1. Introduction: Blurring the fan-musician boundary in early-1960s Hamburg

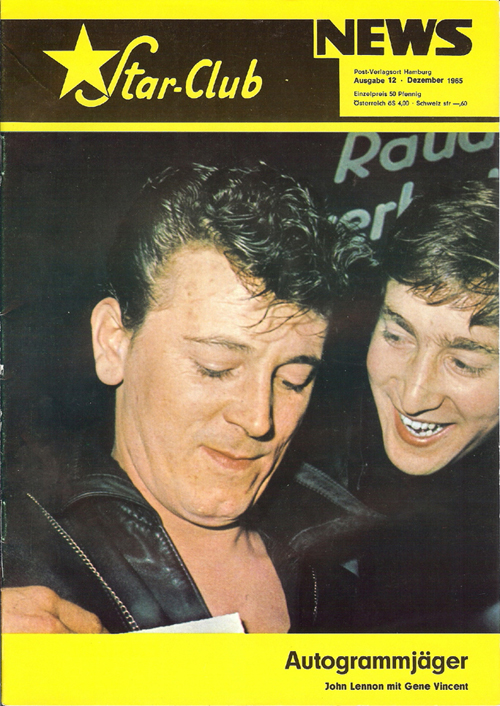

[1.1] The December 1965 cover of the Star-Club News features a photograph of John Lennon and Gene Vincent, bearing the caption "Autograph Hound" (figure 1). The picture was taken in 1962 when Vincent and Lennon's Beatles shared the bill at Hamburg's Star Club, long before the word Beatlemania had crossed anyone's lips. It shows Vincent signing autographs while Lennon looks on with delight. The framing leaves no doubt that when this picture was taken, Vincent was the focus, a rock pioneer enjoying a resurgence in Europe and the kind of big-name performer the Star Club showcased in its drive to become Germany's premier destination for live rock and roll. Lennon is off to the side, just one of many young British rockers slogging away on Hamburg's stages, hungry for a shot at the big time. By the time this image was published in 1965, however, it contained a raft of new meanings. Now Lennon was the star while Vincent's career had been derailed by alcoholism and changing tastes. The caption "Autograph Hound" comments on this improbable role reversal, and it also does something else: it celebrates the role of music fans by pointing out that even a leader of the world's most popular band was once just another giddy admirer angling to get close to his own idol. The message is profoundly egalitarian: fans and musicians appear as equally important members of the scene around Beat music, as rock and roll was rechristened in 1960s Europe.

Figure 1. Star-Club News, December 1965. [View larger image.]

[1.2] Using this image as a starting point, this article explores the close relationship between fans and musicians in Hamburg's Beat music scene in the early 1960s—a scene that not only produced the Beatles but also elevated fans to the status of collaborators in a movement that over the long term helped transform popular culture and society. Hamburg's early rock-and-roll community emerged in a unique spatial context, in clubs around the Reeperbahn, the city's entertainment quarter and red-light district. These clubs erased the distance between performer and audience: fans could press the flesh with musicians as they played onstage or drank with the crowd, and they also experienced this scene bodily through dancing or sexual encounters. The timing of this scene's emergence is also significant: it appeared during a new phase of capitalist modernity after 1960 that granted youth (defined here as those born during or just after World War II, roughly 1939 through 1950) unprecedented access to commercial venues catering to their new economic power and leisure. Teens and "twens" (people in their 20s) in many classes, regions, and countries used these spaces free of parental supervision to create moments of utopia that offered respite—even if only temporarily—from the postwar era's stifling sexual conservatism and social conformism (Herzog 2005, 101–28). Their voices also emerged through Germany's first rock magazine, the Star-Club News. The Star Club's proprietor became an ally of the fans who made up this musical "nation," keeping prices low so that they could afford to come daily—and hundreds did, forming networks that still exist today. While these fans were not formally organized or overtly oppositional—and hence did not constitute a subculture, as the term has come to be used—the ways they deployed musical and material objects, as well as the ways they asserted their right to public space, made them important agents in West Germany's transition to a more open, democratic society in the 1960s.

2. "Take a seat or piss off!" Experiencing rock and roll in Hamburg

[2.1] For a brief moment in the early 1960s, Hamburg was at the epicenter of Western pop culture, nurturing a sound that Beatlemania made famous the world over. This sound originated at a time when rock and roll was moldering in its native land: newly discharged Sergeant Elvis Presley was off to Hollywood, while other rockers were beset by scandal or elbowed off the charts by crooners and vocal groups. The British kept the beat alive in the form of skiffle, an easy-to-play hybrid of rock and country that induced legions of boys and girls to pick up instruments in the late 1950s. Those with talent formed serious bands that needed places to play, which were in short supply in Britain. Enter Hamburg, a bustling port with long-standing connections to Britain and a booming entertainment economy constantly seeking fresh talent.

Figure 2. Map of Great Britain and North Germany. [View larger image.]

[2.2] Hamburg is West Germany's largest city, a northern city with long traditions of independence and tolerance (figure 2). Shipping and, after 1945, media were the key sources of its prosperity, with the port serving both as Germany's "gateway to the world" and as a source of cosmopolitan influences from across the globe. During the postwar occupation the city found itself in the British zone, and British NATO troops maintained their presence after 1949. Along with shipping, Hamburg is best known internationally for its entertainment district, which was (and still is) located in the portside district of St. Pauli and centered on the spectacular mile known as the Reeperbahn, immortalized in the 1962 film Mondo Cane as an outpost of primitive hedonism (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYDz7onjG9k). Since the 18th century, entertainments high and low have nestled here in Europe's most notorious red-light district. By 1945 the area had survived cholera, strikes, blockades, Allied bombing, and Nazi rule, emerging battered but ready to resume its place as "the anchorage of joy" (der Ankerplatz der Freude). The 1950s saw an explosion in the Reeperbahn's popularity as postwar privations receded and the Economic Miracle brought record numbers of Germans and other tourists seeking amusement. While West Germany in this period, governed by conservative Catholic chancellor Konrad Adenauer, was marked by an official emphasis on hard work and the disgraced nation's return to respectability, the Reeperbahn served as the nation's id, a licentious outpost in Germany's most liberal city (note 1). Punters went there to drink themselves silly in its faux-Bavarian beer halls, watch topless "beauty dancers" in its cabarets, and gawk at mud-wrestling Amazons in its nightclubs. Striptease and open prostitution attracted curiosity-seekers male and female, gay and straight, black and white (Sneeringer 2009). Before the jukebox became ubiquitous, live music provided the soundtrack to this human carnival, in the forms of swing and Dixieland (or "trad") jazz. When rock and roll hit Germany, it was only logical that it too would appear on the menu of entertainment offerings.

[2.3] But rock and roll's entry into Hamburg, and Germany at large, was not a smooth one. It was imported by American and British soldiers, films like Blackboard Jungle (1955), and returning German sailors. In 1956 Bill Haley's "Rock around the Clock" electrified listeners on both sides of the Iron Curtain and Elvis made the cover of Der Spiegel, West Germany's version of Time (http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-43064913.html). Rock and roll captivated a segment of the youth market, though its leering sexuality and menacing aura horrified parents, preachers, and politicians. Between 1956 and 1958 violence punctuated rock-related movie showings, while Haley's concerts ended with smashed seats and dozens of arrests (Poiger 2000; Grotum 1994). German broadcasters resolved to keep this "degenerate" noise off the airwaves. Only Chris Howland was allowed to spin British and American chart-toppers for an hour each week on Nordwestdeutsche Rundfunk's "Saturday Club"; rock on television would have to wait until 1965 and "Beat Club." The music industry served up bland substitutes like Peter Krauss, while American-made rock remained a minority taste confined largely to working-class youths. Resourceful fans could catch snatches of their music on the American Forces Network, British Forces radio in the north, or late at night on Radio Luxembourg, Europe's first commercial pop station. Achim Reichel, a Hamburg teen who became lead singer of the Rattles, pestered his parents for a cassette recorder so he could tape songs directly off the radio; such tapes became primers for a generation of German musicians. Fans in Hamburg could sometimes find rock on the jukebox of their local pub if they lived in working-class St. Pauli or Barmbek, and it was sometimes pumped onto the carnival midway at the Dom. But few such records were available for purchase in the late 1950s and early 1960s; those that were became precious objects circulated among aficionados (Siegfried 2003, 86; Kursawe 2004, 322; Nichols 1983; Krüger and Pelc 2006, 136; Fascher 2006, 65–67, 84–85; Articus 1996, 111; interview with Ulf Krüger, December 2008).

