1. Introduction

[1.1] The concept of virtual idols was first introduced in Japan in the 1980s. In the beginning, virtual idols were content-driven—mainly cartoon images linked with anime and games—and their creation methods were similar to those of animation (Yu and Geng 2020). For example, the "lovelive!" series, which is still very active, is a virtual idol group that uses ACG works and content as the main vehicle.

[1.2] In the twenty-first century, the development of computer technology resulted in the introduction of Hatsune Miku—a new type of technology-based virtual idol. Hatsune Miku was first designed and launched for the sale of VOCALOID, a second-generation voice synthesis technology software, and the company's original vision was to use virtual images to broaden its customer base and attract potential target audiences (Yu and Geng 2020). Virtual idols of this era rely more on audio synthesis technology and immature 3D modeling technology for presentation.

[1.3] On November 29, 2016, a new YouTube channel called A.I. Channel uploaded its first video, featuring a 3D-rendered animated girl who calls herself Kizuna AI and describes herself as an artificial intelligence. Kizuna is a unique content creator, a digital character that utilizes real people behind the scenes to do the voice acting and manipulation. With the creation of Kizuna, the development of virtual idols has entered a new paradigm (Turner 2022). The virtual idol is no longer a robot generated by a computer program that does not have emotions but has become an emerging product of the combination of real people and computer technology.

[1.4] Nowadays, virtual idols rely more on motion capture technology for virtual live streaming. Virtual live streaming refers to the replacement of live scenes and images with virtual scenes and real people, bringing a new audio and visual experience to the audience, while reducing the cost of building the original scenes. Motion capture technology uses a tracker to measure the position and orientation of an object in physical space and then records the information in a computer programming language. Gesture control technology is another key technology; using this technology, virtual idols can make more specific and complex gestures. These gestures can improve the interactive experience between the idol and the audience (Kong, Qi, and Zhao 2021). And the use of multiposition cameras can capture details of movement that are not easily observed by the human eye and can present a full range of the actors' movements. Virtual idols have their own virtual settings and content output, behind-the-scenes staff serve the virtual settings, and user-generated content (UGC) is able to participate in perfecting the virtual idol's persona (AiRui 2022).

[1.5] In December 2020, the five-member girl group A-SOUL used more mature technology, more diverse content forms, and interactive methods, quickly gaining much attention, soaring fan numbers, and strong fan loyalty (Wang 2022). A-SOUL is the product of a combination of the internet company Byte Dance and a traditional entertainment company Yue Hua; it has five members—Ava, Kira, Carol, Diana, and Eileen—each with a clear and different character to appeal to different audiences. Their group account has more than 400,000 followers on China's largest video site, Bilibili, and Diana has more than a million followers. Their enormous commercial value has earned them endorsements from a number of large corporations, including KFC and Geely.

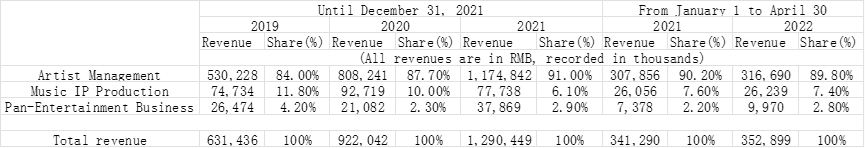

[1.6] The explosion of A-SOUL has driven many companies, including Tencent, Bilibili, and Kugou Music, to enter the industry, and various types of virtual idols have shown explosive growth since 2020. According to the prospectus provided by A-SOUL's parent company, Yue Hua Entertainment, the output of the company's pan-entertainment business has been increasing: "Our revenue generated from our pan-entertainment business increased from 21.1 million Yuan in 2020 to 37.9 million Yuan in 2021, mainly due to revenue generated from the commercial development of our virtual artist group A-SOUL (to be launched in late 2020). Revenue generated from the pan-entertainment business increased from 7.4 million Yuan for the four months ended April 30, 2021 to 10.0 million Yuan for the four months ended April 30, 2022, mainly due to the increase in revenue generated from A-SOUL, a virtual artist group" (table 1). As of 2022, China's virtual idol core market size is expected to reach 1.3 billion Yuan (approximately 180 million USD) (AiRui 2022).

