1. Devoted idol fans dominating Chinese fandom

[1.1] The highly organized and coordinated promotional actions of Chinese idol fan communities have generated substantial profits for the Chinese entertainment industry and shaped the cultural landscape of Chinese fandom. Beyond the direct financial contributions of crowdfunding and excessive consumption, fan communities also routinely engage in data generation labor on social media platforms, such as Weibo (Yin 2020; Zhang and Negus 2020). The construction of the meaning of "idol fan" within this specific neoliberal context has been achieved through the cultivation of fan communities as devoted and profitable "fansumers," a term that combines "fan" and "consumer," and the capitalization of their digital practices (Yin 2021).

[1.2] Similar dynamics are at play in the current trend of CP fans (coupling or character pairing fans) who obsess over perceived romantic relationships between two male celebrities. As boys' love becomes increasingly popular in mainland China (Ng and Li 2020; Lavin, Yang, and Zhao 2017), the idol industry and platforms are actively targeting potential CP fans to increase internet traffic and capitalize on the passion of their fan base (Y. Zhang, Huang, and Li 2023). To avoid backlash from nonshipping fans who may accuse them of favoring one idol over the other, CP fans are encouraged to promote both idols with equal financial support and data contribution, as described in the above promotional actions for the perceived romantic pairing. Due to low queer acceptance in mainstream culture and ethical concerns surrounding real-person slash fiction, CP fan communities tend to "keep their fandom within the circle" to protect the reputation of both idols (Zhang 2020). They voluntarily shoulder the responsibility of promoting idols, which renders them potential fansumers with high profitability (Guo 2022).

2. Self-centered shipper communities being marginalized

[2.1] Compared with lucrative promotional actions, secondary creations and other noncommercial fannish activities are often marginalized in the Chinese idol industry (Zheng 2019). While this divide between fans who concentrate on different fannish practices is common in fan communities, the tension is particularly intense between the mainstream CP fans who promote idols responsibly and the marginalized ones who focus on seeking pleasure by producing real-person slash.

[2.2] In this article, I shed light on marginalized and unrecognized CP fans, who refer to themselves as keyao ji or shippers, and their "nomadic queer tactics" against the capitalization and censorship of boys' love (Wang and Tan 2023). Originally intended as a derogatory term, keyao ji has been embraced by those who participate in shipping practices to poke fun at themselves. Within the fandom, terms like yao (drug) or tang (candy) are used to refer to any sign of intimacy between the characters that fans find pleasing. The term ji (chicken) is a metaphor for a fan who is so excited by these moments that they scream in delight. Many shippers gather on a subreddit-like discussion group on Douban, where the group members humorously refer to themselves as changmei (female factory workers) or caomei (berries) as they sound similar in Chinese. Their playful nicknames highlight the perceived class divide between wealthy idols and grassroots netizens. Unlike mainstream CP fans on Weibo, who consider it their responsibility to promote idols, shippers prioritize the pursuit of pleasure through their shipping practices over supporting, promoting, or protecting idols. Instead, they denounce the homogeneous and unprofessional male idols for their queerbaiting and exploitation of fans. This critical stance toward idols and fansumer behavior sets them apart from mainstream idol fan communities and reflects the discontent of grassroots netizens with the dearth of artistic quality and diversity in the current idol industry.

[2.3] I focus on Puppy Dreamworks, a shipper community on Douban dedicated to shipping two Chinese male idols, Rainco and Joseph (R&J). The majority of Berries, the community members, learned about the two idols from a well-received web drama in which the characters they played were suspected to be same-sex lovers. Initially, Berries playfully joked about R&J's offstage romance, but they became convinced that the two stars were secretly in love as they discovered more about their real lives. According to my seven-month participant observation, this group exemplified the most notable shipper qualities, such as free shipping with the least economic input and not empathizing with idols. Berries claimed that Chinese male idols could gain huge profits effortlessly by peddling fake public personae and queerbaiting to exploit female fans. Consequently, fansumer practices such as calling on members to fund idols and expressing love for the two idols rather than their relationship were strictly prohibited in Puppy Dreamworks. The most famous slogan of Puppy Dreamworks, "Treat male idols as toys," disrupted existing norms of the Chinese fandom culture and reflected the shippers' resistance at the grassroots level. Such a way of consuming idols was precisely a protest against the disqualification of idols, the industry's exploitation of fans, and the restriction of real-person slash works. Shipper communities have thus attracted many female fans who enjoy shipping male idols but dislike the strict rules of mainstream idol fandoms. Liberating themselves from digital labor and other promotional duties, they concentrate on crafting their wild shipping dreams in this covert community.

