1. Introduction

[1.1] In global fandom, the term "Mary Sue" refers to a character who is so perfect and without weakness as to be unrealistic (https://grammarist.com/new-words/mary-sue/). The term originated in A Trekkie's Tale, fan fiction written by Paula Smith in 1973 (Mansky 2019), which aimed to satirize the idealized female characters common in Star Trek fan fiction (Smith 2011). This genre usually features female heroines who are young, attractive, and exceptionally gifted and who serve as the author's self-insertion into a story (Fazekas and Vena 2020) where the perfect female protagonist is able to win the preference of the male character (Bacon-Smith 1992). Mary Sue stories in the Chinese context, usually written by teenage female fans, are mostly recognized as works of shameless self-projection and self-indulgence (Zheng 2016), with fans imagining themselves as the female protagonist in the stories, perfect and attractive to all. In the Western context, Mary Sue represents the teenage girl suddenly finding the power of her sexual attractiveness (Smith 2011). Fazekas and Vena (2020) believe that such characters provide an opportunity for teenage girls to write themselves into popular culture narratives as the heroines of their own stories while opening up a gateway for writers, particularly women and members of underrepresented communities, to see themselves in extraordinary characters (Mansky 2019). Moreover, "for intelligent women struggling with their culturally anomalous identities, Mary Sue combines the characteristics of an active agent with the culturally approved traits of beauty, sacrifice, and self-effacement, which magic recipe wins her the love of the hero" (Bacon-Smith 1992, 101).

[1.2] This practice soon evolved beyond the female character into Gary Stu (or Sue), which describes a male character with similar characteristics: unrealistically perfect, handsome, and powerful enough to protect the female character. In the sense described by Fazekas and Vena (2020), Gary Stu characters can be understood as an opportunity for teenage girls to write a perfect Mr. Right for themselves in their own stories and see themselves being pursued by him in their favorite ways. "Sue" has been widely used as an adjective to describe characters or celebrities who are good-looking, romantic, charming, and thoughtful; it has also been adopted as a verb to describe a character/celebrity's flirting that makes fans sexually excited. As distinguished from Sue in the Western context, which highlights the female character's power, perfection, and sexual attractiveness, Sue in the Chinese context describes the traditionally ideal characteristics of a man: handsome, wealthy, elite, gentle, thoughtful, masculine, and protective. In Chinese fandom, which consists mainly of female fans, using "Sue" as a verb refers to self-insertion on the passive side: being protected and taken care of by masculine celebrities, as in the traditional heterosexual norm.

[1.3] However, in recent years, a noticeable fandom movement of reverse Sue has emerged in the Chinese context, in essence blurring the line between masculinity and femininity and challenging the gender dichotomy. It primarily refers to (especially female) fans' imagining themselves as the strong male role (e.g., boyfriend, older brother, father) to their idol's weak female role (e.g., girlfriend, sister, daughter); the fans take on a seemingly powerful active role where they protect and look after their male idols. Nisu fans use the Chinese word 泥塑 (clay sculpture) to describe their fan activities. This word associates Nisu practice with the mother goddess Nüwa in Chinese mythology and vividly captures the gender-creating spirit of the fandom. Just as Nüwa creates humanity by playfully molding figures from yellow earth, Nisu fans reshape genders by freely assigning feminine traits to male public figures, and occasionally masculine traits to female idols. Nisu activities have different forms, one of which sometimes involves sexual fantasies where female fans imagine penetrating their male objects (who are imagined to be in female form) through their imaginary phallus. The other form relates to fans' parental care of male objects as daughters or little sisters. In this sense, from female fans' viewpoint, their male idols need not be powerful and masculine; rather, they are better soft and vulnerable, which shows an opposite meaning to Mary Sue in the Western context, in which the ideal man should be powerful and masculine. In addition, because the Western Mary Sue female character is often placed in the passive position and narrated to sexually attract the male protagonist, Chinese fans show particular proactivity in placing themselves in the seemingly active position when initiating Nisu activities (note 1).

