1. Introduction

[1.1] "We have some controversial/heavy themes going on, so be careful k? Do you know what sort of thing we have going on—were you warned" (note 1).

[1.2] With these words from one of its members, I gained access to a Discord fandom server in January 2021—one of two servers that I would visit regularly as part of ethnographic fieldwork taking place during the year that followed. Discord is a Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) and instant messaging platform where users can create and participate in servers dedicated to a shared topic of interest. Managed by administrators (admins) and moderators, Discord servers provide online spaces where groups can congregate and communicate via text chat, voice, or video stream and interact with community-created bots. Their size and accessibility vary widely, from private friend servers to publicly listed ones with thousands of members. Although developed as a community platform for gamers, Discord's reach has spread far beyond the gaming community. This particular server, centered around themes I was kindly warned for, was founded to create a safe space for fans to imagine, create, and share stories, artwork, and scenarios—kink-oriented and often sexually explicit—involving the characters from a popular Chinese danmei novel and its adaptations. Its members were glad to have found a closed environment with like-minded people for their imaginary endeavors into the worlds of BDSM, tentacle porn, and other kinks and tropes. I, in turn, was glad to have found a group who was willing to let me into their private space, after being rejected by several others, careful to protect themselves from having a researcher around (see Dym and Fiesler 2020).

[1.3] Discord's popularity among fans has been on the rise for several years. The platform provides the playing field for a range of activities common to fandom: users share and promote fan works, theorize about storyworlds and characters, ask for prompts and feedback on each other's work, organize and communicate about fandom events, and so on. Typical to Discord, however, is users' ability to do these things in private servers where access has been limited—which for fans means they can create fan spaces with limited outside interference. As the above response from a server member indicates, this ability holds the potential to facilitate the development of tight-knit communities centered around carefully guarded themes and practices. As a result, studying these closed spaces is challenging for researchers and raises many questions. What role does Discord play within the broader network of platforms popular among fans? How do fans navigate Discord as part of their fan practices? What does this mean for the ways in which fans experience fandom?

[1.4] In this article I aim to answer these questions by analyzing fan engagement on Discord through the lens of play. Despite Discord's rapid growth since its initiation in 2015, systematic, in-depth research into the platform is still in its infancy. With regard to media fandom, Discord has been discussed to various extents in relation to platform-oriented approaches (Alberto 2021; Floegel 2021); live streaming and privacy (Guarriello 2021); and specific practices like fannish bookbinding (Kennedy and Buchsbaum 2022). Because of Discord's position among other platforms and the types of practices that happen in fan servers, I argue that play theory offers a thus-far-unexplored yet valuable framework to understand how fans navigate the platform and build collective moods that keep them engaged for prolonged periods of time. I focus on two small-scale Discord servers in particular where fans are deeply involved in transformative works, which means that the scope of this study is necessarily limited. Yet qualitative, longitudinal research like this allows for a detailed and nuanced view of the activities and negotiations that happen in fandom spaces that are less public but central to many people's fan experience. Moreover, close analysis of Discord as a playground will further our understanding of play as a substantial driving force behind digital engagement as it takes shape in contemporary platform society.

[1.5] In what follows, I examine how a group of fans navigates Discord and tease out some of the specifics of what the platform contributes to their fan experience. Specifically, I focus on three prominent features of transformative fandom—boundaries and privacy, warnings and consent, and events and feels—and show how Discord has been adopted and adapted in relation to these features. I argue that Discord, more than other platforms, gives fans the ability to manage social boundaries and establish set-apart spaces where fans can remix and transform cultural elements in playful, sometimes transgressive, ways according to principles and norms important to their own (sub)communities. In addition, in ways both similar to but also different from other platforms, Discord allows fans to take part in and help create a powerful, collective play mood that they can keep returning to. Before doing so, however, I first elaborate on the importance of approaching Discord as part of a network of platforms, on what examining fandom on Discord through the lens of play contributes, and on the methodology used for this study.

2. Background and approach: Polymedia and play

[2.1] Fans traditionally have been early accepters of new online platforms. In their article on online platform migrations, Casey Fiesler and Brianna Dym (2020) paint a picture of the rise and fall of various platforms within transformative fandom. Defining transformative fandom as "the community constructed around people who create, share, and discuss fan works based on existing media" (2), they trace fandom's presence from Usenet and message boards in the 1990s to Tumblr and the Archive of Our Own (AO3) in the late 2010s. Relevant here is that their findings show, firstly, that fans make use of a variety of platforms, often concurrently. In Discord's case, for example, many fans find their way to servers by references made in user bios on Twitter or Tumblr or by receiving an invite from someone they know from another platform. Secondly, Fiesler and Dym show that fans have a high level of awareness of the policies, values, and affordances of different platforms and that these elements affect fans' decisions to stay on or leave a platform. This awareness has partly been born out of necessity: fan communities historically have had to deal with platform policy changes—often surrounding sexually explicit material—that disrupted communities and led to a permanent loss of fan works (see Fanlore n.d.; Floegel 2021).

[2.2] A number of studies have argued for studying platforms not as separate, singular entities but as part of a broader ecology of use (e.g., Miller et al. 2016). Mirca Madianou and Daniel Miller's theory of polymedia (2013) directs attention to the fact that people usually use more than one single social media platform and do so from situated contexts. They argue that media, platforms, and technologies exist as an integrated environment of affordances in which each medium is defined in relational terms in the context of all other media. Moreover, they note (2013, 172): "It is not simply the environment; it is how users exploit these affordances in order to manage their emotions and their relationships." For example, in interviews, my interlocutors explained Discord explicitly in relation to other platforms, noting how Discord is "more personal" than Tumblr, which "is a bit more of a public face" or how Discord offers "more of a relationship" rather than just showcasing your work, as "that's essentially my AO3."

