1. Introduction

[1.1] If there is a golden age in the history of football spectating in England (better known in the United States as soccer), it can be argued such a period stretches from the late 1940s to the early 1960s, although recent trends in English football spectatorship suggest that, in a very different sociocultural climate, the current era offers something of a renaissance for the return of very large crowds to football (Williams 1999). In the 1948–49 season, in the postwar glow of recovery and the search for collective leisure diversion in a society that boasted full employment but was still experiencing rationing and offered few leisure options, English football generated a record 41.3 million League match admissions (Walvin 2001; Taylor 2008, 194; Phelps 2005). The majority of these attendees would have been working-class men supporting their local football clubs—the story was less clear-cut in other European countries—but there was also a sprinkling of middle-class support at English football, as well as early signs of out-of-town support requiring private travel to watch embryonic "super-clubs" (Mellor 1999).

[1.2] As social attitudes and patterns of weekend leisure slowly changed in the postausterity Britain of the 1950s, and as the new affluent worker of postwar Britain became more individualistic and more consumerist, communal sport began to lose its grip on the public imagination. Car ownership in Britain rose from 2.3 million vehicles in 1950 to 5.6 million a decade later. Television barely registered in British households in 1950, but by 1961, three-quarters of all homes had a TV set (Taylor 2008, 195). By the late 1960s, Football League admissions in England had fallen to 30 million, though these figures were bolstered by crowds at new domestic and European competitions. But from the mid-1960s, the national picture for football in England began to change in other, largely unanticipated, ways.

[1.3] As crowds continued to fall, English football began to suffer a series of crippling financial crises, and the behavior of some young male English football fans gradually evolved into a form of highly ritualized intergang violent sporting rivalry, one centered on territorial conflicts and masculinity testing in and around the country's football stadia. These same types of trends were also occurring in other parts of Europe, with crowd disorders being reported in a number of other countries, including West Germany, Greece, and Italy (Dunning, Williams, and Murphy 1984). These modern versions of historical football rituals further damaged the national and international public image of the English game (Dunning, Murphy, and Williams 1988). English football stadia introduced enforced segregation of fans by physical barriers and "pens" (Bale 1993) in order to deal with this emerging fan hooliganism in the 1970s and 1980s, but failed to keep pace with prevailing public demand for generally improved (and pacified) leisure provision. English football was also struggling to hold on to its traditional audience in the face of increasing social mobility, class dealignment and new leisure options, so that it "could no longer hold the centre of the communal stage as it once did" (Allison 1981, 134–35). By the 1985–86 season, following a catastrophic hooligan incident that resulted in the deaths of 39 supporters (note 1), the annual League attendance figure for football had almost halved, to just under 16.5 million, the postwar nadir for English football (Foot 2006, 328–40).

[1.4] A slow but persistent recovery in the sport's fortunes since 1986 was accentuated by the reflexive aftermath of another major stadium disaster, in the city of Sheffield in 1989, in which 96 Liverpool fans were killed (Taylor 1991), and by a new relationship established in 1992 between the top English football clubs and the European satellite television conglomerate BSkyB (note 2). As a result, the late-modern version of English football has been radically repositioned in terms of its preferred audience, consumption patterns, market appeal, and global reach, as well as its cultural significance (Williams 2006). New television money has also meant that many major English football stadia have been modernized or rebuilt, with seats replacing standing areas at all major venues. Fan behavior has also been modified and better regulated by the new, albeit rather suffocating, micromanagement regimes established inside English football stadia (Williams 2001a). By 2009, annual League football crowds in England had climbed close to the 30 million mark once more, with some evidence that gentrification and a recent surge in female attendance at football had contributed disproportionately to this revival in the sport's public fortunes. In typical English sports locations, such as the East Midlands city of Leicester, local fan surveys suggest that more than a quarter of regular football fans today are women and girls (Williams 2004).

2. Sports fan research

[2.1] Much of the recent growth in academic research on sports fandom has been characterized by a focus on changing patterns of sports consumption and, especially in the United States, quantitative studies driven mainly by the disciplines of social psychology and sports marketing: a largely statistical concern with unveiling the primary motivations for fandom (Wann et al. 2001; Smith and Stewart 2007; Chen 2010; Clark, Apostolopouloua, and Gladden 2009; Robinson and Trail 2005; Funk, Ridinger, and Moorman 2004). In the United Kingdom, sports fan research has been rather more theoretically informed, more qualitative, and perhaps a little more sociological. But it has also had a rather narrow base. It has typically focused on how traditional male working-class sporting fans—usually football fans—and the local audience for live sport have been challenged by recent changes in the football nexus, thus producing their recent alleged marginalization or even their exclusion from active sport spectatorship (King 2002; Nash 2000 and 2001; Williams and Perkins 1998). This is due, it is claimed, to the connected processes of gentrification, commodification, and the TV-promoted spectacularization (and consequent cultural "emptying out") that have allegedly characterized new directions in the production and consumption of much late-modern English professional sport, especially professional football (Conn 1997; Giulianotti 1999; Sandvoss 2003).

[2.2] These are important developments in the new agendas for sports fan research, but in our view there is also a tendency toward nostalgia in some of these accounts, especially concerning British sport's often exclusionary masculinist and cultish past. Moreover, relatively little attention has been focused here on the fan careers and normative experiences, over time, of female sports fans, perhaps because it is assumed that so few women challenged the male dominance of football in the 1950s—a Mass-Observation survey of British women in 1957 found that 79 percent agreed that "A woman's place is in the home" (Kynaston 2009, 573), or perhaps because it is argued today that some women have been unfairly usurping some men in the late-modern sports stadium (Crolley and Long 2001). Existing studies typically style women sports fans as dysfunctional sexual predators (Crawford and Gosling 2004), subordinate subhooligans (Cere 2003), or spectators negotiating historic forms of male sports opposition to their presence at sports events (Jones 2008). Typically, female fans are stereotyped as lacking detailed knowledge about sport or their club and, consequently, are often considered as inauthentic in their support (Crawford and Gosling 2004; Crolley and Long 2001; Kim 2004; Llopis Goig 2007). Women often emerge here as incomplete ciphers, as decidedly nouveau consumers of sport, with no identifiable or authentic sporting histories. In short, they often appear as highly contingent and, at best, highly marginal ersatz new members of the national sporting community. Our contention is that an excavation of the sporting histories of long-term female football fans in England adds more balance to this typified depiction and also to the research agenda and cultural positioning, more generally, of active female sports spectators.

