1. Introduction

[1.1] Boys' love (BL), a subculture involving same-sex male romances and eroticism primarily created by women for women (Meyer 2010), has been incorporated into mainstream commercial culture in China (Zou 2022). Since 2016, almost every year has witnessed the emergence of a BL series that became a hit show on Chinese streaming websites. For instance, in January 2016, Addicted accumulated 100 million views within a month, making it the second-most-watched show on its release platform (R. Li 2016). In 2018, Guardian garnered 2.8 billion views in one month (YiEn 2018). The Untamed (2019) accumulated a staggering 6.49 billion views during its two-month broadcast (Leng and Xu, 2019). Word of Honor was released and received a tremendous number of views and online discussions in 2021. All these highly successful works were adapted from BL web novels. With the popularity of these works, the presence of tech giants behind streaming media became evident as they attempted to further monetize the source material. For example, following the success of The Untamed, Tencent, one of the leading platform companies, leveraged its music, film, gaming, and social media platforms to develop a transmedia universe around The Untamed. This development around BL exemplifies the process through which digital platforms extend their influence into the cultural industry, also known as the platformization of cultural production.

[1.2] Platformization of cultural production is the penetration of economic, governmental, and infrastructural extensions of digital platforms into web and app ecosystems, shaping the production and distribution of cultural content (Nieborg and Poell 2018). Traditional institutional actors such as content producers, advertisers, and other third parties become complementors who depend on the technological infrastructure, business model, and governance framework of the dominant platforms. In the Chinese context, this process was instantiated by Tencent, which introduced a pan-entertainment strategy in 2011. Tencent's transmedia, multiplatform ecosystem relies on its platforms to organize the production and distribution of cultural content by cultivating a fanbase on social media, finding source content with a broad and dedicated fanbase that can be monetized into diverse media formats (http://game.qq.com/webplat/info/news_version3/128/1655/1809/m1652/201203/59781.shtml). Rather than focusing on content per se, the goal of this ecosystem is to establish a dynamic fan economy (J. Li 2020). In practice, the web novel commonly serves as a primary source for this pan-entertainment approach. Tencent has gained control of nearly 80 percent of the Chinese web novel market through investment mergers and acquisitions (China Literature Limited 2017). Its dominance includes the most influential Chinese BL web novel platform and fan community—Jinjiang Literature City (Jinjiang)—which as of May 2023 had more than 61 million registered users with an average daily online time of 80 minutes (Jinjiang 2023). Jinjiang was initially run by fans and financed by fan fundraising. In 2007, it faced a financial crisis due to a lawsuit over copyright infringement. Jinjiang thus sold 50 percent of its shareholding to Shanda Literature, which was the largest Chinese online publishing platform at the time. In 2014, Shanda merged with Tencent to form China Literature Limited. As a result, Jinjiang has become a part of Tencent's pan-entertainment landscape. Correspondingly, BL became an integral part of Tencent's platformized extension in the cultural industry (note 1).

[1.3] Tencent's strategy would not have been possible without close ties to the authorities. Such an association also specifically influences participants in the platform economy. The pan-entertainment strategy was incorporated into the state agenda in the Thirteenth National People's Congress in 2015 (Baidu 2021). The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT 2018, 2) officially supported pan-entertainment as an industry that "is expected to account for more than 1/5 of the digital economy, becoming an important pillar of China's digital economy and an engine for the development of the economy." Such official support was also a reason why more platform companies flocked to platformed extensions. However, the collaboration between authorities and Chinese digital champions should not be overstated (Hong 2017). Frictions arise when the state extends regulation into the business of platform corporations (Wang and Lobato 2019), especially within the media and culture spheres. In the realm of BL-related business, navigating this field is inherently precarious due to its confrontation with two significant taboos in China: homosexuality and pornography. According to Chinese law, homosexual content is categorized as abnormal sexual behavior and falls under the crime of pornography (Yang and Xu 2016). For example, in 2012, the founder of a BL novel website was arrested (Xinhua Net 2012). In 2018, a BL writer was sentenced to ten years in prison on charges of writing and distributing homoerotic content. BL series have frequently faced the threat of removal from video platforms. For instance, Justice in the Dark, an adapted BL web drama, was released online in February 2023. BL fans believe that its sudden release without any promotion was a platform strategy to avoid regulation. However, no further updates were released after the first eight episodes. Neither the producer nor the broadcasting platform explained the sudden suspension, which was reported to be a result of regulatory intervention (Qianchuang 2023). The removals, suspensions, and censorship of BL content highlight the impacts of the genre's entanglement in platformization, which encompasses both the governance of the platforms by the authorities and the governance of users by platforms. In other words, the predicaments around BL represent the intricate interaction between authorities and platform companies in the Chinese context.

