1. Introduction

[1.1] In China, celebrity fandoms have adopted a strategy of appropriating political issues to eliminate negative comments about celebrities. This strategy empowers them to seek social influence and apply agenda-setting to their advantage and, in turn, acquaints Chinese celebrity fandoms with politics and impacts their political expression. A typical example is the 227 Movement, which illustrates how fans have attempted to win a fan war by bringing up a variety of social issues. The following three types of fans play a significant role in the movement, and they are very frequent participants in other fan wars as well: (1) the "one and only" fans, identified as Wei Fans (WFs); (2) fans who pair two celebrities, identified as Couple Fans (CPFs); and (3) media fans. The purpose of the research is to examine, using the 227 Movement as an example, how celebrity fandom transforms from an "apolitical online sanctuary" (Yang 2017, 380) into political communities that explore social influence and navigate agenda-setting. I examine tweets posted on Weibo, a Chinese social media platform widely used by fans, to gain a deeper understanding of how traditional Chinese social structures, long-standing perceptions of public and private, and government regulation of cyberspace have impacted Chinese celebrity fans' discursive practices, by presenting (1) a historical analysis of the differential mode of association and the development of Chinese celebrity fandoms; (2) a study of fans' tweets regarding the 227 Movement; and (3) a discussion of how these factors interact with the 227 Movement. Specifically, I attempt to answer the following questions: First, what topics were discussed in discursive practices during the 227 Movement? Second, what political issues have been appropriated by fans as strategies to win the fan war and mobilize the community?

2. Chaxugeju, political indifference, and Chinese fandom

[2.1] As a subculture, fandom serves as an emotional outlet for young people who seek an unconventional lifestyle. This must be examined and analyzed through the lens of social structures, traditions, and norms constructed by the majority, where, under the context of Chinese society and history, Fei Xiaotong's Chaxugeju is a fundamental theory to apply. Chaxugeju was first introduced by Fei Xiaotong as the differential mode of association to summarize the social structure and the mode of association (or, as some scholars interpret, personal networks or social networks) (Yan 2006, 203) in traditional Chinese society. Although Fei's analysis was based on agrarian society before the late Qing Dynasty, Chaxugeju has had a lasting effect on modern society in China (Feng 2007). Fei defines the Chinese pattern as ripples, demonstrating that Chaxugeju possesses a self-centered quality: "In these elastic networks that make up Chinese society, there is always a self at the center of each web. Nevertheless, this notion of the self amounts to egocentrism, not individualism" (1992, 67). The self does not own an independent personality. Instead, the self is wrapped up with renlun (human relationships), a Confucian school concept. Bu Changli summarizes renlun: "As long as one is alive, he/she should obey his/her father at home, obey her husband when married, and obey his/her emperor at the court, always ignoring him/herself" (2003, 22). Thus, the self-centered quality is to grant families and clans top priority. Notably, such obedience does not mean absolute loyalty to fathers, husbands, and emperors but rather consistency with his/her different social roles which requires that "everyone should stay in his(/her) place" (Fei 1992, 65). Sun Liping argues the self is a "family oriented self" with a fluidity to set boundaries between the internal and external, as space between two near concentric circles of the ripples is internal for the larger one and external for the smaller (1996, 20). Exclusiveness and closeness are the characteristics of interpersonal relationships built upon Chaxugeju (Bu 2003). The closer to the family-oriented self (i.e., the stronger kinship), the easier it is for one to accept and cooperate, and vice versa. Built upon "lun is order based on classifications" (Fei 1992, 66), the very core of the Confucian ethics explained as "toward the intimate, there is only intimacy; toward the respected, only respect; toward superiors, only deference; between men and women, only differences; these are things that people cannot alter" (Fei 1992, 66). As Yan Yunxiang concludes, it "negates the possibility of equality in personality, derecognizes the balance between rights and duties, and eventually contributes to the cha and xu [i.e., hierarchy] in personalization" (2006, 212).

[2.2] From fathers–sons to monarchy, "the path runs from the self to the family, from the family to the state, and from the state to the whole world (tianxia)" (Fei 1992, 66). The public sphere, on account of Chaxugeju, requires an Almighty to unify the society, define social norms, and produce a top-down system. Each association/social network should form according to the social networks centralized around the Almighty, which thus lays the foundation for order and social structure (Xuan 2015). The idea of the Almighty should not be represented by a certain ruler but by the politics on how to achieve gong, or the public, as "When the Grand course was pursued, a public and common spirit ruled all under the sky all (da dao zhi xing ye, tian xia wei gong)" (Confucius 2008, 23). Therefore, alongside Chinese history, ancient philosophers and political ideologists extol the greatness of the public and grant it supremacy in political ontology and criticize the private by encouraging its elimination. That is, it ought to be stifled, all the thinkings and desires related to the self, as categorized within the private realm (Liu 2003a). In other words, the public establishes its dominance not by publicizing its advantages but by denying the private. Consequently, citizens fight against thoughts related to the self while living in the private spheres, where they have to fly their own kites. Particularly, it is most likely for one to suffer from a loss of legitimacy for their political participation, including political expression, once politically labeled as seeking private benefits (Liu 2003b). The principle of political participation for ordinary people is to "avoid trouble" (Lao 1980, 14), suggesting the intention to discuss politics is curbed, when caring for the private spheres is antagonistic against the public sphere, leading to a lack of political expressions among the majority of Chinese citizens.

[2.3] To "avoid trouble," fandom substitutes as a playground to share interests and express the self. Celebrity fandoms constitute online fandoms in China together with media fandoms, sports fandoms, and brand communities (Yang 2017). When it comes to fan practices, shipping is indispensable. Shipping is to pair "two real-life celebrities or fictional characters as a romantic and/or sexual couple" (Yang 2017, 375), whose types are male same-sex parings (boys' love, or BL, or danmei tongren), female same-sex pairings (girls' love), and heterosexual pairings. Shipping is core to "fan gossip, fan fiction (fanfics), fan art, and fan videos (fanvids)" (Yang 2017, 375). Specifically, fan fiction that pairs two real-life celebrities is also called real person slash. Most fan works in celebrity fandoms are BL narratives, especially when these fan works combine celebrity fandoms and television fandoms. A prominent example is Falling in the 227 Movement. For BL narratives in celebrity fandoms, it is a tradition for conflicts to take place between fans who "have their own 'one true pairing'" (CPFs) and "'one and only' fans who strongly oppose any shipping of their favorite stars or characters" (WFs) (Yang 2017, 375).