[2.4] Ultimately it was Hamburg's entertainment economy and its voracious appetite for novelty that spurred German venues outside of US military bases (which were generally off limits to civilians) to regularly feature live rock and roll. Enterprising club owners realized there was money to be made in showcasing this style, which was, after all, dance music (and thirsty dancers bought more drinks). Starting in the late 1950s Dutch-Indonesian show bands brought a version of rock to nightclubs like the Blauer Peter, playing Ventures-style instrumentals with a South Pacific accent (Mutsaers 1990). These "Indorockers" were soon replaced by acts from England that, as Ulf Krüger, a chronicler of the Hamburg scene, put it, were "cheaper, rawer, and wilder" (Articus 1996, 19). Cheap, raw, and wild fit perfectly with the ethos of the Reeperbahn itself.

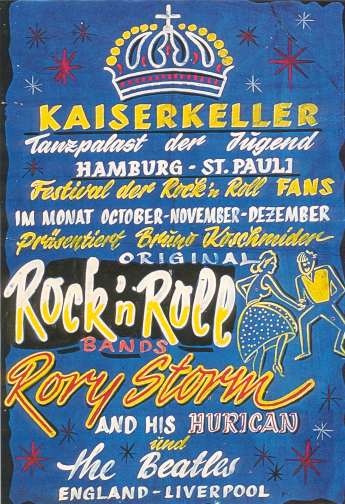

[2.5] The first club to feature live rock and roll for German audiences was the Kaiserkeller, situated in a Reeperbahn side street, the Grosse Freiheit—literally, "great freedom." The location was fitting: the Grosse Freiheit had long housed a rougher breed of entertainment, such as bawdy transvestite revues, than the more brightly lit Reeperbahn. The Kaiserkeller sat at number 36 in a building constructed in 1958 as a three-story "dance palace" complete with a 200-car parking garage (a sign of the emerging car culture). The main floors contained the respectable Lido, which featured ballroom dancing to live orchestras and the occasional "Miss Pullover" contest for added sex appeal; the Kaiserkeller, which opened in October 1959, was relegated to the basement (note 2). Its owner was Bruno Koschmider, a gay former circus clown who landed after the war in St. Pauli, where he also operated the Indra strip club and a grind house cinema. Koschmider saw the moneymaking potential of teenagers and installed a jukebox at the Kaiserkeller stocked with rock-and-roll singles (Clayson 1997, 56–57; Miller 1960, 33–36). In spring 1960 he added live bands he met during scouting trips to Britain, as Germany did not yet have a crop of professional-caliber homegrown acts that could sing in English, which fans demanded as a marker of quality and fidelity to the original source of the genre (Fascher 2006, 85). Koschmider hired performers such as Tony Sheridan and the Beatles, who played their first of over 250 nights in Hamburg in August 1960 at the Indra before being moved down the street to the Kaiserkeller. These acts were instantly popular (figure 3).

Figure 3. Poster created by Erwin Ross advertising the Kaiserkeller, fall 1960. [View larger image.]

[2.6] Koschmider was instrumental in launching a trend, but to him the musicians and the music itself were disposable. It was the fans who created a scene, a community brought together by shared tastes, styles, and notions of authenticity (Cohen 1999). Who were these fans? At first, they were only those intrepid enough to venture down a dubious street known for kinky spectacles. The Kaiserkeller's location in a smoky basement—literally underground—also attracted those seeking refuge from the dominant culture's obsessions with cleanliness and respectability (McKinney 2004, 6–7; Siegfried 2006b, 145). Early audiences were the typical mix of seamen, tourists, and workers in the Reeperbahn economy, from "B-girls" and bouncers to strippers, that was found in other nightclubs. All sought release through dance, drink, and sex; as long as the entertainment was wild, they were satisfied. As word of the new bands got around, however, rock fans found their way to Grosse Freiheit 36, including Horst Fascher, a local boxer who soon became a fixture of the scene as a bouncer and manager.

[2.7] In 1960 the Kaiserkeller became a bastion of the Rockers, working-class devotees of early rock à la Elvis and Gene Vincent. They made the club the stage for their spectacular subculture: with their black leather and brash machismo, "they were the stars," as photographer Jürgen Vollmer put it (1983, n.p.). Vollmer moved in a competing youth subculture of bourgeois students and artists, the Francophile Exis (short for "Existentialists"), who were marked by their own distinctive dress (black turtlenecks, shaggy hair for men) and musical taste (chanson, cool jazz). A contingent of Hamburg Exis joined the Kaiserkeller audience in late 1960 after one of them, Klaus Voormann, chanced upon the club one night. His description of that moment is worth quoting at length:

[2.8] What was this? It came from the cellar club—music like I'd never heard. At home we listened only to classical music; boogie-woogie was obscene and the word "rock'n'roll" couldn't be thought, let alone uttered. Our clique listened only to jazz…But this was different. It went right through me and it pleased me so much I wanted to get closer. I was curious and damn scared. I crept carefully down the steps, closer to the magic sounds. I was used to the atmosphere in jazz clubs; the audiences there were "cultivated." Here, I realized that someone could grab me by the collar and punch me in the nose or snatch my wallet or chuck me out head over heels. I felt someone grab my hand—I pulled it back in horror to see the hand stamp now there. I stumbled further inside and was soon blinded by a ghastly ultraviolet light…Meanwhile, the band had changed. The sound was the same: earthy and fat, it landed in a region below the beltline. On stage, the blondest skeleton on earth tried to swing his long, bony leg over the back of the guitarist; he rocked and bobbed without dropping the mic stand. When a waiter barked, "take a seat or piss off!" I took the nearest stool, close to the stage. With huge eyes under my freshly washed mop of hair I sipped my beer and followed the scene around me. (Voorman 2002, 39–40; this and all translations are my own) (note 3)

[2.9] Voormann later cajoled his friends Vollmer and Astrid Kirchherr to visit the club with him, and they too became acolytes of the British bands banging out American rock and roll.

[2.10] Voormann's account reads like a conversion narrative, complete with powerful mystical forces ("it was like being struck by lightning") and a realization that his life had changed forever. What makes it significant historically is the border crossings it reveals. First, a geographic boundary is crossed: a banker's son out for a walk crosses into an area marked by sexual transgression and a threat of violence ("I wondered what my mother would have said if she had seen me in such a place"). Intertwined with this geographic boundary is one of class: rock and roll in 1960 was strongly coded as proletarian—lascivious, racially Other, beyond respectability. Once Voormann crossed that border and entered that cellar, he temporarily lost his class power: fear of attack glued him to his seat, meekly sipping his beer. But he soon gained new power through his connection with the music. Rock and roll opened him up to a new spontaneity suppressed by his bourgeois upbringing. He and his friends quickly became regulars, staked out space in the club, and befriended the bands—particularly the Beatles (note 4)—because, unlike the working-class Rockers, they could speak English. Their style in turn influenced the Beatles, who appreciated these "arty" fans and overcame their anti-German prejudices (Davies 1968, 83) (note 5). My sources don't reveal what the Rockers made of these bourgeois fans (Fascher, a working-class St. Paulianer, seemingly didn't care enough to have noticed them), though Vollmer writes that his circle eventually won their respect:

[2.11] Excessive vulgarity and violence was held in check by the cool act everybody put on. The Rockers and Exis shared this desire to appear disengaged…Of course, this somewhat precarious posture could not always hold up to the Rockers' heavy beer drinking…The Rockers wanted to be cool but they could not contain their violent energy. We didn't want to draw attention to ourselves but we could not deny our own sense of style. (Vollmer 1983, n.p.)

[2.12] In hindsight this encounter appears as a crucial moment in rock and roll's transformation from a niche working-class product into the cross-class, transnational lingua franca of youth in the 1960s. What bridged the class divide was not only a shared love of the music but youths' desire to distance themselves, through style, from the prevailing pieties of postwar West Germany, plus a shared sensibility that celebrated spontaneity, physicality, and youthfulness itself. It was no accident that this sensibility incubated in a place that encouraged liberation of the body.

