1. Introduction

[1.1] On February 22, 2021, television series Word of Honor (Cheng, Ma, and Li 2021) premiered on Youku, a major Chinese streaming platform. The series would soon become another media sensation in continuation with the highly popular and profitable genre of dangai (耽改) production: media content adapted from online literature featuring romance among men. Previous productions like Guardian (Zhou 2018) and The Untamed (Zheng and Chen 2019) had all been commercial successes and had popularized dangai culture among mainstream audiences. However, the premiere of Word of Honor was deliberately low-key due to the mounting regulatory restrictions on dangai productions. Even so, no discretion would prevent the series in the following weeks from eliciting billions of social media impressions, attracting dozens of brand sponsorships, and gaining streaming contracts from international platforms including Netflix (Liu 2021).

[1.2] Enthusiastic fandoms should be credited with the explosive success of Word of Honor. Given its limited scale of official publicity, the series relied largely on word of mouth among audiences for promotion. The series obtained a high score on Douban, a Chinese social media platform focusing on cultural productions, earning over 250,000 ratings in one month, and the two leading actors won multiple brand endorsement contracts as their fan base surged (Xiaoyu 2021). In particular, many people joined the fandom as CP (couple) fans, devoting their ardor to the homosocial/erotic relationship between the two male protagonists. The CP fandom, named Langlangding after the two protagonists' character profiles, became a top hit topic on the largest Chinese microblogging platform, Weibo. However, the frenzy over Word of Honor was put to an abrupt end only a few months later when Zhang Zhehan, one of the leading actors, was exposed as having once visited the Yasukuni Shrine, where Japanese war criminals invading China during World War II were commemorated. Professional associations boycotted Zhang, and state media denounced his lapse as inexcusable. Consequently, Youku took down the series, and fan activities for the series were censored on Weibo.

[1.3] The success of Word of Honor marked the maturation of the dangai market, with both the economic and the cultural values of fan participation in full swing. Its downfall, although triggered by a particular scandal, reflected a broader government crackdown on dangai productions. Dangai was specifically targeted because of its representation of nonheteronormative social relationships while the government was taking an increasingly stringent approach toward regulating fandoms and the entertainment industry in general. By the end of 2021, all dangai productions had effectively halted. Nevertheless, the dangai boom in the 2010s presents a unique case in which a confluence of political, cultural, and economic forces conditioned the emergence of a niche for queer media production. Fandom, in this case, played an infrastructural role in connecting subcultural and mainstream domains and rendering the boundaries around genres, audiences, and cultural politics permeable (Phillips and Milner 2021) and convergent (Duan 2020).

[1.4] In this article, we present an explorative study guided by two research questions (RQs). RQ1 asks how the media ecology of dangai productions is constituted and how different parts of the ecology are interconnected, and RQ2 asks how dangai fandom has disrupted the ecological boundaries of media production and the ideological boundaries of state-sanctioned heteronormativity. A media ecology encompasses all the individual, organizational, institutional, and infrastructural actors contributing to information circulation in a media system and positions media productions as a result of the interactions among these actors (Wang 2018). The first half of the article investigates the composition of dangai ecology (RQ1). We review the theoretical perspectives on media ecology and fandom-based media production to offer a conceptual and analytical foundation.

