1. Introduction

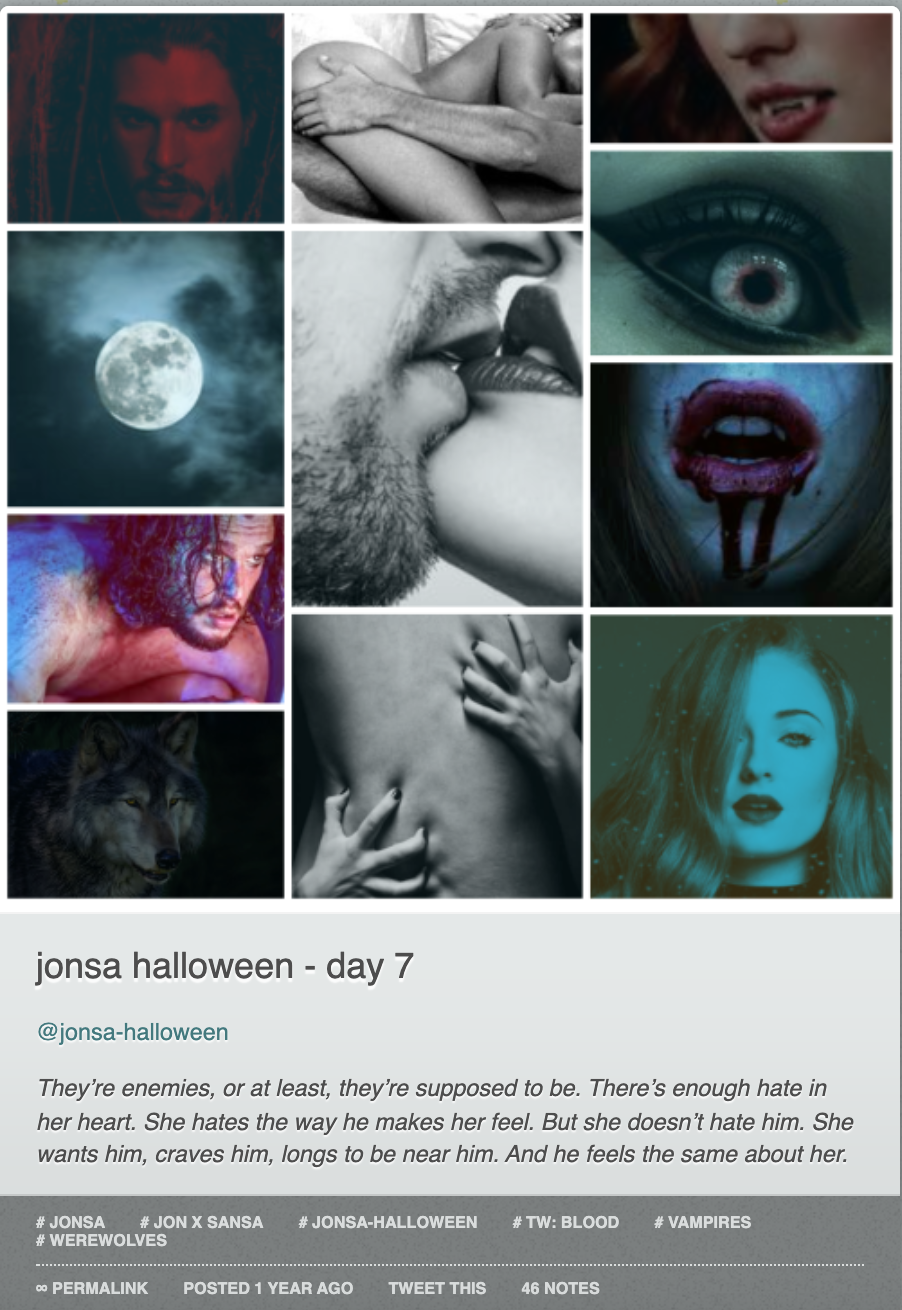

[1.1] As I scroll through the microblogging platform Tumblr (note 1), I come across a post from user Sanzuh titled "Jonsa Halloween – day 7" (note 2) featuring a collage of eleven images arranged in three columns (figure 1). There are pictures of Kit Harington and Sophie Turner, two actors from the HBO series Game of Thrones (GoT; 2011–2019). They are combined with red- and blue-tinted images of a full moon, a wolf, a blood-covered mouth, and a glowing eye. There are also black and white pictures of lips meeting, a woman's hands clawing a man's bare back, and a woman's naked upper thigh. As we look at this pic set, we construct a story: a werewolf Jon Snow (Harington), a vampire Sansa Stark (Turner), and an illicit affair between mortal enemies.

Figure 1. "Jonsa Halloween – day 7," a pic set by Tumblr user Sanzuh.