3. Context and methodology

[3.1] Hill (1996, 3) suggests the overall aim of contributions to Holt's Sport and the Working Class in Modern Britain (1990) is to "investigate popular sport 'from below' and thereby gain a perspective on working-class culture and social relationships that could not be acquired by studying dominant national forms of sport." Thus, in the 1980s, some historians began to rethink their work on British sport, especially in relation to issues of social class. Indeed, Hill (1996) argued that important contributions from scholars such as Holt (1986), Jones (1986, 1988), and Taylor (1987) were actually written from a class perspective. But gender issues remained largely marginalized because many historians presented a "male version of history" (Hill 1996, 12). Oral history accounts of sports fandom in England often excluded or invisibilized women. Football historians have certainly tended to assume that accounts provided by male working-class supporters are the only available means of illuminating and understanding fan cultures in the postwar period (Holt 1992; Fishwick 1989).

[3.2] Feminist academics have challenged this masculinist version of sports history. Langhamer (2000), for example, argues that the preoccupation of historians with certain types of leisure has ignored or misrepresented the experiences of women, and she proposes a more holistic approach to the history of women's leisure. Parratt (2001, 2–3), in her discussion of working-class women's leisure between 1750 and 1914, argues there is a need for an approach to history that "draws women in from the wings and puts them at center stage, that acknowledges that they were historical agents and deserve to be the subjects of historical research." In Wimbush and Talbot's Relative Freedoms (1988), women's leisure experiences have also been brought more to the fore (see also Deem 1986; Green, Hebron, and Woodward 1990). But while research of this kind makes women's leisure experiences more visible, it still largely neglects the experiences of female sports fans. Hargreaves (1994), for example, recognizes how the importance of sports for women has been largely neglected in research, but her own excellent work still focuses primarily on women's experiences of playing sport.

[3.3] A more recent contribution from Lewis (2009) on female spectators in early English professional football (1880–1914) offers a potentially important new direction and illustrates that women do have a history of sports fandom, even if they usually made up only a small minority of the typical sports crowd. The present paper centralizes the historical experiences of female sports fans in England. In doing so, it seeks to supplement the existing literature on sports history regarding gender and leisure. Historical accounts of active female football fans in postwar England are rare, although Watt's (1993) valedictory popular history of the north London club Arsenal's North Bank standing terrace does examine the memories of some female Arsenal supporters. Not only have the experiences of female sports fans been largely invisibilized here, but also the changing demands and the increasing domestic power of women, relatively speaking, have been widely blamed for the declining attendance of some men at English football from the postwar spectator high of 1949.

[3.4] For instance, the historian James Walvin (1994) claims that from the 1950s onward, British women began to exert more control over how men spent their leisure time and money, thus inexorably drawing respectable married men away from active spectator sport. Fishwick (1989) also argued that English football had always encouraged men, collectively, to spend time away from women, and the trend toward more family-based leisure pursuits in Britain in the 1950s coincided with a major decline in English football attendances—aggregate League crowds fell by 11.25 million (around 30 percent) between 1949 and 1962 (Russell 1997; Walvin 2001). It is perhaps a telling aside that the role of women in English sport in this period is often measured by their alleged negative impact on male attendance rather than by any research-based accounts of the actual experiences of active female sports fans of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s.

[3.5] These golden years of English football are usually assumed to have ended in the early 1960s, when crowds start to decline quite rapidly. A popular marker here is when, after a bitter struggle between the sport's employers and the footballer players' union, the constraining maximum wage for football players in England was finally lifted in 1961 (Harding 2009). The term "golden age" often appears in popular and media accounts of the history of English football, and it is certainly clichéd. For example, both hooliganism and stadium safety were clearly underplayed in this period; English football fans were very poorly served by the responses of the authorities to routine instances of the dangers of overcrowding, and they suffered inadequate and badly resourced fan provision as a result (Ward and Williams 2009; Williams 2010). But this label also seems surprisingly appropriate here, not least because of the obvious warmth with which this period is often recalled by older female football fans. Most football players in England at this time still earned plausibly ordinary wages compared to the employed mainstream in Britain, and they mixed regularly and relatively easily with local supporters, partially as a result of this fact. In this sense, professional football players of the time in England were clearly and definitively "class located," in Critcher's (1979) terms. In the late 1940s and for much of the 1950s in Britain, mass car ownership, home-based leisure, the new consumerism, and organized fan hooliganism all lay in English football's uncertain future. The English football professional of the 1950s was a sporting hero known largely to, and embraced by, his local communities for both his character and loyalty; the football player as a truly national or global celebrity, a sports and media star identified mainly by other, more transient, attributes, was generally yet to emerge (Giulianotti 1999).

[3.6] Our subjects for this research come from a wider, comparative semistructured interview study of female rugby union and football fans in a single location, the English East Midlands city of Leicester (Pope 2010). Using systematic sampling techniques, our respondents were originally drawn from existing local sampling frames for the two sports, which had been generated by fan surveys undertaken previously in Leicester (Williams 2003; Williams 2004). They were selected to try to reflect the experiences of different generations of female sports spectators from three distinctive age groupings: 15–30 years (younger fans), 31–50 years (middle-aged fans), and over 51 years (older fans). This produced a total sample of 85 female sports fans who were interviewed. But this paper concentrates on the 16 Leicester City fans who make up the older fan group for football. The original case codes used in the research (F40, F46, etc.) have been utilized to protect participant anonymity; "STH" below means the fan concerned is currently a Leicester City season ticket holder—someone who attends all the club's home matches. At the time of the research, Leicester City was competing in the second tier of English football, but the club routinely attracted more than 20,000 spectators to home games (note 3).

[3.7] The recorded interviews typically lasted between 45 minutes and 2 hours, although some went on for up to 4 hours. They were usually conducted in the homes or the workplaces of our respondents. All were conducted by the female researcher and coauthor of this paper (also a Leicester City fan), who was occasionally challenged in her work by male (usually husband) intrusions or other forms of male "policing" of female research (Deem 1986). This is a further indicator, of course, of the highly marginal role still allocated by some men to some women in the latter's role as sports spectators (Pope 2008). Thus, our findings draw on oral history accounts that explore women's experiences of the so-called golden age of English football in the 1950s and early 1960s. Because of space constraints, we explore just three main themes: English football and a sense of safety; styles of female fan support; and women's relationships with football players.