[1.4] The precariousness of BL raises questions about the optimistic embrace of emerging platforms as vehicles of participatory society and the shared economy; in particular, concerns about social media engulfing fandoms have long been present (Daros 2021). As platforms emerge as new powerful players challenging traditional economic sectors (de Kloet et al. 2019), they highlight the significance of fan culture and regard fans as crucial collaborators in the cultural industry. This awareness has emphasized the potential shift in the dynamics of cultural production (Gray and Lotz 2012; Cunningham, Craig, and Lv 2019). However, digital platforms have proven less emancipatory than was initially expected (de Kloet et al. 2019). The domination of centralized leading platforms and the co-optation of subcultures by platforms have been of particular concern (Maxwell and Miller 2011). Recent research focusing on Chinese BL fan practices on platforms has deepened these concerns. BL fan practices such as adopting socialist discourse, voluntarily responding to antiporn culture, and even participating in censorship have been widely criticized (Bai 2021; Ng and Li 2020; Tian 2020; Wang and Tan 2023).

[1.5] However, those studies have overlooked the structural changes led by the platformized expansion of digital giants. With the platformization of the cultural industry, online fandoms are limited due to their dependency on mediated platforms. Additionally, the production and distribution of source content have gradually become monopolized by a few major players. The platform dependency of fans further restricts their reactions to the risks of platform governance. In this sense, superficial examinations of Chinese BL fan practices are insufficient given fans' structurally dependent position in the platform economy. Employing a theoretical framework of the platformization of cultural production, I provide a contextual understanding of fans' predicaments. At the intersection of the economic ambitions of digital giants and the increasing ideological control exerted by Chinese authorities, BL is a productive lens through which to view the penetration of the platform economy into various aspects of the cultural industry and fan practices. Simultaneously, Tencent's pan-entertainment strategy provides a mesolevel background that connects the broader trend of platformization with specific changes in the BL genre and within fan communities. In addition, the literature concerning the interplay between platforms and fan communities focuses primarily on singular media formats or particular platforms (Cho 2021; Liao and Fu 2022; Yin 2021; Yin and Xie 2021; Zhang and Negus 2020). Through an examination of Tencent's pan-entertainment strategy, I contribute to studies on the effects of transmedia multiplatform development on fan communities.

[1.6] I first track the development of BL in China, which is an anchor revealing the impacts brought upon BL by platformization, including BL's converge (note 2). I then analyze a platformized BL project, The Untamed, within Tencent's pan-entertainment strategy. This case study illustrates how platforms cultivate and exploit the dependency of BL fans. Following that is a case study of Jinjiang's platform governance, which demonstrates the intricate power relationships between digital companies and state authorities and the impacts on BL. Finally, I argue that in the Chinese context, leading platforms monopolize access to BL media content to generate fan platform dependency. BL fans' dependency on platforms places them at a disadvantage in the vague framework of platform governance that is embedded in China's political economy. Platforms implement arbitrary governance against BL, utilizing unclear guidelines from the authorities as well as the vague legal status of BL. By taking a tough stance on BL, platforms perform compliance with authorities to ensure that they can maintain their business. Furthermore, by providing infrastructure such as reporting functions, platforms create an illusion of power for fans, coaxing them to hand their community autonomy over to the platforms.

