1. Introduction

[1.1] In a 2010 online posting, Dan Haggard commented on the Twilight fan's fascinating place in popular culture: "The Twilight fan is interesting because of reports (however well substantiated) of a degree of extremism that goes beyond what is acceptable, even when considered from a perspective relative to standard fan obsession. The point here is not so much whether Twilight fans are any more extreme than standard fans, but that there is a perception that they are so." Much of the public commentary on the popular series and its intense female fans cyclically hits a high point during the release of the franchise's latest film, when Twilight fan activity is thrust most glaringly into the limelight, and this public commentary seems focused on trying to explain the "crazy" fan phenomenon to "normal" outsiders.

[1.2] Unfortunately, these explanations generally only consist of describing the series' frenzied and excessive female fans, of reporting the decibel levels of its fangirls' screaming, and the incredibly high number of movie tickets sold. Indeed, until the recent release of the final Harry Potter film, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, on July 15, 2011, the Twilight franchise boasted top box office records for both largest opening day gross, with New Moon (2009), and greatest midnight ticket sales, with Eclipse (2011) (Finke 2011). But despite such success, the series, adapted from Stephenie Meyer's young adult novels about the romance between human teenager Bella and vampire Edward, and the activities of its mostly female fans are still somehow seen as culturally dismissible and described, as Melissa Click (2009) points out, in terms of belittling "Victorian era gendered words like 'fever,'…'hysteria'" and "rabid." However, the realm of female fandom, and indeed antifandom, whether Twilight related or not, is much more vibrant and complex then these simplistic pop culture accounts of emotional women.

[1.3] I am concerned here with the specifically articulated identity of one online group of Twilight antifans, the Anti-Twilight Movement (ATM) (note 1), not with Twilight itself. It will examine this group's representations of and responses to the Twilight books, fans, and antifans, as well as the ways in which such articulations interact with the dominant cultural hierarchy. The antifans of ATM have constructed on their Web site, in opposition to themselves, a rabid identity of excess and irrationality that mirrors the characterizations often seen in popular descriptions of Twilight's female fan base and which they apply to both Twilight fans and antifans, both male and female. ATM antifans have created a Web site that allows them to express and perform their main antirabid and anti-Twilight-as-literature positions by criticizing the hostile and emotional antics of rabid Twilight fans and antifans and by carrying out their own literary criticism of the Twilight novels. In so doing, ATM is perpetuating accepted cultural notions about the superiority of the reasoned, the academic, and the elite, as well as of the inferiority of the popular, the emotional, and the feminine; it does so in hopes of rendering its own antifandom safe from similar cultural censures.

2. The Anti-Twilight Movement

[2.1] The Anti-Twilight Movement's Web site functions like the writings of the fans of cult films that Mark Jancovich (2002) discusses, similarly working to "produce a sense of subcultural identity, but also…seek[ing] to construct identities through the construction of an inauthentic Other" (306). The site also functions as the billboard of their antifan identity and is therefore meant to clearly inform every potential visitor, whether fellow Twilight antifan, devoted Twilight fan, or casual passerby, of exactly what type of antifan ATM is and precisely what type they are not (Grossberg 1992, 57). ATM's site expresses and reinforces the two core positions of its particular antifandom: first, its stance against fans or antifans who act so rabidly that they lose the ability to tolerate opinions that differ from their own or to carry out rational thought (ATM sees this as a problem particularly, though not exclusively, endemic to the popular Twilight franchise and its mostly young female fans); and second, its opposition to the claim that the Twilight saga is good literature, which it feels compelled to voice because of the popularity of the books and the uncritical devotion of its fans.

Figure 1. Screen capture of the Home page of the Anti-Twilight Movement's Web site, showing the pages of their site and their opening Welcome message that informs any visitor of ATM's specific antifan positions. (http://theantitwilightmovement.webs.com/home.htm, 2010) [View larger image.]

[2.2] ATM's Welcome message establishes both of these positions right away: "We don't like Twilight. It's poorly written…and the books just don't appeal to us. But if they appeal to you, that's fine…If you're a rabid fan, you probably won't understand that this site is specifically a critique site full of only opinions and observations and a helluvalot of dry humor." This opening welcome to the site lays out ATM's antifan positions and sets the stage for a stance of rational tolerance toward unrabid Twilight fans and a tone of dark, sarcastic humor. The site is composed of pages that either informatively state these two positions or extensively back them up. The Home, About, Links, and FAQ pages describe ATM's specific antifandom positions, and pages like Books and Ragemail contain the group's supporting evidence against Twilight as good literature and against the rabid fans and antifans of the franchise.

[2.3] Throughout the site, it is clear that the ATM antifans see themselves as having taken some sort of proverbial high road, or as being some of the few people associated with Twilight who are even capable of doing so. The ATM site, with its clearly qualified brand of antifandom, is meant to function as a sort of beacon for other like-minded Twilight antifans, those whom they believe will appreciate their arguments and be similarly capable of taking that high road of rationality and tolerance. ATM's belief in its own superiority permeates the site's critique of the Twilight books and of its rabid followers; this is expressly manifested in ATM antifans' own claimed logical faculties, their declared ability to overcome emotion, and their assessment and performance of appropriate, rather than rabid, behavior. This sense of superiority can specifically be seen in their professing to be performing some sort of social duty, their rejection (and labeling) of so-called immature fans and antifans, their shaming of other Twilight sites and groups that they feel act inappropriately, and their pointing out the spelling and grammatical errors of rabid Twilighters. All of these inferior-asserting descriptions inherently work to elevate ATM's own stated positions and make ATM members seem intrinsically superior to the rabids they are condemning, those who "take Twilight much too seriously" and who "can't react civilly to opposing viewpoints," as the site claims.

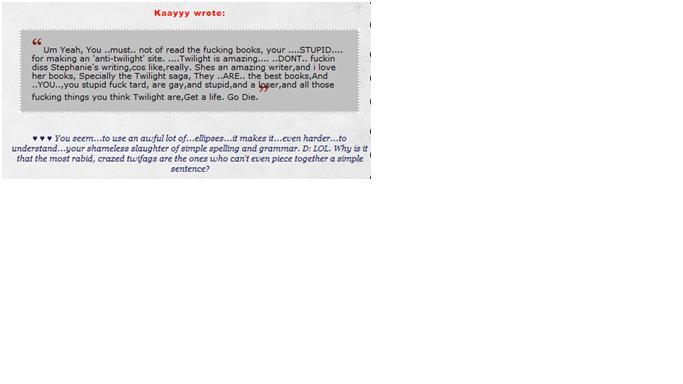

[2.4] The ATM admins rhetorically address these "rabid Twitards" on their site in tones of flippancy and sarcasm, as when they mock the emotional hostility of a hate message they have received or note that the rabid fan in question misspelled "Twilight" in her hurry to insult the ATM admin. This use of deflective humor is meant to show their own mental dexterity and to reinforce their earnest attempts to prove themselves capable of objectivity and of "safely" engaging in their own Twilight antifandom. In a way, the "dark humor" of their site, as they call it, is meant to temper their hate of rabid Twilight fans and the books' popularity, somewhat like Gray's (2005) posters on the Television Without Pity Web site. By using humor, ATM can seem less hostilely emotional and less subjectively hateful than if they had directly attacked every rabid they quote on their site.

Figure 2. Screen capture of one of the rabid fan messages in ATM's Ragemail, followed by their own commentary that directly addresses the rabid in question and sarcastically critiques her writing capabilities. (http://theantitwilightmovement.webs.com/mailbag.htm, 2010) [View larger image.]

