1. Introduction

[1.1] BobaBoard is an in-development fandom-centric social media platform that strives to create a space of belonging and acceptance for what the founder described to me as a "niche group of weirdos." Two ways this emerging community is creating a protected space where media fans can explore and share their sexualities are through an anonymity-first design and a core ethos of anti-censorship (Notion n.d.). However, these goals are neither simple nor easy to implement, and there are both affordances and limitations to BobaBoard's anonymity-first and anti-censorship approach. Through digital ethnographic fieldwork undertaken in the spring of 2022, I found that the strategies and innovations through which these tensions are negotiated illustrate emerging community ethics around the cocreation of fan spaces and the exploration of sexual fantasy in these spaces. These community ethics demonstrate the possibilities of collaboratively creating protected spaces for sharing desire and sexuality.

[1.2] BobaBoard's collective ethical practice, or what was described to me as a sense of "social responsibility" shared by members of the community, is a key way that the platform's users navigate the uncertainties and challenges of creating BobaBoard, both as a social media platform and as a community. This social responsibility, a sense that every user is responsible for cocreating BobaBoard's nascent culture, speaks to broader scholarly conversations about ethics, values, and how people collectively understand what is good (Robbins 2013). Previous work on the ethics of sexual fantasy in Japanese fandoms (Galbraith 2021) is resonant to issues central to BobaBoard, and similar to that work, I found that the BobaBoard community is preoccupied with other kinds of ethics, including an "ethics of care" (Busse 2018, 5) for other users. BobaBoard's ethics are also an ethics of community-building or "world-making" (Lothian 2016, 744), which is embedded within but ultimately goes beyond an ethics of care. Through these ethics, the community of BobaBoard is working toward a better platform and a better fandom.

2. Background

[2.1] BobaBoard lies at the intersection of several contexts: media fan cultures, debates within these fan cultures about sexual expression, and the ongoing censorship of pornography and sexuality by large social media platforms. As fan studies scholars have noted, fan cultures have often been a place for the exploration and expression of sexuality and sexual fantasies (Busse and Lothian 2018), with fans creating "secret worlds of erotic kinship" (Lothian 2016, 746). Sexuality thus has an important place in fandom, and BobaBoard often revolves around fan cultural productions, especially those that are pornographic or sexual in nature. Even as sexuality is central to cultural practice for many fans, there are challenges on multiple fronts to the ability of fans to freely express sexual fantasy.

[2.2] One challenge is continuing corporate censorship of sexuality by media platforms. A major corporate challenge to erotic fan media, and one of the main factors behind BobaBoard's creation, was Tumblr's move in 2018 to ban sexually explicit content, which resulted in many users leaving the platform (Edwards and Boellstorff 2021). Before the ban, Tumblr was a "key hub of multimedia online fandom activity" (Morimoto and Stein 2018), and the creator of BobaBoard told me that the ban was the main impetus for the creation of the platform, explaining that "no [venture capital]-backed company is going to be a haven for us." Effectively, she was telling me that any corporate platform is bound to be a precarious place for fandom. BobaBoard is thus responding to a need to have a platform independent of corporate control where fans can be free from worry of censorship.

[2.3] In these goals, Bobaboard can be compared to other platforms built by and for fans, such as the fan fiction repository Archive of Our Own (AO3), which was founded with similar goals and values of combatting censorship and creating a platform under fan, and not corporate, control (Lothian 2013). It is significant that both platforms share the ideal of fans owning the servers themselves, thus having more control over the platforms—AO3 was in part a response to censorship by platforms like LiveJournal and Fanfiction.net (Fiesler, Morrison, and Bruckman 2016), the same trends of corporate commodification and censorship of fandom that BobaBoard is responding to. Like AO3, BobaBoard's development is driven by the community and its values. This development is open source, and BobaBoard actively facilitates members of the community in learning how to code and joining the platform's development, much like AO3 does (Fiesler, Morrison, and Bruckman 2016). There are also differences between BobaBoard and AO3: for example, BobaBoard is planning slower growth and an eventual decentralized model compared to the large and centralized AO3. While AO3 is built with the aim of archiving fan texts, BobaBoard is closer to other platforms on which "fan culture's online practices exceed the…archival model" (Lothian 2013, 550). Additionally, unlike AO3's idealistic goal of making all fans welcome, which is difficult to implement in practice (Fiesler, Morrison, and Bruckman 2016), BobaBoard is realistic in its targeting: while it is pluralistic and welcomes people who share the community's broader values, it is not being created for all fans. Fans who do not share its fundamental values are not necessarily welcome.

