1. Introduction

[1.1] In the past twenty years, web platforms have introduced and popularized the practice of using user-generated keywords, called tags, to organize information on the internet. One archive of fan fiction, Archive of Our Own (AO3), uses a user-generated tagging system to organize works and facilitate discovery. The general way that people think of organization and categorization is highly dependent on their culture (Bowker and Star 1999). As culture shifts with the growth of online social reading and publishing platforms like Wattpad, Archive of Our Own, and Tumblr, should our description and categorization of books in libraries and in the overall publishing world change? If so, how can we best learn what changes would be beneficial? I propose that developing a method to reliably code the tags creators apply to their fan works will help researchers compare the description and categorization behaviors of social readers across different fannish subcultures, revealing insights that may inform development of genre categorizations, content warnings, and reader recommendation systems.

[1.2] I originally sought to determine whether it is reasonable to assume that tagging behaviors are similar across fandom user groups represented through AO3's curated folksonomy or if more research should be done into emergent "tagging dialects" present among different fandoms, in the hopes that by analyzing the way that fan writers describe their own works when posting them online for others to find, we can gain insight into the way that readers and writers conceive of how their works should be categorized. While designing a study with that goal in mind, I realized there is a need for a standardized system for researchers of different fandoms to categorize tags. Currently, studies that code and organize fan tags commonly build their own coding schema for analyzing characteristics of their tag set (Price 2017; Gyhagen 2022). Developing a standard taxonomy would enable researchers to readily compare tag data among studies from multiple fandoms and platforms and would potentially reduce the time required to conduct a study by eliminating the need for every researcher to induce their own coding schema. Prior work has been done to develop a fan tag taxonomy to analyze tags on AO3, but that taxonomy has yet to be tested on a fandom outside of the one for which Price developed it (Price 2017). In this study, I applied Price's taxonomy to another fandom to explore its application beyond the Marvel Comic Universe (MCU), seeking to answer four questions: (1) To what extent does Price's (2017) taxonomy translate to use in a new fandom? (2) How does tag expression vary between two different fandoms? (3) At what points does the taxonomy fail to describe tags in a new fandom, if there are any? (4) What changes need to be made to develop this taxonomy for pan-fandom use?

[1.3] For this study, I used a Python script to scrape tags from Archive of Our Own and store them as a CSV file. I then coded the tags using Price's fan tag scheme (2017) to investigate the feasibility of applying her schema to tags in my dataset, and I compared my results with hers to reveal similarities and differences between the tagging characteristics observed in our two fandoms. I particularly wanted to see if differences between the use frequencies of tag types could be explained by known differences between our fandoms or if they suggested inconsistencies in coding choices that would need to be corrected in a standardized taxonomy.

2. Designing user-centered classification systems

[2.1] The rationale behind investing effort to study the ways that fan taggers organize their work presumes that information organization is highly influenced by culture. Bowker and Starr, through their examination of a variety of classification systems, assert that classification systems inevitably express a point of view on the materials they organize (1999). By imposing categories of classification, a system expresses assumptions that creators of the classification system have made about their world. For example, Olson points out that the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) specifically list a category "Computers and women" but give no corresponding category for men, expressing the view of the classifiers that computing is associated, by default, with men and also not with women (2001). Each choice made in the design of taxonomies and ontologies inherently "valorizes some point of view and silences another" (Bowker and Star 1999). Some alternatives to top-down information organization structures seek to solve the problem of imposing the worldview of designers by generating bottom-up organization from information found within the documents being organized or their metadata, promising a democratization of organization (Hidderley and Rafferty 1997). One such solution, creating a folksonomy through social tagging, seems to offer some solutions to the problems identified with using taxonomies or ontologies, but it presents new problems as well.

[2.2] On sites like Archive of Our Own, tags allow users to filter searches, narrowing the vast amount of content in online fan fiction collections so that users see only content marked with their selected tags. This process of organization through user-generated tags has been referred to by multiple names, including social tagging (Trant 2009), collaborative tagging (Golder and Huberman 2006; Kipp and Campbell 2006), and collective tagging (Avery 2010). All these labels refer to the same thing—"publicly labelling or categorizing resources in a shared, online environment" (Trant 2009). User tags result in a body of tags that describe the collection, which has been referred to as a "folksonomy" since the term was coined by Vander Wal (2005). The portmanteau of "folks" and "taxonomy" embodies the bottom-up classification built by users through tagging, the antithesis of a top-down taxonomy imposed by subject specialists (Vander Wal 2005).

[2.3] Folksonomies provide a way to organize information in collections that are too large for any one cataloger, or team of catalogers, to index because they spread the work of organization among the users of the information system (Merholz 2004). While other methods of organization, such as the controlled vocabularies used to classify works in a library, provide consistency and arguably more precise recall, they require costly expert design as well as indexer training (Bullard 2018a). Controlled vocabularies also suffer from slow response to changes in user vocabularies and shifts in the collection, which folksonomies incorporate immediately (McElfresh 2008).

[2.4] Folksonomy enthusiasts may see them as a revolutionary organization system that allow users to find items in their chosen vocabulary (Merholz 2004) and that challenge a traditional meta-narrative that respects a single, authoritative voice (Avery 2010); however, folksonomies suffer from some inherent flaws, which have been documented by numerous researchers (Golder and Huberman 2006; Guy and Tonkin 2006; Kipp and Campbell 2006; Munk and Mørk 2007; Noruzi 2006). The main failings of a folksonomy recur throughout these studies: synonymy, polysemy, word form variation, different depths of description, misspelt tags, and single-use tags that have little meaning to most of the community. Additionally, though it is tempting to view folksonomies as democratically decided organization systems, they are not truly so. A folksonomy is a result of many individual decisions, not the reaching of group consensus by the users (Feinberg 2006). The same minority worldviews that are silenced in traditional classification systems may be silenced when they are overwhelmed by the mass of tags created by a majority of users in the system. One of the very flaws folksonomies might aim to alleviate—reinforcing majority worldviews at the cost of differing perspectives—might be as prevalent in this organization system as in traditional classification systems.