2. A brief history of BL in China

[2.1] Seen as providing a resistant space for societally marginalized audience groups to voice their desires (Bacon-Smith 1992; Jenkins 2016; Penley 1991; Suzuki 1998), BL originated simultaneously yet independently in Japanese yaoi and anglophone slash fiction in the 1970s (Thorn 2004). It initially spread to China in the 1990s through fan-built communities that shared pirated translated content, particularly slash fiction based on Japanese comics and cartoons. Later, web novels became the primary form of Chinese BL. The web novel is serialized original fiction written by amateur authors and distributed through digital media. As web novels were incorporated into the emerging digital economy (Ren and Montgomery 2012), BL gained commercial popularity, and fan practices expanded from scattered small-scale forums to public platforms and even social media. BL also converged with international trends, including elements from Japanese and Korean idol culture (Kwon 2015) as well as Western popular cultural phenomena such as Harry Potter, the BBC TV series Sherlock and Hollywood superheroes (Yang and Xu 2016).

[2.2] The convergence of various influences made BL communities diverse and heterogeneous, leading to the development of different forms of self-governance instead of rigid norms. For example, Lucifer—one of the earliest BL forums—implemented a questionnaire to test members' knowledge of BL, ensuring shared backgrounds and consensus among participants. Communities such as Matslash that focused on anglophone media content introduced a classification system to categorize fan creations as G, PG, PG-13, R, or NC-17 (note 3). The communities focusing on Chinese BL explored their own way of self-governance. For instance, Jinjiang not only applied its own classification but also set up the author comments section where authors could further explain their ideas, answer fans' questions, express appreciation for readers, and provide clues to future plot developments. The bond between authors and readers served as an informal institution governing the community. Despite variations, BL communities remained autonomous, without the intervention of external coercive forces. However, such self-governance changed after BL's involvement in platformization. When Jinjiang was acquired by Shanda, the four-layer self-censorship system of Shanda was also applied. The system involves the automatic filtering of sensitive words, a two-tiered manual censorship procedure, a user-based report function, and third-party reviewing groups (Zhang 2014). This marked the beginning of platforms intervening in fan communities.

[2.3] Being entangled in the platform economy exposes BL, once a niche culture, to even greater risks of censorship. Regulation risks, including removal, shutdown, and prison, extend from commercial platforms to gated communities. This is because fans currently depend on commercial platforms for access to source materials even though they can keep fan work within closed communities. Platform dependency serves as a fundamental condition for implementing opaque governance within the online domain. Therefore, before discussing the impact of platform governance on BL, I use the case of Tencent's The Untamed to illustrate how dependency is shaped through platformization.

3. No escape: A platformized BL ecosystem

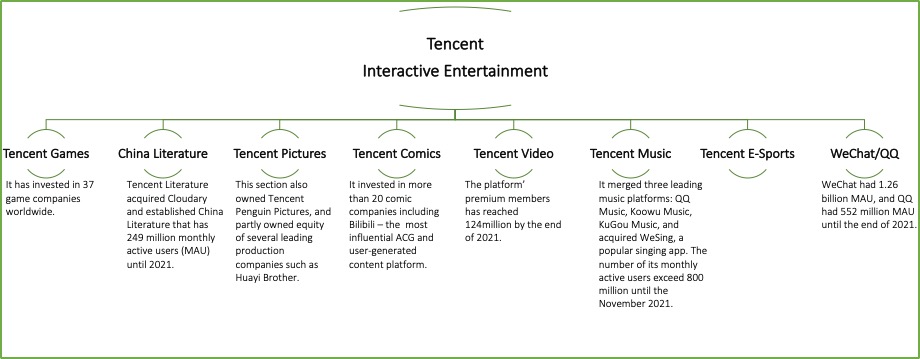

[3.1] Platforms put participants in a dependent position through two mechanisms. First, the platform provides infrastructural access, such as application programming interfaces and software development kits (note 4), to compel producers to align their design and business models with those of digital giants (Nieborg 2015). Second, as aggregators and mediators, platforms can set a pricing structure where one side of the market covers the costs of the other side (Evans and Schmalensee 2016), therefore wielding significant control over the institutional relationships between different actors (Nieborg and Poell 2018). In the case of Tencent's pan-entertainment strategy, the mechanism of cultivating platform dependency of fans is controlling the cultural products that attract them. The base of the strategy is Tencent's expansion in various sectors of the cultural industry (figure 1). The different production and distribution departments are not in a competitive relationship but rather complement each other through the mutual redirection of the user base. In other words, Tencent effectively monopolizes the gateway to a range of online cultural activities, even in niche fandoms, thereby benefiting from a winner-takes-all effect. Consequently, the user base on all platforms serves as the foundation of a product's monetization rather than being specific to any singular production department.