[2.3] Affordances, from this perspective, concern more than stable, technological platform properties. Defined in relation to digital media as platform properties that shape participants' engagement and make possible and facilitate certain types of practices (boyd 2014), several studies have pointed out that affordances can be used in unexpected ways by users and be enveloped by social and cultural norms. Maria Alberto refers in this regard to cultural affordances next to technological ones, defining these as "practices and expectations that users set among themselves based on what technology makes possible, so these can change with time, pressure or new norms" (2021, 244). Elisabetta Costa (2018) coined the term "affordances-in-practice" to refer to the ways in which social media are intricately related to off-line everyday life, which involves different practices, everyday actions, and habits across social and cultural contexts.

[2.4] Play theory provides a helpful lens to consider Discord as part of a wider network of affordances that fans—who have a particular history with platforms—use in particular ways and settings to engage in fan activities. Navigating a platform is not the same as playing a game; however, in both cases users interact with and negotiate rule-based structures and designs. Moreover, the ludic has a strong presence in digital society, which includes people's engagement with digital technology and software (e.g., Sicart 2020). Fans, in this context, are exceptionally skilled players whose play practices can provide broader insights into how people relate to and navigate polymedia environments. In this article, I build on Line Petersen's (2022) conceptualization of fan play to analyze fans' engagement with Discord, focusing on two characteristics of play in particular: how playing can be productive of a powerful mood and its relationship to rules.

[2.5] Although various scholars have theorized fandom as a form of play (e.g., Hills 2002; Stein 2015; Booth 2017), Petersen (2022) centers the play in fandom fully. What most conceptualizations of play have in common (many of which are building on or critiquing Johan Huizinga's seminal Homo Ludens [1938]) is that they refer to either a cultural form (a play mode or game-like activity) or a disposition or mode of experience (a play mood) that is tied to the human capacity to deal with reality in a subjunctive manner (e.g., see Malaby 2007). Put briefly, this means people are able to imagine "as if" scenarios and navigate different qualifications of reality that can be recognized by some sort of boundary marking or "framing" (Handelman 2008). Petersen argues that fans take part in play modes through which they develop a skillset that enables them to produce and navigate play moods. Play moods result from participation in (digital) fan practices and are ways of "setting the tone" for participating in digital culture (Petersen 2022, 7) or ways "in which the player relates to the surrounding world" (34). This goes beyond the creation of transformative fan works (a very obvious mode of as-if and remix) and includes playful practices like creating and sharing memes, GIFs, blog posts, and tweets, turning social media platforms into the playgrounds where much fan play happens. Crucially, Petersen shows that it is the pleasure of engaging in play moods that draws people to fandom and that keeps them there for as long as the mood keeps going. "Fan play," she argues (2022, 34), "is its own reward. Being playful with other fans, diving in and out of play moods and modes, the pleasure and repetition of engaging with the same fan object over and over again or breaking with one play mood to invite another one in are meaningful in their own right." Though play moods may not always relate to pleasure (cf. Trammell 2023), they are powerful and can draw people in.

[2.6] The navigation of play rules is essential to the creation of and engagement in play moods. Such rules create the frame that defines the boundaries of the playground (where the play starts and ends) and invite people to play. Rules provide structure by creating both limitations and possibilities in the form of prohibitions and potential, meaningful action (Juul 2005, 58). Experimenting within but also with the rules is one of the things that make play so alluring. As Miguel Sicart puts it (2020, 2084): "To play, and to be playful, is to explore the pleasures of breaking or submitting to rules and boundaries, of obeying and disobeying them." Petersen builds on such theories to distinguish among three types of play rules that fans navigate across platforms and that shape fan play (2022, 53): infrastructure rules, authoritative rules, and conventional rules. Infrastructure rules are underlying formal structures that shape the play experience, such as code, affordances, and media logic. Authoritative rules are imposed top-down and involve platform terms and conditions, national laws, industry-imposed rules, and the diegesis of a media text. It also includes written-down group rules, such as community guidelines instated by moderators. Conventional rules are the usually unwritten etiquette and norms of a community or a broader societal context. Analyzing these play rules and how fans navigate them as part of their play in the context of Discord may help to identify what Discord affords fans and what it is fans do with these affordances, as well as how this contributes to the creation and continuation of play moods. In short, this means that to understand what makes Discord so attractive to fans is to understand what play rules are established and negotiated on the platform, in relation to other platforms, and how they result in play moods that are compelling and meaningful to fans.

3. Methodology

[3.1] The data this article is based on was gathered during ethnographic research for a larger project aimed at understanding the place and meaning fandom has for fans of fictional media (primarily books, films, and TV shows) in their everyday life. Fieldwork was conducted from January 2021 to 2022 and included participant observation in two private Discord fan servers and on fan accounts of twelve individuals, eight of whom use Discord as one of several platforms to participate in fan activities. Most of these individuals also took part in semistructured interviews over video calls. The interviews included a media go-along (Jørgensen 2016) where participants gave an online tour of their social media accounts, including Discord and servers they were in, via screen sharing or by holding their phone up to the camera.

[3.2] The longitudinal nature of ethnography and its reliance on key informants allow for a level of trust to develop between the researcher and the people they study and enable a deep understanding of the culture, norms, and patterns of a group, which was especially valuable in researching private Discord servers. The individual fans that took part in this study were active in various fandoms and used a variety of platforms to engage in fandom—primarily Tumblr, Twitter, AO3, and Discord. Participants were recruited via a survey and via snowball sampling. Those who used Discord were between twenty and thirty-three years old, the majority of them white women living in the United States. Through them, I obtained informed consent to access two fandom servers to observe participants' activities in context and observe and take part in conversations and events: the server mentioned in the introduction (server A), with around sixty members at the time of fieldwork, and another server (server B) that belongs to a preexisting fan fiction community centered around specific works of J. R. R. Tolkien, with around 300 members. Research data was coded and analyzed iteratively, based on the interplay between induction and deduction (Hennink, Hutter, and Bailey 2011). Coding took place in ATLAS.ti, using deductive codes derived from polymedia theory and play theory (like affordances, framings, and play rules), as well as inductive codes developed from the data itself. The former helped sensitize toward issues within the data; the latter informed the focus on the three features discussed below.