3. Creating diverse characterizations for shipping

[3.1] Growing tired of idolizing male stars as flawless gods dependent on the tribute of their fans, shippers like Berries were passionate about deglamorizing celebrities. By highlighting the idols' underappreciated traits in slash creations, particularly in their characterizations, Berries aimed to heighten the dramatic and sexual tension between the two idols. One of the most popular and controversial characterizations used by Berries was Dog/Lady. In this portrayal, Dog (Rainco) is a flirtatious straight man who accidentally falls in love with Lady (Joseph), a feminine gay man. Berries developed this characterization based on Rainco's hookup scandals and Joseph's femininity, which outsiders saw as damaging to the reputations of both male idols. In response, Berries advocated for sexual liberty and argued that these queer traits were not shameful but appealing. The neologisms of Dog/Lady were consistently employed in Puppy Dreamworks, to signify R&J as both fan fiction characters and real-life celebrities, indicating the entanglement of fictionality and reality in Chinese real-person slash fandoms (Guo 2022).

[3.2] Based on the Dog/Lady and other characterizations, Berries freely weaved shipping discourses into their community. Disseminated in Puppy Dreamworks as playful gossip and slash pieces, these narratives deconstructed the ideal images that were cocreated by R&J's devoted fans (Yan and Yang 2021). Meanwhile, these characterizations of R&J invited raging assaults from fans of the two idols, including CP fans who promote and ship both idols. For these CP fans, shipping fantasies should be regulated to show proper respect for idols and avoid harassment from other fans. Therefore, shippers like Berries were criticized for using offensive characterizations and violating the fandom culture norms of protecting and promoting idols. The contradictory views regarding characterizations highlight the essential difference between the rival communities: shippers, as fans of the romantic and sexual relationship between idols, are committed to wild fantasies, whereas mainstream CP fans adore two idols with intimacy and are more concerned about the careers and public images of the celebrities.

4. Extracting candies to (re)construct a canon

[4.1] The Chinese government's ambiguous and inconsistent stances on LGBT content often lead to the self-censorship of celebrities and entertainment industry practitioners, which ironically fosters queer fantasies and conspiracy theories about celebrities' sexual identities. Therefore, the candies denoting romantic associations are believed to be hidden and require intentional archeological mining and candy extraction. The former refers to validating fantasies with past real-life evidence, often followed by extracting candies, which involves discussing and analyzing the evidence. Berries roam around different social media platforms, not only tracking R&J's social footprints in real time but also trying to unearth any potential intimate connections revealed by their past activities. In addition to discussing these two idols, they also gossip about mutual acquaintances of the idol couple who might provide insight into their relationship from different perspectives. After mining these primary materials, Berries creatively associate, aggregate, and interpret the related information to obtain candies. The credibility of each candy depends on factual evidence and the logic of the analysis. To further evaluate the candies' persuasiveness, Berries often use an external review strategy by inviting nonshippers to assess whether they are sweet (convincing), as outsiders are deemed more objective. While R&J's fansumers on Weibo also engage in similar candy extraction activities, Berries consider themselves more stringent in the rating process than those mainstream CP fans because Berries consistently examine and debate which candies are too hard to chew (far-fetched).

[4.2] All the candies extracted were gathered as building blocks to construct a canon history of R&J, which is the perceived authentic relationship between the two idols. In fandom, canon is commonly understood as original sources considered authoritative by fan communities. The analysis of mining and extraction reveals how shipping practices contribute to the discursive formation of an imagined romantic relationship, which was cocreated by idols and shippers. The candies extracted are believed to be less performative than blatant intimacy, which could be suspected of serving promotional purposes. However, the extraction process inevitably involves subjective interpretation and imagination, which could compromise the authenticity of the evidence. Despite this, some candies were convincing enough for Berries to build a solid foundation of a canon history of the idols.

