1. Introduction

[1.1] Contemporary popular cultural productions quite commonly lead fans to read and ponder real-world historical figures and backgrounds. For instance, exerting "a powerful and inexorable influence" on people's general interests in history (Hower 2019, 78), the historical series The Tudors (2007–2010) led fans to conduct "detective-like inquiry work" to analyze Henry VIII's actual biography and other unfamiliar historical topics behind fictional depictions (Matthews 2016, 4). Similarly, fans of the historical fantasy show Game of Thrones (2011–2019) or the time-travel series Doctor Who (1963–1989, 2005–) often question the historical accuracy of the plots while reviewing how contemporary popular narratives present the past and its sociocultural norms (Matthews 2018, 225; 2020). Despite the paucity of scholarship on this topic, these practices are prevalent in fan communities across all genres and in many cultures.

[1.2] These history-related devotions show a particular type of historical poaching conducted by fans (Matthews 2018, 225). Akin to scholars of reader response theory, who argue that reading is a creative process (e.g., Iser 1972; Radway 1983; Ross 1999), fans critically construct their understandings of history based on their own experiences and knowledge, including the content in shows or movies that resonates emotionally with them (Metzger 2010, 132). However, these fans rarely practice historical revisionism (Krasner 2019, 17) to reinterpret what actually happened in the past or to revise historical records. Fans instead emphasize how the abstract historical or political concepts are reimagined to suit current popular cultural norms and to produce their own fantasy creations (De Kosnik 2017, 270; Duncombe 2007). Accordingly, "history is poached like texts in popular culture" (Matthews 2018, 226), comparable with the way fans critically appropriate a fictional show, novel (Jenkins 1992), or celebrity figure (Linxi 2020). Further, fandoms' digital media context increasingly encourages such collective poaching practices; while fans more frequently demonstrate and discuss their ideas online (Matthews 2016), related information is produced and consumed among fan communities (Price and Robinson 2016).

[1.3] On this basis, I study historical poaching—using Matthews's (2018) definition—in celebrity fandom, exploring how fans rethink their fandom-related histories and how these processes interact with their celebrity understandings and community practices. As a portion of a broader project exploring contemporary Chinese celebrity fans' behaviors, this research investigates representative fan groups of two Chinese musical actors, Ayanga and Yunlong, who have been friends since college and often collaborated when they first became well known in 2019. Based on unobtrusive observation of one hundred active fans on the Weibo social media platform and sequential semistructured interviews with thirty individual fans, this paper discusses two history-related cases in these fans' practices. The cases of Yunlong and Ayanga show two different historical poaching focuses—the first case (the Yunlong-Guangxu emperor connection) demonstrates how fans relearn and reimagine a historical figure and then broaden their celebrity understandings based on what they learned, and the second case (Ayanga's Mongolian cultural heritage) shows how fans apply historical understandings to promote their fandom beliefs and support their community practices. I conclude that celebrity fans are not concerned with general historical reinterpretations, accuracies, and perspectives but rather in using history as a means to further enhance and/or validate their current celebrity fandom; in this way, fans' poaching practices are centered by their fandom focuses. Emphasizing fans' own perceptions and concerning myself less with separating historical facts from fans' discourse, my research provides potential insights into further explorations of how historical poaching practices and celebrity fandoms intersect.