[2.4] BobaBoard's realistic outlook about its targeting is related to another challenge to sexuality in fandom: recent controversies in fan cultures about representation of certain sexual fantasies in media. Although they are known by a few different names in fandom, I call these controversies the "fandom sex wars," since as Kristina Busse argues, the debates occurring in contemporary fandom bear much resemblance to the feminist sex wars of the 1980s, in which feminists divided over the issue of pornography into antipornography and sex-positive camps (2018; see also Derecho 2008) (note 1). Much like the 1980s feminist sex wars, the fandom sex wars are heated and hostile: fan activist and scholar Samantha Aburime (2022) writes of the extensive harassment and death threats that can be perpetuated by "antis." Although the term "anti" is imperfect—contested, mutable, and polyvalent—and the discourses around antis are deserving of more nuance (TWC Editor 2022), this term is nevertheless central to the context of the fandom sex wars. In this context, antis, the fandom equivalent to the 1980s antipornography feminists, campaign against what they see as dangerous and immoral media. At issue in these debates is the representation of stigmatized sexual fantasies—for example, rape or incest fantasies—in fan media. Antis largely believe that one's sexual fantasies are equivalent to real-world desires and thus argue that the presence of extreme fantasies in media will lead to real-world harm, while the fans opposed to antis maintain that there is a separation between desires in fantasy and reality (Busse 2018; Aburime 2022) (note 2). As I gleaned from participant observation and interviews, these debates are another major factor behind the creation of BobaBoard, which is a space for fans to share their fantasies without judgment or harassment. Coming out of the 1980s sex wars, the anthropologist Gayle Rubin wrote in her foundational work "Thinking Sex" that "it is up to all of us to try to prevent more barbarism [i.e., sex negativity, the legal/social persecution of sex] and to encourage erotic creativity" (2007, 171). I see BobaBoard as one community's effort to carry out this mission in the context of fandom.