Table 1. A-SOUL prospectus.

[1.7] The explosion of interest in virtual idols is closely linked to the pandemic, which resulted in the suspension of many off-line entertainment and socializing activities, with people feeling enclosed in their homes and needing to find an outlet for entertainment and emotional outbursts on the internet. Virtual idols can provide emotional value while using user-generated content (UGC) to keep the audience engaged. At the same time, large internet companies are using their strengths in technology and marketing to intervene in the pan-entertainment industry and satisfy the young male consumer base that has been neglected by the entertainment industry.

2.Virtual idol: A new form of risk avoidance

[2.1] Celebrity culture is under fire like never before in China. Online lists on Weibo that rank celebrities by popularity have been banned. Fan club culture is being targeted by a government that perceives it as harmful to the mental health of China's young people (Mao 2021). At the same time, China has also imposed strict bans on artists who have broken the law or are the subject of scandal, such as Fan Bingbing, who has not appeared in any domestic movies since she was punished for tax evasion. The Chinese government's ban on such celebrities can cause investors to lose a lot of their investments. Because of this, many investors started to invest in virtual idols with lower risk and stable returns.

[2.2] Virtual idols still require real people to perform behind the screen (中の人: person inside). It is always the virtual image that is followed in the process of communication rather than the person inside. This also means that virtual idols will never have the problem of collapsing personas. The personality traits of virtual idols can be edited to perfectly match the needs of the public. Once the person inside does not meet this demand anymore, the company just needs to replace them, and viewers in front of the screen will not feel that the virtual idol's persona has changed. On the other hand, some small companies, who do not invest much in the image of their virtual idols, can choose to simply announce the "graduation" (stopping all activities and cancelling the account) of the virtual idol, and then let the person inside change to a new image and go live again. Because of the excessively low cost of breaking the law, many unknown actors who have not yet ended their agency contracts but cannot get a chance to perform on stage have entered the industry at the risk of breaking their contracts. This is because it is difficult to define under China's current law whether a virtual idol's character belongs to an actor or a voice actor or simply a technical participant in motion capture.

3. Virtual idol: A new fan–idol relationship

[3.1] The fan–idol relationship that is now popular in China originated from the spread of the Korean Wave in China. As a result, the entire fan community has inevitably become Koreanized. The Chinese fan community is not homogenous. Fans are stratified based on their attachments to their idols. Core fans often hold devout feelings for their idols, have greater emotional and time investment, and spare no effort in supporting the idol's products. Ordinary fans are more detached and invest in their idols in line with their personal limits. "Passerby fans" are even less committed. They selectively pay for an idol's products only to fulfill personal needs (Liao, Koo, and Rojas 2022).

[3.2] The basis of this fan–idol relationship is the intimacy that fans fantasize about. In religious and fan circles, the desire for intimacy drives individuals to act in ways that transcend the self in order to seek greater communication with the object of their admiration, to seek out celebrity perceptions, and to fantasize about further intimacy (Min, Jin, and Han 2018). Fans engage more with their idol as a fantasy object of desire. This emotional involvement is asymmetrical. At the same time, there is also a productive attachment in the traditional fan–idol relationship, where fans get emotional compensation by voting for their idols and topping the charts. Many fans like to call their idols "sons" or "daughters." The emotional attachment, which is characterized by maternity, also strengthens the identity among fans. In this game, fans have successfully completed the "making of gods," making their favorite idols into national idols. In other words, the starting point of the fan community's action is to protect the idol within the framework of productive attachment.

