1. Introduction

[1.1] A scene in a popular Korean TV drama, Her Private Life (2019), depicts a girl dressed all in black standing on a ladder in an airport. She holds a professional camera, waiting for her idol. Other fans are also waiting. When the gate opens, the girl starts to take photos, and the crowd of fans rushes toward the idol, making the airport suddenly chaotic.

[1.2] The girl is a home master, or zhan jie. Zhan jie are fans who attend off-line events to take photographs, which they then post on social media. Fans wait on social media for the photos to appear and comment as soon as they are posted. K-pop has now become popular in China, and Korea's home master culture has arrived with it. As such, the scenario in Her Private Life could equally have taken place in either Korea or China.

[1.3] Fandom has been considered a participatory culture and highly relevant to the idol industry (Jenkins 2013). Fans gain emotional stimulation by consuming an idol's public image (Yin 2021) and making contributions to these idols, such as promoting them online or sending them gifts (Stanfill 2013; Yang 2009; Yin 2020). However, fan activities have changed the interaction with their idols (Lamerichs 2018): fans no longer simply enjoy idols' official output but also innovatively contribute to the public image of new idols (Sun 2020; Yin 2021).

[1.4] However, few studies have focused on zhan jie. In fact, what distinguishes zhan jie from other productive fan groups such as slash fans is their unique media process: while Chinese slash fans usually write on online platforms such as Lofter (Pang 2021; Zhang 2020), zhan jie's fan practices are always off-line to online, with zhan jie taking pictures off-line, then posting the best ones on social media to interact with peripheral fans (Sun 2020). During our literature review, we only located one existing study on zhan jie, focusing on fan labor. In contrast, we emphasize zhan jie's core position among fan groups to define interactions among zhan jie (as core fans), idols, and other peripheral fans. Specifically, we examine how Chinese zhan jie as productive fans impact the Chinese idol industry. In Chinese, zhan means "site" and jie means "older sister"; here, zhan specifically refers to fan sites, that is, fan-created websites where zhan jie upload their photos, and jie describes respectful women. From thirty-two months of participatory observation, we identify the interaction between zhan jie and their idols, with zhan jie acting as mediators between idols and fans, thus shaping a unique fandom culture in China.

2. The position of zhan jie in Chinese fandom

[2.1] Fan groups are not homogeneous but have different levels of participation (Botorić 2021). Fans within a single fan group can be divided into different hierarchies, which are mainly based on the fans' knowledge and reputation (Booth 2018; Lynch 2020). Vlada Botorić (2021) introduces the concepts of core fans and peripheral fans to fandom studies, arguing that peripheral fans, who produce less, rely on core fans, who are usually highly productive. The word "production" here refers to a general estimation of the contribution fans make to idols, including actions such as drawing pictures, making comments, and buying multiple albums. Correspondingly, core fans have a more extensive influence on fan groups, and their words seem more convincing when conflict occurs (Botorić 2021). Consequently, the power inequality within fan groups creates a huge gap between core and peripheral fans (Botorić 2021).

[2.2] This kind of hierarchy also exists in Chinese fan groups. The Chinese fan community is highly centralized and well trained (Wu 2021). Xueyin Wu (2021) describes a landscape that is under the control of a fan club (a fan organization that deals with all kinds of fan issues), which is split into different functional divisions, each taking charge of different tasks and having its own social media accounts. Following the fan club's instructions, peripheral fans participate in different activities, including data labor, promoting their idols' photos, and writing positive comments about them. Fan clubs also design elaborate discourses to retain fan loyalty for idols. They claim they are like their idols' mothers, with a duty to take care of them: without the mother-like support from fans, their idols can never become successful. In Wu's Chinese fandom landscape, fan clubs and their divisions are core fans, while peripheral fans listen to their commands to benefit their idols.

[2.3] However, zhan jie differ from core fans serving fan clubs: they do not have the ability to control but rather use their unique productivity to ensure their own special status. Zhan jie share photos with peripheral fans, attracting many as followers and enabling themselves to become "influencers" within the fan groups (Long 2022). In this sense, zhan jie are another kind of core fan, employing two abilities to acquire core fan status in the idol industry: first, they can easily make contact with their idols because they often attend off-line events, and second, idols are likely to take their ideas into consideration because they are influencers among fan groups (Long 2022).

[2.4] Called zhan jie in Chinese, a fan station owner is called homma, short for "home master," in Korean (Sun 2020) and is one who builds a cyber home for fans, meaning that fans in Korea refer to fan stations as homes. In Western countries, a fan's cyber home, like a fan station, is a forum where fans can communicate with each other (Kibby 2000). However, in East Asia, a fan station or cyber home is more specific than an online platform, consisting of a fan club whose members have specific functions such as data laboring or organizing events. These fan clubs have one or more accounts on different social media platforms to keep in touch with their fans. Our use of the term zhan jie therefore refers to a group of fans who take flattering pictures of their idols. In China, zhan jie use Weibo to share their pictures, often with the hope that their images will attract more fans (Zhang and Negus 2020). They photograph their idols off-line and post their pictures on specific (usually social media) platforms. In China, a fan station (fensizhan in Chinese) is always associated with various functional fan organizations (Wu 2021; Yang 2009), so we use the specific term zhan jie rather than the direct translation of fan station owner.