[2.5] Numerous computational approaches have been proposed to address the problems inherent in folksonomies, but those approaches introduce their own concerns, including the potential for allocating blame for harmful outputs to the algorithms used rather than a human designer (Crawford 2015) and the tendency of those systems to further marginalize minority views (Aroyo and Welty 2015). Bullard proposes that the major flaws of a folksonomy may be solved using the direct human judgment of users of that system rather than a computational method, a system she describes as a "curated folksonomy" (Bullard 2018b). A curated folksonomy takes the aggregate tags produced by users as a starting point and employs the decision-making either of expert users or the collective users of the system to identify and remedy problems of synonymy and homographs. In this system, users create tags and a human or group of humans combine synonymous tags and differentiate homographic tags, improving recall and precision (Bullard 2018b).

[2.6] The use of human judgment rather than an autonomous system allows for the creation of an organization system that balances increasing findability with the improvement of the experience or collection for even relatively small groups of users. Bullard's research on the complex decisions of tag wranglers on AO3 found that human workers made decisions regarding tag merging or differentiation based on factors that included respect for historic oppression and the avoidance of enacting ongoing forms of harm and oppression (2018b). While some decisions made by human workers are not the "best" decisions in terms of precision and recall in the system, they improve the inclusivity of minority user views in ways that unregulated folksonomies or algorithmically processed folksonomies do not.

3. Research on fandom and fan works in library and information science

[3.1] Within the field of library and information science, research on fandom, fan works, and fan work organization is adding to knowledge about reader preferences and the ways that people not trained in information organization create categories within collections. Fan fiction research has contributed to the understanding of the cognitive science of fiction (Barnes 2015), literacy and writing education (Aragon 2020; Magnifico, Curwood, and Lammers 2015), the reading desires of teenagers and young adults (Moore 2005), effective readers' advisory for users in the digital age (Griffis and Jones 2008; Harris 2020), online communities as a type of small world with constrained information access (Kizhakkethil and Burnett 2019), and the information activities of people engaged in serious leisure (Hill and Pecoskie 2017). This test of Price's fan tag taxonomy builds on research that has used fan work archives to study folksonomic classification and the task of archiving digital artifacts (Bullard 2018a, 2018b, 2016; Gursoy 2015; Price 2019).

[3.2] Tags are a type of metadata, but their usage is not easily separated into the three types of metadata generally seen in digital libraries—descriptive, administrative, and structural (Smith 2007, 63–66). Instead, Smith has identified seven types of tags that comprise the main functions of tags as metadata: descriptive, resource, ownership/source, opinion, self-reference, task organizing, and play and performance (Smith 2007, 67). Price's (2019) research adds subcategories within that framework to more closely examine tags implemented in fan-specific contexts. Her research reveals that tags are used by fans not merely for classification and organization, but also for creative, affective, and dialogic purposes. Tags seem to represent an additional form of user expression, an extension of the writing process for fan fiction authors. This suggests that tags should be researched not only for their effectiveness in terms of increasing findability in a collection, but also for what they tell users about the content in the collection. My analysis aimed to apply comparable methods to another fandom to investigate whether the tagging behaviors found by Price are common across fandoms or specific to her fandom. Newly found behaviors would suggest that changes may be necessary to prepare the fan tag taxonomy for pan-fandom use.

4. The folksonomy of tags on AO3

[4.1] Archive of our Own (AO3; https://archiveofourown.org/) is an online fan fiction archive created and run by the Organization for Transformative Works, which is a nonprofit organization "run by and for fans to provide access to and preserve the history of fanworks and fan cultures." The archive was released as an open beta in 2009 and has grown significantly since then. As of 2022, it has more than 4.9 million users and over 9.7 million works uploaded to the site across 51,960 fandoms. Works are organized according to the tags their author assigns while uploading, but all users may assign tags to works they bookmark. This feature helps a user find a specific work among the collection of works they have bookmarked, but it does not appear next to the work when other users browse the archive; however, any user may perform a bookmark search to find works according to how other readers have bookmarked them. While Price's study of AO3 focused on the tags created by writers, a similar study by Gyhagen examined the tags created by AO3 readers when bookmarking works and explored the cultural dynamics at play in a system where writers can see reader bookmarks as a sort of "hidden feedback" (2022).

[4.2] AO3 provides five types of tags that authors may use to describe their works: Media, Fandom, Characters, Relationships, and Additional Tags, related in the following structure:

Figure 1. Tag structure on AO3.

[4.3] Tag wranglers "wrangle" user-generated tags into canonical tags to reduce the issues of synonymy that arise with folksonomies (Golder and Huberman 2006; Kipp and Campbell 2006; Merholz 2004). The stated goal of tag wrangling on AO3 is not to change how authors have tagged their works, but to "standardize canonical tags and synonym relationships as much as possible" (https://archiveofourown.org/wrangling_guidelines/2). Wrangling does not affect how a tag appears beside a work but rather creates a relationship that directs the search and filtering features on the site to treat the author's tag as the canonical or wrangled tag while preserving the creator's original tag text. Still, tag wrangling likely affects writer choices when tagging their works because canonical tags are suggested via auto-completion as the writer types. It would be reasonable to assume that a higher degree of variation in tag spelling, word order, and capitalization would exist among AO3 tags in the absence of the auto-complete function.

5. Methods

[5.1] In this study, I sought to test Price's fan tag taxonomy (2017) on a different fandom in order to compare our results and to see if I encountered tags that could not be classified using her system. For her study, Price analyzed tags occurring on works tagged Romy, which is a portmanteau of the character names "Rogue" and "Remy LeBeau" (Gambit) from the Marvel Comic Universe and is used to refer to the romantic relationship between those characters. The tag is wrangled under "Remy LeBeau/Rogue" on AO3, which is used interchangeably with Romy in this article. Price notes that she decided to analyze works tagged Romy because it is a relatively small fandom that is easier to investigate than more popular ones and because her experience as a longtime fan of the Marvel Universe and more specifically of the Romy ship would reduce the time needed to research tag meanings and would improve coding accuracy (Price and Robinson 2017). Fandom-specific terminology can be exceedingly difficult to decipher for those who are not also members of a given fandom. For that reason, I decided to analyze tags from works on AO3 that have the Relationship Tag "Sam Carter/Jack O'Neill," indicating the depiction of a romantic relationship between the characters Samantha Carter and Jack O'Neill from the show Stargate SG-1 (1997–2007).

