1. Introduction

[1.1] Given his death over four hundred years ago, one might assume that we have reached a point of critical saturation with hand-wringing about Shakespeare and the state of education and culture. Alas, we have not. These days, we find amid disingenuous cries of cancel culture and wokeness the fear that Shakespeare is being replaced in school and university curricula. (Spoiler: He isn't.) But even supposing this rumor were true, if we suddenly stopped teaching Shakespeare, he would not vanish like Ariel's spirits at the end of The Tempest. Shakespeare is so inextricably woven into Anglo-American culture that it would take more than a few hypothetical English departments to nudge him off his pedestal, however one feels about his presence there. These discussions, however heated and mischaracterized, have at least given scholars room to address Shakespeare's hallowed place in the English canon.

[1.2] Because, in the end, William Shakespeare was just a man from Stratford-upon-Avon—educated within the standards of his time, not very well traveled, a boringly middle-class white man. As Paul Menzer recently observed, "the facts we know about Shakespeare's life would fit on the back of a postcard" (2023, xi). He was married with children but somehow ended up a considerable distance from them, in London, where he started an unexpected career as a playwright and poet. Thirty-seven(ish) plays, 154 sonnets, and several narrative poems later, he returned to Stratford, where he supposedly died on the same day that he was born, surrounded—for better or worse—by the remainder of his family. And even that seemingly straightforward tale is fraught with missing years, unexplained absences and presences, and paper trails that lead nowhere. So much of what we think we know, what we assume, about William Shakespeare is, at worst, flatly untrue and, at best, merely unprovable. How do we get from this long string of documentary lacunae to the central figure of the English literary canon, and what can that journey reveal about different modes of reading and engagement? The answer, I argue, lies in what Anna Wilson calls "fannish hermeneutics"—in essence, a mode of affective reading that emphasizes an emotional connection to the text, thus operating in contrast to the manner of reading favored by academic institutions, and which can tell us far more about the reader than about Shakespeare (2016, ¶ 1.1). While I certainly do not propose to elevate one reading mode over the other—after all, at their worst, one reeks of pedantry and the other gave us the anti-Stratfordians—I wish to explore in this article how readings of Shakespeare's sonnets reflect different forms of fannish engagement and hermeneutics.

[1.3] Shakespeare scholars are well aware of his collaborators, his sources, and the larger context of early modern literary and theatrical practice—where the lines on the page might have come not from a single playwright but from actors improvising, or quotations from a contemporary play or poem—but the centrality of Shakespeare to the white Anglophone canon is still predicated on an assumption of individual genius that developed in concert with copyright law as well as the nascent British Empire over the course of the eighteenth century (Woodmansee 1984). This manifested in the flurry of divergent responses—appearing in the New Yorker, the Guardian, and on NPR's All Things Considered, among others—to the 2016 New Oxford Shakespeare, which designated Shakespeare as second or third author on a number of plays across his career (note 1). Emma Smith has astutely remarked that the reluctance to accept Shakespeare's plays as potentially collaborative works "reveals just how much the question of authorship is intercalated with that of literary value, in an economy in which Shakespeare = gold and other writer = dross" (2008, 629). Menzer similarly characterizes the seemingly never-ending dispute over Shakespeare's authorship, partial or otherwise, as "a contest between those who would put Shakespeare on a pedestal and those who would knock him off" (2023, xii). Nor do these arguments restrict themselves to the plays attributed partly or fully to Shakespeare; they also appear in discussions of his poetry which, while not likely to have been collaborative works, were nonetheless part of a larger literary conversation happening in the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods.

[1.4] Nearly every popular depiction of Shakespeare's life—from John Madden and Tom Stoppard's Oscar-winning Shakespeare in Love (1998) to Roland Emmerich's much-derided Anonymous (2011) and writer Ben Elton's All Is True (2018), from innumerable novels to TV series Will (2017) and Upstart Crow (2016–20)—makes some attempt, seriously or otherwise, to identify the addressees of his famous sonnet collection, the so-called Dark Lady and Fair Youth. As Douglas Lanier has observed, "no matter how historically faithful they choose to be, popular portrayals of Shakespeare (and scholarly ones as well) inevitably serve ideological ends" (2002, 113). The temptation to conflate the "I" of these verses with Shakespeare himself took hold in the eighteenth century and has persisted despite an abundance of proof and context that argues the contrary, thus suggesting an affective resonance to that conflation and the potentially useful approach of delineating what fans and fan studies scholars term fanon Shakespeare from canon Shakespeare—concepts that the next section will unpack in greater detail. We know notoriously little about the latter, and while the desire to speculate on the former makes perfect sense, it is a path fraught with misogynist, classist, and racist—in the case of the Dark Lady—assumptions that Shakespeare studies is still untangling today.

