1. Introduction

[1.1] The concept of fading is centered in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium; every achievement tumbles inevitably to ruin. One such manifestation of this concept is the fading of the Elves, an immortal people in Tolkien's world whose role diminishes as the story transpires from The Silmarillion—the earliest history of Middle-earth—through to The Lord of the Rings (LOTR). The Elves begin as an active people who apply their wisdom and energy to the betterment of their world, but they are immortal, not eternal, and cannot exist in corporeal form under the duresses of our world ad infinitum: They fade.

[1.2] By the end of Tolkien's tales, as described in The Hobbit and LOTR, the fading of the Elves is well underway. Some weary of the world and take ship to a paradisaical land called Aman that is supernaturally detached from our world. Others stay, but their bodies literally fade, persisting in ghostly form as spiritual matter. Either way, and no matter their choice, they can no longer effect change in their—in our—world using capabilities we perceive as magic. LOTR is a narrative about the victory of the humble and small over the powerful and cruel. It is a triumphant, eucatastrophic story. But the fading of the Elves—occurring even as the heroes prevail—overlays the story with a pallor of sadness. As the Elven ships disappear against the westering sun, we are to understand that the world has gained much, but it has lost something, however small and beautiful, as well.

[1.3] Elves, and the fading of the Elves, are an apt metaphor for the rapid rise of Tolkien fan fiction archives at the beginning of the fandom's online history. Tolkien fandom and Tolkien fan fiction have existed for decades, with the first known fan fiction works published in 1960 as part of the fanzine I Palantir. Tolkien himself refers at several points in his published letters to fan works sent to him by fans, including fan fiction. Like many pre-internet fandoms, Tolkien fandom centered on in-person gatherings and hand-produced fanzines. Although online Tolkien fandom existed in the 1990s, by the early 2000s, a confluence of factors resulted in its rapid rise, which included the creation of dozens of fan-built archives.

[1.4] In her book Rogue Archives, Abigail De Kosnik (2016) calls the endeavor undertaken by these fans techno-volunteerism: the labor of mostly nonprofessional volunteers aimed at preserving digital content through online archives. The Tolkien fans who built archives in the first decade of the 2000s fit De Kosnik's definition of the techno-volunteer. Most were self-taught and undertook their labor out of a desire to make accessible fan works that they believed worth preserving. Tolkien fan fiction is still being steadily produced; in May 2023, the Archive of Our Own (AO3) tag "TOLKIEN J. R. R." gained about twenty-two new fan works each day. However, the means of sharing and preserving those works now looks very different than it did in the 2000s. The dozens (if not hundreds) of small archives, each backed by a community of fans, have largely disappeared, quietly and without fanfare, with activity shifting largely to AO3 and a handful of social media sites, such as Tumblr and Discord. This transformation can feel like the inevitable outcome of an evolving fannish internet, much as the fading of the Elves in Tolkien's legendarium is a fated part of their history, but small archives succumbed to a variety of factors, none of them inexorable. The only certainty is the loss of history and community that their demise represents.

2. Becoming an elf

[2.1] I am an elf. I don't mean a capital "E," immortal, sea-longing, leaf-eared Elf from Tolkien's world but an archive elf, to use the term for techno-volunteers coined by Francesca Coppa (quoted in De Kosnik 2016). I am someone who built and runs a fan works archive: the Silmarillion Writers' Guild (SWG). Founded in 2005 on Yahoo! Groups and LiveJournal, the SWG was intended as a writer's workshop to be run on those platforms. Like many communities, however, the idea of an archive for our stories enchanted us, and I agreed to try to build one. Lacking formal technical training, I spent two years learning the skills required. The SWG archive opened in June 2007.