[2.4] The genre including gay literature, danmei, and BL narratives across Chinese fandoms is sensitive to state regulation. The state's sexual conservatism frequently targets nonheterosexual fantasies. Moreover, danmei not only takes part in the social negotiation of homosexuality but functions as an outlet for "an alternative set of relations, pleasures, and desires beyond dominant social and familial norms" (Yang 2017, 376). As a result, danmei contains graphic and deviant sex scenes, homosexuality, or gender and sexual diversity, which causes controversies involving social morality. Nevertheless, such deliberate articulation of nonnormative relations and behaviors has proved an aspiration of the young generation to navigate the intimate sphere and the public sphere (Xu and Yang 2013). When the top-down mode imposes social norms on both intimate and public spheres, the desire of the young generation to break through uniformity and conservatism contributes to systematic changes culturally, socially, and even politically.

[2.5] Accordingly, celebrity fandoms in China are, in turn, challenged culturally, socially, and politically. There were three A-listers officially banned in 2021 (as of the middle of August). Zheng Shuang, an actress, is suspected of abandoning her children born through surrogacy in the United States and is accused by the tax administration in China of intentionally evading millions of dollars in taxes. Kris Wu, a male idol, was found a rapist by the police and a sexual predator when dozens of young females accused him publicly on social media. The controversial photos of the actor Zhang Zhehan with a V-sign at the shrines in Tokyo which commemorate convicted war criminals during the Japanese invasion of China spread like wildfire as China marked the seventy-sixth anniversary of the victory of the Chinese People's War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

[2.6] While their immoral acts offended the population, what is more demoralizing in public opinion is how their fans attempt to defend them, proving that fans make an objection to political correctness and social agreement on morality when these fail to benefit idols/celebrities. For instance, Zhang Zhehan's fans legitimize his acts by constantly arguing that the social agreement that all Chinese shouldn't visit shrines that honor war criminals who invaded China is too rigid, and it is political persecution if the state decides to ban him. Such a defense strategy possibly contributes to a disbelief in state regulation.

[2.7] The politicization of fandom has become a hot topic in the public sphere, which mainly refers to the increasing political expression among fans and the appropriation of the state regulation to win the fan war. The internet watchdog, the Cyberspace Administration of China, is pushing a campaign in fandom to respond to public outrage toward immoral celebrities and increasingly obsessive celebrity fan culture. Through the campaign, the regulator has attempted to clamp down on "activities that induce minors to contribute money to their idols, hurling abuse online and doxing" and to stop "activities that encourage fans to flaunt their wealth, manipulate social media comments, make up topics online to hijack the public opinion" (Qu and Deng 2021). People's Daily, the state mouthpiece, comments that irrational fan culture disorders society, economy, and culture and intoxicates the younger generation by its negative social impacts. It indicates that the state aims at safeguarding social stability and the concern that Chinese fandoms could be or have already been used for, for example, cultural invasion, moral subversion, and propaganda against China.

3. The 227 Movement

[3.1] The 227 Movement involves roughly three different groups of fans: the WF, the CPF, and the media fans of Archive of Our Own (AO3) which is an open-source repository to archive personal fan works.

[3.2] Xiao Zhan, a male idol in China, attracted many CPFs after the TV drama The Untamed had been released, which is adapted from a danmei novel depicting a gay love story. (Hereinafter, WFs and CPFs refer in particular to Xiao Zhan's WFs and CPFs unless specific descriptions are given.) MaiLeDiDiDi, a CPF of Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo, published on AO3 Falling, a work of real person slash which tells a homosexual love story. In Falling, Xiao Zhan is, fictionally, transgender and is saving up for an operation by doing sex work, while his coactor Wang Yibo is, fictionally, a sixteen-year-old male high school student. While Falling is very popular among CPFs, WFs are irritated that Xiao Zhan would do a filthy job and seduce a teenager (fictionally), both of which are illegal and immoral in China. In WFs' mind, the fiction is maliciously designed to damage his public image and contribute to negative comments and thus triggered the 227 Movement. On February 26, 2020, a few WFs on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, organized a campaign to report illegal erotic content to state bureaus, the Cyberspace Administration of China, and the Office of the National Work Group for "Combating Pornography and Illegal Publications." As a result, MaiLeDiDiDi abandoned the story for good. Nevertheless, WFs not only reported MaiLeDiDiDi's "misconducts" but also other real person slash creators on AO3 and other platforms. This provoked CPFs to protect fan creators and platforms by showing resentment toward WFs' reporting and censorship. CPFs' counterstrike is endorsed by media fans who value friendly and encouraging platforms to share fan works. On February 27, 2020, the hashtag #227Unity (227 datuanjie) became a hit topic on Weibo's trendy list and gained more attention from other netizens. Later, the shutting down of AO3 in China exacerbated the anger of media fans, especially those who share and deeply interact with others on AO3. Although the shutting down of AO3 should not be regarded as a direct result of WFs' reporting, WFs' actions did make AO3 a target of cyberspace regulations. Hence, media fans started to cancel Xiao Zhan and his fans on social media by, for instance, publishing nasty comments about his works on the review website. Media fans are convinced that Xiao Zhan is to blame, for he failed to discipline his fans (mostly WFs) when they crossed the boundary to offend other subculture communities. On March 1, 2020, Xiao Zhan's studio published an apology letter under pressure. Instead of appeasing criticism, the apology dissatisfied media fans and induced them to cancel Xiao Zhan more radically by expressing their dislikes of brands endorsed by him and producers in the entertainment industry, because they regarded the overdue apology as Xiao Zhan's remedy for his interests. As a result, a few brands dropped advertising and ended commercial contracts with Xiao Zhan.