[3.3] Such a fan–idol relationship is unsustainable. Because traditional idols can use the media to try to build a perfect persona, the idols are deified by their company and fans. However, the idol that fans follow cannot be perfect, being a real person. Idols can have romantic scandals or moral turpitude, which are unacceptable for fans. The attachment-based fan groups cannot accept that their idols have their own lovers in reality and may abuse their colleagues who work with them. Everything they love about their idols is based on the fact that their idols are gods and not people.

[3.4] East Asian culture is by nature ascetic and introverted. In real life, everyone lives by a strict set of rituals that suppress individuality. Many people project their suppressed instincts onto these unattainable idols. The idols produced in this culture have to suppress their individuality and follow the company's schedule to the letter in an effort to cater to this intimate construct. For example, the company will make an idol open gifts sent to him by fans live on the internet on his birthday and thank them one by one, or utilize software like Bubble to have private chats with paying fans and listen to them share their personal lives. This fan–idol relationship, which is similar to a boyfriend–girlfriend relationship, leads to a mass exodus of fans in the event of a scandal involving the idols themselves, especially in the case of romantic scandals. Because of this "intense personalization," fans believe that they have a special bond with their favorite idols (Zhang 2022).

[3.5] Virtual idols, on the other hand, see fan relationships as a kind of friendship and build a bilateral attachment with their fans. Virtual idols often acquiesce to, or even encourage, fans to participate in their live streaming work. Virtual idols allow fans to create user-generated content (UGC), such as second edits of live streaming, or allow fans to make short videos with the idol's virtual image and watch them during the live stream. At the same time, the virtual idol will act like a mailbox, accepting anonymous submissions from fans, or collaborate with fans in online games. This unique pattern of getting along is more like an interaction between friends.

[3.6] For example, A-SOUL is very receptive to UGC; whether it's a secondary adaptation of a song (figure 1), making a game, or writing some little essay expressing their love, A-SOUL will share it with everyone on stream, as well as participate in it themselves, for example, to grade those essays. These essays often have strong meme attributes, so they spread very quickly, and some memes have even broken through the A-SOUL subculture and become well-known memes on the internet, which has largely contributed to the spread of A-SOUL's popularity. This is not possible in a traditional fan–idol relationship.

Figure 1. UGC song adaptation, incorporating the popular memes of the Chinese internet at that time. A-SOUL Super Sensitive Remix Super Truck, uploaded to Bilibili on August 17, 2021.

[3.7] The relationship between virtual idols and fans places more emphasis on sincerity. A sense of companionship and equality is at the core of the interaction. To a certain extent, this virtual idol has a lot of similarities with the Japanese civilian idols. They both advocate the common growth of fans and idols, using sincerity to influence fans. Virtual idols as a cultural product sell imagination through role-playing and storytelling, to build a personality that does not exist in reality and to satisfy the imagination of fans. For example, A-SOUL shed tears because a fan has depression, advise fans to exercise, and open a live broadcast in the middle of the night to chat with fans. This kind of interaction gives fans a sense of belonging to a home and gives them strength. The fans also keep giving A-SOUL kind encouragement to make them perform better in their performances.

[3.8] In the traditional fan–idol relationship, the audience perceives very limited real emotion from the idol. This is because idols have very strict speech templates and interaction rules. But virtual idols can present more, and even though this is part of the performance, it can give the audience a more intimate feeling. When virtual idols talk about their lives, that is often the moment when the audience reacts most intensely. In the traditional fan–idol relationship, the only thing an idol can present is front stage content, attracting fans through performances. The daily content is private. This clear distinction between the front stage and the backstage makes it difficult for fans to get to know the true side of the idol (Zhang 2022). Virtual idols seem to have broken down this barrier, with viewers seeing the live broadcast room as the idol's own room, and the idols share some of their daily content during the live stream and even release their dinner today on social media platforms; for example, a virtual idol posted her dinner on the social media platform with the comment, "If dumplings could talk what would it say?" (figure 2). Even though these scenes are selected and even fictionalized, the viewer builds a touchable image in their own mind.

Figure 2. Screenshot of dinner posted by a virtual idol on Weibo on July 14, 2023.