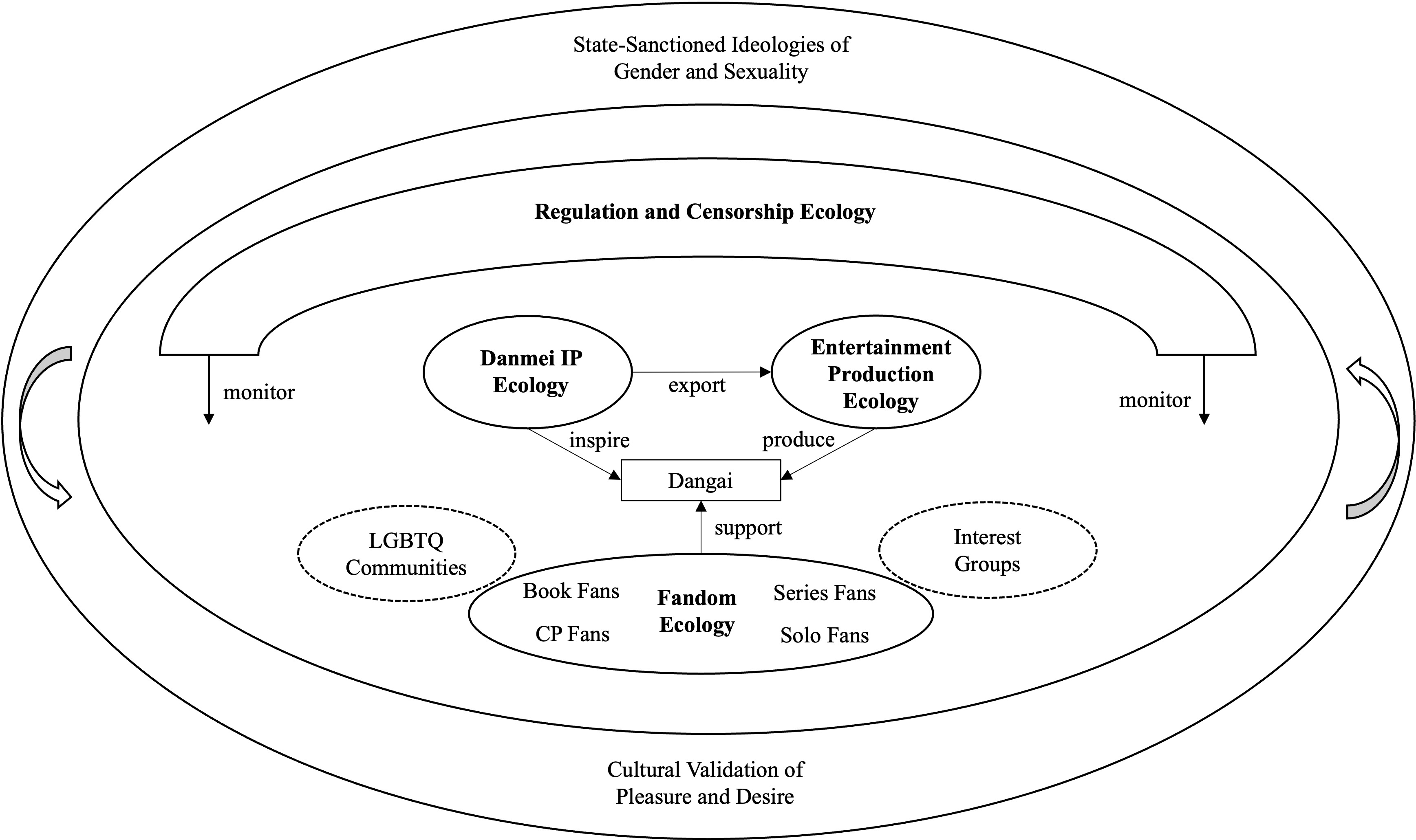

[1.5] We map out three specific ecologies—the danmei (耽美, romanticized gay love) intellectual property (IP) ecology, the entertainment production ecology, and the censorship and regulation ecology—to reveal where the structural conditions for a fourth ecology, dangai fandoms, emerge. We then zoom in on how fandoms are nested under the ecological structure of dangai production and complicate the ideological boundaries set for entertainment media. Informed by scholarship on fandom and queer representation, our discussion focuses on the disruptive potentiality of dangai. Although dangai fandoms do not subvert social norms, they do expose the dissonance between a heteronormative state that demands total unity of sexual ideology and a mundane public who only ask to indulge in their CPs. This dissonance is embedded in the ecological configuration of dangai productions and is articulated through fan activities that render the realms of platform economy, media production, fandom creation, and government regulation permeable and convergent.

[1.6] Building on Jenkins's (2012) theory of fandoms as a "third space" between subaltern resistance and institutional control, we propose a queer reading of dangai productions rooted in their ecological positionality to mobilize heterogeneous forms of cultural participation. This understanding of ecological queerness can be useful for scholars and industry practitioners to more holistically assess the impact of commercialized queer culture, particularly in restrictive media environments. Our objective is to identify dangai as an emergent media genre and advance further discussion of its capacity to represent queer sexuality.

2. Media ecology: Theory, method, and limitations

[2.1] We propose to conceptualize dangai production as situated within an ecology of producers, audiences, regulators, platforms, and capital sources. The social relationships among these actors amount to the flourishing or the demise of dangai fandom cultures. In a media ecology, social actors are interconnected through networks that morph beyond strictly horizontal or vertical structures (Anderson 2016), while the interaction among actors to mobilize networks in turn drives the reconfiguration of structural conditions for media production (Chadwick 2013). The emphasis on dynamics and interactivity here does not negate the constraints of social structures on cultural articulation but rather accentuates the transmission of power and influence across different domains of social life. Wang (2018) outlines how the ecology of media production could be mapped out through a typological analysis of the political economy underlying the sociocultural specificities of media texts. A broader ecology is compartmented into sectors so that functional differentiation and interactive mechanisms can be observed.

[2.2] This typology-based ecological analysis speaks to the conceptual understandings of media production as social practice (Couldry 2004), as transmedia storytelling (Scolari 2009), and as intertextual discourse (Fairclough 1995). It operationalizes these theories by making social relationships identifiable across different media texts, contexts, and platforms. As applied to this study, our analysis entailed the following steps. First, we identified the main actors participating in the broader ecology and preliminarily labeled their roles and functions in the ecology. Second, we grouped these actors under subecologies that had systematic distinctiveness. Third, we identified the social, political, cultural, and economic relationships among these actors within and among the subecologies. Finally, we explored the ideological implications.