[3.3] Media fans joined the fan war when they shared the feelings and anger of CPFs. However, CPFs, in turn, began to cool down their disapproval of WFs to prevent the movement from overheating, out of concern that it would become a terrifying scandal for Xiao Zhan. When that failed, CPFs decided to object to the movement, though they started it at the very beginning (table 1).

| Fandom | In the Early Stage of the Movement | In the Late Stage of the Movement |

|---|---|---|

| WFs | Objectors | Objectors |

| CPFs | Supporters | Objectors |

| Third-party | Supporters | Supporters |

4. Methodology

[4.1] In the previous section, I applied historical analysis to examine the social structure, the political indifference shaped by it, and the relative practices in Chinese celebrity fandoms. In the later sections, the social structure and the perception of the public and the private are further analyzed through specific discursive practices during the 227 Movement. The discursive practices are examined by firsthand research and secondhand information including public documents from administration, news from media with official credentials and social recognition, and academic journals.

[4.2] With platformation of social media and datalization of fandom, Weibo functions as the primary site for celebrity fans; it is the largest microblogging platform in China (Yin and Xie 2021). Chinese fandoms, as spiritual utopia for younger generations (Yin 2018), are prone to keep a distance from the public and are more interested in finding like-minded peers. In contrast, celebrity fans seem to gain much visibility on social media like Weibo, where some of them even adopt a new identity as data fans. As a result of platformation and datalization, fans "strategically seek to impose their presence, using knowledge of the impact of data as statistics (quantities and metrics), and an understanding of how semantic data can influence an idol's popularity and contribute to this traffic; increasing the commercial and cultural value of idols" (Zhang and Negus 2020, 501). Such a strategy is more noticeable for fandoms of celebrities counting upon their popularity, who often are categorized as liuliang mingxing (data traffic stars). Xiao Zhan is a popular data traffic star in China, suggesting a reason why Weibo became the major platform for the 227 Movement.

[4.3] Tweets from fans on Weibo are a research resource, composed of two sets. The first are the tweets of Xiao Zhan's fans gathered and distributed by three Weibo accounts: @TroublesStartWithXiaoZhan, @AssociationOfVictmsOfXiaoZhan, and @FanworksOf227 (note 1). As an active participant of online fandoms myself, I witness how those three Weibo accounts serve as important mediators for media fans to communicate and exchange information, lead discussions, and record the lasting impact of the movement. Specifically speaking, the three Weibo accounts take the role of curators. Media fans who support the 227 Movement recorded the tweets of Xiao Zhan's fans, captured screenshots, and sent them to the curators by direct message, in order to record irrational acts of Xiao Zhan's fans. Finally, the curator accounts gathered, selected, and distributed those screenshots, often clustered by topics and issues (table 2).

| Account | Abbreviation of the Username | Followers (as of April 23, 2021) /thousand | The First Visible Tweet after the 227 Movement |

|---|---|---|---|

| @起肖蔷 | @TroublesStartWithXiaoZhan | 310 | October 31, 2020 |

| @肖某事件受害者互助 bot | @AssociationOfVictimsOfXiaoZhan | 46 | June 14, 2020 |

| @227 优秀产出 Bot | @FanworksOf227 | 25 | April 27, 2020 |

[4.4] Notably, those three Weibo accounts are fan created and fan run to archive tweets, animation, reports, and discussions related to the 227 Movement. As of April 13, 2021, seventy-seven tweets are collected as valid.

[4.5] The second set of collected tweets is based on the first part. Among the seventy-seven tweets from the first part, yeren (savage) appears in ten tweets, while "227" appears in eight tweets, which are the top two keywords among these which are directly related to the 227 Movement. "Savage" is the nickname of the movement's supporters when Xiao Zhan's fans communicate with one another. Those curators became more active in 2021. Therefore, I collected tweets on Weibo with keywords "227" and "savage" from January 1, 2021, to April 13, 2021.

[4.6] There were 432 tweets collected as valid. Stratified random sampling is applied considering fans' tweets as time sensitive regarding topics and frequency. For example, fans tweet more actively when songs, albums, TV shows, and so on are released. In order to conduct a fair comparison between the two sets, one hundred tweets are sampled, with twenty-four in January, thirty-two in February, thirty-nine in March, and five in April (table 3). In the analysis of tweets, fans refer particularly to Xiao Zhan's fans unless specific descriptions are given.

| Month of Tweets | Total of Tweets | Percentage of the Total | Number of Samples |

| January | 102 | 24% | 24 |

| February | 140 | 32% | 32 |

| March | 167 | 39% | 39 |

| April | 23 | 5% | 5 |

| 432 | 100% | 100 |

[4.7] I apply content analysis by coding of sampled tweets, cluster analysis of topics revealed in the coding, and correlation analysis to unwrap how sets of topics are entangled with one another in the discursive practices during the 227 Movement. It is worth noting that all collected tweets are directly related to both the celebrity fandom of Xiao Zhan and the 227 Movement. All tweets are eliminated if explicitly published by other celebrity fandoms or media fandoms.

[4.8] The research procedure includes three phases. The first phase is the preliminary coding. Those tweets are categorized into either "against the 227 Movement" or "in favor of Xiao Zhan" and assigned by one main topic, considering the majority of the tweets are rather short. The second phase is to recode those tweets based on the first phase. The first phase provides a basic scope of topics. The recoding phase records all topics mentioned in each tweet and incorporates similar topics in the first phase. The third phase is to examine the correlation among topics by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient. As a result, any two topics have one Pearson correlation coefficient. The higher Pearson correlation coefficient one pair of topics processes means it is more likely that the two topics appear in one tweet.

