1. Introduction

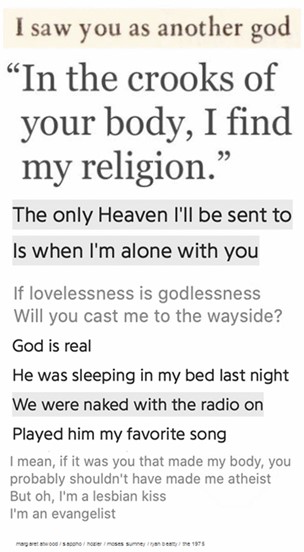

[1.1] In this article I introduce the emergent phenomenon of "parallel posts," a form of literary meme on microblogging website Tumblr. Parallel posts—also known as web weaving (note 1)—are collages of decontextualized quotes responding to the same theme, often taken from contrasting sources across mediums and across "brows" of culture. Their thematic cohesion and formal structure vary: some read as centos, self-contained poems made of lines from other poems; some as collages; some as memoirs; and others as essays. There are multiple common formats, the most prevalent being a sequential collage of photographed or screenshot quotes (figure 1). While parallel posts initially featured writing alone, images and screenshots were incorporated soon after the form's genesis. Parallel posts emerged from the intersection of bookish and fandom communities now known as Dark Academia on Tumblr in approximately 2018. Since then, parallel posts have gone from a niche trend to one of the Top Meme formats on Tumblr, ranking thirty-sixth in 2020 and eighth in 2021 (Fandometrics 2020; 2021) (note 2).

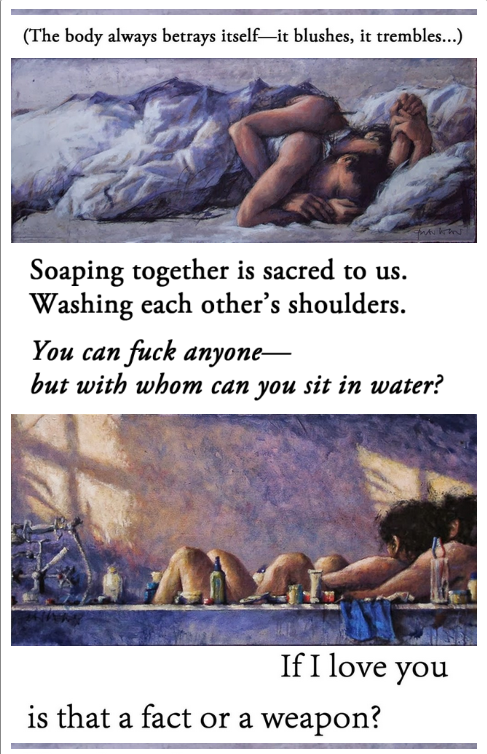

Figure 1. A collaged parallel post. Adair. 2020.

[1.2] Seeing parallel posts alongside each other in such hashtag threads as #parallels and #web weaving, they seem distinctive for their shared themes and emotional valence: they are principally concerned with love, time, monstrosity, and gendered and queer experience. They are noteworthy on Tumblr for heroing such literary elites as Anne Carson, Louise Glück, Richard Siken, and Ocean Vuong, but they draw just as much from television shows Supernatural and Hannibal and pop musicians Hozier and Mitski. The widespread practice of combining canonical literary works with other forms of media, including what some consider lowbrow, is a method of communally creating a miniature literary canon of texts that resonate with users, regardless of their origin or standing off Tumblr. By showing equivalent sentiment between texts, creators both highlight the artificiality of cultural prestige and demonstrate the worth of manifold media to be archived.

[1.3] For individual users, parallel posts act as technologies of the self (Foucault 1988) or tools of self-reflection, self-performance, and self-transformation. Users draw quotes from many different parts of their lives—poetry, street signs, or their own journals—to document and process the media landscape around them. In this, parallel posts resemble commonplace books, manuscripts or journals kept to collect quotes under themed headings. As Evan Hayles Gledhill (2018) argues, Tumblr itself has always been much like a commonplace book or sentiment album—a later and more artistic form of the commonplace book. Gledhill posits that while technologies have changed, traditions of textual subversion and transformation have not; curators of albums and blogs alike transform cultural material toward self-expression and creation of new, collaged media. Both album and blog curation are thus technologies of the self. Kate Eichhorn (2008) theorizes the link between commonplace books and digital content curation, specifically in the form of literary blogs, as "archival genres" or forms of curation that are "plotless," "meandering," and "accumulative" (7). Archival genres play at the cusp of the social through their pronounced transtextuality and their uses as self-acculturation tools; they are networked technologies of the self, the personal and public intertwining. Each post represents one person's media reception, filtered through their blog's personal framing of tags, titles, and narrative, which is then shared with and by others. Each user adds new threads of media to draw on and new ways of connecting texts, beginning the cycle again and cumulatively forming a socioliterary culture.

[1.4] Much as Lockridge (2004) argues that commonplace books are "the ultimate source for the study of reading, the book, and identity" (337), I argue that parallel posts are an acute symptom of, and point of insight into, broader digital literary culture: they welcome the abundance and overwhelm that define hyperconnected online life by drawing from many sources, and, uniquely, they temper that abundance by fragmenting texts and further connecting them to others. Reiteration and recirculation of fragments, born of rumination and for the most part lacking the curator's personal voice, is a direct contradiction of abundance-focused and personality-driven mainstream bookishness (see Birke and Fehrle 2018; Birke 2021), but it is wholly resonant with the compilation of commonplace books. I suggest that parallel posts are a resurgence of commonplacing born from the overlap between digital bookishness and Tumblr's fandom culture.