[2.3] We delineate the Chinese dangai ecology based on several types of evidence. First, we have participated for a decade in various dainmei and dangai fandoms (e.g., reading and producing fan works, interacting with fans, and curating news and social media content on the fandom) on the media platforms Jinjiang, Weibo, WeChat, Lofter, and Archive of Our Own as well as in daily life. Second, the second author additionally has had industry experience of film and television production at a Chinese company from 2017 to 2020. Third, we also have examined relevant news reports, commentaries, and policy documents gathered through internet keyword searches. The information gained from industry experience mainly concerned the procedures of negotiation with copyright holders, content censorship, risk evaluation, and monetization of fan activities. The study did not yield any documented personal communication or identifiable personal information, and all consulted parties, including the two authors, were aware of what information would be included and gave consent.

[2.4] We sampled five productions that are representative of the dangai trend starting in the 2010s and conducted an ecological analysis of them. They all had a budget of over CNY 50 million (US$7.3 million), had broadcasting contracts with major streaming platforms, and continued to have active fandoms at the time of the study. They were selected as main examples to illustrate the ecological relationships and power dynamics around dangai productions. Two patterns—ecological convergence/permeability and queer fandom disruption—emerged from the analysis, speaking to our two research questions respectively.

[2.5] The methodological openness that ecological analysis necessitates, while useful for the holistic mapping of relationality, implies an epistemological limitation. The synthesis of theory and analysis means that media ecology would not fit neatly into the logical linearity of the positivist tradition of social sciences methodology. A situated analysis of ecological interconnectedness often brings in ambiguity, discrepancies, and inconclusiveness. Thus, we do not claim that the observed two patterns in this study are the only way to interpret dangai. In fact, it is precisely the contested meaningmaking that makes an ecological analysis felicitous. Given the nascence of scholarship on this emergent media genre, we deem it valuable to provide preliminary political-economic and sociocultural parameters and open the discussion about what ideological constructs may manifest through dangai.

3. Dangai fandoms in permeable ecology of convergent media

[3.1] The media ecology of dangai production formed and matured in the late 2010s. Table 1 presents the result of preliminary ecological analysis. The first row of the table identifies the four functional subsystems nested under the dangai ecology: danmei IP (the Chinese media industry refers to intellectual property as "IP"), entertainment production, regulation and censorship, and fandom. These four subsystems, while each having their own ecological configuration, together determine the content, reach, and cultural interpretation of a dangai production. The five productions listed in table 1 have wide circulation and serve as benchmarks of the success of dangai. Addicted (Ding 2016) was the first danmei adaptation to become a hit in the mainstream entertainment market. Although it was banned for its depiction of a homosexual relationship, Addicted set up the prototype for dangai productions to position themselves in the market and navigate censorship protocols. Immortality (Ho postponed), which was scheduled to premiere in 2022 but was blocked by regulators, may have been the last big-budget production—a ban on dangai was announced in late 2021.

| Ecological Position | Danmei IP Ecology | Entertainment Production Ecology | Regulation and Censorship Ecology | Fandom Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production Title | Original IP | Producer | Release | CP Fandom |

| Addicted [上瘾] | Are You Addicted? [你丫上癮了] (published on Liancheng, 2016) | Fengmang (budget: CNY 50 million) | IQiyi/Tencent, 2016 (taken down one month after release) | Heroin [海洛因]; Whale & Zhoumiao [鲸鱼与洲喵] |

| Guardian [镇魂] | Guardian [镇魂] (published on Jinjiang, 2013) | Shiyue/LeEco (budget: CNY 100 million) | Youku, 2018 (ratings: 3.2 billion views) | Weilan [巍澜] |

| The Untamed [陈情令] | Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation: Mo Dao Zu Shi [魔道祖师] (published on Jinjiang, 2016) | Tencent Penguin/NSMG (budget: CNY 200 million) | Tencent, 2019 (ratings: ten billion views) | Wangxian [忘羡]; Bojun Yixiao [博君一肖] |

| Word of Honor [山河令] | A Tale of the Wanderers [天涯客] (published on Jinjiang, 2011) | Ciwen/Youku (budget: CNY 50 million) | Youku, 2021 (ratings: 10.3 billion views) | Wenzhou [温周]; Langlangding [浪浪钉]; Junzhe [俊哲] |

| Immortality [皓衣行] | The Husky and His White Cat Shizun [二哈和他的白猫师尊] (published on Jinjiang, 2019) | Tencent Penguin/Otters Studio (budget: CNY 250 million) | Production completed; premiere blocked by regulator | Feiyunxi [飞云系] |

[3.2] The information in table 1 details the ecological parameters for the five productions that are discussed in later sections. Typically, a series producer buys the copyright of a danmei fiction from a fiction publishing platform for adaptation and contracts with a streaming platform for release. Sometimes, the streaming platform also invests in the production. Fans play an active role in this process. Of particular interest in our study are the CP fandoms, which support pairings of the leading male characters or actors. CP fans incentivize dangai producers to market homosocial/erotic representations, and their reinterpretation of the series ecologically constitutes the queer reading of dangai. The flow of content, capital, participation, and meaning among different ecologies as indicated in table 1 lays the foundation for our argument regarding RQ1: the role of fandoms in shaping the dangai ecology toward convergence and permeability.