[1.4] Nisu activities echo McRobbie's (2009) model of the phallic girl, proposed in the postfeminist theoretical framework and based on Butler's (1990) queer theory of the phallic lesbian as a political figure who competes for power with the patriarchal authority by mimicking men or becoming a phallus bearer. The phallic girl notion seemingly avoids rearranging the gender hierarchy, displaying the pretense of gender equality insofar as women are approved to behave in a manly and aggressive manner. Adopting the phallus enables women to have power while reducing the critique against masculine hegemony. McRobbie (2009) argues that youthful female phallicism is an alternative masquerade strategy that allows young women to be empowered but with the strict condition of becoming masculine, thus ensuring gender restabilization. This pretense of equality is presented and promoted in consumer culture as a challenge to feminism and a triumph for the revivification of the patriarchy. In this sense, we detect that Nisu fans have the potential to form a counterculture by defying the traditional heterosexual norm, at least in the fandom context.

[1.5] Chao (2017) has investigated male cosplayers' theatrical performance of cute female characters, which presents an intriguing inconsistency between socially anticipated proper gender expressions and assigned gender in today's China. Their performance of femininity contributes to queer spaces within the mainstream heteronormative environment in China. In the same vein, Yang and Xu (2015) have also discussed the genre of body change (male to female and female to male) written by women responding to their readers' strong desire to imagine a world without fixed gender roles, particularly expressing women's voices against the gender norms of the current Chinese social discourse. However, we do not attempt to investigate how Nisu fantasy is expressed nor how it relates to postfeminist discourse and consumer culture. Rather, we focus on interaction within the fandom by exploring how Nisu fans, as a rebellious subcultural group, negotiate with a mainstream culture that is dominated by the traditional heterosexual norm. We argue that although their internal divergence and self-contradiction may weaken this resistance, female Nisu fans express their subversive potential by seeking the power of the imaginary phallus to defy male hegemony.

2. Literature review

[2.1] The objects of Nisu began with xiao xian rou (little fresh meat), a term originally used by Chinese fans in 2014 to label Korean idols. It is an expression imbued with sexual innuendo, subverting a cannibalistic metaphor more commonly used to refer to women (Zhang and Negus 2020). It refers to teen or young male celebrities presented with exquisite makeup, delicate skin, and exaggerated elegance. These features conform to Jung's (2011) notion of "manufactured versatile masculinity" in the Korean entertainment context—a type of "multi-layered, culturally mixed, simultaneously contradictory, and most of all strategically manufactured" masculinity (165). Triggered by this type of masculinity, which many Chinese celebrities present, Nisu fans extend their fetishized objects to a wider range of public figures, including male e-sport gamers, program presenters, and social media influencers, regardless of their styles, images, or temperament (note 2). The Nisu activities depend on the prosperity of idol production and consumption in the Chinese entertainment industry, where consumerism can be seen as a token of free and liberal expression through which participants make their own choices to pursue individual desires and pleasure (Fung 2009).

[2.2] In academic literature, Zhang and Negus (2020) discuss multiple factors that led to China's "little fresh meat" idol industry following the influence of Japanese and Korean idol production. Zhao and Wu (2021) conclude that fans' consumption practices are motivated by both intrinsic motivation (sensory pleasure) and extrinsic motivations (a sense of being needed and feeling success). Fung (2009) canvasses the interrelationship between fans' engagement with the political regime by arguing that youngsters' preoccupation with consumption and addiction to idols diverts them from critical discourse on civic engagement, which undermines state legitimacy. In this way, fans' individual attitudes and pursuits are an apolitical response to the Chinese politicoeconomic context, which might be seen as a safe solution for the state to keep youngsters pacified.

[2.3] Fan engagement has a significant impact on both celebrities and their studios, as well as on media content production. Fung (2019) adopts the term "fandomization" to demonstrate the influence of fans' participation on online video content or production. Fans, as data labor (note 3), contribute to traffic data, which is dematerialized as a new affective object in fan-object relations, thereby constructing a type of algorithmic culture (Yin 2020). Moreover, a fan community has also been considered as a speech community, where the language and discourses of fan activities rely on technology, primarily on social media platforms (Yin and Xie 2021). Beyond fan participation, some particular types of fandoms have also been studied, such as animation, comic, and game lovers (Yin and Xie 2018).