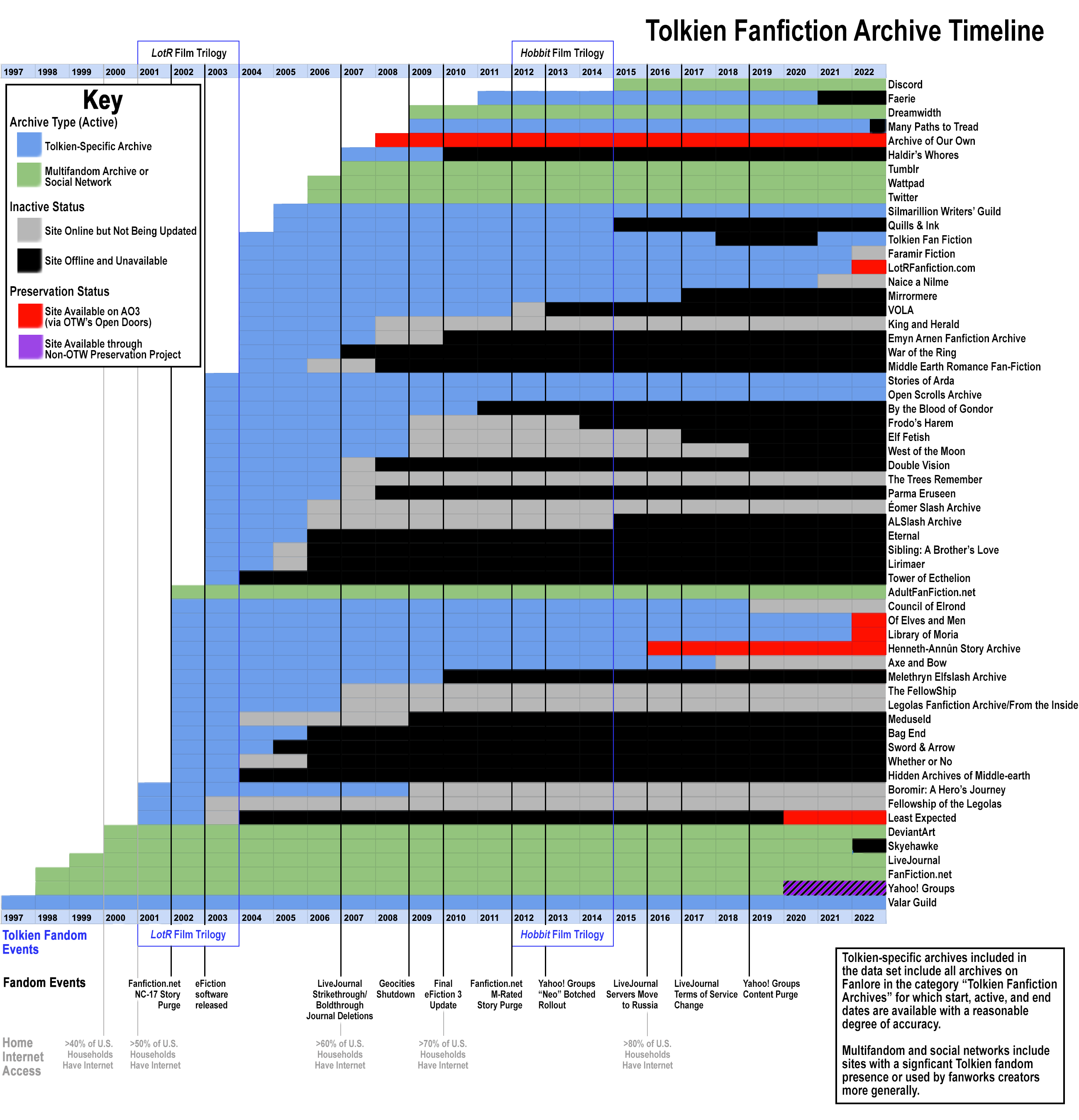

[2.2] In the year 2005, starting an archive was not an unusual choice for someone running a community for Tolkien fan fiction. As De Kosnik (2016) observes, mid-2000s fan fiction groups that were rooted in social networks like LiveJournal and Yahoo! Groups often constructed archives as a more public, permanent record of the community's culture, as preserved in its fan works. My archive timeline (figure 1) shows that this certainly holds true for the Tolkien fandom. Of the forty-seven Tolkien-specific archives included, I was able to document that 64 percent of them sprang from social networks, mostly Yahoo! Groups or forums.

Figure 1. Timeline of start, active, and end dates for Tolkien fan fiction archives (Dawn Walls-Thumma).