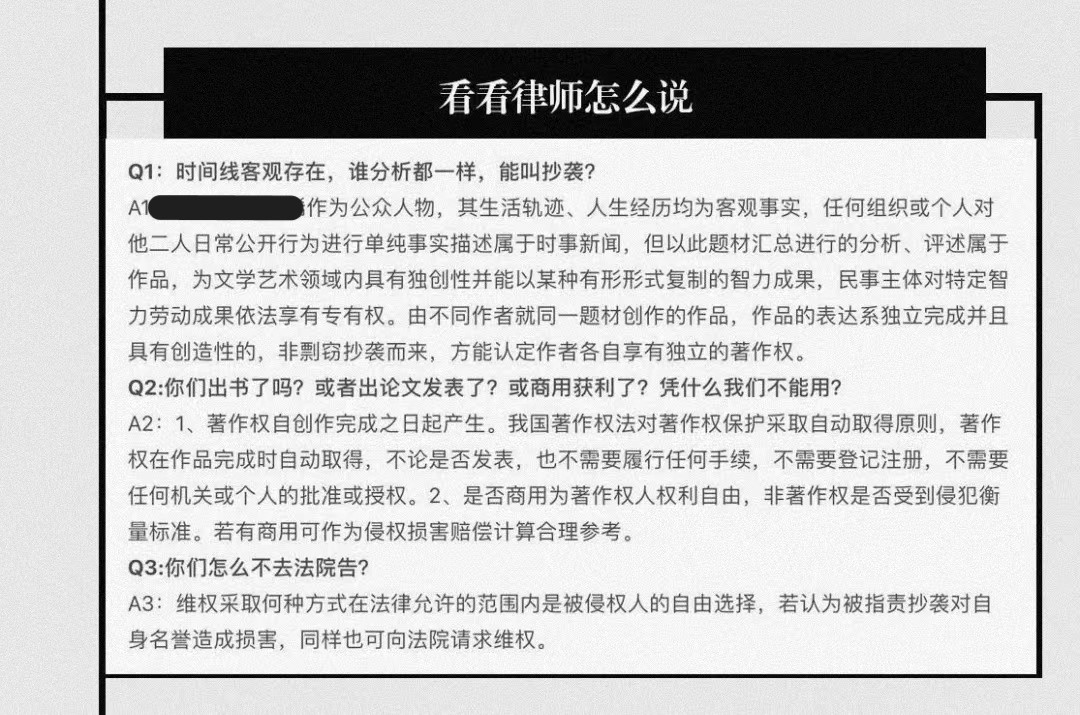

[4.3] Apart from arguing for the creative freedom to develop celebrity characterizations, Berries also strive to claim their copyright over the candies they have extracted, illustrated by the following incident. In 2019 and 2021, Rainco and Joseph posted two videos on their official Weibo accounts, each on different topics that initially seemed unrelated. After repeated viewings, close analysis, and heated discussion of the possible shooting locations and camera angles, Berries came to an agreement that Rainco and Joseph had gone to see fireflies together when they shot the web drama. Although the celebrities publicly posted the videos, this thrilling candy was considered knowledge derived from Berries' collective intelligence. The intentional process of extracting this information established these candies as arguable slash products of Puppy Dreamworks. As a result, when they noticed that the rival CP fan community copied their analysis of watching fireflies together and other candies, outraged Berry representatives opened a Weibo account to publish a marked post showing the evidence they had gathered and accusing the CP fans of plagiarism. In a Weibo post (figure 1), a lawyer's words were quoted as the legal basis for the argument: "Celebrities' public life trajectory and experiences are objective facts, but the analysis and comments based on the amalgamation of selected materials are original literary and artistic products protected by Copyright Law of PRC." Despite this, CP fans refuted the accusation of plagiarism, claiming that Berries were being narcissistic and that all candies were created by and belonged only to the idols. Without receiving any apologies but facing more harassment, Berries ridiculed these Weibo CP fans as shameless "Copy Fans." The dispute between Berries and CP fans over the ownership of the candies as creative slash products highlights the unique copyright matters in shipper fandoms.

Figure 1. Screenshot of a Weibo post quoting a lawyer's words.

5. Transmedia storytelling fan art based on the canon

[5.1] Based on uncovered romantic canon, Berries were highly motivated to produce transmedia fan art with copious characterizations and candies. They appropriated canon episodes to create slash products in various forms, including literature, paintings, photographs, songs, edited videos, and tangible products. The release of slash products on music, video, and other social media platforms served as not only gifts for existing Berries but also invitations to potential shippers. By clicking hyperlinks of the fan art posted in the Douban discussion group Puppy Dreamworks, Berries could conveniently navigate from a niche forum to multiple mainstream media platforms, where they inevitably encountered rival communities such as CP fans and nonshipping fans of the two idols. Despite boycotts and reports from their rival fan groups, Berries proudly labeled their fan art with the Puppy Dreamworks logo to proclaim that "Berries created these high-quality slash products."