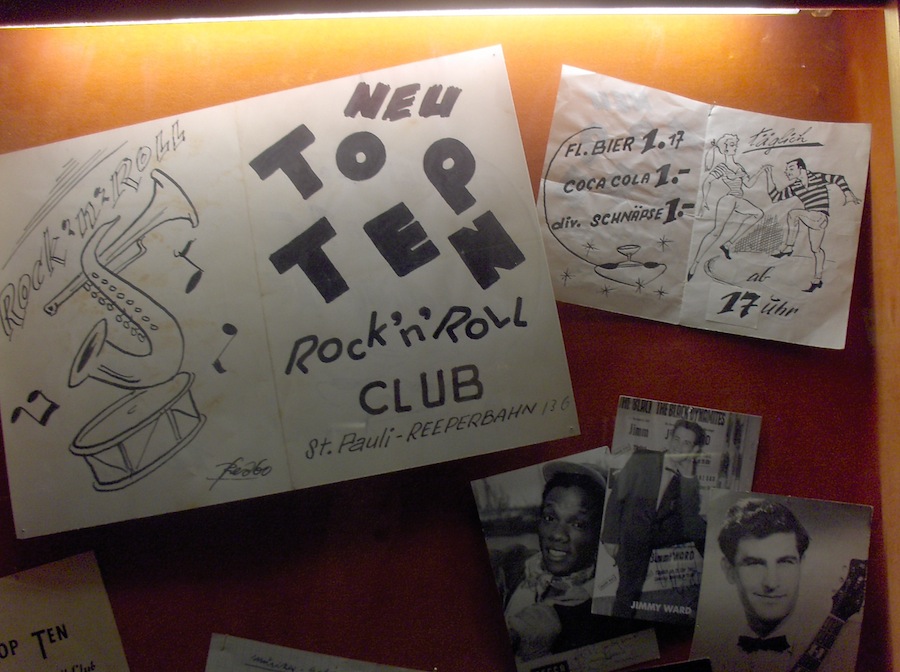

[2.13] Emblematic of youth's growing power as a social and a market force (as well as the passing of older, more class-based entertainment regimes) was the opening of the Top Ten in November 1960. Twenty-one-year-old Peter Eckhorn inherited his family's building at Reeperbahn 136, which for decades had housed a hippodrome particularly popular with sailors, who went there to quaff beer and ride draft animals (Günther 1962, 104; Thinius von Christians 1975, 115). But by 1960 the hippodrome was bankrupt, a casualty of the increasing mechanization of shipping (which meant fewer sailors in Hamburg) and the increasing dominance of sex-oriented amusements in St. Pauli. Eckhorn was persuaded by Horst Fascher that he could make money selling rock and roll, so Eckhorn had the spacious hall converted into a music venue. He poached Sheridan and the Beatles from Koschmider (precipitating the Kaiserkeller's demise in 1961); musicians even took up tools and paintbrushes to help renovate the space. The Top Ten quickly attracted new fans to Beat music, particularly white-collar workers and young women, who were less intimidated by a club on the brightly lit Reeperbahn. Other new clubs followed, such as the Hit Club, Club o.k., and, in April 1962, the Star Club, which would attract fans by the thousands and attain international renown (figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Original advertisements for the Top Ten, ca. 1961–62. Beatlemania Museum, Hamburg. [View larger image.]

Figure 5. "The misery is ending! The era of village music is over!" Flyers advertising the opening of the Star Club, April 1962. Beatlemania Museum, Hamburg. [View larger image.]

3. Music fans and social change in West Germany

[3.1] These early Beat fans don't appear to have left behind the kinds of artifacts created by other fan communities prominent in the cultural studies literature—any fanzines or bedroom shrines they may have created are lost to history. But they were nonetheless cultural producers in the sense of shaping and repurposing the commercial offerings available to them. Hamburg fans, whom musician Ulf Miehe called "the most expert" audience (1985, 97), demanded raw, uninhibited rock sung in English. At a time when the dominant culture was working overtime to cultivate respectability and repress the past, audiences ate up John Lennon's onstage Nazi jokes as if engaging in some cathartic ritual (Sutcliffe 2001, 99).

[3.2] These fans fashioned themselves as texts through the ways they moved and dressed, with teased-up hairdos or rocker jackets signifying their allegiances. Such activities eroded clear-cut distinctions between artist and audience while asserting "outsider-ness" in a society that prized conformism. They also asserted that cultural power was a democratic right available to all who wished to claim it (Fiske 1989, 147–48). I use the term democratic cautiously, but deliberately: cautiously, because it conjures up notions of formal organization or conscious opposition to prevailing economic and political structures, which do not apply here. The scene articulated no desire to stand the outside world on its head—rebellion was temporally and spatially contained. Gender stereotypes, for example, remained largely intact: while fans of both sexes revealed in interviews that they were sexually active, women were more monogamous and their sexual pleasure was an afterthought to their partners (according to Ruth Lallemand and Rosi Sheridan McGinnity, with whom I spoke in 2010). Homosexuals were tolerated but vulnerable to ridicule. Most of the first-generation Beat fans—and practically all of the female fans—would leave the scene and "settle down" into work and family life after the mid-1960s (even as they continued to follow their favorite bands whenever they could, up through the present day). Yet these fans' modes of consumption were a democratizing force in that they illustrated "a mode of radical democratization that put pursuit of pleasure at the heart of citizenship" (Chaney 2002, 145), especially if we accept a definition of citizenship that encompasses the right to speak or to gather in public spaces (as will be seen below in the protests over the Star Club's 1964 closure) (Canclini 2001, 15). This mode of consumption also advanced Germany's opening to the West, with English serving as both a sign of musical authenticity and a marker of identity among fans of all social classes who incorporated fragments of it into their daily speech (a gesture that made particular sense in Anglophilic Hamburg). English was also the language of the black American musicians fans revered: embracing it—and rock and roll in general—allowed these young Germans to distance themselves emotionally and politically from the "old Nazis" who had once banned swing and now demonized rock (Fascher 2006, 65). As young Germans' avid consumption of Americanized popular culture rode—and drove—the country's nascent shift toward a postmodern mass culture dominated by consumerism and mass media, it also promoted individualism and new, informal modes of behavior inimical to the spirit of authoritarianism still lingering in post-Nazi Germany (Maase 2001).

[3.3] Historian Detlef Siegfried presents Beat as a catalyst of West German liberalization and a precondition of the student movement of the late 1960s. Beat clubs served as "melting pots for unconventional styles and ideas" (Siegfried 2006a, 51), as we can see by looking at the composition of their audiences. For example, young artists and photographers working in media rubbed elbows at the clubs with denizens of St. Pauli's queer subcultures and sexual entertainment milieus, as well as "regular everyday people who liked rock and roll" (interview with Ted "Kingsize" Taylor, May 12, 2009). Siegfried sees the Star Club in particular as the "incarnation of the underground," a place where subcultural impulses crystallized and were then reproduced and popularized in the era's mass media (Siegfried 2006a, 51).

[3.4] But was Hamburg's Beat music scene an oppositional social force? It was, after all, commercially driven. Theodore Adorno dismissed Beat as a "machine-made product" of a "dirigistic mass culture"; even more sympathetic critics tend to view rock and roll after 1958 as less "authentic" because of its commercialization (Baacke 1968, 45–49). Most fans combined participation in the scene, a leisure activity, with the requirements of school or work, and many reject the notion that they were acting in any consciously political way. Voormann, for example, acknowledges that his clique's style was nonconformist but adds, "politically we were completely passive" (Voormann 2002, 34). An alternative view, however, is held by the sociologist Dieter Baacke, who in 1968 characterized Beat as "the silent opposition." Beat's potency lay not in any directly articulated political critique—Baacke distinguishes Beat fans from politically organized youth—but in the way it offered opportunities for leisure completely emancipated from the world of work. Beat adherents critiqued society by distancing themselves from it through shared signs and symbols (the "silent" aspect). Fans sought—and found—a sense of individual identity and recognition denied them at school and the workplace. Beat clubs simultaneously became places of group solidarity, a solidarity that led some to take on a more active political role. Michael "Bommi" Baumann wrote that Beat clubs (in his case in West Berlin) brought together youths who shared their frustrations and forged a consensus that "everything against the current order" and its "petit bourgeois mediocrity" was good (1998, 22–23). Baumann soon moved into radical leftist politics as a founder of the Second of June (1967) Movement and the Commune II (Kommune II). Günter Zint, a photographer, leftist activist, and son of a former Nazi party member, came from a "good bourgeois home" where authority was never questioned or political engagement encouraged. The Star Club, he says, was "the first place I experienced Widerspruch"—literally, "talking back." He states unequivocally that Beat music prepared the ground for the student movement and "1968" (Bye-Bye Star-Club 1987)