[4.9] Last but not least, all tweets collected are entirely public information on the day of the collection. All identities and personal information including usernames and specific date of publication are concealed. And it is strictly prohibited to discuss the identity of certain individuals, considering a perplexing change in attitude during the movement, the elusive standard to identify WFs, CPFs, and antifans, and the privacy issue.

5. The discursive practices in the 227 Movement

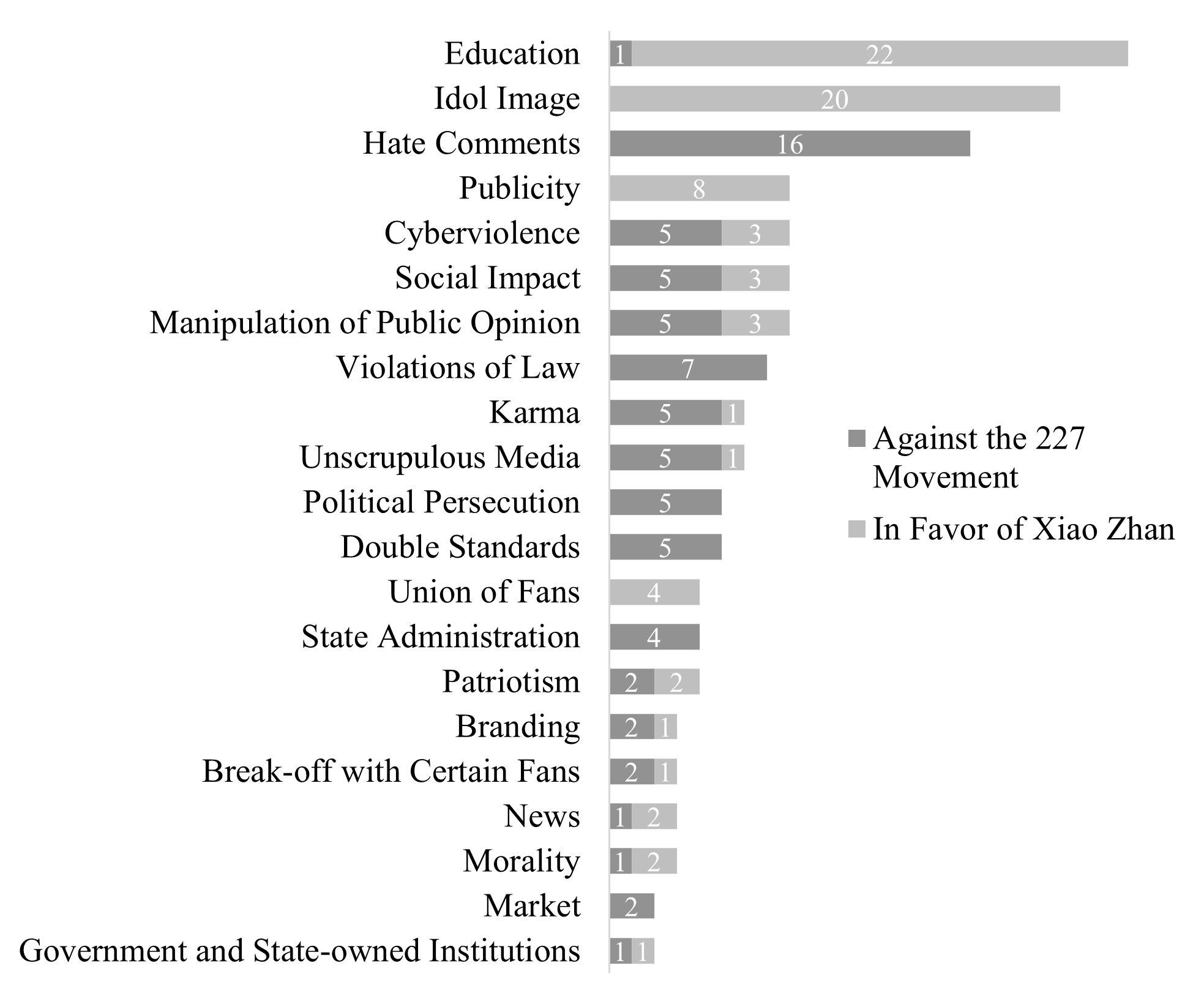

[5.1] Analysis of fans' tweets distributed by the curators: As demonstrated by figure 1, the top three topics of those tweets are education (twenty-three tweets in total), idol image (twenty), and hate comments (sixteen). By categories, the top three topics of tweets "against the 227 Movement" are hate comments (sixteen), violations of law (seven), and cyberviolence (five). The top three topics of tweets "in favor of Xiao Zhan" are education (twenty-two), idol image (twenty), and publicity (eight).

Figure 1. Fans' tweets distributed by the curators. Created by the author.

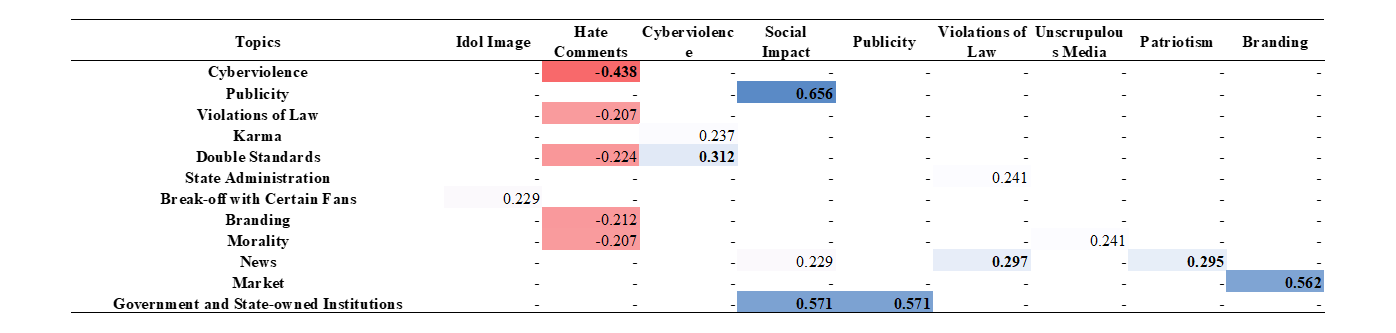

[5.2] In total, there are twelve pairs of topics with cluster effect (ranked by relevance): (1) cyberviolence and break off with certain fans, (2) social impact and state administration, (3) violations of law and state administration, (4) hate comments and karma, (5) social impact and violations of law, (6) morality and government and state-owned institutions, (7) branding and market, (8) social impact and news, (9) unscrupulous media, (10) political persecution and government and state-owned institutions, (11) education and idol image, and (12) morality and news (figure 2).