[1.5] Parallel posts are a counterpoint manifestation of bookishness, or the digital performance of self as closely affiliated to books and reading, and a large part of their counterpoint nature is that they are themselves transformative work; texts are treated as archives to draw from in creating new work, and users transform each text quoted through its cutting and recontextualization. While parallel posts are not automatically recognizable as fan work, lacking a central text, when taken en masse, they clearly resemble a fandom in their recurrent texts, themes, ideology, and community norms; and, as individual artifacts, they resemble other fannish practices that use transtextuality to enrich or shape new work, such as fan vids and song fics. Beyond generic norms, parallel posts are now a common format used in fandoms; across fandom and more general blogging, transtextuality is used to amplify sentiment, elucidate relationships, build upon subtext, or act as meta-analysis, with each quote providing an analytical frame through which to view a fan text. Where the sharing of single quotes is a common sign of bookishness online, unlinked to fandom, parallel posts' formative traits of rumination, reflection, and compilation come from Tumblr's affordances as a hub of transformative work and culture. I suggest that parallel posts are a crystallization of Tumblr itself; they are a climactic form of intertwining fandom and bookish cultures, capturing Tumblr's multimodality, affective intensity, and role as a technology of the self for users. As commonplace books give rare insight into the impact of media on everyday people through history in contrast to the literary canon we see now, parallel posts illustrate the value Tumblr users see in media, untethered to specific fandoms or spheres of cultural capital. On Tumblr, all media is both tool and inventory in a constant state of transformative, fannish, and personal transtextuality.

[1.6] I frame this article around the work of two case study users who make parallel posts, named as Adair and Marlowe. These studies were carried out with ethics clearance from the University of New South Wales' Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel. I identified users who had made multiple parallel posts that were representative of parallel posts' generic norms through the public #web weaving hashtag thread. I narrowed my search to those who had made parallel posts for over a year. I contacted prospective case studies via the fan mail or message features on their blogs. Users gave consent via plain-language information sheets and confirmed that they are over eighteen. I surveyed their posting archives to acquire an overview of their use of Tumblr, then closely analyzed tag searches relating to parallel posts and bookishness. I removed all identifying information from stored data and anonymized them. I excluded for analysis any posts featuring "do not reblog/do not interact" statements. I chose to discuss these two case study users as they have engaged explicitly with ideas of bookishness and Dark Academia and have made various kinds of parallel posts.

[1.7] I begin by introducing the cultural context from which parallel posts emerged and theories of technologies of the self. I analyze several of Adair's and Marlowe's parallel posts, establishing the generic norms of parallel posts and their roles in their curators' lives. I discuss Adair's and Marlowe's blogging practices in the context of bookishness and "digital hyperconnectivity" (Brubaker 2020) and posit that parallel posts are both reflections and rejections of current digital literary culture. I conclude by discussing the role parallel posts play in analyzing Tumblr and the uses of literature in the digital age.

2. The cultural context of parallel posts

[2.1] As the commonplace book fell from standard use in the twentieth century, the digital rose, facilitating collage, remix, and transformation as widespread modes of media engagement (e.g., Eichhorn 2008; Jenkins 2015; Fathallah 2020). De Kosnik (2016) argues that audiences regard media as an archive from which they can redeploy content for their own creations, which has facilitated a democratization of cultural memory; audiences are no longer "consumers" but "users" of culture (277). Fandom is an intensified iteration of media use, and as Stein (2017) argues, Tumblr's affordances centrally encourage "return, recirculation, and transformative reworking" (87); Tumblr thus intensifies both archival and transformative impulses as found in fandom. The democratization and use of culture by audiences is typified in parallel posts' form and in their self-created, subcultural literary canon.

[2.2] Beyond cultural norms, I suggest that parallel posts are a descendent of "moodboards," collections of images that revolve around a specific character, concept, or visual aesthetic (see also Stein 2017). Moodboards have been shared across multiple platforms, markedly Pinterest and Instagram. They were initially shared to Tumblr in the early 2010s, spreading from fandom to broader aesthetic blogs. They have featured as a Top Meme format in Tumblr's content review, Fandometrics, since 2016, when Top Memes were first recorded (Fandometrics n.d.). Moodboards' collaged appearance and thematic cohesion are mirrored in parallel posts—indeed, many users tag image-based curations as both parallel posts and moodboards. While a lineage of moodboards to parallel posts is—as far as I can tell—impossible to prove, I suggest that the parallel post's quick incorporation into Tumblr's culture occurred because moodboards or themed collage was already so prevalent.