Figure 1. Pan-entertainment strategy of Tencent. Created by the author according to Tencent's public data on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited: Tencent Holdings Ltd. (700) and Tencent's home page.

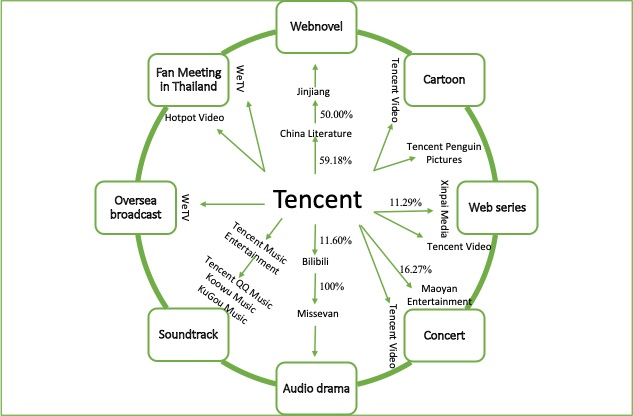

[3.2] The Untamed is a success of Tencent's pan-entertainment ecosystem. The Untamed was adapted from the highly popular web novel Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation (GDC), published in Jinjiang. Before its adaptation into the web drama (the series was broadcast only online), the web novel's appeal had already been confirmed in other media formats. Missevan, a platform indirectly owned by Tencent through equity investment, initially produced an audio drama adaptation, with the first season alone amassing over 200 million plays (Sun 2022). Additionally, Tencent Penguin produced an animated adaptation of GDC, which was released exclusively on Tencent Video and garnered over 3.4 billion views (He 2021). In the multiplatform universe of GDC, the web drama The Untamed achieved exceptional success by targeting not only BL fans but also boy-band enthusiasts. Two male leads in the series came from popular boy bands and had gained fans through variety shows produced by Tencent's subplatform. With its converged fanbase, The Untamed accumulated 6.49 billion views during a two-month broadcast on Tencent Video (Leng and Xu 2019). Tencent Video even introduced a value-added service allowing premium members to pay extra for early access to episodes before the wider release. Despite complaints about the platform's greed, fans contributed CNY 150 million for the last six episodes alone (Xu 2019). Following the finale of the series, the platform further monetized fan enthusiasm by releasing and charging for behind-the-scenes content, particularly intimate interactions between the two leads. The series' original soundtrack was simultaneously released on three music platforms owned by Tencent Music Entertainment Group, attracting fans with unpublished photos from the web drama. Within four hours of its release, the album generated over CNY 2.6 million in revenue (Tang 2019). Two Untamed-themed concerts sold 16,000 tickets within five seconds (Xu 2019). In addition to live shows, fans could watch online livestreams via Tencent Video. More than three million fans purchased concert access (https://ent.sina.cn/tv/tv/2019-11-04/detail-iicezuev7040148.d.html). Tencent also planned three web films, a mobile game, and other derivative products based on GDC and The Untamed (Xu 2019).

[3.3] Furthermore, The Untamed gained international popularity through its release on Tencent's overseas version of Tencent Video—WeTV. It quickly became viral in Southeast Asia, leading Tencent to transplant its business model overseas. Two fan concerts were held in Thailand, both off-line and online, with playback exclusively available on WeTV. The livestream was hosted on Hotpot Video, a short-form video mobile application developed by Tencent to compete with emerging rivals such as TikTok. On the day of the livestream, this previously unknown application became the fifteenth most downloaded app in the iOS App Store (Xi 2019).

[3.4] Regarding the universe of GDC, Tencent's strategy focused more on facilitating the flow of fan traffic across different platforms than on directly managing each production stage. In this sense, platformization operates covertly on the foundation of ownership. Furthermore, Tencent prefers to rely primarily on financial methods to complete its pan-entertainment landscape. For instance, Tencent invested in the production company of The Untamed after the web drama's success. By monopolizing access to all fan objects through its subplatforms (figure 2), Tencent ensured that fans remained tightly attached to its ecosystem and therefore constantly captured, calculated, and monetized the fanbase. The more access Tencent possesses, the more accurately it can calculate fan behavior. Consequently, as fans become increasingly dependent on platforms, their options become limited. This dependency, in turn, serves as the foundation for platforms to target BL in their governance framework, discussed in the following section.