2. Fannish reading

[2.1] Abigail Derecho's characterization of fan community storytelling as archontic, drawing upon Derrida's framework of the endless archive, pushed back against the assumption in the first generation of fan studies scholarship that automatically subordinated fan works to original works, arguing that "when we conceive of the 'smallest' work as a repetition, with a difference, of an earlier work, we understand that the smaller work can have a great deal of resonance with the previously existing one" (2006, 74). In response, Catherine Tosenberger proposed a "recursive" model of storytelling, which she argues "contains the greater assumption of agency, of action, for the activities of fans" (2014, 15; 2007, 14–26). Abigail de Kosnik has since combined these two threads into the concept of archontic production, or "the process by which audiences/receivers of mass-produced and mass-distributed cultural texts [...] seize hold of these commodities as a vast archive of usable resources, from which they select desirable parts as the raw material for their own revisions and variations" (2016, 277).

[2.2] De Kosnik, Cait Coker, Anna Wilson, and I have also discussed parallels, connections, and avenues of inquiry between premodern literary culture (primarily in Europe) and contemporary fan communities, addressing the potentialities and limitations of these comparisons. As Coker recently argued, "a judicious revision of the term [fan fiction] has the potential to unlock how we read fan works across a spectrum of published and 'unpublished' material and gain a more nuanced picture of the history of fandom specifically and women's writing generally" (2021, 189). Wilson similarly observes that "fan fiction troubles the reader/writer binary, drawing attention to the ways in which readers collectively reauthor texts through marginal annotation and commentary, textual editing, translation, and other interpretive acts" and that its "authorial indeterminacy—which is actually a failure to fit into categories of authorship shaped by the marketplace—demands reexamination of what we mean by authorship" (2021, ¶ 3.6). To this heady cocktail, I also wish to add a last thought from Anne Jamison, who specifies that "no fic pretends to be an autonomous work of art," that fan fiction is constantly revealing its "props and sources" not for lack of skill, but as a deliberate choice: "A work of fic might stand on its own as a story—it might be intelligible to readers unfamiliar with its source—but that's not its point" (2013, 14).

[2.3] In the case of Shakespeare, this can entail regarding Holinshed's Chronicles or Plutarch's Lives not simply as sources for the plotlines and characters in, respectively, the English history plays and the Roman plays, but as preexisting texts that Shakespeare and his collaborators transformed into the plays we know today. After all, what is The Tragedy of King Lear if not a canon divergence AU of the anonymous mid-1590s play The History of King Leir where instead of an eleventh-hour victory, everyone dies horribly? Shakespeare and his fellow playwrights were also able to assume a certain level of awareness on the part of their initial audiences—a passing reference to, for instance, "Mistress Shore" in Shakespeare's Richard III, a character who does not even appear onstage, would have drawn laughs because, as I used to tell my students, Shore was the Marilyn Monroe of her day, a woman whose history inspired the public to turn her into a sex object (Finn 2015). This falls within Jamison's description of fan fiction as fiction that calls deliberate attention to its source material—to the gaps in that material, as well as the scaffolding that material provides.

[2.4] We can see in this kind of recharacterization a push against the postromantic idea of originality and, by extension, the idea of Shakespeare as solitary genius. Indeed, I would argue that the very trope of Shakespeare-as-genius is, in its purest sense, fanon or, per Karen Hellekson and Kristina Busse's definition, "the events created by the fan community in a particular fandom and repeated pervasively throughout the fantext. Fanon often creates particular details of character readings even though canon does not fully support it—or, at times, outright contradicts it" (2006, 9). The word "canon" is, especially now, fraught with implications ranging from Eurocentrism to white supremacy, from classism to colonialism, but in the fannish sense of the word, canon is merely the content of the source text, whatever that text may be. Fanon, conversely, derives from the fandom itself—elements that are being read into the text by the larger fan community, an extension of the more individualized concept of the head canon (note 2). To borrow Anna Wilson's formulation, these readings represent "a mental technology that facilitates understanding of a text by means of an affective hermeneutics—a set of ways of gaining knowledge through feeling" (2016, ¶ 1.4). However, the fanon of Shakespeare as individual, self-contained genius has become an intrinsic part of Shakespeare studies whether or not one subscribes to it.

[2.5] Fanon operates as a two-way street, being read into the fandom by the fans, and then shifting outward from the fandom to the object itself as creators begin to embrace it. Indeed, E. J. Nielsen has called attention to the relative paucity of scholarship on fan art and reads fan art as iconography "created communally by fan artists" that "allow[s] images to be successfully read by fans independent of the style, medium, or degree of realism present in the artwork" (2022, 208). While fan art is outside the scope of this article, there is great potential for using Nielsen's framework to analyze visual representations of Shakespeare and his works. With that in mind, however, what I want to focus on here is fanon about Shakespeare the individual and how that manifests particularly in readings of the sonnets.

