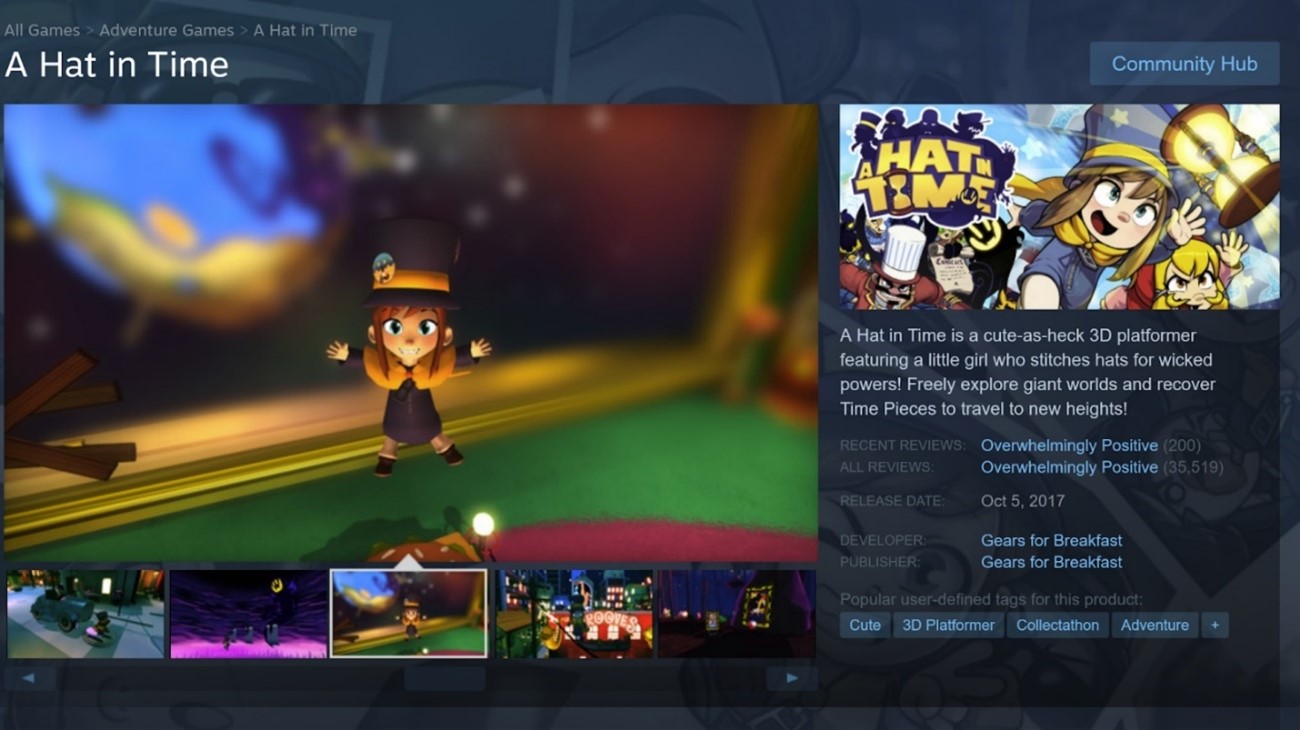

1. Introduction

[1.1] On my computer, I play as Shrek, the protagonist of the eponymous 2001 film (directed by Andrew Adamson and Vicky Jenson), riding a vehicle from Mario Kart, the racing video game franchise, through a level from Sonic Adventure (Sonic Team, 1998), a 3D platforming video game (figure 1). While this amalgamation of 1990s to 2000s media texts might seem like the result of a popular culture crossover blockbuster, it is in fact an image from an indie video game called A Hat in Time (AHIT) (Gears for Breakfast, 2017). On the surface, AHIT is a 3D platforming video game with its own lore and characters centered on Hat Kid, a young girl who jumps around colorful worlds. Through the design of its gameplay, characters, levels, and music, the core (developer-made) text of AHIT is reminiscent of popular video game franchises of the 1990s and 2000s, such as Nintendo's Super Mario 3D games (1996) and Sega's Sonic the Hedgehog 3D games (1998). With the help of player-made mods, however, AHIT goes from being an homage to that genre to being a customizable recreation of specific texts—from simulacrum to simulation.

Figure 1. Shrek, Sonic, and Mario mods used in A Hat in Time.

[1.2] The term 3D platformer (sometimes known as the collect-a-thon or mascot platformer) refers to games in which a protagonist completes challenges by moving through three-dimensional space to reach an objective, often by running, jumping, flying, or other mechanics. Several popular video game franchises either began as or expanded into 3D platformer games in the late 1990s and early 2000s, including Crash Bandicoot (Naughty Dog, 1996), Sonic the Hedgehog (Sonic Team's 1998 game Sonic Adventure), Spyro the Dragon (Insomniac Studios, 1998), and Sly Cooper and the Thievius Raccoonus (Sucker Punch Productions, 2002) among many others. The genre is especially associated with video game consoles of the same era, such as the Sony Playstation (released 1994), Nintendo 64 (released 1996), and Nintendo GameCube (released 2001). By the mid-2000s, however, the mixed critical reception of high-profile 3D platformer games like Donkey Kong 64 (Rare, 1999) led fans and critics to declare the genre dead (McElroy 2013; Bernstein 2013).