[3.5] Beat also acquired an oppositional character when adults castigated it as a sign of cultural decline. It certainly appeared socially disruptive to Hamburg authorities, who closely monitored the "Beat shacks" starting in 1961. Youth Protection Squads—a joint effort of police and welfare authorities—conducted undercover visits, searching for underage patrons and curfew violators. Their reports reveal that concomitant with their mandate to protect youth was a view of it as a social threat, a view that gained currency during rock and roll's early phase. The squads monitored issues such as underage drinking and "obscene" records in jukeboxes, but their most recurring concern was teenage sexual activity. They wrote up the Hit Club, for example, for having a condom dispenser in the men's bathroom. Young women were thought to be in particular moral danger, as the clubs were depicted as havens for runaways and "wayward" girls who were either working in the local sex industry or heading down that road. This concern with sex appears as part of the greater issue of discipline and social control (note 6). Youths were coming to St. Pauli in growing numbers without adult supervision, lured by a culture of music and pleasure so powerful that some were running away from "good homes" in Hannover, Munich, and even Scandinavia to experience it.

[3.6] This conflict over the Beat clubs climaxed in June 1964 when city official Kurt Falck ordered the Star Club shuttered because of unpaid taxes, Youth Law violations, and, above all, violence. The violence long associated with rock and roll became linked here with the club's practice of having waiters (many of them, like Fascher, the floor manager, trained boxers) handle disorderly drunks with their fists. Standard procedure in St. Pauli, this way of keeping order elicited grave concern among authorities and the local press when used in a youth-oriented club. While musicians and fans alike attest that this violence was not directed at them, Falck, with support from Hamburg's interior minister (and future chancellor) Helmut Schmidt, deemed the Star Club a "youth-endangering place" and declared war on its "vigilante methods" as part of a broad campaign to "clean up" St. Pauli in the interest of preserving tourism. Persecution had the curious effect of transforming club owner Manfred Weissleder, a tough character who originally opened the venue as a tax write-off subsidized by his more lucrative strip clubs, from calculating businessman into dogged advocate for the young people who made up the "Star Club nation." He fought tenaciously to refute his critics and expand the range of Beat concerts offered to the public. Fans reciprocated, with hundreds protesting the closure with peaceful sit-down strikes in the Grosse Freiheit. Asserting their right to cultural space, one group of female demonstrators brandished pacifiers to illustrate their contention that they were being treated like children with no right to speak. It's unclear whether these protests convinced the city to reconsider—more likely, the negative economic impact of the club's closure at the height of Beat's popularity compelled authorities to work out a deal. By late June Weissleder had transferred the club's license to one of his managers and the club had been allowed to reopen (Weissleder was also officially banned from the premises, but nonetheless retained effective control over operations). Still, the fight over the Beat scene's right to exist was far from over (note 7).

4. The Star-Club News: A voice for fans

[4.1] The same year that Falck tried unsuccessfully to close the Star Club, Weissleder began publishing the first German magazine devoted to rock music, the Star-Club News. This was Germany's first pop music publication to bear the direct imprint of fans. Indeed, the News offered new languages with which to conceptualize the identity of the generation born in the 1940s. The magazine also took a leading role in constructing youth as a consumer market while simultaneously critiquing the commercialization of youth culture in mainstream media. Through articles on music and other topics, as well as its very style, it questioned prevailing notions of respectability, identity, authority, authenticity, and even citizenship, and the everyday meanings of democracy.

[4.2] The initial rationale behind the founding of the Star-Club News was rather utilitarian. Weissleder hoped to use Beatlemania to promote his club, where the Beatles had played some 73 nights in 1962 (by 1964 he was advertising it as "the cradle of the Beatles"). He launched "Star-Club" as a brand with its own record label, radio presence, licensed clubs in other cities, booking agency, clothing, and other merchandise (something common today, but unheard of back then); the Star-Club News was the publicity wing of this empire (Siegfried 2006b, 213–16). What began in August 1964 as a 4-page newsletter grew into a 36-page monthly with glossy color front and back covers, affordably priced at 50 pfennigs. Circulation expanded to nearly 100,000 in 1965, reaching readers in Scandinavia and East Germany. While the News clearly served Weissleder's business interests, with features on bands he managed and albums on the Star-Club label, Weissleder also used his bully pulpit to critique "the establishment" more broadly and defend the Beat music scene against its critics. This critique was partly business driven: Weissleder often used the magazine to rail against Hamburg authorities who harassed the Star Club. But economic interests alone cannot account for his emotional solidarity with Beat fans and musicians. In the News's first issue, Weissleder, who was 36 at the time, spelled out his view of what was at stake in the clash over youth culture:

[4.3] To every sober thinking person, a Beatle haircut is better than the military crew cut of our recent history. And electric guitars make a more pleasant sound than the drums of the foot soldier or the newly revived fanfares of youth brigades ready to once again march eastward. When these forces claim to be sounding the call for freedom—a freedom in which your haircut or taste in music will be dictated to you—they are lying. Still! (Weissleder 1964)

[4.4] This statement squarely allied Weissleder with young Beat fans and against the unreconstructed prejudices of an older generation. Weissleder himself had chafed as a teenager under the Nazi yoke and despised the Third Reich for robbing him of his youth (he nearly threw a drunken John Lennon on the next flight back to Liverpool in 1962 for calling him a "Nazi swine," an insult Lennon hurled about freely in Hamburg [Rehwagen and Schmidt 1992, 140]). Weissleder and the News were not antiadult per se but opposed the hypocrisy and ignorance of those who preached authoritarian and militaristic values. Such antimilitarism wasn't entirely new in pop publications—historian Kaspar Maase has documented the subtle antimilitarism of Bravo, which is embedded in West Germans' distancing of themselves, by the late 1950s, from conceptions of a militarized masculinity that had been dominant in the first half of the century (Maase 1992, 155; Moeller 1998, 106). Weissleder's remarks seem to be a logical outgrowth of that development, stated plainly and boldly in a magazine that did not hesitate to ally itself with a new sensibility among German youth.

[4.5] When the Star-Club News was launched, West Germany lacked intelligent publications about pop music. On the one hand there was twen, a stylish monthly aimed at 20-somethings, known for its art photography and progressive tone on issues such as sex, race, and the Nazi past (Koetzle 1997). Its music coverage was driven by editor Joachim Berendt, an influential advocate for what he deemed "authentic" music, from Miles Davis to Delta blues (Hurley 2009). Berendt's tastes, coupled with twen's bias toward a more upscale and slightly older readership, meant an aversion to rock and roll, which it portrayed as an "inauthentic" commercial genre associated with a pimply proletarianism. For example, twen's first piece on the Beatles, in May 1964, offered a bemused look at their "hysterical" fans, while their music was assumed to be disposable; one reader subsequently griped that he didn't need twen to inform him that the Beatles were "coarse and loud" (note 8). Twen did not belong to rock and Beat fans.