4. English football and a sense of well-being: "It was safe"

[4.1] Fishwick (1989) describes how Football Association (FA) records show there were only 22 cases of football crowd trouble demanding FA consideration in the years 1948 and 1949, when Football League attendance peaked in England. It is also remarkable that so many millions of people entered what were clearly unpleasant and even dangerous environments each week—crowded postwar football stadia—and yet the vast majority returned unscathed (Walvin 2001; Williams 2010). Moreover, older female football fans describe their relative lack of fear of attending during this period, with some attributing this, on reflection, either to youthful indifference to potential danger—"When you're young, you don't care"—or the idea that any risks involved were acceptable—"All part of the afternoon, the entertainment" (F45, F47). If women (or other fans) ever needed assistance at football matches during this period, they were also protected by the much-mythologized and eponymous postwar British bobby (police officer):

[4.2] It was safe; there was none of this aggression. We didn't have loads of police, just didn't have that, no nastiness, none at all…[But] obviously if you did anything wrong, they'd [the crowd] get the bobby to come and see to you. And everybody was frightened of policemen. Now they're not the least bit [frightened]. (F46, age 73, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as a nurse)

[4.3] This is an idealized picture, of course. But the police presence at football matches—or the relative lack of it—only served to reinforce the notion that, in the main, 1950s English football grounds were regarded as safe spaces for both men and women. For example, F43 remembers the "good times" of attending matches in the years from 1949 with a certain nostalgia when the "policeman would take off his helmet, so you could see [the match]." This is perhaps an especially powerful image, strongly signifying the prehooligan period of relative crowd harmony—though other accounts clearly suggest that male supporter violence was already a subterranean feature of postwar English football culture (Williams 2010).

[4.4] A range of positive terms or phrases were used by female fans to describe their early football experiences, implicitly making comparisons with a more fractious, less tolerant, present: a "friendly atmosphere"; "You never saw any trouble" or heard "bad language"; one never felt "scared," "intimidated," or "afraid" (F40, F43, F45, F46, F47, F50, F51). Johnes and Mellor (2006), similarly, argue that a real sense of national cohesion and togetherness developed around the shared experiences of spectator sport in Britain following the recent privations of World War II. A key moment here perhaps was the live television coverage of the coronation of a new young British queen in 1953 and the first mass TV audience for the so-called Stanley Matthews FA Cup final of the same year. Matthews, the heroic, deferential old England international forward, achieved a life's ambition, to national acclaim, by helping his club Blackpool defeat Lancashire rivals Bolton 4–3 in a coruscating struggle. The early 1950s were also a period of relative national optimism in Britain, when its people assumed the nation would enjoy greater "social solidarity and attain global significance and glory thanks to the Commonwealth" (Johnes and Mellor 2006, 269). In football crowds, this was reflected in rather more prosaic terms:

[4.5] People were more careful about the way they treated each other. You didn't rush along and knock people over, the atmosphere was sort of friendly…And people were more…well, I certainly didn't see any sign of people being rude or aggressive. (F40, age 64, STH, long-term fan, community social worker)

[4.6] Hood and Joyce (1999) have tracked similar sentiments among men and women growing up in London working-class neighborhoods in both the 1930s and 1950s. Their subjects stressed that still-binding structures of family, community, and class solidarity seemed more important and more stable in these periods than they are today. Respondents in our own research seem to share similar ideas about supposed greater communal trust in others, a point perhaps best illustrated when F47 described how large numbers of football supporters were happy to pay local residents threepence to look after their bikes while they watched the match.

[4.7] This was also a period when generational relationships in public are remembered as being experienced rather differently than they are today. A number of respondents, for example, described how they witnessed children being passed down to the front of large football crowds in the early 1950s, over the heads of other crowd members—or how they experienced this themselves (F32, F40, F43, F46, F47, F51). There was little apparent fear that children might be abused, crushed, or lost in these potentially chaotic public contexts. There seems to have been relatively little public concern or panic expressed about relations between children and stranger adults in sports crowds. As F43 recalls:

[4.8] I thought it was very exciting, I mean they were big crowds in those days. I've been down at one time at half past seven in the morning to get on the wall for a cup match […]. We were there early, but if I wasn't you were passed down. If you wanted to go [to the] toilet you were passed up, coz they [the toilets] were at the back (laughs). You made friends and they'd save you a place on the wall, you know? They'd spread out. (F43, age 69, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as a school meals cook)

[4.9] English football culture at this time was also less prescriptive and certainly less profit-focused. Watching football was described as a form of cheap entertainment that would often be combined with dancing in the evening (F45) to complete a Saturday of simple, local leisure pleasures. Football grounds seem to be viewed, broadly speaking, as friendly and safe spaces in this period by female supporters—places characterized by the easy mixing of rival supporters in the stadium. Some respondents suggested that mixing with rival supporters—more difficult today inside segregated stadia—was also an important part of the essential sociability of the event (F48, F49, F51):

[4.10] The atmosphere could be absolutely electric. And both sets of fans were together. I mean, that was part of it: conversing with them. You'd say things like "He's a good player." Or "What's so and so like, I've not seen him play yet?" to other fans. [emphasis added] (F49, age 70, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as a secretary)

[4.11] As well as the term "electric" used here, descriptions such as "buoyed up," "elated," "enjoyable," and "excited" were generally used to describe the tightly packed postwar audiences that, like great creatures, were often remembered as surging forward with the crowd swaying (F45, F47, F49, F51). This sociability and easy familiarity inside football crowds operated across the sexes. One of Watt's (1993, 275) male interviewees described, for example, how male fans at Arsenal used to warm their hands under the arms of unfamiliar females, with no objections. The sense that there was rather more sexual innocence and more mutual trust between the sexes at postwar football was also touched upon by our own respondents. Those older women who were terrace (standing) fans claim not to have been threatened at all by being stationed for hours on end, "body to body" (F50); instead, such corporeal proximity with men helped women keep warm (F47, F50).