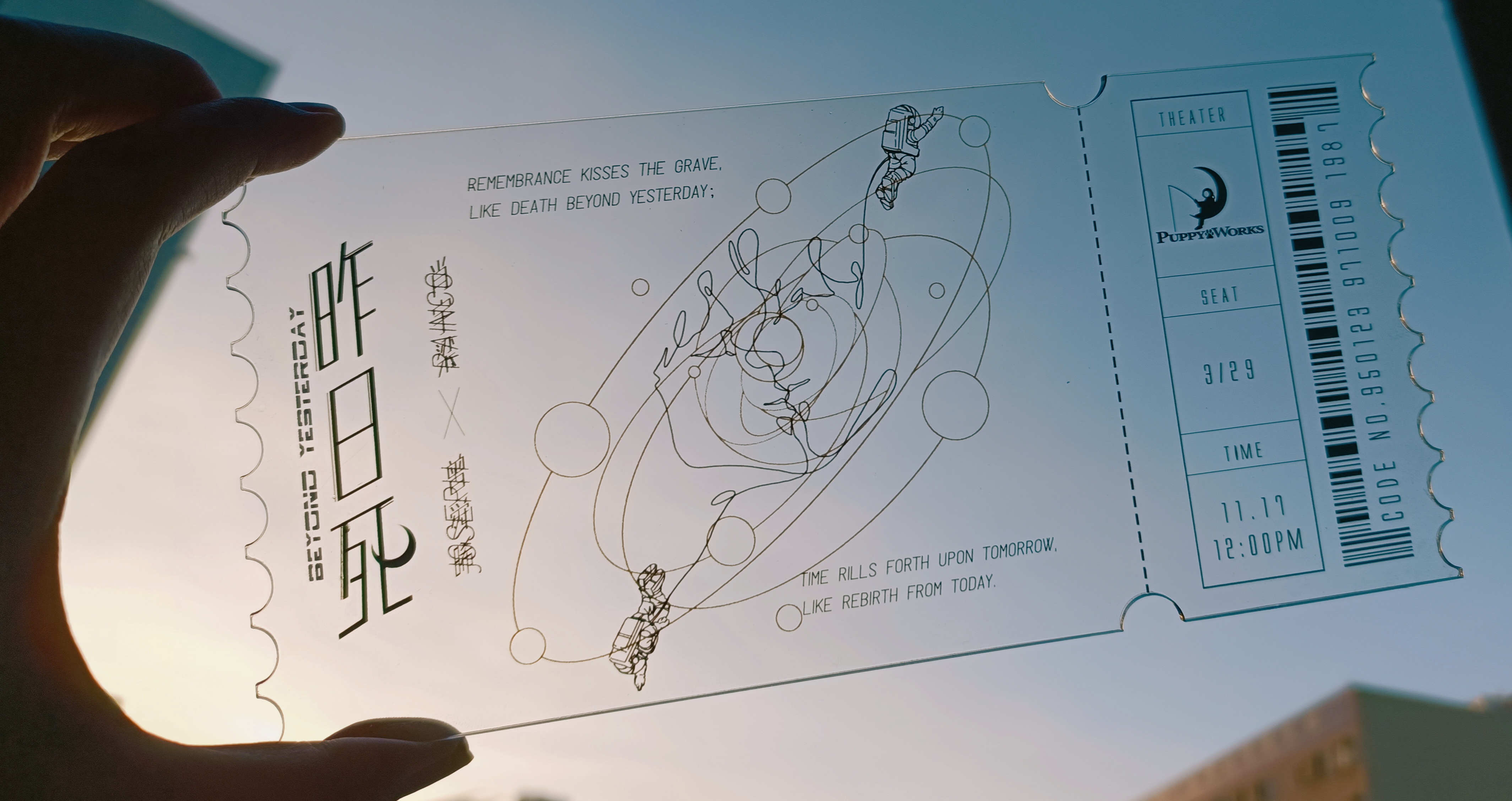

[5.2] The series of slash products produced in Puppy Dreamworks, entitled "Beyond Yesterday," exemplifies the transmedia storytelling of fan art. Inspired by both idols' shared dream to be astronauts, the original fan fiction novel "Beyond Yesterday" depicts a poignant story set in outer space. Moved by this novel, a Berry created a glorious film poster for it (figure 2). Then a team of four Berries adapted this novel into a short but impressive film by cleverly editing and piecing together previous videos of the two idols and scenes from films like Interstellar and The Wandering Earth. Imitating the American film studio DreamWorks Animation, the team created an animated 3D logo of Puppy Dreamworks as the film's opening, which was later used in other videos by Berries. The directorial team carefully weaved as many candies as possible into this film. For example, Rainco and Joseph shot a series of photos for the magazine Madame Figaro Mode in which they labeled themselves as partners, suggesting an intimate relationship. The queer connotation of the term "partner" led the Berry directors to include it as an episode in their film. "Berry," the third character in this film, also appeared as a robot who witnessed their love in outer space, echoing Berries' real-life shipping practices. The success of this film further motivated other Berries to write an opening song for this film and to design and produce acrylic film tickets as gifts (figure 3). After a Berry released an invitation letter to the film premiere as fan art, other Berries posted fictional reports of the film premiere scene where they saw Rainco and Joseph attend as leading actors. By replying to fictional reports, Berries shared vivid and touching details of their imagined memories of the event, such as "I was also deeply touched by Rainco and Joseph's kiss in the scene! The white suits they were wearing made them look like grooms at the wedding. Excited to witness their collaboration again!" In this way, Puppy Dreamworks manufactured all these sweet dreams embodied as transmedia fan art, providing Berries with a rich and immersive storytelling experience.

Figure 2. Fan-created film poster for a work of fan fiction.

Figure 3. Fan-created acrylic film ticket for the fan-made film of a work of fan fiction. Photo taken by the author.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] By articulating indigenous concepts and shipping practices, I have introduced shippers as an underrepresented type of fan in the broader sense. Unlike the mainstream fansumers devoted to idols, shippers focus on the pleasure of secondary creation and rebellion against the Chinese idol fandom norms by advocating for freedom of speech and refusing to support idols financially. Addressing the cultural specificities of a shipper community, Puppy Dreamworks, I offer a contextual understanding of these female fans. Obsessed with the construction of queer fantasies without being devoted to idols, these shippers were marginalized by both the mainstream culture value system and the hegemonic Chinese fandom.