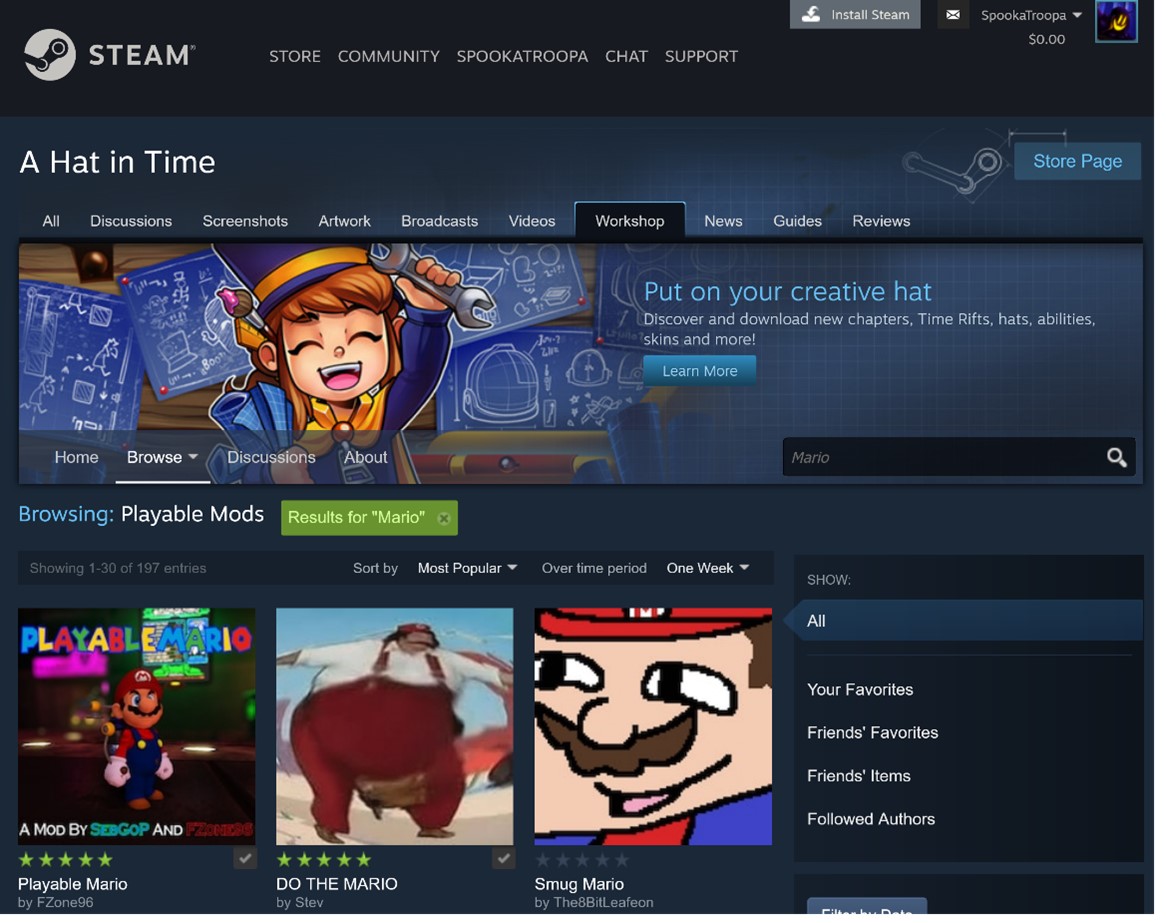

[1.3] The genre's so-called death was also marked by nostalgia for its older texts, as throughout the 2010s and 2020s many fan and game publications listed 3D platformer games of the 1990s and early 2000s as the greatest games of all time (IGN 2022; Fitzpatrick et al. 2016). Starting in the late 2010s, several games capitalized on this nostalgia for the so-called dead genre. Newer 3D platformer games such as A Hat in Time, Yooka-Laylee (Playtonic Games, 2017), Here Comes Niko! (Frog Vibes, 2021), and Demon Turf (Fabraz, 2021) began to recreate the gameplay, design, and aesthetics of older games but also updated them with a bevy of new characteristics and features, such as intertextual references to the older games, crossover cameo appearances from characters of newer games, and online capabilities such as the modding we discuss in this article.

[1.4] Fan practices such as modding, or modifying a game, push AHIT beyond being merely evocative of older platformer games. Modding is a common video game practice in which fans edit the code of a game to add any number of changes, from playable levels to aesthetic tweaks to new abilities. While many companies actively try to stop the modding of their games through lawsuits or other means, AHIT encourages players to mod it both in the game and in its paratexts. The game's release on Steam, an online gaming storefront, includes a modding-tools app, which helps fans edit game files and upload mods for others to download (figure 2). Steam hosts more than five thousand playable AHIT mods, not counting mods available from various other sources (figure 3).

Figure 2. The Steam page for A Hat in Time.

Figure 3. The Steam Workshop page for AHIT, showing the download pages for mods that reference the Super Mario franchise.