[3.3] In the remainder of this article, I examine Discord as a playground structured by rules and the movement between them. Specifically, I focus on three features generally important to transformative fandom: (1) boundaries and privacy, (2) warnings and consent, and (3) events and feels. I show what infrastructure, authoritative, and conventional rules are present in relation to each feature, how my interlocutors navigate these rules, and how these navigations shape fan play and help create and maintain play moods.

4. Discord as a playground: Boundaries and privacy

[4.1] Privacy is an essential consideration for many fans, especially those engaged in fan practices with a history of stigmatization (Dym and Fiesler 2018; 2020). This is not simply about denying or providing information; privacy involves ongoing, active boundary management and the negotiation of contexts in a polymedia (what Marwick and boyd have called networked) environment (2014). Online spaces like the Discord servers discussed here are therefore not inherently public or private; they are shaped by privacy strategies employed by individuals that depend on the technical and social regulation of affordances, social norms, and cultural context.

[4.2] There are several factors that make privacy strategies important to fans. Firstly, many fans want to keep a level of separation between their fan identity and other domains of life. As one interlocutor noted in an interview: "Outside of these [fandom] spaces, like there is so much explanation you need to do." This is exemplified by the use of pseudonymous usernames and the creation of fan accounts disconnected from other (nonfannish) social media accounts (see also Gerrard 2017). Secondly, within fandom, not all practices and fan works are accepted. Fiesler and Dym (2020, 15) describe how subgroups within transformative fandom often have their own norms and values and how recent fandom migrations have resulted in increased conflict between these subgroups. Although certainly not without strife, before the 2010s, platforms like Usenet and LiveJournal allowed for a certain level of self-containment and moderation within subgroups. Since the early 2010s, however, fandom has become increasingly centralized, finding a home on platforms like Twitter and Tumblr. Consequently, different norms and values of different groups run a higher risk of clashing, for example resulting in ship wars and anti/pro-ship debates (see TWC Editor 2022). Thirdly, the policies of commercial platforms can form hostile environments for fans, as in the case of LiveJournal, FanFiction.net, and, more recently, Tumblr, all of which have reinforced bans on (certain) sexually explicit materials and cracked down on accounts and works supposedly violating these bans.

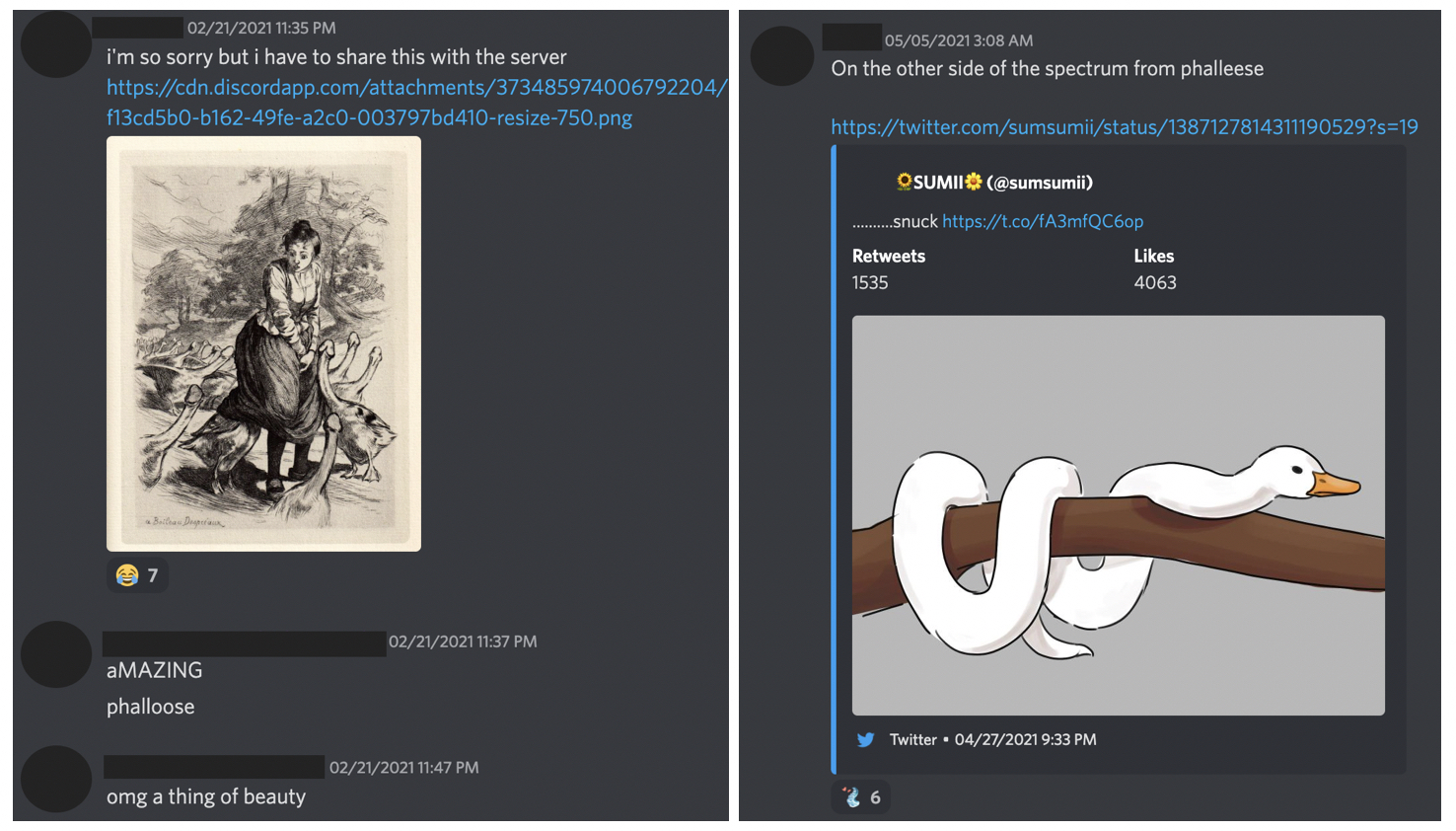

[4.3] In these circumstances, the ability to erect and negotiate barriers continues to be important for many fans. Take the following example from server A (figure 1). In the left screenshot, a member shares a drawing they found elsewhere. In it, a woman with a somewhat surprised look on her face is gripping her skirt while geese with penises for heads are trying—and succeeding—to get underneath it. No further context was given, but other members in the server quickly chimed in with statements such as "aMAZING / phalloose" (using two forms of language play by capitalizing specific letters and combining the words "phallus" and "goose") (note 2) and "omg a thing of beauty." In another server channel, three other members started speculating about the biology of the creatures ("What if they don't have any eyes at all? I am kind of enthralled at the idea of these phallic creatures just sensing their way around by scent and sheer sex drive…" and "There can be several species of them with different degrees of supernaturality! They can coexist!"). Soon, the server had established a solid lore surrounding the "phalleese," creating different scenarios of the creatures having sex in various ways with fictional characters. Months later (right screenshot) members still played with the phalleese, also involving materials from outside the server (like unrelated tweets) in their play.

