the first session. She cared about Josh's relationship with his friends and wanted to make sure his character did not miss positive interactions with them. Sahara also chose to locate all optional clues relating to Josh's history of mental illness, including past treatments, medication regimen, and symptoms both prior to and after the disappearance of his sisters. Deliberate choices were made during the live streaming to explore Josh's story to the fullest extent possible within the medium and examine him more closely as a character.

[8.2] Looking across the tags for Until Dawn fan fiction for critical uptake trends, we found that many fans also cared about restorying Josh's character and story ending. Josh has the largest number of character tags, outweighing every other character despite his relatively low playtime throughout the game. As mentioned in the previous section, we found the most popular ship is Chris/Josh, a relationship which is not portrayed as romantic within the game itself. These and other stories focus on exploring and expanding Josh's romantic and platonic relationships, to a greater extent than the game itself does. Many works in the fandom also feature "canon divergence" (a tag used 227 times, the third most popular noncharacter/relationship tag) or "post-canon" (a tag used 139 times). Such stories are often centered around reframing or retelling the ending of the game, especially Josh's ending. While many stories adopt the most hopeful outcome of the game ("alternate universe—everyone lives/nobody dies" is another popular tag, used 176 times) and stay generally true to the events of such a playthrough, Josh's ending is frequently rewritten or returned to with the goal of providing him a happy ending along with the rest of the characters. His mental illness is not ignored in these stories; in fact, further popular tags include "mental health issues" (used 223 times) and "post-traumatic stress disorder" (used 130 times). Fans want to rehumanize him while still keeping his characterization as someone dealing with mental illness.

[8.3] Despite stigmas around mental illness in real life, online affinity spaces can support connections among people who want to talk about their mental illnesses anonymously (Parrott 2023). Such issues can also be explored through stories and fan fiction, using personal experiences to inform interpretations of characters and rewrite them in more socially transformative ways. In this case, we saw both focal group and fandom concerns around rehumanizing Josh's character and storyline.

9. Engaging issues of race and culture

[9.1] Lauren, who identifies as Asian American, chose to cosplay the character Hannah. This character is less popular across fandom spaces, most likely because this character is a wendigo monster for the majority of the game. Lauren chose to design her cosplay based on the character's appearance in the prologue where she and the character looked the most similar. Though the character's race was not specified in the game, the character's model identifies as Peruvian-Italian, and Hannah's family is sometimes interpreted by fans as racially mixed in fan fiction descriptions. In horror genres, such characters are often marginalized by being killed off or turned into monsters, as is the case with Hannah as a fixed event in the game.

[9.2] At the convention, the group decided to take a picture at a flowery Japan-themed Funimation photo booth. This prompted the cosplayers to consider why and when their characters might go to Japan together. As they were approaching the booth, Karis commented to Sahara: "This is the alternate universe if we [the characters] had decided to go to Japan instead of going to Josh's terrible party." During a photo, the group speculated about what it meant in terms of the video game for all their characters to be human and present together in Japan (excerpt 2).

[9.3] Karis [to Lauren]: This is also, what if you were still alive.

Lauren: Am I still alive?

Sahara: This is an alternate universe.

Karis: Yeah alternate universe.

Figure 6. Alternate universe photo shoot.

[9.4] Because Lauren as a cosplayer was an important part of the group and because this cosplayer chose the character's human form and not the monster form, the humanized character became more central to the group storytelling as well. Karis proposes that this picture could take place in a speculative space outside the game where Lauren's character could still present with the other teen characters as human. Together, the group imagines an alternative universe where Hannah will never need to transform into a monster. Notably, none of the top fan fictions reviewed in this study reimagined Hannah as central in this way, meaning that Lauren's choice of cosplay uniquely foregrounded the character in a way the game did not.

[9.5] Though critics raise Indigenous appropriation as a prominent issue with the game, we saw only a little engagement with such issues in either live streaming, cosplaying choices, or fan fiction. Though Lauren chose to cosplay Hannah, she intentionally chose her human form and not the wendigo transformation. Both in the live streaming and in fan fiction notes, fans sometimes acknowledged that the representation of Cree mythology and cultural artifacts in the game was inaccurate and appropriative. Other writers bracketed their lack of knowledge about Cree mythology and culture in their fan fiction introductions. Overall, we found that few of the top fan fictions took up elements of Indigenous culture at all, which could be seen as a critique of the game's use of such elements and refusal to engage in appropriative content.

[9.6] One example of uptake around the Indigenous elements of the game included a fan fiction creator sharing their interpretations of Indigenous material and imagery in the game. One popular alternate universe (AU) that Sahara knew, named ExorJosh, contains a storyline where Josh's parents try to remove the wendigo curse through an Indigenous ritual. The creator of the AU describes how having an Indigenous connection was important to them because of the Cree storylines in the video game, leading them to do some research about the plausibility of an Indigenous exorcism. When explaining how that might fit within the in-game universe, the creator speculated that references to communications with the local tribe and the presence of Aboriginal artworks within Josh's family's home could imply that Josh's family has some Native American ancestry. This interpretation deepens the connection between the main characters and the Cree story elements, attempting to make this representation more central. However, the creator acknowledged that their research resulted in limited evidence regarding the possibility of an Indigenous exorcism of a wendigo spirit. We note the complexity of this uptake, that this creator's discussion shows a critical recognition of the game's surface use of Indigenous cultural elements while continuing to inaccurately take up Indigenous culture in non-Native storytelling, an appropriative storytelling move often perpetuated in fantasy contexts (Eddy 2020).