[1.5] Many of AHIT's fan mods recreate aspects of specific media texts, particularly the 3D platformer games that AHIT itself is evoking. Hundreds of AHIT mods are recreations or parodies of a number of 1990s and 2000s popular-culture franchises and genres and add playable characters, music, or levels from preexisting games, TV shows, and films. This makes AHIT itself a platform for nostalgic creations in which players can mix and match mods to create their own popular-culture mashups with an emphasis on the popular culture of the 1990s to 2000s—such as the combination of the characters Shrek, Mario, and Sonic. Therefore AHIT is an example of both convergence culture—a concept that denotes both "the flow of content across multiple media platforms" and "migratory behavior of media audiences" (Jenkins 2008, 2)—as well as what Summers calls "authorial intertextuality, or "a reference consciously made by one text to another which is both deliberate and explicit, meant to be perceived and understood by a section of readers and interpreted in a certain way" (2020, 7). AHIT leverages convergence culture, gaming platforms, and intertextual references to produce nostalgia not only for the individual games and transmedia franchises mentioned above but for the genre of the 3D platformer itself.

[1.6] AHIT is a platform(er) in multiple senses—it is a platformer game and it is a media platform. In "Platform Studies: Frequently Questioned Answers," Bogost and Montfort (2009a) define a platform via several criteria, one of which is programmability: "If you can program it, then it's a platform. If you can't, then it's not." Several platforms enable the creation of nostalgia highlighted in this piece. The first of these are nigh ubiquitous: the internet and computing generally. At the next level, Steam and Discord, a social media site associated with gaming cultures that fans use to discuss AHIT modding, are widely accepted platforms that facilitate gameplay and discussions thereof, respectively. Modders take advantage of the programmable aspect of AHIT to create mods that continue the game's nostalgic discourses. This in turn complicates traditional media categories such as production, text, and reception, as AHIT is a text that is constantly being (re)produced by fans, producers, and prosumers (Hong 2013), which is why we examine the full media circuit around AHIT (D'Acci 2004).

[1.7] The ethos of nostalgia permeates AHIT and makes the game—and many other contemporary video games like it—useful case studies in the cultural production of nostalgia. As players insert elements from Shrek, Sonic the Hedgehog, Super Mario, or any number of other franchises into the game, modders valorize certain cultural artifacts and the ideological meanings of those texts, essentially making a canon of popular culture. These practices show how canons "provide a shared pool of resources for scholars, practitioners, and fans" while also "obscuring or devaluing of materials and people outside of a canon" (Cook 2020, 95). This can have ideological consequences, as scholars such as Hassler-Forest (2020) have argued that nostalgic texts come with an "ideological payload" (179). The texts that appear as AHIT mods are not necessarily an important part of our cultural history, but rather they become important cultural artifacts through their appearance in texts such as AHIT that construct histories of popular culture. Using the affordances of contemporary online platforms, AHIT merges the construction of such histories with dynamics of play and postmodern remix culture.

[1.8] AHIT forms a case study in our argument that contemporary media platforms allow consumers, players, and fans to construct nostalgia and cultural canons in a uniquely postmodern way through intertextual and convergence culture discourses that blur text, production, and reception practices. Because this construction of nostalgia is based on the interaction between technological affordances and the cultural discourses around the game (as seen through advertising and other paratexts), methodologically we examine trends in multiple arenas of meaning-making involved with the game; as discussed in our methods section, this includes examining the game's database of mods, statements from producers, and fan commentary to fully outline the circuit of media at play.

2. Literature review

[2.1] A Hat in Time acts as a platform with both technological and cultural affordances that players leverage to construct nostalgia for 1990s to 2000s popular culture.

[2.2] In our analysis, the term "platform" not only refers to an element of AHIT's genre but also functions as a type of media tool. Platform studies has been imbricated with games and game studies since its inception. Ian Bogost and Nick Montfort's work Racing the Beam (2009b), on the Atari 2600 game console as a platform, kicked off the platform-studies project. Platforms are, as noted above, characterized by programmability. Further developing the scope of platforms, Bogost and Montfort (2009b) argue "there are many ways to slice platforms, but certainly, the ones that are most likely to be culturally important are those that are most accessible to people, that have interesting capabilities, and that specifically welcome developers" (n.p.).

[2.3] We present Bogost and Montfort's definition here to ground our approach not to limit or exclude contemporary understandings of platforms. Bogost and Montfort gesture at the expansive potential of the concept in their piece, saying "Rather than asking 'Is it a platform?' we might ask…'Does the system have unique or innovative features as a platform?'" (2009a, n.p., emphasis added). This privileging of platform-ness as an approach rather than as a strict definitional category gives the concept of the platform, and thus platform studies, incredible flexibility. Platform studies has been and continues to be a popular approach, as evidenced by the ongoing book series with MIT Press (currently standing at twelve titles, including one released in 2022) and indeed by this special issue.

[2.4] However, platform studies is not without its shortcomings. In brief, platform studies has a tendency to at best overlook and at worst erase the importance of humans and cultures. Despite a brief assertion to the contrary (Bogost and Montfort 2009a), platform studies is generally seen as a technical approach first and foremost. Two specific critiques are worth highlighting here. Thomas Apperley and Jussi Parikka's "Platform Studies' Epistemic Threshold" (2015) works through a thorough list of platform studies' critics contemporary to their own work, showing how platform studies requires an epistemologically stable platform-as-subject, and discusses how this requirement can limit platform studies. One important aspect of this limitation is the fact that platform studies prioritizes material archives over human experiences. In her feminist approach to platform studies, Anable (2018) centers this critique and notes in platform studies, "the player's body, identity, and audiovisual representations are peripheral to the primacy of the hardware" (135).