[1.2] As part of the visual culture of Tumblr fandom, fans create and post pic sets, moodboards, and aesthetics—collages of still images that generate a sense of atmosphere, character, visual style, or narrative. Louisa Ellen Stein (2016) categorizes these compositions as GIF sets, or "sets of images, sometimes animated, sometimes not, arranged in a grid of sorts to communicate as a whole," which "have evolved primarily on Tumblr, where the interface allows for easy juxtaposition of multiple animated or still GIFs." While they are aesthetically similar, for the purposes of my argument, I have elected to distinguish non-animated pic sets from animated GIF sets because of their different affordances. While fans use sets of animated GIFs to create narratives (note 3), the still images in pic sets afford and make visible different modes of networked story construction. I focus specifically on alternate universe (AU) pic sets, which combine pictures of bodies, faces, objects, and locations to create counternarratives that shift characters to different time periods, settings, genres, and stories. These pic sets demonstrate how fans think with and through images, bodies, stories, communities, and ecologies. Members of the fan collectives that gather on Tumblr understand the conventions of how pic sets are constructed, how they are meant to be received, and how to make sense of the different images in relation to each other. As fans look at pic sets, our cognition is enacted through our interactions with texts, images, and the social and technological environment in which they are embedded.

[1.3] Fan creative works—like pic sets—constitute a mode of thinking and reading that is deeply physical, emotional, and social. Building on scholarship in fan studies and the cognitive humanities that demonstrates how our experiences of texts are embodied, affective, and communal, I argue that fans' creative output is not evidence of thinking, but an act of thinking. Fan works form part of the cognitive system of fandom; when we look at pic sets, we both look at examples of what other fans have thought and are invited to participate in a dynamic exchange, encouraged to think with and through them. Cognition is not something that happens in the disembodied mind of the individual fan, but is an embodied and communal act that emerges from fans' interactions with media texts, technological interfaces, and fan collectives. Research in the cognitive sciences—arguing that our minds are extended, embodied, and distributed—can help us understand how fans generate communities of practice and rehearse strategies for engaging with and responding to texts through the creative works they post.

[1.4] As such, pic sets function as part of the cognitive ecology of fandom, constituting and representing fans' engagement with characters and texts. I draw on research in the cognitive sciences, focusing on conceptual blending theory and theories of embodied and distributed cognition, to consider how we experience and make sense of the images and bodies in pic set narratives: that is, how we blend actors and characters, compress faces and identities, and integrate images into a story. Cognitive scientists Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner (2002) enable us to make sense of this fannish phenomenon as a cognitive one: their work theorizing conceptual integration networks can help us understand how we can look at a set of twelve images and fill in the gaps to turn them into a story. However, we do not analyze, experience, or generate narratives from a position of individual disembodiment. Scholarship in embodied and distributed cognition explains the role of the body in how we understand the faces, expressions, gestures, and characters that we encounter in these collages and how we construct narratives within the cognitive ecology of the fan community. While this cognitive science and philosophy work was not developed to discuss pic sets or other fan works, it does allow us to view these activities in new ways and provides a productive vocabulary to describe the visual, literary, and embodied traces of fans' reception and creation practices; it offers a way to locate thinking in the bodies of fans and their interactions with their textual, technological, and social environments.

[1.5] In this way, my work builds on previous scholarship in visual semiotics and fan studies. While semiotics provides a theory for how we make sense of text, images, and their interactions, my interest is in what cognitive science and philosophy research can tell us about the mental operations that underpin these understandings and make them possible. So, while these different approaches might productively be put in conversation with each other, they address questions of mind and meaning from different perspectives and with different sets of assumptions and investments. In addition, considerable research in fan studies addresses the collaborative nature of fandom (e.g., Jenkins 1992, 2006; Busse 2017; Busse and Hellekson 2006; Busse and Stein 2017; Stein 2015; Booth 2016; Jones 2014; Turk and Johnson 2012). I seek to further this research by drawing on theories of distributed cognition to argue that fans are not merely working together as they develop theories and counternarratives. Rather, I reframe this activity as thinking together, not only collaborating on ideas but extending the mind beyond the bounds of the individual. My work also adds to and diverges from scholarship focusing on the embodied experience of fandom (Kelley 2021; Lamerichs 2018; Swan 2018; Coppa 2006; Kirkpatrick 2015; Larsen and Zubernis 2018) by focusing specifically on the thinking that fans do with and through their bodies. The body is not only the object of fan thought but also part of the cognitive system through which we think.

2. A note on methodology

[2.1] To illustrate the phenomena I discuss, I focus on pic sets created by the Jonsa shipping (note 4) subcommunity, a fan collective that I have been a part of for the past seven years. Jonsa shippers are fans who desire to see Jon Snow and Sansa Stark—from George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire (1996–) series and its HBO adaptation—in a romantic or sexual relationship. Though in the canon of the show Jon and Sansa's relationship is familial, these viewers perceive romantic subtext in their interactions, constructing counternarratives about these characters' desire for each other. Because fans write for an audience of other fans, they work from a presumed basis of shared knowledge (Jenkins 1996, 2006; Pugh 2005; Busse and Stein 2017; among many others). I draw on my experience with and knowledge of the source text and the norms of this fan collective that nonmembers do not have. However, where I discuss specific pic sets, I intend them not merely as an explication of an individual text but also as an example of a phenomenon; my analysis is generalizable to other fandoms and other fan works.

