1. Introduction

[1.1] Warhammer, a British tabletop war game, has garnered a loyal following in China, prompting an exploration of the unique characteristics of Warhammer fan culture in the country. We provide an overview of this culture, including a description of Warhammer's basic background information, Chinese fans' interests in translating and promoting the culture, their behaviors of consumption, differences between Warhammer's video game and tabletop game fan culture, and potential threats posed by media censorship and rising nationalist sentiment. By examining the political, economic, and cultural factors that shape the development of Warhammer fandom in China, we demonstrate how the country's distinctive conditions have given rise to a fan culture that sets it apart from its UK counterpart.

[1.2] In 1975, Games Workshop (GW) was founded in London, England, to produce board games (Games Workshop 2021). Today, it is one of the most successful companies in the miniature war-game business and owns three main production lines, including Warhammer 40K, a tabletop and video game set in a science fiction universe; Warhammer: Age of Sigmar, a tabletop only game with fantasy elements; and Warhammer Fantasy Battle, a video game only. Furthermore, GW has actively expanded overseas. Around 2007, the first shop selling Warhammer military products appeared in Shanghai, China, according to a post on Chinese video-sharing website Bilibili from user An Jing Ling Ye Feng (May 21, 2022).

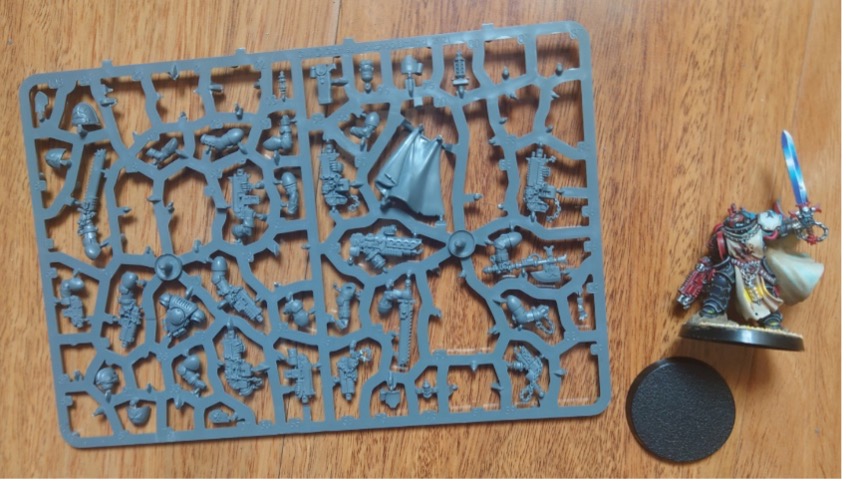

[1.3] After finding a shop to buy the miniatures, players still need further steps to prepare their game. These miniatures are sold unpainted and need to be assembled, and these processes are completed by the players (figure 1). After this, players need to learn the rules to build their own army with various miniatures. To have a fair competition, GW's codex, or official rule book, gives each unit a cost in points according to its attributes, including weapon abilities, moving distance, and special skills. Players decide the point scale of the game and each player then must spend that many points on their army. All players' army lists must have the same point value (for example, a 2,000-point game). A headquarter, for example a commander who can add a benefit to the team, such as an effect that increases attack power, could take more than 100 points, but an infantry squad (ten models) could take only sixty. Players play with similar points, so organizing these points smartly is the foundation for victory. One game could take players two to three hours or longer, which does not include the hundreds of hours of building and painting the miniatures. This hobby is costly, too. The most popular Warhammer 40K game, The Combat Patrol: Space Marines Box, is £90 and worth 600 points. The tool kits to build and paint the items are also required, including glue, a modeling knife and clipper, a brush, and paints. Ideally, the gamer needs at least £300 to build a mainstream, beginner, 1,000-point army to play on the table. As YouTube user Headywon joked in 2021 on a Warhammer 40K army build guide video about the exorbitant cost: "How to Build a 40k Army: Step 1: Finding a Second Job."

Figure 1. The sprue of a model and the finished model. Photo by Peilin Li.

[1.4] Not only are money and time necessary, but also community. Playing alone is impossible for the tabletop player, and that makes fandom community a vital characteristic. The tabletop game is designed to promote social interaction and enhance the social experience (Zagal, Rick, and Hsi 2006; Cova, Pace, and Park 2007). Whether playing a tabletop game or discussing painting skills, Warhammer is a social activity (Harrop, Gibbs, and Carter 2013). During a series of interviews, Cova, Pace, and Park (2007) found that "[t]he notion of friendship was mentioned several times as the main reason why the enthusiasts hang out together."