[5.2] Price performed her crawl of works tagged Remy LeBeau/Rogue April 29, 2016 (Price 2017), which would have scraped tags from approximately 285 works, a count estimated for this article by searching that tag in March 2023 and filtering for works updated on or before April 29, 2016. Some works may have been deleted from AO3 between the time when Price scraped data and the time of writing this article, but this estimate is likely very close to the number the search would have returned in April 2016. At the time of the crawl performed for this study, a search for works tagged Sam Carter/Jack O'Neill (aka Sam/Jack) yielded 4,923 results. Due to time constraints and the limitation of performing this study alone, the sample had to be narrowed to a more manageable number, so I scraped tags that occurred on works tagged Sam/Jack within the first fifty pages of results, with crossover fics excluded, and sorted by hits—the number of times the fic has been accessed. I chose to exclude crossovers to avoid encountering tags that fall outside my fandom of expertise. I sorted by hits, reasoning that frequently accessed works may be those which are most discoverable, perhaps indicating that they have been well-tagged by their authors. This choice could have introduced a potential downside by unintentionally favoring works that have been in the archive for a longer period. Newer works may also be well written and/or well tagged, but they have not had time to accrue the thousands of hits that older works have amassed over the eleven years of writings represented in AO3. Still, the first twenty works sampled (representing one page of results on AO3) contained works that were last updated between 2011 and 2021, with eight of those having been last updated since 2018. The third-most-accessed work at the time was completed only three months before the data was scraped, and the work ranked ninth in this sorting was first posted in April 2020 and had last been updated on March 17, 2021––days before this scrape was conducted. Therefore, more recently written works don't seem to have been entirely deprivileged by choosing to sort by hits.

[5.3] I used the BeautifulSoup Python library to write a script that requested the HTML files for the first fifty pages of works listings and parsed those files to extract all tags within the selected sample, as well as each tag's fic title, author username, and AO3-assigned tag class. I then exported that dataset as a comma-separated value (CSV) file in which each row represented a single tag and contained the full text of the tag, the title of the work on which it appears, the author's username, and the tag class as defined by AO3. While the title and author username were not analyzed, they allowed me to sort and re-sort tags as I analyzed, so that I could look at each tag in the context of other tags on the same work. A tag that provides author commentary, for example, might not make sense when separated from its work and viewed in an alphabetized list of tags, but its meaning is clear when viewed in the context in which it appears on its work on AO3. New works are constantly being added to the archive; this data represents the state of the collection as of March 2021.