[2.2] In addition, following the work of phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1965), my work focuses on the lived, bodily experience of fandom. When I talk about the fan body, I am not discussing the abstracted body of an anonymous person, but rather am drawing in part from my own bodily experience as a fan. My embodied, emotional, and social experiences necessarily inform my thinking—indeed, they are my thinking. While the intersectional identities of our bodies affect our thinking, because they shape our cultural experiences and environments, the cognitive system that underpins how we make meaning shares "significant similarities in neural, cognitive, and kinesthetic operations" (Blair and Cook 2016, 2). According to cognitive humanists Rhonda Blair and Amy Cook (2016), embodied cognition "does universalize the experience in so far as the biologies of the agents are more similar than they are different" (2). Still, in my account of the body—of my body—I am aware of all the ways in which the white, middle-class, cis-het body is privileged and how this body shapes my experience of the texts I read and the communities through which I think (note 5) . For this reason, while my bodily experiences remain an important part of my engagement as a fan and scholar, I acknowledge that they are far from universal.

3. Bodies, faces, and characters

[3.1] Performance theorist Marvin Carlson (2003) discusses the way in which actors are "ghosted" by their previous roles. He argues that actors are haunted by their past performances so that they will "almost inevitably in a new role evoke the ghost or ghosts of previous roles if they have made any impression whatsoever on the audience, a phenomenon that often colors and indeed may dominate the reception process" (8). In pic sets, fans use the haunted bodies of actors to construct AU stories about the characters those actors play. At times, fans also extend the character beyond the boundaries of the individual actor's body so that the character doesn't just ghost that body but—to use another horror term—"possesses" others. Through pic sets, fan communities demonstrate their strength over the source material, using, straining, and overburdening faces and bodies to construct counternarratives about the characters that reflect the communal desires of the fan collective.

[3.2] Central to my argument here is conceptual blending theory (CBT), as posited by Fauconnier and Turner (2002), who theorize the "highly imaginative," often "invisible, unconscious" activity that goes into meaning making (18). This process, referred to as conceptual blending or conceptual integration, is how we project, combine, and network different "small conceptual packets," referred to as "mental spaces," integrating them to create a "blended space" from which new words, concepts, and understandings emerge (40). These blended spaces, Fauconnier and Turner theorize, are created by establishing matches between the input mental spaces and selectively projecting them into a new, emergent space. Through this process, we compress time, cause and effect, and identity, making these concepts more mentally manageable. Compression is a powerful cognitive tool because "we compress what is complicated and diffuse into what is focused and essential in order to decrease the cognitive load, increase associations, and facilitate memory" (Cook 2018, 38); it allows us to think about concepts in different ways, make connections that we might otherwise not, and thus conceptualize an actor as a character, a face as a person, images as a story.

[3.3] We have an extraordinary cognitive ability to blend together the identities of actors and characters, compressing them across numerous mental spaces. When we watch a film, television show, or play, we blend the fictional character and the actual body of the actor, compressing their identities so that the character "sounds and moves like the actor and is where the actor is" (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, 266). This compression extends beyond the performance so that when we see the bodies of actors, we see the characters—the actors' bodies ghosted by the roles they have played even when no longer on the screen or stage. This mental phenomenon, of course, does not mean that were I to see GoT's Kit Harington walking down a New York City street I would think that I was seeing the medieval fantasy character he plays, but in my excitement, I might say, "Oh my god! It's Jon Snow." Or, if I am recounting the plot of Marvel's The Eternals (2021), in which Harington plays Dane Whitman, I might refer to him as "Jon Snow." The integrated network formed by the identities "Jon Snow," "Dane Whitman," and "Kit Harington" is anchored in Harington's body so that these names can be used interchangeably to refer to the same body—no matter which role it is performing at the time.

[3.4] Pic sets play with this compression, using images of actors to communicate the fictional identities of characters. While some pic sets appropriate images of actors from the source text, others do not. Creators integrate images from other films, television shows, and photoshoots into their pic sets, and when we look at them, we understand that in the images, the actor is being the character who ghosts them. In "Jonsa Halloween" (2020), for example, we see images of Sophie Turner from a photoshoot; her loose wavy hair, heavy eyeliner, and dark lipstick are a departure from how the character Sansa Stark is styled on the show. But, though what Barbara Dancygier (2016, 24) refers to as "material tokens of 'characterhood'" are not present, Turner's body is still compressed with Sansa's identity; we still understand her image as the character she plays. As a result, the narrative we construct from the pictures in this set is not that actors Harington and Turner are a werewolf and a vampire caught up in a passionate sexual relationship, but that the characters Jon and Sansa are.