[2.4] As a newly risen subcultural group, Nisu fans have not yet attracted much scholarly attention. In Anglophone scholarship, Nisu subculture has only been researched in one conference proceeding, which analyzes the blended gender representations of Zhehan Zhang (Lin 2021), one of the leading actors in a boys' love (BL)-adapted drama, Word of Honor (Youku, 2021). In Chinese-language scholarship, seven publications in the CNKI database, including three master's theses, have emerged, researching the relationship between Nisu and BL (Xiang et.al 2021), Nisu fans' motivations (Yang 2021), practices in reality shows (Huang 2021), manga (Meng 2019), sexual desires (Zhao 2022), and gender politics (Chen and Huang 2021; Chen et al. 2021). While some of them show an inaccurate definition of Nisu activities (e.g., Huang 2021), most of them neither demonstrate a systematic methodology nor articulate the data with well-explained cases. Further, although some authors claim to use semistructured interviews or textual analysis as methods, both methods are poorly explained, with few details on the recruitment of participants, interview questions, or results of analysis. Nisu research thus lacks scholarly attention that adopts a nuanced theoretical approach and systematic methodology.

[2.5] If the construction of Mary Sue can be viewed as a form of women's empowerment in popular culture by breaking women's stereotype of being vulnerable (Chander and Sunder 2007), then Nisu activities can be seen as a challenge to the traditional heterosexual mindset by gazing at men, turning them into imaginary women. This can be interpreted as a form of female gaze, responding to Mulvey's (1975) male gaze and referring to the gaze of the female spectator, character, or director of an artistic work. The female gaze has been seen as a visual parameter to examine heterosexual female sexuality (Schauer 2005) contributing to a deconstruction of mainstream representations (Dirse 2013). The female gaze has been highly visible in a Chinese entertainment industry affected by consumption culture. A typical example is found in male celebrities frequently acting as spokesmen for female cosmetics, utilizing their beautified and sexualized appearance to boost women's consumptive power. Li (2020) argues, "The shift from 'male gaze' to 'female gaze,' and the consumption of sexualized men, appear to be revolutionary in terms of evaluating gender power; however, Chinese female consumers' agency and self-empowerment are still limited by a conditioned neoliberal consumerist culture" (55). In a similar sense, Nisu fans' activities are a kind of spontaneous participation, triggered by male stars' attractiveness and female sexual fantasy, but with an inverted power relation.

[2.6] While Nisu fans express their fantasy through posting on Weibo, commenting on their idols, and creating fan fiction, fan art, videos, and emojis that represent their idols as female, fan fiction (note 4) has become a vital space to showcase fans' inverted sexual imagination. Fan fiction has long been researched as part of the erotic texts created by or for women in the global context (Russ 1985 [2014]; Penley 1992); the majority is written by well-educated women who often include explicit sexual depictions in their works (Jenkins 2012). However, Chinese fan fiction has not attracted much academic attention, being subject only to sporadic studies that all focus on slash fan fiction (Yang and Bao 2012; Fang 2021). This study does not aim to examine Nisu fantasy through fan fiction, or vice versa. While acknowledging Nisu fan creations in various forms, we pay attention to Nisu fan activities and the patterns of the Nisu fandom community rather than to the texts they produce.

[2.7] Nisu fantasy has had its unique value compared with other types of fan fiction in which male stars are sometimes constructed as women. Gender transformation is a common subgenre of fan fiction, especially in slash fiction, which often portrays the male object as a female character. In this genre, the character has female physiological functions (e.g., menses and reproductive function), but her gender behavior is hardly changed and is still consistent with the original male object's personality. Another subgenre, male pregnancy (Mpreg), shares a similar sense in that it allows the male character to have both male and female sexual organs without changing his original behavioral pattern. Although the narratives of this genre transgress biological and gender binaries to conceive queer futurities via romantic fantasy (Wood 2021), "Mpreg thumbs its nose at traditional heteronormative 'family' values by creating the gay family as 'nature.' The pregnant partner always demonstrates the nurturing and emotional boding associated with pregnancy, while the other partner is cast in the traditional protective role of father" (Hayes and Ball 2009, 232). Nevertheless, Nisu texts construct a different value by endowing male objects with traditional female personality traits, such as being tender and caring and wearing beautiful dresses and decorations. As the subgenres of gender transformation and Mpreg do not undermine male power by feminizing male objects, we believe Nisu activities better bear the potential to subvert male-female power relations. As such, by focusing on the patterns of the Nisu fandom community, we explore how Nisu fans interact with other types of fans and negotiate with a mainstream gender discourse dominated by traditional heterosexual norms. As a burgeoning subcultural group, female Nisu fans express their subversive potential by seeking the power of the imaginary phallus to defy male hegemony, although their internal divergence and self-contradiction may weaken this resistance.