4. Virtual idol: A new type of internet community

[4.1] In addition to more genuine fan–idol relationships, another reason why virtual idols have been able to grow in China is the social backlash caused by the abuse of cancel culture by traditional idol fan groups. The strict hierarchy of traditional fan groups allows them to quickly cancel through division of labor. Cancel culture is being abused more as a form of disempowerment.

[4.2] A good example is the appearance of a homoerotic novel about Xiao Zhan, a well-known Chinese icon, on the nonprofit website Archive of Our Own (AO3) (https://archiveofourown.org/). A fan posted the novel to the Chinese social media Weibo after re-editing it. Because of Xiao's huge influence, the re-edited novel quickly spread across the internet. The novel portrays Xiao as a gay man. But many fans didn't like the premise. The fans that don't like this novel asked distributors and the author to delete it. They described the author and those who were still spreading the re-edited novel on the internet or reporting about it as antifans and used the reporting mechanism of social media platforms to cancel the posters under the pretext that they were spreading pornographic content. Many people's social media accounts were blocked as a result. In addition, many of the people who posted the re-edited novel are also members of other subculture communities in addition to being fans of Xiao. These subculture communities have been subjected to massive reporting and hacking.

[4.3] However, because the homoerotic novel about Xiao Zhan still existed on AO3, many people continued to re-edit and post out of frustration with the culture of cancellation. After fans unsuccessfully protested several times to the AO3 platform to remove the novel, they reported the platform to the government. Eventually, the government made AO3 inaccessible in mainland China. And throughout the whole process, Xiao did not speak out but simply let his fans go about destroying the future of a platform that encourages diversity in China. This cancellation in order to protect the idol has annoyed more people. Such large-scale actions similar to cyberbullying happen almost every day on the Chinese internet. This has seriously affected the cyber life of ordinary netizens and as a result has created a great distaste for this traditional idol–fan relationship.

[4.4] Meanwhile, the virtual idol community is built by groups that resent this pathological cancel culture. On the one hand, they resist the strict stratification of fans in traditional fan communities. Without the stratification of fans, there is no leader, and without a leader, many cancellation activities cannot be organized at all, and spontaneous boycotts often cannot be expanded due to disagreement within the fan community. In addition, there is a consensus within the fan base that "I don't care who you are, I don't care who I am, and with the cover of an anonymous social account, I can say anything I want and no one can question me" (Wang 2022). It is difficult to form a consensus within a fan base when there is such a diversity of expression in the fan community that it is difficult to attack and cancel other fan groups.

5. Problem of development

[5.1] One problem this decentralized fan community can lead to is a breach of personal privacy. Decentralization means that everyone can be a leader, and what they can do is out of control. The special nature of virtual idols has led to their information being kept secret by the company, which has led to some crazy fans learning special ways to discover the personal privacy of virtual idols and harass the 中の人 off-line. Meanwhile, they can skillfully apply these tactics to online violence against other online users. Their online identities shield their real identities: they dress up in virtual idol themes that can be seen by others or change their names and profile photos to relate to their favorite or disliked virtual idols. This has a serious impact on how virtual idols are perceived by the general public, which in turn affects the growth of the fan base.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] Technology has changed the way idols are created. Idols are no longer the monopoly of real people. Virtual idols have also changed people's perception of the fan–idol relationship, which is never about fans giving without expecting something in return but is a two-way, mutually beneficial relationship.

[6.2] The rise in popularity of virtual idols can be described as the increasing personification of technological objects. It is difficult to define whether virtual idols belong to objects or real people. But the popularity of virtual idols shows the public's admiration for technology, and in the production and consumption of virtual idols, they construct a new myth.

[6.3] But at the same time, the popularity of virtual idols among young people also indicates that a new mode of communication is gaining popularity among the youth. Young people prefer this mode of equal communication. Because of the popularity of the internet, young people are becoming more and more closed to themselves, so they need someone to listen to them and talk about their thoughts, and they need a sense of companionship. This kind of communication mode can be loved by young people.