[2.3] Parallel posts' ethos, pathos, and media canon have their roots in the fandom-cum-subculture Dark Academia, an aestheticization of education and literature taken broadly. Dark Academia unites sundry content in a frame of sandstone universities, Gothicism, and melancholia. It emerged on Tumblr in 2014 from the intersection of queer, bookish communities and fandom for campus novels and films, markedly Donna Tartt's 1992 The Secret History, ML Rio's 2017 If We Were Villains, and the 1989 film Dead Poets Society. These campus-specific texts were joined by the writings of Anne Carson, Richard Siken, and Ocean Vuong. These works have deeply influenced Dark Academia's development in themes, styles, and ideology, an influence that carries on into parallel posts. Dark Academia rose to global prominence in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic as a response to online learning and developed into a fashion and design trend and publishing category (Adriaansen 2022; Murray 2023). On Tumblr, Dark Academia has become a cultural trend that envelops multiple fandoms alongside aesthetic and community norms, much like the behemothic SuperWhoLock dominated Tumblr in the early- to mid-2010s.

[2.4] Dark Academia is a transformative extension of bookishness, or a self-conception grounded in "one's love of and deep involvement with books and book-related culture and objects" (Birke and Fehrle 2018, 74). Birke and Fehrle argue that digital bookishness creates a knowledge culture that emphasizes self-cultivation and community "in direct opposition to formal literary education" and to the "gatekeeping" of literary knowledge (77). Dark Academia complicates conventional bookishness's relationship with cultural capital with its emphasis on formal education and elite aesthetics, simultaneously staking claim to high culture and democratized cultural authority. As with bookishness broadly, Dark Academia raises issues of race and representation, intensified beyond the norm by its fetishization of European classical education. While users across platforms have attempted to diversify Dark Academia's visual aesthetics, educational ideology, and most-quoted authors, this has had limited effect; and as Adriaansen (2022) argues, even when "representation" is achieved, it is representation in a white and Eurocentric "cultural and intellectual canon," within set "aesthetic and normative boundaries" (9).

[2.5] The parallel post format emerged alongside Dark Academia, and while it is now used in different communities, toward different goals, its Dark Academic roots remain: it evidences an aestheticized interest in literature; often retains Dark Academia's Romantic, melancholic voice; and continues to use Dark Academia's canon of texts—and with them, Dark Academia's whiteness and Eurocentrism. More subtly, the prevalence of users tagging their parallel posts with terms such as #dark academia, #poetry, #quotes, and #books demonstrates that users view parallel posts as linked to bookishness, often regardless of content. Such tags create a pseudocommunity around the ideas of books and poetry—they represent cultural values and aesthetic preferences rather than literal subjects (see Birke 2021). Discussing Dark Academia as a sign that "the world of books and literary culture is […] at every turn intermeshed with digital media," Simone Murray (2023) calls for a new era of literary research that embraces "what is fascinating and transformational" in this era: "the fusion of print and digital media into a complex, hybridized, cross-platform ecosystem" (362). This article is one small step in the study of parallel posts, and it is a step toward Murray's vision of research into the uses of literature in the digital age, especially in overlap with transformative culture—whether in forms easily recognizable as fandom or those that are more mundane or diffuse. Dark Academia and parallel posts are interconnected parts of a flux in the relationship between literature and digital media—they are transtextual, transmedial, and grounded in both fandom and individual identity.

3. Technologies of the self

[3.1] While parallel posts may seem novel in their ruminative, affective form of content curation, similar phenomena have been theorized regarding both fandom and commonplace books. Here, I unite these theories under Foucault's (1983) theorization of technologies of the self and Eichhorn's (2008) theorization of archival genres.

[3.2] Foucault (1983) argues that in the hupomnemata, a Grecian antecedent of the commonplace book (Allan 2011), a state of self-knowledge and self-discipline was achieved through written reflection on others' knowledge—in other words, the collection of quotes. In the hupomnemata, it was insignificant whether a curator understood a whole text when quoting it; their personal reflection and linking of content was what allowed self-enrichment. External fragments were organized with internal logic to create a new whole, a chorus of disparate voices in the curator's "tissue and blood" (n.p.). This aligns with Foucault's later (1988) theory of "technologies of the self," or practices of active self-transformation. In the digital age, we are "hyperconnected" and "hypersaturated" with one another and with content (Brubaker 2020, 775). We are perpetually shown "inexhaustible storehouse of 'possible selves'" (775) in content to emulate or absorb; thus, to actively curate content is a vital technology of the self: processing overwhelming abundance, navigating the social realm, and creating artworks of the self (Jenkins 2015; Rettberg 2014). Tumblr's founder, David Karp, envisioned Tumblr as a space for creators, but as time passed, he emphasized curation, "a new, more accessible way to express yourself"; he considered Tumblr "a space you could really create […] an identity that you're really, truly proud of" via curation (in Tiidenberg, Hendry, and Abidin 2021, 6). McCracken and colleagues (2020) argue that Tumblr emphasizes "content over particular individuals" (24); people are most often perceived ephemerally, in reblogged (contrary to original) posts—on Tumblr, the self is found, harvested, created, and shared through fragments. From commonplace books to Tumblr, curation acts as a transformation not only of text but also of the self: the curator processes, performs, and organizes their lived experience, creating a new whole rendered on the page or screen.