3. Shakespeare's sonnets: Canon, fanon, or a strange third thing?

[3.1] The earliest reference to Shakespeare writing sonnets appears in Francis Meres's Palladis Tamia (1598), where he mentions Shakespeare's "sugred [sic] Sonnets among his private friends" (281v–282r). Early versions of Sonnets 138 and 144 appeared the following year, alongside verse fragments from Love's Labor's Lost and a variety of unattributed and/or misattributed poems by other London-based writers, in an octavo volume titled The Passionate Pilgrime. By W. Shakespeare (1599) and printed by William Jaggard (note 3). Between 1599 and 1609, no poems by Shakespeare appeared in print; his narrative poems The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis both date from the early 1590s, and his literary output during that decade seems to have been restricted to plays. In 1609, however, a quarto volume was published by Thomas Thorpe, titled simply Shake-speares Sonnets. Neuer Before Imprinted. (Which, perhaps, answers the question of whether Shakespeare authorized Jaggard's printing of his poems ten years earlier.) This edition comprises 154 sonnets and a longer narrative poem titled "A Lover's Complaint." The first 126 sonnets are addressed to a Fair Youth, and the remaining 28 are addressed to a Dark Lady, neither of whom is given a name or any other identifying marker.

[3.2] The most popular sonnet sequences produced in the 1590s follow a similar structure: a selection of sonnets, usually addressed to one person, followed by one or two longer narrative poems. They also tend to follow similar typographical and stylistic conventions—for example, roman or italic, rather than black letter–typeface, the careful use of blank space and arabesques—suggesting that they were being produced with particular audience expectations in mind (Bland 1998, 114–19; Finn 2015, 83–86). The earliest known examples of the sonnet in English are those of Thomas Wyatt, who translated several of Petrarch's fourteenth-century Canzoniere during the reign of Henry VIII. The late Elizabethan craze for sonnet sequences, however, can potentially be traced to a pirated edition of Sir Philip Sidney's Astrophel and Stella printed in 1591 (note 4). This edition contained not only an unauthorized version of Sidney's sonnets but also several of Samuel Daniel's composition that were misattributed to Sidney. To set the record straight, Daniel had his own authoritative edition of fifty sonnets and several longer poems printed in 1592 under the title Delia. Contayning certayne Sonnets: vvith the complaint of Rosamond. This trend quickly took hold, with poets such as Michael Drayton, Thomas Lodge, and Edmund Spenser producing sonnet collections within the next five years. Sidney's own collection was reprinted under the careful eye of his sister, the Countess of Pembroke, and it would not be unreasonable to say that sonnet sequences were the height of fashion during the last decade of Elizabeth I's reign. Many of these sequences, particularly Daniel's and Drayton's, were revised and reprinted over the next ten to fifteen years; as the late Katherine Duncan-Jones observed, "a sonnet sequence [...] is almost bound to be the product of several second thoughts and rearrangements" (2010, 13).

[3.3] Shakespeare's 1609 text, therefore, likely represents one version of a series of poems that he had been tinkering with for more than a decade. The inclusion of "The Lover's Complaint," furthermore, suggests that Daniel's Delia was his primary model, an observation first made by literary critic Edmond Malone in his supplement to a 1778 edition of Shakespeare's plays edited by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens (1780, 581n3). Duncan-Jones linked the 1609 publication date to an outbreak of plague that closed the London theaters, thus leaving the playwright in search of alternate sources of income and patronage—a relatable problem in our age of gig economies, freelancing, and a global pandemic. While not a particularly romantic interpretation, given what we know about Shakespeare's business ventures in the Globe Theatre, it is certainly plausible. Printer Thomas Thorpe's dedication to "Mr. W.H." may refer to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke and nephew of Sir Philip Sidney, a well-known patron of literature and a sometime poet himself, and given that the First Folio of 1623 is dedicated to Herbert, it is not unreasonable to suppose that the 1609 sonnet volume might be as well. Since the dedication is signed "T.T." rather than "W.S.," however, it isn't even clear that Shakespeare was directly involved: yet another mystery to add to the long list of Shakespearean enigmas. In all, if viewed contextually, Shakespeare's sonnets are operating within the specific conventions of a popular poetic genre rather than expressing deep personal feelings, as the fanon would suggest.