[2.5] Fans often dream of meeting their idols face to face. Due to money and time limitations, most can only follow their idols online; however, they can enjoy pictures of their idols in the home that home masters build for them. In China, whenever idols attend events, zhan jie also attend, taking pictures of their idols and posting them on their cyber home (usually Weibo). Zhan jie also go to hotel entrances and transport stations to take photos. After they post their pictures, fans leave likes, comment, and share the content. Zhan jie sometimes also sell merchandise related to their idols using photos they have taken since fans love to use idol-related products in their daily lives (Yin 2021). For instance, in August 2020, the cyber home of Chinese idol Cai Xukun, Bayuemengyouzhe, sold photobooks of him, earning more than RMB 1 million.

3. Method: An exploratory participatory observation

[3.1] Participant observation is "the process of entering a group of people with a shared identity to gain an understanding of their community…Through the experience of spending time with a group of people and closely observing their actions, speech patterns, and norms, researchers can gain an understanding of the group" (Allen 2017, 1188). We took a strict participant observation approach, with the first author being a reputable zhan jie herself who is engaged in activities related to the idol industry, both online and off-line. She maintained communication and collaborated with other zhan jie during this piece's research, writing, and revising.

[3.2] This participant observation approach followed an insider's perspective, allowing the first author to record and discuss her activities and the virtual or physical places she visited, which in turn formed an interactive verification of data collection with other interviewees (Jorgensen 2008). Participant observation has been widely used to study fan communities, as it allows for a firm focus on fans themselves, their relationships with each other and their loved ones, as well as fan self-interpretation (Waysdorf and Reijnders 2018; Yamato 2016). This approach also allows researchers to enter areas where research subjects congregate to gain "a sense of how these locations [feel], in a physical sense, and the affordances that they engend[er]" (Waysdorf 2020, ¶ 5.3).

[3.3] In May 2020, a zhan jie with two years' experience asked the first author to help build a new cyber home for a female idol from a talent show. The first author agreed and told her about the present research. The zhan jie also invited her into three WeChat groups with five hundred members (the maximum number of WeChat group members). The members in these WeChat groups are all Chinese zhan jie of female idols from talent shows. The groups share information and ask others to help them photograph their idols for pay when they cannot attend an off-line event in person. After trading photos with other zhan jie, the first author was invited to join additional WeChat groups, enabling her to communicate with more zhan jie. The first author is now a member of nineteen active zhan jie WeChat groups with two hundred to five hundred members each. Her initial cyber home has nearly twenty thousand followers and an average of one million readers per month, making her a successful Zhan Jie in Chinese fandom culture. This author also attended five different off-line events to take photographs and make contact with other zhan jie.

[3.4] When the first author entered the WeChat groups, she indicated her identity as a researcher on her home page. Although some zhan jie were afraid of being exposed to the public, most chose to keep contact with the author. Though they refused to be interviewed, they allowed the researcher to observe their home pages to investigate their activities with the guarantee that their personal information would not be revealed. The researchers also considered the power imbalances between the researchers and the interviewees. Notably, the first author is a consumer of zhan jie because she has purchased photographs from some of them. However, the zhan jie were informed that they were free to leave the study at any time, that their choice would not influence their fandom relationship, and that the first author would still purchase photographs from them. Three zhan jie chose to leave after being informed of the research, while eighteen gave written consent to be interviewed. Since some are familiar with each other, we believed more data could be collected if they could talk together. Therefore, we conducted one-hour in-depth interviews with twelve zhan jie, a three-hour focus group with four zhan jie, and a two-hour focus group with two zhan jie, according to their social networks. All interviews and focus groups were conducted online and in Chinese, the interviewees' native language. The first author provided translations of the transcripts.

[3.5] Zhan jie's activities usually fall within a gray area of the law, are highly criticized by the Chinese public, and might be banned by the Chinese government as part of the Qinglang movement (a policy announced by the Chinese Communist Party aimed at regulating toxic Chinese celebrity culture; Stevenson, Chien, and Li 2021); therefore, the participants requested anonymity. Although the zhan jie took part in our interviews, they mostly refused to allow their words to be used directly. Therefore, we only present parts of the interviews, with most of the remaining content devoted to analysis.

4. Characteristics of zhan jie

[4.1] Based on our analysis of zhan jie and fan society, we identified five characteristics of professional zhan jie. First is centralization (Hills 2002): thousands of Chinese zhan jie are distributed mainly across a few WeChat groups and Weibo Super Topics. Most are familiar with each other, and they often gather at off-line events, therefore creating a centralized community.