[3.3] Parallel posts are an intensified exercise of self-curation; thus, any study of them must be grounded in what role they play in the life of individuals. Though observers witness curated content as finished products, a Tumblr user is perpetually creating a living archive in which parallel posts are only one part. Eichhorn (2008) argues that archival genres facilitate "dwelling" within texts: through meditative curation, a metaphorical space is made on page or screen for the curator to reflect on and sustain their experience of reading. Dwelling has been expressed variously across book history and fan studies—markedly by Lynch (2018), who posits the commonplace book's power is "pleasures of discontinuity and anachrony" (107), and De Kosnik (2016), who argues that fandom itself is a "resistant temporality" (158) in which creating and consuming fan works are "acts of remembrance" (29). I suggest that these theories refer to the same phenomenon: a slowed or stilted experience of time facilitated by rumination, repetition, and reflection through content curation, in a mode intimate to the self. It is this that drives parallel posts.

4. You're in a car with Richard Siken

[4.1] I turn to case study users Adair and Marlowe. The insight into a broad trend that individual case studies provide is limited, but as De Kosnik (2016) argues, while community and mass adaptation are essential to the perseverance of a form, most transformative acts are those of individuals—this is equally true of fandom, commonplace books, and parallel posts. In the work of these two users, we can see the diverse forms and functions not just of parallel posts but of Tumblr and technologies of the self more broadly. Marlowe blogs in an outward-oriented fashion and has created a strict order in the way she blogs; she uses bookishness and parallel posts as staples of her blogging and a frame within which she can express the ebbs and flows of her interests. Adair's blogging is oft changing, and their use of parallel posts has shifted as fluidly as their blogging has. Where Marlowe demonstrates Tumblr's bookishness as a whole and constant artifact, Adair shows bookishness in flashes, interwoven with other subcultures and uses of Tumblr (note 3).

[4.2] I here evidence Adair's and Marlowe's evolving, active uses of the parallel post form toward different ends, demonstrating its role as a technology of the self and mode of transformative work. I further discuss the users' tagging systems; tags are the organizing principle of Tumblr, both internal to each user's blog and on a broad scale—as Stein (2017) argues, amid Tumblr's central modes of "duplication" and "reiteration," tags perform "affective, analytic, [and] interpretive" roles (90), simultaneously adding to the abundance of content and creating order from chaos. Users establish their voice and priorities via tagging, much like curators made their commonplace books distinctive resources via indexing. Parallel posts have become prominent due to the use of shared hashtags such as #parallels, #web weaving, and #poetry, but individuals often tag their posts in personal and complex ways that are legible only when looking at their blogs as unified wholes. The specificity of a user's tags creates a semiprivate sphere of discourse; their followers (or others viewing their blog as a whole) are a closed audience to the way a user interprets and arranges information over time. While the content of each post could be reblogged, the framing and significance of that content to the user remains private, contained in their tags.

[4.3] As Adair and Marlowe have created many parallel posts, I have chosen a cursory starting point for my analysis—posts that use the work of Richard Siken, so-called poet laureate of fan fiction (Carlson 2015, n.p), and one of parallel posts' most popular authors. Siken rose to fame for his first collection, Crush (2005), in the Supernatural fandom; excerpts from Crush were used as epigraphs and titles to thousands of works of fan fiction, and fans theorized that Crush was Supernatural fan fiction in itself (Carlson 2015). Siken's popularity spread from Supernatural fandom to fandom at large, and then to Dark Academia. His work was among the first to be used in parallel posts, and his prevalence remains. The appeals of his work are myriad, but perhaps the most relevant to fandom are his representations of male/male love, portrayal of tragedy, and intricate free verse.

[4.4] Adair is a young adult university student from the United States of America. They have moved through many fandoms and interests over four years on the site, but literature, classical reception, and Siken's work are recurring themes. Adair's impact on Tumblr's poetic culture has been substantial in the poets they have shared and in their normalization of an analytical and melancholic mode of discourse aligned with Dark Academia (jokingly dubbed "role-playing as a literary theorist"), with an especial focus on body horror. Adair's taste in media is multifaceted and unpinned from strict ideas of cultural capital; they curate vastly differing content under the same tags and the same modes of affective and critical engagement.

[4.5] Much of Adair's renown on Tumblr is due to their complex tagging system (figure 2). Adair's tag directory acts as an archive of their thought processes; they catalogue content in accordance with their values and interests—from references to biology, ballet, and critical theory to quotes from poems. This is a common practice, though the extent of Adair's tagging is unusual. Each tag is a transtextual, fragmentary whole. Adair is further inclined to treat most communication as an opportunity for transtextuality; they respond to asks and hold conversations with other users via quotes and often contribute to others' parallel posts.

Figure 2. Part of Adair's tag directory. Adair 2022.

