[0.3] Language is the threshold of all possible meaning and value. [It is] a condition for the production of subjects.

—Elizabeth Grosz, Sexual Subversions (1989)

1. Introduction

[1.1] Boys' love emerged in the late 1960s as women in Japan began creating commercial manga about young males in homoerotic relationships and self-publishing similarly themed fan comics called dōjinshi that featured young male characters taken from popular shōnen (boys) manga. The genre has gained popularity worldwide. Today it comprises not only manga and dōjinshi but also anime, fan fiction, artwork, fan and commercial videos, cosplay, video games, audio CDs, posters, movies, and other forms.

[1.2] There are clearly marked boys' love sections in major bookstores, popular manga such as Be-Boy Gold are sold in convenience stores in small towns, and visual kei bands, dressed in androgynous style, perform live and on television. "Otome Road," a nickname for the Higashi Ikebukuro district in Tokyo, has billboards and signboards of bishōnen (note 1) to entice passersby into stores selling boys' love products (figures 1, 2, and 3).

Figure 1. K Books billboards with boys' love advertising on a building in the Higashi Ikebukuro neighborhood, Tokyo, June 2009. (Photograph by the author.) [View larger image.]

Figure 2. Close-up of K Books outdoor display case, June 2009. (Photograph by the author.) [View larger image.]

Figure 3. Entrance to one of the boys' love stores in the Ikebukuro neighborhood, January 2011. (Mandarake, 3-15-2 Higashi Ikebukuro, Tokyo; photograph by the author.) [View larger image.]

[1.3] Boys' love is a creation of its fans. One of the most popular expressions of fan activity is Comic Market, a fan-organized event in Tokyo that in recent years has attracted more than 550,000 people over three days twice a year to buy or sell dōjinshi, which are created by circles—that is, small groups of friends or individual artists. Almost since Comic Market's inception in 1975, female fans of boys' love have outnumbered by large margins male fans of manga and anime featuring shōjo (adolescent girls), though recent preliminary research shows a shift to greater attendance by male fans (note 2).