Figure 1. Play happening in server A. Note that the message in the screenshot on the right is dated several months later.

[4.4] Open-ended play like this, which emanates a sense of joy and creates a mood that is carried on by community members over time, is one of the things that makes taking part in fandom so compelling. At the same time, it is why most people would rather not connect their fan practices to their real name or social media accounts where everyone, including colleagues or family, can see. Some people would even opt to keep this separate from their main fandom accounts due to possible associations with bestiality. The fact that much fan play involves sexually explicit or otherwise NSFW material makes privacy and boundary negotiations even more important. Moreover, there is a level of absurdity going into much of the play that is part of what makes it fun but also part of what makes it so difficult to explain to outsiders. And, as with so many jokes, having to explain it may very well take the fun out of it.

[4.5] Dym and Fiesler (2018) mention Discord specifically as a platform where fans have created strategies for dealing with a lack of privacy control elsewhere. Discord's infrastructure rules fit well with fans' wish to manage who to let in (and to what extent) on what it is they do online. For example, while content from other platforms often gets shared on Discord (like the tweet in figure 1), Discord does not have affordances that facilitate easy content distribution from servers to other platforms, contributing to the perception that the platform is more closed than other popular platforms. Even more important in this regard has been the affordance to create server invitations. Once someone has created a Discord server, they can use the invite function to invite Discord friends or create an invite link that enables new users to enter the server. For this, different settings can be selected; for example, the link can be shared publicly or only by certain members, the link can expire after a certain number of days, or it can only be used a limited number of times. This allows people to manage the accessibility of their servers.

[4.6] There are various authoritative rules and conventional rules surrounding the invite functionality, revealing the active implementation of privacy strategies shaped by social norms and context. Due to the nature of server A, which according to its admin is "both exciting and mortifying for our members," the creation of boundaries has been essential for the community to flourish. Members are not necessarily secretive about the server's existence, but an invite link is conventionally only given out to fellow fans whom existing members already know from previous interactions over other platforms or other Discord servers. Although no official rules were set in place, both admins and moderators have posted messages outlining how to engage with the server and one another, which includes rules as to who can be invited: anyone who is interested in the topics discussed on the server, except for people with a history of behavior deemed unacceptable by the community, such as bullying, dogpiling, or stealing fan fiction ideas. Such strategies also appear in stories from other interlocutors. One of them explained to me how, when fellow fans request an invite link from them (usually via Twitter or Tumblr, where admins often mention in their bio that they are a server admin), they and other server moderators first explore said person's social media to check if they "fit in with like, our attitude where, you know, are they cool with NSFW content (…) are they open-minded enough to be like: alright, these are all fine things to discuss."

[4.7] In server B, centered around Tolkien's work, the moderators removed a permanent invite link from the community's website after they felt this got abused by new members who refused to adhere to community guidelines. An invite link now has to be requested from the moderators or only becomes accessible after registration. Because it is important to the community to push back against gatekeeping in the larger Tolkien fandom, server members are allowed to generate an invite link and invite new members, as long as they agree to stick to the rules. During live events, such as fan fiction live-readings, a temporary open invite gets issued via the community's social media channels. As stated in the read-me-first channel of the server, members should consider the server to be "semi-public" because of the number of people in it but a "private server" nonetheless. In addition, there are two other guidelines that emphasize the boundaries between the server and other online spaces: it is forbidden to publicly share another member's identifying or contact information against their will, thus maintaining separations between fan identities and other identities of server members; and it is forbidden to import drama or conflict from other platforms into the server.

[4.8] If managed well, Discord servers provide their members with a conflict-free space to enjoy and explore their fandom together, where play moods can be created and maintained. This involves ongoing management from administrators, as the threat of malevolent intruders always lingers. Infrastructure rules regarding Discord's invite functionality allow those responsible for servers to set a threshold for entering and provide a framework for authoritative and conventional rules to develop. These rules actively reinforce negotiated boundaries and create fan spaces that feel more closed and private than the centralized (fan) spaces of Twitter and Tumblr. Importantly, fans do not generally migrate to Discord: rather, they add it to the network of platforms they already use as a space where there is a higher level of privacy control and, because of that, an increased opportunity to play more freely, transgressively, intimately, or safely with other fans, without judgment or interruption from outsiders.

5. Discord as a playground: Warnings and consent

[5.1] Content warnings and consent are important to transformative fandom. Fan fiction in particular has a long history of using systems of warnings to create a kind of contract between author and reader—a set of play rules that establish the limits of the story and invite exploration within said limits. For example, authors are expected to use content warnings to signal to readers what they can expect in a story, which gives readers the responsibility to make informed decisions about whether or not to engage with particular works (Busse 2017, 206–7; see also Popova 2021). Online, this may translate into affordance infrastructure directly, like how authors on the fan fiction website AO3 are required to add archive warnings and tags to their work.