[4.12] Social class relations also shaped the football stadium crowd, of course. F50 recalled how, in this period, stadium seating was assumed to be for "the hierarchy"; only a relatively small part of the stadium capacity was made up of seats, and this was where the higher classes, club directors, and shareholders sat—the "posh people" (F47), in other words. Thus, perhaps a more strongly shared class identity added to this greater community spirit and a greater sense of common purpose and solidarity at the stadium, and indeed, to stronger feelings of collective solidarity in British society more generally.

[4.13] This generally friendly match day climate at postwar English football would be challenged, of course, by developments among young male supporters in later decades. Walvin (2001, 156), for example, notes that by the end of the 1960s, fan behavior at football in England was being discussed as a rising social problem, and more serious incidents soon pitched rival groups of male hooligans against each other. Women's experiences at football stadia in the 1970s and 1980s were certainly different from those in the earlier golden age. F40, for example, described how her dad first took her to watch Reading Football Club when she was 13 years old, and she continued to attend matches throughout the 1950s and 1960s, before moving to Leicester in the 1970s. Here, experience of male fan violence meant she would soon resort to watching sport on television:

[4.14] Going home after the match there would be really running street battles almost with crowds like surging forward, and things being thrown […]. I was frightened of a bottle on the back of the head really you know, stuff was being lobbed about the streets, it was really quite awful […]. I never saw any of that when I was a child certainly…you just mixed in you know? It didn't matter who […]. I thought well why am I putting myself through this? Being frightened to go somewhere…And I just stopped going. (F40, age 64, STH, long-term fan, community social worker)

[4.15] Other respondents who continued to attend during this period also recalled instances when they were fearful for their own safety. This fan violence would indeed represent the end for some of the modernist optimism and collective solidarities at sport of the golden age.

5. Styles of support: "Everybody was in tune"

[5.1] Exactly how did women support their sports clubs during this period? Some sense of the carnivalesque and a rejection of the banality and anonymity of everyday life are clearly apparent. Turbin (2003, 45) argues that dress is highly gendered and that clothing gives both shape and meaning to the bodies of men and women. Dress is inherently both public and private, as "an individual's outwardly presented signs of internal or private meaning are significant only when they are also social, that is comprehensible on some level to observers." Some of our respondents discussed their own match day football costumes, outfits they had made or purchased especially for this purpose. These seemed to be important for individual (private) identities and for exhibiting a public face for their fandom. For example, F47 described her public parading of Leicester City's blue and white colors for the 1949 FA Cup final while traveling with a female friend:

[5.2] We were teenagers and we dressed alike…And we had this whitish coat with a belt round. We had royal blue trousers […] and we had head scarves, I had them made on the market […]. We thought it was very smart…and, you know, the thing of the moment. We were—we're somebody; we're on the bus and we're going to Wembley. (F47, age 78, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked in sewing)

[5.3] FA Cup Finals—the culmination of the English football season and the most historically important domestic knockout football tournament in the world—were very special community occasions in this era, a welcome opportunity for the demonstration of local female craft and for ostentatious public display in a generally gray public arena. The FA Cup seemed to demand more expressive forms of local support, and we can perhaps speculate that this opportunity for public display may have been even more important to female fans. This was an era before the mass production of football replica kits and goods, so outfits were original—individualized and designed by fans. F49 described how she prepared her costume for weeks prior to the final, and that she would even wear her outfit to work to seek the approval and opinions of her colleagues. Dressing up for football may also have been a way of seeking male fan approval, a publicly legitimated way for females to express both their (hetero)sexuality and their support and club and civic loyalty. F47 remembers receiving compliments for her final costume from the male fan group she stood alongside at matches. F38, and three other young women from Leicester, wore their outfits to all home and away matches, including the 1963 FA Cup final:

[5.4] F38: We'd be the only girls on the train. Oh, it used to be fabulous (laughs). We used to have white skirts, royal blue tops, white shoes…I mean, white shoes to a football match! But that's how it was (laughs). [And] blue and white scarves…we all wore the same hair; hair all up here. We must have looked a sight!

Res: Did you get much attention from men then?

F38: Oh yes, yes! Wonderful! (laughs)

(F38, age 60, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as a clerical worker)