[4.2] Privacy is the second characteristic. Zhan jie are afraid of being exposed to the public (Dym and Fiesler 2018), so they have unwritten rules that members adhere to. For example, to protect their privacy, they cannot reveal the content of their communications with each other to the public.

[4.3] Third, because of the privacy requirements, zhan jie are in a closed online community, which exists on different platforms such as Weibo and WeChat. Newcomers need to be invited to participate in events and gain information (Yi 2013). Indeed, zhan jie's activities mainly take place in a gray area of the law: they seek their idols' personal information, reveal private details, and sometimes cause chaos in public spaces—all with the idols' acquiescence, as zhan jie believe. Consequently, they lose legal support in some circumstances, such as conflicts with ticket scalpers. Therefore, zhan jie groups believe that they should help each other: they share information and customers and offer assistance during conflicts.

[4.4] Moreover, since zhan jie operate within such a gray area, they must be invisible (Yi 2013). They perhaps should keep the groups closed and investigate every member they invite to protect their idols and themselves (Dym and Fiesler 2018). If it is too easy to enter the group, newcomers might not know the unwritten rules and thus might cause harm for their idols. Once a zhan jie invites a newcomer, they are responsible for teaching them the unwritten rules. Additionally, given that zhan jie's activities are protected by strong discretion, public ethics and morality do not incorporate zhan jie's activities. Therefore, another self-imposed rule is that they should keep secrets within their groups. For instance, chat logs cannot be posted in public, and methods they use to find information cannot be shared with outsiders.

[4.5] The fourth characteristic of zhan jie refers to the trades among these fans (Brodie et al. 2013). Unlike other productive fans, especially slash fans, zhan jie tend to be active on off-line sites, thereby accruing high costs: in addition to tickets, there are large expenses for transportation and accommodation. To cover part of these costs, zhan jie attempt to monetize their works by making peripheral goods with pictures they have taken and selling them to fans. To boost sales, many zhan jie keep their best pictures rather than posting them on social media, instead using them to make merchandise. "Once fans hear about the unpublished pictures, they are easily attracted and sales increase," said a zhan jie with five years of experience. Zhan jie always come up with various creative merchandise, such as luminous lights and tarot cards with idols' pictures. With the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, zhan jie made mask holders with idol pictures. The same zhan jie continued: "But we normally sell peripherals at least twice a year—once for PB [photobooks] and once for calendars. These are the most profitable and the best sellers. Fans like to buy them because they include our best-looking pictures, usually with unpublished pictures; and they are paper products, so the cost is low."

[4.6] Unlike South Korea, China is very large, and its major cities are widely dispersed, with Beijing and Shanghai more than one thousand kilometers apart. This means that Chinese zhan jie "can hardly attend most of their idols' activities in one city like Korean home masters, unless we quit our jobs," as one Chinese zhan jie with three years' experience explained. As a result, Chinese zhan jie sometimes ask other zhan jie to film their idols, most of the time for a fee. These zhan jie who shoot photographs on behalf of other zhan jie are called dai pai, or "photography agents."

[4.7] Zhan jie often find dai pai in one of three ways: through friends, zhan jie–oriented WeChat groups, and social media platforms. They communicate with each other on the time and price of the deal, then confirm that the dai pai's skills and devices meet their requirements by looking at sample pictures. After that, zhan jie must pay half of the price as a deposit to complete the reservation. Zhan jie and their dai pai maintain contact, especially at the shooting site. The dai pai must take photos while selecting and transferring parts of their images to the zhan jie so the zhan jie can first post the images to their social media accounts, attracting attention. After the event is finished, the dai pai uploads all photographs to Baidu Web Drive, a Chinese cloud service, and sends them to the zhan jie, who pays the remaining half of the price to complete the deal. As a result, a hidden dai pai–zhan jie–fans industry chain has emerged.

[4.8] Fifth, zhan jie have their own set of ethics, just like other professions. These ethics can be separated into those related to idols and those related to the zhan jie themselves, each intended to protect their respective groups. The foundation of the ethics related to idols is zhan jie's love for these idols. In essence, zhan jie want to use their pictures to show how beautiful their idols are, help the idols build a positive public image, and attract more fans to them (King-O'Riain 2020). Therefore, a basic rule is to never post a bad picture, even if a zhan jie has not successfully photographed any of their idols looking good.

5. Catch me if you can: A public-private dynamic equilibrium process

[5.1] In the idol industry, fans are curious to uncover their idols' secrets; however, they may fall in love with another idol when they realize they have nothing left to discover about the previous idol (Hills 2005). Consequently, idols usually attempt to maintain an air of mystery to maintain fan interest (Shin 2009). This process creates a dynamic equilibrium relating to capital, reputation, and fandom emotional flow.