[5.2] On Discord, similar structures are created and negotiated by fans. Infrastructure rules and authoritative rules, such as technological affordances and Discord's terms of service, create limitations and open up possibilities to fans to navigate and structure server spaces and practices in ways that align with norms and values that have developed in fan culture on other platforms. This also shapes conventional rules in the servers. Here, I focus on rules surrounding server channels and user roles. In servers, admins and (if permitted) moderators are able to create channels: dedicated "rooms," usually focused on a particular topic, where people can communicate. Channels are listed in the left-side bar of a server and appear in contrasting color when they contain unread messages for a user, making it easy to see where activity has happened while off-line. Users can also mute channels, so as to not receive any notifications on them. User roles can be given to users to create different subgroups within a server and determine their appearance (primarily through color coding) and permissions: what they can see and do in a server. For example, a user can be given the role of moderator, which allows them to perform actions and access channels that users without the moderator role cannot.

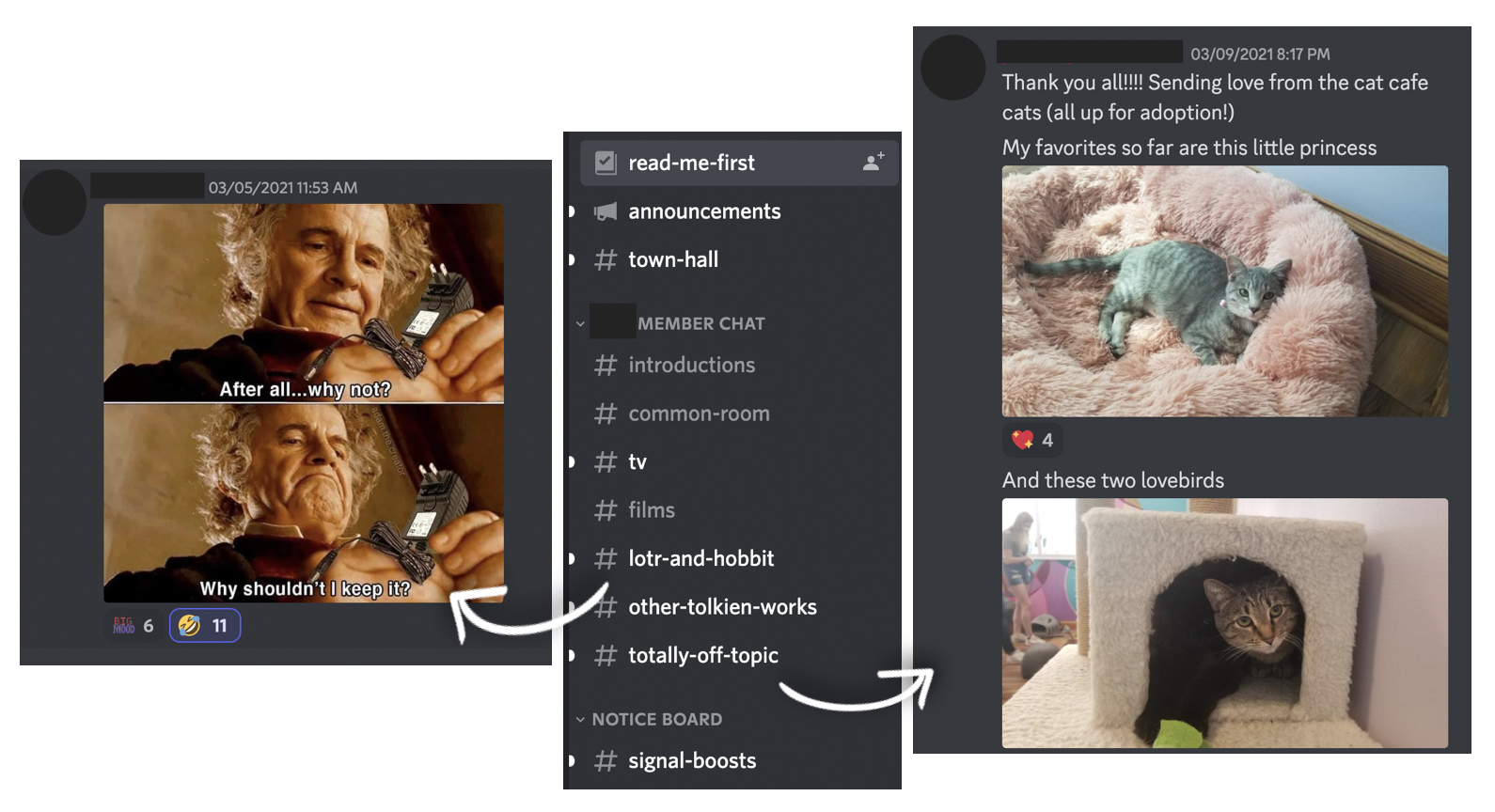

[5.3] Managing rules surrounding channels and user roles enables server communities to create boundaries between play and nonplay and navigate warnings to ensure consensual, safe play for all members. Firstly, in servers, members generally keep conversations about specific topics contained to their designated channel(s). This is partly an organic result of the division of servers into channels, but remaining on topic is also an imposed, authoritative rule reinforced by moderators: moderators step in and ask members to move to a different channel if they discuss a subject or post content not belonging to a channel's topic. Through these rules, distinctions arise between channels for fandom-related topics—where fans play—and channels where fans chat about nonfandom-related issues, such as everyday events. Figure 2 shows how in server B, boundaries are drawn between channels where fans discuss a variety of fandom-related topics and engage in playful activities (e.g., discussing canon, exploring fictional scenarios together, creating and sharing memes) and a dedicated "totally-off-topic" channel where members go to chat about subjects not related to fandom. This channel usually sees daily activity, ranging from very mundane messages about food or pets to more serious ones about personal struggles or life events. By keeping such conversations confined to an off-topic (i.e., nonfandom) channel, fans reinforce the boundary between play and nonplay. Like with other warnings, this division signals where the play begins (or is ongoing) and where it ends.

Figure 2. Some of the channels in server B, with a dedicated channel for nonfandom-related off-topic interactions.