[2.5] Our work in this piece keeps these critiques in mind by virtue of its subject and its method. A Hat in Time is characterized by a fuzziness: genre, other games, player-made mods, and the infrastructure used to discuss and distribute these mods are as important to the game as the game itself. Unlike so-called classical platform studies, with its tight focus on a stable (often materialized) object (e.g., the Atari 2600), our work uses contemporary understandings of platforms to expand beyond the limitation that Apperley and Parikka mention. Methodologically, by engaging in a humanistic, self-reflective approach to fan practices and by centering nostalgia, an immaterial, affective domain, we are responding to Anable's feminist critique.

[2.6] An important impact of platforms is that "technologies, including digital games, embody ethical and political values, and that those who design digital games have the power to shape players' engagement with these values" (Flanagan and Nissenbaum 2014, xii). Woodhouse (2022) argues that fans use social media sites such as YouTube to create content that "helps fans imagine their communities by telling stories about who belongs and what modes of fandom are accepted" (¶ 0.1). Using these infrastructures, fans turn such "semiotic productivity into some form of textual production that can circulate among—and thus help define—the fan community" (Magpantay 2022, ¶ 4.2). Postigo's (2007) discussions with modders specifically found that they were often motivated by "a desire to contribute to their communities" (309).

[2.7] Nostalgia can similarly represent and influence our cultural values. Boym (2001) defines two types of nostalgia: a "restorative nostalgia," or a perspective that valorizes the past and seeks to recreate "the lost home," and a "reflective nostalgia," or a perspective that accepts a loss of the past and foregrounds "the imperfect process of remembrance" (42). Building on Boym—as well as other work on nostalgia by Jameson (1991) and Dumas (2012)—Hassler-Forest (2020) argues that a major trend in US popular culture is a restorative nostalgia that valorizes "the neoconservative politics of the 1980s" and "1950s small-town America" (183–84, 179). Texts such as Stranger Things (Netflix, 2016–), Star Wars (1977), and Back to the Future (1985) are held up as cultural touchstones today in part because of how they call back to this era either via their setting (e.g., Stranger Things) or era of production (e.g., Back to the Future). While less romanticized visions of the country's past are present in US popular culture, Hassler-Forest (2020) posits that many widely popular blockbuster texts are "cultural expressions of a reactionary socio-political movement" that idolize neoconservatism and ultimately "white-supremacist politics" (179). Jacobsen (2020) posits that because of this potential for a love of the past to be isolating and reactionary, "nostalgia, it seems, has some earned itself a rather bad name" and has become a term associated with a lack of "progress, advancement or future-orientation" (1). He argues that scholars too often overlook "nostalgia as a positive valorisation of the past" (2).

[2.8] Similar analyses of the ideology of nostalgia can apply to the 1990s to 2000s popular culture texts that are recreated in AHIT mods. To consider a few examples: More than one hundred AHIT mods recreate large portions of various Sonic the Hedgehog video games, a franchise that was designed to elicit "the cultural zeitgeist of the early nineties"; the titular character was based on the public personas of 1990s figures such as musician Kurt Cobain, athlete Michael Jordan, and former US president Bill Clinton, specifically to achieve "success in the United States" (Harris 2014, 76). Mods also recreate characters and settings from SpongeBob SquarePants (Nickelodeon, 1999–), a show that Fuller (2019) argues represented a "culture of innocence and escapism" in early 2000s television (79). AHIT mods also draw from Shrek, a franchise that found early 2000s success through an embrace of postmodernism as seen through its many popular culture references; Shrek demonstrated the "deliberate and explicit manipulation of intertextuality" and now finds itself as a reference in another postmodern text (Summers 2020, 2). The potential of AHIT's mods lies not in their perfect recreation of any one of these texts or endorsement of a particular ideological view but in their ability to mix and match all of these elements as players see fit.

[2.9] Mods are often made by fans and thus could be considered a transformative work or a reception practice but also impact the game itself and therefore have a textual element. This intentionally blurred line between game text and fan activity gives fans more agency but also allows for their further exploitation as fans perform "uncompensated labor" and risk "abandoning the critical traditions of fandom" (Stanfill 2019, 197). The relations that result from this kind of blurriness have been theorized as playbour (Kücklich 2005) and free labor (Terranova 2000). This dynamic "allows corporations to extract more value from participatory activities" (Hong 2013, 984). While AHIT developer Gears for Breakfast has occasionally compensated modders and formally purchased at least two mods to incorporate into the primary game (Gears for Breakfast 2023, 2018), the overwhelming majority of the more than five thousand mods on Steam seem to represent unpaid labor. In AHIT, technical affordances invite modding, while cultural and aesthetic affordances (e.g., game genre) invite nostalgic connections. These two affordances align to create a particularly potent site for fan playbour to be simultaneously valorized and exploited.