[3.5] The blend of actor and character is not the only mental compression at work when we look at a pic set: they also take advantage of the mental operations through which we compress a person's entire identity down to their face (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, 97). Amy Cook (2018) discusses how the face functions as an anchor for identity, "a compression of the person to a part" (57). That is the reason why I point to a headshot of Turner and say "that's Sophie Turner," not "that's Sophie Turner's face" (Fauconnier and Turner 2002, 97). This synecdochic, "Part-Whole" relationship, Fauconnier and Turner (2002) explain, occurs because "we have constructed a network mapping the individual to the picture of what seems to us her most salient part, her face. In the blend, the face is projected from one input and the whole person is projected from the other. In the blend, the face and person are fused" (97). This phenomenon works for characters as well so that when we look at a pic set, Turner's face is "fused" with and evokes Sansa and the network of identity associations that the character entails.

[3.6] Although, as Fauconnier and Turner (2002) note, there are some "specialized circumstances" where we might compress identity with other body parts—like fingerprints or X-rays—arms, legs, torsos, hands, hair, and feet do not usually anchor identity in the same way that faces do (97). We are far less likely to have a mental space in which we have compressed an identity by "fusing" it with a back or a hand. As Cook (2018) explains, "If we found a photograph of a leg or an arm we would not say 'who is that?'; we might say, 'whose arm is that?'" (57). Even if we recognize parts of a person's body because of their shape or markings, we still conceptualize it as belonging to a person, not as a person. In pic sets, fans rely on this cognitive phenomenon to construct counternarratives. Unlike fic writers, who are limited only by their imaginations, the visual images that are incorporated into pic sets are limited by the available extant material of characters and actors. Fans creatively respond to these limitations by playing with, straining, and overextending the bodies of characters in the service of the counternarratives the community desires.

[3.7] If, as Carlson (2003) theorizes, the bodies of actors are haunted by the characters they play, in pic sets, we see characters extending themselves by possessing a network of bodies. Though fans may be well aware that the pictures of arms, torsos, and hands are not of the actor, those body parts become a part of the character—the body of the actor is overridden by the community's desire for the counternarratives constructed from pic sets. We integrate the faces of the actors and the images of body parts, blending these inputs with the mental space we have already created for the characters' identities. As Jonsa shippers look at "Jonsa Halloween," we don't care if it's not Turner's leg, Harington's back, or the actors' lips because we mentally compress the pictures and identities. The images become Sansa's leg, Jon's back, their lips: the actual body is less important than the story we tell through these images and the community it is in service to.

[3.8] Through compression, we can also incorporate parts of faces that are not but are close enough to the actor into our understanding of the character. For example, "She-Wolf," a pic set by Tumblr user Yesterdayqueens (figure 2), crafts a Jonsa fairytale AU through a series of sixteen images, combining pictures of Jon, Sansa, GoT antagonist Petyr Baelish, wolves, castles, and falling snow. Though the character Sansa is in five of the images in this set, Turner appears only twice. The other three pictures are of other bodies, but when we look at the pic set, we understand them as the character. In one image, we see the lower half of a face, the eyes cropped out, framed by windblown red hair. Even though it is a different face than we are used to seeing on the show, the hair is similar enough to Sansa's that we understand that body as that character. In another picture, a woman's auburn hair is pulled up to reveal her bare back. She is in an intimate position with a man, with the features of both faces in shadow—only their outline visible—and we cast Sansa and Jon into these bodies, into this sensual moment. The third image features a woman with long, straight red hair, looking down, a wolf pelt draped around her shoulders, the beast's snarling head sitting atop her own. The woman's face is in three-quarters profile, and she is clearly not Turner. But she is visually close enough that we are able to project Sansa's identity onto this body and understand this face as that character. When we look at this pic set, we do not see four different bodies, four different characters, or four different Sansas. Rather, because of their similarities—notably their red hair—we integrate identity across these partial faces, understanding them as one character. The actor's body becomes less important than fans' desires for communal counternarratives, a desire so strong that we conceptualize a unified understanding of the character's identity despite the numerous bodies representing her.

Figure 2. "She-Wolf," a pic set by Tumblr user Yesterdayqueens.

4. Embodied understanding

[4.1] As we look at pic sets, we understand characters through pictures of bodies—the actors' and others. However, their stories cannot be told without our bodies. We do not coldly interpret these images, narratives, and networks from a disembodied position; rather, we experience, understand, and think about the bodies in these pic sets in and through our own. Theorists of embodied cognition like philosophers Shaun Gallagher (2005, 2020) and Giovanna Colombetti (2014) as well as literary critics like Ellen Spolsky (1996) and Guillemette Bolens (2012) help us understand how we use our bodies to make meaning of the bodies in these pic sets, how we know what bodies are doing, and what story they are telling.