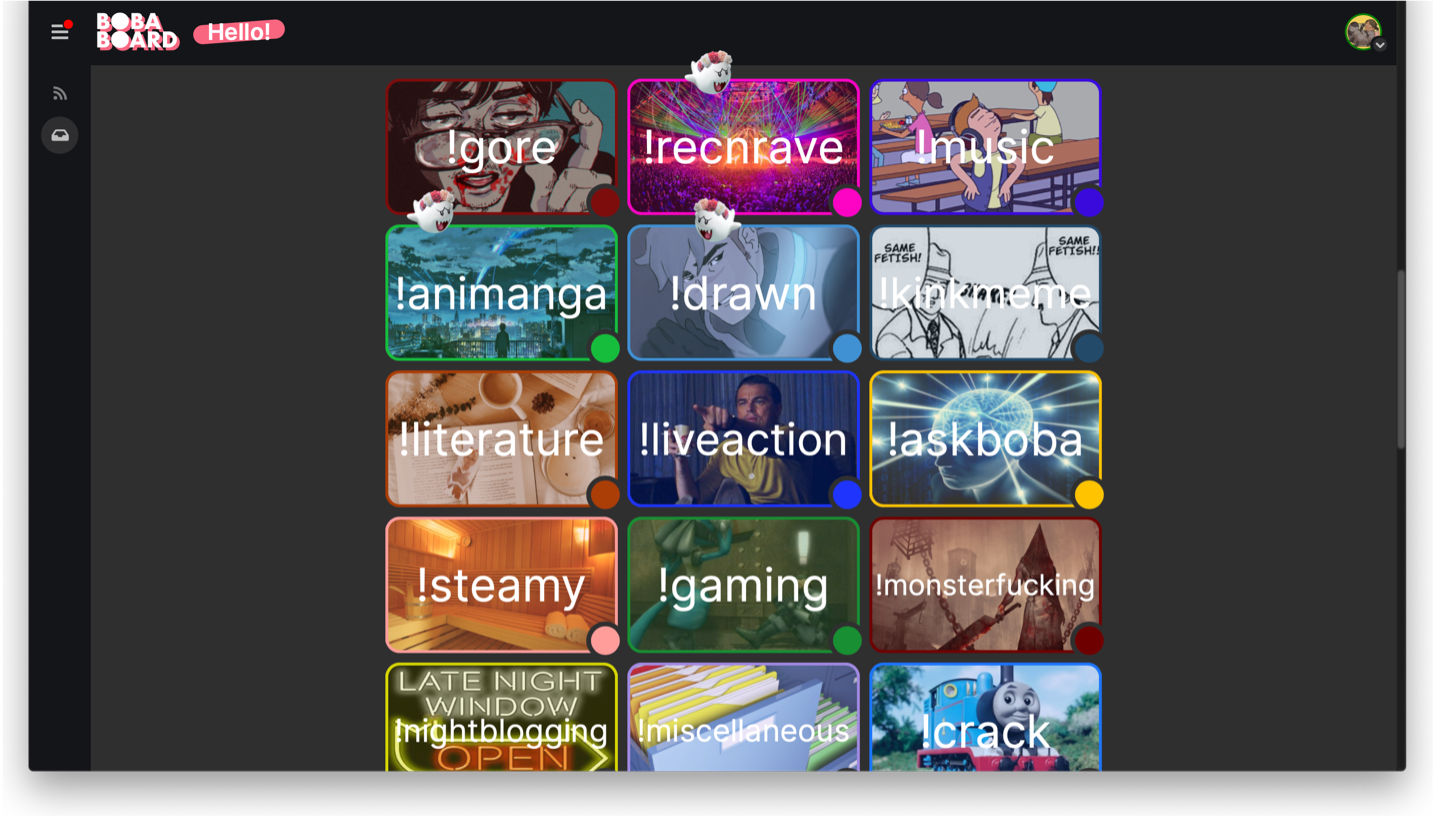

[2.5] Responding to these contexts, BobaBoard's goals are to create a space where fans can freely express and share sexual fantasies without judgment from other fans. The design and operation of the platform are central to this mission. BobaBoard is divided into different boards (themed collections of threads), for example !music or !steamy (figure 1). Users can add different kinds of tags to their posts, including content notices. Perhaps the most important aspect of BobaBoard's design is its implementation of "per-session anonymity" (Auerbach 2012): BobaBoard is built around the precedence of anonymity (note 3). On BobaBoard, you do not have a consistent identity to use throughout the site or a user profile that other users can click on (note 4). Instead, you are randomly assigned one of a plurality of preexisting "identities" on each thread you interact on (figure 2). This randomly assigned identity remains consistent in that thread, which enables in-depth conversations, but when commenting on a new thread, you are assigned a new identity. As I learned in my research, this anonymity system is a central means by which the community of BobaBoard hopes to fulfill its mission.

Figure 1. BobaBoard's front page. Screenshot by the author.

Figure 2. An identity on Bobaboard. Screenshot by the author.

[2.6] There is much scholarship on anonymous online platforms, which considers both positive and negative aspects of anonymity. Literature often focuses on platforms that, in addition to being anonymous, are also ephemeral (posts quickly disappear) and analyzes how the combinations of these and other affordances affect how people interact on these platforms. For example, some scholars argue that the design of Yik Yak, which includes anonymity, ephemerality, and hyperlocality, enables bullying and harassment on the platform (Li and Literat 2017), though other scholars contest this framing and emphasize the positive effects of anonymity that Yik Yak can provide (Bayne et al. 2019). Early studies of the infamous imageboard 4chan, which is anonymous and ephemeral, often write of the generative possibilities of the site but also note its culture of offensiveness and trolling, including racist and misogynistic content (Knuttila 2011; Auerbach 2012). At least in 4chan's early days, this offensiveness may have been largely ironic—a kind of repellant to outsiders that functioned as cultural capital (Manivannan 2013), though no less exclusionary to minorities—but the trend in recent years, especially on 4chan's board /pol/, is toward a more virulent bigotry that has bolstered real-life extremism (Tuters and Hagen 2020) (note 5). BobaBoard is a platform that was created to provide the benefits of anonymity without the drawbacks. What I found is that along with design and affordances (including anonymity but not ephemerality), BobaBoard's users collectively shape the culture of the platform to achieve this goal.

3. Methods

[3.1] This article is based on about two months of digital ethnographic fieldwork in the spring of 2022, including participant observation on BobaBoard and two semistructured interviews with community members. In addition to gaining approval from my university's institutional review board, I also sought out permission from the BobaBoard community itself about conducting research and worked with them to define limits and ethical principles to my research (note 6). My analysis is refined from major themes identified through manual coding of my field journal and interview transcripts. For considerations of space, my methods and ethics are explored in more detail in an appendix.

4. Is anonymity truly anonymous?

[4.1] Anonymity is a central feature of BobaBoard, but to my surprise, I found several different positions on anonymity from the BobaBoard community, not all unambiguously positive. This came to light in my interview with a user who (for the purposes of this ethnography) I have called Damian, a gay trans man who has often faced bullying and harassment in fandom, which contributes to his ambivalent position on anonymity. As Damian explains, while he has currently not had poor experiences with anonymity on BobaBoard, he is worried about the possibility of previous abusers joining the platform in the future and discovering his identity through writing style, despite the anonymity features of BobaBoard:

[4.2] I'm getting along with [anonymity] better than I initially expected. But I think a lot of that has to do with how small the community is […] Part of me is worried that […] at some point […] I will end up […] with either my primary abuser or someone else who reacted violently to discovering that they were interacting with me […] The biggest risk at this point—is…how the anonymity factor interacts with…what it means to have to presume slash trust in…good faith on everyone's part.