Figure 2. The GDC universe. Created by the author according to Tencent's public data on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited: Tencent Holdings Ltd. (700) and Tencent's home page.

4. Loss of autonomy: BL in platform governance

[4.1] Platform governance refers to how authorities govern platforms, how platforms govern users, and what users expect of platforms (de Kloet et al. 2019). While transnational platform companies tend to establish globally standardized content guidelines instead of local ones (Nieborg and Poell 2018), the interpretation and implementation of these standards often remain vague and lead to controversy (Frenkel, Casey, and Mozur 2018). The prevailing guidelines imposed by dominant platforms result in stringent content control, significant curatorial bias, and limited accountability (Nieborg and Poell 2018). In the Chinese context, the vagueness of platform governance further complicates the intricate relationship between authorities and digital champions.

[4.2] Chinese authorities have adopted a governance model that "restricts direct control over meanings to sensitive political issues and otherwise promotes collaboration and participation in processes of meaning-making" (Schneider 2018, 225). The foundation of this model is the licensing system (Schneider 2018), which creates a sphere in which all players of the internet business can display their loyalty to the authorities (Zhen 2015). More specifically, by issuing or revoking licenses, authorities can require that confidential internet logs and records of everything saved by, for example, internet service providers (ISPs) and internet content providers (ICPs) be checked. Representatives of ICPs must even attend ideological courses to obtain licenses. However, this licensing system is confused, involving many different regulatory departments. Correspondingly, the licenses that online businesses need to operate vary. For example, video streaming platforms such as Tencent Video obtain licenses ranging from a China Internet Integrity certificate to a food trading permit. On the other hand, license regulation is a form of soft cultural censorship, as has been affirmed through vague edicts from policymakers (Cunningham, Craig, and Lv 2019). For instance, the Cyberspace Administration of China requires internet companies to "persist in the correct political orientation, public opinion guidance orientation, and value orientation; and maintain a clean and positive cyberspace." The definitions of "correct political orientation" and "a clean and positive cyberspace" depend on the political astuteness of internet companies (quoted in Cunningham, Craig, and Lv 2019).

[4.3] The vagueness of official policies is a strategic element of governance in China because it allows more people to be frightened and arbitrarily targeted (Link 2002). In the practical layer, vagueness helps authoritarian governments generate an infinite governance responsibility to the extent that when governance is outsourced to platform companies, an inclination toward censorship—typically encompassing panic and risks—can also be transmitted to end users (Schneider 2018). Relying on the licensing system, private companies tend to adopt conservative measures that are stricter than those prescribed by the authorities. Therefore, I argue that in the sphere of platform governance, rather than allowing stakeholders to negotiate, Chinese companies are subjected to unpredictable enforcement, which impacts their bottom line. The arbitrary censorship imposed by Jinjiang on BL content vividly illustrates how this governance model perpetuates uncertainty among end users and its detrimental effects.

[4.4] In April 2014, the National Office against Pornographic and Illegal Publications (the office) launched the annual antipornography campaign (the campaign) on the internet. The office is led by the minister of the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee and supported by twenty-seven government departments. Its mission is to "maintain sociopolitical stability and ideological security" (Yang and Xu 2016), which also applies to annual campaigns. The campaigns, on the one hand, are convenient excuses for tightening ideological control (Yan 2014); on the other hand, they justify the CCP's anxiety that sexual liberalization will lead to political liberalization and that the sexual rights discourse will undermine social stability (Yang and Xu 2016). Therefore, in addition to the crackdown on straightforward pornography websites, online publications such as web novels have increasingly been censored in annual campaigns, and the results have usually been disastrous. For example, in the 2010 campaign, thousands of BL forums, websites, and personal blogs were forced to close, followed by the arrest of dozens of writers and a website owner in the following year. However, the 2014 campaign was notorious for its broad scope and deterrence impact.