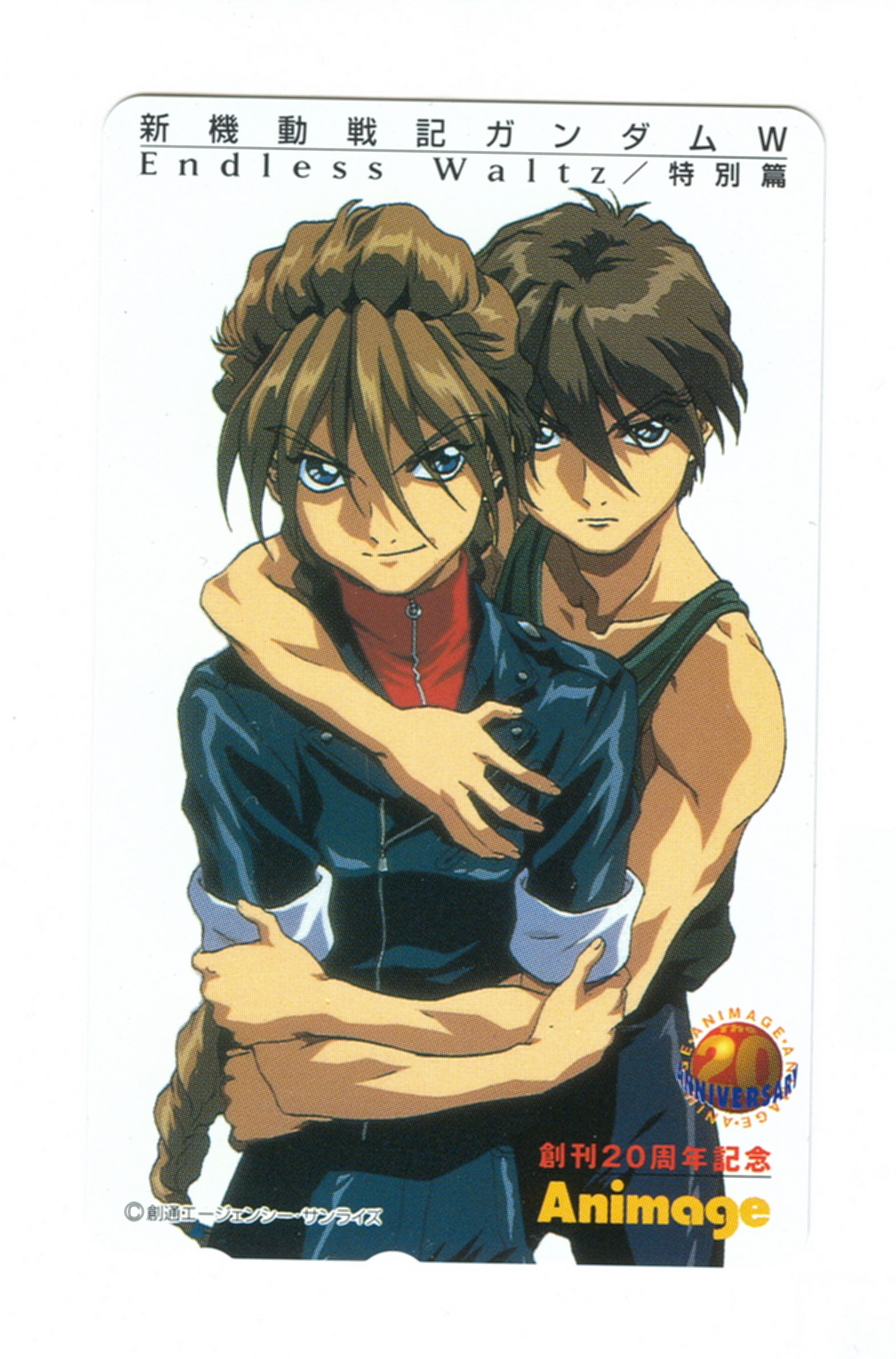

[1.4] Commercial publishers attend Comic Market to see how their characters are used in dōjinshi so that they may adapt their works to better satisfy fans. The canonical shōnen manga and anime used by many boys' love fans as the basis for their characters and settings rarely provide signs signifying overt erotic desire. Yet commercial publishers produce homoerotic-themed works using characters in best-selling children's manga, as homage to their boys' love readers, as in a Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation phone card featuring Gundam characters from the anime Endless Waltz (figure 4).

Figure 4. Endless Waltz. Duo Maxwell (left) and Heero Yuy. A Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation telephone card offered to readers by the magazine Animage (Tokyo) in 1998 to mark its 20th anniversary. That year, the anime Endless Waltz, featuring Duo, Heero, and other characters from the 1995–96 TV series Gundam Wing was released in Japan. [View larger image.]

[1.5] Boys' love's Western expression is most often called yaoi, which is an acronym of yamanashi, ochinashi, iminashi, meaning "no point, no climax, no meaning." The term was coined by a group of Japanese fans who titled a 1979 dōjinshi Rappori yaoi tokushu gou (Rappori: Special Yaoi Issue) (McHarry 2003). A Google search on June 26, 2011, returned about 37,000,000 Web pages with the word yaoi, a number that has grown steadily from approximately 135,000 pages on May 4, 2003 (note 3). Yaoi is seen on the Internet, in bookstores, and at anime/manga conventions, most notably Yaoi-Con, which has been held annually in or near San Francisco since 2001. Yaoi authors, artists, and consumers post comments, stories, and artwork to Web sites, social media sites such as Twitter, YouTube, LiveJournal, Facebook, and deviantART, to fan fiction archives such as FanFiction.net, and to discussion groups such as the Yaoi-Con Forums. One post may stimulate multiple comments. A work in one form, such as a story, may inspire works in another, such as illustration (figures 5 and 6). Although there are significant differences in content, form, and fan practices inside and outside Japan, I use the term "boys' love" to include both regions (note 4).

Figure 5. Lorialet, Freeport fan art, August 26, 2005. [View larger image.]

Figure 6. Randi Smith, "The Call" undated Freeport fan art. [View larger image.]

2. Identity

[2.1] Boys' love is strongly anti-identitarian around gender identity. In earlier work about boys' love, I argued that

[2.2] It portrays free-floating conceptions of self, one that refuses identity (including as hetero, homo, or bi), even as this self grounds itself in a male body and affirms the desirability of male-male eroticism. (McHarry 2007, 184)

[2.3] Both (or more) of the partners in a relationship lack the cultural accretions of masculinity normative in the West and in Japan. By removing these notions of masculinity—by "ungendering" masculinity—yaoi and boys' love fans eliminate barriers that impede their characters from bonding. (McHarry 2011, 126–28)

[2.4] The partners act on space and time. They may do so to acquire subjectivity. (McHarry 2010, 182–83)

[2.5] Identity formation is central to subject formation. It comprises actions taken by the self as well as by others on its behalf (Butler 2004, 128). Identity creates a space and a state for oneself to cohere around ideas. This coherence may be fictive, as in Lee Edelman's characterization of a gender identity of "homo" (1994, xix), but the barriers erected around it are real. As it includes, identity excludes.