[4.3] At this point, I asked Damian why he thought anonymity is the risk factor here: would not anonymous interactions be safer precisely because they're anonymous? But he told me that past experiences with "anonymous" interactions led to people identifying him and "reacting violently to doing so." He explained, "It's easy to do limited cross-referencing between…posts to identify me…And, you know about the having to trust that anyone invested enough to do that is doing it…because they want to be friends." What Damian gets at here is something that I have seen myself and that has been echoed by a few other users: the ways in which, despite the technological design of anonymity, identity still creeps into the system. This is due to the nature of social interactions: individual personality, interests, and writing style all serve to mitigate the designed anonymity to some degree. The size of the current BobaBoard community is likely another factor: the current userbase of BobaBoard is small, so it becomes easier to identify people based on interests or other individual factors. If the community were larger, then one might be more anonymous, but a larger community might present its own set of challenges.

[4.4] Damian's ambivalence about anonymity struck me as a stark contrast to the perspective of the founder of the site, who goes by Ms. Boba among other pseudonyms, who emphasized the positive effects of anonymity and framed it as perhaps the central defining feature of BobaBoard. When I asked her why anonymity was so important, Ms. Boba answered with a personal story:

[4.5] My best friend and I—we met 'cause they used to send me anon asks on Tumblr. […] So they are very, very private as a person […] And I think the other bit of that was that, you know like the fandom climate is these days […] I basically got […] a lot of shit for […] the problematic stuff, […] but she stayed unscathed, protected by anonymity. […] Everyone is worried about, "oh, I cannot say this, I cannot say that, like, if I ship this ship, I'm just going to get all that harassment towards me," and […] let's just avoid that. […] And then I actually talked with more fans, and […] I was like, "Where do you find good content?," and they were like, "You know, I hate the environment there, but if you go on 4chan these days, that's where you find the really juicy stuff."

[4.6] There are several things about this origin story worth noting. One is the place of the fandom sex wars in the founding of BobaBoard: fans get harassed for what others believe to be immorality, but those who remain anonymous manage to avoid this backlash. And then, truly anonymous platforms allow people to share content expressing sexual fantasies without fear of personal attacks—the "juicy" content can be found on 4chan because people can freely share sexual fantasies there under the cover of anonymity, although this is accompanied by the major problem of the bigotry also found on the platform. For Ms. Boba, then, anonymity is key to making BobaBoard a space where fans—especially those with niche or stigmatized interests—can feel belonging and share their fantasies. However, there is another aspect to her story that surprisingly echoes what Damian says. Ms. Boba met her best friend through anonymous interactions online—but even before they revealed themselves to her, they got to know each other through those anonymous interactions. This once again points at the ways that some form of identifiability or identity can reemerge even when a platform is designed to facilitate anonymous interactions.

[4.7] Struck by the contrasts and resonances between these two interviews, I asked the BobaBoard community at large what they thought about anonymity on social media platforms, including BobaBoard. I received a diverse range of perspectives, carefully thinking through the benefits, drawbacks, and limitations of anonymity, such as the ability of anonymous spaces to avoid a culture of personal branding but the potential of anonymity to change the way you perceive others. For considerations of space, I will focus on one response that pointed at the benefits of anonymity in fandom in light of the fandom sex wars. This respondent usually lurks in online fandom spaces and sees no benefit to using an identity, writing that with "how the current digital climate is"—accusatory, regressive, exclusionary—"not being anonymous is almost all cons for me at this point." This user points to the fandom sex wars as a reason that posting under a known identity has become potentially dangerous in online fan spaces. Because of the possibility of a stranger passing judgment on them because of the art they consume or post (which may not reflect their real-life beliefs) or their identity, the cover of anonymity is safer for them.

[4.8] This user also identified a "certain sense that it's on us to make this a place we want to hang out in" or a "sense of social responsibility" that helps shape the burgeoning culture of the site. This is contrasted, in their account, to users on anonymous platforms like 4chan, who use "anonymity like a cloak and a weapon"—in other words, who have a culture of using anonymity as a cover to spread toxicity. In contrast, this user believes that on BobaBoard, anonymity helps shape a culture of tolerance and not toxicity: even heavy disagreements are "still framed in my mind as a disagreement with a person I don't mind sharing a space with," which is different from the cultures of most other online platforms.

[4.9] There are several conclusions that can be drawn from considering these perspectives together. Some users see anonymity as a way to protect themselves from toxic internet culture and a way to facilitate self-expression, but others see risks to anonymity, including providing cover for abusers. The ways that identity reemerges on BobaBoard demonstrates how the personal, cultural, and social mediates the technological (Alberto 2021). Thus, because of sociocultural factors, interacting with others involves trust that others are good-faith actors, as Damian put it, and the design and social interactions of BobaBoard involve a certain level of managing risks both of nonanonymity and of anonymity. One way these risks are mediated is through developing a culture of "social responsibility," which suggests emergent forms of community ethics.