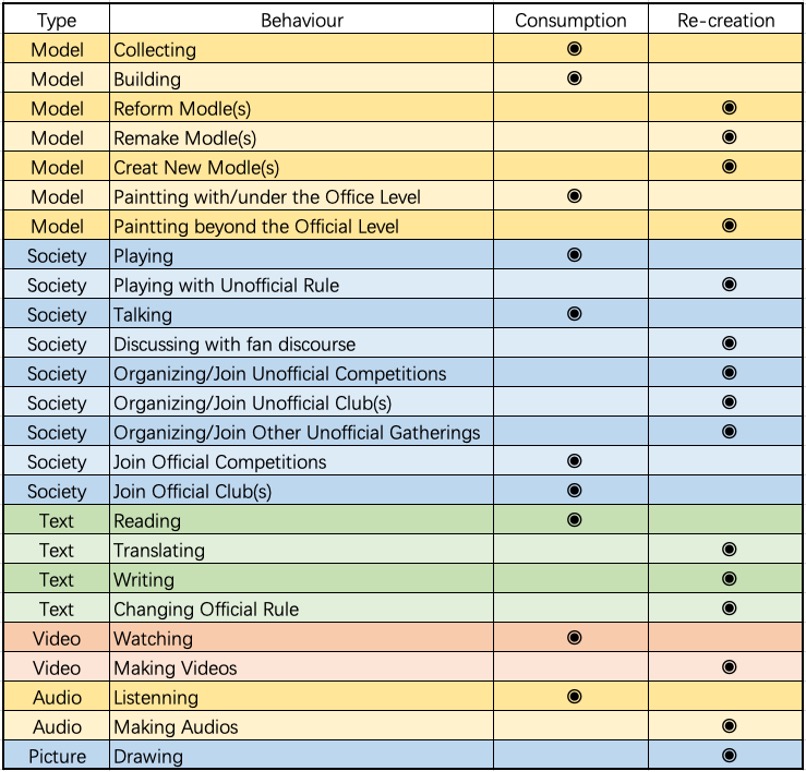

[1.5] Warhammer is not limited to tabletop games but has been adapted to official and fan-made fiction, movies, video games, comics, and many other types of content. As a result, GW describes its customers as "collectors, painters, model builders, gamers, book lovers and much more" (Matthews 2021). The definition of fandom in this article is based on participatory culture: That is, consumers take part in the production and recreation of content (Postigo 2008; Jenkins 2012). Warhammer fandom involves more than just consuming the hobby; it also includes various activities in which fans participate to recreate and expand upon the content (figure 2). As China's context differs from that in the UK, fans have adopted distinct ways of experiencing the game, developing their community, and formulating relative culture.

Figure 2. The behavioral classification. List made by Roland Wang.

2. Fan labor and translation

[2.1] Chinese fans dominate the promotion of Warhammer culture. In 2021, GW organized a series of off-line activities in China. For example, Armies on Parade, the official annual painting competition, opened its gate to Chinese players. GW registered its branch company in Shanghai in 2011, but the team of the Games Workshop China (GWC), lacking a consistent business strategy, has been frequently reorganized. Its laggard development and poor business decisions make it hard to offer help in promoting Warhammer culture. In contrast, fans have played a dominant role in the promotion of the game through translation, trading, and introducing this hobby to others, according to a post from user Mao Mu Shi on Bilibili in 2020. For example, fans volunteered to work with video game website Game Cores to operate a broadcast series in April 2017, introducing the story of Warhammer 40K without any support from GW. As of December 2022, there had been thirty-four episodes of the series and their average views had numbered around 100,000 on Bilibili. Because of fans, many Warhammer-themed cultural products, such as fiction, rule books, and videos, were translated into Chinese between 2017 and 2020, and numerous fan-created works, including worldview introduction, painting guidance, and consumption advice, are widely spread around the internet. At the same time, according to Bilibili user Biao Mian Kan Kan DM (2022b), the number of Warhammer enthusiasts experienced steady growth. In July 2020, GW released the ninth edition of Warhammer 40K Core Rules, which is the first official rule book in Chinese. Before that, all translated editions relied on fan support. Even after the official Chinese version of the rule book launched in China, Chinese fans still used fan-translated rule books in most cases (Biao Mian Kan Kan DM 2022b). Such phenomena reveal that the translation is dominated by fandom.