[4.6] Adair's first parallel post featuring Siken was in the "When/And" format. When/And posts begin with "when [author] said [quote]." Related quotes are connected with "and when [author] said." These posts function as run-on sentences, often erasing a quote's original formatting and cutting or changing words for grammatical consistency. The omission of line breaks and speech tags creates a sense of ruminative intensity, building with each quote. These posts often become dialogic, with other users adding quotes through a linking "and when"; thus, different versions circulate in tandem. Adair made this When/And post, initially without Siken's work:

[4.7] when emily brontë said "he's more myself than i am" and when hozier said "i'm almost me again, she's almost you" and when conan gray said "i know in your head / you see me instead / cause he looks a lot like i did back then"

[4.8] The Brontë quote implies such an intimate knowledge that one loses themselves to another; the Hozier and Gray quotes imply a lover imagining an ex-lover when with someone new. As a whole, the post explores blurred boundaries of intimacy, remembrance, and imagining. The authors vary in prevalence on Tumblr; Emily Brontë is relatively well known, Hozier is extremely popular, and Conan Gray is unusual. By incorporating a range of prevalence in authors chosen and tagging the post with common terms (e.g., #literature quotes, #web weaving), Adair simultaneously demonstrates their fluency in the preexisting norms of the genre and their own novelty as a creator, binding old and new. Months later, Adair reblogged the post from themselves adding "and when richard siken said; sometimes you get so close to someone you end up on the other side of them'" from "Snow and Dirty Rain," the final poem in Crush. This closely parallels the Brontë quote, intimacy collapsing the gaps between self and other. Adair's seamless continuation of this post shows the stickiness of the When/And form; in its very structure, it invites continuation; it can be an eternal work in progress.

[4.9] Interestingly, the day before adding the Siken quote to their post, Adair had shared another collaged post—if not a parallel post in itself—showing lines from "Snow and Dirty Rain" imposed over images of Supernatural's Dean Winchester and Castiel (figure 3). It is tagged similarly to Adair's other parallel posts but for the addition of fandom-specific tags; they make no hard boundary between literary and fandom work—the resource of Siken's work remains the same.

Figure 3. Adair's Supernatural edit.

[4.10] Adair's early parallel posts were conventional in themes, texts, and appearance. Over time, they became more unconventional and exploratory, using more images, scientific texts, and personal messages. Adair's newer parallel posts are often tagged as personal content rather than being related to literature or specific texts. Adair has used the form when entering new fandoms, but these posts are not outwardly oriented through tags—they too act as personal exploration. Some of their parallel posts seem academic in nature; in the tags of a parallel post, "THE SEMIO(P)TICS OF MIMESIS," they said "#thinking about it! […] all i can do is #bonk my head on the perimeter of this circle & hope to get a glimpse thru a crack in the bricks"; the post's creation was a part of Adair's thought process on a complex topic, reflecting Eichhorn's (2008) framing of archival genres as "straddl[ing] autobiography and critical writing" (7). More exploratory examples of their parallel posts include a cento "for castiel supernatural" intertwining images of The James Webb Space Telescope, pop lyrics, and a historical diary. Some of their posts have developed into parallels rather than being formed whole; markedly, they posted an article on caterpillars turning into butterflies, captioned with "this made me cry." They noted in the tags that they had been listening to the Squalloscope song "Caterpillars," then reflected on experiencing a severe injury after many years as a dancer. Adair reblogged the post from themselves four times, each time adding quotes about caterpillars' decay and transformation; they tagged these reblogs as parallel posts. Adding quotes seemed to be a natural progression of Adair's response to the article; they automatically referred to the song "Caterpillars" when articulating their personal life, and the associative map of ideas relating to caterpillars became more personal and intricate with each quote. As much as a rumination on caterpillars, the post became a work of transition—a bildungsroman of one's body, mapped through the work of others. Several users added further quotes, which Adair reblogged excitedly; though the post was personal, they welcomed the additions a social context allowed.

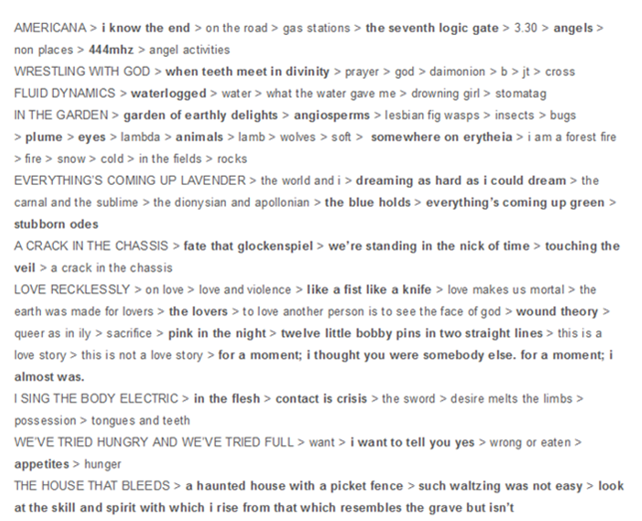

[4.11] Adair's parallel posts have changed in orientation and content over time, but Adair's experimentation with the form, archiving their media engagement as a meaning-making and sense-making practice, has not; figure 4 shows a recent parallel post using Richard Siken's work alongside scientific text. Adair ruminates and develops their thoughts through parallel posts, demonstrating the form's archetypal nature as a technology of the self.

Figure 4. A recent parallel post by Adair using Richard Siken's work. Adair 2023.