5. Sexual fantasies, anti-censorship, and protecting others

[5.1] Another core aspect of BobaBoard is its anti-censorship ethos: being able to freely express sexual fantasies and share media about those fantasies without fear of censorship from the platform or ostracization from other fans. This anti-censorship position does not mean, however, that anyone can say whatever they want. As I discuss below, BobaBoard does not allow speech that would harm others ("BobaBoard's Welcome Packet" n.d.)—what this means in practice and how it gets negotiated is where one can again see the "social responsibility" or ethics of the userbase. In particular, what I learned from the BobaBoard community is the importance of tagging contentious material and respecting other people's personal boundaries when expressing sexual fantasy. These practices emerge from both the design of the platform and the social norms that have built up around it.

[5.2] BobaBoard's version of freedom of expression is the right to express oneself as long as it does not harm others—which requires a shared understanding of "harm" among the members of the BobaBoard community. When I first registered to join BobaBoard, I was sent to a welcome page that expressed this ethos explicitly: "Be as nasty as your heart desires towards fictional characters, but excellent to other [users]" (BobaBoard, account creation screen upon the author's registration, March 3, 2022). The division of fiction and real life speaks to a collective ethics of sexual fantasy, similar to ethical positions that have emerged in fan cultures in other places, such as Japan (Galbraith 2021). It also stands in contrast to the position of antis in the fandom sex wars, who see harm as coming from the expression of sexual fantasies in fiction, which they believe have the power to lead to real-life harm (Aburime 2022). BobaBoard promotes a different understanding of harm among its userbase: one can harm other people through how one interacts with them, but real-life harm does not necessarily come from sexual fantasies. Hence the reminder I got when I joined the site: feel free to harm characters in fiction or express taboo fantasies involving them, but strive not to harm real people in doing so.

[5.3] Although sexual fantasies are not considered innately harmful by the BobaBoard community, the question of what is harmful and thus forbidden remains. As I learned, the limits of free expression and the definition of harm on BobaBoard are sometimes ambiguous, but purposefully so. There is a recognition that defining the limits of expression is difficult and that these limits will have to be collectively worked out by the community. When I asked her, Ms. Boba gave a very nuanced answer about the ambiguity of defining limits to expression:

[5.4] I think there's various ways of doing it, so there is, "anything that's legal [is allowed]"—and I think that's a very simplistic answer. […] You know, there is harassment; there are things that can border on legality that eventually you have to, at some point, do some judgment call on where the line falls. And I think I do not have a straight answer because part of the journey is figuring that out […] I really see myself and everyone in the community as allies in trying to figure out what our limits are and what the culture of the overall place should be like. […] I don't really think that it's a matter of content as much as it's a matter of […] the community that results from that content and what the community wants to accept. […] I think people say a lot of platitudes here…that then in practice, at some point, they're gonna have to walk back on.

[5.5] Ms. Boba resisted giving a "simplistic answer" because she knew that the practicalities of defining what is allowed and not allowed on the platform are anything but simplistic. She pointed toward the community collectively deciding where to draw the line and gestured toward this practice of drawing lines as part of collectively negotiating what the "culture of the overall place should be like" (note 7).

[5.6] These sentiments are clear from the platform's messaging. The landing page for new users reads, "you have real power to influence the developing culture on this platform" (BobaBoard, account creation screen upon the author's registration, March 3, 2022). From the minute users first join the site, communication underscores the importance of collectively guiding the community's culture and norms: the social responsibility that is cultivated includes negotiating where to draw the line on behaviors and expressions that are or are not allowed. BobaBoard's public-facing website also makes the existence of limits clear: "Be mindful: BobaBoard is a moderated community with strong anti-harassment and anti-bigotry policies" ("BobaBoard" n.d.). What is clear is that although BobaBoard is anti-censorship when it comes to sexual fantasies and their expression, there are still limits to expression and speech that are negotiated by the community, and these limits go beyond the distinction between legality and illegality. There will have to be lines drawn by the community based on the culture that emerges on the site.

[5.7] The everyday negotiations around speech/expression that happen on BobaBoard are centered around respecting others' fantasies (not shaming people for their fantasies) and respecting the boundaries of others, values which can sometimes be in tension with each other. What if you encounter material that you personally do not want to see, perhaps material that brings up trauma in your past? What if someone brings up or posts material that is anathema to you on a thread that you have started? This is a very real thing that happens, and the ways situations like this are negotiated speak to BobaBoard's emergent community ethics.

[5.8] After registering for BobaBoard, I was led to an external site containing a "Welcome Packet" for new BobaBoard users. Among other things, it details the guidelines and policies that currently exist on BobaBoard. This is an important document for understanding the community norms currently in place and where lines might be drawn in terms of policies and moderation. Along with several "dos"—"Be Kind," "Be Weird," "Be Supportive," "Deescalate Conflict"—there are three "don'ts." The first is "Don't be an asshole" ("BobaBoard's Welcome Packet" n.d.), a catch-all for antagonistic and bad-faith behavior, but the other two require elaboration, as these are key to how conflicts around sexual fantasy are handled on BobaBoard.