7. References

Guo, Qiuyan. 2022. "Fiction and Reality Entangled: Chinese 'Coupling' (CP) Fans Pairing Male Celebrities for Pleasure, Comfort, and Responsibility." Celebrity Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2022.2105165.

Lavin, Maud, Ling Yang, and Jing Jamie Zhao. 2017. Boys' Love, Cosplay, and Androgynous Idols: Queer Fan Cultures in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Ng, Eve, and Xiaomeng Li. 2020. "A Queer 'Socialist Brotherhood': Guardian Web Series, Boys' Love Fandom, and the Chinese State." Feminist Media Studies 20 (4): 479–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1754627.

Wang, Yiming, and Jia Tan. 2023. "Participatory Censorship and Digital Queer Fandom: The Commercialization of Boys' Love Culture in China." International Journal of Communication 17:2554–72. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/19802.

Yan, Qing, and Fangkai Yang. 2020. "From Parasocial to Parakin: Co-Creating Idols on Social Media." New Media and Society 23 (9): 2593–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820933313.

Yin, Yiyi. 2020. "An Emergent Algorithmic Culture: The Data-Ization of Online Fandom in China." International Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (4): 475–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920908269.

Yin, Yiyi. 2021. "'My Baby Should Feel No Wronged!': Digital Fandoms and Emotional Capitalism in China." Global Media and China 6 (4): 460–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/20594364211041681.

Zhang, Ming. 2020. "'Keep the Fantasy within a Circle': Kai Wang and the Paradoxical Practices of Chinese Real Person Slash Fans." Celebrity Studies 0 (0): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2020.1765074.

Zhang, Qian, and Keith Negus. 2020. "East Asian Pop Music Idol Production and the Emergence of Data Fandom in China." International Journal of Cultural Studies 23 (4): 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877920904064.

Zhang, Yiyan, Shengchun Huang, and Tong Li. 2023. "'Push-and-Pull' for Visibility: How Do Fans as Users Negotiate over Algorithms with Chinese Digital Platforms?" Information, Communication and Society 26 (2): 321–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2161829.

Zheng, Xiqing. 2019. "Survival and Migration Patterns of Chinese Online Media Fandoms." Transformative Works and Cultures, no. 30. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2019.1805.