[2.3] Figure 1 is a timeline of archives and social networks used by Tolkien fans to share fan fiction. Using the Fanlore category "Lord of the Rings Archives" as my starting point, I have included only English-language archives where I can reliably establish a start and—if relevant—end date and determine in which years the archive was active, defined as at least one fan work posted or updated in that year. In all cases, I have independently confirmed the Fanlore dates to be accurate. The timeline shows during which years each archive was active, as well as when archives went off-line or became available through preservation projects, such as Open Doors. The timeline at the bottom shows key events in both the Tolkien fandom and fandom overall that particularly impacted archive use, as well as the percentage of US households reported via census data to have internet access. My intention was to reveal patterns between historical events and archive activity.

[2.4] One of the more prominent takeaways from figure 1 is the abrupt upsurge in the number of Tolkien-specific archives (shown in light blue) beginning in 2002. It is easy to explain this sudden interest in archive-building in the Tolkien fan community as due to the popular and critically lauded LOTR film trilogy, released 2001–2003. However, as Maria K. Alberto and I (2022) argue elsewhere, there are other historical factors in play that act synergistically with the trilogy's release. First is growing access to home internet and the advent of Web 2.0, which allowed internet users to not only consume static content online but also produce, share, and interact around content.

[2.5] Most of the archives that opened in 2002 were nonautomated, meaning that the archive elves who ran them had to upload stories and code or mark up pages manually. Of the thirteen Tolkien-specific archives that opened in 2002, eleven of them (85%) were initially nonautomated. The remaining two were automated archives—authors could upload their own stories—and relied on custom code written by their archive elves. Both nonautomated and custom-coded automated archives required technical skills and a significant outlay of time and effort to maintain. In 2003, a fourth factor contributed to the ongoing rise in the number of Tolkien-specific archives: Rebecca Smallwood released the open-source eFiction automated archive script, sharply cutting the amount of time and skill needed to build and maintain an archive. The first Tolkien-specific eFiction-powered archives began to open in 2003.

[2.6] My initiation as an archive elf began in this golden era of eFiction, and the SWG archive opened as an eFiction site, emerging amid dozens of archives that had already done exactly what I was trying to do. Help and mentorship were available, and the eFiction forum hummed with activity. No matter how new and untried my skills were, building and opening an archive seemed attainable, even for me.

[2.7] The archive landscape looks very different now. As figure 1 shows, of the dozens of Tolkien-specific archives that once existed, only five had any stories posted in 2022. Most have closed entirely.

[2.8] One by one, the archive elves have been taking ship. They have begun to fade.

3. Invisibility, by design

[3.1] Coppa's term "archive elf" is inspired because it operates well on multiple levels. It connotes the secret and unseen: the elves of northern European folklore who tiptoe out at night to enact minor repairs while people slumber, unaware. It carries the implication of unrelenting labor, cheerfully done. And it suggests magic, a quality that elves possess in the myths and folklore about them (including Tolkien's). The tasks of elves are beyond our mortal ken, so much that we do not even bother to fathom them. We just accept their introduction of minor magic into our lives.

[3.2] The life of an archive elf is much the same. We strive for invisibility, by design. Russandol, my co-administrator on the SWG, and I wait together until we see no one on the site and spirit through our tasks so that, by the time the next visitor wanders in, whatever needed tidying or repairing has been done. And it is unrelenting, the tidying and repairing. A lot of times, no one even notices anything has gone wrong, much less that we have been through to fix it. When we must occasionally report on our work, the reactions we receive are of trepidation and awe: "I could never do that, what you do."

[3.3] In the age of the fading of the archive elves, however, this is perhaps predictable. The internet landscape is not that of the early to mid-2000s, when what you wanted often did not yet exist, and many rolled up their sleeves and got to work, becoming techno-volunteers or archive elves. Today, you arrive not to a village rising beneath scaffolding but to a gleaming city where the next supertall joins an already busy skyline. The archive elves have been replaced by professional engineers whose projects overshadow our humble endeavors. The internet today has become simultaneously more familiar and more inscrutable. Adding to the allure, archive elves have become a rarity. As I noted above, the number of active Tolkien-specific fan fiction sites can now be counted on one hand. No longer can newcomers to the fandom do as I once did: look around themselves, see our work, and believe it possible for them to do too.