Figure 2. Correlated topics among the fans' tweets distributed by the curators. Created by the author.

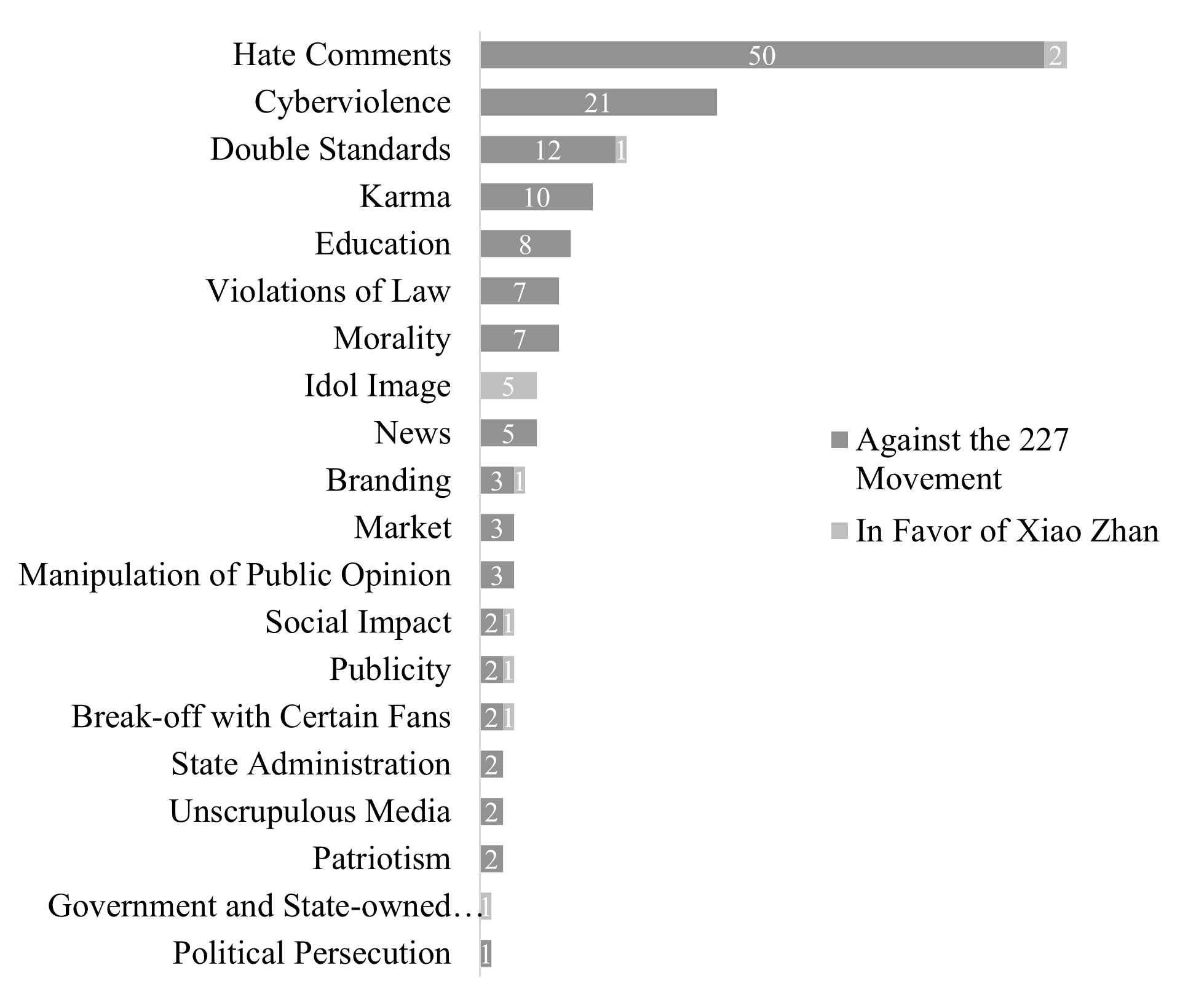

[5.3] Analysis of fans' tweets with the keywords: As illustrated by figure 3, the top three topics of those tweets are hate comments (fifty-two), cyberviolence (twenty-one), and double standards (thirteen). By categories, the top three topics around "against the 227 Movement" are hate comments (fifty), cyberviolence (twenty-one), and double standards (twelve); and the top topic around "in favor of Xiao Zhan" is idol image (five) as overall only thirteen tweets are categorized as such.

Figure 3. Fans' tweets with the keywords. Created by the author.

[5.4] In total, there are seven pairs of topics with cluster effect (ranked by relevance): (1) social impact and publicity, (2) social impact and government and state-owned institutions, (3) publicity and government and state-owned institutions, (4) branding and market, (5) cyberviolence and double standards, (6) violations of law and news, and (7) patriotism and news (figure 4).

Figure 4. Correlated topics among the fans' tweets with the keywords. Created by the author.

[5.5] The common ground: Both sets of tweets indicate strong positive correlations among social impact, state administration, government and state-owned institutions, and violations of law.

[5.6] When critiquing and expressing resentment toward the 227 Movement, fans tend to embed societal and governmental issues into commercial issues, such as publicity, branding, and market. The tweets of publicity, branding, and market target fans and cohere certain fan communities instead of promoting Xiao Zhan's works and image to the mass population. Such appropriation seems unnecessary since it takes an inherent faith and love for an idol when one claims to be a fan. On the contrary, it serves as justification and endorsement for elusive love. There is a famous saying in Chinese celebrity fandoms that fans fall in love at first glance with the good-looking, but only high moral standing could make love last. How could fans decide whether Xiao Zhan is a man of high moral standing? They interpret the actions of the government and state-owned institutions.