10. Discussion

[10.1] Video games with multiple branching story paths can allow fans to make decisions to subvert genre tropes. Video games like Undertale (Toby Fox, 2015) embrace this mechanic explicitly, with its fan-named pacificist path that allows players to choose to subvert more violent video game tropes (McElroy 2015). Even when branching story pathways are not inherently critical, players can choose to creatively challenge the storyline through counterplaying (losing on purpose to protest mechanics) or performing oppositional readings of the game (Nguyen 2016). Players may also create metagames to subvert marginalizing storylines or mechanics, such as blind players using fandom paratexts to accomplish speedruns despite inaccessible designs (Boluk and LeMieux 2017).

[10.2] Because some story elements in Until Dawn are fixed while others allow for more choice, Until Dawn affords a complex context for examining actualized textualities (Jennings 2015), including a multitude of ways that fans could critically engage with interpretation or restorying (Thomas 2019). We saw players disrupting certain stereotypes like gender archetypes through their choice of pathway, while for issues like sexuality that were less present in the game, players had to depart to mediums like fan fiction for more substantial restorying. Though less often critically engaged, issues of Indigenous cultural appropriation were resisted by critiquing the game mechanics or through fan fiction metatexts bracketing the author's lack of knowledge about these cultures as well as describing intentional choices to leave these appropriative elements out.

[10.3] Fans were interested in recentering characters who were marginalized by the game, particularly female characters. Although the most popular relationship in AO3 tags was a male/male pairing, female characters appeared often in these popular works with central roles. In most of the Chris/Josh fan fictions reviewed by the authors, Ashley was present and addressed by the writers as a past romantic interest rather than being brushed aside, killed off, or disparaged. This cordial portrayal of the three characters' friendships allowed for both queer and female representation and did not put different marginalized representations in competition (e.g., Thomas 2019). Additionally, the cosplaying team chose to centralize certain female characters who were given relatively less focus within the game. Sahara chose to cosplay as Jess, who among playable characters has the second shortest playtime and the earliest potential death. Lauren chose to cosplay as Hannah, a character who only appears in human form in the prologue of the game and has no playtime whatsoever. By choosing characters on the outskirts of the storyline that resonated with them, we see the cosplayers bringing them more clearly into focus.

[10.4] We were also interested in how different textual mediums afforded different possibilities for critical interpretation and restorying. Sahara, who identifies as having a mental illness, made many in-game moves to humanize the character Josh and his mental illness. This disruption only emerged during in-game discourse, not while cosplaying. We theorize that fan-cosplayers at the convention could more easily disrupt horror tropes that aligned with their physically visible and socially recognizable identities, whereas fans online can more easily engage with more invisible identities like mental illness.

[10.5] Across fan fiction, live streaming, and cosplaying, we saw minimal critical uptake around issues of race and Indigenous appropriation. We note that in our data, white cosplayers in the focal group chose to cosplay white-coded characters, which avoided cross-racial cosplay erasure of characters of color (miller 2020) but did not allow us to examine ephemeral restorying interactions for several of the nonchosen characters whose storylines critics identify as problematic (such as Matt, the only Black male character, who has the least playable time in-game and far fewer fan fictions). We suggest further studies could examine how critical play by cosplayers of color could recenter marginalized characters. Though traditional texts have been examined for their potential to dehumanize or inspire empathy (Lindhé 2021), less has been done around how embodied textual practices like cosplaying characters can support critical empathy for media texts like video games. In the cosplaying data, we saw that Lauren's choice to cosplay Hannah humanized her and made her more central to reimagined storylines than popular fan fiction storylines did.

11. Conclusion

[11.1] This case furthers our understanding of how critical transliteracies practices are enacted by fans within fandom communities across different communities, contexts, and modalities. This matters as we seek to understand how to foster criticality in fandoms to resist problematic and neoliberal turns in media industries. Multisited analyses like these show how popular texts like video games can serve as engaging and productive contexts for critical engagement. When there are possibilities for different endings, players can and do leverage paratexts such as gaming guides or videos to help them navigate toward endings they want. Fans engage in complex literacy practices such as critical restorying through engagement with fan fiction and cosplay, diverging from canonical storylines to make happy endings the game never provided, or using affective cosplaying connections (Lamerichs 2018) to humanize and complicate characters that were flattened by the game or other fans. As we think about innovative classroom pedagogies that integrate video games as class texts (Nash and Brady 2022) as well as calls to disrupt ways that video gaming communities can perpetuate racism and sexism (Gray and Leonard 2018), we suggest that parents and educators can support youth in learning about applying critical perspectives for video game texts that are meaningful to them by jointly discussing how individual players and the surrounding fandoms engage (or hesitate to engage) in collective critical endeavors together.