[4.12] Marlowe is an Armenian young adult and an extremely influential blogger in Dark Academia and broadly bookish Tumblr. Having begun fandom blogging in 2015, she refashioned her blog around Dark Academia in 2020. She shares parallel posts frequently, most of which garner thousands or tens of thousands of notes. She spearheaded several literary trends on Tumblr, such as sharing quotes featuring the names of months on the first day of each month and sharing the letters and diaries of Franz Kafka. Marlowe does not have a tag directory or thematic tags. Her tagging is largely functional and outward facing rather than discursive or personal; she uses authors' names, general search terms such as Dark Academia, books, and poetry, and occasional broad thematic tags, such as "love" or "sorrow." Marlowe is unusual in that she has commodified her blogging; she takes donations and has a membership system in which people pay a small sum to receive daily recommendations of art, poetry, and historical letters; members also have the right to request parallel posts. Many curators solicit requests for themes around which to make parallel posts, as both creative prompt and method to build an audience; Marlowe accepted requests well before her membership system. Her professionalization of parallel posts as a specific product, and nonetheless a product of her own media experience and incorporated into her personal blog, is an inversion of Adair's use of them as progressively more idiosyncratic (note 4).

[4.13] Marlowe shared Siken's work in her first six months as a literary blogger, when she seemed to be quickly reading and watching the media canon of Dark Academia. One of her early When/And posts reads "When Richard Siken wrote 'Everyone needs a place. It shouldn't be inside of someone else' and Jorge Luis Borges said 'So plant your own gardens and decorate your own soul, instead of waiting for someone to bring you flowers'" (note 5).

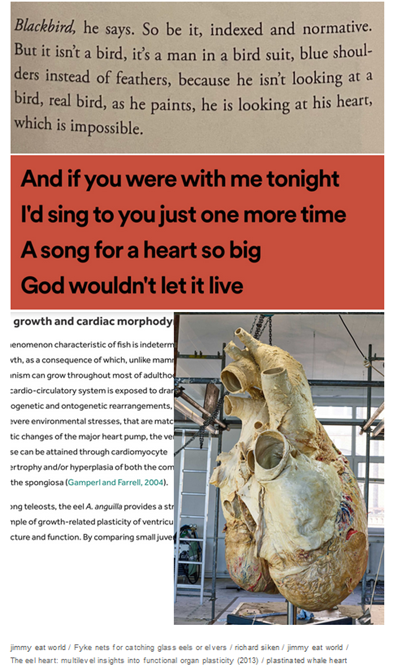

[4.14] Marlowe returned to this theme and this Siken almost two years later in a collaged post themed "musings on making homes out of others" (figure 5). This post features six quotes and three artworks. Marlowe begins with Siken, moves to Norwegian painter Edvard Munch's "Consolation"; a brief line from Hanya Yanagihara's New Adult novel A Little Life; contemporary American painter Alex Venezia's "Returning Home"; a line from John Keats's "To Fanny"; dialogue from the musical Hadestown; a snippet of Amy Lowell's "The Fruit Garden Path"; a painting by American illustrator Mark English; to a quote from British author Warsan Shire's poem "For women who are 'difficult' to love." The three paintings all show pairs of people, one holding the other, and are in similar color schemes of desaturated beige and gold. The text is black on white, all in the same font but for the Hadestown quote, which is a screenshot from a lyric website; it contrasts starkly with the other quotes, centred and in a lighter, sans-serif font. Unusually, none of these quotes seem to have been recontextualized; they align closely with the theme of "making homes out of others."

Figure 5. Marlowe's post, "musings on making homes out of others." 2023.

[4.15] Marlowe dominantly makes collaged parallel posts now, having begun—like many—making When/And posts. Her collages are often multimodal, incorporating images and GIFs. While she focuses on literary work, she uses song lyrics and occasional screencaps and scripts. Where Adair uses parallel posts as one form among many in their blogging, Marlowe treats parallel posts as the end in themselves. She has built up parallel posts as a specific art form and is unusually attentive to aesthetic cohesion. Where collaged posts most often present quotes with their original formatting, enjambment, and punctuation, with contrasting fonts and coloring, Marlowe rewrites content in specific fonts, uses artworks with similar color schemes, and uses snippets of color or visual art between written fragments to enhance unity rather than maintaining their raw aesthetic features (figure 6). When anonymously asked about her creation process, she said the quotes and images she uses are for the most part from texts she has engaged with personally and in full. She stays up to date with Tumblr's favorite texts for quotation over time, while interspersing them with her own preferences. Web weaving has become not just a part of her reading process and social connection but a way of making a living (note 6).

Figure 6. Part of one of Marlowe's parallel posts, showing her use of colored bars. 2022.

[4.16] Adair and Marlowe have experimented with the formal possibilities of what a parallel post can do over time, implying an active and dynamic mode of engagement with texts, their communities, and the creative process of making parallel posts. Where Adair has transitioned from orienting their parallel posts toward others to using parallel posts as a personal creative process, Marlowe has continued making parallel posts as a distinct genre in themselves, meeting the demand of a specific audience. They are united in that their parallel posts crystallize their remembrance, rumination, and return to texts.