4. Democratization of archive elves

[4.1] In Tolkien's world, the fading of the Elves is presented as an inevitability, the outcome of history having run its correct course. After nearly three decades of online Tolkien fan fiction, the decline of the fandom's community-based archives can likewise feel like a teleological outcome shaped by forces much larger than itself.

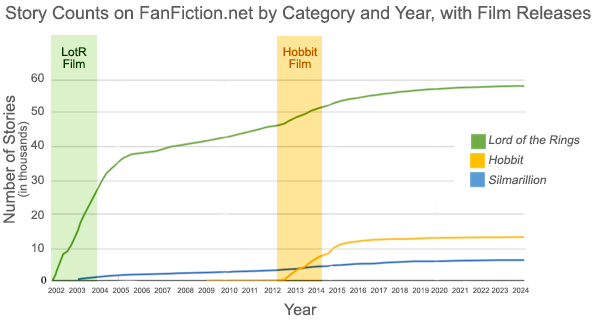

[4.2] Around 2004, the LOTR films were leaving theaters, and the production of LOTR fan fiction began to plateau (figure 2). The archive timeline shows two things happening. First, among those archives opened in the maelstrom that was fandom in the midst of the films, as the intensity of fandom activity started to cool, archives began to go inactive and close entirely. Most of these archives were nonautomated, and visiting them in their final days via the Wayback Machine, I found their update logs teeming with statements: "I promise, soon, new stories, busy, school/work/classes/life, so busy!, but! updates, soon, so much/so many…I'm sorry."

Figure 2. Number of stories on Fanfiction.net by Tolkien source text (Dawn Walls-Thumma).

[4.3] These unfulfilled promises should have sounded a death knell for fandom archives no longer energized by annual film releases, but as figure 1 shows, this was not the case. Instead, after the films left theaters in early 2004, archive building continued, and some film-era archives remained active well past the cessation of the film trilogy, at least partly due to the widespread adoption of eFiction. As I have documented elsewhere, the primary function of the films in the Tolkien fan fiction fandom was in encouraging new Tolkien fans to read and create fan works based on the books, not on the films (Walls-Thumma 2022). As the book fandom remained strong post-film, with book fans often participating in the fandom for many years, the availability of eFiction facilitated archive building for a fandom whose interest in fan works was nowhere near having run its course; nearly three-quarters of the post-trilogy Tolkien-specific archives on the timeline were eFiction-based.

[4.4] However, eFiction also contributed to the survival of film-era archives. Initial use or adoption of automation software, like eFiction, is a strong predictor of which film-era (2001–2003) archives would survive the longest, with nonautomated archives surviving for a median of three years and automated for a median of eleven years (with some still active).

[4.5] eFiction changed what it meant to work as an archive elf by making it a role open to nearly anyone. Previously, becoming an archivist required either skill in coding or the time commitment of manual updates. The new generation of archive elves weren't IT professionals but social workers, librarians, grocery store clerks, and teachers, and the time needed to run an eFiction archive meant that they could continue to produce fan works, interact with fandom friends in their archive's communities, and host events and challenges that generated interest in their archive. Many Tolkien fan fiction communities, therefore, effectively resisted ebbing interest post-film.

5. The elf-lords

[5.1] If those of us who run fan works archives are archive elves, then the developers of eFiction hold a status equivalent to the elf-lords of Tolkien's legendarium: their "magic" greater and more inscrutable than that wielded by the ordinary techno-volunteer. Their work enables not only the creation and sharing of fan works but also the existence of archives themselves, entirely owned and managed by fans free of any institutional oversight. But their work is also more obscure and underappreciated than that of the standard archive elf, the magnitude of that work endowing them with a distance that most archive elves—who are usually also participants on their own sites—don't have.

[5.2] As of this writing, the eFiction entry on Fanlore (https://fanlore.org/wiki/EFiction) is less than five hundred words long, most of it devoted to listing the features of the various versions of eFiction. None of the developers even have a page yet. Likewise, in De Kosnik's Rogue Archives—a book entirely devoted to a study of fan fiction archives—eFiction is mentioned exactly once. Searches of scholarly databases turn up only a few offhand mentions in the fan studies literature.