[5.4] Secondly, channels are used to set up warnings around particular types of play, most notably involving NSFW material. Server B has two designated NSFW channels where members are allowed to discuss (fan works focused on) sex or subjects that are considered dark, like graphic violence. This enables members to deliberately opt for engagement with these topics—engaging and disengaging with transgressive or societally taboo forms of play and moods only if and when they want to. Server A, being centered around kinks, is mostly NSFW throughout. Yet here, too, different play rules have developed to ensure members can engage in ways that are safe and that do not disrupt the pleasure or excitement many of them gain from playing. During the period of fieldwork, many discussions took place among admins and members about where people should chat about which subjects or scenarios. Consequently, the server has come to host a wide variety of channels, each dedicated to a specific kink, trope, or character pairing or relationship. Like in server B, members are expected to adhere to the designated channel topic, a conventional rule that enables everyone to mute channels and/or circumvent subjects that are visceral turn-offs (squicks) or triggers to them. Members are quick to point out misplaced messages, which usually results in an apology and correction by the person having made the mistake. And when in doubt or when a kink has not yet received its own channel, people are asked to consult an admin.

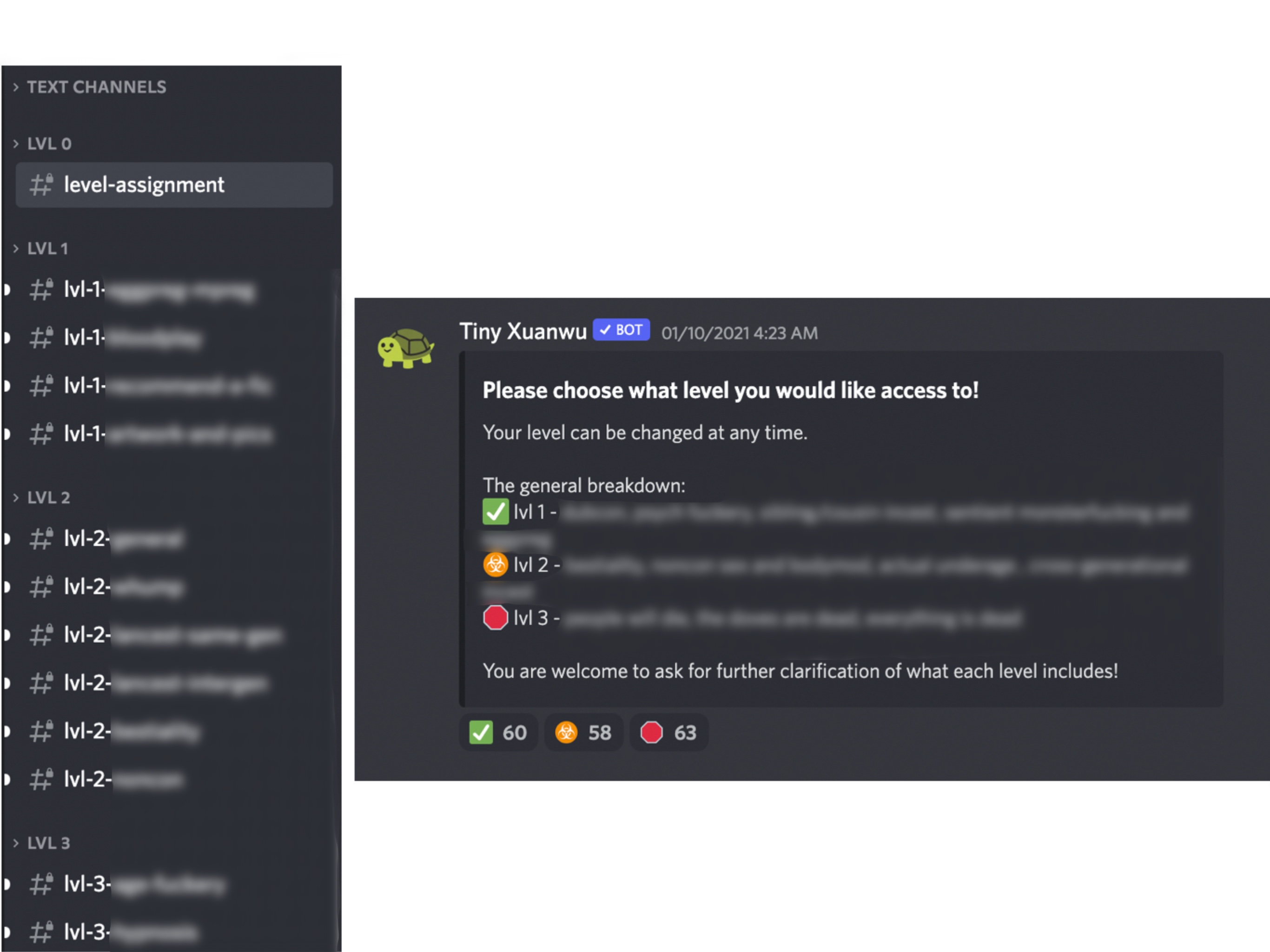

[5.5] In addition, server B has created extra layers of security through a four-layer level system using the affordance of user roles combined with channel organization. This system reveals how infrastructure rules allow for creative interaction and adaptation—for playing with the rules to enable risky yet safe play. As mentioned earlier, Discord affords the creation of user roles to establish subgroups within a server. Different roles can be given different permissions, including access to channels closed to other roles. Channels, in turn, can be grouped in overarching categories (like "member chat" and "notice board" in figure 2), which (among other things) allows for easy exclusion or inclusion of specific user roles to subsets of channels. In server A, the community has used these affordances to create levels with strict authoritative rules (figure 3). By selecting a level role in the Tiny Xuanwu bot (done through clicking on the accompanying emoji), members can give themselves access permission to the different levels in the server, deciding for themselves if they want to keep to the lower levels or if they want access all the way up to the playfully named "problemattic." Key to this system is that members are required to chat about specific subjects only in the appropriate level. For example, scenarios involving dubious consent belong to level 1, while especially dark tropes involving nonconsent belong to level 3.

Figure 3. Channel division and roles for the level system in server A.