[5.7] When promoting a TV show that Xiao Zhan starred in, one poster tweets: "Thanks to Daddy CCTV for supporting Xiao Zhan and comforting us [who suffer from the 227 Movement]! From this moment on, 227 has a new meaning—re-broadcasting [the TV show] at CCTV!" CCTV, the official mouthpiece of the state, started to broadcast the TV show on February 27, 2021, the first anniversary of the 227 Movement. Fans interpret this as a recognized endorsement of Xiao Zhan and authoritative criticism of the movement. Moreover, the three pairs of topics also indicate correlations to a sure extent: (1) hate comments and karma, (2) cyberviolence and karma, and (3) violations of law and state administration. The three pairs suggest an expectation of overwhelming power.

[5.8] The correlation between cyberviolence and karma suggests an old belief: "An ill life, an ill end." In those tweets, fans thought about karma when discussing the suicide of a supporter of the 227 Movement. Widely accepted in China, karma is the destiny happening to one and one's family members designated by one's acts ruled by goodness and evilness. While Buddhism originally takes it as a way of self-discipline and targeting the spiritual world beyond one's reincarnation, fans believe that it is a warning that boycotting Xiao Zhan, which fans define as cyberviolence, would make the movement's supporters miserable. A few questions could be probed here. First, why do fans take one personal decision (the suicide) as a warning for a group of people (the supporters)? Second, how does karma become a consensus when discussing this matter? Karma, in essence, is featured with the family-oriented self. In a word, one's conduct is not merely regulated by kinship and consanguinity but could also bring about a result for one's family members. Under the circumstances of the movement, the adaptation of karma proves that the family-oriented self transforms into the fandom-oriented self with a similar ripple pattern in Chaxugeju. On the one hand, fans' faith in karma is communicated within the community and expressed strongly for a short time. Eight out of ten tweets related to karma were published in March. On the other hand, such faith reflects fans' underlying belief that any conduct in fandom could not be regarded as a single agency. As the ripple pattern means a network grants families and clans the top priority, the suicide incident is no longer an act of an individual agency but maps onto a collective influence where fans read it as a warning to all supporters of the movement.

[5.9] Tweets on violations of the law claim illegal fundraising, immoral earnings, and cult status among the movement's supporters, especially key opinion leaders. Those are intractable topics in China, where the first two could be easily related with resentment toward capitalists and the latter with Falun Gong, a cult organization against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). For instance, one tweet says: "[They are] not [the supporters] of the 227 Movement, not savages, not who boycott [Xiao Zhan], BUT criminal suspects."

[5.10] Moreover, fans' mania is often compared with the religious cult in China. As a result, during the movement, both sides are eager to demonize the other as cults. A Weibo tweet "Good night, I am here" from the central government agency for combating cults aggravated the fierce battle in the first few weeks of the movement, because a proportion of both belligerent parties believes it implies the fan community of Xiao Zhan was defined as an organized cult. Subsequently, the supporters of the movement trumpet it as a legitimacy, while Xiao Zhan's fans regard it as state-wide cyberviolence targeting Xiao Zhan, which requires a strategy to turn the table. Though far-fetched, it is not to substantiate the implication that matters but to develop a beneficial narrative. For Xiao Zhan's fans, such agenda-setting could mold the movement as an unlikable influence; therefore they actively combine the discussions of related news and state administration with the movement and supporters. A fan tweets when Peng Bo, a former senior figure in the offices for cult affairs and heretical religions, is accused of corruption: "#PengBoFacedInvestigation: Isn't it savages that put a label [on others]? Your Qinchao [an influencer] said fans are all Falun Gong. Oh yes, in the eyes of savages, other people are not Chinese citizens." Similar tweets on Peng Bo present an ingenious strategy. First, it converts the implication into Peng Bo's abuse of power to undermine the legitimacy claimed by the supporters of the movement. Further, it suggests the supporters of the movement are antagonistic to the state if they don't advocate the ruling.

[5.11] Curators versus fans: When comparing, there is a significant gap on certain topics, indicating political issues are utilized to attack dissenters in Chinese celebrity fandoms.

[5.12] The first is media. Among the fans' tweets distributed by the curators, fans question media literacy and media ethics, accusing media of being an accomplice in the cyberviolence toward Xiao Zhan, all of whom intend to utilize the popularity of Xiao Zhan to stir eye-catching discussions and profit. Among the fans' tweets with the keywords, fans accuse supporters of the movement of double standards: "I reiterate savages of the 227 Movement widely conducts double standards. They leave comments [under irrelevant tweets] to curse [Xiao Zhan] and, at the same time, accuse fans of dominating the commentary area. What a bunch of psychos! Savages are cheap and deserve to die, LOL!. Weibo [should establish] a real-name registration system and let me take a look at their disgusting faces!" (note 2).

[5.13] The second is political persecution and patriotism, considering there is a significant antithesis between them. By agenda-setting, the curators present a few tweets where fans deem it is "a sick state" and call for "national demise" because the state sits on its hands when the 227 Movement cruelly oppresses an innocent and arduous idol, while the fans' tweets with the keywords barely unfold this topic. As for patriotism, among the fans' tweets with the keywords, one sheds light on how fans apply it to increase their legitimacy: "I found that some mad savages of the 227 Movement are really going crazy. Why don't you critique so many [other] brands that boycott Xinjiang cotton? All you do is to tell me that Xiao Zhan is the spokesman of Li-Ning [and boycott Li-Ning as well]. Your mum was not yet born when Li Ning won the honor for our country! You are talking nonsense here!" Li Ning is a famous gymnast in China, who lit the Olympic Torch at the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games opening ceremony. Li-Ning, the local sports brand with a patriotic founder, is the best footnote for fans that Xiao Zhan is doubtlessly a patriot who contributes to local business development. Pointing out that Li-Ning insists on Xinjiang cotton, which is banned by the United States, connotes that boycotting Xiao Zhan equates damaging local business and patriotic entrepreneurs who root for the country.