[2.5] Unlike the Twilight antifans that Catherine Strong (2009) examined in the Cracked discussion forums, ATM does not communicate or function predominantly in chats and discussions, but instead articulates its specific antifan identity through the stable pages of its Web site. ATM also affiliates itself with certain anti-Twilight sites, like Twilight Really Sucks (TRS; http://twilightreallysucks.webs.com/index.shtml), which it sees as commendably similar to itself. ATM posts the list of these sites to their home page in order to facilitate the type of Twilight antifan discussion and expression of which it is a proponent and embodiment.

[2.6] As briefly mentioned before, ATM includes Ragemail from both rabid Twilight fans and rabid Twilight antifans on its site as apparently empirical proof of what ATM claims to be the aggressive and emotionally rabid behavior of the fans and antifans who engage inappropriately, as ATM sees it, with Twilight. This Ragemail works to prove, and subsequently justifiably vilify, ATM's construction of rabids as hostile, illogical, and emotional. In these sections, ATM administrators post the hostile messages they receive from angry Twilight fans and antifans, out of context, followed by their own disciplinary commentary, retaining and criticizing all spelling and grammatical errors from the original angry texts and e-mails. However, it is important to acknowledge that this is merely ATM's characterization of rabid Twilighters and that these messages do not represent the full range of Twilight fandom, rabid or not. It is entirely possible that ATM receives messages other than this rabid Ragemail that contradict or fail to fit its portrait of the rabid fan, and that therefore ATM does not post.

Figure 3. Screen capture of the Ragemail section on the Anti-Twilight Movement's Web site. (http://theantitwilightmovement.webs.com/mailbag.htm, 2010) [View larger image.]

[2.7] Beyond its criticism of the rabid mode of fan/antifan engagement, which is most clearly seen in the site's Ragemail sections, the other crucial aspect of ATM's particular antifan identity and Web site is its performed literary critique of the Twilight novels. In the About section of their site, ATM members explain that "our goal is to present an opinion, no matter how unpopular, and inform people that Twilight is not the 'best book ever written'—there are better books out there. We're here to protect the name of literature." They try to make it clear that they do not reject Twilight unconditionally because it is badly written, though they do quite plainly profess to not personally enjoy the books. What they hate, they claim, is the popular opinion of Twilight's literary quality. So they have taken on this literary critique as a sort of social duty and as an affected performance of scholarship that they hope will prove themselves more rational and tolerant, more educated and high class, than the emotional, uncritical rabids they condemn elsewhere on their site.

[2.8] Under a heading marked Our Cause, ATM carefully explains that "the book Twilight by Stephenie Meyer has become overwhelmingly popular among the general population, teenagers especially," before offering its own assessment of the books' literary value, or supposed lack thereof. ATM justifies its claim of the Twilight saga's "poor writing" with descriptions of the novels' "shameless purple prose" and the author's "amateur style" and "elementary sentences." It cites specific paragraphs and page numbers to support allegations of Meyer's excessive modifiers and overreliance on a thesaurus. It even quotes popular yet critically acclaimed author Stephen King and one admin's own English teacher to reinforce its opinions and critique of the novels. The literary critique is not concerned with dismissing Twilight entirely or with denying its potential for providing entertainment and enjoyment to its readers. Instead, it is meant to get Twilight "recognized for what it is": a "guilty pleasure," not as the "best books ever written," which is the assessment often made of them by their uncritically rabid fans.

3. The cultural dismissal of female fans and Twilight

[3.1] ATM is not alone in its characterization of emotional and excessive rabid young female fans and its rejection of the idea that Twilight's value consists of anything more than mere entertainment. The wildly successful Twilight films, which have so far earned more than $1.8 billion worldwide (The Numbers 2010), were adapted from the series of extremely popular novels; Meyer's fantasy romance quartet has sold more than 100 million copies worldwide (Sellers 2010). But financial success has not guaranteed positive reviews, nor has it neutralized disciplining descriptions of its female fans or validated their enjoyment of the franchise (Click 2009; Click and Aubrey 2010). Of the last-released Twilight film, Eclipse (2010), Roger Ebert (2010) writes that "the movies are chaste eroticism to fuel adolescent dreams," and Claudia Puig of USA Today (2010) remarks that "the huge contingent of girls—and women with girlish fantasies—who like the first two movies will doubtless enjoy Eclipse. But this third go-round won't make Twihard converts of the rest of us."

Figure 4. Image of the hundreds of fans who camped out for the premier of Eclipse in the Nokia Plaza in Los Angeles. (http://www.cbc.ca/arts/film/story/2010/06/23/twilight-eclipse-camp-premiere.html, 2010) [View larger image.]

[3.2] The Los Angeles Times (Spines 2010) even published an article around the time of Eclipse's release, addressing what it saw to be the worrying problem of Twilight fans' unhealthy "addiction," when hundreds of fans waited days outside for the LA premier and screamed crazily for the film's young stars. Working from the popularized images of fanatic women, both irrational moms and emotional teenage girls, that surround Twilight, the article depicts these female fans as dangerously out of touch with reality and mentally sick in their fandom: their marriages are falling apart and their children are forgotten as their Twilight obsession takes over their "real" lives. One of the article's quoted self-confessed fans admits that Twilight is "like a drug. I have to read it or I break down crying. It's awful. I don't want to tell anyone about it. But I fear it's unhealthy." Another woman confesses that "'Twilight' was always on my mind, to the point where I couldn't function" (Spines 2010).

[3.3] Of course, such depictions of fans, especially female fans, as mentally unstable, deviant, and somehow dangerous members of society are nothing new. Such discipliningly trivializing accounts have accompanied not just Twilight, but also Elvis, the Beatles, 'N Sync, and today's Hannah Montana and the Jonas Brothers. There is a long tradition of rendering fandom as pathology and capitalizing on the fanatic potential of the term's origin. Joli Jensen explains that "fandom is seen as excessive, bordering on deranged, behavior" and as such, fans are often depicted as deviant, and therefore dangerous "others" to society (1992, 9). Such representations of fans are, in fact, more a reflection of the authoring group's anxieties and values than they are a necessarily accurate portrayal of the fans in question. Henry Jenkins notes that this "stereotypical conception of the fan, while not without a limited factual basis, amounts to a projection of anxieties about the violation of dominant cultural hierarchies," elucidating fans in terms of modes of behavior and established tastes and classes (1992, 17).

[3.4] But indeed, as Ann Gray points out, "there has frequently been a gendered element to the pathologication [of the fan]. Behavior perceived as fundamentally irrational, excessively emotional, foolish and passive has made the fan decisively female" (qtd. in Gray 2003). Reactions like these to Twilight fandom, which seek to qualify and police fan engagement, especially female fan engagement, come not only from the dominant culture, but also from within the Twilight community, from both fans and antifans. Indeed, portrayals of female Twilight fans as emotionally unstable and irrational, and therefore threatening in some way, have appeared in both mainstream newspapers like Los Angeles Times and on countless anti-Twilight Web sites.

4. The antifan and ATM's antifan positions

[4.1] There is not much difference between fans and antifans; antifans can face many of the same cultural depictions of and assumptions about their engagement with a text and their place in society. Scholarship has started to emerge on the position of the antifan. Jonathan Gray (2003, 2005), for instance, has shown that antifans are often just as active as fans and share many similarities in terms of identity and behavior. Gray explains that "hate or dislike of a text can be just as powerful as can a strong and admiring, affective relationship with a text, and [antifans] can produce just as much activity, identification, meaning, and 'effects' or serve just as powerfully to unite and sustain a community or subculture" (2005, 841).