2. Rethinking the Guangxu emperor and his connection to Yunlong

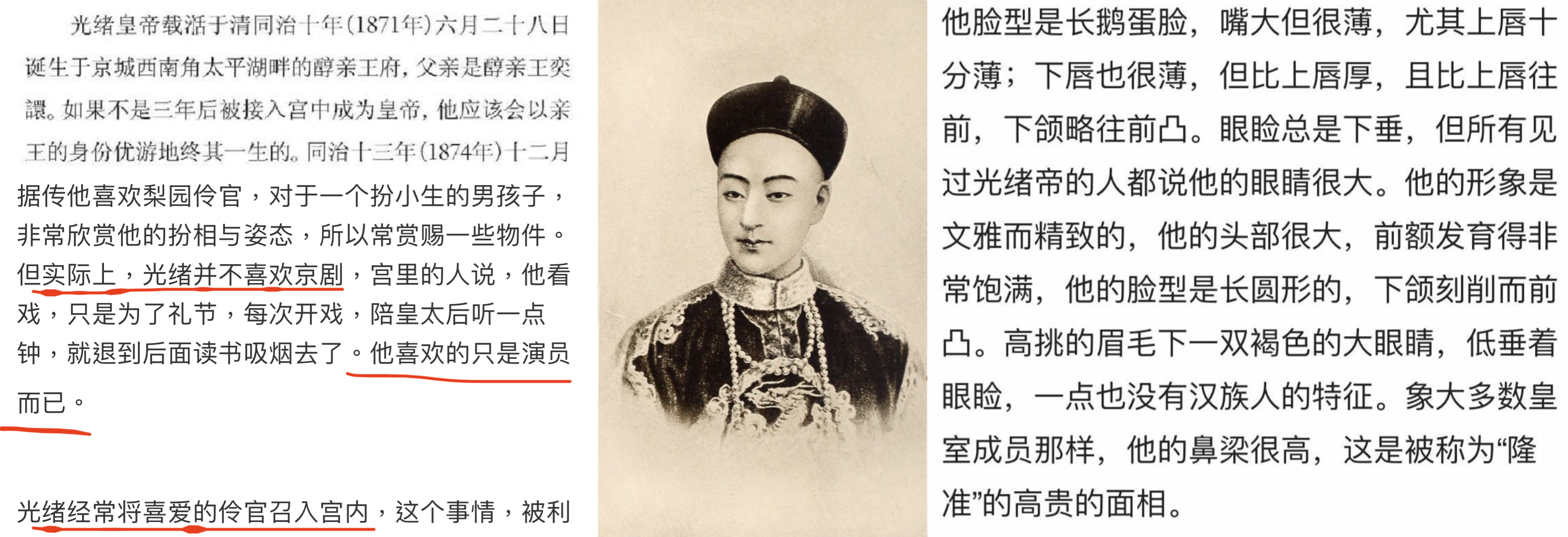

[2.1] Fans' poaching of the Yunlong-Guangxu connection began in 2019, when Yunlong played the Guangxu emperor (1871–1908) of the late Qing Dynasty in a recurring theater show, Derling and Cixi (figure 1). Set in the late 1890s, this show is based on accounts of Qing Princess Derling (1885–1944, a nobility member who received a western education); Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908, a dictator who effectively controlled the Qing government from 1861 to 1908); and the Guangxu emperor who was depressed and put on house arrest by Cixi in 1898. Prior to this play, many of Yunlong's fans appeared to adopt the common view of Guangxu as a naive and powerless emperor who failed to strengthen or reform the country in his early reign and then completely lost power. Aiming to better understand Yunlong's performances of Guangxu and satisfy their own curiosities, fans actively sought historical materials documenting this emperor's unfamiliar personal traits and stories and shared them on Weibo (figure 2). Such discovery posts allow fans to collectively make connections between Guangxu and Yunlong, such as their similar looks and their birthdays, which are only one day apart. Fans who believe Yunlong and Ayanga are romantic partners have been most excited about Guangxu's potential queerness; some documents state that although Guangxu did not like operas, he adored a male actor very much, and he and one of his wives often wore each other's clothes. Although the majority of these claims can be supported by my survey of multiple historical studies (e.g., Huang 2013; Kwong 2000; Liang et al. 2019; Pan and Liu 2011), fans often have posted them as photos or screenshots without any references, while others also barely question the sources or the credibility during their discussions.

Figure 1. Selected stage photos of Yunlong in the theater play Derling and Cixi (posted by the show's official accounts on Weibo).

Figure 2. Selected fans' discoveries on Guangxu's partial biography, same-gender affection, and appearance (Weibo).

[2.2] Celebrating the Yunlong-Guangxu connection has allowed fans to develop a deeper understanding and empathy for Guangxu and to reimagine this historical figure in their minds. For example, many fans have changed their attitudes about Guangxu—from judging him for his failure to feeling sorry for him—when reading the literature that describes the supposedly happy and easy life he would have had as a regular member of the nobility if he had not ascended to the throne at the age of four; some fans even post about how they cried while reading Guangxu's biographical records. Relearning Guangxu's historical background also leads fans to recognize that the Qing government was doomed to end and could not be saved by a single emperor with limited power. Nonetheless, these new perceptions rarely encourage fans to retell the history of Guangxu or to review the historical accuracy in Derling and Cixi, because fans mainly focus on reimagining a Guangxu character that combines such historical understanding with their celebrity fandom. Creating fan art and fan fictions around this Guangxu using Yunlong's look and personality traits, fans also extend their empathy to this character, such as referring to him as Tiantian (a nickname based on Guangxu's personal name Zaitian). Guangxu's potentially queer relationship with his alleged favorite opera actor is also poached by fans who imagine a real-world relationship between Yunlong and Ayanga.