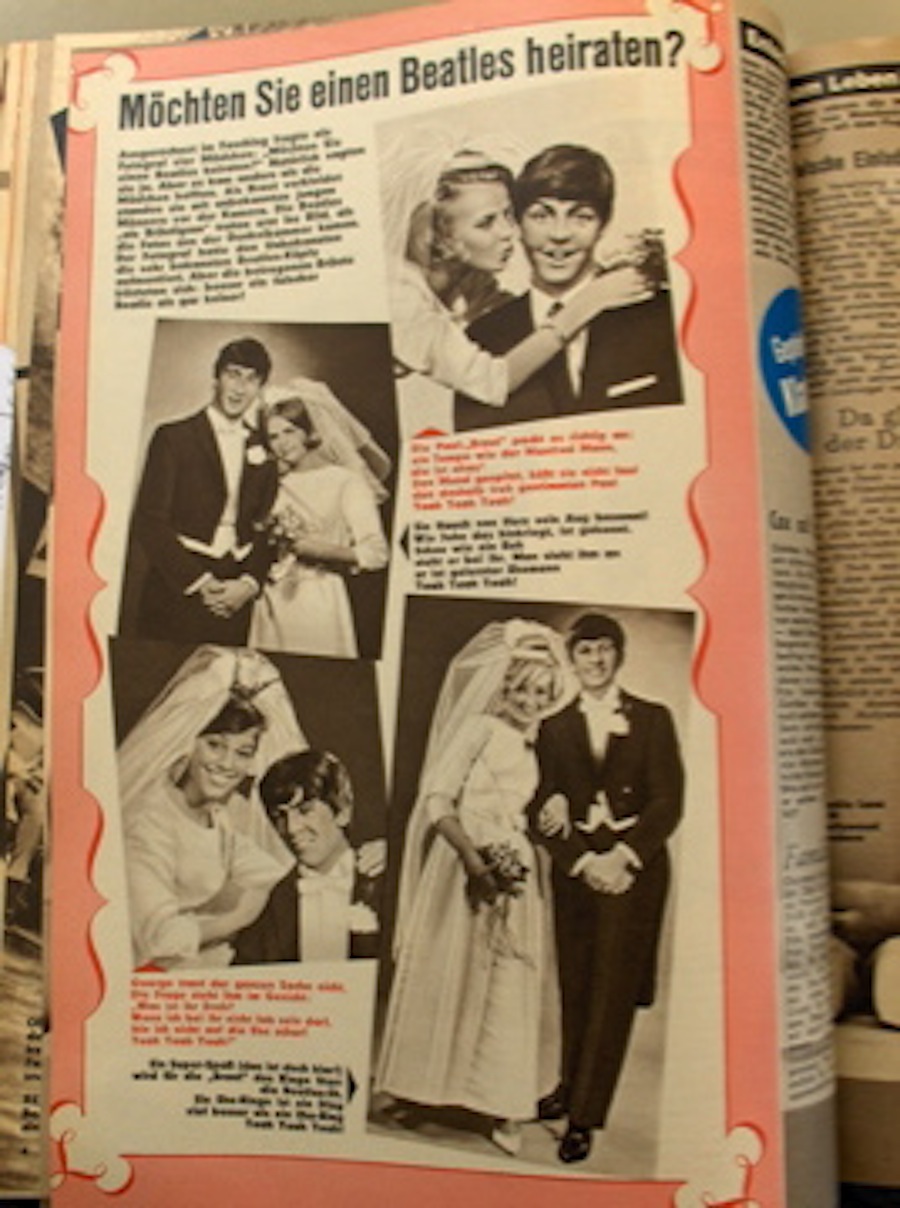

[4.6] The other side of the coin was Bravo, which billed itself as a weekly magazine of film, TV, and hit records and had over one million readers (Maase 1992, 104–9). Launched in 1956, Bravo injected American style, values, and body images into West Germany's "miracle years." Popular with not just teens but also housewives, Bravo emphasized pop idolatry, Technicolor modernity, and the supremacy of the Top Ten. Because its music coverage was chart driven, Bravo embraced Beatlemania in 1964, but it was ill-equipped to grasp the larger cultural ramifications of the pop explosion the band represented (note 9). Bravo squeezed the Beatles and other bands, like the Rolling Stones, into a prefabricated template of star worship, with articles on their favorite foods and their girlfriends, and even a Beatle wig contest. While Bravo did not employ the demeaning language of the tabloids or the boulevard press, which at times deployed terms reminiscent of Nazi-era rants against "degenerate music," Bravo covered Beat in articles written by reporters who seemed old enough to be Ringo's dad, and who used a breathless, silly style designed to appeal to the broadest possible audience (figure 6, note 10).

Figure 6. "Would you like to marry a Beatles [sic]?" Bravo, no. 9, 1965. [View larger image.]

[4.7] The Star-Club News broke with this kind of reportage, drawing on the enthusiasm of Beat fans to create a publication for discerning consumers of pop music. Its subtitle, "Information Report for Young People," reveals an intention to report seriously on what was still widely considered a trivial subject. Weissleder and his staff commented in every issue on the insipidness and dishonesty of German music journalism (no pieces were signed, but my sources agree that Weissleder wrote nearly everything [note 11]). As one piece put it, "The reader has a right to be correctly informed and, even in the domain of the lesser muses, not to be taken for an idiot" (note 12).

[4.8] The Star-Club News celebrated a new democratic culture of youths making music. Fans appeared not just as passive consumers but as active shapers of a music scene, and "fan" became a new identity. For example, fans were celebrated as "making" the stars, such as Hamburg's Rattles, winners of the Star-Club's first band battle in 1963 and the first German Beat band with fan clubs in Britain and the United States. The News treated fans as confidants and collaborators in an alternative journalistic enterprise. It solicited suggestions and critique while encouraging amateur journalists and young photographers (such as Günter Zint). Readers, whose letters appeared in great numbers in each issue, appear as coconspirators in a project to create something more than a mere teenybopper rag. As Weissleder wrote, "Our young readers are not unworldly, pampered hothouse flowers. They're intelligent, modern, realistic. We reject the stupid, illiterate style that the mainstream press thinks one has to use to address young people" (note 13).