[5.2] Through their production activities, zhan jie use this equilibrium to reframe how fans interact with their idols. Traditionally, fans can only be stimulated by images from official sources, and idols can control the messages circulated to their fans. However, fans can now also be informed by zhan jie, who help idols keep their fans, although they sometimes create too much exposure.

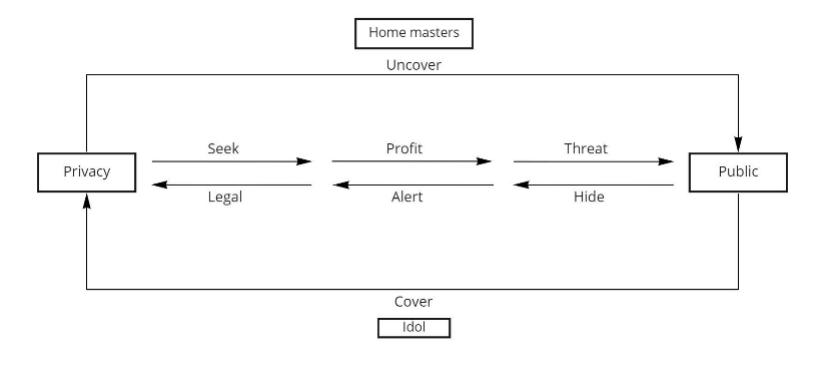

[5.3] In this way, zhan jie create a new game for peripheral fans and idols. They destroy the mystery surrounding their idols while also helping them consolidate and expand their fan base (Duits, Zwaan, and Reijnders 2018). Idols thus have complex emotions toward zhan jie—including appreciation and, sometimes, anger—and aim to retain them. However, they also try to limit zhan jie's invasions of their privacy to maintain their mysterious image; hence, the two parties play a game of "catch me if you can." Zhan jie want to photograph their idols in every public spot and post these pictures on social media, claiming that their activities help their idols consolidate their fan bases. Idols, on the other hand, tend to avoid having their photo taken to maintain their privacy while also acquiescing to zhan jie to an endurable extent to avoid offending them and to enlarge the size of their fan groups. Both idols and zhan jie deeply immerse themselves in this game because they cannot afford to hurt or lose each other. The game represents a public-private dynamic equilibrium with three different levels separated according to the conflict between idols and zhan jie (figure 1).

Figure 1. Public-private dynamic equilibrium process between idols and zhan jie.

[5.4] Hide and seek is the start of this game. Idols must hide their secrets, while zhan jie try to help peripheral fans understand their idols by taking pictures of them on every possible occasion and posting these pictures online. Since zhan jie must gain recognition from peripheral fans to obtain funds to continue pursuing their idols, they must constantly satisfy those fans' needs to reveal their idols' secrets. However, since most well-experienced zhan jie have seen their idols too many times, they no longer have a desire to reveal secrets about them. "We're a laofulaoqi [old married couple] now, and I enjoy the moments when I'm praised by other fans more than watching my idol," said one zhan jie with seven years of experience. Zhan jie collect personal information about their idols, such as flight numbers or hotel names, through unique means that are thought to be in a legal gray area. Idols sometimes change their flights before takeoff to avoid encountering zhan jie at airports or disguise themselves so as not to be recognized. Nevertheless, idols sometimes allow zhan jie to find them because they need their pictures to appear in fans' feeds. In this way, idols dominate the relationship by controlling the exposure zhan jie can give them.

[5.5] This hide-and-seek process occurs in every corner of idols' lives, although mainly at airports. Idols elaborately prepare themselves and dress up; zhan jie take pictures and post them on social media. However, idols occasionally disguise themselves by wearing sunglasses, masks, or hats when they do not want to be photographed. Zhan jie do not let their idols hide easily and are able to quickly find them in crowds, such as by waiting at a familiar airport gate and identifying their idols' assistants. The hiding and seeking happens rapidly when privacy and transparency are tolerable for both idols and zhan jie. These two processes are not in conflict; commonly, they occur together, with agreement from both idols and fans.

[5.6] The next level, trick or treat, begins when both sides start to feel uncomfortable. As zhan jie's activities begin to annoy their idols, the idols take certain preventative actions; when idols hide too much, zhan jie demonstrate their power over the idols' earnings. At this level, zhan jie may, for example, get too close at airports and knock their idols down or follow them into their hotels. Idols may then become annoyed and warn the zhan jie that they are angry, and if the zhan jie still do not change their behavior, the idols turn to social media platforms, posting articles that publicly request that the zhan jie restrain themselves. Some zhan jie follow their idols' instructions, although others refuse to do so.

[5.7] Meanwhile, zhan jie may become angry if idols hide too frequently. They believe their efforts help their idols enlarge their fan group; however, they may perceive that their idols do not appreciate them and even create obstacles to their activities. Consequently, they want to bring their idols out of hiding. Zhan jie use their influence over their idols' fan groups to strengthen their bargaining position as well; for example, they may organize fan support for the idols. The proof of this support is finally given to the idols at off-line locations, thus allowing zhan jie to show their idols how important their activities are for attracting and maintaining fans.