[4.5] While both heterosexual romance and BL were endangered by the campaign, Jinjiang regulated BL content specifically and applied more severe measures to BL than to other genres. The platform first locked the "BL" and "BL slash" subsites for a week, preventing readers from accessing them unless they had bookmarked a site beforehand. Authors who were serializing their work during this period lost both their connection with fans and income. A month later, a party-owned newspaper reprinted a BL-related article originally published by the New York Times. The article commented on BL as a sexual revolution with feminist sentiments (Tatlow 2014). Jinjiang therefore perceived it as official dissatisfaction with BL to conduct further censorship of this genre. Jinjiang changed the main section from "BL" to "pure love" and merged it with the "no character-pairing" subsite. Moreover, the platform altered its most active subsite from "BL Leisure" to "Leisure." As an ironic result, BL elements disappeared from the surface of this largest BL community. In contrast, the genre of heterosexual romance that brought real damage to Jinjiang was not specifically targeted (Yang and Xu 2016). Thus, Jinjiang's measures around BL were a performative gesture of kowtowing to the authorities instead of a long-term responsible framework.

[4.6] Jinjiang's frantic response also stemmed from the vagueness of legislation. China's pornography-related law enforcement follows two guidelines issued in 1988 and 1989, which classify "graphic depictions of homosexual or any other abnormal sexual behavior in an obscene manner" as "obscenity" and "pornography" (Yang and Xu 2016). However, Chinese criminal law allows for sexual depictions within the context of medical, scientific, literary, or artistic content without providing precise definitions or standards for these contexts or for literary and artistic value. As web novels are often disparaged as a low genre by cultural elites and mainstream media, defending BL web novels in terms of literary value is virtually impossible. Consequently, under such an inconsistent legal framework, BL is equated with pornography (Huang 2010) based solely on its same-sex theme, regardless of whether it contains sexual scenes. The vague legislation of BL has enabled Jinjiang to rationalize its radical censorship. Specifically, it has allowed Jinjiang to attribute all excessive censorship to the demands of the authorities, even disguising them as necessary measures to preserve BL. As a public letter by Jinjiang's manager hinted, BL had ideological riskiness; thus, fans need to understand and cooperate with Jinjiang's measures (https://bbs.jjwxc.net/showmsg.php?board=17&boardpagemsg=1&id=342956). Such discourse disseminates moral panic about BL among fans, portraying stringent censorship as a glorified form of protection. Furthermore, vague definitions and boundaries of censorship make it challenging for fans to determine truly safe online communities. Consequently, the platform dependency of fans persists despite unfair governance measures in Jinjiang. BL authors, although they can still publish their work on Jinjiang, are compelled to develop corresponding tactics to make the necessary romantic depictions survive, such as utilizing metaphors to portray sexual intercourse and Chinese–English code-switching (Wang 2015). A more aggressive method is moving potentially transgressive texts to other platforms, for example, Weibo and AO3. However, given contractual obligations, economic considerations, the accumulated fanbase, and sophisticated infrastructure (for example, payment systems), most BL authors have not chosen to leave Jinjiang altogether.