3. Methods

[3.1] Our research adopts multiple methods, including online observation, participation, and in-depth interviews. First, we, the authors, who have participated in the Nisu fan community for more than two years, position ourselves as semi-insiders in the Nisu communities, helping to understand fans' communications and diminish their hostility to outsiders (Hills 2002). We are regular users of various media platforms that are highly popular in the Chinese entertainment field, including Sina Weibo and Lofter, which facilitated our online observation and participation from July 2019 to March 2021. We are also members of fan groups with open WeChat Moments and other social media pages, thus allowing other group members to be aware of our stances. This approach paved the way for recruiting qualified interviewees and summarizing the interview themes in our project's second stage. While the first approach helped us detect the basic pattens of Nisu fans' online interaction with other types of fans, the interviews contributed to our investigating their attitudes toward and insights into Nisu activities and their strategies for negotiating the mainstream gender discourse dominated by the traditional heterosexual norm.

[3.2] Second, we adopted snowball sampling strategies to recruit nine interviewees, organized into two groups: (1) five self-described Nisu fans, who have been members of the community for two months to three years; and (2) four self-described anti-Nisu fans, who oppose Nisu activities. All of our interviewees were straight females, including influencers on both Weibo and Lofter. For group 1, we included three active Nisu fans who actively produced fan fiction, fan art, videos, and peripheral products, while the other two interviewees were more passive, primarily viewing and enjoying other fans' material without producing anything. The interviews adopted open-ended, semistructured questions centered around three themes: (1) fans' journeys involving Nisu activities, including perceptions and incentives; (2) Nisu fans' online interactive patterns/strategies and self-censorship; and (3) the impact of Nisu activities on fandomization. The ethical review was approved by the ethics committees at the first and second authors' affiliated institutions in 2021. Our interviews were conducted both face to face and online through phone call or WeChat call, with prenotified audio recording. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants before the interviews. All the names of the interviewers appearing in this article are pseudonyms. Interview data was encrypted and was only accessible to the authors. Audio recordings containing sensitive and private information were transcribed by the second author.

4. Internal divergence and external conflicts

[4.1] On the bases of our online observation and in-depth interviews, we detected that although the nature of Nisu activities consists primarily of female fans' sexual fantasy about their idols, fans' acceptance of the male objects' (in the guise of females) sexual depiction largely varied. Some accepted very few or even no sexual hints when discussing or commenting on their idols, because they still believed Nisu to be shameful and that it should not be open to the public. For those who could accept the sexual portrayal of their idols, some were fine with talking about Nisu in public yet resolutely rejected immoral or incestuous sexual depiction—for instance, imagining the male object as the female fan's stepmother and having sex with her (interviewees X and G). Other fans did not feel offended by immoral or incestuous sexuality but insisted that Nisu activities should be strictly limited to their own fan communities, never reaching the wider scope of the fan circle (interviewees H, W, and Y). In fans' daily practice, they followed the Quandi Zimeng rule, which means that Nisu fans should use abbreviations or code names when talking about their fantasies in order to avoid the idols' names being found in certain posts via the Weibo search function (Wang and Ge 2022). The purpose of such a rule is to ensure that Weibo search results are in line with mainstream values, meaning that Nisu fantasies are outside the range of acceptable content for the mainstream. This is similar to McRobbie and Garber's (2006) view of subcultures, where fans form a kind of "defensive retreat" to avoid restrictions and judgements by those who identify with the dominant culture.

[4.2] However, the interviewed Nisu fans' mentality was often changeable and sometimes contradictory. Interviewee H claimed that her degree of acceptance of sexual portrayal could change if the stories were attractive enough or if the sexual depictions truly served the plotlines. Interestingly, a recommendation from a friend in the same fan community was the main reason people changed their attitudes toward Nisu activities. Interviewee W felt uncomfortable about Nisu fans in the beginning but became one of them when more than half of her friends became fond of Nisu fantasy.

[4.3] Nisu fans not only show diverse acceptance levels of sexual delineation but also have varied incentives to engage with Nisu activities. Apart from enjoying the sexual fantasy, some people label themselves as Nisu fans and produce relevant materials to fit into the community, driving traffic in order to make themselves visible, leading fans. As Bai (2022) demonstrates, fans are recognized by their collective identity. Hence, they tend to endow themselves with certain labels to distinguish themselves from others, thereby helping them to fit into the communities. "Organized fandom is, perhaps first and foremost, an institution of theory and criticism, a semistructured space where competing interpretations and evaluations of common texts are proposed, debated, and negotiated and where readers speculate about the nature of the mass media and their own relationship to it" (Jenkins 2012, 88). Thus, we can see that the Nisu fandom community, as a semistructured space, constructs the Nisu discourse for fans to engage with and plays an impactful role in motivating them to reevaluate their own fan status and their relationships with peers.

