1. Introduction

[1.1] Over the past few decades, fandom has grown in terms of mainstream awareness and social acceptability. Many people have previously been embarrassed or even ashamed to admit that they participated in fan activities like attending fan conventions or reading or writing fan fiction. Though some level of stigma persists, a recent cultural shift has made many fans feel more comfortable expressing their fan identities publicly (Stein 2015). Young adults, in particular, have more opportunities to connect through social media with others who love a show or book just as much as they do. As fan fiction becomes more prominent, it becomes more important to understand these young fans' behaviors while participating in fan spaces. With more comprehensive tagging and search systems, fan fiction may be easier for these young readers to find. The methods they use to search for fan fiction could help improve library services and support for this demographic. In this article, I address the following questions: (1) How do young adults find fan fiction to read? (2) How do young adults find fiction to read? and (3) How do the methods that young adults use to find fiction and fan fiction differ?

2. Literature review

[2.1] Case and Given (2016) define information behavior as "the ways that individuals' [sic] perceive, seek, understand, and use information in various life contexts" (3). This includes a wide range of ways people engage with information, including information seeking, which they define as "a conscious effort to acquire information in response to a need or gap in your knowledge" (6). Information seeking is one part of information behavior, which can also include other behaviors that are not conscious, such as encountering information "through serendipity, chance encounters, or when others share information that they believe may be useful to you" (6).

[2.2] Fans are "an information-intensive group" with "sophisticated practices…in organising and sharing information" (Price and Robinson 2016, 661), so it is no surprise that these fans created their own processes and practices in response to their need to organize and share information (Hill and Pecoskie 2017). There are many similarities between the practices that fans use to organize fanworks and those used in the field of library and information science (LIS). The main differences are the terminology used to refer to these practices and the actual functionality of the resulting databases or catalogs. For example, where library staff catalog, volunteers on Archive of Our Own "wrangle" tags (Koven-Matasy 2013, 31). Moreover, fans' practices are not just similar to their professional equivalents; they are often on par with them (De Kosnik 2016; Hill and Pecoskie 2017; Koven-Matasy 2013). As such, examining fans' practices and fan responses to them could inform the future of library and information science and help the field make their databases, catalogs, and websites more accessible in the digital age.

[2.3] However, although the link between fans and information was made decades ago, research about fan information behavior has been sparse (Hart et al. 1999; Hills 2002; Jenkins 1992). Little research has thus far been carried out on the information behaviors of teen and young adult fans. Although Waugh (2019) has examined the types of information teenage fans sought within a fandom space, there has been no focus on how young fans are searching for information or how those search experiences may shape their overall search literacy skills. My aim is to begin to fill this gap and examine the information-seeking behaviors of teenage and young adult fans.

3. Methods

[3.1] In this pilot study, ten semistructured interviews were conducted with participants from the United States aged eighteen to twenty-three. These participants were recruited via posts on Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, and various Discord servers. Participants indicated their interest in the study using a Google form, and the first ten respondents were contacted. If a respondent did not reply within approximately 48 hours, the next respondent on the list was contacted. The interviews were done one-on-one over Zoom. Interviews lasted between fifteen and thirty minutes on average. All participants have been assigned pseudonyms to ensure their anonymity.

[3.2] Funding for this study was provided by the University of Maryland’s College of Information Studies, which supported my work by awarding me a Research Improvement Grant. This funding was used to compensate each of my participants with a $20 Amazon gift card. One participant declined compensation. The funding also paid for premium access to Otter.ai, which was used to transcribe the interview recordings.

4. Reading habits

[4.1] All participants had begun reading fan fiction by the time they graduated from high school. The majority of them discovered fan fiction in high school, though one participant stumbled across it as early as elementary school. Half of the participants (50 percent) discovered it serendipitously while an additional four (40 percent) were introduced to it by friends.

[4.2] Though the participants had been reading fan fiction for multiple years at the time of the interviews, an overwhelming majority (80 percent) said they read fan fiction at least once a week. Many noted, however, that this frequency depended on factors such as their school or work schedule or the current pandemic. Six participants (60 percent) referred to reading, whether fiction or fan fiction, as a form of escape or stress relief. In fact, four participants (40 percent) noted that they were reading more fan fiction due to the pandemic, and five participants (50 percent) reported reading more fiction than before. Interestingly, while fan fiction is, by default, a digital form of content, half of the participants (50 percent) said that they preferred physical books when reading fiction. Three participants (30 percent) had no preference, and only two (20 percent) said that they preferred to read e-books. While print fan fiction does exist by way of fanzines, print-on-demand services, and fanbinding (the practice of printing out and binding fan fiction DIY-style), the vast majority of fan fiction is only found in digital formats. However, some participants indicated some level of separation between reading fan fiction and fiction and spoke about them as though they were entirely different hobbies. This distinction in the participants' preferences for the format of their reading materials could be acting as a separation: print for fiction and digital for fan fiction may help them to keep their two reading hobbies distinct.

5. Search Strategies

[5.1] The mediums that participants used for reading fiction and fan fiction (print and digital) also affected their search strategies. Each participant was asked to explain how they would go about searching for a new work of fiction or fan fiction to read. These answers were then categorized into three types of browsing as described by Marchionini (1995): directed browsing (searching systematically, often for a specific work known to them prior to beginning their search), undirected browsing (searching with little purpose or intention in the hopes of stumbling across something interesting), and semidirected browsing, which lies somewhere between the two (searching somewhat systematically and without a concrete target) (106). Though participants described directed browsing for fiction and fan fiction, they were more likely to diverge when it came to the distinction between the two. When searching for fiction, participants were more likely to use undirected browsing, during which they were not looking for anything specific and simply walked around a bookstore or library and picked up anything that caught their eye. This also held true when they were searching for e-books, with one participant, Vasya, noting that she would scroll through the free books on Amazon Prime Reading until she found something that she wanted to read. On the other hand, participants were more likely to use semidirected browsing for fan fiction. Their search process was thus more systematic. Participants described using tags, filters, and keywords to search for exactly the kind of stories they wanted to read. Another participant, Arwen, described this process: "You go to your preferred site, and you are looking for that and you're looking for this thing. Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. You can say exactly what you want, and it'll try and match." This is a stark contrast to the way she finds fiction to read: she mostly relies on recommendations from others and undirected browsing at bookstores or the library.