[5.8] This trick or treat is a trade-off between idols and zhan jie: when idols become angry, they play tricks on zhan jie, while zhan jie give treats to their idols. Both want to dominate the relationship and force the other to give in to their rules. Typically, this process ends with a return to the hide-and-seek level, although occasionally it escalates to the next level, which involves a conflict pattern.

[5.9] When idols and zhan jie no longer want to negotiate, the game reaches the last level: the ultimatum game. John C. Harsanyi (1961) first developed the ultimatum game, where two players allocate resources. One side puts forward a proposal, and the responder can choose to accept or reject it. If the responder accepts, they allocate resources using this proposal. If the responder rejects the proposal, both players receive nothing. Both players know the consequences of accepting and rejecting the proposal. In the final level of the game, idols and zhan jie act aggressively to inform the other party that they have entered the ultimatum game. At the preceding trick-or-treat level, idols and zhan jie mostly tolerate each other. However, sometimes, when excessive anger accumulates, conflict begins.

[5.10] When zhan jie are reprimanded by their idols at the second level, they often feel angry because they think idols take their efforts for granted. While they usually choose to take no action, they sometimes threaten their idols: zhan jie can influence whether their idol's public image is positive or negative because they have both beautiful and ugly photographs of them. Moreover, since zhan jie are very close to the idols, peripheral fans and the public trust what zhan jie say, even lies fabricated without any evidence. In such a scenario, zhan jie directly inform their idols about what they plan to do, such as by sending direct messages or giving them notes at airports.

[5.11] Idols may feel unsafe when their privacy is excessively invaded or they receive threats. Unlike zhan jie, idols usually seek legal means to protect themselves. They typically start by sending a lawyer's letter to warn the zhan jie again to minimize the damage to their fan group. A common belief among fan groups is that since idols rely on their fans, they should never hurt them. If the zhan jie do not change their behaviors, idols may consider calling the police or taking them to court to stop the invasion of their privacy.

[5.12] Idols and zhan jie have a showdown in the ultimatum game, which can lead to a horrifying defeat for one side. At the same time, the conflict makes both idols and zhan jie feel uncomfortable. This level involves a battle between both sides, through which idols declare uncompromising privacy boundaries to the zhan jie. In contrast, zhan jie ask for more public access. The battle's outcome depends on who accepts the other's proposal first.

[5.13] In China, zhan jie are frequently criticized by the public for invading idols' private lives. Some people believe they are no different from the paparazzi (Southern Metropolis Daily 2019). However, zhan jie do not agree: "We can be either artists or photographers, but not paparazzi," said one interviewed zhan jie with five years' experience. She explained, "The fundamental ideas are different. Paparazzi…tell stories about [idols'] private lives. They don't care how the photos look. Their photos are only taken to prove their stories are true. But we don't care about our idols' private lives; we only want beautiful photos and to enjoy our aesthetic work." However, zhan jie admit that they sometimes undertake illegal activities: "Those actions are agreed to by our idols. We actually have our own rules and ethics to ensure that we do not affect our idols' private lives. That is also how we distinguish ourselves from paparazzi."

[5.14] Through the game, a distance is decided between the public and the private. Although zhan jie take photographs, they still ensure the places they choose to do so are reassuringly public instead of photographing their idols in private places, which might make them feel uncomfortable. Zhan jie never intentionally disturb idols' work and always remain orderly when taking photographs in public spaces. They sometimes even help organize other fans to avoid being criticized by the public. These actions ensure their work is sustainable and that they can continue photographing their idols.

[5.15] Zhan jie also regard keeping idols' secrets as a significant responsibility. Sometimes, zhan jie may discover facts about their idols' private lives, such as accidentally witnessing private relationships. Once an idol declares they are in a romantic relationship, fans might feel betrayed and desert them (Galbraith and Karlin 2012; Zhao and Wu 2020); hence, zhan jie help idols conceal these relationships to help retain their fans. Zhan jie must also keep some good secrets. For example, if a contract (e.g., to a commercial or TV show) is revealed in advance, it might be canceled by the sponsor. Idols sometimes tell zhan jie about their contracts in advance; however, zhan jie must keep them secret so as not to threaten the agreements.

6. Emotional monetization: The embodiment of data fetishism among zhan jie

[6.1] It is difficult for zhan jie to get financial rewards for their work. Their initial motivation to create their fan station is to obtain aesthetic pleasure by photographing good-looking idols. Still, this aesthetic pleasure is not achieved directly by posting photographs; in fact, zhan jie often believe that aesthetic judgment must be recognized by the public, and their photographs can only reflect a high aesthetic level when they obtain popular approval. The most intuitive indicator of public recognition is Weibo post data, which provide the number of interactions with a post, or number of reposts, likes, and comments. Among these three indicators, based on our interviews, the most important is number of reposts, which means a user likes an image and chooses to share it with more people.