[2.10] While mod-making gives AHIT much of its cultural, nostalgic potential, such practices need to be understood in the broader context of the work. AHIT's nostalgic mods did not arise randomly but are in many ways promoted by other aspects of the text and related paratexts—such as nonmod gameplay choices, marketing materials, and producer interviews—that encourage prime players to engage with the game in terms of nostalgia. Therefore we draw on D'Acci's (2004) circuit of media studies for both theory and method. This approach seeks a holistic understanding of a given text through an examination of the text in terms of "production, cultural artifact, reception, and sociohistorical context" (431). This is especially relevant to the ways in which a text "mobilizes conjunctions of economic, cultural, social, and subjective discourses," such as the nostalgia at play here (433). In keeping with this idea, we examine the discussion of nostalgia in multiple sites of AHIT—including comments from producers, the games themselves, and the reception practices of fans—to examine how games and platforms are involved in producing nostalgic politics and histories.

[2.11] We synthesize these perspectives from fan and platforms studies. Within platform studies, scholars such as Noble (2018) and Woodhouse study algorithmic search engines by doing "targeted keyword searches and carefully analyzing" the results to show the interactions of "business imperatives, encoded biases, and fan culture" (Woodhouse 2022, ¶ 4.2). However, a database of mods is unique because "fan works are so rarely the type of creative content that a platform was initially created to support, facilitate, or host" (Alberto 2020, ¶ 2.6). Therefore we integrate platform studies methods with fan studies paradigms through a focus on "fans in their role as platform users" (¶ 2.6).