[3.3] Fandoms are central and infrastructural in the dangai ecology. In participatory media production, fans enact multiple roles, directing the flow of content and developing canonical interpretations as the foundation for communal ties (Turk and Johnson 2012). This fan participation is not only embodied in creations like fan fiction, fan art, and fan vids but also serves as cultural leverage to legitimize the commercial value and political meaning of institutionally produced media. As in Jenkins's (2012) theory of the third space, fandoms are creative spaces where institutional and grassroots producers see their economic and cultural interests collide, align, or become compromised. The political significance of fan participation lies in the ability to bring different stakeholders into a cross-platform conversation on the meaning of media texts. According to Jenkins, the third space of fan creations is neither fully commercial nor fully discretionary. Fandoms can be ecologically positioned to cultivate both resistance and co-option, and their very nature of fluidity and openness complicates the direction of influence among stakeholders in media production.

[3.4] Building on the understanding of fandoms as participatory space and infrastructure, we further identify two properties that define the dangai ecology theoretically: permeability and convergence. A media ecology is permeable when information and content constantly traverse domains with different cultural norms and interpretative standards (Phillips and Milner 2021). The material boundaries around these heterogeneous domains can collapse, with information platforms becoming more connective, while the ideological boundaries persist and determine how media are purposed for meaning making. Permeability also describes an epistemology that decenters any interpretative authority and normalizes contestation. A permeable media ecology creates conditions for what Jenkins (2006) calls "convergence culture" to burgeon not as a complementary form of participatory consumption but as a mainstream model of media production for both individuals and corporations. Convergence takes place when actors in the ecology "make connections among dispersed media content" (Jenkins 2006, 3) and experience cultural productions as a practice that is networked and communal. Convergent media, when recreated, repackaged, and repurposed across permeable ecological boundaries, incorporate "heterogenous volitions" (Howard 2017) and "transmedia identities" (Jansson and Fast 2018) coming from varying discursive positionalities.

[3.5] As an extension to the ecological configuration in table 1, figure 1 visualizes how permeability and convergence characterize the dangai ecology. At the center are the danmei IP ecology and the entertainment production ecology as they coproduce the media text of dangai. A heterogeneous ecology of fandoms sustains the circulation of dangai and actively shapes its cultural interpretation. Besides encompassing multiple types of dangai fans, the periphery of the fandom ecology also connects to broader audiences among LGBTQ communities and cultural interest groups. Sitting atop all the other subsystem ecologies is the regulation and censorship ecology because it has the administrative power to monitor and intervene with publishing, series production, and fan activities. Although other ecologies can still influence government regulation via economic and civic means, in the Chinese context, stringent censorship demonstrates the paramount state authority.

Figure 1. Ecology of dangai media. Created by the authors (2022).

[3.6] As a synthesized answer to our question regarding the composition of dangai ecology, the evidence of figure 1 and table 1 in combination delineates the relationship among its major actors. The rest of our discussion provides a more detailed view of each element in figure 1. Particularly, the outer circle, depicting the dialectical contestation between state-sanctioned ideologies and mundane media consumption, builds toward the answer to RQ2 about how dangai fandoms disrupt the boundaries of ideological control and media production. Sections 6 and 7 present a focused discussion of dangai fandoms and their queer potentiality. In short, the censorship protocols embody the will of the state to uphold the heteronormative order while the participation of fandoms in the media ecology foregrounds the mundanity of pleasure and desire. These two forces clash in the dangai ecology, but dialectically, they also influence each other in constructing the ideologies around gender and sexuality.

4. Danmei IP ecology

[4.1] The ecological convergence and permeability of dangai production start from IP. A danmei IP is danmei media content, usually in the form of online literature or visual novel games, that has accumulated a fan base and is suitable for commercial adaptation. Jinjiang Literature City, an online literature website, is by far the most prolific platform hosting and exporting danmei IP. Four of the five dangai series listed in table 1 were adapted from fiction published on Jinjiang. Moxiang Tongxiu, a top Jinjiang author, had three novels adapted into animation series, comic series, television series, and radio dramas. Her 2016 novel Modao Zushi, later adapted as a television series under the name The Untamed, was bookmarked more than one million times on Jinjiang alone and sold for CNY 5 million (about US$780,000) as an IP.

[4.2] Founded in 2003, Jinjiang positioned itself as a "literature-centered feminine pan-entertainment platform" and aimed to "help niche readers find niche reads" ("About Jinjiang" 2021). The website developed a commercial model of charging membership fees for content, signing exclusive contracts with authors, and taking a cut of sold IPs. As this model matured, more authors wrote danmei fiction as a full-time or part-time profession, and the orientation toward community remained a key factor to maintain the site's user loyalty and activity. Readers could support authors by following their personal columns, upvoting their works, and writing comments and commentaries—all contributing to the commercial value of an IP.