[6.2] Yiyi Yin (2020) points out that virtual data has become a fan object with strong emotional power, and various manipulations of data are important forms of fan practice. This also involves the emergence of a kind of data fetishism in the fan community, especially among zhan jie (Tamar and Zandbergen 2016). Data enable zhan jie and peripheral fans to understand each other's practices and quantify themselves. This quantification also enables zhan jie to constantly review the data volume of their own posts and strongly feel a concept of self (e.g., "my work is (not) qualified"; "I feel (joy) pain because of (high) low data"). Quantitative data show zhan jie the significance of their work, and they also publicly demonstrate this significance to others.

[6.3] Zhan jie not only consider their pictures' data volume but also make horizontal comparisons. Specifically, zhan jie with the highest data volume are often recognized as having the best aesthetic sense by fans. Acquiring the highest data volume brings a sense of victory to zhan jie, stimulating their eagerness for the next victory, while those who fail may become more competitive with the winner in the next competition. This process polarizes Zhan Jie, frequently resulting in conflicts. While levels of aesthetic taste among photographs are vague and immeasurable, the use of data makes zhan jie rankings authoritative and accurate, dividing zhan jie internally.

[6.4] There is a popular saying among zhan jie that "tong dan [fans of the same idol, here referring to other zhan jie] are the enemy." Hostility among zhan jie mainly originates from data competitions. Intriguingly, when the researcher asked the zhan jie about their daily routines, one with five years of experience suddenly said angrily, "[I] hate tong dan. Sometimes I hate tong dan so much and cry all day so I can't sleep at night." When the first author asked for her reasoning, she explained, "Because we have battles, we need to rush to send pictures. The first zhan jie who posts pictures on Weibo always gets the best data more easily. I am often angry about why tong dan exist. It makes it so painful and a struggle for me." She paused, then softened her voice and said, "Data is not important, right? In fact, it is just to satisfy myself—that is, to have good data, and [be] better than tong dan. Good data can make me happy, or we can say that good data equals happiness."

[6.5] As a zhan jie herself, the first author has a deep understanding of this zhan jie's statements. Zhan jie make every effort to pursue the best data, such as by taking pictures of the fan station. There are two zhan jie in the first author's fan station: one (the first author) takes charge of the photography, and the other is responsible for editing the pictures. The first author has been asked by her partner to call her immediately after taking photographs to post the pictures as soon as possible and thus get good data. If a zhan jie is not satisfied with the pictures she has taken, even if she has already taken pictures on the spot, she may buy more pictures from a dai pai and choose the best ones. These methods allowed the Weibo account of the first author's fan station to have the most followers of their idol, as well as be ranked first in the year-round data. Other zhan jie feel that they can't get satisfaction from the idol, so they choose to leave the fan community. Three years ago, when the first author just entered the zhan jie industry, her idol had eight fan stations; now, only the first author's fan station remains.

[6.6] Data allow zhan jie to clearly determine whether their work is good or bad, whether they are recognized by peripheral fans, to what extent they reflect their idols' beauty, and how they compare with other zhan jie. However, the core of a zhan jie's work is "shaping beauty," a concept that is difficult to define or quantify: "The algorithm computes the affective codes of data first by bonding them to individual achievement, and also by providing action spaces for fans to play with it. Consequently, the practice of data contribution is constructed as a quantification of affect" (Yin 2020, 481).

[6.7] Fans are not ignorant of zhan jie's desires for good data, so peripheral fans consciously perform data labor for their favorite zhan jie, that is, contribute data for idols. This is common in many fan communities as well as those of zhan jie, as peripheral fans hope that their favorite zhan jie will then be satisfied and stay in the community. This kind of data laboring may sometimes even be organized by a special fan data team composed of peripheral fans and that has a certain set standard in terms of making data. For example, no matter which zhan jie, each Weibo post must reach one hundred reposts; better pictures should reach at least five hundred reposts; and pictures from the zhan jie you like most must reach one thousand reposts. Sometimes, to please a zhan jie, peripheral fans even hire programmers to write scripts that automatically repost for the zhan jie.

[6.8] Due to the existence of data in the data team, zhan jie have a more quantitative judgment standard for their own data. In addition to a horizontal comparison with other station sisters, the amount of data interaction on Weibo (reposts, comments, and likes) can also affect a zhan jie's mood. They realize that if a Weibo post doesn't receive one hundred reposts, the picture is considered particularly ugly by the fan community, while if it has between one hundred and five hundred reposts, the fan community considers it average. Only when a photograph's data reaches more than one thousand reposts can a zhan jie feel an extra sense of achievement. Therefore, zhan jie have begun to issue requirements for peripheral fan data: if the interaction volume on a Weibo post that a zhan jie has worked hard on does not meet expectations, they will complain to peripheral fans, believing that they do not appreciate the post.