[4.2] Gray defines antifans as those who are not necessarily "against fandom per se…but who strongly dislike a given text or genre, considering it inane, stupid, morally bankrupt or aesthetic drivel" (2003, 70). Many antifans, including the members of ATM, hold a position against the Twilight books themselves, considering them poorly written romantic fluff with problematic messages. However, the antifans of ATM stress they are not opposed to fantasy, vampire, romance, teen, or even massively popular texts and genres, mentioning their own fandom for the teen-focused vampire TV show Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003) and the vampire romance series Vampire Kisses, not to mention the phenomenally popular and fan-inspiring Harry Potter franchise. Instead, they strongly dislike the popular belief that the Twilight books are good literature and that they deserve the fanaticism its rabid fans demonstrate.

[4.3] ATM's position aligns more with the antifan definition that Dan Haggard (2010) has proposed: "They actively hate [the object of their antifandom] and seek to modify other people's perceptions of those texts in a way that more closely resembles their own. They tend to resent [its] success and seek to undermine that success." Although it is true that many of Twilight's antifans hate both it and its success, each of which exacerbates the other, ATM claims to not hate Twilight outright, though it does not personally care for either the books or the movies. Still, ATM members resent the popularity that has made visible the idea, held mostly by rabid fans, that the series is "good literature"; this is an idea they definitely "seek to undermine." They also work to "modify other people's perceptions" of Twilight's literary merit and popularity to "more closely resemble" their own belief that Twilight is worthy of being nothing more than a guilty pleasure and vapid entertainment.

[4.4] Beyond this hatred of the text itself, and of the text's popularity by extension, general Twilight antifans are also defined by their hatred of the franchise's fans. The closest theoretical explanation or definition of this type of antifan engagement and identification is that of the sports antifans Vivi Theodoropoulou has examined. In describing the phenomenon of competition and identity performance surrounding these antifans, Theodoropoulou explains that "a fan becomes an antifan of the object that 'threatens' his/her own, and of that object's fans" (2007, 317). These sports antifans hate the fans of the team that opposes, is in competition with, or somehow threatens, their own. ATM can see Twilight as threatening because of its popularity and therefore its signification as low-class and mainstream, and also because of its supposed lack of literary quality, not to mention the intensity and propensity for excess of many of its female fans, who become threatening and objectionable in their own right. However, ATM did not begin as a group of fans of some specific object threatened by Twilight, like Theodoropoulou's sport's antifans; nor does the threat of Twilight and its rabid fans extend out of this initial fan position. Instead, it stems more from the accepted values of the dominant cultural hierarchy. In many ways, ATM is opposed to the rabid fans (and antifans) of Twilight and subsequently hates Twilight by extension—more so than the other way around.

[4.5] General Twilight antifans reject Twilight fans either as extensions of the despised text, symbols of the popularity which they believe the "bad" series doesn't deserve, or as enactors of a hated mode of fan/antifan engagement, in which any hate of the text in question is incidental to the dislike of those fans' behavior. ATM combines both of these positions in its online identity and Web site, though the latter is much more important to ATM. Not only does ATM reject the popularity of Twilight, but it also opposes many of the franchise's fans, not for simply liking Twilight, but for rabidly liking it. This ties back to Haggard's definition, in which ATM hates the fans who rabidly like Twilight because it believes the "elementary" book to be undeserving of such devoted fans and therefore sees the rabid Twilighter as inappropriate. However, this aspect represents only a small part of ATM's anti-Twilight identity.

[4.6] Mainly, ATM rejects rabid Twilight fans and antifans because they are acting rabidly in general, not because of the text they are connected with. For ATM, the emotion and excess of rabid behavior is much worse than Twilight itself, and even much worse than some fan being too invested in the simple books or movies that ATM thinks are more appropriate as a guilty pleasure than as an obsession. Still, ATM does see some sort of correlation, or at least some unlucky connection, between rabid fans and the text of Twilight, and so Twilight is frequently included in ATM's main critique of generally rabid modes of engagement, both fan and antifan.

5. The cultural hierarchy and ATM's internal antifan definitions

[5.1] Joli Jensen explains that in the dominant cultural hierarchy, "the division between worthy and unworthy is based in an assumed dichotomy between reason and emotion…[and] describes a presumed difference between the educated and uneducated, as well as between the upper and lower classes" (1992, 21). ATM uses these same assumptions when it characterizes and defines rabid fans and antifans as excessive, emotional, irrational, overly invested, out of control, and often young and female, all which make them completely dismissible Others according to the cultural hierarchy. By thus subjugatingly constructing bad rabid Twilight fan identities, ATM positions itself as a group of good antifans who reject undesirably excessive modes of fandom and who reinforce the dominant tastes and preserve the dominant cultural hierarchy; this privileges their position and protects them from similar critiques (Strong 2009, 5).

[5.2] ATM's proposed hierarchy of good and bad fans functions rather like Brunching's pyramid of geekdom, in which legitimate published science fiction authors are ranked higher than those illegitimate fans who post (erotic Star Trek) fan fiction online. Rather than differentiating among themselves according to traditional fan distinctions of authenticity, these antifans focus instead on good and bad performances of fandom and reserve their harshest online responses for the bad rabid behavior (Jancovich 2002, 307–8).

[5.3] Interestingly, though ATM hates rabid fans and antifans much more than they would ever hate a mere Twilight fan, it does see the Twilight books, as well as the movies to some degree, as somehow encouraging, or at least engendering, this type of rabid behavior because of its large base of young female fans and because it is a popular, mainstream, and somewhat low-status text. Notions of popularity and class end up getting incorporated into ATM's objections against these rabids and become extremely important as it moves from denouncing bad fan/antifan behavior to performing its own literary criticism, which functions as the symbol of ATM's own rational and educated high-class superiority.

6. The danger of Twilight's popularity and excessive fans

[6.1] Unfortunately for the ATM collective, the mere criticism of rabid Twilight fans and antifans does not insulate them from associations with the popular Twilight or from the feared excess of fans; nor does their affected literary critique. As Joli Jensen explains, according to the cultural hierarchy, "it is normal and therefore safe to be attached to elite, prestige-conferring objects…but it can be abnormal, and therefore dangerous to be attached to popular mass-mediated objects" like Twilight, with their implication of fandom and therefore of excess (2002, 20). And because fans and antifans are similar in terms of their behavior and modes of engagement (Gray 2003, 2005), antifans like those who comprise ATM can also be associated with the popular object of fandom and with connotations of excess because they devote the same amount of time and energy to being antifans as fans do to being fans. This is a bit of a conundrum that jeopardizes ATM's inherent assertion that its own antifandom is acceptable and nonexcessive. ATM is aware of the fact that although it is rejecting Twilight's rabidly devoted fans and antifans and carrying out a scholarly literary critique that is meant to elevate it above the popular and the mainstream, the fact that it has created an entire Web site and has closely analyzed the Twilight books threatens it with associations of devoted fans and of the rabid-behavior-inspiring Twilight franchise.

[6.2] Therefore, beyond affecting rational academic elitism to counteract the potential pollution of Twilight's popularity, ATM also tries hard to convince visitors to its site that it is not as interested or invested as it would appear that these creators of an anti-Twilight Web site are—that ATM is reasonable and in no way excessive in its antifandom and its connection to Twilight. Responding to the concocted rabid fan question of "Why do you put 90% of your energy into something you hate?" on the FAQ page, ATM writes, "Ahahaha, 90% of my what? You obviously don't understand how fast (and easy) it is to make a website. We barely put any 'energy' into this."