[4.2] The term "embodied cognition" refers to a constellation of theories united by a rejection of Cartesian dualism. Instead of presenting the mind as distinct from and operating independent of the body, theories of embodied cognition argue that the body is an integral part of our cognitive and conceptual systems. Neuroscientist Francisco J. Varela, philosopher Evan Thompson, and psychologist Eleanor Rosch (1991) highlight the connection between cognition and the body, arguing "first, that cognition depends upon the kinds of experience that come from having a body with various sensorimotor capacities, and second, that these individual sensorimotor capacities are themselves embedded in a more encompassing biological, psychological, and cultural context…sensory and motor processes, perception and action, are fundamentally inseparable in lived cognition" (172–73).

[4.3] We not only access the world through our bodies: it is also through our bodies that we make meaning from it. A completely disembodied mind would be unrecognizable as a human mind because the body is an integral part of the cognitive system through which we understand the physical and social world.

[4.4] When we look at another person—whether they are in the room with us or depicted on a canvas or screen—we understand their thoughts, feelings, and emotions through our bodies. Colombetti (2014) argues that in our bodies, we experience the force of another person shaking their head and feel the movement of facial muscles in a smile or grimace. As she asserts, "I do not just see the other's hand and judge that it is tense, rather I experience the tenseness in the other's hand…When I see the other's tense hand, I 'live' the other's tenseness but do not feel 'primordial tenseness' myself" (174–75, emphasis in original). This ability to feel the experience of other bodies by rehearsing it in our own draws from what Spolsky (1996) calls our kinesic intelligence. As she explains, "human kinesic intelligence is our sense of the relationship of parts of the human body to the whole, and of the patterns of bodily tension and relaxation as they are related to movement. Kinesic knowledge is also our sense of the muscular forces that produce bodily movement and of the effect of that movement on other parts of the body and on objects within the environment" (159).

[4.5] Even when bodies are still—captured in photographs or paintings—we experience them through our own. As Bolens (2012) argues, "art activates kinesic intelligence" (3); when we look at pic sets, we feel whether the bodies in them are relaxed or tense, and we understand their pose, posture, gestures, and facial configurations through our bodies.

[4.6] Our bodily interaction with the world and the other bodies who inhabit it is what cognitive philosophers refer to as "smart." Gallagher (2020) argues that "direct social perception, without any extra-perceptual processes involved, can grasp more than just surface behavior—or to put it precisely, it can grasp behavior as meaningful" (132). When we look at a television still of a character, we do not observe the tension of his lower eyelid, the slight creasing of his brow, the parting of his lips, the relaxation of his cheek muscles, and then draw an inference that he is in love. Rather, we perceive, and feel, his romantic desire directly; our understanding of the character's love and desire does not require that we consciously parse or interpret what his body is doing because we already have a contextual and bodily understanding of it. As we perceive, move through, and interact with the world, the body is already making meaning of it without requiring conscious theorization or analysis.

[4.7] This direct, embodied understanding plays an important role in the narrative and meaning that we generate from pic sets. For example, in a pic set by illmakethemloveme titled "A political union, in writing" (figure 3), we construct an understanding of a canon divergent romance developing from a Jonsa arranged marriage AU. In the first picture of the second row, for example, we sense into the hand in the image, experiencing the delicate way in which it is holding the laces of the corset. We understand the lightness, the gentleness, with which the string is being pulled; we can almost feel the slowness, the nervousness, the tension in the movement. As we compress Jon and Sansa with the man and woman in this image, our embodied understanding of it encourages us to develop its narrative context: Jon and Sansa's gentle, uncertain first coupling (note 6) .

Figure 3. "A political union, in writing," a pic set by Tumblr user illmakethemloveme.

[4.8] We are invited to contrast this picture with the feel of the bodies in the second and third images on the middle line, integrating them into a narrative. In the middle image, we feel the way in which the man's fingers are splayed across the woman's back, the gentleness with which he cradles her body. In the last picture in that row, we feel the passion with which he clasps her to him and her desire as she wraps her arms around his neck and pulls him closer. Through compression, we understand these bodies as Jon and Sansa's, and we experience this intimacy and desire as theirs, representing their developing sexual and romantic relation. The images in the final line of this pic set represent the culmination of this relationship. In the middle picture, we see a man's hand resting on a woman's arm. As we look into this image, we sense into the hand and we live through the lightness of the caress. We feel the gentleness, the comfort, and the love in the way that his fingers touch her arm. Our understanding of the bodies in this pic set, then, does not just rely on compression of identity but also on our own embodied knowledge of how a hand resting in that way feels. As we look at the pic set, there is pleasure in living through and constructing a narrative from the bodies in the images. This enjoyment is communal, as members of the fan collective experience the shared pleasures of this embodied understanding and the fulfillment of the counternarratives they collectively desire.