[4.4] Because most Nisu fans enjoy acting as the imaginary penetrator of their male idols (in female form), some coupling fans who enjoy the imagined romance between two male stars like to fantasize about one male celebrity being penetrated by the other (in the heterosexual mode). For instance, interviewee W mentioned that the Nisu activity could be extended to her slash fantasy to satisfy her imagination of sexuality between the couple. For these coupling fans, the Nisu activity is contradictory. On the one hand, it shows the reserved gaze when the feminine male star is placed in the passively penetrated position; on the other hand, it endows the masculine star with the privilege of penetrating. The coupling fans' Nisu activity is analogous to Yukari's (2015) view of the "amusementization of sex," which is based on the analysis of the genre of BL, particularly male-male romance stories. The genre has been called by Yukari "a thoroughly gender-blended world" in which "women are freed from the position of always being the one 'done to,' and are able to take on the viewpoint of the 'doer,' and also the viewpoint of the 'looker'" (84). Yukari goes on to explain that in the all-male world of BL stories, no biological sexual difference exists; thus, creators are able to make couplings by combining all sorts of gender factors and power dynamics as they like. Similarly, Nisu fans search for their own preferred couplings among all the possibilities offered.

[4.5] Apart from coupling fans, the divergence is also embodied through the Nisu attitudes of the so-called Only-fans, who exclusively worship one male celebrity rather than consuming an imagined romance between two male stars (Wang and Ge 2022). These Only-fans tend to imagine their idol as their daughter and eagerly keep other bad men away from him (her). For instance, interviewee H believed that she could not accept her baby daughter (her male idol) having a relationship or even any sexuality with another man. "It is too obscene!" interviewee F claimed, also stating that some Nisu fans prefer to see their idol as a noble princess who is attractive to all men, but no one deserves her. She can be pursued but cannot be had by anyone. This type of Nisu mentality reflects Only-fans' self-projection of being independent from men while imposing their own self-protective sense onto the male idol (in female form) in order to shape him (her) into their preferred image. In this sense, some Nisu fans tend to substitute male stars for themselves in order to imagine that they themselves can have beauty, wealth, privileged social status, and a network, enjoying people's worship just like the stars (interviewee F). However, despite Nisu fans' subversive potential, their self-projection inevitably presents their prepositive mind-set of appreciating femininity from a traditional perspective (e.g., being slim and young, having bright and white skin), thus echoing the male gaze.

[4.6] As a form of female sexual fantasy that takes an antitraditional heterosexual mode, Nisu activities are restricted to a marginalized subcultural group and struggle with strong opposition. According to our interviews with anti-Nisu fans, where some express the rather misogynistic opinion that imagining their male idol as a girl is belittling him (interviewees L and J), others hold the completely opposite stance, claiming that it is inappropriate to use complimentary adjectives usually used to describe women's virtue to represent male stars because this action supports male hegemony. Interviewee C stated on November 29, 2021, "I hate men. Men do not deserve [the praise]. Those complimentary adjectives should describe particular virtues belonging to women only. Nisu fans endow their idols with many virtues. [Fans see the idols through their filters]. When the filters are deleted, their idols are just very normal male university students or labor workers in entertainment industries." Although C expressed her hatred of men here, this hatred seemingly did not stop her from adoring male stars. Thus, although Nisu and anti-Nisu fans showed opposite attitudes toward Nisu activities, neither of them was entirely against male hegemony, as anti-Nisu fans still tended to worship male celebrities in their own ways, albeit not in a Nisu manner.

[4.7] Although Nisu and anti-Nisu sides tend to collide with each other, they can reconcile when anti-Nisu fans find that Nisu activities can bring fame and commercial profit to their idols. For instance, although most Nisu fans favor male celebrities who are tender, caring, and effeminate, these male stars are more likely to attract endorsements of feminine products or invitations from parent-child reality shows because advertisers and production companies can utilize Nisu gimmicks to boost sales and audience rating.