[5.6] The rules discussed in this section—infrastructural, authoritative, and conventional—are navigated and negotiated by fans based on what works for them and what they know from experience and practice on other platforms, like AO3 and other archives that work with content warnings and tagging systems. Importantly, the examples presented here reveal how rules invite creativity, open up possibilities, and show fans "teasing out playful potential by using affordances in subversive ways to engage in play moods with other fans" (Petersen 2022, 64). It is through the creation and ongoing negotiation of play rules that fans are able to distinguish between play, nonplay, and different types of play—a prerequisite for play moods that bring pleasure rather than discomfort. This includes the engagement—or rather lack thereof—with authoritative rules such as Discord's terms of service. Whereas Discord's policies state that admins are required to apply an official age-restricted label to "any channels or servers if they contain adult content or other restricted content such as violent content" (Discord 2022), such labels are not ones fan communities will be quick to take up, especially considering the conflicted history many communities have with commercial platform policies (note 3). They are more likely to devise their own ways to ensure safe engagement with particular types of content.

6. Discord as a playground: Events and feels

[6.1] Fandom events are an integral part of the broader fandom landscape, from small community-based events to big multifandom ones with hundreds of participants. This last section focuses specifically on fan fiction exchanges. In keeping with fandom's gift economy customs (Turk 2014), fan fiction exchanges are structured, ritualized, almost game-like events in which fans gift fan fiction (and sometimes fan art) to one another based on sets of prompts, tropes, or suggestions. Often, the gifter remains anonymous to the giftee until the moment all works and authors are disclosed (aptly named "reveals"). Many exchanges have a long history and return on a yearly basis, being hosted on various platforms concurrently. For example, AO3 has affordances built for fans to manage fan fiction collections for exchanges. However, because AO3 is primarily an archive and not a social media platform, event organizers usually employ other platforms like Tumblr, Dreamwidth, and email to promote the event and manage communication. Increasingly, this list also includes Discord.

[6.2] The negotiation of play rules on Discord adds a frame of liveness to fan fiction exchanges: a sense of social copresence that comes with specific expectations (Auslander 2022, 32–34). This frame creates a contagious atmosphere and heightens play moods during exchanges in ways other platforms do not or only limitedly provide. In terms of infrastructure rules, servers A and B both use channels to create set-apart spaces for exchanges, with each exchange receiving its own channel. For most of the year, an exchange channel is quiet, almost invisible against the background of the server's channel display. However, once organizers start to promote the exchange, its channel comes alive. As people start posting in it, its name in the channel display changes color, the sudden visibility (re)materializing its presence and kick-starting the play mode. Members flock together to express their excitement and ask questions, resulting in a flurry of activity that continues for the duration of the exchange.

[6.3] Discord enables members to chat with each other synchronously, in real time. Although Discord is known for its voice channels, where users communicate via audio, interaction in fan servers primarily takes place via text chat. Despite this being technically asynchronous, with affordances like a high persistence of transcript that allow for older messages to be found and read at a later time, it also allows for chatting in real time. Fans gladly make use of this during exchanges. For example, channel activity peaks nearing deadlines (e.g., when people need to hand in their list of prompts and "do not wants" or post their gift) and during reveals, the event's climax. During these moments, people log on together to excitedly (and often anxiously) watch the clock tick down. In the events I observed, hundreds of messages were posted in the span of a few hours, with people double-checking time zones to make sure they were on time to witness reveals and others expressing disappointment when they had to miss out due to other obligations. This creates a heightened play mood, as the example below shows.