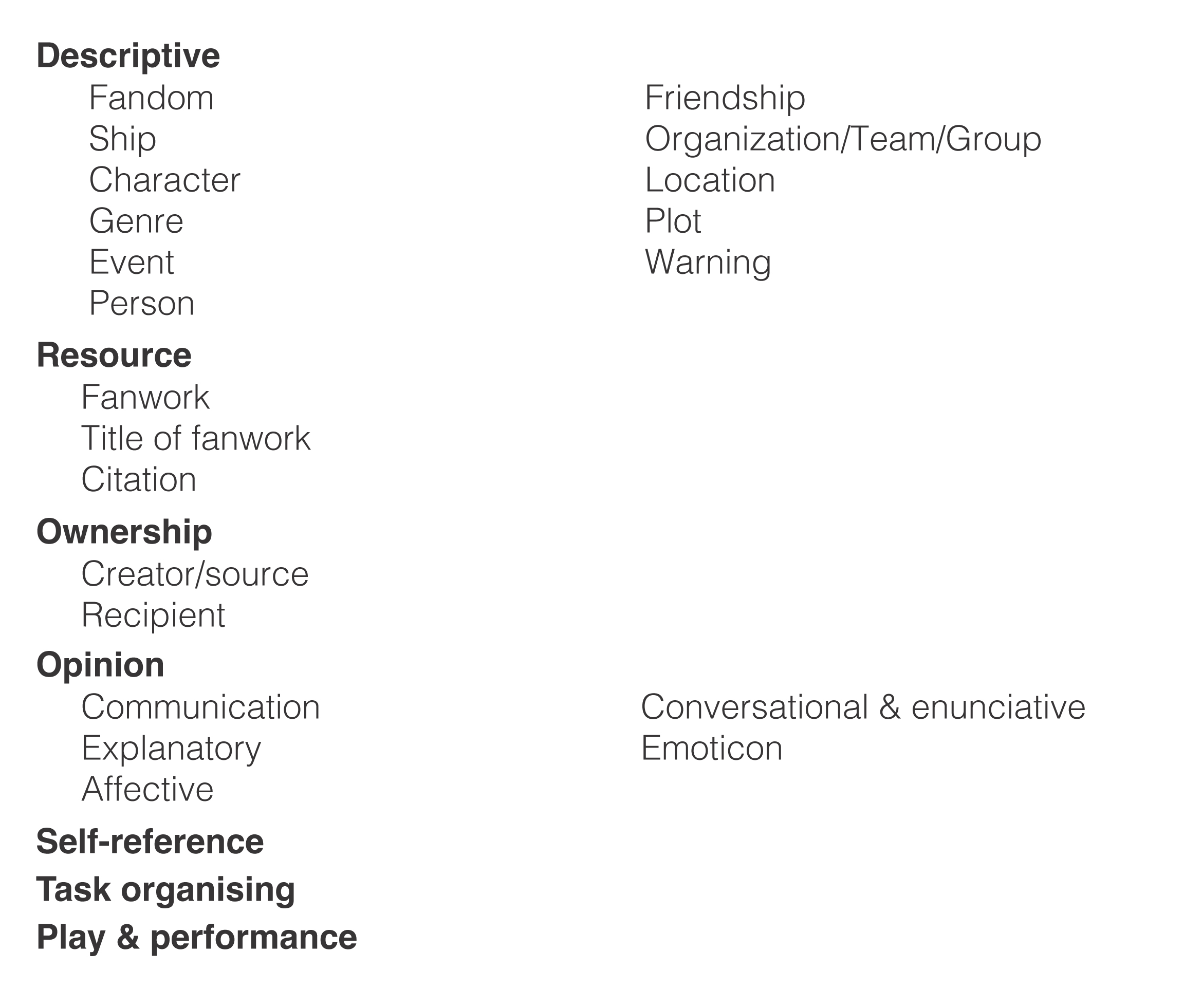

[5.4] I first coded each tag by type and subtype according to Price's fan tag taxonomy (2019). Price's taxonomy expands the types of tags defined by Smith (2007)—descriptive, resource, ownership/source, opinion, self-reference, task organizing, and play and performance—into subtypes that adequately describe the granularity of fan tags she observed on Tumblr, Etsy, and AO3 (Price 2017). She defined an additional eleven subtypes of descriptive tags, three subtypes of resource tags, two subtypes of ownership tags, and five subtypes of opinion tags (figure 2).

Figure 2. Fan tag types and subtypes as identified and organized by Price (2017).

[5.5] The only training available for use of the taxonomy was by way of the examples listed on Price's published taxonomy and reference to the co-occurrence graphs from the same study (2017, 2019). Every effort was made to employ the taxonomy as Price did, but there could be some differences in how she and I categorized similar tags. Initially, I coded only according to the examples listed on the taxonomy, which seemed to lead to inconsistencies with Price's coding. For example, I categorized many tags as Warning because they described explicit sexual content, drug use, or violence. I reasoned that if swearing is categorized as Warning in the taxonomy examples, other content that would be categorized as adult or mature in content rating systems like MPAA would also be categorized as a warning. After further review of Price's co-occurrence graphs, though, I noticed that most tags related to sexual content and other material that would be categorized as being for mature audiences in most rating systems, such as "dom/sub," "drug usage," and "plot what plot/porn," were categorized under Genre rather than Warning (2019). I also considered that tags that might serve as a trigger warning, such as "slavery" or "self-harm," would be categorized as Warning tags, but I saw that similar tags were also categorized as Genre tags on the co-occurrence graphs. On further review, it seemed as though the only tags categorized as Warning in the portion of Price's study conducted on AO3 were the official archive warnings (2019), so I re-coded the tags in my data to better match the examples available. After coding, I examined the relative frequency at which different types and subtypes of tags occurred within the tag set scraped from works tagged Sam Carter/Jack O'Neill and compared those findings with Price's data (2017) in an effort to compare tagging behaviors between the fandoms we studied.

6. Scope and limitations

[6.1] I originally set out to compare the tagging behaviors of two distinct fandoms by applying Price's fan tag coding schema (2017) to a set of tags scraped from a different fandom on AO3, but it soon became evident that more work was necessary to simply develop a taxonomy; therefore, the goal of my research shifted into an exploration of applying Price's schema and analyzing its utility for future panfandom research. Several factors constrained the design of this study, including a limited one-year time frame, working as a solo researcher, and using data from a previous study that could not be manipulated in the same ways mine could.

[6.2] Because of the somewhat limited coding examples available, there will be some differences between my coding and Price's. Additionally, the samples themselves are not entirely comparable––in her study, Price included crossover fics while I did not, and a method of removing all tags from crossover works from her dataset could not be devised within the time frame of the study. Although I compare our tag sets in my findings, the results are not generalizable and should be viewed as an exploration in applying the coding schema rather than an explanation of fan tagging behaviors.