[5.3] However, eFiction has enabled hundreds of fan fiction archives to exist—probably more. Fanlore lists just over two hundred eFiction archives as of this writing, which is likely a small fraction of what actually existed. Yet this massive influx of fan works, archives, and fan cultures is in danger not just of fading but of being forgotten entirely. By and large, the elf-lords have taken ship. Their fading is well underway.

[5.4] In 2016, the admin team of the SWG's eFiction archive woke up to a scattering of errors due to an overnight upgrade of the site's PHP, the scripting language used by eFiction. eFiction no longer fully worked with the latest version of PHP. This would happen several more times in the years to come, and while we managed to fix the errors each time, with the inevitability of a rising tide, we knew that our fixes would eventually not be enough. We began to research alternatives.

[5.5] Internet archivists acknowledge the paradox of archiving works in digital form. On the one hand, the internet bestows a fearsome degree of permanency—and with it, publicity—on texts intended by their creators to be ephemeral and semiprivate. At the same time, these digital artifacts are frail, their existence dependent on the functionality of multiple technical components that are always grinding toward obsolescence. Only techno-volunteerism, De Kosnik (2016) notes, can preserve digital archives in the long term against the inevitable degradation of digital storage methods. When the work of those techno-volunteers fades, their archives follow. The roaring flames that annihilated libraries in ancient and medieval times have been replaced by the creeping silence of neglect.

[5.6] Despite our diligence and care of the SWG, we never considered what would happen if maintenance of the software at the foundation of that archive ceased, but that's exactly what happened. October 2010 had been the last major release of a new version of eFiction. By the time we noticed the first problem in 2016, the core code hadn't been touched in over five years. What had happened? Why had this software—beloved and used by so many—been allowed to slowly deteriorate and fade?

[5.7] In an attempt to understand the fate of eFiction, I contacted as many of the developers as I could and was able to reach all but Tammy Keefer, who took over after the initial build and did most of the work on keeping the software updated before fading from the project in 2011. The story I heard was a familiar one to me, as someone who has served as an archive elf for fifteen years as of this writing. Indispensability of an archive or codebase and entitlement to the same walk hand in hand, and invisibility can feel like underappreciation, especially when the opportunity cost of maintaining sites and software means sacrificing the creative and social activities that make fandom enjoyable.

[5.8] Rebecca Smallwood, the original developer of eFiction, spoke with me over email on November 30, 2022, and I asked her why she handed over development of eFiction. The plight she described is familiar to archive elves:

[5.9] There's a reason I don't work on open-source scripts anymore! Some people can get very demanding, which when it's a free product, is a lot to deal with. I really had no idea what I was getting into by releasing a script that would become so quickly popular—eFiction caused quite a splash when it was released, and there were quickly hundreds (if not thousands) of sites using the script. I tried my best to make people happy by adding new features and fixing bugs, but realized I was in over my head pretty quickly.

[5.10] Tammy appears to have maintained the software thereafter. She was succeeded in 2014 by Artphilia and Sheepcontrol, who intended to resume development of eFiction with a complete overhaul of its aging code. But that software never fully manifested. In an email to me and echoing Rebecca, Artphilia stated that the demands of the community were too high (December 9, 2022). The project has since been taken over by Tyler Harvey, who like his predecessors, began with an ambitious agenda to offer hosted eFiction sites as well as update the codebase, an opportunity that would make it even easier than it already was to set up a fan fiction archive (email to author, December 1, 2022). Just over a year later, news of the site's development is much more subdued, with Tyler—like his predecessors—seemingly having come to the realization that the project will take far more time and resources with far less community support than he expected.

[5.11] A key theme of De Kosnik's Rogue Archives is the essentiality of the fan labor, the techno-volunteerism, needed to maintain archives preserved using technical tools that are inherently frail. On some level, I believe most people who invest significant time and energy into fan works understand that their archives don't arise from nothing. The more difficult question is how to support this work: the creation and maintenance of sites and software, training and mentorship of archivists, and the support necessary to mitigate the invisibility, loneliness, and drudgery that often comes with such endeavors.