5. Distributed cognition, cognitive ecologies, and affordances

[5.1] When we come across pic sets on Tumblr, we do so within specific social and textual ecologies constructed through the nested and overlapping cultural environments that shape fan communities. Tisha Turk and Joshua Johnson (2012) discuss fandom through the lens of the "ecology metaphor," arguing that we should conceptualize fan collectives "as a system (or series of systems) within which all fans participate in various ways" (¶ 2.3). This view of fandom can productively be put into conversation with work by theorists of distributed cognition, who defend that our minds are extended by, embedded in, and enacted through our social and physical environments. As we create and look at pic sets, I argue, we don't just think about them, but think through and with them and the ecology in which they are embedded.

[5.2] As many fan studies scholars note, fans do not read or compose in isolation, but in the specific fan collectives that form through fan practices of reception and creation. Henry Jenkins (2006), for example, adopts Pierre Levy's (1994) theory of collective intelligence to make sense of the networks of knowledge that form through and bind together fan communities. Jenkins (2006) describes that "what holds a collective intelligence together is not the possession of knowledge, which is relatively static, but the social process of acquiring knowledge, which is dynamic and participatory, continually testing and reaffirming the group's social ties" (54). Line Nybro Petersen (2014) applies this idea specifically to Tumblr posts, highlighting that notes indicating the level of community interaction demonstrate "if a particular post is popular and part of the fandom's collective intelligence" and "aid in the reciprocal exchange of knowledge in the fandom" (98, emphasis in original). I extend this idea by reframing what fans are doing not in terms of knowledge but cognition: the culturally embedded and embodied process of meaning making enacted through interactions with fan works, the source text, technological interfaces, communal genres, practices and expectations, and each other (note 7). It is not just that fans acquire and share knowledge as a collective, but that they develop modes of thinking, or their cognition distributed across texts and communities.

[5.3] Instead of understanding fans' minds as locked away within individual brains and bodies, I argue that thinking is dispersed throughout and entangled with the cultures they construct and the communities they form. Cognitive philosophers Andy Clark and David J. Chalmers (1998) tell us that understanding the mind requires us to move beyond "the boundaries of skin and skull" to consider how our environments function as part of our cognitive system (7). These environments can be social as well as physical; as neuroscientist Merlin Donald (2006) outlines, "Human cultures can be regarded as massive distributed cognitive networks, involving the linking of many minds" (4). Fandom is one of these cultures, with cognition distributed through fans, technologies, texts, and social structures; thought and creativity are enacted through the interaction of these networks. In this way, fan communities function as what cognitive humanist Evelyn Tribble and cognitive scientist John Sutton (2011) refer to as "cognitive ecologies" (94). As they explain, "Cognitive ecologies are the multidimensional contexts in which we remember, feel, think, sense, communicate, imagine, and act, often collaboratively, on the fly, and in rich ongoing interaction with our environments" (94). Fans' cognition is embodied, dynamic, and extended into the world, emerging through physical and social interactions. Rather than see pic sets as artifacts or evidence of fans' cognitive and interpretative practices, I argue that they are thinking shaped by the community in which they are created and shared. Through exchanges with other fans, communal practices, and technical interfaces, fans extend their cognition and enact new modes of thinking.

[5.4] As a social media platform, Tumblr provides an environment with specific technological affordances with and through which fans think. The term "affordance," as used by ecological psychologist James J. Gibson (1983, 2014) and cognitive scientist Anthony Chemero (2003), refers to the way that we make sense and use of our environment. Affordances are perceived through—and emerge from—the interaction of the organism, environment, and situation and the cognitive system they form. Petersen (2014) argues that "Tumblr is organized in a certain way and operates by a particular grammar, and this enforces a particular manner of communication…affordances are both the possibilities and constraints that structure conversation" (90). As numerous scholars observe, the visual orientation of Tumblr's design explains users' preference for images and animated GIFs over textual communication (Stein 2016; Hillman, Procyk, and Neustaedter 2014; DeSouza 2013; Bourlai and Herring 2014; Perez 2013; Petersen 2014). However, this affordance not only structures modes of communication, but ways of thinking: on Tumblr, cognition is shaped by and extended through the images fans post. The platform's design and functionality make it relatively easy for fans to create pic or GIF sets (Stein 2016), which also introduces new ways of thinking and new understandings of characters and narratives. Pic sets are an affordance of the platform's design, a way to think about and with pictures, characters, and narratives that emerge through fans' interactions with the technological and social ecology of Tumblr fandom.

[5.5] The ease with which fans understand pic sets, that is, compress a collection of images into a shared fictional world and narrative, demonstrates how thinking is distributed across technological, social, and textual environments within the fan community: all environments generated by the individual pic set posts—featuring captions and images—as well as the broader fan collective and culture of fandom. For example, when posted to Tumblr, pic sets are often accompanied by a caption, and sometimes they appear with a longer description or a link to the fan fiction they were inspired by. These titles, captions, and intertextual links provide part of the context for pic sets; the text that is paired with a pic set is integrated into the network of meaning that we form through it. In a discussion of GIF sets, Kayley Thomas (2013), drawing on Roland Barthes's (1977) theorization of text and image, notes that Tumblr's multimodality affords the frequent interaction of visuals and words so that text directs our understanding of image, or they "work in tandem" to create meaning (¶ 3.3). This relationship is perhaps most clear in GIF sets and reaction GIFs where words are superimposed over visuals. However, when it comes to pic sets, Tumblr's design complicates the temporal relationship between text and image. While pic sets often have titles and captions, the platform's scrolling interface places them at the bottom of the post. This positioning means that fans interact with the complete set of images before the text, compressing them into a shared fictional space and constructing a narrative from them in advance of reading the caption. The text might encourage viewers to reassess and revise the story they constructed from the pic set, but their initial understanding is shaped by their familiarity with the medium and the process of making meaning from it, the faces and bodies included in the set, the larger cognitive environment in which it is being received.