7. Findings and discussion

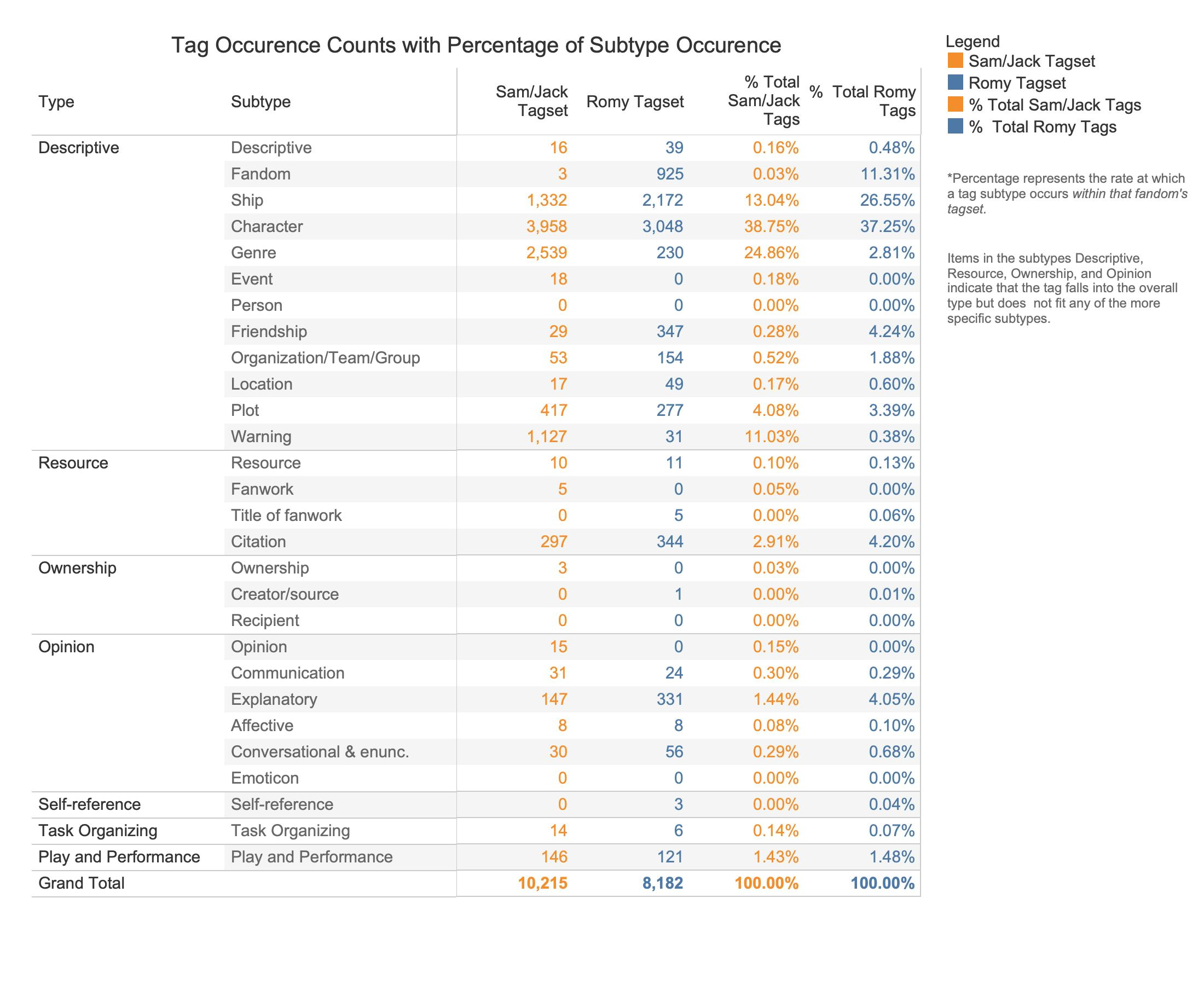

[7.1] The scrape of tags from the works sampled in the Stargate fandom on AO3 produced a dataset of 10,221 tags, with 1,873 distinct tag names. Price's crawl of the Romy tag produced a total of 8,182 individual tags, with a total of 4,368 tag names (2017). The number of times each tag subtype occurred as well as the percentage of tags that count represents within the corresponding tag set can be found in figure 3.

Figure 3. Frequency of tag subtype occurrence in each tag set. Columns "Romy Tag Set" and "% Total Romy Tags" created using data from Price's 2017 study.