[6.3] It is unclear whether the list of questions from which this one comes was actually submitted by rabid fans for ATM to answer. They are more likely critiques that ATM anticipated hearing from rabid Twilight fans and from the people who would consider ATM to be similarly excessive, so ATM added them to the FAQ to preemptively address them. With this question of energy, ATM addresses, and denies, the same accusation of overinvestment that it similarly uses in its argument against Twilight's rabid fans and antifans. This allows ATM to attest to its own safe, rather than rabid, investment: ATM's answer confirms its safely disinterested involvement.

7. The fear and characterization of excess in rabid fans

[7.1] Because this notion of excess is so threatening, and therefore rejected by society, ATM members work hard to prove that they themselves do not possess it. Similarly, what is most threatening about these rabid fans/antifans, and therefore what comprises ATM's core characterization of them, is their perceived propensity for excess. Although ATM does disapprove of such emotional and excessive behavior as it relates specifically to Twilight, what it really hates is the lack of logic, reason, and common sense that this archetype of rabid fan/antifan embodies, regardless of the text in question. As Jensen explains, being a fan, unlike a culturally acceptable aficionado or academic expert, "involves an ascription of excess and emotional display" that is much less desirable than masculine, educated, or upper-class displays of reason and control (2002, 20). Working from such established cultural distinctions, ATM makes rabid Twilight fans and antifans the ultimate Other to its own affectations of rational literary criticism and sensible observation by defining them in ways that align with traditional depictions of fan pathology and deviancy and that show them to be undesirably excessive.

Figure 5. Screen capture of the warning message that appears upon entry to the Anti-Twilight Movement Web site, showing themselves to be better than intolerant and hostile rabids. (http://theantitwilightmovement.webs.com/, 2008) [View larger image.]

[7.2] One of ATM's main arguments against, and characterizations of, rabid Twilighters states that because they are so excessive in their fandom, so emotional and immature, they cannot so much as hear of a person not liking Twilight without defensively lashing out. One of ATM's many pieces of Ragemail proves this characterization of rabids as emotionally intolerant: "You're stupid for making an anti-Twilight site…you, you stupid fuck tard, are gay and stupid and a loser and all the things you think Twilight are. Get a life. Go die." ATM chose this piece of Ragemail to show rabid Twilight fans at their worst, as incapable of accepting the mere existence of an anti-Twilight Web site or responding to such people with anything other than hurtful personal insults, which the Ragemail shows often resemble the petty and unsophisticated invectives often attributed to teenage girls. In sarcastically and dismissively commenting on these Ragemail messages, ATM cites the mangling of the mechanics of the English language and presents what it shows to be uncalled-for personal attacks and harsh name-calling. This enables ATM to reject these femininely gendered rabid fans for their lack of emotional control and their presumed lack of education, as well as for their youth and their hostile intolerance.

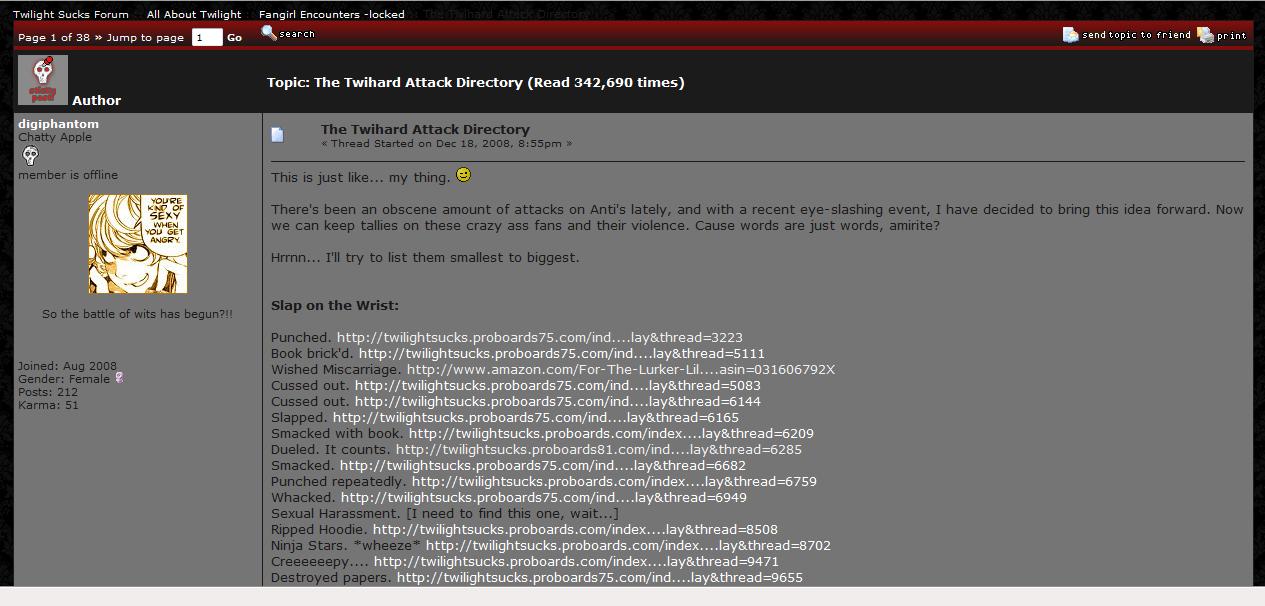

[7.3] Another such characterization of excessive rabid Twilight fans shows them to be so defensive and emotionally hostile that they not only harshly insult anti-Twilighters, but they also resort to actual violence. The Twihard Attack Directory (2008) discussion forum on the Twilight Sucks Web site allows anti-Twilighters to post accounts of being attacked by rabid Twilight fans. In most of the postings, the antifans claim they did nothing to incur the retaliatory action of the rabid Twilighters other than express their simple dislike of the books or movies. The listed assaults include verbal insults, a broken ankle, a cigarette burn, an attempted throat slitting, and a "wished miscarriage," among others.

Figure 6. Screenshot of the Twihard Attack Directory posting in the Twilight Sucks forum showing some of the cited rabid attacks. (http://twilightsucks.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=fangirls&action=display&thread=5175, 2008) [View larger image.]

[7.4] Though these Twihard attacks are completely unverifiable and, as Dan Haggard (2010) points out, have never been reported by any reputable news organizations, such depictions of excess fit perfectly within ATM's construction of rabid Twilight fans as a deviant and dangerous counterpoint to its own affected identity of reason and control. As Jensen explains, "Once fans are characterized as deviant, they can be treated as disreputable, even dangerous 'others'" (1992, 9). And while young female fans of the popular Twilight might be seen as somehow generally unsavory, antifans like those who comprise ATM can apparently act on behalf of society at large by justifiably condemning these dangerous fans when they have been shown to commit actual violence, especially unprovoked intolerant violence, in the name of their fandom.