[5.9] The final two "don'ts" together outline the ways in which conflicts around sexual fantasies can be avoided or managed. The first is "Don't yuck someone else's yum" ("BobaBoard's Welcome Packet" n.d.)—in other words, do not make fun of, attack, or shame people for their fantasies, preferences, or tastes. This community standard gets at the core values of BobaBoard and one of its central goals: to create a space where fans can express their sexual fantasies freely, without fear of judgment from others. If anybody did not get the message from the process of gaining access to the invite-only community, the welcome packet makes it clear: shaming others for their fantasies—yucking their yums—is verboten.

[5.10] How, then, to deal with content on the site that you do not want to see? One answer is through the norm of tagging contentious material, which I address below. Tagging does not, however, solve the issue of others' posting content a user is averse to in a thread they have started. This is where the final community guideline listed on the welcome packet becomes relevant: do not "continue pressing an issue after someone has asked you to stop. In threads, OP [i.e., the original poster] has final saying on what is allowed on their thread. Making a different thread to discuss something OP would rather not touch upon is allowed, but try to avoid 'subtle' jabs at the previous OP (trust us, they're never subtle)" ("BobaBoard's Welcome Packet" n.d.). This is the second important community norm for handling conflict: in addition to respecting the fantasies of others, users are entreated to also respect the boundaries of others. This includes stopping when the creator of a thread asks you to stop and respecting that decision by not bad-mouthing them in other threads. (One could say that in addition to not "yucking other people's yums," BobaBoard's guidelines also ask you to not "yuck [complain about/attack] other people's yucks.") The ways that these two policies work together in practice demonstrates how the BobaBoard community strives to create collective ethics.

[5.11] In my interview with him, Damian told a story from early in his use of BobaBoard that I later learned was the origin story of this last policy. From his account and those of others, I have reconstructed what happened: one user made a joke involving vorarephilia (or "vore," the sexual fantasy of being swallowed or eaten) on an unrelated thread. This joke ended up making another person uncomfortable and caused some conflict, with the original poster of the thread supporting the negatively affected user. This caused its own problems, according to Damian: "[It] triggered a rejection-sensitive dysphoria spiral in the person who made the vore joke…and also made, I want to say like four people, jump on them going, 'Obviously what we need is a feature allowing you to add a flair saying that you are the person who does not want people to make vore jokes in their threads. '" But Damian disagreed with that sentiment: "What had happened…was not…a failure; that was a perfectly reasonable conversational success. Someone hits a boundary they're not aware of; someone else goes, 'Oo, oo, not that actually.' The conversation stops there and otherwise moves on."

[5.12] At this point, I was dubious regarding Damian's characterization of this as a success: what about the rejection-sensitive dysphoria, or distress from the perception of social rejection (Bedrossian 2021)? Would it not be better for them to hide the vore content so they did not see it rather than asking the vore poster to stop? However, as Damian explained the practical implications of my idea (vore content could spill over onto the rest of the thread) or the other suggestion put forward by users (a flair about not wanting vore would effectively kill anonymity), I was persuaded to see this as a successful example of the BobaBoard system in practice. The rejection-sensitive dysphoria was unfortunate, but this was the best way the conflict could have been resolved.

[5.13] As Damian sees it, BobaBoard's community standards provide a way to effectively resolve conflict in a way that minimizes harm and toxicity. Rather than pretending that the conflict does not exist, which can exacerbate it—Damian believes that toxicity in fandom spaces often "comes from people […] minimizing conflict and the appearance of conflict"—these community norms of respecting both others' fantasies and others' boundaries provide tools to address conflicts head-on and resolve them. There is a distinction to be made between "I personally dislike this" and "you are bad for liking this," and in this distinction, in the dual respect for fantasies and personal boundaries, lies BobaBoard's emergent community ethics.

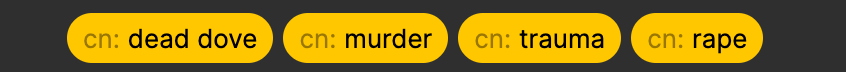

[5.14] A second way that the ethics or social responsibility of the BobaBoard community comes to light with regards to freedom of expression is with community norms of tagging or providing content warnings for contentious material. As part of its technical design, BobaBoard has several kinds of tags for posts. All these types include the possibility for custom tagging, though one type ("category tags" intended for filtering) also has contextual lists of possible options to choose from. Importantly, another of these types is the "content notice" (CN) tag for potentially offensive, contentious, or otherwise off-putting material. These tags are displayed on top of a post in a bright yellow color to make it easy for people to see them and quickly evaluate whether they want to see the contents of the post (figure 3). If a post contains tags that a user does not want to see, they can then hide the post. Tags can be added retroactively after a post has already been published if a user forgets a tag or realizes they should add a content notice. The technical flexibility of the tagging system encourages the social norm of tagging for content notices, creating another means by which the BobaBoard community embodies collective social responsibility.