4. Shakespeare and the myth of authorship

[4.1] As Emma Smith observes, "the question of who wrote Shakespeare scarcely existed in print before the nineteenth century, and can thus usefully be seen as a product of that period," when "the dominant mode of Shakespeare scholarship was [...] broadly biographical in tenor" (2008, 619–20). In contrast to what Louise Geddes and Valerie Fazel have described as "the Shakespeare multiverse" consisting of "everything Shakespeare from the early modern quartos and the 1623 Folio to 21st century fanfics," prior to the late 1780s, the sonnets had not been considered part of Shakespeare's canonical works (2021, 4). They are not included, for instance, in what is considered the first modern edition, Nicholas Rowe's six-volume Works of Mr. William Shakespeare (1709). Rowe was also the first to attempt a biography of Shakespeare, appended to his edition; as Paul Menzer remarks, of "Rowe's many editorial innovations, the most enduring is the idea that Shakespeare's life might matter to his art, and to us" (2023, 13). Multiple anecdotes about Shakespeare's life that the tourist industry and even some scholars have taken for granted—like Queen Elizabeth I requesting a comedy starring Sir John Falstaff that became The Merry Wives of Windsor—are, in fact, Nicholas Rowe's head canons. It is perhaps less surprising then that when the sonnets do appear in Rowe's nine-volume edition published five years later in 1714, it is as "Poems on Several Occasions," arranged in a different order from the 1609 quarto, with some combined into longer poems, interspersed with snippets from plays and poems not by Shakespeare, and all given titles such as "A Disconsolation" (Sonnets 27–29) or "The Picture of True Love" (Sonnet 116) (1714, 119–20, 146). It was Edmond Malone who set the record more or less straight in his Supplement to the Edition of Shakespeare's Plays Published in 1778 by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens [...] to which are subjoined the Genuine Poems of the Same Author (1780). However, in his quest to claim the sonnets as "The Genuine Poems" written by Shakespeare, Malone followed Rowe down the biographical rabbit hole and read the "I" as a representation of Shakespeare's own perspective. While this has been known to happen with other sonnets, either as individual poems or in sequence—for example, using Thomas Wyatt's "Whoso list to hunt" (1520s) to speculate on his relationship with Anne Boleyn, or attempting to identify Dante's Beatrice or Petrarch's Laura—the fanon surrounding Shakespeare has made his sonnet sequence a fertile breeding ground for biographical speculation.

[4.2] It is also not a coincidence that biographical readings of the sonnets—and, indeed, of the plays—began around the same time that Shakespeare was making his way toward the center of the burgeoning English literary canon. The eighteenth and particularly the nineteenth centuries saw the growth of a Shakespeare industry predicated on his quintessential Englishness, and his works became an integral part of the colonial project, particularly in India. Closer to home, the efforts of Rowe, Malone, Samuel Johnson, David Garrick, and others transformed the Shakespeare of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—the glovemaker's son from Stratford-upon-Avon who made it as a playwright in the big city—into what Martha Woodmansee calls an "original genius," whose "inspiration came to be regarded as emanating not from outside or above, but from within the writer himself" (1984, 427). Gone were his collaborators, the improvising actors, the other playwrights whose work he built on and worked with. Even the sources for his plays and the larger cultural contexts of Elizabethan and Jacobean England were overshadowed by the fanon of individual brilliance, God—or some other divine force—reaching down into the man Shakespeare's head and filling it with already-formed masterpieces. But the genius was missing a muse, an emotional anchor, and they found her in the Dark Lady of the sonnets—ignoring, or uncomfortably dismissing, the possibility of same-sex affection for the Fair Youth. This reading also rejects the disingenuous misogyny of the last twenty-six sonnets, which are hardly flattering to the Dark Lady. According to Kim F. Hall's foundational study, "Positing a mistress as dark allows the poet to turn her white, to refashion her into an acceptable object of Platonic love and admiration. The loveliness of these Petrarchan beauties, despite their color, represents not their seductive power but the poet's power in bringing them to light" (1995, 67).

[4.3] In short, whoever the Dark Lady was, if she even existed, is largely irrelevant to readings of the sonnets, given the literary conventions that prized the poet's skill over the object of his literary affections. Hall has also convincingly argued that the "whitening of dark ladies reveals the contradictory impulses of a poetic that simultaneously wishes to 'enrich' the language with new world matter and to deny excessive involvement in foreign difference" (71). Thus, Shakespeare's sonnets—and those to which they are responding—are operating within the specific context of the English colonial project, which was beginning to gain traction during Shakespeare's lifetime, though biographical readings usually avoid that context to focus on a string of real-world candidates. As Ambereen Dadabhoy and Nedda Mehdizadeh observe, these kinds of studies imply "a race-neutral or racially innocent Shakespeare and early modern period, absolving the era and its writers from complicity in its emerging racialized ideologies within an array of literary and cultural productions" (2023, 11). Similar allusions to colonization appear in sonnets by John Donne and Edmund Spenser, among others, indicating that it was a relatively common trope within the genre (Adams 2021).