[6.9] In short, data has formed a common currency that circulates among peripheral fans that also impacts the emotions of zhan jie, a fundamental driving force of their work. Through the conscious contribution of data, peripheral fans give zhan jie meaning in taking pictures of idols. Data has therefore become equivalent to the massive emotional power that both groups can understand and quickly grasp, which changes a zhan jie's professional life and allows them to obtain continuous emotional feedback in their professional career and supports them in their future work.

7. Bonding idols and fans: Zhan jie as mediators

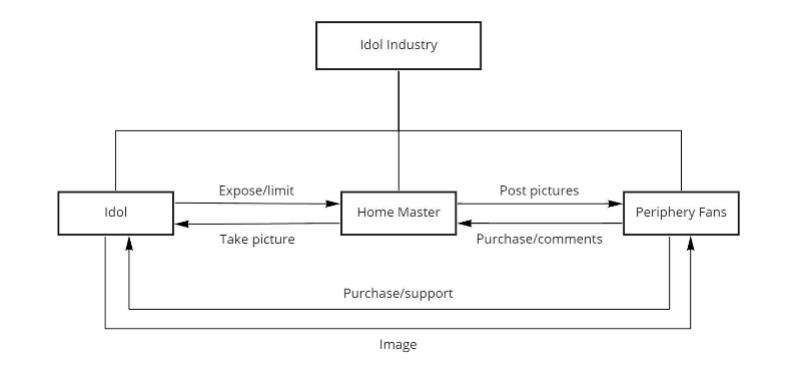

[7.1] According to Matt Hills (2005), fans must seek continuous stimuli to maintain their passion for their idols. Meeting idols face to face is every fan's dream; however, most cannot attend every off-line event to see their idols in real life and must experience "materials" (Wu Liao) for stimulation. Materials are things related to their idols that can arouse fans' enthusiasm by depicting their idols' good looks or personalities (Fiske 1992). Traditionally, materials such as promotional photos, vlogs, and TV show appearances are provided mainly by official organizations (Marwick 2013). Nowadays, fans can also produce self-made materials such as photos, videos, and drawings. When fans are sufficiently stimulated, they stay loyal to their idols (Liang and Shen 2016); therefore, materials are particularly significant for the relationship between idols and fans (figure 2).

Figure 2. Idol industry landscape.

[7.2] "Producer" (chan chu) is the name given by fan groups to fans who make fan-made materials. Among these producers, zhan jie (photographers) are at the top of the pyramid. While fan-made videos and drawings are derived from existing materials, zhan jie can provide new materials by photographing their idols off-line (Sun 2020), a unique characteristic that make zhan jie critical to bringing fans and idols together.

[7.3] A two-month production period might be required for a TV show from recording to broadcasting, causing an inconvenient moment for idols: they are working, but fans do not have the materials to enjoy and may abandon them accordingly. Zhan jie solve this problem by photographing their idols in airports and on the way to TV stations. When they post those photographs, fans can see their idols online and remain stimulated without needing to view official materials or visit locations in person. Zhan jie are therefore prominent agents in making direct links between idols and fans. Unofficially, zhan jie produce idol pictures routinely and professionally, making them an essential bond between idols and fans.

[7.4] Although zhan jie form an important bond in the fan community and often stabilize fans' relationships with their idols, this does not mean that zhan jie themselves have a stable position. In fact, since the Qinglang movement, an increasing number of zhan jie have quit. According to one zhan jie with seven years of experience, the Qinglang movement has not had too much of a negative impact on the work of the zhan jie. For example, the act of photographing is not highly regulated: "Qinglang is mainly aimed at fan communities, such as no longer allowing the existence of rankings so that fans don't have to continue to do data labor, or strictly censoring fights between fan communities. Since we don't need to participate in fan community activities, Qinglang doesn't really affect us too much." At the same time, she did not deny the fact that Qinglang has caused many zhan jie to leave the business: "We get aesthetic fatigue very easily, mainly because we have seen idols too many times. The government has banned all idol talent shows, which means that it is hard to know new idols, making it impossible for zhan jie to have the next idol to pursue after they get bored with the previous one, so they don't want to be a zhan jie anymore." She also admitted that zhan jie are scared of being persecuted under the Qinglang movement, as they fear that the Chinese authorities will punish them in the future.