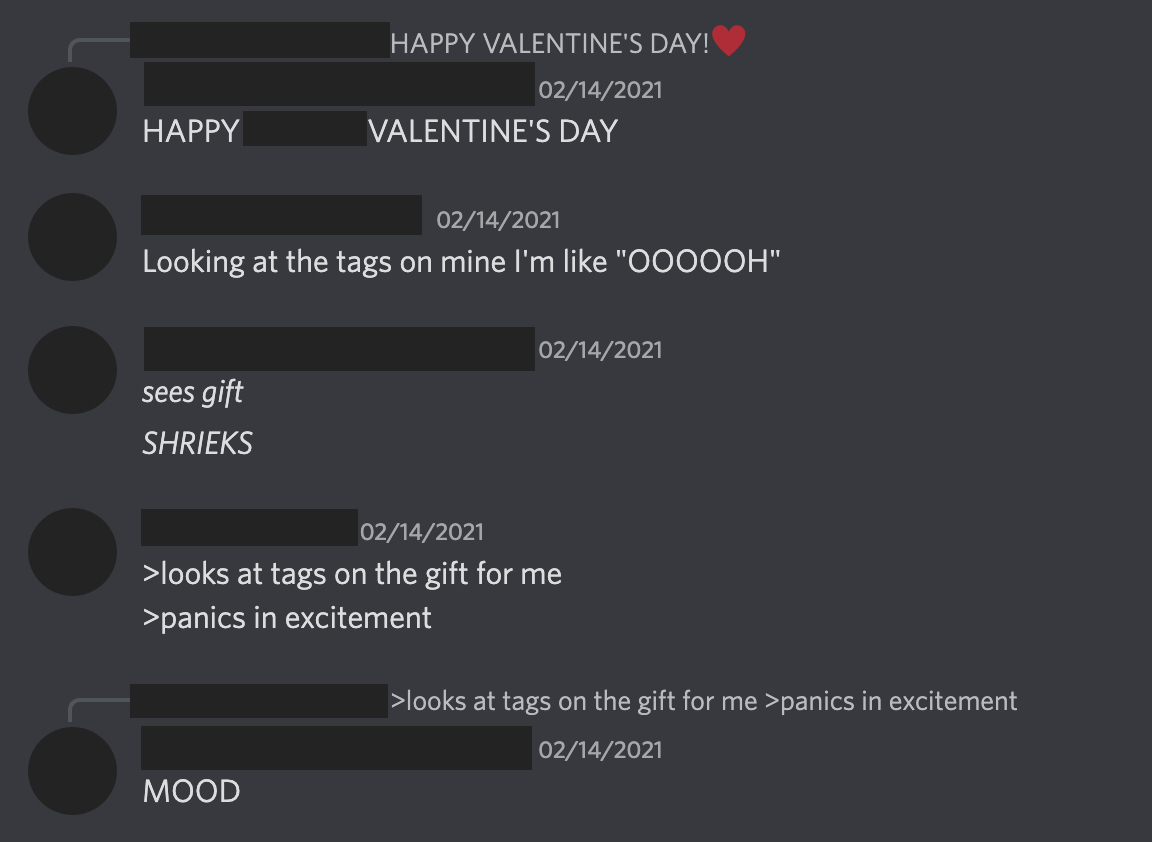

[6.4] Figure 4 shows an example of what the excitement at the moment of reveals looks like. Importantly, this exchange of shrieks and panicked excitement is not simply a response to what people feel, nor is it only shaped by infrastructure rules. Rather, how people express emotion and create a play mood is highly performative and steeped in conventional rules. The messages display a public expression of emotion or performance of feels (Stein 2015) by server members that establishes mood in the room—even explicitly so ("MOOD"). One of my interlocutors was part of this interaction. Once she had read her gift, she posted happy messages in the event channel and an excited comment to thank the author on AO3, where all gifts were published. This comment included capitalized statements like "OMG I LOVE," enthusiastically screaming ("aaaaahhh!!"), and references to happy "shrieking" when reading the fic for the first time. It did not in any way reveal that in fact she was quite disappointed with the gift, which was written in a style she usually would not pick up to read. However, she explained, expressing disappointment would not be fair to the author, who obviously worked hard on the fic. In other words, it is not what a good sport would do. Similarly, when someone in the event server channel did express disappointment, in this case because of radio silence from their giftee, this created a sudden tension in the room. Other members were quick to point out that they have had similar experiences in the past, empathizing with the member in question, who in turn apologized for dampening the mood. There are, in short, ways in which one is supposed to (re)act and ways in which fans negotiate emotions as part of their collective mood work.

Figure 4. Interaction between server members at the moment of reveals of a yearly Valentine's fan fiction exchange.

[6.5] Understanding fan fiction exchanges as ritualized events that evoke a collective play mood may also help to explain why the authoritative rules that surround exchanges are so prominent. Exchanges are fundamentally structured and formalized, which helps set the stage for play modes to develop and enables the production of a collective play mood. A team of moderators sets up information pages, promotes the event, matches participants, and establishes and reinforces rules on minimum word count, deadlines, general etiquette, and how to fill out the suggestion forms for gifters (the latter also being informed by conventional rules), all of which enables exchanges to exist. Moreover, authoritative rules help in minimizing the risk of play moods being disrupted. For example, when issues arise or conflicts occur, moderators step in and ask participants to reach out in private to solve the issue, regulating the pain and disappointment that may accompany play.

[6.6] The structured, rule-based nature of exchanges and the ways in which emotional performance is regulated reveals something about how fans navigate mood. It shows how emotional performances are in part exactly that: performative. The power of the exhilarated play mood that fans tune in for asks for performances that maintain said mood or quickly establish a new one—one does not want to be a spoilsport. The play mood, then, is an important performative part of the ritualized event, reminding of the collective effervescence ritualized events are so good at invoking—for better or for worse (e.g., Berger 2015). In short, in the context of fandom events, Discord offers a confined space in which participants can congregate and share, live, in the experience of taking part, building a powerful, compelling, recurring mood together.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] In this article I explored how Discord is positioned in a larger network of platforms that fans navigate and what it affords fans from this position. I do so based on ethnographic research, offering an example of how longitudinal fieldwork, with its reliance on building relationships with and through key informants, can help in studying the communities, norms, and patterns that develop in closed online spaces like private Discord servers. Specifically, the article focused on three features of transformative fandom and how play rules, providing structure by setting up both limitations and possibilities, are navigated in relation to these features. Boundaries and privacy are important to fans to protect their identity as well as to ensure the pleasures of playing freely without outside disruption. In the context of an increasingly centralized platform ecosystem, Discord allows fans to erect and negotiate barriers and manage access to online spaces, building in a higher level of privacy control, which is especially important to those involved with NSFW material. These spaces can be organized in ways that adhere to established fandom norms concerning warnings and consent, with creative adaptations like the level system of server A, and channel divisions that separate fannish play, transgressive play, and ordinary life. In addition, Discord provides an extra dimension to the experience and sociability of taking part in fan fiction exchanges. Through their practices, and enabled and maintained by the ways Discord gets used and adapted, fans are able to (re)establish powerful, collective moods in servers that they can continually come back to.

[7.2] This study is limited with its primary focus on how fans involved with transformative fan works navigate Discord as part of their fan practices. Moreover, it is based on observations among and interactions with a small group of interlocutors and two servers in particular that are centered around fan fiction and fan art. Discord can work in other ways for other fan communities, including those involved with other kinds of transformative practices, such as role-playing. Furthermore, although the experiences shown here are largely positive, and the ability to create private servers on Discord is considered an asset by my interlocutors, this should not make us overlook its potentially toxic applications (Heslep and Berge 2021) and its tendency to uphold long-lasting inequities in fandom, such as structural racism (Floegel 2021). The fact that much power lies in the hands of admins and moderators also points to potential power dynamics and hierarchies different from those studied in more centralized fandom spaces. Herein lie possibilities for future research.

[7.3] In conclusion, examining Discord through the lens of play and polymedia shows how the platform has been adopted and adapted in ways that facilitate fan play and allow for collective play moods to be created, strengthened, or maintained. These insights also show how play rules, theorized as central to play, develop within the context of a wider polymedia environment in which boundaries and rules are complex, multilayered, and constantly (re)negotiated by play communities. Play rules and the limitations and possibilities flowing from them, rather than being superimposed, result from players' movements between, with, and against these structures. It is the players who creatively carve out a space for themselves on the platform, which fuels a playful disposition that drives their digital engagement. More generally, then, considering platforms as playgrounds provides a framework for understanding the reciprocal and dynamic relationships among users, affordances, rules, and structures in contemporary platform society.

8. Acknowledgements

[8.1] Many thanks to Line Petersen and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable commentary on earlier versions of this article. I am also very grateful to my research participants and the server communities and their admins who granted me access to follow along for a while. This research was made possible by funding from the Dutch Research Council and has been approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Religion, Culture and Society, University of Groningen.