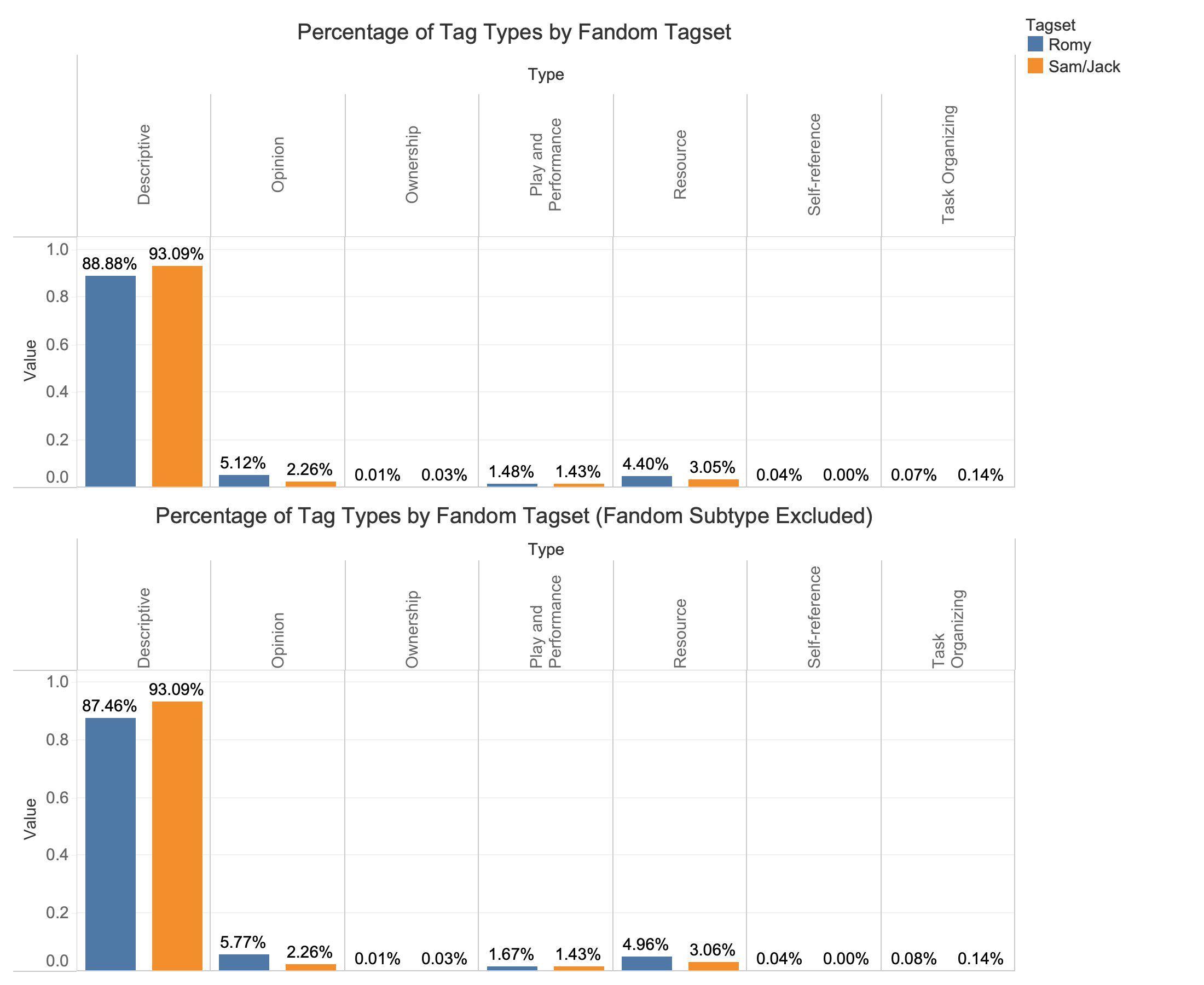

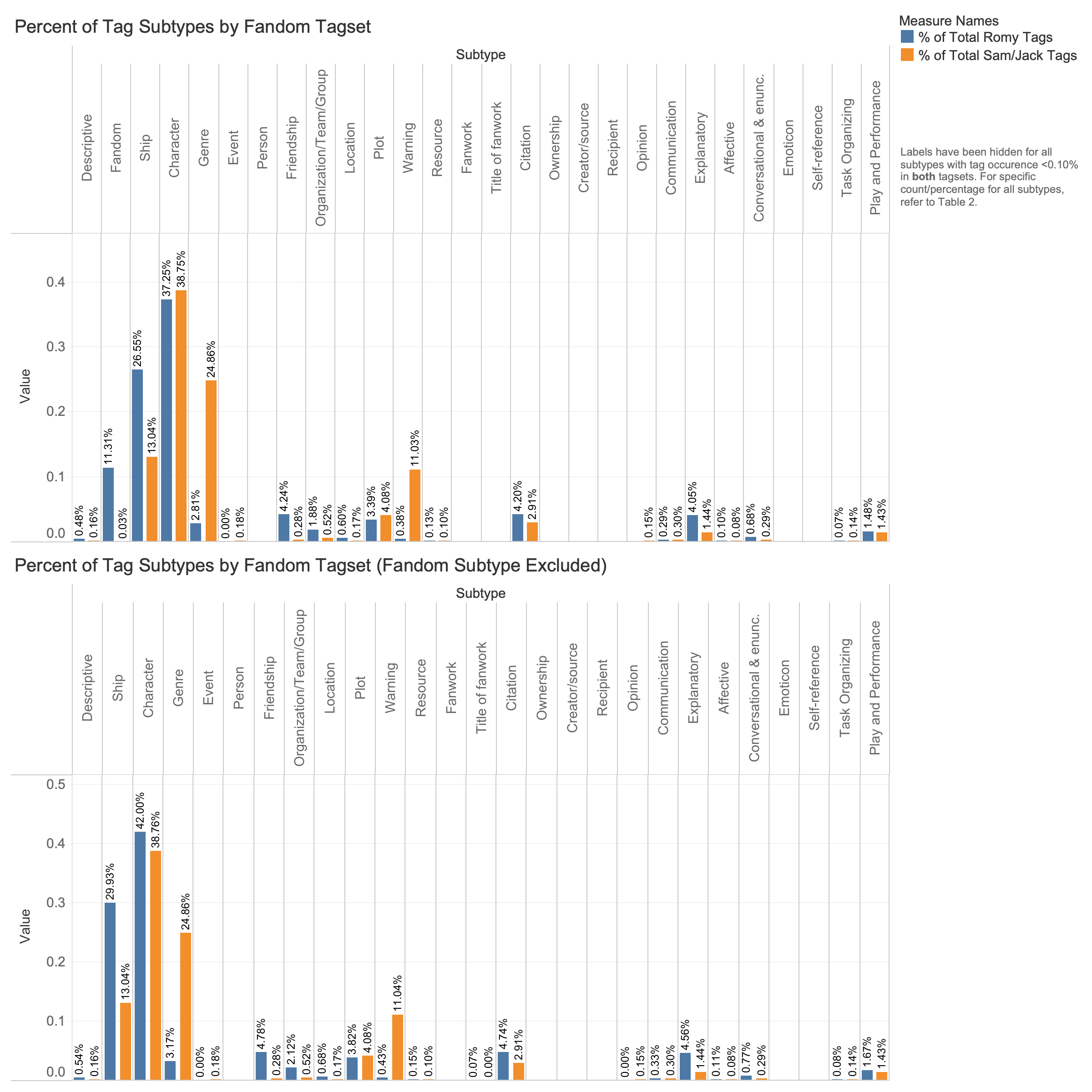

[7.2] The usage by percentage of different tag types among tags on works sampled from the Stargate fandom is shown in figure 4, with Price's data for comparison.

Figure 4. Comparison of tag use frequency between works tagged Romy and works tagged Sam/Jack on AO3. Bars representing the Romy tag set were produced using data from Price's 2017 study.

[7.3] Descriptive tags are used most often in both fandoms by a wide margin. When collecting data, I chose to exclude crossovers so as to narrow the results I pulled to those belonging only to the Stargate fandom. Therefore, I've included two visualizations in figure 4: one showing findings that include all our coded data, and one showing our data with the Fandom subtype excluded. For data from the Sam/Jack set, the frequency of Descriptive tag types remained the same at 93.09 percent after excluding Fandom tags, but for data from the Romy set, the frequency of Descriptive tag use drops slightly, from 88.88 percent to 87.46 percent. Frequency of use for Resource, Opinion, Task Organizing, and Play & Performance tag types also increases negligibly, by 0.56 percent, 0.65 percent, 0.01 percent, and 0.19 percent, respectively. At the tag Type level, the relative frequencies of tag use remain similar, regardless of Fandom exclusion. Descriptive tags are used more in the Sam/Jack dataset than in Romy, and conversely, Resource, Opinion, and Play & Performance tags are used more often among Romy tags than Sam/Jack. Similarly, regardless of Fandom exclusion, tags categorized as Ownership, Self-Reference, and Task Organizing comprise less than 1 percent of tags in either set, even when those three subtypes are combined.

[7.4] As in figure 4, I have included two visualizations in figure 5, with the second showing relative subtype occurrence when the Fandom subtype is excluded. At the subtype level, before excluding Fandom tags, we see that Romy tags are coded as Fandom, Ship, Friendship, Organization/Team/Group, Location, Citation, and Explanatory more often than in the Sam/Jack tag set. Conversely, Character, Genre, Plot, and Warning tags occur more frequently among Sam/Jack tags than Romy. However, when we exclude Fandom tags, the occurrence of Character tags in the Romy dataset relatively increases by a notable 4.75 percent to surpass the occurrence of that tag subtype in the Sam/Jack dataset. At this level, the occurrence of tags coded Descriptive, Event, Person, Location, Resource, Fanwork, Title of Fanwork, Ownership, Creator/Source, Recipient, Opinion, Communication, Affective, Emoticon, Self-Reference, and Task Organizing is so infrequent as to not be visible on visualizations scaled for the size of print on standard paper or most digital devices.

Figure 5. Comparison of tag usage rates at the subtype level. Bars representing the Romy tag set were produced using data from Price's 2017 study.