[2.6] Language is also a condition for a subject's formation. In Elizabeth Grosz's characterization, it is "the threshold of all possible meaning and value" (1989, 39). But identity, in an attempt to maintain its coherence, defends itself against language. As Edelman described it, "To enter into language is always to be sundered into identity and to be imbued with a need to defend that identity as a bulwark against the negativity, the endless differentiation, of the language (in which) one has become" (1994, 73).

[2.7] Here I use a Western fan fic, Maldoror's fan novel Freeport (2004–6), to look at how boys' love subjects may enter into language, and hence subjectivity, without necessarily entering into a sexual identity (note 5). I adopt the word divagation to describe temporal-spatial divagations in boys' love. Divagation recalls Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick's definition of queer as "recurring, eddying, troublant" (1993, xii). I will look at how queer divagations may help illuminate how relationships among characters are constructed. I consider two questions: How do bodily practices act on, and are acted on by, discourses in Freeport, in investing them with meaning? How does Maldoror use bodily and textual practices to inscribe power and resistance, and to create alternative temporalities in social space?

[2.8] Freeport is set in the distant future, after a war between Earth and its colonies in space. Although its characters are based on those in Gundam Wing, they are in an alternate universe in which how they act is the author's invention. Her story takes place on the shipbuilding colony Freeport, an immense hub-and-spoke structure in space, home to 130,000 citizens. In the eyes of the law-enforcement agent Wufei Chang, it is "the worst den of sin in the solar system" (chapter 1). Wufei works as an investigator for the Earth police agency Preventer. Under orders to capture a criminal who has fled to Freeport, Wufei has convinced his former teammate, Duo Maxwell, who is now a mechanic, smuggler, and Freeport resident, to sneak him into the colony.

[2.9] Wufei symbolizes the law, hunting predators who do political violence, no matter the cost. During his stay in Freeport, Wufei realizes to his horror that the ramshackle industrial city in which he is living with Duo is anarchist. It has no law, no police, and no government. Freeporters distrust outsiders, and they especially detest law-enforcement agents from Earth.

3. Entering into language

[3.1] According to Michel Foucault, subjectivity is "an effect of power" (1971, 30) and is exercised on the body: "Power relations can materially penetrate the body in depth, without depending even on the mediation of the subject's own representations" (1980, 186), and power "wrap[s] the sexual body in its embrace" (1978, 44). Wufei is denied the ability to publicly "enter into language." He is on probationary status, the means by which Duo was able to smuggle him into Freeport, and by custom, this demands his silence except when talking privately with Duo. The collar around Wufei's neck marks his body as one not allowed to make public representations. Wufei is, Duo tells him, "not a citizen…You're an extension of me…That's why you're not allowed to talk to anyone, or have a life or do anything without me. I'm your quarantine" (chapter 2).

[3.2] Discursive power may have wrapped part of Wufei's body, and the power of Freeport's unwritten rules binds him to Duo, but Maldoror shows him acting, using his body since he is deprived of language, to gradually attain subjective status. Power helps produce subjects, and it is expressed in part by discourses. Foucault characterized Western post-Enlightenment discourses around sex as multiple, increasing (1978, 30), demanding examination, and seeking causation (59), "an entire glittering sexual array" to produce truth at "a nearly fabulous price" (72). These discourses helped bring about an explosion in the number of perversions to be controlled as individuals' sexual practices were identified and cataloged as imagined types, one being the homosexual, which has been elaborated to such an extent as to become a "species" (43). In Foucault's view, confession became key to the transformation of sex into discourse and unlocking truth (61); it could exonerate, redeem, and purify (62).

[3.3] These observations underlie much of Western poststructuralist, feminist, and queer theory. Yet to a large extent in boys' love texts, it is as if these discourses do not exist. The textual practices in boys' love attempt to exclude them. Wufei does not confess to anything related to sex. He resists examination by dint of his muteness, and he is not (consciously) seeking exoneration or redemption. The truth Wufei seeks is the identification of a criminal, not that of his own erotic desires. He and Duo are not Foucauldian types to be categorized: Duo is nominally straight, married to a woman on another colony, and Wufei, though gay, does not express it as an identity. He contains expression of his erotic desires and suppresses the possibility of emotion leading to love, behavior that Duo mocks:

[3.4] "Chang Wufei sleeps around. I'm sorry, this completely changes my conception of the universe. Maybe even the law of physics."