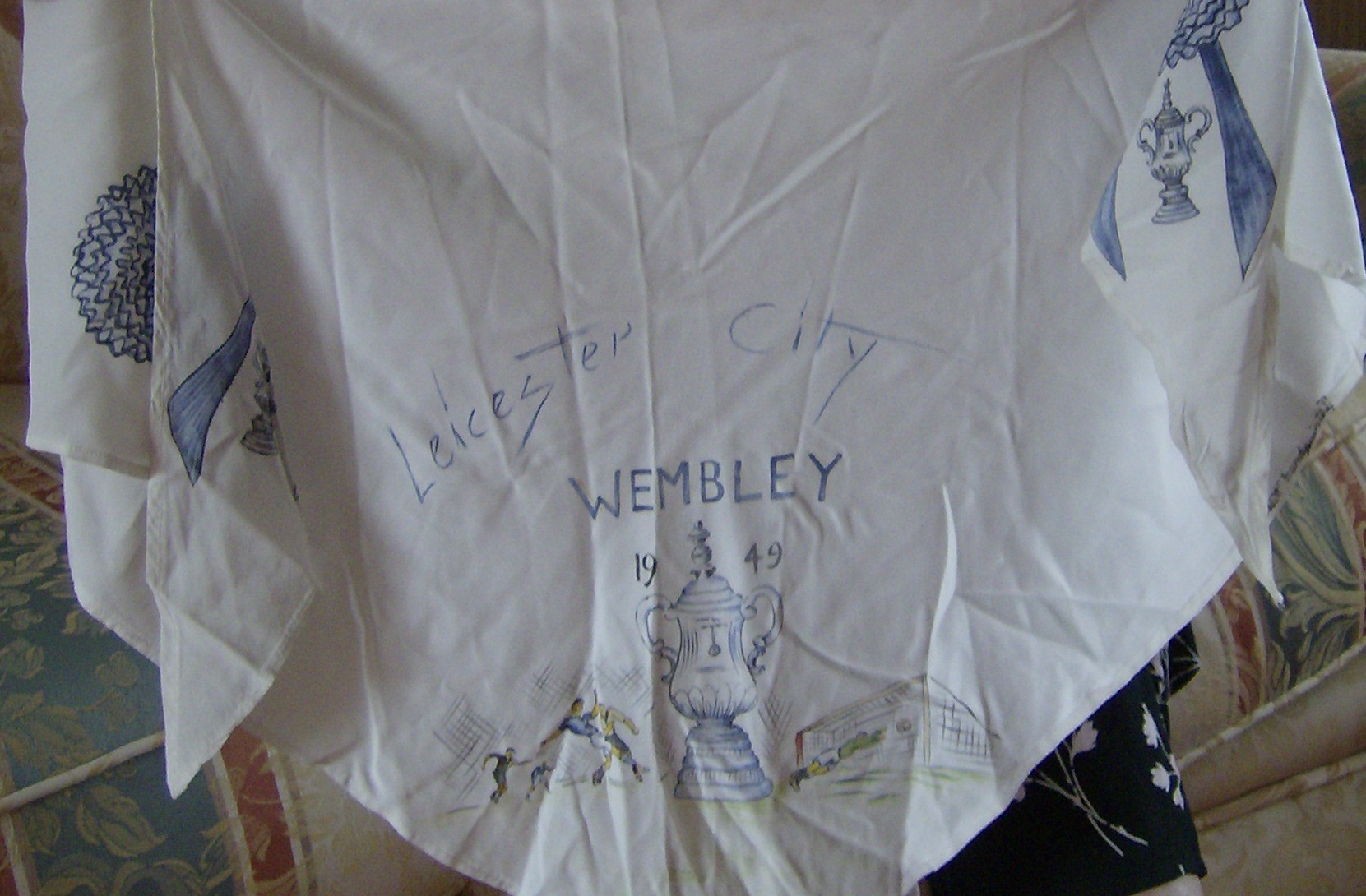

[5.5] The figures included here demonstrate the importance of fan memorabilia for our older sample of female fans. Figure 1 shows a football head scarf made at the local hosiery market in Leicester for one of our subjects. Players from Leicester City and Wolverhampton Wanderers are hand painted on it for the 1949 FA Cup Final. Figure 2 shows a cabinet at the home of one of our respondents. It contains football products, including a number of foxes (Leicester City's club logo and nickname). Many female fans had football photographs on the walls of their homes, including shots taken with players from previous decades. Some had also decorated parts of their homes in Leicester City blue.

Figure 1. Fan's head scarf painted for 1949 FA Cup Final. [View larger image.]

Figure 2. Fan's display cabinet with "Foxes" memorabilia. [View larger image.]

[5.6] After losing the 1953 Matthews FA Cup final, the mayor of Bolton praised the club's players for promoting and adding luster to the town (Johnes and Mellor 2006, 267). A local football club reaching the FA Cup final at this time contributed to a palpable sense of civic pride and a strengthening of local communal identities for both men and women of the city. It generated a sense of community affiliation that affected female supporters as much as it did men—though relatively few fans, male or female, had the opportunity to attend the final because of restrictive FA ticketing policies. F38 described how "tickets were few and far between" for FA Cup finals, but also noted that such matches engaged not only active football fans, but the city as a whole:

[5.7] You could go in the shops; they'd got flags up, even in the little villages, "Good luck City." It was the community, this is what I mean. It makes the whole city, because you'd walk round Leicester all trimmed up blue and white. Oh it was a wonderful sight to see […]. It was great; it was good for the city, good for the city of Leicester, because everybody was in tune. (F49, age 70, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as a secretary)

[5.8] The image of the English football stadium of the 1940s and 1950s as a safe—if highly masculinized—public space was expressed very strongly by those who confirmed that women were a distinct minority at matches in these early postwar years (F36, F37, F38, F40, F47, F51). But some female attendees also found the sheer numbers and habits of men intimidating. For instance, F36 went to one football match as a child but then was deterred from attending by the large numbers of men present who were smoking; she did not return to the stadium until the late 1990s. This oppressive, smoky atmosphere was mentioned by other older female fans (F37, F47). Of the 11 older fans who regularly attended matches during these years, a number attended at some stage (usually as teenagers) in all-female groups (F38, F43, F47, F49).

[5.9] But gender also presented some special privileges in the stadium—improved access to star players, and being chaperoned and generally protected by chauvinistic men. For example, F40 described how, because hardly any of her female friends went to football, she enjoyed some local distinction. She could boast to female friends, "Oh, I saw him. Oh and he's so handsome, this man. This footballer." Others discussed how, as teenagers attending matches in 1940s and 1950s, they had player favorites (F40, F43, F45, F46, F47, F49, F50) and some stayed behind with other female fans after games to collect player autographs. Players, it seems—even modernist and modest class-located, postwar sporting heroes—had something of a sexual aura surrounding them, although the typical profile and lifestyle of the English professional football player has changed dramatically since.

6. Women's relationships with football players: "They were just like one of us"

[6.1] First team football players in England were lauded in the 1940s and 1950s, but they were also strongly located in the local community (Critcher 1979). They could be met by fans at the local food market, in shops, or at one's place of work; some women fans had relatives who were friends with players (F45, F50, F51). There was a strong sense that players were "Leicester people" who would typically walk to the home ground along with everyone else on a match day (F49). Terms such as "approachable," "closer," "one of us," and "ordinary guys" who lived in "ordinary houses" (F37, F40, F43, F46, F47) were frequently used when discussing players of this period.

[6.2] A number of older respondents either lived near Leicester City players or knew people who did; players were a part of the local working-class or lower-middle-class communities of the city (F25, F39, F40, F43, F46). Some recalled seeing players socially after important matches. F39 remembered how her pub-owning parents gave lodgings to a Sunderland player who was on loan at City in the 1950s; lodging a football player was no great social marker at the time. F43 even described how, later, the Leicester City and 1966 England World Cup–winning goalkeeper Gordon Banks had living and child care arrangements in Leicester, which meant that he maintained strong daily connections with ordinary women's lives, including mixing regularly with local mothers:

[6.3] I used to take her [daughter] to school, and I used to walk with Gordon Banks when he took his chap to school. […] He was just in an ordinary semi-detached house up the road near the school, and mixed with all the mothers. [Be]cause there weren't that many men that took the children to school. He was a very nice chap. (F43, age 69, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as school meals cook)

[6.4] Thus, women fans in the city may have been in awe of footballers to a degree, but because players mixed locally and were not earning wages that were notably superior to many other local people in professional jobs, they were socially and culturally located; they did not "think they were up on a pedestal like some [players] do now" (F37). Football players today were seen as being more "cut off" because they live separately from fans, in "big mansions" (F40, F43). Holt and Mason (2000, 122), commenting on football culture in the 1950s, similarly suggest that "This was a world where local heroes were still ordinary men. Great players were often seen on the street or in the pub." Some players in England had part-time jobs in addition to playing football professionally; and despite attendance increasing after World War II, the existence of a maximum wage meant that most players did not benefit from this rise in club income (Walvin 2001). Players may have been "football slaves" in this period (Russell 1997, 92), but their modest earnings offered a greater "moral sense" to their established position as engaged and located figures in the local community (F19, F29, F30, F36, F37, F40, F45, F46, F49, F51).