8. Excess continued: Rabid antifans

[8.1] Even more threatening to ATM than the rabid fans that it so thoroughly rejects are the excessively rabid anti-Twilighters who are said to attack Twilight fans with as little rationality and as much violent emotionality as is attributed to the rabid fans. For although ATM despises the rabid fans of Twilight, the rabid Twilight antifans are a more direct threat to its own position of Twilight antifandom. This group of excessively rabid and violent Twilight antifans is epitomized in the near-militant group called Anonymous, which uses harsh language and violence to ruin the experience of Twilight for its fans. The group posts instructions online (under the names Project Golden Eye and Operation: No Moon), ordering anti-Twilighters to spoil Twilight film premiers with rude and obscene behavior, to post gay porn and gore-filled fan fiction to Twilight fan sites, and to harshly insult Twilight fans at every possible opportunity (accessed December 18, 2009; site now discontinued).

[8.2] Anonymous's aim is to attack, violently, anyone who expresses even the slightest interest in Twilight, no matter his or her reasoning or degree of fandom. For ATM, Anonymous and other such rabid antifans are just as intolerant and irrational as the rabid fans seen on the Ragemail and the Twihard Attack Directory. Thus, ATM gives these rabid antifans their own Ragemail page where their excessive and violently emotional behavior is denounced for its repulsiveness and because, as ATM writes, "you give us a bad name."

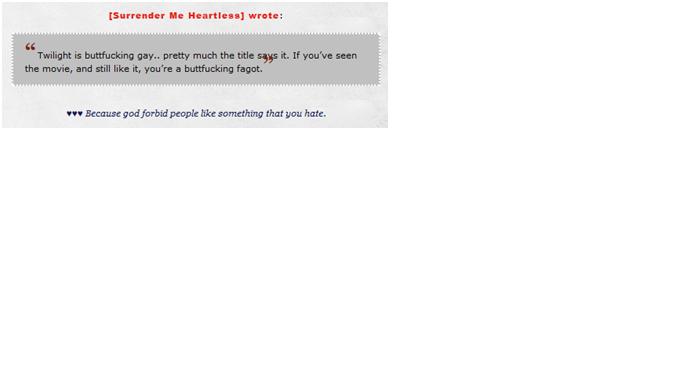

[8.3] Interestingly, this group of violent rabid anti-Twilighters seems to have intentionally aligned itself with the violence and irrational excess that ATM so thoroughly condemns in others and fears to be associated with itself. The majority of these rabid antifans are male, and their displays of violence and harsh and sexually degrading language are their way of unequivocally rejecting the sentimental femininity attributed to most Twilight fans and to the series as a whole. Though Anonymous uses the same type of ruthless, insulting language that rabid fans were shown to use in ATM's Ragemail, the two groups code their words differently. Where the Twilight fans use femininely gendered terms like bitch and slut to attack female anti-Twilighters, Anonymous uses homosexual insults and intensely harsh curse words to convey the masculine anger and violence that is part of its antifan identity and performance.

[8.4] For instance, Anonymous justifies its plan to ruin the premiere of the second Twilight film for its fans by explaining that "we could not possibly let such a piece of shit come to pass without any consequences, as the fans of the fagboat are worse than the book/movie itself." Interestingly, the homophobic term gay did appear in the more feminine rabid Twihard Ragemail cited above (see ¶7.2), though it seems to have been used merely as one piece in a string of personal insults, unlike this direct attack by rabid antifans on the perceived gender of the series and its fans. Just as ATM hates rabid Twilight fans/antifans and the popular belief in Twilight's literary worth more than it hates Twilight itself, Anonymous's anger seems to be mainly directed at the fans of the popular series ("the fans are worse…"). Still, Anonymous makes it clear that it hates Twilight almost as much as it hates its fans, and it expresses that hate much differently than ATM. Its use of terms like "fagboat" and "piece of shit" to describe the franchise and threatening violent "consequences" for its existence is almost the polar opposite of ATM's attempt at reasoned literary assessment of the books and its refutation of only excessive fans, not every person connected to Twilight.

Figure 7. Screen capture of one quoted rabid anti-Twilighter message from the Anti-Twilight Movement's antifan Ragemail section of their Web site. (http://theantitwilightmovement.webs.com/antimailbag.htm, 2010) [View larger image.]

[8.5] Such wholesale intolerance can be further seen in a piece of ATM's rabid anti-Twilighter Ragemail: "Twilight is buttfucking gay…If you've seen the movie and still like it, you're a buttfucking faggot." Again, this message contains the same homophobic language and harsh hostility that mark the rabid antifans' masculine expression as well as the intolerance of differing opinion that also characterizes ATM's depiction of rabid Twilighters. Where the rabid fans couldn't accept those who disliked Twilight, here the rabid antifans can't allow anyone to have so much as seen the movies and liked them, even if they do not act rabidly about it. They espouse the total dismissal of Twilight fans, and indeed of the series itself, which ATM is careful never to do, for fear of being accused of irrationality and excess. Therefore, ATM concedes that people will, and may, like the books and movies, even if ATM members themselves do not. On the other hand, rabid anti-Twilighters apparently cannot accept or allow the text on any level, and they attack Twilight outright with emotional insults rather than objective reasoning.

[8.6] ATM not only cites the angry messages of rabid anti-Twilighters, but also condemns all such violent and intolerant antifans and specifically denounces Anonymous on their Wall of Shame. Here, ATM lists all the rabid anti-Twilight sites that it claims are "appalling and malicious" in that "they're just as violently crazy about Twilight as rabid Twitards, only instead of violently loving it, they violently hate it and anyone who reads it." Discussing internal fan identities, Henry Jenkins explains that "even within the fan community," categories and labels of "other" and "inappropriate" engagement are applied as a "way of policing the ranks and justifying one's own pleasures as less 'perverse' than those of the others" (1992, 19). Haggard (2010), too, has suggested that the entire phenomenon of the Twilight antifan exists as a "reaction designed to signify to others within a group, a person's rejection of an opposing group."

[8.7] True as this is for the group of Twilight antifans as a whole, it also applies to ATM as a specific faction within Twilight antifandom: ATM needs to differentiate itself from the damning characterizations of other rabids, especially rabid antifans. Through such internal fan (and antifan) definitions and negations and the establishment of an antifan hierarchy, by citing the emotionally excessive behavior of rabid Twilight fans and antifans and by attributing the label of rabid in the first place, ATM seeks to render its own Twilight antifandom acceptable and appropriate in comparison. Through this construction of a safe "us" versus a dangerous "them," ATM is able to reassure itself and any outsiders that it is "not as abnormal" as those other hostile and irrational fans and antifans and is, in fact, much better (Jensen 1992, 24).

9. Good antifans: ATM's self-characterization as superiorly rational and tolerant

[9.1] In contrast to the characterizations of excessive and violent rabids, of the bad fans and antifans, ATM attempts to prove itself as good antifans by displaying the reasoned control and civil discussion that mark the culturally accepted and superior classification of high-class connoisseur, aficionado, or scholar. Joli Jensen reasons that "defining disorderly and emotional fan display as excessive allows the celebration of all that is orderly and unemotional," and therefore ATM constructs itself as superiorly "orderly and unemotional" in relation to their characterizations of rabid excess. Because "self-control is a key aspect of appropriate display" in this definition of a high-class scholar and a good antifan/fan, ATM defines its own attachment to Twilight as comprising "rational evaluation [that is] displayed in more measured ways" than that of the emotional and narrow-minded Twitards that it denounces on its Web site (Jensen 1992, 20, 24).