5. Bookishness in counterpoint

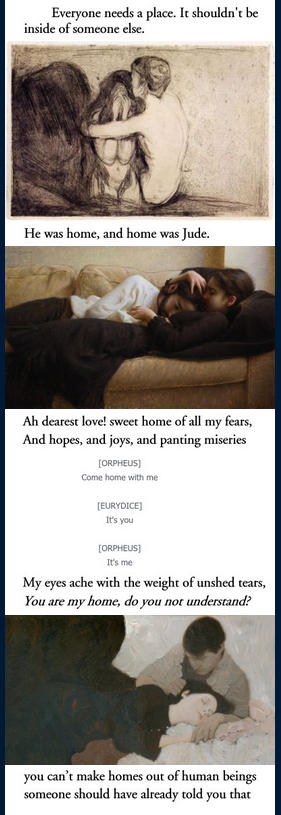

[5.1] As Rogers Brubaker (2020) argues, the defining state of digital life is hyperconnectivity—the constant potential connection to near-infinite content and others. The dominant neoliberal ideology of the need to cultivate the self as a cultural object has been exacerbated by this hyperconnectivity; there have never been more resources from which to self-create—or more, self-curate. Brubaker emphasizes that the digital self is constantly being quantified, whether through active choice such as in the self-quantification movement or by passively experiencing being datafied on social media. Combined with the neoliberal force of self-objectification, the self can always be improved upon in numbers; "the quantified self is therefore a restless and insatiable self" (784). Adair has been reflecting on the restless, insatiable nature of selfhood for years, framing digital abundance as a burden; they discuss "the tragedy of infinity," the fact that "there will always be more books unread than read, more music unheard than heard, more paintings unseen than seen," mourning that "when [they] die, there will be countless more that [they] will never even have the opportunity to love and cry over and feel." Their initial post on the tragedy of infinity has over 19,000 notes; it is a resonant concept for other users. Marlowe discusses her overwhelm at the need to make choices in how her life will play out, saying her "freedom" to make choices and act makes her "miserable." Adair mirrors her in this, asking, "how can i bear to exist when im constantly losing everything to time[?]" Both present autonomy, time, and media consumption as terrifying, even as they pass.

[5.2] Nonetheless, blogging has been a vital part of Adair and Marlowe's lives. Adair has called their blog a "house that i live in," "a place for things i treasure," and "a home for my nostalgia," and credit the blog as "phenomenal" for their "self development and confidence." Marlowe has called her blog "the only place where [she] can openly talk about what moves [her]," "the best thing that's ever happened to [her]," and "one of the very few things that keeps [her] going." Adair has spoken about Tumblr's appeal as being that "there's no sponsorship so there's no person or product there […] it's Just content." This reflects Tiidenberg, Hendry, and Abidin's (2021) argument that some of Tumblr's most significant affordances are high pseudonymity, low searchability, high multimediality, and high nonlinear temporality; these traits demonstrate the balance Tumblr strikes in granting privacy while simultaneously allowing many modes of self-expression, unbound to linear time or the demand for a unified self. The neoliberal demand for self-objectification is obfuscated by Tumblr's emphasis on content rather than individuals, providing a space to archive that which is loved, cried over, and felt in a socially connected but largely self-controlled space. This parallels how commonplacing was understood in the age of enlightenment—it was a way of taking control of unscalable knowledge (e.g., Eichhorn 2008; Jenkins 2015; Lynch 2018). Both Adair and Marlowe's blogs have been driven by a desire to connect with literature on their own terms, both having been detached from reading through high school. This reflects a common trend in bookish communities; as Birke and Fehrle (2018) observe, digital bookishness substitutes schools in sparking passion for literature, and bookish people online reclaim the "central role of reading for self-cultivation" (76–77); across platforms, bookish users emphasize the felt, affective aspect of reading above all else. Literature is claimed as personally, not institutionally, significant.

[5.3] Bookishness, like fandom, is a way of aligning identity with media but not with a specific media property; instead, books come to represent shared ideological, cultural, and aesthetic norms. Pressman (2020) argues that bookishness frames books as a total category, "as outposts from the always-on, constant crisis of information overload […] bulwarks against surveillance culture, global capitalism, and terrorism" (42); this is not unique to the digital age but an extension of what Striphas (2009) identifies as the decades-old treatment of books as privileged consumer products due to their perceived role in "moral, aesthetic, and intellectual development" (6). Performative engagement with books is framed as the essential technology of the self. Despite this ideology, the book industry is embedded in modern capitalism, trade, and inequality (Striphas 2009; McGurl 2021), and bookishness is just as interwoven with surveillance, capitalism, and hyperconnectivity as any other online phenomenon. Birke (2021) argues that mainstream bookishness frames reading more as the bookish goal, regardless of content, comprehension, or personal value; optimizing one's quantified self becomes optimizing one's quantified self as reader. Books are not "outposts from the always-on, constant crisis of information overload" but part of the crisis; there is a crisis of too much to read just as much as too much to be. McGurl (2021) concurs, framing the bookish life as an unsatisfied one—before a book is finished, "already hunger has begun for the next" (7); the restless, insatiable self is a restless, insatiable reader.

[5.4] Adair has poignantly reflected on quantified reading culture, saying,

[5.5] not a fan of the YouTube Book Culture of like. learning speed reading techniques and How I Read 100 Books In A Month and blah blah blah like it is sooooo not about numbers. like what happened to treasuring each book!! […] anyway lately i've been reading slower on purpose and i read multiple books at once, slowly. […] im soaking up each one as i read the others. growing a little fungi garden in my brain. […]

[5.6] Adair's desire to consume all art and knowledge available to them conflicts with their knowledge that it is both unattainable and not necessarily the most productive or enjoyable mode of reading. Adair posits intratextuality as something essential to the reading process by highlighting that media engagement is enriched by other texts; the "little fungi garden in [their] brain" is something to be nurtured and fed as a whole. While there is abundance in Adair and Marlowe's blogging, there is also rumination, recursion, and growth; no parallel post could be made without dwelling within and between texts.