[4.8] However, conflicts between the Nisu and anti-Nisu sides do not solely focus on competition over territory in a celebrity's fan club; they also involve the perception of gender norms. A typical case is the "227 incident" of February 27, 2020. This incident occurred in the fandom of the popular Chinese BL-adapted drama The Untamed (Chen Qing Ling; Tencent TV, 2019). In February 2020, fans of the main character, Xiao Zhan, organized a collective action on social media to report the fan fiction of a fan who wrote homosexual fantasy between two male stars. The novel, titled Xiazhui (Falling), concerns a homoerotic story between Xiao (as a transgender prostitute) and another actor, Wang (as an underage high school student). This act of collective reporting led the Chinese government to block the international fan platform Archive of Our Own (www.archiveofourown.org, abbreviated AO3) on February 29. This conflict denied thousands of Chinese fans access to AO3 to read, distribute, and create fan works, which further exacerbated mainstream society's negative attitude toward fan culture and directly led to a series of cultural policies to regulate fan culture (Wang and Ge 2022). This case can be explained by Simons and Taylor's (1992) psychosocial model of fan violence in sports, which states that when a unitive identity is formed and internal solidarity is enhanced in a fan community, conditions make extreme actions possible. Although the 227 incident was not violent, it can be seen as a hostile attack by anti-Nisu fans against the Nisu community, taking advantage of state power to profoundly affect the whole community of fan fiction creation. It demonstrates the predicament of nonmainstream fan groups, exemplified by Nisu fans, who are repeatedly rejected and even suppressed by mainstream culture (Larsen and Zubernis 2012). Moreover, in 2021, the mainland Chinese authorities launched a cleanup web campaign; feminized male stars, criticized as a form of vulgar culture and deformed aesthetics inappropriate for teenagers, were particularly targeted (see Guangming Daily, August 26, 2021, https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404674470253035809). Against this backdrop, many celebrity studios and fan clubs declared a ban on public Nisu activities, which further implies repulsion of antitraditional sexual norms and compliance with traditional male-dominated gender norms in the broader gender discourse of mainland China.

5. Self-censorship and self-contradiction

[5.1] Although Nisu fans attempt to challenge the normative heterosexual mode, they are fully aware of their own marginality, sometimes lack confidence about their fanaticism, and present a self-contradicting mentality. This is analogous to the creation of real-person texts (texts based not on fictional characters but on real people, both public and nonpublic figures) in the BL fan community, where real-person texts are rejected and excluded from the BL fan community because of moral issues, such as respect and politeness, regardless of the self-claimed counterpublic nature of BL fandom itself (Chiang 2016). In a similar sense, Nisu fantasy is likely to trigger moral panic, and there are concerns that the explicit sexual depiction of the male objects might disturb the real people, even though the fictional plots are only fans' imaginations. Thus, Nisu fans utilize the strategies of self-censorship and keep distance from the real stars in two ways: first, by limiting the sexual depiction in their texts to show respect and also to protect themselves; and second, by calling their idols alternative names and using codes when commenting or talking about erotic topics.

[5.2] First, under pressure from authoritative censorship, particularly that targeting pornography, the majority of creators of fan-made materials proactively reduce the sexual content in their openly published works, although no official document clarifies how explicit the sexual depiction would need to be to lead to a writer being sentenced. In such a circumstance, some Nisu fans adopt a similar strategy to BL writers, utilizing metaphors portraying sexual intercourse in a lyrical fashion as well as visual metaphors (Wang 2020). Moreover, anonymously reporting materials with sexual depictions to the authority leads to writers' insecurity, which further stimulates them to internalize self-censorship in text creation (Tian 2020). In Pang's (2008) opinion, when confronting pressure from the authoritative regime, the grassroots entity shows even more vulnerability than the individual and is apt to compromise in order to avoid being eliminated. As interviewee W mentioned, self-censorship has been an established rule for fan creation, and a painting of hers was censored. If producers of Nisu works refuse to self-censor, then the media platform will likely not let their works be published.