[5.14] Last, the curators give greater exposure to topics on education. These tweets notably involve class, teachers, and students. The intentionality is highly related to public opinion on teenager fans in general, which is partly navigated and interfered with by the state. The curators concretize fans' mania and respond to the government's discouragement of such fandom behaviors. As a result, Xiao Zhan's image shown in those tweets usually relates to bewitching beauty. It exhibits a scenario where teachers and students appropriate class for promoting Xiao Zhan, which is believed to be against societal and parental anticipation. By contrast, among the fans' tweets with the keywords, fans find fault with the supporters of the movement as less literate and cultivated to signify that fans are good students who meet society's expectations.

6. The politicization of Chinese celebrity fandoms in the 227 Movement

[6.1] Scholars comment that online fandoms in China are playing platformized language games combining connectivity and data-driven metrics of social media with their personal and communal experience as fans (Yin and Xie 2021). Setting up the principle of popularity and datafication imposes a fear of annoying the public about celebrity fandoms and, in turn, "significantly influence how fans interpret the social environment on the platform and how they behave within it" (Yin and Xie 2021, 16). A remarkable manifestation is censorship and surveillance conducted through the state's cyberspace policy.

[6.2] Cyberspace policy as a political tool: In 2017, a hit TV show, The Rap of China, made PG One, the majority of whose fans are young, a popular rapper in China. Later, PG One's affair with a married female celebrity led to the public's ostracism of him. When it stirred the social media, Ziguangge, the authoritative mouthpiece of CCP, took it as an example to warn adolescents about predatory behavior and drug abuse he bragged about in his raps. His fans, however, were convinced it was newsjacking as they mistook Ziguangge's Weibo account, which is also named as Ziguangge, for a restaurant with a similar name; they then struck back by hiring ghostwriters to slander it for using illegally recycled waste cooking oil and successfully made #ZiguanggeWaste-cooking-oil the trending topic on Weibo (note 3). Afterwards, PG One was officially banned from Chinese media. Though the fans' counterstrike was ironic, the government is deeply concerned with such mania of fandom, which might corrupt the young generation and instigate disbelief in social harmony.

[6.3] It is the first time Chinese fandoms realized that the administration is a potent regulator of cyberspace and fandom. It explains why, at the very beginning of the 227 Movement, key opinion leaders of WFs targeted AO3 and guided others to seek administrative assistance by posting links to the report and compliant page on the government website with careful wording. It indicates sophistication in agenda-setting and comprehension of cyberspace policies. In a word, the cyberspace regulation policies provide instrumentality and legitimacy for Chinese fandoms to seek help from the administration and expect to close the dispute for good by utilizing it as a powerful tool.

[6.4] The appropriation of the political discourse and textual practices: In Teahouse, Lao She says that "posted everywhere are notices: 'Don't discuss state affairs'" (1980, 6). Originally, the teahouse refers to "the meeting room for all works of life accommodating people from all levels, and thus, a micro-society," where "the changes of their life display the transitions of the society," "inexplicitly revealing political messages" (Lao 1958, 93). Weibo has become the urban successor of teahouses, reaching 249 million daily active users on average (Sina Weibo 2022). This leaves the young generation with a paradox. On the one hand, they are discouraged from discussing state affairs. On the other hand, Weibo offers them a lens to political messages and social issues inexplicitly revealed by social media users from all aspects.

[6.5] Due to constantly being told to hold their tongues, the young generation is not provided with an option to devote to political debates. According to Jenkins, fandom is a marginalized subculture, where fans poach and recreate textual practices, and "the largely female composition of media fandom reflects a historical split within the science fiction fan community between the traditionally male-dominated literary fans and the newer, more feminine style of media fandom" (1992, 48). Likewise, the politicalized discourses might act as a subversive impulse for Chinese fandoms to restore their discourse.

[6.6] A news story portrays the readiness to fight for Xiao Zhan among his fans: "The phone dropped from the hand holding it for over forty hours when Xiao Ya passed away. Xiao Ya, a freshman in a university, is a fan of Xiao Zhan, who adores the idol in a mothering way. In the past few days, she was on the 'patrol' using ten Weibo accounts, so that she would go for a diss and trash-talking once encountering any nasty comments of Xiao Zhan" (Peng 2020).

[6.7] It has been argued that Chinese fandoms practice the right to boo. Under the fear of fandoms' energy, power, and collective wisdom, the booing leads to "the loss of free speech and dignity to be placed nowhere" (Liang 2020) among practitioners in the entertainment industry and other cultural commodity consumers.

[6.8] Such fear contributes to a sense of belonging and empowerment and an encouragement to strengthen it among Chinese fandoms. In fact, the movement is not the first time that Xiao Zhan's fans have utilized the reporting system and embedded political messages. Prior to this, fans reported Yan Ning, a scientist, for academic fraud because she refused to watch The Untamed and was fed up with recommendations from Xiao Zhan's fans. Plus, fans gossiped about a critic in the entertainment industry, Cheng Qingsong, about having a homosexual affair with another male writer because he criticized Xiao Zhan's poor performance so as to discredit him as a public figure (Half-day Entertainment 2019).

[6.9] Furthermore, during the movement, the discursive practices in the fandom of Xiao Zhan were camouflaged as the call for justice for all and caring for underaged netizens. The declaration of @巴南区小兔赞比 to encourage reporting writes: "I, today, don't speak for my idol, but for all stars who are suffering. Stars are deeply afflicted by the nasty real person slash, who, out of their public images, can't even speak and reclaim justice for themselves. Malicious real person slash harms more than one star and lasts after today. When will such unscrupulous slandering under the name of freedom [in writing] and misconducts attacking others' reputation come to an end?" Such a statement was designed to unify irrelevant celebrity fandoms.