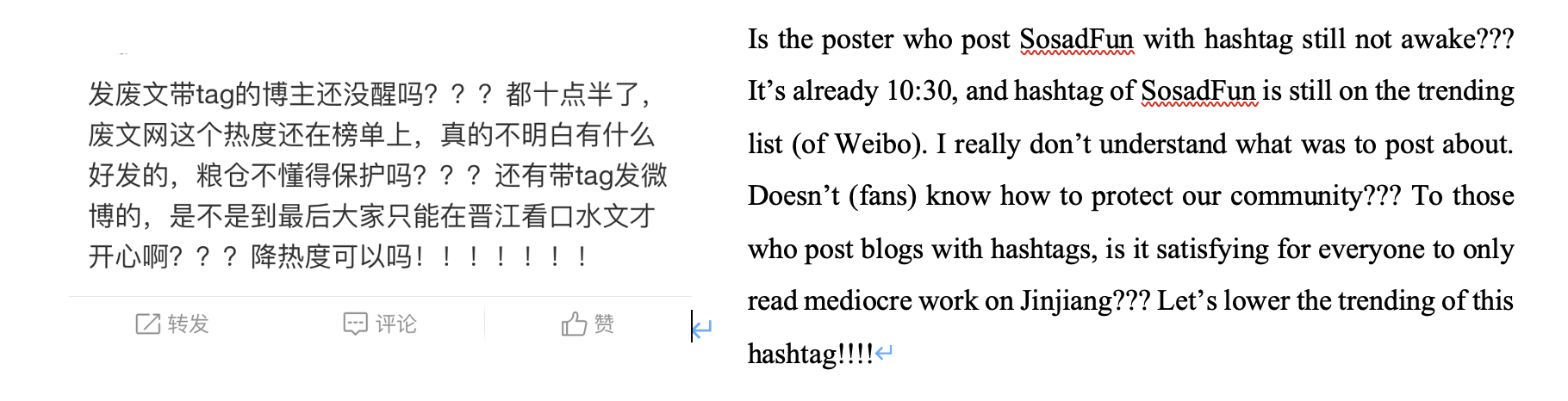

[4.7] The vague governance framework has influenced not only public commercial platforms but also marginal communities. For example, Changpei Literature Forum, a noncommercial BL web novel website (before 2017), advised writers to revise or remove sexual depictions from their works or relocate them to an inner section accessible only to writers. Similarly, Mtslash, a Western slash-focused BL forum, posted a rectification notice on the first day of the campaign. Panic continued even after the official conclusion of the campaign in 2014. Fans remain vigilant as the annual crackdown approaches each year, and authors check their works for potential risks. Readers on social media kindly remind authors to conceal potentially risky content from these public platforms. Members of gated communities also take precautions to protect the niche nature of their sites and avoid attracting attention. SosadFun is a small-scale fan-fundraising BL web novel community that locates its servers overseas and operates on an invitation-based access system. Only internal members have the privilege of issuing codes or links to invite external members to join. Through this gated management, the community ensures its safety. Figure 3 is a screenshot sourced from social media: after a few months of maintenance, SosadFun resumed its operations, and members enthusiastically discussed it on public social media, resulting in the related hashtag on the trending list. The risk of exposing their community to the public eye caused panic among fans so that some fans criticized those who had posted with hashtags and asked for that content to be deleted.

Figure 3. Fan's post about SosadFun.

[4.8] Furthermore, the platform governance of Jinjiang has also generated the public discourse surrounding BL as a morally and legally problematic genre. In the campaign of 2014, Jinjiang issued a self-censorship standard that stated, "Do not write anything below the neck" (Nanfang Zhoumo 2014). In the crackdown of 2019, Jinjiang's manager posted via her own social media that the site was implementing stricter internal censorship standards and urged authors to "embrace Platonic love" (https://www.sohu.com/a/www.sohu.com/a/316142980_114941). These sensationalized measures and statements, amplified through media coverage, perpetuated the association of BL with pornography in public discourse. As Jinjiang is the largest BL community, any changes in its content review standards have a ripple effect through the activities of members on other platforms. Therefore, fans not only succumbed to regulation risks but also relinquished their autonomy to define what they loved. Additionally, all-pervasive infrastructure, for example, the ubiquitous function of reporting, is another way for platforms to take the autonomy of self-governance away from fan communities.

[4.9] The reporting mechanism impacts the self-governance of fandoms in two ways: restricting users' understanding of disagreement and limiting the channels for resolving disputes. These two aspects originally played a significant role in community self-governance. Reporting was formerly a crowdsourced surveillance system that was used by authoritarian regimes during specific periods, such as Stalin's Russia and China's Cultural Revolution (Wang and Tan 2023). Now, it has become a daily channel through the easily accessible reporting button on the platform interface. For instance, Jinjiang's reporting button is prominently displayed alongside two fundamental functions: collect and share, at the top of the page. Every time users hover over the button, they are automatically reminded of this mechanism and reasons for reporting. The everyday availability of reporting, in turn, leads to governance being taken for granted by users overlooking its underlying ambiguity. Furthermore, the grounds for reporting limit users' understanding of the content on platforms. When users click the reporting button, it directs them only to the predefined reasons set by the platforms; for example, "pornography" and "harm to underage individuals" are predefined reasons on Jinjiang. The possible diversity preserved through public communication and negotiation within fan communities has been significantly compressed for those reasons. The reported penalties are severe, ranging from temporary suspension to permanent removal from the platform. Such effectiveness of reporting depends on whether users can appropriately connect the reported object with the reasons provided by the platform. In this process, users might appear to be exercising power. In practice, what happens is that users select the reporting categories specified by the platform to content they dislike. Whether the report is effective and how it is handled is almost entirely at the discretion of the platform. Therefore, using the reporting feature serves to perpetuate the platform's power time and again.