[5.6] Our cognitive interaction with specific bodies in the social context of particular fandoms also imbues them with a meaning that they might not have otherwise had. Our understanding of the bodies in pic sets is ecological; we perceive their meaning in relation to each other. Cook (2018) explains that when we watch a play or a film, rather than understand actors individually, all of their bodies and histories are integrated into a network of meaning that informs our understanding of characters, relationships, and stories. A similar cognitive phenomenon occurs when we look at pic sets: we do not make sense of the bodies in them in isolation any more than we would if we were watching a film or play. Instead, we compress the bodies into a shared fictional space and understand their identities in terms of each other. Different characters and narratives emerge from the visual ecology of each pic set. As Barthes (1977) might say, the denotation of the image is the same, but the connotation is not; it is the same body, but it means something different because it is compressed with a different character's identity. However, whereas Barthes separates what he categorizes as "'perceptive' connotation" and "'cognitive' connotation" (29), I argue that perception is cognition. It is not, as Barthes describes, that we perceive the image and then use "our knowledge of the world" to parse and interpret signifiers (29). Rather, our perception is smart; we do not need to individually process them to understand the images. When we look at pic sets, we perceive actors' bodies differently depending on the context in which we encounter them. Technology, text, image, and community—fan cognition about pic sets is distributed across the networks that these contexts create; we think with and through these contexts as they shape our perceptions of the bodies we encounter, the characters we compress them with, the ghosts that haunt them, and the shared fictional spaces and narratives we construct for them.

6. Thinking through stories

[6.1] Membership in a fan collective does not just teach fans how to construct narratives through pic sets but also how to think with and through those stories. AU pic sets, for example, integrate familiar characters into new genres, storyworlds, and roles, requiring us to think about them in new ways. As we look at Jonsa pic sets, we cast Jon and Sansa into the Old West and a Regency-era estate, as a werewolf and vampire, 1940s gangster and starlet, mermaid and fisherman, co-workers at a bakery. In these stories, we see "the recycling of specific characters" (Carlson 2003, 17), with our pleasure emerging from this repetition and familiarity. There is an enjoyment for fans not only in the recycling of characters but also in the nuances, the differences that emerge from casting iterations of them into different visual narratives.

[6.2] Generally, when we talk about casting, we think of assigning an actor a part in a film, television show, or play. However, Cook (2018) argues that casting is a strategy that we also use to create and categorize characters, a cognitive tool for understanding them. In AU pic sets, by casting Jon or Sansa into different roles, Jonsa shippers are making a statement about how we understand their characters and relationship. But casting is not just descriptive but also generative; as Cook (2018) explains, "A casting director may match the perceived qualities of an actor with the perceived qualities of the character, but the combination is also synergistic; casting a character creates qualities" (2). Casting Jon as a Regency-era captain or a werewolf is not just an act of matching the perceived qualities of Jon with the perceived qualities of the role: it is performative in that a new version of the character emerges from this act. Casting characters into different roles in different historical eras says something about the characters, as well as does something to the way that the community understands them.

[6.3] We can discern this process perhaps most clearly in pic sets that insert characters into existing narratives, distributing our thinking about characters through the broader cultural and literary environment. I (Hautsch 2018) have previously written about how we can think of fusion fan fiction—narratives that retell an existing story with characters from different, unrelated texts—in terms of what Peter Khost (2018) calls a "literary affordance," and those principles are also at work in pic sets. Khost applies the idea of environmental affordances to literature and culture, arguing that we make rhetorical use of literary texts. Like their counterparts in the physical world, literary affordances emerge through the organism's interaction with and use of their textual and cultural environments. As Khost explains, "Whereas an interpretation is a textual response that is about the text, a literary affordance is a response to something else through a text" (2, emphasis in original). Examining AU pic sets through the lens of literary affordance helps us see the ways in which cognition about texts is distributed throughout the social, textual, and cultural environment in which fans engage with the source text. Through these sets, we think about characters with and through other texts, creating an intertextual network of meaning.