[6.5] Older female respondents fondly remember this era, partly because of the imagined greater sense of stability, but also because—perhaps less likely today—football was perceived to be an important local site for the expression of local belonging as well as national virtues. These were often defined, in part, by a sense of certainty about local traditions and place and cultural continuity: a social homogeneity and a common ethnicity. In today's more global game, Leicester City, like most English football clubs, recruits players from around the world. This new direction for football was rather more difficult for some respondents to identify with and accept:

[6.6] I'm a big believer in local talent […]. I mean in Leicester City now—don't get me wrong, I'm not racist—but you've got nine "internationals," I'll call them, in that team and probably two or three white players. None of them are from Leicester, probably. Are they going to be loyal to Leicester City as a club? […]. Their loyalty is probably with their salary. They think "I'll play for Leicester but I don't live here, I've got no interest in the city, I don't care." (F36, age 68, occasional attendee, new fan, retired, worked as a secretary)

[6.7] In this sense, local (white) players of the past were generally deemed to have been more dedicated to local clubs, and hence fans got "better value for money" from them, compared to the more transient and wage-focused football professionals of today (F19, F36, F40, F45, F46, F49). Today's superstars are detached and are "not really hungry enough for the game" (F40). Because their loyalty is market-driven—strictly to the best payer—they do not show the same levels of attachment, commitment, and physical effort—a willingness to "die for the shirt"—as players of the golden age once did:

[6.8] It was football [then], it isn't today…It was better then, because they were working hard and they weren't just thinking about the money […]. They were all good players in those days, as I say. They'd got to play good otherwise they wouldn't get the money. But now they get the money anyway, it doesn't matter whether they earn it or not. (F45, age 80, STH, long-term fan, retired, worked as a personal assistant)

[6.9] It seems like a long time ago now; the changes are fairly subtle all the way through. But it's gone, from ordinary working class lads who kicked a ball about, who lived in the community, to players that are no longer part of our community, but belong to their own. (F40, age 64, STH, long-term fan, community social worker)

7. Some conclusions

[7.1] The recollections and views expressed above are, of course, partly couched in nostalgic reflection, and sometimes dimmed by memory. Social and economic change—the impact of globalization—is difficult to accept, perhaps especially as one gets older and, arguably, more conservative. Were all football players in England of the 1950s really "class located" and as committed to their clubs and local supporters as is suggested here? Do all foreign players today lack the commitment that is somehow deemed as being more inherent in locals? This seems doubtful. But these comments, we assert, reveal wider discomforts and anxieties about the neoliberal sports and economic order of today—about the perceived "chaos of reward" of Jock Young's (1999) disorienting late-modern world. Here, the widely held perception seems to be that society today is less obviously fair and meritocratic, and that showing loyalty and working hard—in any sport, business, or company—is no longer a guarantee of just rewards and opportunities as perhaps it once was. Players of this golden era of football are thus idealized for their supposed love of the game, and for their more visceral connections with a people and an occupation that was "their hobby, as well as their sport and their profession" (F49).

[7.2] The probably mistaken idea expressed by some respondents that "there were no super heroes years ago; they all played as a team" (F43) also echoes Phelps's (2001, 47) suggestion that the ethos of the "starless" southern Portsmouth championship winning teams in England of seasons 1948–49 and 1949–50 embodied the same sense of player commitment and industriousness that was so widely admired then in the working-class cities of the English North and Midlands. Richard Holt (1992) has suggested that English football is rooted in working-class traditions of collective endeavor. Playing football provided male factory workers of the 19th and 20th centuries with a sense of release, belonging, and solidarity. The capacity to work hard, take punishment, and play your role in the team—all features of manual work—were the qualities the working-class male sports crowd most admired.

[7.3] Thus, the male working classes in England identified strongly with football because it seemed to reflect a working-class experience back to them. The division of labor within a team could be compared to the "specialization of skills that went into the production of iron and steel or, perhaps more appropriately, the manufacturing of machinery" (Holt 1992, 162–63). Our own interviewees—like those of Phelps (2001)—also confirm that the key qualities admired in players of this period included a sense of fair play and a gentlemen's reputation for being reserved; for showing courage, and exhibiting heroic forms of traditional working-class loyalty and toughness. Thus, it seems that female fans also identified strongly with traits more typically associated with English identity and masculinity. While some of our female fans recalled identifying strongly with individual players, there was little room in supporters' affections—male or female—for fancy Dans or faint hearts. In many ways, such sentiments endure in England today.

[7.4] In more recent times, it can be contested that women have a slightly more respected role as fans in the game. It has been suggested that football fandom in England (following the changes in the sport after 1989) has become more "feminized" (Crolley and Long 2001). Changes such as the introduction of all-seater stadia contributed to the so-called post–hooligan era in football in England, producing a safer and more civilized environment at matches (Williams 2006). This may have led to some female (and male) fans returning to the sport or being newly recruited as fans—recent surveys have shown that the average number of female fans at Premier League matches has steadily increased, and is now around 15 percent of all fans (Williams 2001b). Yet rather than offering a serious discussion of women as knowledgeable, committed fans, the research focus in football often remains on women in subordinate or sexualized roles or both. For writers such as Clayton and Harris (2004), this might be seen as an encouraging sign of the postmodern era in the sense that women are visible at all in the sporting culture, but there is clearly a long way to go if women's role in football, as fans, players, administrators, officials, and so on, is to be taken seriously.