[4.3] The danmei IP ecology not only supplies the content base for dangai but also sets up the cultural undertone for fandoms in the broader ecology. An IP is successful when it creatively integrates a variety of narrative protocols, including genres, tropes (or geng [梗]), and character profiles (or renshe [人设]). A genre sets up an IP's basic worldview and background. Tropes such as reincarnation (chengsheng [重生]), disclosure (diaoma [掉马]), or nemesis-to-lover direct the flow of plot. Moreover, the two protagonists forming a CP are profiled according to their personalities and attributes. For example, the author of Modao Zushi profiled the story's main CP as "noble and exquisite" (gaogui lengyan [高贵冷艳]) versus "rakish and intrepid" (xiemei kuangjuan [邪魅狂狷]), making this contrast a core dramatic tension. These narrative protocols contribute to convergence and permeability by serving as the basic unit of culture symbols for danmei IPs to be comprehended, packaged, and marketed across the dangai ecology. They constitute an interpretative framework coherent enough for media adaptations to manufacture a replication quickly, while open enough for diverse audiences to develop fandoms of different interests.

5. Entertainment production ecology

[5.1] When a danmei IP is ready for adaptation, producers take it over. An indicator of the mainstream visibility of dangai is the involvement of prominent production companies such as Tencent Penguin. The two dangai series it produces, The Untamed and Immortality, have a budget of over CNY 200 million (about US$31 million). Although they dominate the production process, the production companies have less control over distribution; they rely on specific streaming platforms to scope out target audiences. Compared with television channels, the streaming platforms target younger audiences, display a broader range of content, and face less censorship. All dangai series are broadcast on streaming platforms only. The largest streaming platforms, such as Youku, also participate in the production process, as was the case with Word of Honor. Beyond the production and platform companies, commercial investors also provide capital to the entertainment industry. The latter do not have much control over the production process, but they play an essential role in mitigating financial risk and coordinating resources. The commercialization of dangai thus provides a material foundation for ecological convergence and permeability.

[5.2] Dangai producers manage to expand their audience groups via established and innovative techniques of entertainment promotion. As dangai productions gain popularity, the producers start to cast actors with sizable fan bases. Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo, the lead actors in The Untamed, were idol singers with millions of fans. Their inexperience in acting may have lowered the quality of the series, but their fans' persistent views and recommendations helped to sustain a high volume of publicity for the series. Even after a production's release, it can generate further profits from publicity using its main cast. For example, the production team of Word of Honor staged a concert featuring the series' main cast; it sold out in fourteen seconds, with 600,000 people bidding for the 10,000 available tickets (Jie 2021).

[5.3] Meanwhile, dangai producers capitalize on fan activities as well to generate free publicity. When Guardian aired, the production team released a short promotional video on Lofter (Zhu 2018) calling for more fan creations. Similarly, Word of Honor released a promotional video on Lofter (Gong 2021) that featured lead actor Gong Jun thanking the fans for their creations. Given that dangai fan creations only circulate in relatively small circles, their creators view these promotional videos as an affirmation, and they reciprocate by committing more of their time and energy. Fan creations also effectively expand a production's audience after their creators share their works via social media platforms, yielding further ecological convergence and permeability.

[5.4] Once a production has accumulated a fan base, the streaming platform earns additional revenue by selling exclusive behind-the-scenes clips, soundtracks, and merchandise. Word of Honor released fifty behind-the-scenes clips, which were updated daily. These clips increased fan loyalty by providing a sense of insider connection. Dangai merchandise also sells well. The total revenue generated by all Word of Honor merchandise exceeded CNY 20 million (about US$3 million), and the main characters' costumes were auctioned for over CNY 850,000 (about US$133,000) (Yule Dujiaoshou 2021). CP fans, who ship the pairing of the two male main characters, show exceptional loyalty and willingness to purchase merchandise. After the release of Word of Honor, fashion company Tom Ford announced a joint endorsement from the two leading actors (the "Langlangding CP") for a lipstick, and within an hour of its launch the lipstick was sold out.

6. Regulation and censorship ecology

[6.1] In the Chinese media environment, government censorship and regulation have substantial enforcement power. As shown in figure 1, the influence of this sector of the ecology is wrapped around the other sectors. Two regulatory agencies monitor dangai productions: the National Radio and Television Administration (NRTA), which reviews the actual content of dangai productions and issues release permits, and the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), which oversees online activities, including danmei literature publishing and fan creations and discussions. Several professional associations, such as China Association of Performing Arts and China Netcasting Services Association, also assist the enforcement of regulations. This holistic approach to regulation means that dangai is subject to censorship, or entire bans, at every step of production and circulation. Starting from danmei IPs, the censorship of explicit depictions of homoerotic scenes is consistently stringent, so IP creators have to tactically circumvent censorship or give up sexual content entirely (Wang 2020). From the enforcement side, fan activities have stood out as a target. In June 2021, CAC launched a campaign to "rectify the disorderliness of fandoms" ("Cyberspace Administration" 2021). Technically, the campaign only targeted "malicious" fan activities, but the jurisdiction was vaguely defined. This surveillance held back investors' and sponsors' confidence in media productions that relied heavily on fandoms.

[6.2] While potentially inhibiting content circulation, the ubiquitous presence of censorship, along with the effort to evade it across the dangai ecology, added another layer of convergence and permeability. In fact, the censorship framework developed alongside the burgeoning popularity of dangai. In 2016, the censorship requirements for web series remained lax; however, after twelve episodes of Addicted aired on IQiyi and Tencent Video, the series was abruptly removed, leaving three episodes unreleased. Following the removal, an officer delivered a speech at the Chinese Television Industry Organization's annual meeting in which he stated that some web series intentionally depicted homosexuality and violated regulations (Li 2016).