[9.2] In performing this apparently superior rationality, ATM not only logically and thoroughly explains its position and arguments against Twilight as literature and against its rabid fans/antifans, but it also strives to never display the same emotional hostility or irrational intolerance that it shows the rabids to do. ATM writes on its site, "You [rabid Twilight fans] don't respect our opinion. That's why you won't let us criticize your favorite book without sending us hate mail, insulting us, and threatening us." Here ATM purports to be carrying out a valuable literary critique of Twilight, a reasoned and civil (and presumably somewhat objective) discussion of the book, rather than an emotional attack on the fans themselves. Beyond stressing ATM's own scholarly position, this message further reminds visitors that rabid fans and antifans lack not only the educated and mature (and masculine) capacity for such rational evaluation of Twilight, but also the same common courtesy of tolerant acceptance. ATM and its affiliated sites try hard to be the opposite of this, to tolerate the existence and position of Twilight fans.

[9.3] As proof of their proclaimed acceptance of good Twilight fans, of the ones who are tolerant and level-headed like themselves, the antifans that comprise TRS make an effort to differentiate between Twihards and Twitards. Twihards are the devoted yet permissible "die-hard Twilight fans," while Twitards, who are similarly obsessed with Twilight, are unacceptable because they take their fandom to excessive and rabid levels. It is the Twitards, not all Twilight fans, who are seen as threatening and immaturely "incapable of respecting others' opinions." TRS clarifies that "not all Twihards are Twitards. People can like the books without being a Twitard: What separates Twitards from Twihards is their behavior." For these antifans, avid Twilight fandom is not the problem. Instead, it is the loss of control and rational thought that underlies these rabid fans' perceived intolerance and uncritical love of Twilight that upsets them. TRS explains that "mature Twilight fans…understand that not everybody likes the books." This depiction of the good Twilighters ("mature") not only allows TRS to define good fandom in a manner similar to its own tolerantly affected mode of antifandom, but also further denounces the youth and immaturity that marks its construction of emotional and excessive rabid Twilight fans.

[9.4] Such distinctions between good and bad fans can be seen on ATM's site as well: the Welcome message explains that "the [Twilight] books just don't appeal to us. But if they appeal to you, that's fine. We understand that it's a book, and there's nothing wrong with liking it. However, we also understand the difference between the fans that enjoy the books and the rabid fans that take them much too seriously." Here, upon first entering their site, is ATM's tolerant acceptance of Twilight fans in general, as well as of the basic enjoyment of the books, an affectation that inherently rejects the rabids whom, it claims, in "taking Twilight much too seriously," lose this rational ability to allow disparate opinions and viewpoints. And, as it showed in the Twihard Attack Directory and Ragemail, when rabids take Twilight so seriously that they literally attack anyone who remotely dislikes the books, it is dangerous for everyone.

[9.5] ATM members' position seems to propose that, in contrast to those threatening rabid fans, it is much better and much safer to be a fan or antifan like themselves, who accepts that some people like the series (even if they themselves do not) and who won't attack them for it. In other words, they are better for being rational and unemotional enough to not take their Twilight antifandom too seriously, for embodying the cultural hierarchy's privileged attributes of (masculine) reason and educated logic.

10. Another consequence of excess: Fans depicted as detached from the "real world"

[10.1] ATM's dismissal of fans that take not only Twilight, but anything, too seriously rejects fans for the excess and emotionality that connotes them to be inferiorly uneducated, lower class, and probably young (and female), but it also rejects them for their inability to properly assess the "real world," one of the other traditional indictments made against fans (Jensen 1992; Jenkins 1992). Joli Jensen explains that "there is a thin line between 'normal' and excessive fandom. This line is crossed if and when the distinctions between reality and fantasy break down. These are the two realms that must remain separated, if the fan is to remain safe and normal" (1992, 18).

[10.2] ATM characterizes rabid fans and antifans in such a way that they are made to cross the line that divides normal from excessive. Having been shown to cross that important boundary, the rabids then face consequences for their irrationality—consequences that manifest as "cautionary tales of fans who go 'over the edge' into fanaticism, and thus pathology" (Jensen 1992, 18). Such disciplining "cautionary tales" exist in the Los Angeles Times article's depiction of "sick" female fans (Spines 2010), as well as in ATM's own unflattering Ragemail excerpts and TRS's Twihard Attack Directory (2008).

[10.3] However, ATM seems to understand that as long as the fan (or antifan) shows "good common sense" and remains "rational" and "in control," he or she will be spared the condemnatory and pathology-citing discourses of the dominant hierarchy. Thus, ATM matches every one of their site's descriptions of rabid excess with a measured and logical response, hoping to show its own good common sense and prove that it is still in control, that there is no need to be similarly chastised with the label of "rabid" or "fanatic." In embodying and promoting this good commonsense behavior as appropriate in comparison to fanatic irrationality, ATM is not only protecting itself, but also perpetuating that cultural notion about fans' propensity for unreality, and continuing to hold up similar consequences for such pathological behavior.

11. The academic, the elite, and ATM's affected literary criticism

[11.1] ATM strives to show itself not only as possessing that all-important good common sense, but also as so unemotional and high class that it is capable of carrying out sustained literary criticism, thus providing a logical and rational explanation of Twilight. As previously mentioned, ATM's position is not wholeheartedly anti-Twilight, but instead is interested in qualifying the hyperbolic statements made by uncritical rabid fans about the books' unmatchable value, an example of which is the unequivocated rabid assertion that "the Twilight saga, They ARE the best books." TRS explains that "there's nothing wrong with liking a less-than-great…book. We've all got our favorite guilty pleasure or two. But we really hope you see, and enjoy, Twilight for what it is." ATM similarly reaffirms their shouldered responsibility toward literary value and toward debunking the popular notion that Twilight is great literature: "Our goal is to…inform people that Twilight is not the 'best book ever written'—there are better books out there. We're here to protect the name of literature and show you a viewpoint that may oppose your own." With these grandiose claims of protecting the very name of literature, which they proudly boast to have been doing since 2008, ATM differs somewhat from most other Twilight fans and antifans: it claims to be carrying out culturally significant work, rather than simply expressing a dislike of something or creating a hate site.

Figure 8. Screen capture of two buttons that ATM sells on their site. The first proclaims their affected interest in the sanctity of literature, while the second plays on fan shipping between Bella's two love interests, vampire Edward and werewolf Jacob, to privilege literary quality over fan emotionality. (http://theantitwilightmovement.webs.com/merch.htm, 2010) [View larger image.]

[11.2] This performance of "protecting the name of literature" and of critiquing Twilight ensures that antifans like ATM appear educated, high class, and rational enough to evaluate literature, which presumably aligns them with elite academia rather than with popular fandom. The issue of popularity is an important one to consider in ATM's critique, and qualified rejection, of Twilight. Though its popularity is by no means ATM's main reason for dismissing Twilight, it doesn't help. Popularity carries with it connotations of the mainstream and the low class, as well as the potential threat of fan deviancy (Jensen 1992); and at times, ATM pushes its position of rejecting rabid Twilight fans for being attached to a popular text to the forefront of its site and its arguments.

[11.3] While hoping to avoid any negative stigmas of Twilight's popularity, ATM also uses its literary criticism of the books to align itself with the academic and the elite, thereby privileging its own antifandom, as well as safeguarding itself against the claims and censures of excess and emotionality that traditionally meet fans. Henry Jenkins explains that "from the perspective of dominant taste, fans appear to be frighteningly out of control, undisciplined and unrepentant, rogue readers [who reject] the aesthetic distance" often called for by academics and elites (1992, 18). ATM is all too aware of this perception, and of the disciplining accounts of fans that are circulated by the dominant culture as well as by itself. To avoid such condemning depictions, ATM strives for the aesthetic distance that Jenkins mentions. Such distance relates to the unemotional, the rational, and the masculine, which Jensen previously explained were located at the top of the cultural hierarchy and are attributes traditionally denied to fans. In offering this performed academic critique, ATM is hoping not only to position itself toward the top of that hierarchy, safe from the polluting influences of popular texts and emotional fandom, but also to show itself to be made up of valuable and elite scholarly people.