Figure 3. Content notices found over a post. Screenshot by the author.

[5.15] From what I have witnessed, the BobaBoard community tags content notices even when they do not strictly need to. The welcome packet explains: "There's no particular obligation to add CNs as of now, which might change for specific boards as the community expands. Generally, BobaBoard is a 'choose not to warn' environment, but we try to put an effort to warn for common less-tasteful topics on boards not dedicated to them" ("BobaBoard's Welcome Packet" n.d.). "Choose not to warn" is a phrase that comes from the fan fiction site Archive of Our Own, which indicates that an author has chosen not to apply content warnings to their work—in effect indicating that a reader could encounter contentious material but not warning what that material is (Lothian 2016). Applied to BobaBoard, it means there is a shared understanding that one could encounter contentious material on the site, but even though there is no obligation to tag for content notices, there is a community norm of doing so, and so users apply content notices with great frequency. On BobaBoard, content notices proliferate, warning other users of content that may be distressing.

[5.16] The liberal use of content notices on BobaBoard is a social norm that speaks to the ethics and social responsibility that have developed in the site's community. Content notices are built into the technological design of the platform, which demonstrates that Ms. Boba and the other developers find them important, but the way they are used demonstrates the cultural norms that have developed through the ways people use the platform. In some respects, these norms and affordances are specific to Bobaboard, but they are no doubt also influenced by norms surrounding content warnings on other fannish platforms and in other fannish contexts (Lothian 2016), speaking to a more general subcultural norm of tagging that transcends individual platforms. On BobaBoard, content notices serve as an important way for users to protect each other and promote respect for each other's boundaries, while also allowing for the self-curation of what one personally wants or does not want to see.

[5.17] Alexis Lothian writes of the debates about and norms around content warnings in fan cultures and frames warning for content as a "utopian practice of care" and part of "fannish world-making practices" (Lothian 2016, 751, 755; see also Busse 2018). In tracing the long history of content warnings in fandom, she also makes the important point that content warnings have a function in not only warning away those who might be distressed by the content but also inviting those who might be attracted to the content. Warnings can mark "the entryway to secret worlds of erotic kinship" and "have become part of an infrastructure in which the main goal is to maximize readers' pleasure" (Lothian 2016, 746, 748). To this end, Lothian points to how some fan institutions frame them not as "warnings" but as "notes," to avoid an "overtone of policing" and emphasize pleasure (Lothian 2016, 753–55), a use of language which BobaBoard follows with its "content notices." Thus, tagging on BobaBoard is an important way that users of the platform cultivate collective social responsibility: a responsibility of looking out for each other by warning others of potentially distressing content—but also, as Lothian reminds us, a responsibility that highlights the importance of pleasure and "erotic kinship."

[5.18] In spite of, or because of, the values of freedom of expression at the core of BobaBoard, the community has created shared norms, sometimes edging into site-wide policies, of respect both for fantasies and for personal boundaries. Speech is allowed as long as it does not harm others, and negotiating what that harm is and how to resolve conflicts while minimizing harm is a question of ethics, or the "collective responsibility" for each other and the community at large that the users of BobaBoard have cultivated (note 8).

6. Ethics of care, ethics of world-making

[6.1] Anonymity and freedom of expression are two central tenets of BobaBoard as a platform, but what I have learned from the community is that a collective sense of "social responsibility," or collective ethics, are key to avoiding the potential pitfalls of anonymity and making it possible to freely express one's sexual fantasies. In other words, I have learned that ethics are a central issue in the culture of BobaBoard's community. Issues of ethics speak to broader theoretical questions in anthropology about how people craft their lives and try to live their own best lives. Joel Robbins coins this theoretical current as the "anthropology of the good," which explores the "ways people organize their…lives in order to foster what they think of as good" (2013, 457). What I have learned from the users of BobaBoard are small but important ways that they collectively foster what they think of as good within the BobaBoard community.

[6.2] One recent work falling into this theoretical tradition that finds particular resonances with BobaBoard is Patrick W. Galbraith's (2021) The Ethics of Affect. Galbraith's ethnography focuses on the ways that creators and fans of bishōjo games (part of larger otaku subcultures in Japan) promote and embody an "ethics of affect" and what I would call an "ethics of sexual fantasy." This means that these fans draw a line between fictional characters and real people while orienting sexual desire toward the former; for Galbraith, this demonstrates an ethical position of not harming real people, even as characters are abused in fantasy. Galbraith's work could do much to inform the debates of the fandom sex wars, which are all about whether real harm can arise from sexual fantasy. For the BobaBoard community, the ethics of sexual fantasy seem largely a given (though not without nuances): the BobaBoard ethos is in opposition to that of antis, who believe in harm arising from sexual fantasy. (Recall the encouragement to be "nasty" to fictional characters but "excellent" to other users.) However, what stood out to me were other ethics that are shared among the community as common values: ethics of interacting with others, ethics of sharing sexual fantasy, and ethics of community-making.