[6.3] The prohibition of homosexual representation did not stop the production companies and streaming platforms from buying and adapting danmei IPs: dangai was created as an alternative to danmei, in response to censorship. Dangai substituted sex and romance between two men with an ambiguous relationship disguised as brotherly love. Because the adaptation did not explicitly depict homosexuality, it could proceed through the censorship process. After the release of Guardian, fans repurposed the term "socialist brotherhood" (shehuizhuyi xiongdiqing [ 社会主义兄弟情]) as a code for gay love. This term, with the sense of sarcastic humor behind it, caught on among dangai audiences as a way to communicate their endorsement of gay depictions (Ng and Li 2020). However, censorship protocols for web series tightened up quickly. For instance, both Immortality and Word of Honor passed the prebroadcasting content review in January 2021. However, according to new guidelines a web series had to pass an additional round of content review before it could be advertised on the homepage of a streaming platform. Word of Honor opted out of this step and aired without homepage advertisement in late February. Immortality, which failed to pass the extra round of review after a subsequent policy change, had to postpone its release indefinitely.

[6.4] This censorship mechanism channels the state-sanctioned ideologies around gender and sexuality that may not be congruent with dangai. In the guidelines issued by China Netcasting Services Association (2017), homosexuality is listed as "abnormal sexual relationships," which must be removed from media content. The document stipulates that cultural productions should conform to "correct political, value, and aesthetic orientations" and should not include "obscenity and vulgarity." In addition to its implicit references to homosexuality, another key element of dangai—androgynous representations of men—was confronted in an NRTA pronouncement that pledged to eliminate the "aberrant" trend of "girl-like men" (NRTA 2021). Here, the binary representation of masculinity as the antithesis of femininity is elevated to a moral standard by which to judge whether an actor is suitable for mainstream audiences. Two weeks after the pronouncement, NRTA explicitly asked the industry to boycott dangai (Bai 2021).

7. Gay love for a straight audience

[7.1] Queer disruption is mapped on the ecological configuration of dangai as fandoms offer alternative, and sometimes contested, readings of dangai. The mainstream popularity of dangai productions had its roots in the danmei subculture. Danmei originally referred to the Japanese literary aesthetic of pursuing the indulgence in pure beauty. It later became the label for romanticized male-to-male relationships among Chinese ACG (anime, comics, and games) and online literature circles (note 1). Cisgender women have been the primary force behind the production and consumption of danmei culture (Zhao 2019). This gendered nature of danmei fandom fundamentally affects how danmei is perceived as a niche "women's interest" media genre that deviates from the mainstream. According to Yang and Xu (2016), danmei fandoms blur the line between entertainment and politics by forming transient communities and transforming private matters of pleasure and desire into legitimate topics for public discourse.

[7.2] The expansion and convergence of fandoms in the dangai ecology further transforms the dynamics around gender and sexuality in danmei culture. Dangai literally means "modified danmei." Although homoerotism in danmei licenses the unconventional expression and exploration of sexuality for heterosexual women (Chao 2016), the representation of social relationships may still conform to heteronormative, patriarchal ideologies and reflect the conservative values held by many of the content creators (Zhao 2019; Zheng and Wu 2009). Nevertheless, Zhang (2016) argues that the female voyeuristic gaze on men in danmei, while motivated by gender inequality, contributes to a fluid identification with gender and the imagination of an emancipatory alternative to heterosexual privilege. This layer of gender dynamic means that the queer representation in danmei and dangai is generated from a heterosexual viewpoint, but the normative boundaries of heterosexuality itself are already disrupted by this viewpoint.

[7.3] The explorative reconstruction of gender and sexuality beyond the established binaries of masculinity/femininity and heterosexuality/homosexuality presents as a tie between danmei culture and LGBTQ communities (Xu and Yang 2014). The rise of dangai productions has further pushed danmei culture out of its circle and introduced many LGBTQ audiences—particularly gay men, who are initially not the target audience of danmei —to this female perspective on male intimacy. As a result, dangai fandoms embody queer attention (Zhao and Chu 2021) or queer visibility (Wang, Belair-Gagnon, and Holton 2020) in the Chinese media ecology, where explicit depictions of nonheteronormative relationships are rare. Building on this theoretical understanding, the next section completes our ecological analysis with a survey of the fandom ecology, with an additional exploration of how dangai presents an opportunity to disrupt hegemonic heteronormativity through fan participation within the constraints of commercialization and censorship.

8. Fandoms in dangai ecology

[8.1] Fandoms in the dangai ecology serve as the infrastructure for content circulation and the bridge connecting the danmei IP ecology and the entertainment production ecology. This infrastructure is disruptive in nature. As shown in figure 1, there is no one single dangai fandom, and the audiences for dangai identify with different circles or fandoms, sometimes multiple ones at the same time. The fact that not all the fandoms in the ecology match the profile of danmei subculture results in an interpretative diversity. Fans can take what interests them from a dangai production, amplify that particular element, and find community within particular fandoms.