[4.4] The pervasiveness of biographical readings has also impacted the various women proposed for the Dark Lady. In the case of Aemilia Bassano Lanyer, for instance, who A. L. Rowse identified in 1973 as the Dark Lady, speculation on her relationship with Shakespeare has threatened to overshadow her own literary output. In 2018, The Atlantic ran a series of essays claiming that Shakespeare's plays and poetry were in fact written by Lanyer, while largely ignoring Lanyer's known body of work. While I understand why people might want to imagine that works so central to the English canon were written by a woman, we already know what Aemilia Lanyer wrote—the excellent Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611)—because she published it under her own name. This kind of disingenuous misreading, rooted in the fanon that Shakespeare's sonnets are autobiographical, places speculation on the Dark Lady's identity firmly within the other major trend in sonnet reading that developed from the late eighteenth century into the nineteenth, and that still trails behind Shakespeare studies like toilet paper on a shoe.

[4.5] Anti-Stratfordians—those who believe in a far-reaching conspiracy to cover up the true author of the works of Shakespeare, whether that be Christopher Marlowe, Francis Bacon, Edward de Vere, or Aemilia Lanyer, among others—frequently use the sonnets as proof for their conjectures. Since we know so little about them and about the intended recipient(s), if there were any, the sonnets, even more than the plays, are a blank slate onto which conspiracy theorists of all stripes can project whatever they want. Anti-Stratfordians therefore represent the downside of fannish reading—the ability to use fanon to read into the source text certain interpretations that have no actual basis in that text, and then to create a recursive loop where everything points to that interpretation. Shakespeare's works, to the anti-Stratfordian reader, are filled with "coded messages, cryptographical challenges to social and political orthodoxies, which their author wanted to promulgate but could not own" (Smith 2023, 621) (note 5). Moreover, the interpretative gymnastics required to "crack the hermeneutic code does not undermine it or make it less plausible; rather, the investigator into the question of authorship must enter into the encoded, anagrammatical consciousness of Renaissance intellectual cabbalism to retrieve the meanings so carefully hidden within plays which seem to (almost) all the world innocent of their secret symbolism" (621–22). This kind of willful misreading is well known among both fans and those who study them, from Supernatural (2005–20) to Sherlock (2010–17) to the many iterations of the Marvelverse, and can unfortunately also be seen across mainstream media and political culture in the Anglo-American sphere to defend racist, sexist, classist, ableist, and other reactionary viewpoints.

[4.6] While I originally invoked the idea of a recursive loop as a positive framework to discuss the creation, enjoyment, and sharing of fan works, it also manifests in more negative ways in fan spaces, sometimes, though not always, falling into the nebulous category of antifandom. One useful formulation comes from E. J. Nielsen, who writes the following about toxic fan responses to queer baiting: "It is neither transformative, since it claims to be reading the text in accordance with (presumed) authorial intent, nor is it affirmational, since the show's creators themselves reject it. Instead [...] a group made up primarily of young female fans [...] use traditionally transformative fan tools (social media, fanworks, meta) to instead reify their affirmational reading as the only correct way of reading the text. They then use these same tools to 'police' other fans" (2019, 84).

[4.7] Writing for Teen Vogue in 2022, journalist and essayist Stitch has observed a similar pattern in fans' engagement with villainous characters, where "people internalize their right to do whatever they want at other people's expense, if only backed by the right sob story and buzzwords" (2022). That this approach to fanon is almost exclusively confined to white villains has not escaped notice either; Stitch, Rukmini Pande, and other fan journalists and scholars have called out these behaviors in fan spaces, and the recent campaign #EndOTWRacism has coalesced around these criticisms, among others. As Pande points out, "white crime and white evil are considered almost inherently worthy of exploration and nuance in a way that is simply not available for nonwhite characters in similar molds" (2018, 7). Shakespeare studies also faces similar criticism, especially in discussions of the so-called race plays, like Othello and Merchant of Venice (Dadabhoy and Mehdizadeh 2022; Brown 2023). However, the recursive loop that fans create to justify these flawed readings is what I wish to focus on here: no matter what evidence is presented, all of it can be contorted to point to the interpretation the fan desires.