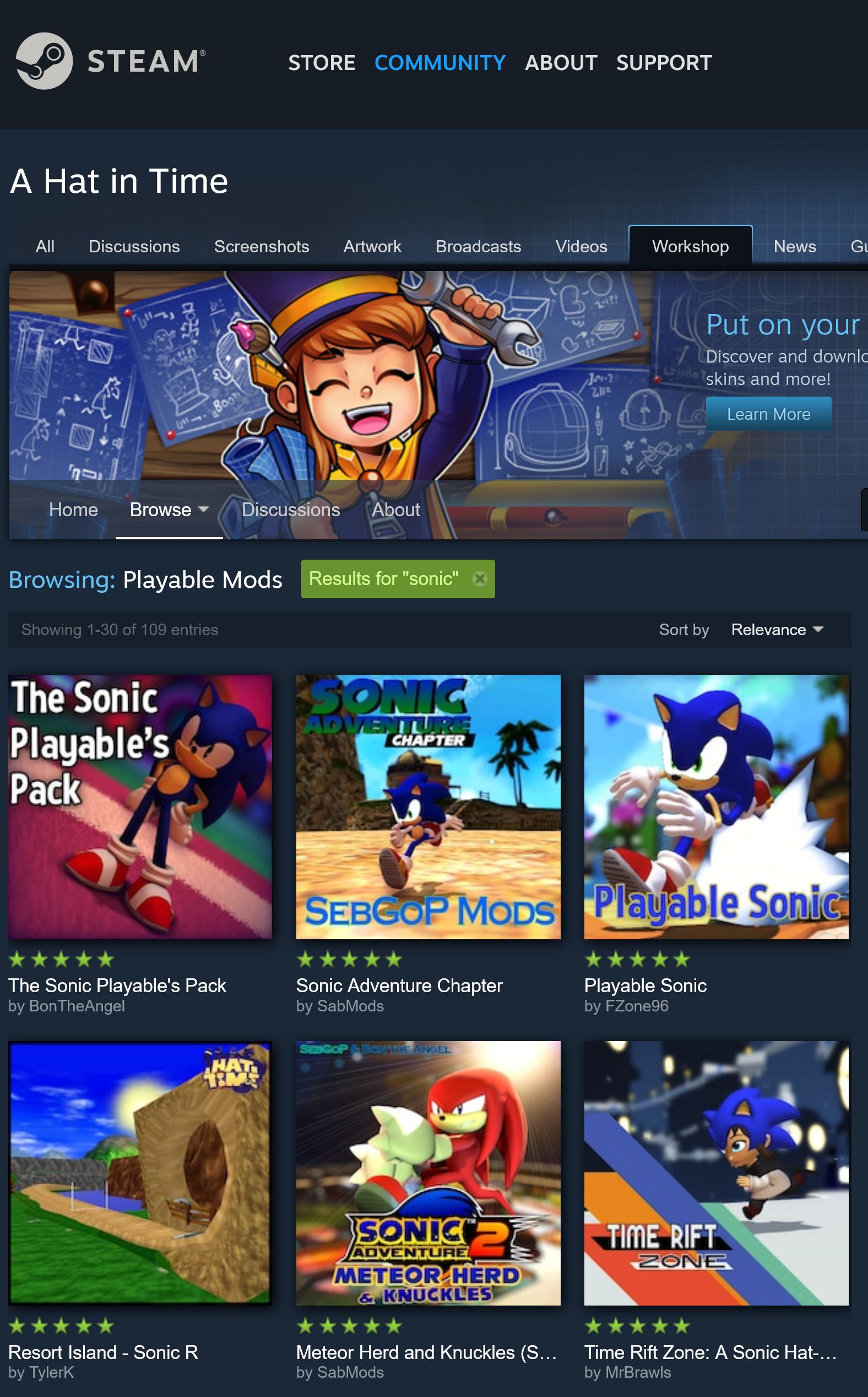

[2.12] Methodologically, we performed targeted keyword searches on AHIT's Steam database of more than five thousand mods. We searched for references to 1990s to 2000s texts, such as Mario, Sonic, or SpongeBob, as well as terms such as nostalgia and retro; through this method we saw previews of hundreds of player-made mods, which often contained written explanations and screenshots of the mods in action (figure 4). We also more closely examined more than fifty of these mods by examining the download pages, which contain descriptions and fan comments, and by downloading the mods to test the in-game effect. We analyzed official paratexts (such as developer tweets), advertisements, and press kits (found from the developer website). Through all these sources we noted trends in how the mods, texts, or paratexts commented on nostalgia, such as through explicit statements about the game being nostalgic or elements that reference preexisting texts.

Figure 4. A search for the term "Sonic" on the AHIT Steam Workshop page returns more than one hundred mods containing references to and recreations of Sonic the Hedgehog content.

3. Constructing nostalgia in A Hat in Time

[3.1] A Hat in Time demonstrates how contemporary media platforms can produce nostalgia and cultural histories. Our study is grounded in a circuit of media studies approach and examines the ambiguous boundaries between text and paratexts at play. Rather than imposing strict categories upon the various phenomena under discussion, we examine the nuances and overlaps of the game's marketing, nonmodded primary text, and player-made mods.

[3.2] A Hat in Time constructs a nostalgic narrative and history through its marketing. The branding of the game regularly evokes the memory of previously popular 3D platforming games. For example, the official Twitter (now known as X) page describes the game as "a cute-as-heck 3D platformer and a GameCube loveletter," referencing Nintendo's early 2000s video game console (@HatInTime 2022). Similarly, the game has been marketed with posters that parody the marketing for the Nintendo 64, a console released in 1996 (@HatInTime 2021). The developers themselves also encourage such nostalgic readings of the game. The press kit offered by developer Gears for Breakfast describes the company itself as "a small team setting out to make a game inspired by the games we grew up with" (McElroy 2013). AHIT developer Jonas Kaerlev also describes the game by saying "collect-a-thon platformer genre is dead" and AHIT "is trying to revive it" (quoted in McElroy 2013).

[3.3] The primary, nonmodded text of AHIT itself continues this centering of nostalgia. Many in-game items leverage players' experiences with older 3D platformers. The Nostalgia Badge item, for example, reduces the game to 240-pixel graphical quality, giving a blocky appearance reminiscent of 1990s video games. The item's in-game description reads "Everything is better when it's worse!," a playful mockery of older video games that invites the player to feel a fond sense of nostalgia for both AHIT and the games being parodied. Other in-game items like the Retro Badge or REDtro VR Badge apply variations on this effect. Similarly, the game's dialogue and cutscenes pay homage to numerous, more specific features of a variety of popular games, such as Super Mario 64 (Nintendo, 1996) and Psychonauts (Double Fine, 2005).

[3.4] AHIT's fan culture continues this association of the game with nostalgia for older texts through mods. The primary, nonmodded text of AHIT encourages modding: upon starting the game players are shown a curated selection of recent mods they can download, and there is a virtual room within the game itself that players can visit to discover and play mods. Of the more than five thousand AHIT mods available on Steam, more than two hundred contain some reference to Mario, more than one hundred contain some reference to Sonic the Hedgehog, and hundreds of other mods reference a variety of transmedia early 2000s shows and franchises such as Kingdom Hearts (Square Enix, 2002), SpongeBob SquarePants, or Shrek, among many others. These mods add any number of elements from the other games into AHIT, from character models to music to playable portions of the older games. Each of these mods in turn has varying levels of nuance: some character mods change the look of the player character, while others also add abilities or gameplay options from the game being referenced. Mods such as "Playable Sonic" and "Playable Mario," for instance, swap player character Hat Kid for recreations of the other respective characters (FZone96 2020; FZone96 and SabMods 2020). These character-change mods often go beyond simple visual swaps and change gameplay: mods such as "Cappy Cap" (Camb0t, MelonSpeedruns, and Crash 2017) and "FLUDD 4-Pack (+ Bonus Remix)" (Camb0t, Xandersilk, and MelonSpeedruns 2018) add items from Super Mario Odyssey (Nintendo, 2017) and Super Mario Sunshine (Nintendo 2002), respectively, that also change how the player character moves. Other mods swap the AHIT soundtrack for that of other games (Catwish 2020; KaptinDragon 2022). Many mods, such as "Harry Potter 2 PC Game Remake Demo" from UnDrew (2020), are almost complete remakes of preexisting texts and make AHIT difficult to distinguish from the games in question. There are also numerous examples that exist in between, such as two mods by SabMods that add most of the levels from 1998 platforming game Sonic Adventure into AHIT but also incorporate AHIT characters and mechanics into the Sonic story, thus resulting in an amalgamation of the two games. Because of the intricate nature of many of the level-recreation mods in particular, mods in this game are often called ports, the gaming industry's term for a transfer of a preexisting game to a new gaming system—a MothraBlaze mod (MothraBlaze 2019), for example, or one from TylerK (TylerK 2019). While "port" typically refers to an official rerelease of an old game for a new console, the AHIT mod community applies the term to mods that feature particularly in-depth recreations of old games, as if to imply that these are official remakes. As previously mentioned, players can combine mods, which can result in novel combinations of assets, levels, and characters from multiple franchises and games, such as the scenario of playing Sonic Adventure as Shrek in a Mario Kart vehicle (which involves mods from Crash in 2019 and SabMods in 2019 and 2020).