[8.2] Fan activities are visible on fandom-specific platforms like Archive of Our Own and Lofter and on general-purpose social media platforms such as Weibo, Bilibili, Douban, and Tieba. On Weibo, the search entry #The Untamed# renders over 40 million mentions and over 40 billion impressions, and it consistently ranks among the top five most popular television series. On Lofter, the #WenZhou (#温周) entry for the character CP in Word of Honor generates 50,000 mentions, and the #LangLangDing (#浪浪钉) entry for the actor CP generates 120,000 mentions. Active fandoms around a dangai production coexist on these platforms, and it is common for fans to be present across multiple platforms. Thanks to the aggregation and recommendation functions of these platforms, intentional or incidental exposure to different fan communities creates both rapport and tension.

[8.3] One way to divide dangai fandoms is to differentiate the book fans from the web series fans. Series fans are introduced to the world of dangai directly through the lens of the web series whereas book fans have pledged their allegiance to the original danmei IPs and authors. To series fans, the quality of the script, acting, and setting in the series alone determines whether they want to binge on dangai. But book fans' primary concern is whether the series has managed to faithfully reproduce the characters and plots of the original IP. In the adaptation process, dangai productions want to attract as many new series fans as possible while losing as few book fans as possible because the latter are ready to consume the series immediately.

[8.4] Still, under the constraints of format differences, commercial considerations, and the need to pass content review, dangai adaptations are bound to diverge from their original IPs. Book fans often accuse producers of "damaging the original" (hui yuanzhu [毁原著]). The series Guardian, for example, was caught up in this controversy when it changed the novel's original background setting entirely. The universe of deities and specters was changed into extraterrestrial aliens, and many key plots in the original were butchered. The book fans' dissatisfaction peaked when the series changed the original happy ending to the death of both main characters. Fans lashed out on social media, urging the production's screenwriter to quit the profession (e.g., "Guardian screenwriter, please quit" [请镇魂编剧改行] 2018).

[8.5] Compared to series fans, book fans are also more committed to the danmei ideal of gay love. At the most superficial level is the compatibility of the actor's and the original character's temperament. This compatibility extends to acting and the overall posture of the actor, whose performance is judged for whether it "face-sticks" (tielian [贴脸]) the book's character. However, such expectations must be tempered because the highly idealized depictions of appearance and romance in danmei are hard to realize in a web series for both logistic and censorship-related reasons. Book fans are most intolerant about compromises on the homosocial/erotic themes of the original IPs. Before its release, The Untamed was rumored to have inflated the salience of female characters and added a heterosexual storyline among the main characters. Fans of Modao Zushi, the original fiction, were strongly opposed to this idea and commented fervently about it under the series' social media posts. Sometimes these kinds of "heterosexual adjustments" turn out to be strategies for attracting a broader audience and dodging regulatory attention (e.g., ZAKER News 2021). However, in hopes of introducing new series fans to the original danmei IPs, book fans have ended up mostly willing to support a dangai series despite its deviations from the original. The better a series performs among general audiences in the entertainment ecology, the more traffic is directed back to the danmei IP ecology.

[8.6] While book fans view their relationship with web series fans as symbiotic, CP fans, who ship the fictional or real-life pairings in dangai, and solo fans, who champion individual actors or characters, are more confrontational. These confrontations are visible in the circulation of their fan creations. Hardcore CP fans adhere to the principle of "no separation or reversal" (jin chaini [禁拆逆]), meaning that they will only accept fan creations that portray the CP as depicted in the danmei IP or dangai series. The gap between the CP fans and solo fans becomes particularly steep when it comes to RPS (real person slash) fandoms. Many of the web series fans only know the leading actors from their portrayal of dangai characters, as in the fictional CPs. This is an intentional marketing strategy for dangai producers and actors: blurring the line between fictional characters and real-life personalities creates a more immersive experience for fans. The tempering of homosexuality in dangai also leaves more room for the actors, none of whom openly identifies as gay, to boost their popularity through CP marketing. But an actor's solo fans often spurn this kind of publicity; they prioritize the actor's individual accomplishments over his dangai productions.

[8.7] Solo fans worry about the potential negative impact on an actor's career after he participates in dangai productions, which fall in the gray area of censorship. They also view the other actor in the CP as a rival. Prior to the broadcast of Word of Honor, lead actor Zhang Zhehan's studio posted a photo of him posing together with the other lead, Gong Jun. Zhang's solo fans were vehemently opposed to this kind of CP marketing, and they pressured the studio to retract the photo. The confrontation between the two leading actors' solo fans further escalated after Zhang's visit to the Yasukuni Shrine in Japan was exposed, followed by Zhang posting a handwritten letter accusing Gong of prodding young people into male CP fandoms (Wen 2022). Moreover, many solo fans do not relate to danmei culture and are repelled by the homoerotic connotations of dangai. In February 2020, solo fans of Xiao Zhan, one of the leads of The Untamed, led a high-profile campaign against the "Bojun Yixiao" CP fandom. Xiao's fans filed a complaint with the Chinese internet regulation authorities regarding the Archive of Our Own website, accusing fan creators on the platform of defamation for posting works that feminized Xiao. The complaint led to a temporary ban of the website in China, and many Bojun Yixiao fan creations were taken down from Lofter, Bilibili, and Tieba after coordinated reporting by solo fans (Gao 2020). The clash between solo fandoms and CP fandoms shows the coexistence of intolerance and acceptance of nonheteronormative media representations in the dangai ecology, which nevertheless disrupts the erasure of sexuality as a debatable agenda item in the Chinese media environment.