[4.10] Notably, embedding the reporting within the platform infrastructure does not necessarily lead to user-driven censorship. In the case of BL fandom, it is essential to revisit the aspect of platform dependence. When platforms dominate the production and distribution of BL products, provide fundamental social spaces for fans, and preserve the history between fans and fan objects, it is inevitable that platform design shapes fans' practices. When fans practice on a platform that generally categorizes their beloved content as an outlawed object and encourages only one way to resolve disputes—clicking the button to report—the widespread use of reporting is not a surprising outcome. In the case of BL communities, an increasing number of disputes were directed to reporting. For example, Tianyi (Flood 2018) and Mr. Deep Sea (Yang and Ren 2019) were sentenced to ten years and four years, respectively, for creating BL web novels. These conflicts originated from discontented fans pressing the reporting button. The increasing legal disputes around BL demonstrate that fan communities have lost autonomy. Platform infrastructure such as reporting, by creating an illusion of empowering fans, has reinforced platforms' domination and gradually taken over fandoms in a covert manner.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] The platformization of cultural production in China, exemplified by the incorporation of BL into mainstream commercial culture, has profoundly transformed the BL subculture. Tencent, as the dominant player in the Chinese digital industry, has expanded its influence into this genre through their pan-entertainment strategy. By monopolizing access to various BL media formats, Tencent has cultivated strong platform dependency on its transmedia and multiplatform system among BL fans. In the intricate framework of platform governance shaped by authorities and platforms, the dependency of BL fans on platforms places them at a significant disadvantage. The platform conveys vague yet overarching state policy preferences to generate a legally and morally dubious public perception of BL. Consequently, widespread governance risks permeate BL fandoms, extending even to marginalized niche communities. Simultaneously, through infrastructure design such as the reporting feature, the platforms exert control over the public discourse around BL and limit the approach of dispute-resolving. Furthermore, the illusory power presented by the easily accessible reporting feature entices fans to relinquish their autonomy in community self-governance to platform owners.

[5.2] This research contributes to delineating the structural context necessary for comprehending Chinese BL and fan practices. Previous studies have underscored the cooperative engagement of Chinese BL fans with the cultural industry and their voluntary compliance with censorship. For instance, fans adopted socialist discourse to collaborate with institutional producers (Ng and Li, 2020), voluntarily responded to the dominant antiporn culture (Bai 2021), and conformed to official censorship (Tian 2020). From the perspective of cultural production platformization, it has become evident that dependence on centralized platforms has disadvantaged BL fans in terms of platform governance. Risks originating from commercial platforms such as Jinjiang spill over into various dispersed niche BL communities, necessitating caution among fans. Examining the surface compliance and cooperation of fan practices requires considering such structural risks. The offstage practices of BL fans thus call for attention in future research.

[5.3] Additionally, in this article I contribute to understanding how global platformization shapes cultural expression, using fan-driven subculture as a case study. Instead of treating Chinese BL merely as an example of non-Western platforms, I address the vagueness and incoherency of platform governance as a more general issue. While Chinese BL fans' suffering is embedded primarily in the Chinese political economy, it would be overly simplistic to view it as a case of Chinese exceptionalism, as vagueness and potential bias in platform governance are ubiquitous among transnational platforms (Frenkel, Casey, and Mozur 2018), which ironically dictate what is and is not permitted in global everyday life (Jin 2015). The dominance of platforms warrants constant and global critique. Future studies should address the unbalanced distribution of power and the nontransparent governance imposed on end users.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] This research is funded by the Finnish Cultural Foundation.