[7.5] In both fandoms, Character tags appear most often, followed by Ship tags, which makes sense given that every work in this data contains at least one Ship tag––"Remy LeBeau/Rogue" (Romy) or "Samantha Carter/Jack O'Neill" (Sam/Jack). For Romy tags, the inclusion or exclusion of Fandom tags affects the order of the top three most-common tag subtypes. When included, Fandom tags appear as the third-most frequently coded Romy tag subtype. When excluded, Ship and Character subtypes both increase proportionally. Plot can also be seen to increase slightly (by about 0.5 percent), but no other subtypes within the set are notably affected.

[7.6] Genre and Warning tag occurrence stand out most notably to differentiate the Sam/Jack tag set and the Romy tag set with both subtypes coded much more commonly among Sam/Jack tags.

[7.7] While Descriptive tags are the most used tag type in both the Marvel and Stargate fandoms, the most commonly used subtypes of Descriptive tags vary. Character tags comprise a higher percentage of the Romy tag set than the Sam/Jack tag set by 3.24 percent when adjusted to exclude Fandom tags, possibly because there are more distinct, named characters in the Marvel universe than the Stargate universe. While the Stargate franchise has three major shows, a cartoon, a miniseries, and several tie-in books, the Marvel franchise has been publishing comics in a number of distinct series since 1939, had released twenty-three movies by 2021, and had produced eleven television series by 2021. In contrast, each of Stargate's three shows focuses on a team of four to eight main characters, along with a small ensemble of supporting characters and villains.

[7.8] While only a slightly higher usage of Character tags is found in the Romy dataset, the occurrence of Ship tags among the Romy data (29.93 percent) is over twice as high as among Sam/Jack tags (13.04 percent), indicating that more romantic relationships are tagged among Romy works. Consider the fact that the Romy tag set represents approximately 285 works and contains 2,172 Ship tags, while the Sam/Jack tag set represents 1,000 works and contains 1,332 Ship tags. Each work in each dataset contains at least one ship tag—either Romy or Sam/Jack, respectively. Therefore, among the selected Sam/Jack fics, additional romantic pairings appear 332 times, while among Romy fics, additional romantic pairings appear 1,887 times. The existence of more total characters in the MCU, as well as relationships from fandoms outside of MCU, which could not readily be excluded from Price's data, likely accounts for some of this discrepancy. Each work contains at least one Ship tag, but what percentage of works in each set contain multiple Ship tags? While that unfortunately cannot be deduced from the current data because of the way it was collected, it could be an interesting follow up for future research.

[7.9] A relationship categorization problem emerged while coding Sam/Jack data according to this taxonomy, which includes definitions for Ship to indicate romantic relationships and Friendship to indicate friendships between characters but does not include a category for nonromantic familial relationships. One work in the Sam/Jack sample includes the tags "Jacob Carter/Mark Carter (SG-1)" and "Jacob Carter/Sam Carter," both of which describe the relationship between a parent and child. For this study, they were included in the "Friendship" subtype, but I argue it does not accurately describe that relationship type. Only these two tags presented this problem among the tags collected for this study, but for fandoms in which source media centers around family relationships, like Modern Family, it could pose a larger problem.

[7.10] I predict that the wide variety of comics, movies, and television series in the Marvel universe also partially accounts for the higher use of Fandom tags in Price's findings (2019) when compared to mine. Writers in the Stargate fandom hardly use Fandom tags, but they are the third most commonly used tag subtype in the Marvel fandom. A work tagged Romy might have Fandom tags for Wolverine (Movies), Wolverine and the X-Men—All Media Types, X-Men: The Animated Series, or many other media works that are part of the broader Marvel fandom. In contrast, the Stargate TV universe has only five fandom tags on AO3—Stargate SG-1, Stargate Atlantis, Stargate Universe, Stargate Infinity, and Stargate—All Media Types. The method by which I filtered works for my study before collecting tags also partially accounts for the lower occurrence of Fandom tags in my study. Because I excluded crossover works, tags from a completely different fandom, like Harry Potter, would not have appeared on works in my data. Price did include crossovers, so fandom tags outside of the Marvel Comic Universe appeared in her findings.

[7.11] In Stargate fandom, Genre and Plot tags represent a higher percentage of tags than in Marvel fandom. It could be that there are a similar number of distinct Genre and Story Element tags in Marvel fandom and that they simply represent a lower percentage because of the greater number of characters, romantic relationships, and friendships as compared to Stargate fandom. Though possible, it seems unlikely that there would be fewer story elements or genres represented among the works in her data. In fact, Price's scrape of Romy works produced twice as many distinct tag names despite the scrape in this study collecting 2,000 more total tags. This difference may have been heavily influenced by difficulty that arose while trying to decide which tags belonged to the Genre subtype.

[7.12] In the coding observed from Price's study (2017), the Genre subtype includes expected tags like Humor, Angst, and Romance, but it also includes tags like Voyeurism. As previously mentioned, I tried to code as closely as possible to the Price's coding decisions based on examples I could see in her work (2019), and Voyeurism is clearly categorized as a Genre tag in one of her co-occurrence graphs. I would have coded Voyeurism and similar tags as the Plot subtype because I see that as descriptive of a story element in a work that might fall into the broader Genre of Romance or Smut rather than descriptive of an entire category of works. Even when trying to model coding after another person's examples, it is an inherently subjective process. Tags may fit into multiple categories, and one coder's judgment call may vary from another coder's choice; however, a more robust dictionary for training would likely improve agreement between coders.

[7.13] Authors in both fandoms seem to express more opinions that explain plot points than opinions that convey their feelings. In contrast, Gyhagen found that AO3 bookmarks contain affective communication more prominently than other types of communication (2022). A study comparing bookmark tags and author tags from the same works could reveal interesting variations in the behaviors of readers and writers.