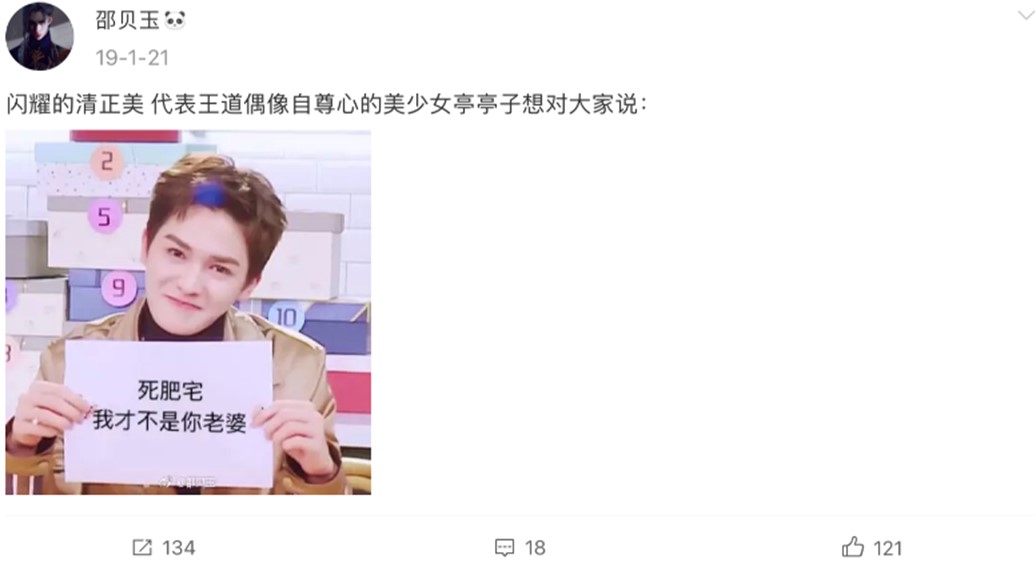

[5.3] Second, when involved with sex-related topics, Nisu fans proactively use codes to refer to male celebrities or erotic vocabularies, including abbreviation, nicknames, and homophonic substitution, as well as splitting Chinese characters. For example, Renjun Huang is called "rice cake" by his Nisu fans, while Zhengting Zhu's given name, 正廷, is often replaced by a homophonic substitution, 正婷, with the last character substituted for one with a radical of female semantic indication (figure 1). In addition, the Chinese phrase 淫秽色情 (yin hui se qing; "obscenity and pornography") is abbreviated to "yhsq," the initials of the four Chinese characters. The Chinese character 吻 (kiss) is often split into 口勿. According to interviewee X, the abbreviation is already established by common usage and has become a rule that Nisu fans follow. If idols' real names appeared in public on Weibo, Nisu fans would be attacked. Meanwhile, they are reluctant to leave any evidence on public media platforms in case someone reports them to the authorities. As interviewee W said, it might be a subconscious thought that linking idols with sexual context somehow sullies them and love itself, because Nisu fantasy only involves sexual desire, not love. Nisu fans' sophisticated self-discipline leads them to adopt the Nisu-style tags (on both Weibo and Lofter) of the male objects' nicknames or feminized substitutions rather than their real names (for self-protection), thereby limiting the Nisu community to within fans' comfort zone. As Larsen and Zubernis (2012) suggest, this activity can be analogous to fan fiction sharing, in which "the therapeutic factors of groups are interdependent; neither catharsis nor universality is itself sufficient for change" (114). Rather, fans see the expression of feelings and the discovery that others share them as important. The community's acceptance challenges the individual's fear that they are basically unlovable and unacceptable.

Figure 1. Screenshot of Nisu fan Shao Bei Yu's Weibo post on Zhengting Zhu, January 2021. Tingtingzi (亭亭子) is his feminized nickname.

[5.4] Furthermore, an interesting finding in our observation is that some active Nisu fans have extended their creation beyond immaterial texts to material peripheral products for online sales, including postcards, dolls, and mouse mats (figures 2, 3, and 4). In the selling process, they usually adopt careful self-censorship, such as using private trade and transaction modes, thus escaping both the media censors of sexual content and market and tax regulation. Sales of Nisu peripheral products suggest that regardless of a nonmainstream fan group, Nisu fans share a similar sense with mainstream fans in showcasing their fanaticism by purchasing material products as an important way of supporting their idols and proving their fan identity (O'Brien 2008).

Figure 2. Screenshot of an advertisement on Taobao, China's largest online shopping platform, showing fan-designed mouse mats based on a feminized, eroticized image of Zhehan Zhang, the lead actor in BL-adapted web drama Word of Honor (2021).

Figure 3. Screenshot of fan-designed dolls based on Korean celebrity Na Jae-min, captured in April 2021 before the picture was deleted due to censorship.

Figure 4. Selfie of Korean celebrity Na Jae-min, posted on his Twitter (now X) account on April 4, 2020 (https://twitter.com/nctsmtown_dream/status/1245638115043102721?s=46&t=auXFw24xUZtsE_tjFrZ-Ig).