[5.7] Bookishness is amid a fragmentary moment—from decontextualized quotes as markers of bookishness, Instapoetry, Amazon Books's highlight feature (Rowberry 2016) to the rapid reviews of Goodreads and BookTok, TikTok's bookish culture. Parallel posts are of this fragmentary moment—they are made of fragments—but they subvert it by demanding that the curator dwell, connect, and extend sentiment. Users create broad webs of understanding and affiliation through parallel posts, entailing both individual reflection and community engagement; rather than performing the self as a coherent whole, parallel posts present the self as a transtextual assemblage. Personal voice, authenticity, and individuality are the defining terms of bookishness (Pressman 2020)—and indeed, digital media overall (Brubaker 2020)—and parallel posts most often lack personal voice entirely; if a curator uses their own words, it will likely only be in a post's title or the tags. In parallel posts, like in Foucault's (1983) hupomnemata, a curator needn't understand the whole of a text to take personal value from it; they process and link information in fragments, thereby mingling text, tissue, and blood. Parallel posts demonstrate the intimacy of curation—the user archives not their own words but their own textual experience; texts are filtered and transformed through the self, even as the curator withholds their voice. Similarly, where materiality defines much of digital bookishness (Pressman 2020; Thomas 2021; Birke and Fehrle 2018), there are few visuals of books in parallel posts; they evoke the physical act of collage, but they simultaneously disembody quotes because of how small they have been cut. In an intensified version of Tumblr's focus on content rather than individuals, bookishness in parallel posts avoids both the material form of books and the curator's bodily relationship with the world. On a broader scale, the fragmentary nature of parallel posts obfuscates much to do with cultural capital; parallel posts blur cultural lines as semantic proximity, and acuity of phrasing take precedence over equivalence of cultural standing—the differences between texts are stripped when they are transformed into equivalent snippets.

[5.8] Parallel posts are bound to transformation. They are transformations of self; transformative artifacts, created through the cutting, recontextualization, and reformation of texts; and emerged from a transformative culture rooted in fandom's overlap with queer, bookish communities on Tumblr. As parallel posts branch out into different uses and independent prevalence, Dark Academia remains their origin, and a study of parallel posts would be incomplete without considering its impact. Dark Academia reflects the status of books and education in the modern age, as a subculture/subgenre/aesthetic/publishing category that has at its heart the desperate desire to grasp knowledge; it is an aestheticized anxiety of abundance. As Fathallah (2020) argues that the subculture and genre of emo was a self-created force born of fandom, so too is Dark Academia. In both cases, the driving force is intratextuality; elements from different media are connected through application of cultural meaning with a unified name, and in so doing, a referent is created—the thing itself, consisting of nothing inherently but the intersections from which it has been named. Dark Academia is not fandom for Richard Siken, Hozier, or The Secret History; Dark Academia is the text of their intersections and simultaneous use. This complexity is inextricable from the transformative culture it emerged from—and indeed, from those who use the name. Marlowe, like many, often tags personal posts with "Dark Academia"; her personal stories are as much a part of the phenomenon as her parallel posts, quotes, and reflections on reading. Dark Academia's flesh is inseparable from the lives of its proponents—quotes, images, music, and much else come together as one networked technology of the self; parallel posts crystallize them.

[5.9] Parallel posts are a transformative, contrapuntal expression of digital bookishness—of the same substance, filtered through Tumblr's queer and fandom cultures. In parallel posts, the raw material of digital hyperconnectivity—abundance, fragmentation, and speed—is unveiled as it coexists with the powerful drive to linger, to repeat, and to archive.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] As parallel posts cast light on Tumblr's norms and aesthetics, they unveil the persevering impulse that defines commonplace books as much as fandom: to dwell within and to internalize media. De Kosnik (2016) argues that creating and consuming fan works are "acts of remembrance," mementos of both the text and the audience's affective experience of it, and when fan works are archived, acts of remembrance are aggregated (29). Each user incorporates their own memory, and then it is shared, and then it is remembered, and then it is shared—and so it continues, networked memory between networked selves. Each parallel post is a snapshot of personal media reception, brought into negotiation with thousands of others by the connective tissue of hashtags. They are both symptom and salve of a boundless reading culture.

[6.2] I posit that a question that lurks beneath the surface of much scholarship on bookishness is "what does it mean to be a 'reader' in an age of digital hyperconnectivity?" While parallel posts cannot answer this question in full, they highlight many avenues of exploration. To be a reader is to take from different sources voraciously; to experience ceaseless multimedia; to drift in and between fandoms; to blur lines of cultural capital; to battle impulses of consumption and rumination; and to lurk in ambiguity and overwhelm, forging one's own voice through a chorus of others'. Tumblr has been defined by polyphony since its inception; it is only appropriate that it be studied as exemplar of what it means to experience media in a polyphonous, hyperconnected world.

7. Acknowledgements

[7.1] This research is funded by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. I thank my supervisors and advisors, Paul Dawson, Craig Billingham, Stephanie Bishop, Sean Pryor, and Michael Richardson; my workshop group; TWC's reviewers; and the Renegade Bindery, for their invaluable time and support.