[11.4] But of course, the members of ATM are not actual scholars, nor are they, following Matt Hills's categorizations, scholar-fans or fan-scholars (2007, 40; 2002, 15–17). Instead, they can only take on the affectation of academia and appropriate academic discourses in the hopes of elevating their antifandom above the emotionality often attributed to the fans and the popularity of Twilight. Hills explains academia as not something real and concrete, but as an imagined "system of value" in which the "'good subject' of the 'duly trained and informed' academic is a resolutely rational subject, devoted to argumentation and persuasion," often set up in diametric opposition to constructed characterizations of the fan (2002, 3). Regardless of the illusory quality of such values, ATM members, though not actual academics themselves, still uphold and attempt to embody them and to behave as good academics in order to elevate their antifandom to the culturally privileged realm of academia.

[11.5] Like Hills's scholar-fans, ATM also maintains this "imagined subjectivity of [the] 'good' rationality" "of academia" to keep their antifan engagement respectable and legitimate in the potential eyes of other scholars (Hills 2002, 4, 11). Where real scholars' academic legitimacy would be potentially threatened by their emotion-based fan associations, ATM sees itself as similarly threatened, even though they are not made up of actual scholars and are denouncing Twilight, not fanatically loving it. They perform the "imagined subjectivity of 'good' rationality" as well as Jenkins's "aesthetic distance" not to maintain the respectability of academia, but in the hopes of obtaining that respectability for their antifandom.

[11.6] Still, ATM's having constructed an entire antifan identity that co-opts the cultural weight often attributed to literature and its criticism for its affected scholarly critique of a massively popular book is potentially complicating. Originally, neither Twilight nor its fans (or antifans) would have fallen within the scope of literary studies. The popular young adult books are not considered art or good literature by anyone but its devoted fans, and the antifans critiquing them are not actual scholars. It is this last aspect that truly threatens ATM with the cultural admonishments that it had hoped its literary critique would protect it from. Henry Jenkins explains that fans are threatening to dominant society because they disrupt established notions of taste and quality by "treating popular texts as if they merited the same degree of attention and appreciation as canonical texts" (1992, 17). Unfortunately, the "reading practices (close scrutiny, elaborate exegesis, repeated and prolonged reading, etc.) [that are deemed] acceptable in confronting a work of 'serious merit' seem perversely misapplied to the more 'disposable' texts of mass culture" (1992, 17).

[11.7] ATM's enactment of such a critique of Twilight, as well as its belief that it can be critiqued at all, even though it pronounces Twilight as devoid of literary merit, inherently asserts that the extremely popular series of fantasy young adult novels deserves the same cultural attention as canonical and so-called great works of literature. Although ATM's literary critique was meant to legitimize ATM's mode of antifandom and distance it from connotations of emotional excess, it also potentially aligns ATM with the cultural disapproval that has traditionally met fans as "rogue readers" who give the weight often reserved for elite works to mainstream objects (Jenkins 1992, 18, 24).

12. The rejection of the feminine and female fandoms

[12.1] It is interesting to point out that ATM uses the jargon and discourses often used by arbiters of dominant taste to police and denigrate not merely fan behavior, but also specifically female behavior and values. However, it does not make the claim that all women necessarily act like the deranged female fans in Spines's Los Angeles Times article (2010) or like the girls characterized in ATM's own Ragemail; nor does it find all women and female cultural artifacts inherently dismissible. In her study of the Cracked forums, Catherine Strong found that the female Twilight antifans there essentially believe that "teenage girls' culture is 'bad'" and that Twilight, because aimed at this demographic, is "basically as close to worthless as it can" be (2009, 9). These antifans claim that Twilight "sucks because it was written for teenage girls" and refer to those teenage girls with classically belittling descriptions of screaming and squealing (2009, 9).

[12.2] This is a far cry from the sophisticated judgments and logical assertions that ATM hopes to make about Twilight and its fans, as well as about its own antifandom. ATM never comes right out and says that Twilight is worthless (tempted though it seems to be). ATM has a long and detailed literary critique of the book that condemns it as badly written and thematically problematic, but it does not blame what it sees as its lack of literary quality on the supposition that it was "written for teenage girls." ATM does use some of the same descriptions of generally female rabid fans as screaming and as having bad taste in their uncritical love of the popular, but it uses these descriptions to negatively characterize rabid modes of fan engagement, not to condemn all girls or all fans in general. Though ATM does use some of the same femininely gendered attributes in a criticizing manner and dismisses such behavior because of where it falls on the cultural hierarchy, it tries hard to never comprehensively reject texts with predominantly female fandoms, nor all female fans in general (even if it does believe them to be more prone to such rabidly excessive behavior).

[12.3] Despite this effort toward qualified rejection, ATM perpetuates the placing of the feminine at the bottom of the dominant cultural hierarchy; and it still participates in the cultural assumption that fans, especially female fans, are threatening because they flout and undermine established societal ideals and moral standards. This is comparable to Beatlemania, where what was labeled inappropriate and fanatic in these teenage girls—the loss of control, the screaming, the fainting, the mobs—was defined thus because it challenged the then-prevailing ethos of teenage purity (Ehrenreich, Hess, and Jacobs 1992, 181). Arguably, analogous threats to the dominant culture's asserted moral and social values of female behavior might underlie most of the major manias of female fandom: the mobs of girls screaming for Elvis's hips, the teenagers crying over 'N Sync and the Backstreet Boys, and even the recent explosion of "BieberFever" for the young singer Justin Bieber that has infected predominantly preteen girls.

[12.4] Furthermore, the label of "mania" and the largely disciplining discourses that surround these principally female explosions of fan expression reveal a potential societal fear of the articulation of a collective female desire. Indeed, in descriptions of the pathology and threat of fandom, "the eroticized fan is almost always [depicted as] female" rather than male (Jenkins 1992, 15). Think of the stereotypical image of the woman obsessively swooning over a male celebrity versus the nerdy man who frequents comic book conventions.

[12.5] Twilight poses a threat to society because of its potential for the expression of female desire, and thus it faces similarly policing descriptions of its fans as susceptible to mania, emotional, and irrational. This romance franchise contains archetypically seductive vampire characters and attractive young male stars, while the "femininely" melodramatic narratives promote the "express[ion] of 'intense' emotional states" (Williamson 2005, 64). These aspects have traditionally meant that objects of female fandom, such as soap operas, were dismissed and downplayed by the dominant masculine culture, and the investment and pleasure of its female fans were regarded as unimportant and not valuable. It is these aspects that can make Twilight, and its mass of loyal female fans, seem so threatening to the dominant culture. Not only does Twilight foster intense emotional states and the expression of desire in its female fans, but also its fans are now in a position to really make themselves heard and to loudly articulate their desire for the series and for its male characters and the actors who play them.

[12.6] The teenager and mom-aged female fans of Twilight have at their disposal the information and wealth of images from the Internet to feed their obsessions, as well as a plethora of online communities and discussion forums where they can share and encourage their fandom and desires with like-minded women. This is not a comforting fact to everyone, as can be seen in Spines's Los Angeles Times article (2010). Continuing her accusations of unhealthy female fan addiction, Spines writes that "for some [female Twilight fans], the romance, intrigue and celebrity gossip that's always just a mouse click away is too hard to resist…Instead of watching soap operas all day, they're online following 'Twilight,'…seek[ing] solace in the company of fellow online lonely hearts," undermining both the value of female connections and the authoring potential of the Internet for female fans.