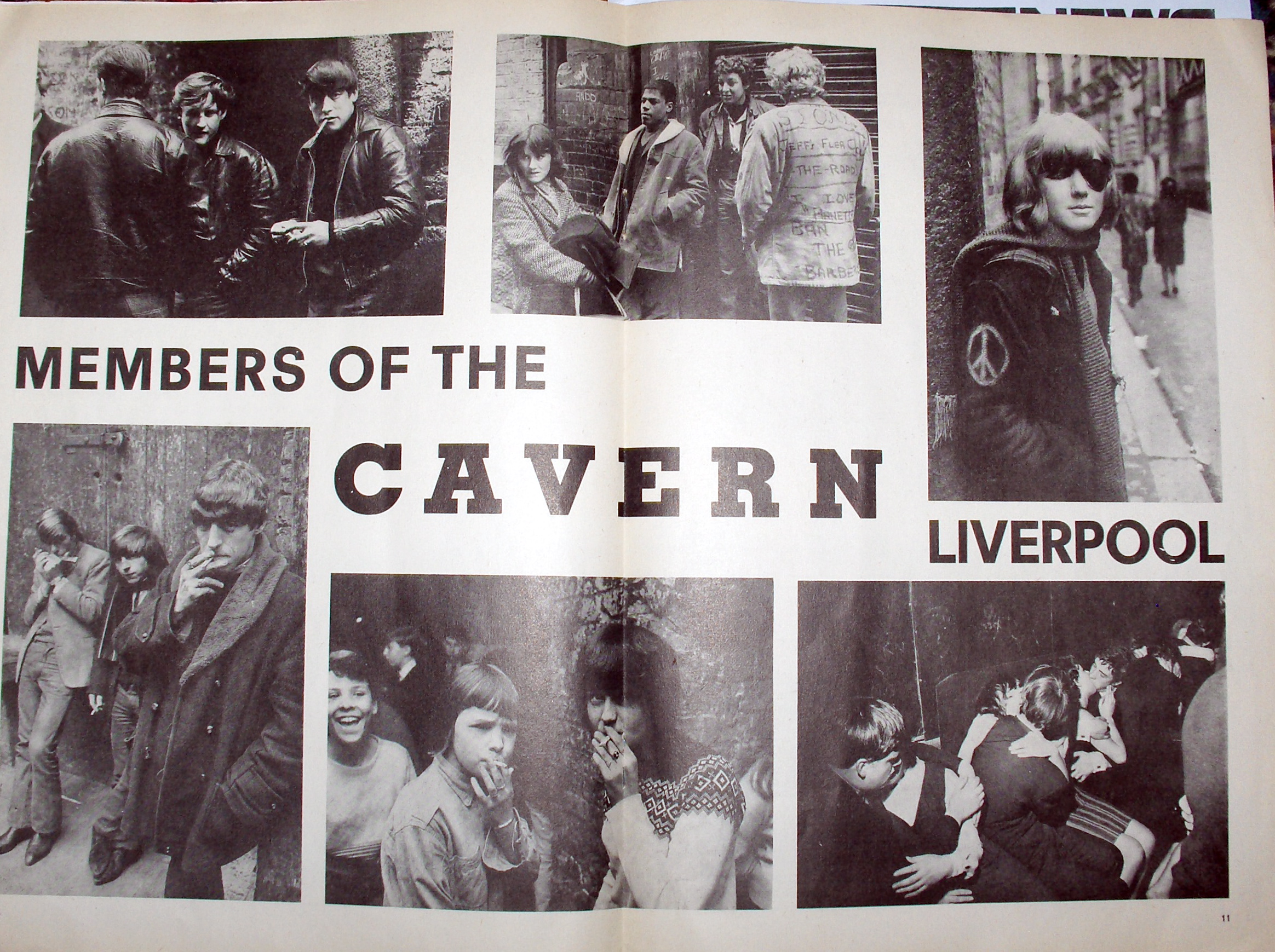

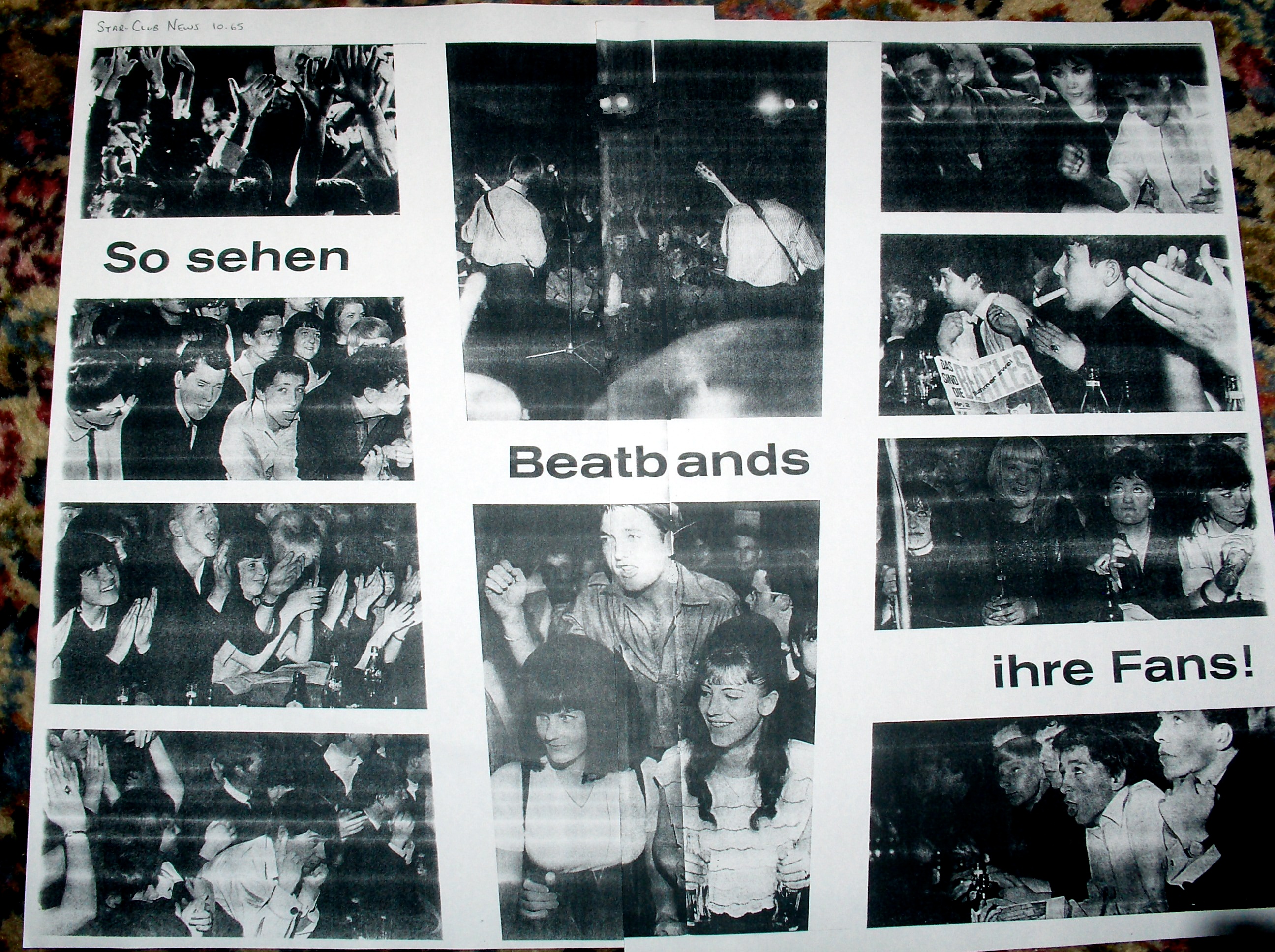

[4.9] The News also spotlighted fans as creators of their own spectacular subculture. A May 1965 photo spread on fans at Liverpool's Cavern Club shows teens displaying their identity through defiant poses and slogans scrawled on anoraks proclaiming "Peace" and "Ban the Barbers!" (figure 7). (In contrast, a 1964 feature on the Cavern in the Marxist student magazine konkret caricatured those same fans as the duped objects of media manipulation.) A photo essay on Star Club audiences shows "how Beat bands see their fans," signifying the interconnections between the two (figure 8). This symbiosis also emerges in articles conveying practical information on being in a band and in advertisements, many of which were for instruments, stage wear, and other utilitarian items for working musicians (or those who just wanted to dress like one). The centrality of the fan-musician symbiosis found full expression in the cover of the News's last issue, the "autograph hound" photograph of John Lennon and Gene Vincent. Within the Star Club community, the fan was a respected, indeed vital, member (note 14).

Figure 7. Beat fans at Liverpool's Cavern Club. Star-Club News, May 1965. [View larger image.]

Figure 8. "How Beat bands see their fans." Star-Club News, October 1965. [View larger image.]

[4.10] The magazine also became a forum for debate over changing notions of identity, such as the question of formal address. The July 1965 issue introduced a new editorial column by Ulla, the 17-year-old staff typist. In contrast to the boss's use of formal address (Sie) to readers, Ulla's "Halli-hallo" barges right into the intimacy of Du (you), her observations peppered with teen slang. Her next column reveals that her piece had set off a lively debate in the office over her use of Du. The "old man" objected to this "overly familiar swine-herder manner," which was common in other youth magazines, reflecting Weissleder's intention to elevate the discourse around Beat and his insistence that the News's readers, may of whom were over 18, be addressed as adults. Letters to the magazine continued the debate: one called Ulla's informality a stain on the News's otherwise "noble" style, but another asked, "Why we can't drop the stiffness of 'Sie'?" Weissleder ultimately both defended Ulla and declared that anyone who wished could call him Du—one indication of shifting attitudes toward this issue and a harbinger of the near future, in which young people would insist on informal address as a signifier of egalitarianism (note 15).

[4.11] Ultimately, according to the News, respectability resided less in forms of address than in intelligence and achievement. In its role as an advocate for fans and bands, the News often criticized inept authorities and established institutions. One piece dubbed the West German music industry a greedy horde that would rather put out novelty records than promote "real talent." Grubby promoters, many of whom were just yesterday "vegetable handlers and coal-Fritzes," reaped a "golden rain" of riches, of which the bands saw little (Weissleder, in contrast, was universally characterized by musicians as a demanding but generous employer). The music press was complicit in this swindle, and the News ran a series exposing the corrupt system through which industry publications rigged the music charts. The News called for a "record parliament" that would accurately reflect the tastes of record buyers—a bid for legitimacy for both the News and for fans, whose interests were not being served by an out-of-touch music press. The music press was also skewered for its retrograde notions of gender in a piece on the all-female Liverbirds. It showed the band laughing at an issue of Musikparade that assured readers that they were in fact female: "skeptics have asked whether the Liverbirds were real girls because they just couldn't believe the weaker sex was capable of hammering out such a great beat" (note 16). In this and other ways, the News set itself up as a hipper, more democratic publication for a knowing audience.