[4.8] The Twitter exchange excerpted in figures 1 and 2 offers an illustrative example. One participant provides factual evidence that Shakespeare and his contemporary Ben Jonson both attended English grammar schools and had similar educational backgrounds. The other insists that because "no Latin Grammar School taught French or Italian or about falconry or the law or any of the other dozens of areas of knowledge with which the Bard is confident and conversant," Shakespeare couldn't possibly have gone from "being burdened by 3 children at 21 to writing the Henry VI trilogy at 28." Never mind that, as the first participant correctly observes, "you don't have to be an expert on things to write about them convincingly enough for dialogue in a play," the second participant's view is that Shakespeare not being an expert on every aspect of his plays means he did not write them. In short, any element within Shakespeare's oeuvre, however small or seemingly insignificant, that might indicate a connection to, for instance, the Earl of Oxford confirms that Oxford wrote them; anything to the contrary, including the fact that Oxford died in 1604 and new texts by Shakespeare, including the sonnets, continued to appear onstage and in print, is merely part of the cover-up. I wish I could say this kind of fannish reading restricts itself to literature and/or popular media, but these willful misreadings pop up everywhere, including, perhaps most egregiously, in mainstream news and political discussion.

Figure 1. Screenshot from a Twitter exchange on June 21, 2023, regarding the putative authorship of Shakespeare's plays. Names redacted.

Figure 2. Screenshot from the same Twitter exchange, providing a response to the first discussion. Names redacted.