[2.3] Meanwhile, the Guangxu-Yunlong connection also provides fans with a new lens to interpret and fantasize about Yunlong. Many fans value the similarities between Guangxu and Yunlong, perceiving these coincidences as proof that Yunlong was destined to play this Guangxu character. Fans have also broadened their understanding of Yunlong through reading his interviews and Weibo posts (figure 3) that illustrate how he interpreted Guangxu and crafted his performances. Fans combine this information with their established Guangxu character and imagine how Yunlong would have felt Guangxu's pain; they also imagine how he might have had a conversation across time and space with this emperor, bringing fans closer to Yunlong on a spiritual level. Analyzing Yunlong's performances in Derling and Cixi also allows fans to evaluate and applaud his professional devotions and acting skills. In general, as fans' research has allowed them to perceive Guangxu in their minds as both a clearer historical person and then an imagined character, their discoveries and fantasies, in turn, enable them to understand and connect to Yunlong on a broader and deeper level.

Figure 3. Yunlong's interview and Weibo posts illustrating how he wants to preserve a memory and how he understands Guangxu's struggles (posted by NCPA and Yunlong on Weibo).

3. Rethinking China's Yuan Dynasty and Ayanga's Mongolian Chinese heritage

[3.1] As a Mongolian Chinese celebrity, Ayanga's cultural and ethnic heritage is often promoted by media corporations and fantasized about by fans. It is quite common to see Ayanga wearing traditional Mongolian clothes or presenting photos of himself in such outfits at shows and galas (figure 4) while answering culturally related questions and demonstrating his Mongolian speaking and writing abilities; one commercial starring both Ayanga and Yunlong also emphasized several typical Mongolian activities for promotion (figure 5). Such cultural representations encourage his fans to further wonder about and discuss his ethnic experiences, personality traits, values, and skills—fans will post about whether Ayanga's Mongolian heritage has nurtured his singing and dancing talents, for example. These cultural characteristics also contribute to fan creations, especially by fans who fantasize about Ayanga and Yunlong's romantic relationship. One popular fictional plot posted on Weibo is an imagining of Ayanga as an emperor of the Great Yuan (1271–1368, China's one dynasty established by a Mongolian clan) and Yunlong as the one who keeps Ayanga from being a wise monarch—the empire eventually collapses because of their relationship.

Figure 4. Selected photos of Ayanga wearing Mongolian clothes on shows and at galas (posted by Ayanga on Weibo).

Figure 5. Moments in the commercial video when both actors shepherded, performed historical costume shows, and practiced Mongolian archery (posted by the commercial's official account on Weibo).

[3.2] However, this particular fan-fictional historical poaching attracts criticism on Weibo from some fans who exclusively love Ayanga and consider such an imagining disrespectful to Ayanga's cultural heritage. These exclusive Ayanga fans argue that it should be common knowledge that it is impolite to speak of the Yuan dynasty—especially its destruction—in front of a Mongolian Chinese person who loves their ethnicity and culture, such as Ayanga. Supporting this claim, a few Mongolian Chinese fans express how they indeed feel uncomfortable reading this fictional plot. Although acknowledging that the fiction is only a fandom practice, these exclusive fans still believe such fan creations would also damage Ayanga's pursuit of promoting Mongolian arts and culture; thus it is righteous for them to criticize such creations and report them to the Weibo platform.

[3.3] These allegations receive strong reactions from fans who enjoy and support this fan-fictional plot. One central argument is that the Great Yuan dynasty collapsed more than six hundred years ago, and fans often post photos of textual documents stating the Yuan dynasty's history as simple proof. Other fans further comment about how they think the Great Yuan was a terrible government that favored violence and discrimination and would only ever have lasted a short period. Meanwhile, these fans declare that these discussions are also not a denial of those earlier Yuan emperors' contributions and glory. Fans further argue that contemporary Chinese people would not feel attached to the Yuan dynasty or regret its destruction; they even challenge those Ayanga-exclusive fans to personally ask for Ayanga's opinions on this matter. This argument is also defended by another group of Mongolian Chinese fans who testify that neither they nor their family members would have any negative reactions to the statement: "The Great Yuan has collapsed."