[3.5] Many fans describe their mods in nostalgic terms. The mod "Super Nostalgic Time" replaces much of the AHIT soundtrack with that of Super Mario 64 and on the Steam Workshop is described as "40+ remixes sure to send you down memory lane!" (Catwish 2020). A mod that allows players to play as a character from 1997's Final Fantasy VII, a character rendered in blocky 1990s game graphics, encourages players to "equip the nostalgia badge for maximum effectiveness," thus pairing the nonmod affordances of AHIT itself with player-made nostalgic mods (Purple Penguini 2020). Similarly, mods also reference their own playful elements, such as the "Eldritch Gad" mod that changes the player character into a horror-inspired version of Mario franchise character Elvin Gadd and teases players that he will be rendered "very clearly just as you remember him!" (Salutanis Orkanis 2020).

[3.6] The game's Steam Workshop also hosts fan-written guides on how to make mods, which are key tools fans use to frame modding as a nostalgic practice. Mod guides often include instructions on how to upload preexisting assets into the mod editor, which is how a player could take a file from another game and put it into AHIT. A Steam guide on importing music into the game, for example, uses music from a Sonic the Hedgehog video game as a test case (Starschulz and Master Dimentio 2018). Another guide walks players through importing 3D models into the game using an item from the Super Smash Bros (HAL Laboratory, 1999) franchise as an example (Mashu 2019). Modders can comment on these guides to discuss further, such as this comment on Steam by user Minininja (Mashu 2019): "This guide is awesome its very cool heres the finished product im so proud of myself" along with a link to a mod that adds a version of Link from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (Nintendo, 2003) into the game. Similarly, Yoda2798's comment, "This is a great guide! I made a mod adding an energy sword from Halo using it" references the Halo (Bungie, 2001) franchise (Mashu 2019). Fans continue the game's celebration of nostalgia—and continue their (largely unpaid) production of its text—not only in the mods they make but also in the discussion and sharing of the game's modding culture.

[3.7] Fan interaction and discussion of mods continues via Discord, a social media platform associated with gaming cultures. The AHIT Discord server is a space not only for fans to share advice about modding but also for developer Gears for Breakfast to host what it calls modding jams that ask players to create mods around a concept such as vacation or memories; these jams have often inspired nostalgic mods, as modders interpret them in terms of other games, such as the Super Mario Sunshine (Nintendo, 2002) shirt mod that was inspired by the vacation-themed jam, or the SpongeBob SquarePants and Super Mario 64 mods inspired by the memories-themed jam (BennyBlocker 2020a, 2020b).

[3.8] AHIT combines the affordances of online platforms such as Steam, which allows players to upload, download, and discuss mods, and social media platforms such as Discord, which promote fan discussion and modding events, with contemporary fan practices to create novel nostalgic experiences. The production, texts, and fan reception practices all combine to create a text in which producer and player roles blur to create a uniquely postmodern, nostalgic experience.

4. Analysis

[4.1] A Hat in Time becomes a nostalgic text throughout the steps of the media circuit. The marketing and producer-made paratexts prime players to decode it in the legacy of 1990s to 2000s video games and popular culture. The primary text itself both draws on this nostalgic legacy and conflates itself with fans' own reception practices (and encourages playbour) by promoting mods within the game. Fans endorse this view through modding and fan discussions about mods. This nostalgic discourse is based on the affordances of platforms like Steam and Discord that allow fans to connect with each other, the developers, and mods.

[4.2] Conceptualizing AHIT itself as a platform shows that the game allows the mixing and matching of a wide variety of texts (with an emphasis on 1990s to 2000s popular culture) into a convergence-culture melting pot. This new context scrambles the context and therefore meaning of texts and their "ideological payload" (Hassler-Forest 2020, 179). For example, SpongeBob SquarePants the character may represent childlike innocence and escapism to audiences (Fuller 2019), but in the context of AHIT he can wield swords and weaponry from violent franchises like Halo. Sonic the Hedgehog may have been created to monetize 1990s zeitgeist and evoke the personas of Kurt Cobain and Michael Jordan (Harris 2014), but in the context of AHIT the character becomes a malleable simulacrum. Therefore mods give players the agency to construct their own ideological payloads based on the affordances of online platforms and fans' own (financially exploited) playbour.