[7.5] Our findings here offer but a brief historical snapshot of women's experiences of English football's golden age. We have concentrated on their perceptions of football crowds, on styles of female support, on local identities framed through sport, and on their relations with, and perceptions of, football players from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. We contend that women fans have been largely ignored by male sociologists and historians in their accounts of the cultural and social significance and meaning of football. The oral history research presented here can make some claims to try to "retrieve" the experiences of women fans in this context and to explore, in some greater depth, the various ways in which women once connected with the sport in both its production and consumption. This was before wider social changes from the late 1960s onward—including male fan hooliganism—began to offer new challenges to the role of women as active fans at English football matches.

8. Acknowledgment

[8.1] This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (grant PTA-030-2005-00310).

9. Notes

1. In 1985, at the European Cup final between Liverpool and Juventus at the Heysel Stadium, Brussels, Liverpool supporters broke into a section of the stadium containing Italian fans; in the ensuing panic, 39 supporters died following a wall collapse. In addition to the action of English fans, the European football governing body UEFA and also the Belgian authorities were widely criticized for the poor state of the stadium and the inadequate control exercised at the venue. As a result of these incidents, English football clubs were banned from playing abroad, an exclusion that lasted 5 years, with an additional year for Liverpool FC (Williams 2010, chap. 17).

2. The Hillsborough Stadium disaster occurred on April 15, 1989, during an FA Cup semifinal between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest at Sheffield's football ground, Hillsborough. Holt and Mason (2000, 159) discuss how the match was abandoned shortly after the start, when overcrowding on the terraces led to Liverpool supporters being crushed against perimeter fencing. Ninety-six people died and many more were injured. The tragedy was primarily the result of police mismanagement of the crowd; it led to the British government commissioning Lord Justice Taylor to investigate the causes of the accident. The Taylor Report of 1990 made 76 recommendations—most of which were implemented—including the removal of all perimeter fencing; the elimination of standing accommodation by August 1994 from the grounds of all clubs in the top two divisions in England and Wales and the top division in Scotland; and the establishment of a football licensing authority with statutory powers, which would inspect grounds and give out safety licenses (Williams 2010, chap. 17).

3. Leicester City FC currently (2010–11) competes in the Championship, the second tier of English football, and was playing at this level while the research was being undertaken. For many of the years following World War II and into the 1950s, the club competed at the second level of English football (Division Two), but between 1957 and 1969, Leicester City enjoyed its longest-ever unbroken period in topflight football (Division One). Thus, in the period our respondents are discussing, the club was fairly successful, and made four losing FA Cup Final appearances, in 1949, 1961, 1963, 1969. After its relegation in 2004, the club has aspired to return to topflight English football, the Premier League.

10. Works cited

Allison, Lincoln. 1981. Condition of England: Essays and Impressions. London: Junction Books.

Bale, John. 1993 Sport, Space and the City. Caldwell, NJ: Blackburn Press.

Cere, Rinella. 2003. "'Witches of Our Age': Women Ultras, Italian Football and the Media." In Sport, Media, Culture: Global and Local Dimensions, ed. Alina Bernstein and Neil Blain, 166–88. London: Frank Cass.

Chen, Po-Ju. 2010. "Differences between Male and Female Sport Event Tourists: A Qualitative Study." International Journal of Hospitality Management 29:277–90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2009.10.007.

Clark, John S., Artemisia Apostolopouloua, and James M. Gladden. 2009. "Real Women Watch Football: Gender Differences in the Consumption of the NFL Super Bowl Broadcast." Journal of Promotion Management 15:165–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10496490902837510.

Clayton, Ben, and John Harris. 2004. "Footballers' Wives: The Role of the Soccer Player's Partner in the Construction of Idealized Masculinity." Soccer and Society 5 (3): 317–35.

Conn, David. 1997. The Football Business: Fair Game in the 1990s? Edinburgh: Mainstream Press.

Crawford, Garry, and Victoria K. Gosling. 2004. "The Myth of the 'Puck Bunny': Female Fans and Men's Ice Hockey." Sociology 38 (3): 477–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0038038504043214.

Critcher, Chas. 1979. "Football since the War." In Working-Class Culture: Studies in History and Theory, ed. John Clark, Chas Critcher, and Richard Johnson, 161–84. London: Hutchison.

Crolley, Liz, and Cathy Long. 2001. "Sitting Pretty? Women and Football in Liverpool." In Passing Rhythms: Liverpool FC and the Transformation of Football, ed. John Williams, Stephen Hopkins, and Cathy Long, 195–214. Oxford: Berg.

Deem, Rosemary. 1986. All Work and No Play? The Sociology of Women's Leisure. Milton Keynes: Open Univ. Press.

Dunning, Eric, Patrick Murphy, and John Williams. 1988. The Roots of Football Hooliganism: An Historical and Sociological Study. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Dunning, Eric, John Williams, and Patrick Murphy. 1984. Hooligans Abroad. London: Routledge.

Fishwick, Nicholas. 1989. English Football and Society, 1910–1950. London: Sportsman's Book Club.

Foot, John. 2006. Calcio: A History of Italian Football. London: Fourth Estate.

Funk, Daniel C., Lynn Ridinger, and Anita J. Moorman. 2004. "Exploring Origins of Involvement: Understanding the Relationship between Consumer Motives and Involvement with Professional Sport Teams." Leisure Sciences 26 (1): 35–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01490400490272440.

Giulianotti, Richard. 1999. Football: A Sociology of the Global Game. Cambridge: Polity.

Green, Eileen, Sandra Hebron, and Diana Woodward. 1990. Women's Leisure, What Leisure? London: Macmillan Education.

Harding, John. 2009. Behind the Glory: 100 Years of the PFA. Derby: Breedon Books.

Hargreaves, Jennifer. 1994. Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of Women's Sports. London: Routledge.

Hill, Jeffrey. 1996. "British Sports History: A Post-modern Future?" Journal of Sport History 23 (1): 1–19.

Holt, Richard. 1986. "Working-Class Football and the City: The Problem of Continuity." British Journal of Sports History 3 (1): 5–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02649378608713586.

Holt, Richard, ed. 1990. Sport and the Working Class in Modern Britain. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press.

Holt, Richard. 1992. Sport and the British: A Modern History. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Holt, Richard, and Tony Mason. 2000. Sport in Britain, 1945–2000. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hood, Roger, and Kate Joyce. 1999. "Three Generations: Oral Testimonies on Crime and Social Change in London's East End." British Journal of Criminology 39 (1): 136–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjc/39.1.136.