[3.5] "I do not sleep around," Wufei corrected with dignity, not bothering to honor the rest of the comment with a reply. "I have friends—two, at this point in time—with whom I entertain sexual relations when I'm not on duty and we are available for each other…I choose them carefully," he continued sternly, "to make sure they are not likely to compromise themselves emotionally over a relationship, and of course I vet them through Preventer security."

[3.6] Duo's eyes had been getting progressively rounder. Finally he blinked and then thumped his fist against his chest. "Oh, the romance," he stated sardonically.

[3.7] Wufei gave him an ascetic look. "Romance is not something any of us are looking for." (chapter 25)

[3.8] Freeport citizens may or may not assume Wufei and Duo are erotically engaged, but no one seems interested in finding out how or why. Duo's friends and neighbors attribute no more meaning to his friendship with Wufei other than its potential to make Duo happy.

4. Abjection and body

[4.1] In theory about the body, Grosz posits that the developing subject must be interlocked with a signifying system (1990, 81); it becomes a subject only when it can signify its corporeality in the symbolic (85). It is in danger of losing materiality altogether to the abject: "The abject entices…the subject ever closer…It is an insistence on the subject's necessary relation to death…being the subject's recognition and refusal of its corporeality" (89). In the thinking of Julia Kristeva, the abject subject's rejection of others is a recognition of "the impossible [that] constitutes [his] very being" (Kristeva 1982, 4). It is a "violence of mourning" (15) brought about by what "disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules" (4). It is a state where laughter masks "a hatred that smiles, a passion that uses the body for barter instead of inflaming it" (4).

[4.2] The abject state is implicated in the formation of real-life subjects in Kristevan psychoanalysis. In fiction, abjection is a textual practice that employs bodily practices. In boys' love, the author is often emphasizing directly to the reader the bodily consequences should the subject not overcome the abject. In Freeport, Maldoror shows Wufei becoming aware of the enormity of what is at stake: his existence as subject, able to love and be loved. Wufei is in a state of literal mourning over the loss of his family, who were killed during the war, and at the government that Preventer serves having betrayed its goals by being complicit in the brutal exploitation of its citizens. Maldoror shows him fighting, from minor squabbles to physical confrontations, almost constantly with Duo, a violence of metaphorical mourning wherein Wufei bemoans both the "hellhole" that is Freeport and the proud anarchist his former wartime teammate has become. One of these arguments comes when he realizes how alien Freeport's system is to what he considers his core beliefs:

[4.3] Wufei was appalled, and not just as a representative of law and order. This went against so much he'd been taught and believed in. "I can't believe this obscenity works."

[4.4] "Define 'works.' Do we have a level of violence to rival most colonies? Sure. Is it dark, cold and stinky? Well, yeah. Do we get drifters and psychopaths and malcontents and rebels? Hell, we embrace 'em. Are we all one accident away from total disaster and a hullbreach? You betcha! Do we have kids with rickets, thieving meals, peddling drugs and living little better than rats like they still do in every slum today, even in the richest countries? No." (chapter 8)

[4.5] In this scene Wufei rebuts Duo's argument at great length, yet after several weeks of living with Duo on Freeport, he begins to grudgingly accept Duo's observations, keeping silent in the face of Duo's assertions such as, "A society with ghettos is at war. It's just not the kind of war that has tanks and Gundams" (chapter 15).

[4.6] Wufei had bartered with Duo to be allowed onto Freeport, offering him the chance of capturing a hit man named Carver. In this bargain, Wufei follows his habit of suppressing erotic passion. But that barrier begins gradually eroding after several weeks of sharing a small room on a common mission with a wartime comrade he trusts and by whose side he engages in life-or-death battles:

[4.7] Wufei realized he was staring at Duo's [sleeping] profile again. It was bathed in the glow of the laptop Wufei was supposed to be using to review news reports of recent disturbances throughout L3.

[4.8] [Duo] had a faith in himself, in the future, in this chaotic, violent colony, that…seemed to radiate from him, feeding his restless energy…And he had a fierce loyalty towards Freeport and the people he met and dealt with.