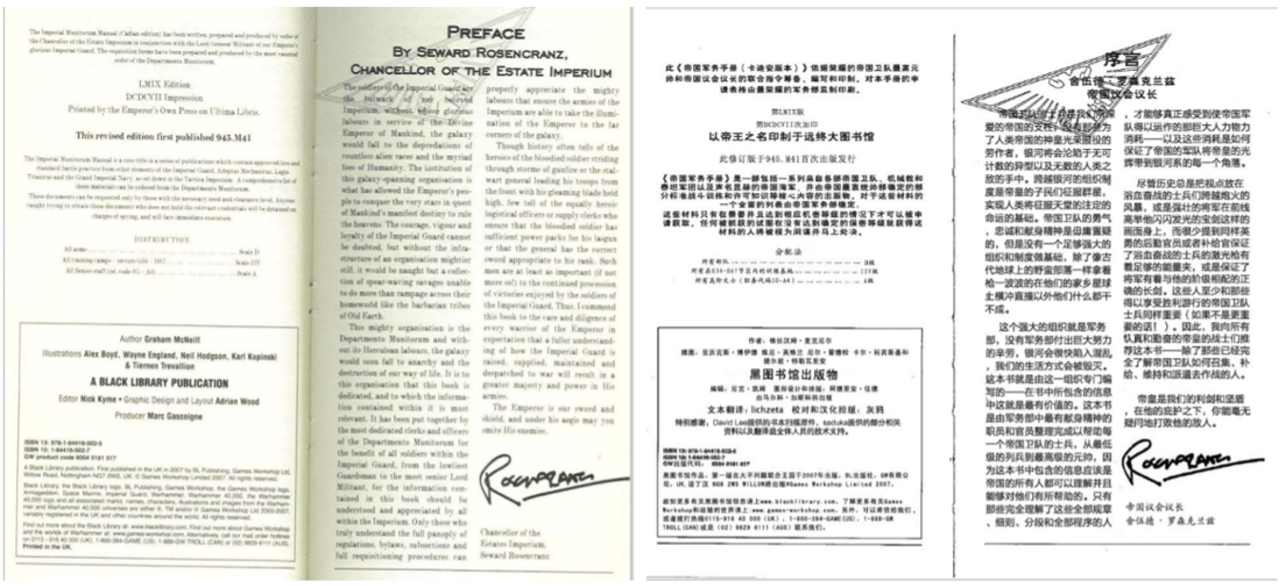

[2.2] Translating plays a vital role in Chinese Warhammer fandom activities. Warhammer's translators have the nickname translationorum (Fanyi Ting). This name is borrowed from the Officio Assasinorum, which is a secretive agency that commits assassination in the story of Warhammer 40K. Initially, translationorum was a specific fan translation group founded in 2011 (Arzael 2011) and it was the first group to translate a whole book and keep the original English composition (figure 3). Today, translationorum is not one organization but an identifying description that encompasses all translation behaviors. There are two characteristics worth noting about translationorum. Firstly, the content translationorum translates is flexible, including not only translated official materials—for example, rule books, novels, and animation series—but also fan-made content such as memes, videos, fiction, or even Reddit posts. An excerpt of an excellent fighting scene might also be translated and posted on social media. Secondly, many translators only do the job in their spare time, so the translations sometimes are fragmented. Comments such as "Call translationorum" or "Praise translationorum" can be found under the videos in English. Anyone who is watching the video can get involved and be a part of translationorum. This activity and sphere of helping each other is also an important form of fandom recreation (Khaosaeng 2017). By naming themselves with Warhammer terminology, translators reinforce their fandom identity (Soukup 2006), promoting community development.

Figure 3. The book The Imperial Infantryman's Handbook translated by translationorum. This comparison image in both Chinese and English versions of the book was created by Peilin Li. The copyright of the English version of The Imperial Infantryman's Handbook belongs to the GW.

3. Fan economics

[3.1] Similar to fan translation, spending habits also reflect fandom culture in China, with the most remarkable one being protecting local shops. Experienced UK fans suggest beginners trade preowned miniatures with others to save money. In contrast, in China, the suggestion is to go to local stores, because most local Warhammer communities are centered on physical stores whose survival relies on customers. Additionally, GW's pricing strategy and supply capability create challenges for physical stores in China, with GW products typically priced 30 to 40 percent higher than those in the UK. Also, they are often out of stock, putting off-line stores at risk of closure. Therefore, it is not a surprise that some old fans will be frustrated if someone compares prices too aggressively or buys pirated products. Although fans try to maintain the Warhammer community, the higher price makes it more difficult for beginners to get into the tabletop game.