5. The sonnets as fannish shorthand

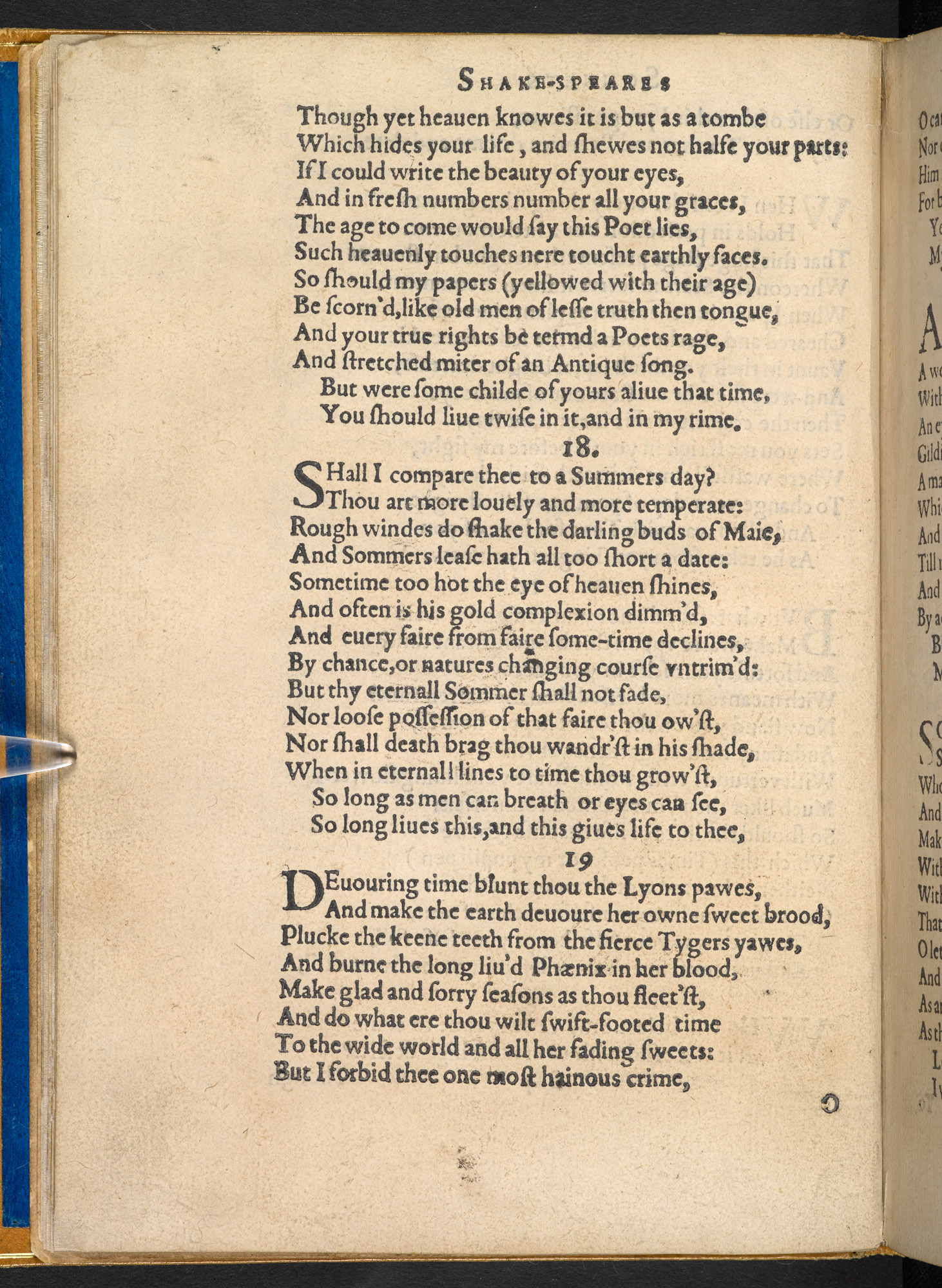

[5.1] I wish to conclude with some fannish close reading of specific sonnets. While Sonnet 116 is probably quoted equally often—especially at weddings—Sonnet 18 has become an Anglo-American shorthand for Shakespeare. Within the sequence itself, Sonnet 18 follows a series of exhortations to the Fair Youth to have children in order to increase his glory (figure 3). It is the first to emphasize the power of the poet—and poetry in general—to immortalize the Fair Youth: "So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life to thee." The quotations of this sonnet discussed below reinscribe it into a framework that sidesteps the original context altogether to fall into the fanon interpretation of Shakespeare expressing his true feelings to a specific woman in his life. They all involve creators who would call themselves fans of Shakespeare, much as some would resist the classification of their work as fan fiction.

Figure 3. Sonnet 18, from the 1609 edition of Shake-speare's Sonnets. Image appears with kind permission of the British Library.

[5.2] The first example appears in the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love, which itself operates as an elaborate—albeit well-funded, publicized, and much-lauded—fan text. Screenwriter Tom Stoppard was a veteran of Shakespearean adaptations, having transformed Hamlet into the existentialist dreamscape of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), and the film features a Shakespeare suffering from writer's block, discovering his new muse, and writing Romeo and Juliet. Wholly ignoring the play's documented source, Arthur Brooke's 1562 poem The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet, the Shakespeare of the film draws on his class-crossed love affair with the invented Lady Viola de Lesseps, the violent murder of Christopher Marlowe as an inspiration for Mercutio's death, and his own guilt and heartbreak for the play's tragic ending. It also allows for a brief collaboration between Shakespeare and Marlowe, who suggests the overall plot and characters of Romeo and Juliet early in the film. As Lanier remarks, however, Shakespeare in Love also uses this framing of art imitating life to undercut any homoerotic possibilities within Shakespeare's texts, including Sonnet 18. Lady Viola reads the first four lines while dressed as a young man, but "our knowledge of [her] true identity and the passionate affair between Will and Viola that underlies Romeo and Juliet tends to reduce these queer moments to fleeting counterpoint for a very straight love story" (2002, 126). In short, despite the fannish trappings of Shakespeare in Love—its snappy dialogue, the hundreds of Easter eggs tucked throughout the film for those familiar with early modern drama—it ultimately follows a more conservative reading of the sonnets rooted in Victorian, rather than Elizabethan, mores. A search of fan fiction based on the film on Archive of Our Own, however, yields as many relationship tags featuring Shakespeare and Marlowe as Shakespeare and Lady Viola, and several with the three of them as a romantic triad.

[5.3] The 2007 Doctor Who episode 3.2 "The Shakespeare Code" persists in addressing Sonnet 18 to a woman, but does so within its own subversive context as the woman in question is played by Black actress Freema Agyeman, and her racial status in Elizabethan London is frequently addressed. Moreover, while the sonnet itself is not addressed to a fair youth, the fact that Shakespeare flirts with both the Doctor and his companion Martha allows greater room for interpretation. The Doctor's gleeful aside that "fifty-seven academics just punched the air" is both a metacommentary on the successful scholarly interpretation of homoerotic subtext in Shakespeare's works and an expression of joy that William Shakespeare, the object of his fandom, is flirting with him. This cheeky, sideways glance at homoeroticism also hews far closer to the interpretations of Shakespeare found on Tumblr and Archive of Our Own than the straightforward heterosexual love story of Shakespeare in Love; even a quick glance at the character tag "William Shakespeare" on both sites unearths a range of slashy fan fiction, head canons, and fanon, including the perennially popular ship that pairs Shakespeare with his collaborator and rival Christopher Marlowe.