[6.10] More significantly, mentioning "all stars who are suffering" strengthens the sense of legitimacy that the reporting is for the public good. It answers the question why WFs targeted platforms like AO3 instead of Xiao Zhan's real person slash. Otherwise, they would make it an act of private revenge, which wouldn't gain the support of the mass population. It reflects the longstanding perception of gong and si (the public and the private), where the public has the exclusive and absolute legitimacy to seek justice. Furthermore, to win public sympathy, WFs replaced the dispute around real person slash and Xiao Zhan's public image with public concern about whether the wild spread of fictions containing adult content, like Falling, leads to misconduct among adolescents. Many WFs believe they helped the state correct the wrongdoings of those platforms: "A platform [referring to AO3], which is non-compliant with laws in China, keeps feeding the younger generations with danmei literature and pornography! So why can't the state intervene? The Ministry of Education has done a really good job and I admire it very much."

[6.11] Meanwhile, CPFs retaliated by putting forward a slogan, "Free writing! Literature Not Guilty!" The strong slogan on free writing hit the hearts of media fans, the majority of whom enjoy various fan works and danmei novels. They not only empathized with CPFs but shared the rage about innocent subcultures being punished after the ban of AO3.

[6.12] In essence, expressions from both sides function as not merely a discussion about social issues such as privacy, dignity, and free speech but also as an appeal to all outsiders for their empathy. Scholars argue, "Whether they are agents of formal institutions or living subjects, each, depending on the circumstances, will forge alliance with other forces, such as enterprises that may have relevant interests, or contend for the chance to build relationships with the media or with experts. Probing the way interactive subjects strategically unite with or fight against other forces and the way their behavior influences the development of events is thus an essential perspective that cannot be ignored by the 'institutions and everyday life' perspective." (Xiao 2015, 85).

[6.13] The appropriation of social and political issues in the public sphere exemplifies the politicized discursive practices in Chinese celebrity fandoms shaped unconsciously by political intentionality and philosophy to eliminate private interests (Liu 2003a). It may achieve a categorization where the private runs in the realm of fandom, if, traditionally, the private represents a personal and family life. The innate cause of the 227 Movement is a desire to guarantee a personal experience involving celebrities among Chinese celebrity fandoms by increasing influence. However, celebrity fans and media fans inevitably appropriate the public good as evidenced by the two expressions in the 227 Movement. Behind the calling for respect for every individual, including celebrities, is a personal imagination for a flawless idol image. Covered by the calling for free writing, there is a secret desire to explore personal life that might be immoral. The relation, the public versus the private, serves as the reason why Chinese celebrity fandoms during fan wars must make claims for public interests to ensure the support of the mass population and the state.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] The 227 Movement unwraps the politicization of Chinese fandoms. However, the movement is not an independent incident in Chinese fandoms. When studying the structure of fandom, Lv Peng and Zhang Yuan point out fandom is a spontaneous organization where the young generation performs social activities in cyberspace, but those social interactions present universality (2019). The politicization of current fandom is a synthesis of different factors. Overall, three factors are considered in the research: Chaxugeju, cyberspace policies, and the long-standing perception of gong and si.

[7.2] Although displayed less directly in those tweets, Chaxugeju is reproduced in Chinese fandoms and impacts how fans communicate with one another. To start with, the structure of Chinese fandoms resembles the family-oriented self. Chinese scholars notice the topology of Chinese fandoms frequently is shaped by loyalty and obsession (Lv and Zhang 2019). The more loyal and obsessed one becomes, the more one is recognized to the core. Moreover, a similar structure to the family-oriented self prevails in fandom in respect of individual identity and sentiment. When frequently interacting with other fans in the fan community, one transfers the identification of the self as a fan to the community as fans (Zeng 2020). By contrast with the family-oriented self, it is the community-oriented self.

[7.3] The reproduction of Chaxugeju in Chinese fandoms unwraps why the tweets' topics show a pattern of aggregation, which demonstrates that the forming of ideas is driven by the fan community. There is a significant similarity to adopt double standards as a defending strategy and applying karma as a shared response to suicide. The aggregation applies to the content as well. Tweets reveal a pattern of describing the supporters of the movement as "illiterate," "stupid," and "brainless," which takes up half of the fans' tweets with keywords on the topic of education. Unlike the hierarchical organizational structure, fans' communicative network is similar to the ripples of influence. The Chinese word fanquan, identical to fandom, is transliterated as a fans' circle. The linguistics exhibits the similarity between the Chinese pattern as ripples in Chaxugeju and fans' networking. Instead of replication, each fan conveys an agreement on topics and issues in a personalized story. The ripple pattern guarantees uniformity and autonomy in Chinese fandoms.

[7.4] Cyberspace policies condition and shape the political discursive practices in Chinese celebrity fandoms. Cyberspace policies and regulations have the capability to convey a strong political message about social issues and morality (for instance, the CCP's Core Socialist Values), which later is utilized to win fan wars, but only when, in the opinion of fans, idols could benefit from it. When idols don't benefit, they make an objection. It explains the polarization of those tweets where some fans delightedly conclude the state supports Xiao Zhan when CCTV decides to run his show while others claim the state persecutes him politically by pampering and encouraging haters. More significantly, those political propositions prove that Chinese celebrity fandoms are seeking influence beyond their reach, intentionally or not.

[7.5] Furthermore, Chinese fandoms show a growing relationship between who discusses politics and the pursuit of influence. In PG One's incident, his fans mistook Ziguangge for a restaurant. Three years later, Xiao Zhan's fans connect the corrupted anti-cult official with the movement even though the anti-cult office is not a well-known bureau to many citizens. In short, political indifference as an inherent feature of the young generation should be reconsidered. The relation, the public versus the private, might serve as the reason why fans seek public support by making claims for the public interests.

[7.6] In conclusion, Chinese celebrity fandoms are seeking social influence and participating actively in agenda-setting in the public sphere, developing into political communities, and engaging the young generation in political expression.