[3.2] People in China also have relatively low income and expenditure. In 2021, urban residences' per capita expenditure on education, culture, and entertainment was ¥2,599 (China's National Bureau of Statistics 2022). Normally, the cost of a medium-sized Warhammer army, which amounts to $1,000 (Harrop, Gibbs, and Carter 2013), is above a city inhabitant's ability to purchase. Moreover, the high cost brings responsibility. If a beginner lost a Warhammer game because of someone's suggestion about buying army miniatures, that person might publicly blame the suggester. The dispute could sour the relationship within the relatively small fandom community in China. Economic conditions not only determine how Chinese fans allocate their money to pursue the hobby but also fundamentally shape Chinese Warhammer culture.

[3.3] Pirated video games provide Chinese players with free access to the Warhammer universe, promoting Warhammer culture. Each way of consuming Warhammer culture is independent of the others. For instance, an audience can watch a Spider-Man movie without having to buy the comic. Similarly, there is independence in the ways in which Warhammer products are consumed. Tabletop Warhammer players can merely focus on the physical game, separate from consuming video games, while video gamers can enjoy virtual gameplay without purchasing tabletop war games. In 2004, the video game Warhammer 40,000: Dawn of War (DOW) let Chinese players know what Warhammer is (Biao Mian Kan Kan DM 2022). Due to the availability of pirated copies of DOW (Rawlinson and Lupton 2007; Cao and Downing 2008), Chinese netizens freely played and shared the video game that they should have paid for. Without DOW, Chinese consumers had very limited access to the Warhammer culture and were largely unaware of its existence, as the first store selling Warhammer opened in 2007 and the first online community appeared in 2006. In the early days of the online community in China, the discussion about DOW was far greater than that about the corresponding tabletop game (Biao Mian Kan Kan DM 2021). The DOW inspired Chinese video game players to explore Warhammer tabletop games. In other words, pirated copies of DOW spread through the internet and became instrumental to the popularity of Warhammer in China.

4. Censorship

[4.1] As a crucial component of the internet environment in China, censorship imposes potential risks for the spread of Warhammer culture. Censorship limits the freedom of speech of netizens and results in political pressure (Biddulph 2015; Miller 2018) and therefore changes the way people communicate and has triggered self-censorship (Chang and Manion 2021). Fans avoid talking about violent and pornographic Warhammer-related characters and plots in online discussions to prevent triggering censorship. Discussing content that is forbidden online might result in penalties for the speaker themselves, such as removal of the content and/or banning of the account, and also might stimulate censorship of Warhammer video games. Because of censorship, numerous in-game components have to be reworked (Cao and Downing 2008; J. Zhang and Chiu 2020; Dong and Mangiron 2018; L. Zhang 2013; X. Zhang 2012). A typical attempt to prevent censorship of what might be deemed pornographic content involves modifying characters who wore low-cut clothes or who were topless in the original game so that they instead appear in what is perceived as a more appropriate costume (figure 4 and figure 5). To prevent violence and bloodshed, in the shooter game Player Unknown's Battlegrounds (PUBG), the red color of blood has been changed to green (figure 6). If the game operators did not make such changes, the games would be taken down. Up to now, Warhammer games have not been subjected to Chinese censorship. In order to avoid unnecessary repercussions for Warhammer games, fans generally tacitly avoid pornography and violent topics. However, active discussion of politically sensitive issues by fans of Total War: WARHAMMER III (TWW3) causes censorship, which brings risk to Warhammer culture.

Figure 4. A male character in the game Food Fantasy was required to reduce the level of physical nudity at least twice. This is an example of the censorship of nudity content in video games. The original images were created by Funtoy Games.

Figure 5. The female character Shiranui Mai in the game Honor of Kings was asked not to be overly sexy, hence her figure and clothes have been altered. The character Shiranui Mai was originally created by the Japanese video-game company SNK.

Figure 6. In the game PUBG, the original image featured red blood (left), but in China the color of blood was changed to green (right). The two game screenshots are from PUBG developed by PUBG Studios.