[12.7] In a way, ATM works as a valuable counterexample to this idea of the undesirability of female fan articulation, authorship, and collective online communication. Though it seems to hold some of the same negative views of female fans and indeed uses the dominant culture's terms to dismiss certain feminine fan behavior and therefore elevate themselves, ATM is proof that female fandom (in this case, antifandom) is more than lonely women seeking "fellow lonely hearts" to commiserate with.

[12.8] ATM is evidence that the coming together of female antifans can be smart and productive and valuable in terms of society's own gendered definitions. ATM rejects the same threatening notions of feminine emotionality and irrational excess that the dominant culture does, and it reaffirms the hierarchy that privileges the elite, the academic, the rational, and the masculine over such feminine traits. In addition, in crafting a Web site to publish its antifan identity, which ATM claims was an "easy" task, it attests to its members' own abilities to be active engagers with texts and media, as well as authors in their own right. This is an interesting counterpoint to what Click (2009) points out to be the "persistent cultural notion" that "men and boys are active users of media while girls are passive consumers."

13. Female fans as dangerously passive and vulnerable

[13.1] Though perhaps inherently countering accepted tropes of fan passivity, ATM still attributes that cultural supposition to some of the rabid Twilighters it responds to in its antifandom. It sees rabid fans as "gullible," "conformist," and easily "seduced" by Twilight's massive popularity, as well as vulnerable to any dangerous messages hidden within the text (Jancovich 2002, 312). This fits with the traditional characterizations of fans that have labeled them uncritical "dupes," "blind receptors to corporate propaganda and establishment ideology," and easily seduced by Hollywood celebrities—descriptions that carry gendered connotations of feminine passivity (Gray 2005, 67).

[13.2] ATM utilizes these same assumptions, condemning rabid Twilight fans for their uncritical acceptance of the books and their infatuation with the series' popularity, as well as for their unthinking echoing of claims of its literary merit, which we have seen characterized throughout ATM's Web site. Of course, such depictions privilege ATM's own critical and astute antifandom, and in perpetuating cultural notions of fan passivity, especially in female fans, it works to prove that it poses no such threat to dominant society.

[13.3] This potential threat that uncritical fans pose to society increases when they unite into groups and their individual passivity becomes compounded (Jensen 1992). Picture an out-of-control rock concert crowd, or the brainwashed audience of a cult like the Peoples Temple, or the lines of screaming young female fans waiting for the midnight release of the latest Twilight movie. In this manifestation of fandom, "the frenzied crowd member invokes the image of the vulnerable, irrational victim of mass persuasion" (Gray 2003, 67). ATM also uses this depiction of the vulnerability of groups of fans to reject rabid involvement with Twilight as dangerous and to show itself to be safe in comparison. It positions itself as better than the emotional girls who greedily and unquestioningly consume the popular series, those whose uncritical and rabid engagement leaves them susceptible to mass manipulation.

[13.4] Like many subcultures that have positioned themselves against a construction of an "inauthentic Other," often embodied in the "image of mass culture" and most especially in the consumer of that mass culture (Jancovich 2002, 312), ATM has constructed itself as a superior subculture within Twilight fandom. Additionally, in its construction of these rabid teen girls as passive consumers of mass culture, ATM plays up their disapproval of fans of low-status, mainstream objects to show the vulnerability of a crowd of inundated fans and the dangers potentially inherent in mass-produced entities. In contrast to this, ATM appears as the shrewd consumer of mass culture, capable of discerning any of the text's potentially troubling messages that frenzied fans would passively and unknowingly internalize, and even of warning others about them.

14. ATM's moral objection to Twilight

[14.1] Not only does ATM claim to be capable of identifying Twilight's underlying mass-circulated messages that seduced young rabids have no idea exist, but it also uses these exposed messages to express its moral objection to the book series, citing the problematic ideas that might be instilled in its young female readers. This moral objection is perhaps an extension of ATM's fear of the mob mentality and uncritical susceptibility of Twilight's screaming young female fans (or the traditional belief in such), or simply another way of strengthening its construction of a bad Other fan in relation to its own proposed antifandom. In his examination of Television Without Pity, Jonathan Gray discusses the moral objections antifans can have to different media texts and explains that their desire to post a response to the text based on a moral objection "suggests a desire to warn others and, hence, to spread their reading of the moral text" (2005, 848). One of ATM's readings of Twilight defines the "correct" form of investment with the popular and "poorly written" books, and reveals their participation in the dominant cultural hierarchy's values and perceived threats. For ATM, fans read Twilight incorrectly when they become rabid about it—when they become inappropriately emotional, irrational, and hostile. ATM warns against such behavior.

[14.2] But ATM's main reading of Twilight as a moral text exposes what it sees as the social reality beneath the fantasy romance narrative: the dangerous ideas that threaten the series' passive female fans. It is not my intention to explicitly examine any of Twilight's inner messages, problematic or not, only to discuss the ways in which ATM views and responds to them (for a more detailed examination of the specific potentially problematic themes in Twilight, see Click, Aubrey, and Behm-Morawitz 2010). ATM claims that "Edward and Bella have a disturbingly abusive relationship," explaining that Twilight "is indicative of a pattern in our society to idealize unhealthy and abusive relationships. This book teaches our generation that abusive relationships are okay—no, ROMANTIC, even. Not only is this book a moral threat to our youth, but an assault on literature itself." Henry Jenkins has explained that "materials viewed as undesirable"—here, rabid and uncritical fan investment in the popular Twilight—"are often accused of harmful social effects or negative influences upon their consumers" (1992, 16–17). The series that attracts hordes of young female fans and in some way facilitates their rabidly emotional and uncritical behavior is here labeled as a viable social threat for idealizing, and even encouraging, abusive relationships.

[14.3] The claim that Twilight represents a "moral threat to our youth" is a particularly compelling example of ATM's attempt to protect dominant aesthetic preferences and societal values from the undesirable effects of Twilight and its excessively emotional and irrational female fans, who would be unable to assess the reality beneath the fiction. Whether this underlying social message of sexism and abuse truly exists, or whether it is even one of the real causes of ATM's objection to Twilight, is irrelevant. ATM's performed concern for young and female readers of the Twilight texts, and for society in general, serves to protect them from the feared connotation of rabid gullibility, and its moral objection provides it with a compelling point of opposition that cannot be dismissed as merely emotional hate, or even as simply literary.

15. Conclusion

[15.1] Antifans like those comprising ATM have responded not only to a massively popular book and movie series, but also to an entire culture of fans and antifans. They have participated in and reinforced many of the values of the dominant cultural hierarchy, describing rabids in such low-ranking and often feminine-gendered ways as illogical, emotional, excessive, uneducated, young, and passive. However, ATM's rejection of rabid modes of fandom not only represents a reaffirmation of dominant cultural values, but also an attempt by ATM to construct its own identity by contrasting itself with such Others. ATM represents only one specifically articulated antifan identity; it by no means showcases the full spectrum of fan/antifan response, Twilight related or not. We should continue to explore all the various fans and antifans out there, and investigate the popular as well as the elite, the low class as well as the high, not because we can then neatly explain them or provide clean-cut answers to some of culture's phenomena, but because their voices are valuable and should be included within the big picture.