8. Conclusion

[8.1] We observed and contextualized the position of zhan jie in Chinese fandom culture, which revealed the process in which zhan jie scramble for public-private spaces with idols while also bringing idols and fans together. We considered zhan jie to be professionals within fan groups instead of a simple interest community. Through our analysis, we drew a new landscape of the Chinese idol industry. Core fans transform other fans' positions in the idol industry by securing the rights to produce merchandise related to idols instead of simply editing videos from official sources. We thus conclude that the relationship between idols and fans is not linear, as core fans such as zhan jie significantly mediate this relationship, with all existing in a mutually beneficial symbiosis. Moreover, while there are many games played in this relationship, the process is often gentle: idols tend to accept and appreciate zhan jie, and zhan jie respect and worship idols. The eventual outcome of such a relationship usually results in an idol gaining more fans, especially when the idol does not perform public activities to maintain their fans' loyalty, while zhan jie gain more attention and compliments from the fans and prominence within the fan community.

[8.2] We further challenge the idol-fan dichotomy in East Asian fan studies by situating zhan jie, who are productive fans, as mediators and indicate their important role within the idol industry. While zhan jie are obliged to show the beauty of their idols to all their fans, this also demonstrates a predatory nature within fan groups toward the objects they love. In particular, zhan jie always invade their idols' lives and work within the limits of flow and appropriateness (a self-judgment stipulating that they must not affect the idol) to obtain primary materials sufficient for idol industry production. Common knowledge and extensive fan research always assume that general fan groups serve their idols willingly and establish harmonious relationships with them (Lamerichs 2018; Sun 2020; Tan 2020; Weizhi Finance 2020), yet our findings reflect another common but unrecognized situation: zhan jie, as important parts of the idol industry, always perform their own identities by penetrating into their idols' lives. However, this penetration is beneficial to both idols and peripheral fans and is therefore tacitly accepted and flourishing within the Chinese idol industry.

[8.3] The entire process of interaction among zhan jie, idols, and fans forms a delicate and balanced cycle that relies entirely on the Chinese idol ecosystem and digital platforming. Idols must embody enough characteristics to avoid losing fans, while zhan jie must gain the praise of peripheral fans (followers, likes, reposts, and comments), gauging the value and responsibility for production. Yiyi Yin and Zhuoxiao Xie (2021) discuss how the actions of Chinese fans on digital platforms create "platformized language games" that fans and idols experience and participate in together. These researchers also point out that the various interactions of fans on digital platforms, such as deliberately creating data flows and intentional praise discourses, ultimately create what Hills (2016) refers to as a currency for group communication, belonging, and supporting personal recognition. This process of interaction allows fans to gain a sense of identity, satisfaction, and even a certain internal status within the fan community. In this study, data is this currency that cultivates the emotions acted upon by zhan jie, who actually participate in this platform game: they acquire raw material in the form of their idols' pictures through a game of hide and seek, actively process the material, and then post it on social media, enjoying praising discourse and data laboring from peripheral fans. In turn, other fans become closer to their idols due to the pictures that zhan jie post.

[8.4] Yin (2020) views data flows as important emotional objects in the Chinese fan community, connecting fans with various objects and substances. The same applies to Zhan Jie. We found that while zhan jie lose their strong admiration for idols due to their long exposure to them both in physical and virtual spheres, the data labor fans show for idols' pictures create new emotional attractions for zhan jie. Data flows are not only tied to peripheral fan actions, as Yin (2020) suggests, but are also embedded in zhan jie's emotional labor, replacing idol worship as the driving force of their free (nearly no additional revenue) and passionate fan labor. The data contributions demonstrated by peripheral fans whom xhan jie have encountered, such as post popularity and account follower numbers, are important indicators that quantify how well the zhan jie have worked. Unlike peripheral fans, who are the main subject of Yin's (2020) research, we conclude that the emotional power triggered by algorithmic flows further drive zhan jie's productive activities, making them take risks to intrude into their idols' lives and work and shaping other relevant economic industries, ethical norms, and behavioral practices within the zhan jie group.

[8.5] Research on Chinese fans has always focused on the binary relationship between fans and idols, and while Chinese fan studies have increasingly focused on the role of algorithms and datafication in the fan community and fans' emotional economy, they remain within a binary framework and do not introduce other types of fan entities apart from ordinary fans. We thus introduce zhan jie, a particular group that is critical to and thriving within the Chinese fanosphere, as an exploratory participant observation attempt to study productive fans in China. We encourage a view of the Chinese fan community as fluid rather than frozen, where zhan jie's game of hide and seek with their idols is not a rigorous ritual or procedure but a comfortable offense, with the two interacting and exploring each other's boundaries. We also encourage fan studies scholars to focus on new types of emotional currency employed by fans, with data contributions brought by peripheral fans, as suggested by Yin (2020), rather than zhan jie's admiration of idols triggering their primary productive labor. This concept will guide future Chinese fan studies scholars toward the mediating forces in the idol industry, including the emergence of a kind of data fetishism, rather than direct fan-to-fan or fan-to-idol emotions.

9. Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Associate Prof. Dr. Wang Rui from the Communication University of China for his invaluable guidance and assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Our appreciation also extends to the anonymous reviewers and editors whose feedback greatly enriched the quality of this work.