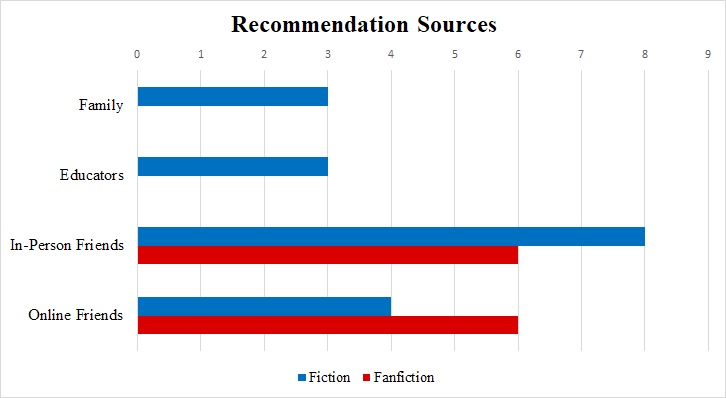

[5.2] In terms of reading recommendations (figure 1), participants were equally likely to get recommendations from online or in-person friends when it comes to fan fiction. However, they did not name coworkers, educators, or family members as recommenders of fan fiction, and one participant, Marinette, even said, "I don't tell too many people that I’ve gotten into fan fiction," as she felt it was embarrassing or "cringey." On the other hand, participants were more likely to get fiction recommendations from people they knew in person in all categories. Participants named different family members, professors, coworkers, and friends as sources of recommendations. Participants were also less likely to receive fiction recommendations from online friends whom they didn’t know in person. While fandom remains a social hobby and some aspects of it have crossed over more firmly in the mainstream, there still exists at least some level of perceived stigma around talking about fan fiction with anyone other than friends or strangers on the internet.

Figure 1. A graph showing the sources participants consulted when looking for recommendations for fiction and fan fiction.

[5.3] Platform-wise, Archive of Our Own was the clear winner of the popularity contest, with seven participants naming it as one of their go-to websites for fan fiction. Tumblr and Fanfiction.net were named by three participants each, and one participant consumed fan fiction only in the form of audiofics (audio readings of fan fiction) on YouTube. When asked why they preferred the platforms that they frequented, many participants listed criteria such as organization, searchability, tagging systems, and popularity of the platform as being important to them. Many participants praised AO3's comprehensive tagging and filtering system, which was the criterion most commonly cited by participants. This sort of search system can make semidirected browsing much easier, as there are ways to filter out options they do not wish to see and to streamline the search process.

6. Ease of searching

[6.1] When asked whether they thought it was easier for them to find fiction or fan fiction to read, participants overwhelmingly responded that fan fiction was easier to find. Only two participants (20 percent) answered that books were easier to find. One factor that came up repeatedly in response to this question was the amount of information the participants had access to about a work prior to beginning to read it. "I wish real books came with the AO3 tagging system, but unfortunately, they do not," said one participant, Juliet.

[6.2] Two participants (20 percent) highlighted frustration with browsing libraries and library catalogs. "I don't really have that second nature feel for, like, walking around a library or whatever," said Megatron. Similarly, searching library databases frustrated Minerva. Other participants also alluded to this when they discussed why fan fiction was easier to find than fiction. Being unable to simply search for exactly what they wanted to read, such as a certain trope, made the library database search process more difficult for them. Unfortunately, they are not alone. Libraries can be perceived as less user-friendly to search, which can lead patrons to feel overwhelmed and give up (Case and Given 2016).

7. Discussion

[7.1] One of the main findings from this pilot study is that, put simply, these readers want more information. While they can get a fairly good idea of what is in store for them by glancing at the tags on Archive of Our Own, they experience frustration when the same cannot be said for library catalogs or book covers. As quotes from reviews take up space on the front and back covers of books, actual information about the content takes more effort to find, such as opening a book to read the inside book flap or flipping to the copyright page to find a short summary. While high-level options like entirely redesigning library catalogs have the potential to aid with this problem, they are unlikely to be implemented due to important factors such as time and cost, both on the end of the developers and the libraries, who would need to adapt to such a system. However, there are some options that could be executed immediately.

[7.2] When recommending a book to patrons, library staff could include information such as the length of the work, some of the tropes, the kinds of relationships, content warnings, or other important thematic data points. In other words, if you would tag it on AO3, include it in your reader's advisory. This information could also be included in LibGuides and recommendation lists in general. Additionally, trope-themed book displays or recommendation lists (e.g., "enemies to lovers," "slowburn," "found family," "accidental baby acquisition"), as some libraries and publishers have already begun to compile, could be a great way to help these readers find fiction that interests them.

8. Conclusion and future work

[8.1] Though there has been an increase in scholarship on fans and information in recent years, there is still much work to be done, particularly in regards to young adults' experiences in fandom and their interactions with information. This study was a pilot version of one I hope to conduct in the future on a larger scale with participants from a broader age range, which would include teenagers as well. The future version of this study will dive deeper into participants' motivations and focus on some of the key differences in information-seeking behaviors that were noted above. Going forward, I hope to continue addressing this gap in the research and further develop our knowledge of the information-seeking behaviors of young readers.