[5.4] In the 2018 film All Is True, an aged William Shakespeare (Kenneth Branagh) receives an unexpected visitor in Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton (Ian McKellen), and in a poignant and charged scene, they exchange recitations of Sonnet 29. Given the film's portrayal of Shakespeare returning home to Stratford at the end of his career and having to grapple with, among other things, the death of his son, Hamnet, seventeen years earlier, it is an appropriate choice, with its barely contained frustration and despair. But, as is so often the case with sonnets, the story hangs upon the turn. Branagh's Shakespeare speaks the final couplet—"For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings / That then I scorn to change my state with kings"—as a declaration of love that frames Southampton as the Fair Youth of the sonnets. Southampton's response is to recite the line in a completely different tone, one that, without contradicting Shakespeare, gently refutes this as the sole reading. A review on Slate by Isaac Butler refers to the film as "part fact, part fanfiction," and, given Branagh's affective engagement with Shakespeare as a writer and an institution over the entirety of his theatrical and film career, it's not surprising that it feels as personal as it does (2018). As Anna Blackwell observed in 2013 on the media reactions to the announcement that Branagh was directing the Marvel film Thor, "it is not merely that [...] critics view Branagh's career as being shaped by a singular theatrical tendency, but that this tendency must remain explicitly Shakespearean" (33). In this way, he is not dissimilar from the "fanboy auteurs" discussed by Suzanne Scott in that his Shakespearean origins serve as "fan credentials, which are narrativized and (self) promoted as an integral part of [his] appeal as a transmedia interpreter for audiences" (2013, 44). Branagh has made no secret of the fact that he is a Shakespeare fan as well as a theater maker, and if, as Anna Wilson observes, "fan fiction...provides an opportunity for readers and writers to mutually affirm their intimacy with a text and with its characters," the conversation between Shakespeare and Southampton in All Is True is a prime example of that kind of affective hermeneutics (2016, ¶ 2.4).

[5.5] Two more recent TV series feature Aemilia Lanyer as a character and, explicitly or implicitly, link her to the sonnets. The BBC comedy series Upstart Crow, discussed in Edel Semple's contribution to this issue, addressed the sonnets in the episode "Love Is Not Love" (1.4) and included both Lanyer (as the Dark Lady) and Wriothesley (as the Fair Youth) as comic relief. Will, a self-described "punk-rock Shakespeare" series that ran for a single season on the US network TNT, cast mixed-race actress and musician Jasmin Savoy Brown as Emilia Bassano and hinted at a possible romance, but the series' AO3 tags suggest that at least some viewers preferred to pair Shakespeare with bad boy Christopher Marlowe. More recently, references to Shakespeare's sonnets have proliferated in fan fiction for the Netflix adaptation of Sandman (2022–), the Amazon adapation of Good Omens (2019–), and Our Flag Means Death (OFMD) (2022–23), usually in a homoerotic context. Sonnet 18, for instance, is parodied in the first story in the OFMD fan fiction series Sonnets by Stede, concluding with "So long as I have eyes to worship thee, / So you remain the Lord of Fuckery" (Christine_Seaforth_Finch 2023). Given Shakespeare's own use of lines from other people's verses in his work, I like to think he would appreciate the humor.

[5.6] What then is the place of fannish reading in Shakespeare studies? Scholars focused on adaptation have historically focused their attention on professionally produced media, but the field has opened up significantly over the past decade, incorporating approaches and angles from fan studies to decenter the traditional canon and call greater attention to what amateur writers are doing with Shakespeare and why. Similarly, scholars in fan studies such as Anna Wilson, E. J. Nielsen, Evan Gledhill, Natasha Simonova, and Cait Coker and myself, among others, are turning to premodern writers as models of certain types of literary communities and engagements that foreshadow modern fan engagement and the production of transformative works. However, what may also prove useful is the emotional heft of fannish engagement; one of the problems we run into when dealing with anti-Stratfordians, for instance, is their profound distrust and dislike for academic institutions and their pride in being outside that hierarchy—what Lanier calls "a resistance focused on Shakespeare because there remains the residual sense that of all writers Shakespeare ought to be common cultural property rather than the domain of specialists" (2002, 140). Similar views have been known to come up in Shakespeare fandom, usually referring to school instructors who insisted upon too-rigid interpretations of the plays or poems (i.e., not gay enough). The turn to affect, as it's called, as well as calls to decolonize the canon have prompted many within both medieval and early modern studies to look more closely at their own positionality in relation to their objects of study, and fan studies offers a useful framework for these kinds of discussions. It won't bring us any closer to canon Shakespeare, but it might help us to better understand the fanon surrounding him and how best to approach it as teachers, as scholars, and as fans.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] This article began as a paper for the 2019 Fan Studies Network North America conference and was expanded into the 2021 Shakespeare at Kalamazoo lecture. I wish to thank Johnathan Pope for convening the 2019 session and Christina Gutierrez-Dennehy for inviting me to give the 2021 lecture. I also wish to thank E. J. Nielsen for their feedback on multiple versions and the two anonymous peer reviewers for identifying areas that needed additional scaffolding.