[4.9] That faith had been placed in Wufei as well. And here, tonight, in the glow of the laptop's screen—scrolling through riots where he should have been present, rather than rotting in Freeport—tonight, Wufei didn't feel worthy of it, and not only because his presence here was in part a sham. Wufei had no faith. He lived for Justice because it was his duty to the dead; he had faith in nothing and no one. (chapter 19)

[4.10] Wufei disturbs the system and the order, first on Earth by greatly overstepping his bounds as a police agent, then on Freeport where he kills someone in his few days there. He does not respect borders in either place. His smile masks a hatred toward anyone who might exploit the weak, including the government he had sworn to uphold. He is in many ways a precarious being. Yet as he gradually understands Duo's motivations for his anarchist beliefs, he begins to accept Duo's having them. Eventually Wufei begins to share some of them. As he sees more of Duo's personality, Wufei begins to think about his own and how it may hinder his relationship with Duo. Wufei begins to reciprocate the faith Duo has in him, and in so doing, he begins thinking of himself as able to have faith in others. He thus begins to overcome the abject.

5. Becoming subject

[5.1] The semiotic, in Elizabeth Grosz's view, is a sort of decentered libidinal organization (1989, xxi). In boys' love, it applies to the not-yet-subject—that is, someone who is not yet able to relate productively to others. This person must overcome the abject to do so. In contrast, the symbolic is the order of language and representation. Applying this conception to Freeport, we see Wufei striving to attain the symbolic.

[5.2] Wufei acts by distancing himself slowly and publicly from being an extension of Duo. He works to acquire agency. He helps his neighbors and others in the gritty industrial sector in which they live, and he acts to hunt, with Duo, the criminal Carver. Already physically far away from the Preventer agency, he further distances himself by neglecting to report to them, by no longer attempting to live by their regulations, by changing his appearance, loosing his hair from its ponytail, and by eventually severing ties. As he moves away from the language of Earth-based notions of policing and judicial procedure such as presumption of innocence and due process, he sheds his status as a law enforcer. Duo helps in this, acting to pull Wufei out of his shell, as if showing him that the symbolic order he had lived under is not merely inappropriate for Freeport, but also for Wufei himself as subject. Duo does this, in part, by continually making clear to Wufei that they can relate in ways other than as smuggler and cop. To this end, Duo maintains a constant barrage of erotically suggestive verbal interplay, teasing Wufei, trying to provoke him, incite him, into physical action. This, too, is a bodily practice.

[5.3] In Freeport, the symbolic is under pressure, and with it, major related elements, including time-space. The boundaries in boys' love, among its characters as well as the frame that surrounds its discursive field, tend to be approached in something other than a straight line of temporal progression. Grosz writes that "the boundary between…self and other…must not be defined as a limit to be transgressed so much as a boundary to be traversed" (1995, 131). Traverse is a word that admits of an oblique approach, a playing at the limits, and it carries a temporal resonance, not necessarily a binary crossing but continued crossings back and forth, that are, in boys' love, queer divagations along boundaries and between subject and object. Duo and Wufei, and many boys' love characters, act on desire by inciting one another to acts, resisting these acts, and inciting each other again in a process of approaching, retreating, and approaching again from another angle, the barriers preventing them from bonding.

[5.4] This is a type of play. Jane Gallop quotes from Roland Barthes's The Pleasure of the Text that pleasure "is a drift, something…that cannot be taken care of by any collectivity…the pleasure of the text is scandalous: not because it is immoral, but because it is atopic." To this Gallop adds, "'Atopic': strange word…not of a place, neither here nor there" (1988, 109). No fixity: a drift, a divagation. Mark Vicars and Kim Senior posit a definition for yamanashi, which above I defined as "no climax": "Like a day dream or the twilight between dream and sleep…where there is no need to 'climax' but it is possible to rest in perpetual abeyance…to pause, redirect, and relocate our imaginings to another moment" (Vicars and Senior 2010, 190).

[5.5] Grosz writes that boundaries are a product of passage: "It is movement that defines and constitutes boundaries" (1995, 131). If so, then the movement of bodies and bodily synecdoches—such as blood and semen—through space as characters come (in multiple senses) together, helps define boundaries in boys' love.