[6.3] The BobaBoard community is very concerned with issues of ethics, both the collective "social responsibility" of each user to the broader community and ethics in the outside world. The kinds of social responsibility that I learned from the community are intrinsically tied up with BobaBoard's founding mission and core values: responsibilities that come with an anonymous system and with the possibilities of sharing sexual fantasy without harming others. Anonymity demands trust—this is what I learned from Damian—a trust that the community has cultivated a collective responsibility and shares similar values. Common values are also necessary when sharing sexual fantasy: the members of BobaBoard understand that harm can come from disrespecting others' fantasies and others' boundaries. With the standard of respecting other users of the site, no matter their tastes or preferences, BobaBoard's users are equipped to resolve conflicts head on; they embody an "ethics of care" (Busse 2018, 5) (note 9). The collective "social responsibility" is not only an ethics of care, however; it is also the responsibility of building a space together, which is entangled in the ethics of care but goes beyond it. This is the ethics of "world-making": the responsibility and ethics of creating "secret worlds of erotic kinship" (Lothian 2016, 744, 746), of making a space you want to inhabit. BobaBoard's ethics of world-making stresses not only care but also pleasure and fun (note 10); finding both, the users of BobaBoard have cultivated "social responsibility" and ethics.

7. Conclusion: Building spaces for belonging

[7.1] Emerging from a context in which fans draw battle lines over sexual fantasies present in media, and in which social media platforms censor depictions of sex, BobaBoard is collaboratively being built by its community, a "niche group of weirdos," to create a space where fans can freely share sexual fantasies and express themselves without fear of judgment or harassment. The creation of BobaBoard includes both code and culture: as a result, the whole BobaBoard community is involved in creating what the platform looks like. Thus, as one user wrote, there is a collective sense of "social responsibility" for the space that BobaBoard is and will become; as I was solemnly reminded when I signed up for an account, "you have real power to influence the developing culture on this platform." BobaBoard's users grapple with questions of what constitutes harm and how to protect people—in other words, questions of ethics. This goes beyond an "ethics of care" (Busse 2018, 5), however, into an ethics of "world-making" (Lothian 2016, 744): valuing pleasure as well as care, creating a space for "erotic creativity" (Rubin 2007, 171) and connection. Collective "social responsibility," or the ethics of the community, is key to the everyday functioning of BobaBoard.

[7.2] Two central means by which the community behind BobaBoard strives to achieve its goals are an anonymity-first design and an ethos of free expression and anti-censorship; as I learned, both approaches are intertwined with the "social responsibility" that BobaBoard's users foster. I encountered highly nuanced and considered perspectives on how to build spaces from BobaBoard's community, and the people I asked considered the potential benefits and potential drawbacks of both anonymity and free expression. As they explained to me, because the BobaBoard community is small and collectively promotes social responsibility, BobaBoard has largely avoided the drawbacks of anonymity. And from Damian's story of conflict resolution and my own experience with the tagging system, I learned how the dual principles of respect for others' fantasies and respect for others' boundaries allow BobaBoard to be a place where people can freely share their sexual fantasies while addressing conflicts that arise with minimal harm. The shared ethics of BobaBoard's users are thus key to making BobaBoard's goals a reality.

[7.3] BobaBoard's quest is ultimately to build a space of belonging for the outcasts, the "niche group of weirdos," the fans whose tastes and interests might earn them at best strange looks and at worst harassment and abuse from others, especially in the fraught climate of the fandom sex wars. This is the space of belonging that Ms. Boba spoke of wanting to create in her interview, the space of belonging that Damian has looked for but seldom found. Perhaps the "social responsibility" comes from an awareness among BobaBoard's users of this ultimate goal: for those who have looked for a space of belonging, it becomes every user's responsibility to continually cocreate this one. I use "continually" here because, as with all culture, BobaBoard's culture—its ethics and values—is perpetually in the process of being built and negotiated. This is especially apparent now, in the nascent stages of BobaBoard's existence, but the BobaBoard community (and future communities) will always be negotiating issues of censorship and anonymity. But at present? It is still early, but I think BobaBoard is succeeding in its quest. As I encountered the community, myself a fan who has sometimes struggled with fitting in, I found belonging and identification with BobaBoard's "niche group of weirdos. " I now proudly count myself as one of these weirdos. BobaBoard is and is becoming a space of belonging.

8. Acknowledgments

[8.1] I would like to thank Dr. Bambi Chapin for her patience, feedback, and endless kindness and generosity in her mentorship of this research, as well as fellow students for their support, camaraderie, and valuable feedback. I am grateful to the entire BobaBoard community, who agreed to let me undertake this project and welcomed me with open arms, and I would like to particularly thank Ms. Boba and Damian for their generosity with their time, as well as the other anonymous respondents to my questions on BobaBoard.