[7.14] There is a slightly higher usage of Play & Performance tags on Romy works (1.67 percent) than on Sam/Jack works (1.43 percent) in these samples. These tags indicate events and competitions like samjackshipmas2020, where authors celebrate Christmas by writing works that revolve around Sam and Jack celebrating the holiday together; icalledhimsir, a competition challenging authors to write fics where Sam calls Jack "sir" in an intimate context; and NaNoWriMo, indicating the fan wrote their fic as a part of National Novel Writing Month. They are therefore a tag type through which we can compare the degree of community-building activity present in each fandom. Though it would make sense for there to be more events and competitions generated among members of a fandom consisting of millions of comic book readers and moviegoers around the world than the fandom of a cult hit sci-fi show that last produced new source content nearly twenty years ago, the tag data indicate a similar degree of communal activity within each fandom. The tag samjackshipmas2020 indicates that there was some degree of community engagement happening in December 2020. Although the source content of Stargate SG-1 is much older, with no recent releases to spark increased fan activity, fan activity may have seen a spike during the pandemic, as people increasingly sought ways to connect with one another through online events, safe from disease transmission.

[7.15] In both fandoms, there is little use of Ownership, Self-Reference, or Task-Organizing tags. Price's taxonomy of fan tags was developed for use on multiple sites (Tumblr, AO3, and Etsy), and the lack of representation for the Ownership and Task-Organizing subtypes on AO3 is likely because there are separate mechanisms on AO3 to communicate those ideas.

8. Conclusions

[8.1] Authors across both fandoms on AO3 most commonly use tags to describe their story, express their opinion, cite resources, and indicate the work's inclusion in a competition, event, or exchange. Broadly speaking, tagging behaviors at the level of tag Type appear similar across fandoms. Based on the results of this study, it seems that Price's taxonomy translates well for use in a different fandom in the sense that nearly all tags encountered in the new fandom fit into a type/subtype defined by Price, with a few exceptions. While the use of tags by subtype varies between the Stargate fandom and the previously investigated Marvel fandom (Price 2019), the ratios of tags by broader type are similar across the fandoms, except in the subtypes of Genre and Warning.

[8.2] Throughout the process of this study, the practical application of Price's taxonomy (2019) in a way that would allow comparison of our results proved difficult. Without more coding examples and deeper explanations of the difference between categories like Genre, Plot, and Warning, coders will almost certainly apply subtypes differently. For the sake of developing a taxonomy for pan-fandom research, it would be helpful to create a more comprehensive guide to coding fan tags so that varying coder judgment will be less likely to impact findings. As previously stated, the language used in different fandoms can be confoundingly difficult to interpret by someone unfamiliar with the work around which the fandom is based. Attempts to compare fan behaviors among multiple fandoms could therefore be hampered by the lack of a standard system to code tags. Inducing a new coding schema every time can work for isolated studies, but for comparable inter-study data, researchers need a standard taxonomy and coding dictionary.

[8.3] Price's taxonomy (2019) worked to describe almost all of the tags found in this study, but one type of character relationship—members of the same family—did not have a category that fit it well. Those relationships would not be a Ship, which describes romantic relationships between characters, but they are also different from Friendship. There may be no need for a category of tags describing family relationships in works filtered by Romy in Marvel fandom, but there are several relationships tagged in Stargate fandom that need that distinction. A Family subtype of Descriptive tag should be added to the taxonomy for use across more fandoms.

[8.4] Regardless of the question of intercoder reliability, both studies clearly indicate that fan writers are more deeply descriptive of their works than current library discovery systems allow. Significant overlap of Genre/Story Element tags appearing in both studies might indicate a high prevalence of new ways that writers think of categorizing their works for readers to find. While these categories may be new, their existence in literature is certainly not. In fact, fan fiction readers have expressed frustration with being unable to search library databases for exactly what they want to read––in contrast with AO3's search and filtering system, which they feel to be second nature (Miller 2022). Today's readers might be more able to find literature that appeals to them if these new categories were applied to the traditionally published works that a user would find in libraries and bookstores, since popular tags like Angst, Fluff, Family, Hurt/Comfort, Relationship(s), and Mental Health Issues can describe works of commercial literature as easily as they do fan fiction.

[8.5] In a broader fan studies context, it is important to study the use of tags by authors and readers of fan fiction in order to understand user needs when designing fan fiction repositories, make sense of the history of fan descriptions of their work (Johnson 2014), and examine the evolution of tag use over time as a way to track the evolution of fandom and fan writing. Fan archives, particularly digital ones, are inherently ephemeral and vulnerable to circumstances that can cause them to vanish irrecoverably, as many indeed have (Versaphile 2011), and fan tags should be studied, understood as essential parts of their respective fan works, and accounted for in discussions of fan work preservation. For all fan studies researchers, fan tags can reveal practices of fan writers, their assumptions about the world, their thoughts about their work, and their creative processes. Developing a taxonomy with which to compare different fandoms may make it easier to see similarities and differences among the many fannish subcultures that comprise the subject of the emerging field of fandom studies.

9. Recommendations for future work

[9.1] As an exploration in the utility of Price's fan tag schema (2017) for panfandom use, this study revealed avenues of future research that would be beneficial. I would recommend further studies that develop the coding schema by (1) collecting data from multiple fandoms in one study to be categorized by a single team of coders, (2) testing what effect, if any, the inclusion/exclusion of crossovers has on the results of analyzing a tag set, and (3) producing a more explicit coding dictionary. These studies could help show whether there are noticeable differences in the types of tags used in each fandom or whether the differences in Price's coding and mine greatly impacted the comparison in this study. Additionally, understanding of the use of fan tags on AO3 would be improved by a study examining the combined author tags and bookmark tags assigned to the same works and improved statistical analysis on tag co-occurrence. Finally, further research should look beyond informants from fan fiction communities to see if the descriptors that have arisen from the folksonomy of fan tags on AO3 also makes sense to readers who have never tried to find fan fiction. If so, libraries may be wise to take the lesson from fan archivists and describe the collections more thoroughly so they can connect more readers with the books that are right for them.

10. Acknowledgments

[10.1] I thank Ludi Price for graciously sharing her data with me in order to conduct this study; Melanie Feinberg and Asye Gursoy for their guidance and feedback; and Amy Hill and Rusty Shackleford for their editing help.