[4.12] "Knowingness" (Bailey 1994) also marked the News's take on the mainstream press as a whole, which it pilloried for its sensationalism and "glaring lack of expertise" in its rush to "get a lick from the honey pot" of the Beat craze (note 17). The Springer Press—publisher of the mass-circulation right-wing tabloid Bild—earned sustained reproach for its daily menu of horror stories and negative portrayals of youth. The News's gallery of rogues also included Kurt Falck, a stand-in for all those "guardians of youth" who in fact demonized youth:

[4.13] Bureaucrat Falck, celebrated court expert on skewering club proprietors and newly minted knight of an order of fools, was not the cause this time, as Lüneburg's Star-Palast was closed for violations of the Youth Protection Law. But no doubt officials there took their cues from their good old neighbor Hamburg, where dashing prosecutors have long taken aim, under any pretext, at the hated "Twist shacks" ("Twist," by the way, is just as much a misnomer as "shacks"). ("Palast-Revolution," Star-Club News, April 1965)

[4.14] This short article conveys several things. It establishes the magazine's knowingness by mocking the ignorant nomenclature of a hostile press ("Twist shacks"). It aims to evoke sympathy for Weissleder, who appears as the victim of idiotic moral crusaders. Finally, it sets up Weissleder as an ally who fights for youths' right to cultural space (note 18).

[4.15] This antiauthority posture was consistent, appearing in articles describing Beat fans being maligned and even brutalized by unsympathetic adults. When one young reader letter asked why there were no Beat concerts for fans under 16, Weissleder replied that officials "who falsely view Beat music as a manifestation of criminality" put up endless roadblocks. Youth style was another battleground. One piece explained singer Tony Sheridan's new front-combed hairstyle as an attempt to cover up a gash inflicted by a small-town German restaurateur who didn't like the fact that Sheridan's date was wearing trousers. Throughout 1965 the News defended young men who wore long hair, as in a piece blasting Hamburg's Eppendorf Clinic for refusing treatment to a shaggy 24-year-old, and a tongue-in-cheek feature juxtaposing pictures of the "great composers" in all their long-haired glory with ones of Beat musicians ("Beatles cuts have been around forever!"). A piece entitled "Mopp-Kopp" recounted real-life situations where Beat musicians and fans came to the rescue (such as carrying Chancellor Adenauer's luggage at a train station or pulling a wounded driver from his wrecked motorcycle) while adults proved unwilling to help, and urged young people to help their neighbors: "all Red Cross centers are taking blood donations—even from mop-top wearers" (note 19).

[4.16] The News also questioned prevailing notions of respectability in ways that can be construed as political. When Ulla criticized Hamburg police for turning water cannons on fans at a September 1965 Rolling Stones concert, she anticipated a broad debate in the West German press over aggressive crowd-control efforts by police during the Beatles' 1966 tour (note 20). Such commentary constitutes part of a broader discourse about respectability in a society still suspicious of youth as a mass. In hindsight we can see that ideas about youths' rights in the public sphere, generated within the Beat scene, were entering the mainstream even before the student movement thrust them onto the world stage in 1968.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] The image with which I began this article appeared in the last issue of the Star-Club News, which folded after its December 1965 issue because of disputes with the publisher. By then the original community of fans of rock and Beat music had exploded its boundaries, no longer confined to smoky cellars in disreputable side streets. But the Hamburg scene's role in incubating the youth culture pop explosion embodied by the Beatles remained central. Born at the confluence of commercial and subcultural impulses, the scene offered a model of at least temporary emancipation from the repressive conformism of West Germany's "miracle years." It generated a cross-class, cross-national solidarity among fans in which the social meanings of authority, respectability, and democracy could be questioned and eventually reworked. Fans' active role in this scene was a crucial element in the larger transition away from a youth culture defined by adults and designed to protect youth from "smut" and "moral dangers" to a new culture, generated by youth for youth, that strove to be something more than just disposable entertainment.

6. Acknowledgments

[6.1] This work was supported by a grant from the City University of New York PSC-CUNY Research Award Program. Thanks also to everyone who gave valuable feedback, especially Belinda Davis, David Imhoof, Jeff Johnson, Pieter Judson, Jay Lockenour, and Paul Steege.

7. Notes

1. Adenauer, of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), was chancellor from 1949 to 1963. The mail-order erotica business also flourished in this period, indicating a more complex sexual history than the period's surface respectability would have us believe (Heineman 2006).

2. The Lido advertised itself as "the largest and most modern dance hall in Hamburg." An October 1958 report from a tax inspector notes that the Lido "makes a clean impression." Records on the building's history to 1961 in Staatsarchiv Hamburg (hereafter StaHH), 442-1/95.92-15/7.

3. This account was written some 40 years after the event, though various versions differing only in minor details have appeared, starting with Hunter Davies's The Beatles: The Authorized Biography (1968). Voormann is aware of this story's mythic quality and accords it a prominent place in his memoir.

4. Voormann designed the cover of their 1966 album, Revolver, and played bass with Lennon and George Harrison in the 1970s; Vollmer restyled the Beatles' hair into the famous "mop top"; Kirchherr took the first professional-quality photographs of the band and became the lover of Stu Sutcliffe, the Beatles' first bassist, who died in 1962.

5. Lennon and Sutcliffe were themselves art students. Pauline Sutcliffe writes that her brother initially couldn't talk to German girls because he "felt guilty" about the war, but his new German friends subsequently had a profound affect on him artistically and personally (Sutcliffe 2001, 78, 102).

6. Hit Club cited in StaHH, 354-5 II Jugendbehörde II/Abl. 16.1.1981, 356-10.05-1 Band 2, Bericht über die Streife Nr. 137 am 18.7.62; sample reports on runaways in same file, Bericht über die Streife Nr. 138 am 19.7.62, Bericht über die Streife Nr. 148 am 1.8.62.

7. Falck's war against the club heated up in 1963 when Weissleder challenged a city ban on "youth twist concerts" as well as facing legal complaints filed by patrons beaten up at the club. Examples of press coverage, which was largely hostile to Weissleder, include "Heute früh: Razzia im Star-Club," Hamburger Abendblatt, June 18, 1963; "100 Polizisten im Twist-Club," Bild, July 19, 1963; and "Auf der Bühne im Star-Club: Jazz und Prügel," Hamburger Morgenpost, September 30, 1963. On the 1964 closure, see "Verbot für den Star-Club-Boss," Morgenpost, June 15, 1964; "Twens und Fans betrauern die Star-Club-Schliessung," Hamburger-Echo, June 24, 1964; "Demonstranten vor dem Star-Club," Morgenpost, June 24, 1964.

8. "Die Beatles sind da," twen, May 1964; letter to the editor in June 1964 issue. In 1965 twen slowly warmed to the Beatles because of their collaborations with filmmaker Richard Lester.

9. This phrase comes from Greil Marcus: "A pop explosion is an irresistible cultural explosion that cuts across lines of class and race…and, most crucially, divides society itself by age. The surface of daily life…is affected with such force that deep and substantive changes in the way large numbers of people think and act take place…[P]op explosions can provide the enthusiasm, the optimism and the group identity that make mass political participation possible" (Marcus 1976, 175).

10. For examples, see "Deutsche Twister in England ganz gross" and "Die Beatles YEAH YEAH YEAH" (Bravo, no. 6, February 1964, and no. 16, April 1964). Matheja (2003) surveys newspaper coverage and finds terms such as "baboon" (Paviane) and "plague of bugs" (Käferplage); pages 242 and 258 show some of these balding, bespectacled reporters.

11. Interview with Ulf Krueger, December 2008. Dieter Radtke, Weissleder's archivist, stated that his boss refused to delegate and "did it all" at the Star-Club News, with staff helping primarily with research (Rehwagen and Schmidt 1992, 148).

12. "Konjunktur im Beat," Star-Club News, May 1965; see also "Jugendpresse!," Star-Club News, April 1965.

13. "Liebe Star-Club Freunde!," Star-Club News, June 1965. See also "Wer schreibt, der bleibt," Star-Club News, February 1965; "Jugendpresse!"; letters to the editor ("Nicht verzagen—Manfred fragen!"), Star-Club News, September 1965. Ads were also placed in the April and May 1965 issues asking for submissions from readers, and a column entitled "Leser-Report" ran briefly in August 1965. Had the Star-Club News not folded abruptly in December 1965, it's safe to assume that it would have incorporated more fan-generated content.

14. "Members of the Cavern Club, Liverpool," Star-Club News, May 1965; "So sehen Beatbands ihre Fans!," Star-Club News, October 1965; "Autogrammjäger," Star-Club News,December 1965. Also Jürgen Holtkamp, "In Liverpool gibt's 1000 Beatles," konkret, June 1964; by 1966–67 konkret had reversed its negative view of pop culture.