[4.2] Originally, Total War and Warhammer were two different games. The former is a turn-based strategy and real-time tactics video game. In its twenty-two year history, most of the works of the Total War (TW) series have been based on conflicts in real history (Webb 2022; Sukhov 2015), such as the Napoleonic Wars and the American War of Independence, and players usually command an army in a real historical setting on computers (Spring 2015). Total War: WARHAMMER III is the third game that the Total War series created within the Warhammer Fantasy Battle setting. In short, TWW3 allows video game players to lead the military, which fights with swords and sorcery, winning the war through a turn-based strategy and real-time tactics in a world reminiscent of a darker Middle Earth. Although there is no specific investigation focusing on the difference between fans of the Total War series and those of the Warhammer tabletop war game, the TW series fans tend to follow and discuss political issues (McCall 2018; Spring 2015). In contrast, Warhammer's fan culture is not political. Even though fans of the games discuss political topics in the Warhammer world that are similar to those in human society, such as the struggles and consequences of different political factions within the Human Empire, it can hardly be considered a discussion of real political topics, because Warhammer is set entirely in an imaginary world. TWW3 combines the story of the Warhammer Fantasy Battle and the gameplay of the TW series, which gathers Warhammer fans and TW series fans and ultimately blends the two cultures. Since then, TWW3 fans have been able to use the discourse from the Warhammer Fantasy Battle to discuss real-world political issues.

[4.3] In China, openly expressing political views disapproved by the authorities may attract punishment; for example, the user is likely to be banned. Thus, netizens tend to avoid the risks (Chang and Manion 2021). TWW3 fans are more concerned with current political topics than others. They share their political-commentary videos along with their gameplay videos. There are concerns that if these fan-video creators are banned from a platform due to current-affairs-commentary videos, it could result in removal of their gaming videos. For instance, on the Chinese video platform Bilibili, Influencer A, who was well known for videos about Warhammer Fantasy Battle history and TWW3, gained attention because of frequent comments about the war between Russia and Ukraine. Influencer A spread a rumor that "Russian special forces will turn the tide of war by marching stealthily to suddenly capture Kiev" as the "Sub-space raid hypothesis" with high probability. In the Warhammer setting, the subspace transfer technology allows rapid transport of troops to designated destinations. In China, the discussion of the war ran the risk of being censored, whether the position was neutral, opposed, or supportive (Wade 2022; Wang 2022). Hence, Influencer A finally stopped updating any content about the war. When fans discuss sensitive themes, their Warhammer fandom identity and unique discourse might help to avoid censorship. However, such discussion, in turn, may trigger an investigation of Warhammer culture itself.

[4.4] The growing nationalism on the Chinese internet (Y. Zhang, Liu, and Wen 2018; D. Zhang 2020) is another potential threat. In TWW3, a gamer must choose a player's racial identity to join the war, and there are many fantasy races that can be chosen. As one of the newest and most popular races in the TWW3, the Cathay are designed following traditional Chinese culture. The appearance of the Cathay brings about two different opinions in China. On one hand, fans feel happy that Chinese elements are well presented in the video game. On the other hand, fans are concerned that the Cathay are not perfect enough. For example, the Cathay is not the most powerful race, and there are heroic characters who do not fit the Chinese aesthetic. Thus the netizens who know neither Warhammer nor TWW3 culture might consider these games insulting to their country. If the misunderstanding that these two games insult China is not cleared up in time, the games could be blocked in mainland China. Fortunately, as of now, there have been no censorship or banning incidents against Warhammer video games. This may be because the number of Warhammer fans is so small. However, media censorship and online nationalism in China has always been a sword of Damocles hanging high over Warhammer culture.

[4.5] Although the media and gaming censorship in China does present a barrier to Warhammer players discussing pornographic and violent topics, a new video gaming policy provides an opportunity for Warhammer culture to grow in popularity. As Chinese authorities limit the length of time that underage players can spend online, parents are actively looking for off-line entertainment as an alternative, and Warhammer is becoming an option for some families, a situation noted by Bilibili user Biao Mian Kan Kan DM (2022b) as well as Mozur and Chen (2021). No one can predict how much Warhammer games will benefit from this change in policy, but an unstable media environment is always a threat to the development of Warhammer culture.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] We have discussed Warhammer culture in China and how unstable sociocultural conditions threaten cultural markets and activities. Although censorship has an impact, the level of fan income has a greater influence on the survival of Warhammer fan culture in China. The economic, political, and technological differences between China and the UK breed different fandom behaviors and culture. Firstly, we have explored how tabletop war games became popular in regions with limited economic development. Secondly, we found that the economy, not censorship, is the key factor influencing the popularity of expensive cultural products and related fan culture in China. Thirdly, we acknowledge the crucial role played by fans' free labor and creative behaviors in the dissemination of costly cultural products such as Warhammer. The data in this article are based partially on the authors' experiences and observations in the two countries, and this is one of the rare comparisons of the cultural differences between fans of the same cultural commodity in two different social contexts.