Johnes, Martin, and Gavin Mellor. 2006. "The 1953 FA Cup Final: Modernity and Tradition in British Culture." Contemporary British History 20 (2): 263–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13619460600600847.

Jones, Katherine W. 2008. "Female Fandom: Identity, Sexism, and Men's Professional Football in England." Sociology of Sport Journal 25 (4): 516–37.

Jones, Stephen G. 1986. Workers at Play: A Social and Economic History of Leisure, 1918–39. London: Routledge.

Jones, Stephen G. 1988. Sport, Politics, and the Working Class: Organised Labour and Sport in Interwar Britain. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press.

Kim, Hyun Mee. 2004. "Feminization of the 2002 World Cup and Women's Fandom." Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 5 (1): 42–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1464937042000196806.

King, Anthony. 2002. The End of the Terraces. London: Leicester Univ. Press.

Kynaston, David. 2009. Family Britain, 1951–57. London: Bloomsbury.

Langhamer, Claire. 2000. Women's Leisure in England, 1920–60. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press.

Lewis, Rob. 2009. "'Our Lady Specialists at Pikes Lane': Female Spectators in Early English Professional Football, 1880–1914." International Journal of the History of Sport 26 (15): 2161–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09523360903367651.

Llopis Goig, Ramón. 2007. "Female Football Supporters' Communities in Spain: A Focus on Women's Peñas." In Women, Football and Europe, ed. Graham Baldwin, Kevin Moore, and Jonathan Magee. Oxford: Meyer & Meyer Sport.

Mellor, Gavin. 1999. "The Social and Geographical Makeup of Football Crowds in the North-west of England, 1946–1962: 'Super-Clubs,' Local Loyalty, and Regional Identities." Sports Historian 19 (2): 25–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17460269909445818.

Nash, Rex. 2000. "Contestation in Modern English Professional Football: The Independent Supporters Association Movement." International Review for the Sociology of Sport 35 (4): 465–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/101269000035004002.

Nash, Rex. 2001. "English Football Fan Groups in the 1990s: Class, Representation and Fan Power." Soccer and Society 2 (1): 39–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/714866720.

Parratt, Catriona M. 2001. "More than Mere Amusement": Working-Class Women's Leisure in England, 1750–1914. Boston: Northeastern Univ. Press.

Phelps, Nicholas A. 2001. "The Southern Football Hero and the Shaping of Local and Regional Identity in the South of England." Soccer and Society 2 (3): 44–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/714004861.

Phelps, Nicholas A. 2005. "Professional Football and Local Identity in the 'Golden Age': Portsmouth in the Mid-Twentieth Century." Urban History 32 (3): 459–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S096392680500324X.

Pope. Stacey. 2008. "Out in the Field." Sociology Review 17 (4): 14–16.

Pope, Stacey. 2010. "Female Fandom in an English 'Sports City': A Sociological Study of Female Spectating and Consumption Around Sport." PhD thesis, Leicester: Univ. of Leicester. Available at Leicester Research Archive, https://lra.le.ac.uk/handle/2381/8343.

Robinson, Matt, and Galen T. Trail. 2005. "Relationships among Spectator Gender, Motives, Points of Attachment, and Sport Preference." Journal of Sport Management 19 (1): 58–80.

Russell, David. 1997. Football and the English: A Social History of Association Football in England, 1863–1995. Preston: Carnegie.

Sandvoss, Cornel. 2003. A Game of Two Halves: Football, Television and Globalisation. London: Routledge.

Smith, Aaron C. T., and Bob Stewart. 2007. "The Travelling Fan: Understanding the Mechanisms of Sport Fan Consumption in a Sport Tourism Setting." Journal of Sport and Tourism 12 (3–4): 155–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14775080701736924.

Taylor, Ian. 1987. "Putting the Boot into a Working-Class Sport: British Soccer after Bradford and Brussels." Sociology of Sport Journal 4 (2): 171–91.

Taylor, Ian. 1991. "English Football in the 1990s: Taking Hillsborough Seriously?" In British Football and Social Change: Getting into Europe, ed. John Williams and Stephen Wagg, 3–24. Leicester: Leicester Univ. Press.

Taylor, Matthew. 2008. The Association Game: A History of British Football. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Turbin, Carole. 2003. "Refashioning the Concept of Public/Private: Lessons from Dress Studies." Journal of Women's History 15 (1): 43–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2003.0038.

Walvin, James. 1994. The People's Game: The History of Football Revisited. Edinburgh: Mainstream.

Walvin, James. 2001. The Only Game: Football in Our Times. Harlow: Longman.

Wann, Daniel L., Merrill J. Melnick, Gordon W. Russell, and Dale G. Pease. 2001. Sport Fans: The Psychology and Social Impact of Spectators. London: Routledge.

Ward, Andrew, and John Williams. 2009. Football Nation: Sixty Years of the Beautiful Game. London: Bloomsbury.

Watt, Tom. 1993. The End: 80 Years of Life on the Terraces. Edinburgh: Mainstream.

Williams, John. 1999. Is It All Over? Can Football Survive the Premier League? Reading: South Street Press.

Williams, John. 2001a. "Who You Calling a Hooligan?" In Hooligan Wars: Causes and Effects of Football Violence. ed. Mark Perryman, 37–53. Edinburgh: Mainstream Press.

Williams, John. 2001b. FA Premier League Fan Survey 2000. Leicester: Univ. of Leicester.

Williams, John. 2003. A National Survey of Premiership Rugby Fans. Leicester: Univ. of Leicester.

Williams, John. 2004. A Survey of Leicester City Football Fans. Leicester: Univ. of Leicester.

Williams, John. 2006. "'Protect me from what I want': Football Fandom, Celebrity Cultures and 'New' Football in England." Soccer and Society 7 (1): 96–114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14660970500355637.

Williams, John. 2010. Red Men: Liverpool Football Club, the Biography. Edinburgh: Mainstream.

Williams, John, and Sean Perkins. 1998. "Ticket Pricing, Football Business, and 'Excluded' Football Fans: Research on the 'New Economics' of Football Match Attendance in England." In A Report to the Football Task Force, ed. Sir Norman Chester Centre for Football Research. Leicester: Univ. of Leicester.

Wimbush, Erica, and Margaret Talbot, eds. 1988. Relative Freedoms: Women and Leisure. Milton Keynes: Open Univ. Press.

Young, Jock. 1999. The Exclusive Society. London: Sage.