15. See "Intern," Star-Club News, August 1965; letters page, Star-Club News, September 1965. Interestingly, informal address was already being used in ads for the Star-Club record label ("Eure Musik ist da!"), in accordance with the established advertising tactic of appealing to consumers through easy familiarity.

16. On the Liverbirds see "Rolling News," Star-Club News, June 1965. See also "Liebe Star-Club Freunde!," Star-Club News, April 1964; "Chruschtschows Abschiedslied," Star-Club News, May 1965; "Ei, ei!!!," Star-Club News, June 1965; ironically, Weissleder relied on Musikparade, Bravo, and Bild to publicize his club through advertising. On bands and managers see "Kollaps…und Hoffnungen," Star-Club News, April 1965. On the charts see "Kampf der Hitparaden," Star-Club News, June 1965; "Schallplattenparlament," Star-Club News, July 1965.

17. "Konjunktur im Beat." Elsewhere, "Ente" (Star-Club News, May 1965) blasts mob-inciting reporters for repeating the myth that in 1962 the Beatles had urinated off the balcony of their rooms next to the Star Club onto a passing group of nuns. Ironically, that myth found its way into the "respectable" Beatles literature, such as Philip Norman's Shout! (1981, 164).

18. Indeed, in this period Weissleder began a fruitless battle with Hamburg officials to have certain concerts at the Star Club designated "cultural events," and thus subject to lower taxes. See StaHH file 95.92-15/9 Band 5 (January–September 1966); also Siegfried (2006b, 224–25).

19. See letters to the editor, Star-Club News, September 1965; "Holzhammer-Methoden," Star-Club News, May 1965. On long hair see "Mopp-Kopp," Star-Club News, June 1965; "Hilfe abgelehnt," Star-Club News, November 1965; "Pilzköpfe gab es schon immer," Star-Club News, December 1965.

20. "Intern," Star-Club News, October 1965; on the 1966 Beatles tour and the press's softening tone vis-à-vis the band and their fans see Matheja (2003, 176–81). On police tactics at Beat concerts in this period see Weinhauer (2003, 286–91).

8. Works cited:

Articus, Rüdiger. 1996. Die Beatles in Harburg. Hamburg: Christians.

Baacke, Dieter. 1968. Beat—die sprachlose Opposition. Munich: Juventa.

Bailey, Peter. 1994. "Conspiracies of Meaning: Music-Hall and the Knowingness of Popular Culture." Past and Present 144:138–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/past/144.1.138.

Baumann, Michael "Bommi." 1998. Wie alles anfing. Hamburg: Rotbuch.

Bye-Bye Star-Club. 1987. Directed by Axel Engstfeld. DVD. Bremen: Radio Bremen.

Canclini, Nestor Garcia. 2001. Consumers and Citizens: Globalization and Multicultural Conflicts. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Chaney, David. 2002. Cultural Change and Everyday Life. New York: Palgrave.

Clayson, Alan. 1997. Hamburg: The Cradle of British Rock. London: Sanctuary.

Cohen, Sara. 1999. "Scenes." In Key Terms in Popular Music and Culture, ed. Bruce Horner and Thomas Swiss, 239–49. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Davies, Hunter. 1968. The Beatles: The Authorized Biography. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fascher, Horst. 2006. Let the Good Times Roll! Der Star-Club Gründer erzählt. Frankfurt a.M.: Eichborn.

Fiske, John. 1989. Understanding Popular Culture. New York: Routledge.

Grotum, Thomas. 1994. Die Halbstarken: Zur Geschichte einer Jugendkultur der 50er Jahre. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Günther, Horst. 1962. Hamburg bei Nacht. Schmiden bei Stuttgart: Franz Decker Verlag.

Heineman, Elizabeth. 2006. "The Economic Miracle in the Bedroom: Big Business and Sexual Consumption in West Germany." Journal of Modern History 78:846–77. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/511204.

Herzog, Dagmar. 2005. Sex after Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Hurley, Andrew Wright. 2009. The Return of Jazz: Joachim-Ernst Berendt and West German Cultural Change. New York: Berghahn.

Koetzle, Michael. 1997. Twen: Revision einer Legende. Frankfurt a.M.: Fotographie-Forum.

Krüger, Ulf, and Ortwin Pelc. 2006. The Hamburg Sound: Beatles, Beat und Grosse Freiheit. Hamburg: Ellert und Richter.

Kursawe, Stefan. 2004. Vom Leitmedium zum Begleitmedium: Die Radioprogramme des Hessischen Rundfunks, 1960–1980. Köln: Böhlau.

Maase, Kaspar. 1992. BRAVO Amerika: Erkundungen zur Jugendkultur der Bundesrepublik in den fünfziger Jahren. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition.

Maase, Kaspar. 2001. "Establishing Cultural Democracy: Youth, Americanization, and the Irresistible Rise of Popular Culture." In The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949–1968, ed. Hanna Schissler, 428–50. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Marcus, Greil. 1976. "The Beatles." In The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock and Roll, ed. Jim Miller, 172–80. New York: Rolling Stone Press/Random House.

Matheja, Bernd. 2003. "Internationale Pilzvergiftung": Die Beatles im Spiegel der deutschen Presse, 1963–1967. Hambergen: Bear Family Records.

McKinney, Devin. 2004. Magic Circles: The Beatles in Dream and History. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press.

Miehe, Ulf. 1985. "Beat." In Fans, Gangs, Bands: Ein Lesebuch der Rockjahre, ed. Carl-Ludwig Reichert, 96–106. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Miller, Frank H. 1960. St. Pauli und die Reeperbahn: Ein Bummel durch die Nacht. Rüschlikon: Müller-Verlag.

Moeller, Robert. 1998. "The Remasculinization of West Germany in the 1950s: Introduction." Signs 24:101–106. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/495319.

Mutsaers, Lutgard. 1990. "Indorock: An Early Eurorock Style." Popular Music 9 (3): 307–20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261143000004116.

Nichols, Richard. 1983. Radio Luxembourg: Station of the Stars. London: Cornet.

Norman, Philip. 1981. Shout! The Beatles in Their Generation. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Poiger, Uta G. 2000. Jazz, Rock, and Rebels: Cold War Politics and American Culture in a Divided Germany. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

Rehwagen, Thomas, and Thorsten Schmidt. 1992. Mach schau! Die Beatles in Hamburg. Braunschweig: EinfallsReich.

Siegfried, Detlef. 2003. "Draht zum Westen: Populäre Jugendkultur in den Medien, 1963–1971." In Buch, Buchhandel und Rundfunk: 1968 und die Folgen, ed. Monika Estermann and Edgar Lersch, 83–109. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz.

Siegfried, Detlef. 2006a. "Protest am Markt: Gegenkultur und der Konsumgesellschaft um 1968." In Wo 1968 liegt: Reform und Revolte in der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik, ed. Detlef Siegfried and Christina von Hodenberg, 48–78. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Rupprecht.

Siegfried, Detlef. 2006b. Time Is on My Side: Konsum und Politik in der westdeutschen Jugendkultur der 60er Jahre. Göttingen: Wallstein.

Sneeringer, Julia. 2009. "'Assembly Line of Joys': Touring Hamburg's Red-Light District, 1950–1966." Central European History 42 (1): 65–96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S000893890900003X.

Sutcliffe, Pauline. 2001. The Beatles' Shadow: Stuart Sutcliffe and His Lonely Hearts Club. London: Sidgwick & Jackson.

Thinius von Christians, Carl. 1975. Damals in St. Pauli: Lust und Freude in der Vorstadt. Hamburg: Christians.

Vollmer, Jürgen. 1983. Rock'n'Roll Times. New York: Overlook Press.

Voormann, Klaus. 2002."Warum spielst Du 'Imagine' nicht auf dem weissen Klavier, John?" Erinnerungen an die Beatles und viele andere Freunde. Munich: Heyne.

Weinhauer, Klaus. 2003. Schutzpolizei in der Bundesrepublik: Zwischen Bürgerkrieg und Innerer Sicherheit: Die turbulenten sechziger Jahre. Paderborn: Schoeningh.

Weissleder, Manfred. 1964. "Die haben's gerade nötig!" Star-Club News, no. 1, August.