[8.8] The dangai ecology also encompasses peripheral groups of cultural interests who are loosely associated with the fandoms, as shown in figure 1. The proliferation of fan creations and the vibrance of fan communities facilitate the "overflow" (chuquan [出圈]) of dangai productions. For example, quite a few dangai productions feature elements of traditional Chinese culture, which becomes a point of connection between the circles of dangai and gufeng (古风, ancient ethos). Gufeng fans are interested in reviving traditional music, attire, verse, and other folk culture, and gufeng circles have expanded from online literature IPs to television series in parallel to dangai (Zhou 2021). With two professional singers in the main cast, The Untamed production team allocated resources to cultivating the music market as well. In collaboration with musicians and talent companies, the series made its name among gufeng fans for its high-quality soundtrack. This connection was further strengthened through fan creations. Fans of the series used newly composed gufeng music for fan vids, while gufeng composers publicized their works through these fan vids.

[8.9] Meanwhile, along with the mainstreaming of dangai, LGBTQ communities started to see dangai as a kind of queer cultural representation. The target audience of danmei or dangai was not gay men; however, during the brief window of lax regulatory policy dangai became the closest thing to queer representation in the Chinese media ecology and created a bridge between LGTBQ and straight audiences. LGBTQ people got to see the hesitant validation of nonheteronormative sexuality in mainstream culture, and straight dangai fans became temporary allies, at least for the sake of shipping their CPs. The threat to censor homosexuality in dangai incidentally connected the discrimination faced by LGBTQ people with the demand for more diverse content in the mainstream media market. Fandoms disrupted the ecological boundaries set for upholding state-sanctioned heteronormativity in media productions. In response to the derogatory depiction of dangai in Chinese state media, Chinese Rainbow Network, a leading LGBTQ organization, published a commentary article (Jiangyue Jushi 2021) to point out that the denouncement of dangai as cultural corruption was essentially homophobic discrimination and that banning internationally acclaimed dangai productions was an improvident policy.

9. Conclusion: Queer pathways in dangai fandom

[9.1] We have set out an ecological framework to understand dangai production and the multifaceted fandoms that amplify the cultural influence of dangai in answer to RQ1. We argue that the permeability and the convergence of dangai ecology both conglomerate heterogeneous volitions and build up the resilience, financially and culturally, for dangai to circulate among broader audiences. The mainstreaming of dangai, however, triggered resistance from the regulatory bodies that already have a firm control over all the sectors of the ecology. The capacity of dangai to foster consumption, discussion, and celebration of nonheteronormative media representation among different groups in civil society renders it a target. The uncertainty resulting from censorship quickly undermined the commercial value of dangai and hindered the influx of capital despite the strong market demand. The hype over dangai productions may have faded, but the network of fandoms remains an interface between niche and mainstream markets in the Chinese media ecology. These findings add to the scholarship on fandom ecology and demonstrate empirically how a third space of media production (Jenkins 2012) emerges through fan participation. This third space between corporate monetization and cultural resistance also serves as a buffer between the state and the civil society when mediating ideologies.

[9.2] In response to RQ2, we have found that the disruptive nature of dangai fandoms opens up a pathway for values and norms outside the state-enforced ideologies to gain visibility. This pathway is apolitical in the sense that it resides primarily in the realm of commercial entertainment media. But a form of queer politics emerges from fan participation, as fandoms base their consumption of dangai productions on individual expression of pleasure and desire. Here, the queerness of dangai does not solely hinge on equivocal depictions of gay love. As shown in our analysis, the relationship between dangai and state-sanctioned heteronormativity is dialectical, not dichotomous. It is not to the state's benefit to create an absolutely homophobic society while a large portion of dangai fandoms have limited interest in subverting structural inequality. Fans just want to ship their CPs, which represent their ideal of relationships. This idealization itself is queer because it renders the institutional regulation of gender and sexuality visible and forces top-down ideological apparatuses into the domain of mundanity. It is the very nature of heteronormativity to normalize one social group's authority to control other social groups, and gender and sexuality are media for this normalization. When dangai fans legitimate their interpretation of gender and sexual norms through participation in the media ecology, the singularity of cultural authority is disrupted. Censorship and regulation only deepen the disruption and further expose the tension between personal entertainment and ideological control. The queer politics of dangai, as we have theorized, add an ecological dimension to the discussion on queer visibility in media representation (e.g., Gross 2001) and see the functionality of queer representation beyond the binary thinking of assimilation versus subversion. We call for more scholarly attention to media genres like dangai, the content of which may still be largely contained by heteronormativity, and how their ecological positionality warrants a queer reading.