[5.6] Boys' love authors use both textual and bodily practices to traverse barriers. Maldoror brings Duo and Wufei to their first sexual experience together by associating sex with freedom and the absence of government-imposed rules. She emphasizes this with her setting, the sector in which they live having anarchist slogans painted in large letters on its interior walls. In addition to Duo's provoking Wufei verbally, he does so with his body. After a vicious fight with Carver and his gang, Duo and Wufei make their way back home, physically exhausted. As they walk, they argue over who had won their contest to kill more of Carver's men. It was a tie. Wufei says, "Then we're even," to which Duo responds, "First one back wins it then," and takes off running, with Wufei close behind:

[5.7] Wufei didn't lose sight of Duo as they ran past the writings high up on the sector wall, but he could see the huge letters as if they were printed in the air in front of him.

[5.8] "Only my freedom."

[5.9] His heart pounded as he chased the darting black shape, braid dancing like a war banner.

[5.10] "Do what you want if you think you've earned it."

[5.11] He could feel every inch of his body, the sensual trickles of sweat down his back, the unbound hair whipping his face, every nerve singing a fierce pagan hymn to the pleasure of having survived and paid in blood those who had tried to kill them.

[5.12] "Live now. Tomorrow we die."

[5.13] Duo slammed into [his] backyard door—he didn't have time for a breath, Wufei piled right into him.

[5.14] "I won!" Duo huffed.

[5.15] "Didn't." Words and gasps blended, melded with Duo's hurried breathing. "You cheated."

[5.16] Duo's hands were hard as they grabbed his arms, swung him around and pinned him against the door.

[5.17] "I won," Duo purred, and kissed him fiercely. (chapter 22)

[5.18] To which Maldoror adds, immediately after that last sentence, the voice now hers as the author: "Live now. Tomorrow we die." She is making a textual intervention, a textual practice to underscore the collapse of Wufei's symbolic. She is putting it in the past. She is freeing Wufei and Duo from the past and the future, suspending them only in the present, suspending time as they run through space, overcoming physical and metaphorical barriers in their path, their highly active bodies contrasted with the seemingly immutable slogans, outside of time. These slogans, too, are interventions in the text. Grosz writes that time inheres in space and objects (2005, 181), that it causes objects to exist (180). In other words, time causes subjects to become subjects. Time is also a force. In Freeport, subjective space is enclosed. Its subjects are on a colony, surrounded by the vacuum of outer space. Maldoror uses her locus to vector time, to concentrate it as urgency, to emphasize to Wufei that "tomorrow we die" and that therefore Wufei must live in the present.

6. Queer border dwellers

[6.1] According to Grosz, in Kristevan thinking, abjection "marks the threshold of the child's acquisition of language," in which the spaces between subject and object "need to be oppositionally coded for the child's…subjectivity to be definitely tied to the body's form and limits" (1990, 86). If abjection marks such a threshold, then boys' love authors such as Maldoror are intervening early in the formation of subject.

[6.2] A threshold is a type of border. It marks the passage from one space to another. It's a liminal place in which one typically does not linger. As one crosses a threshold, he or she leaves the past behind to enter a new space. The threshold prevents the now-past from entering the to-be present. It walls off the past; it's a refusal of the past, including past language. This may be so not only for subjects in fiction but also for real people. Thomas Piontek has called the sissy boy a "queer border dweller," one who has not yet acquired, who may never acquire, the accretions of masculinity that allow him to pass for straight (2006, 61). Piontek is following here the reasoning of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, who wrote that the "great advance in recent gay and lesbian thought" of theorizing "gender and sexuality as distinct…may leave the effeminate boy…in the position of the…haunting abject of gay thought itself" (1991, 20). Piontek reasons that the sissy boy "points toward alternatives to the binary thinking that has structured gay thought" (2006, 61).

[6.3] Piontek's queer border dwellers are at the threshold of the separation of sex and gender. It is this threshold that is portrayed in Freeport, and in much of boys' love. It is a threshold between semiosis and symbolic, the nonmasculine and the masculine, between being boys in love and entering into a sexual identity. It plays out in boys' love as Grosz hypothesizes that it may in real life. Judging by the boys' love stories I have read, their authors appear to make this threshold nonliminal; in their stories, it's as if this threshold is continuous. In so doing, they are refusing to separate sex and gender, refusing the advance identified by Sedgwick. However, they do show their subjects overcoming the abject. They do so in order to allow their subjects to enter into language, and thus to become productive subjects, able to desire and be desired by others.

7. Dedication

[7.1] Dedicated to the memory of Camilla Decarnin, my best friend and toughest editor. I miss her companionship very much.