6. Averting cataclysm: A cost–benefit analysis

[6.1] Figure 1 shows that there was a wave of archive closures after the films. This is not terribly surprising, especially given that of the twenty-two archives on the timeline that closed or went inactive in the five years following the films, fourteen of them were nonautomated. There is a trickle of closures in the years that follow, and then 2021 and 2022 hit: a cataclysm. Six archives closed or went inactive in those two years alone.

[6.2] As with the rise of Tolkien fan fiction and the outcrop of new archives after the LOTR films, the slow—then sudden—demise of those archives is bound up with broader internet and fandom history. The late 2000s and 2010s saw both Yahoo! Groups and LiveJournal—platforms used by the communities behind many Tolkien-specific archives—purge content and make decisions that drove fans from their sites. While fans in Tolkien fandom remained on these platforms longer than fans in many other fandoms, activity nonetheless decreased, until the 2019 content purge of Yahoo! Groups left even the most tenacious fan with no choice but to go elsewhere.

[6.3] eFiction-based community archives faced an assault from two sides: Their underlying communities were shut, and their software was decaying. Of the six latest to close, five were eFiction sites and four had affiliated Yahoo! Groups. At the same time, two new sites emerged: In late 2009, AO3 entered open beta, and in 2012, fans began to widely adopt Tumblr as a fannish platform (Morimoto and Stein 2018), a process amplified in the Tolkien fandom by the concentration of fannish activity on Tumblr around the new The Hobbit (2012–2014) films. The presence of thriving, active fannish places to relocate to reduced the urgency around the dwindling Tolkien-specific archives and became, however inadvertently, a third assault on their existence.

[6.4] Closure wasn't the only choice, but the cost in time, energy, and opportunity of averting cataclysm was not insignificant. In late 2019, Russandol and I selected Drupal, an open-source content management system, as the SWG's new software. While I'm sure we were not the first to build a fan fiction archive in Drupal (the Organization for Transformative Works considered Drupal as the software for AO3, for example), none of our hypothetical predecessors left much in the way of instructions. Drupal was no eFiction, which some archivists bragged allowed them to have an archive up and running in less than an hour. The road forward was dark and offered no surety of arriving at our destination. For two years, we devoted hundreds of hours to learning Drupal, rebuilding the SWG site, and porting over its more than 3,500 fan works from eFiction. Because we had an active archive, the benefits, for us, were worth the cost. But for archive elves who watched their sites slowly atrophy and become forgotten, the calculus was understandably different. Some of them migrated to Open Doors; others still linger, their sites unused; and still others simply let the hosting run out and, without warning, their archives go dark.

7. Resisting invisibility

[7.1] In the LOTR films, the fading Elves drift toward their ships, gray-clad and so slow as to appear nearly insensate. In the books, however, not all Elves passively accept their fading. The realms of Rivendell and Lothlórien were preserved from fading due to the eponymous rings worn by Elrond and Galadriel. Although these rings are tangential with the evil of the One Ring, we are given to understand that the motives of the Elven ringbearers—to preserve a cherished space from the atrophy of time—is a more innocent and sympathetic impulse.

[7.2] Writing of the value of "strong central archives" (plural), Versaphile declares: "We must serve ourselves, and rely on each other, because we share the same collective values and goals, and because we seek to preserve our own culture and history" (2011, 14). The history part we seem to manage fairly well—Open Doors, Fanlore, Save Yahoo! Groups, and the Internet Archive, among others, have saved history that would otherwise be lost—and AO3 meets part of the need for living fandoms, but just as at the end of LOTR, the heroes' triumph is dampened by the Elves taking ship, so must the loss of living cultures be acknowledged. If we value these cultures, we must regard them as more than artifacts for future preservation but also facilitate their survival.

[7.3] The quiet disappearance of community archives is likely intensified by the invisibility of archive elves' work that, in some cases, we the elves have deliberately enabled. If we wish fan cultures to survive, they must have their communities and therefore archives apart from the all-inclusive agora represented by AO3. While the dissolution of small archives comes amid a welter of historical and technical factors, the lack of accessible technology is one obstacle—and a surmountable one—but if this work remains invisible, it will likely also be regarded as unimportant. By supporting the work to make archive software accessible, we not only preserve the past but also allow fan cultures to sail forth, not to wester and fade, but to survive into the future.