[4.3] The nostalgia in AHIT's marketing creates new affective connections and discursive associations with products associated with 1990s to 2000s gaming that at the time were not as well received, thus privileging certain texts in the cultural canon. Consider how fans and critics have generally discussed the Nintendo GameCube—a 2001 video game console that featured many 3D platformers—as a disappointment, based on the console's low sales numbers. The console had a "lack of success" for game developers, and "Nintendo's market share deteriorated substantially…with the GameCube" (Landsman and Stremersch 2011, 51). Online video game publication articles refer to the GameCube as "a commercial failure" (Anderson n.d.); an "unusual console" that "did not enjoy much popularity" (Manelski 2021); and "the failed console that changed the industry" (Robinson 2021). The idea of the GameCube as failure makes it significant that the console is often evoked in AHIT marketing, such as in advertisements that parody the console's marketing and on the official AHIT Twitter page. This shows how fans can rewrite the perceived quality of a text—in the world of 3D platformer fandom and marketing, the console is worth celebrating. This supports Jacobsen's (2020) theorization of nostalgia as a "positive valorisation of the past," as fans used discussion of the GameCube to build community (2).

[4.4] This is not the only way AHIT continues a prosocial, communal nostalgia. From Gears for Breakfast's assertion that the company makes "the games we grew up with" to their promotion of the modding community (which is responsible for producing much of the game's nostalgic appeal), the game is framed in terms of a collective memory of the past. There is also an important distinction to be made between nostalgia for a particular text or memory and nostalgia as a general fondness for the past. Given the sheer quantity of games referenced by AHIT mods, for example, it is likely that players may engage with some element of nostalgia for a text they do not have direct experience with but are familiar with through paratexts and community discourse. For example, a player may not have personally engaged with Sonic Adventure, but they learn that it is a game worth remembering when it is continually evoked by the nostalgic mod community, and therefore they may come to have a fondness for it. This shows not only how nostalgia can facilitate communities but also how communities can spread nostalgia.

[4.5] This discussion of 3D platformers also reconstructs the existence of the genre itself; in other words, by associating itself with the 3D platformer space, the game helps discursively construct the 3D platformer as an existing, culturally relevant genre. The discussion of the GameCube and Nintendo 64 signal to fans—or even nonfans who still see such marketing—that such platforms are historically significant. This is especially notable and nostalgic because AHIT is not actually playable on those systems, so players must seek out other discursive connections to justify the connection between AHIT and the GameCube or Nintendo 64. Players are also encouraged to associate those consoles with the 3D platformer genre, even though that genre reflects only one type of text that is available for those consoles. These connections appear throughout the marketing, text, and mods and discursively occur through play and humor. Therefore, we invite the reader to conceptualize nostalgia as an influential force in postmodern convergence culture through which fans reshape and retrieve their pasts through play while also building new communities.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] In this article we used the 2017 video game A Hat in Time to argue that the discursive, cultural construction of nostalgia occurs through contemporary media platforms. Through marketing, the text itself, and especially its culture of player-made mods, AHIT promotes a nostalgic view of 1990s to 2000s US popular culture, particularly with regards to video games of the era. As a platform itself, it allows players to selectively create and scramble textual meanings.

[5.2] This discussion has three takeaways. First, we must examine how platforms facilitate the construction of shared media cultures and nostalgia. In this case, the online video game platform Steam allows players to easily host and find games and their mods; platforms like Discord promote modding events and practices; and AHIT itself can be considered a platform rather than text due to the way it facilitates mods.

[5.3] Our second takeaway is that nostalgic, personalized memories of the past need not be antisocial or isolating. In the case of AHIT, nostalgia for any aspect of popular culture can quickly connect a player to other texts and fans. For example, a fan of the film Shrek may use the mod that allows them to play as that character, and in the process of doing so also find mods that teach them about multiple other franchises they are not familiar with. In this case developers and fans use such nostalgic mods to build community through platforms like Discord and events like modding jams.

[5.4] Finally, it is important to note how this discussion has complicated traditional concepts of the sites of media production. As noted by scholars such as Hong (2013) and Stanfill (2019), blurring the consumer-producer distinction can feel empowering to fans but also often leads to greater profits for companies at the expense of fans' labor. Methodologically, widely used approaches such as D'Acci's circuit of media studies rely on delineations between producer text and fan reception practices, but much of the appeal of a game or platform like AHIT is how such sites become scrambled. There are far more player-made AHIT levels than levels in the original game, which makes AHIT both a text itself and a platform for the creation of paratexts. Fandom and online participatory culture therefore challenge us to find more nuance in our categories of analysis, both in terms of labor and media sites.

[5.5] Further research on this topic would benefit from interviews with fans and mod creators to understand in greater detail how people engage with media texts in different ways. In addition, as briefly noted in this article, many of these observations apply to other games as well. The 2021 3D platforming game Demon Turf (Fabraz, 2021), for example, offers mods that reference Super Mario 64 and Portal (Valve, 2007). Another fruitful discussion would be the legality and ethics of mods that provide detailed recreations of older texts, in terms of both the unpaid labor of fans and copyright law. Corporations like Nintendo can be notoriously litigious in fighting emulations or unofficial recreations of their games, and AHIT mods often blur the line between homage and remake (though to our knowledge the game has not spawned any such lawsuits). We therefore call for consideration of these phenomena in a wider variety of texts, cultures, and disciplines. Beyond just showing how we construct our shared cultural memories, what this line of inquiry shows us is how adept producers, fans, and consumers are at leveraging contemporary media platforms for surprising uses, no doubt leading to nostalgia for those platforms and platformers themselves.