[3.4] Although fans' debate on Weibo originated from the subjects of the past Yuan dynasty and Ayanga's Mongolian Chinese cultural heritage, it soon shifts toward their own fan community identities and values. For instance, fans who support such fictional plots tend to accuse Ayanga-exclusive fans for caring about history only as an excuse to start a fandom war because they hate to see Ayanga and Yunlong paired together. Meanwhile, exclusive fans also announce that these fan-fiction authors and supporters never respect or truly care about Ayanga but use his image only to build such fantasies. In general, fans on both sides appear to be much more passionate about criticizing each other's agendas and proving their own community righteousness than they are about evaluating the Yuan dynasty's historical facts and aspects of the Mongolian Chinese heritage.

4. Poaching history for existing celebrity fandom focuses

[4.1] Fans' historical poaching, in both cases, is not explicitly intended to retell a particular piece of history but rather centered on enhancing their already existing fandom investments in Ayanga and Yunlong. It is apparent that fans are far less concerned about historical accuracies or perspectives; for instance, fans who fantasize about the Yunlong-Guangxu connection show good faith in the credibility of the uncited historical discoveries, as long as they resonate with fans' fantasies and understandings. Fans who argue about the Great Yuan dynasty also emphasize the importance of selecting historical pieces that support their position and soon shift their focus from discussing the history to disparaging each other's agendas. Additionally, although fans neglect the political concepts in these historical periods, their poaching practices undeniably relate to contemporary political aspects that fans believe are important to their celebrities—the potential queerness (Yunlong) and the Mongolian minority heritage (Ayanga). These poaching practices also present a key difference from those of The Tudors or Game of Thrones fans, who begin viewing the fictional depictions and then poach historical texts for review or reconstruction of that fiction. Ayanga and Yunlong's fans, choosing specific historical pieces upon which to build original fictional plots and understandings of their celebrities, poach history only to comply with and reinforce their already existing celebrity fandom beliefs rather than challenge or fundamentally change them.

[4.2] In the cases of Yunlong and Ayanga, fans' relatively contrasting practices—caused by different fandom focuses—are another demonstration of how fans centralize their current celebrity fandom during historical poaching. Fans who enjoy the Yunlong-Guangxu connection have fewer conflicts with each other because of their concentrated attention and similar perceptions, leaving space for fantasies and reimagining. Just as the specific connection between Guangxu and Yunlong provides fans a clear target to discover and reimagine, fans' shared views of Yunlong's looks and personal traits also produce less divergence when they apply his image to such fantasies. Further, in the process of enhancing their interpretations of Yunlong's professional skills and devotions, fans tend to focus on their own personal connections with Yunlong and support each other's practices. By contrast, fans' poaching of the Great Yuan dynasty is accompanied by constant arguments, encouraged by their preexisting community differences and hostilities. These groups of fans—those who exclusively love Ayanga and those who love both Ayanga and Yunlong—regularly clash because of their different but persistent beliefs about Ayanga (especially concerning whether or not he and Yunlong are enemies or intimate partners). Thus, as fans poach the Yuan dynasty in ways that center on their differences, they can easily challenge each other's diverse perceptions and trigger arguments. Fans then divert their poaching focus from building fantasies to producing evidence in support of their own reasoning, as the validation of their beliefs and the victory of their side is more significant on account of their long-standing community issues.

5. Conclusion

[5.1] These two cases show that historical poaching by Ayanga and Yunlong's fans rarely concerns actual historical reinterpretations, accuracies, or perspectives; instead, these fans focus on how they can manipulate historical pieces to enhance and/or validate their current celebrity fandom. While the first case (the Yunlong-Guangxu connection) demonstrates fans' emphasis on building fantasies and interpreting the celebrity, the second case (Ayanga's Mongolian cultural heritage) is mostly propelled by persistent fans' desire to perpetuate their differing perceptions of the fantasy and to continue their preexisting community conflicts. As they conduct poaching practices that validate their fandom beliefs, fans pay less attention to how these practices might also influence their general historical perceptions of certain figures and periods. With these findings, I aim to provide potential insights into the interaction between celebrity fandoms and fans' historical poaching practices.