[5.5] Nisu fans' self-censorship intensified after the launch of the cleanup web campaign in 2021, especially when Nisu fans' male objects and their studios aligned with the authority, propelling Nisu fans' self-contradiction. According to Xu and Yang (2021), this involves the state's subtle technique of co-opting stars as a cultural management strategy to incorporate entertainment celebrities into the government's ideological and publicity work, win popular consent, and reinforce the state's cultural hegemony and leadership. Beyond managing celebrities, this strategy is also effective in controlling fans, because the co-opted stars must support the cleanup campaign and request that their fans comply with the regulations; otherwise, fans would be punished (by blocking accounts and so on). In this way, for the purpose of protecting both their idols and themselves, fans must keep a low profile under the dual pressure of the authoritative level and the stars' fan management teams, even though most fans might be unhappy and/or assert the importance of free speech, which results in self-contradiction in the fandom community. For example, Zhengting Zhu and some other celebrities in Yuehua Entertainment signed an Action Proposal supporting the cleanup campaign on August 27, 2021. Some male stars' fan clubs, including those of Zhennan Zhou and Runqi Li, published statements to ban Nisu activities and stop fans from using womanly vocabulary to call their idols wives, princesses, and daughters (Souhu, August 27, 2021, https://www.sohu.com/a/485986830_267454; Weibo, September 24, 2021, https://m.weibo.cn/status/4681367159309005?wm=3333_2001&from=10B9299020&sourcetype=weixin). In this sense, some fans, including interviewee H, believe that Nisu is a small subcultural group that imposes members' fantasies onto idols without caring about the celebrities' own thoughts. Out of respect for celebrities, many Nisu fans would not even openly advocate for their own community on a large scale, which implies a sense of self-shame. Conversely, some other fans, including interviewee F, think that presenting the Nisu fantasy directly to idols is not an offense because they earn sky-high incomes, and a few words of fantasy should mean nothing to them. Regardless, peer surveillance remains a risk for these Nisu fans.

[5.6] All in all, despite Nisu fans' resistant potential, as a result of their status of being a minority group, they are more likely to be abandoned or boycotted by mainstream fandom members to ensure the community's survival. Some Nisu fans have joined the campaign of banning Nisu activities in order to pander to mainstream fandom and secure their fan identity in the community, which further embodies their self-contradiction. For instance, interviewee H, a Nisu fan herself, believes that Nisu activities should be limited to a small group and will do something to prevent the expansion of the Nisu subculture. In summary, Nisu fans' self-censorship is an attribute of both bottom-up peer surveillance (by both anti-Nisu fans and other types of fans) and a top-down co-opting strategy, while their self-contradiction in defying traditional heterosexual norms and being apprehensive of their own heterodoxy implies both resistance and compliance.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] Media portrayals of LGBTQ groups and lives have been subject to ambiguous yet persistent censorship in China's authoritarian and heteropatriarchal society. However, the transformation of media cultures and practices by and for gender, sexual, and sociocultural minorities make these negotiated spaces possible (Zhao 2020). Chinese fan culture is far from a subversive community that takes effort to rebel against the mainstream culture; it is a constantly negotiated subculture that adopts various strategies and evaluation systems from mainstream culture and educational institutions (Zheng 2016). Yet Nisu fans are not entirely distinctive. Nisu fans express resistance and challenge traditional heterosexual norms through their sexual fantasies of male idols, but they unresignedly admit that becoming masculine can empower them and give tacit consent to the dominant power of the phallus. This insight draws on McRobbie's (2009) assertion that female phallicism is presented as a masquerade, a cultural strategy in which female empowerment may only be achieved in a masculine style, thereby reaffirming traditional gender roles associated with Chinese values. Our discussion reveals that Nisu fans' internal divergence, and their self-contradiction within the Nisu fandom community, may weaken their resistance. However, as a rising subcultural group, we also perceive their rebellious awareness of seeking the power to break their chains and find paths to use to express their fandom. Facing public stigma and censorship, the Nisu fandom group appears to be gradually diminishing in size, with traditional girlfriend-style fans regaining dominance. Future research delving into the evolving dynamics of Nisu fandom practices and the resurgence of heteronormative fan practices offers intriguing new avenues for exploration.

7. Acknowledgment

[7.1] Research was supported by XJTLU Research Development Fund RDF-22-01-079.