[6.4] Literary affordance is an inherently and explicitly intertextual practice—and so are fans' creative works, like pic sets. Barthes (1977) argues that texts are "a multidimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash" (146). Julia Kristeva (1980) makes a similar assertion, describing texts as "a mosaic of quotations" and telling that "any text is the absorption and transformation of another" (66). In fan works, texts are merged together, interacting with each other to create different meanings. In pic sets, for example, images from various sources are brought together to create a new narrative while still being indexical to their source. But, I argue, these intertextual referents are also integrated into our cognitive system; they are both the content and the context from which we produce meaning. They are cognitive tools. Through fans' embodied, social, and intertextual engagement with stories, they use texts to not just say something about other texts but also to actively think about them. As we look at pic sets, our cognition is distributed across an (inter)textual ecology so that we are not only thinking about the relationships between stories and characters, but thinking through them to generate new meaning.

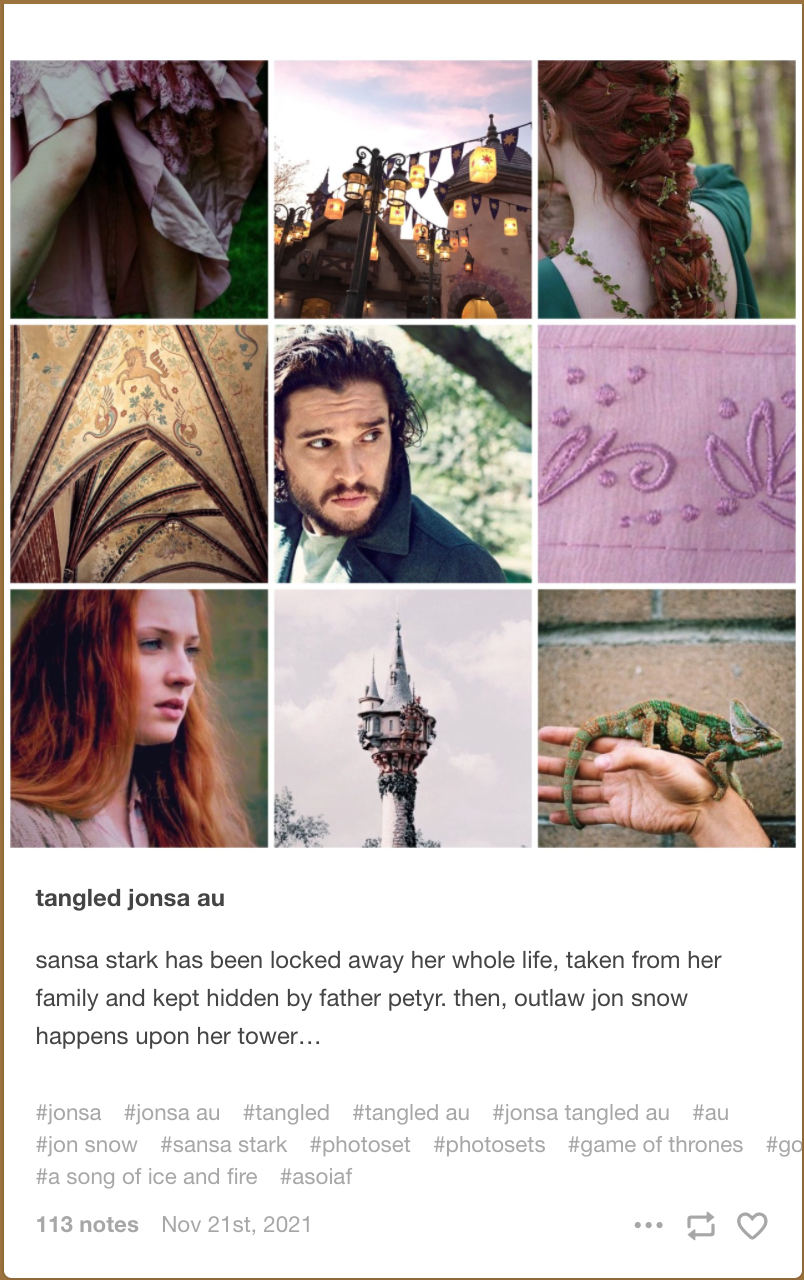

[6.5] CBT helps us understand the cognitive operations at work as we construct links between stories, as well as explains how we can make sense of characters like Jon and Sansa as Grease's (1978) Danny and Sandy (note 8), The Notebook's (2004) Noah and Allie (imagined by otp-that-was-promised), or Tangled's (2010) Rapunzel and Flynn Rider (imagined by ohhaveyouseenme; figure 4). Mark Turner (1996) argues that our ability to understand one story in terms of another—what he refers to as "parable"—is a basic cognitive tool through which we make sense of the world. He explains that in order to understand parables, we build connections between mental spaces, linking them together so that "one story is projected onto another" (5). Through this projection, a blended space emerges—Sansa as Sandy, Sansa as Allie, Sansa as Rapunzel—which then reflects back onto the input texts. As we look at ohhaveyouseenme's "tangled jonsa au" pic set, we make sense of Sansa and Jon in the roles of Rapunzel and Flynn Rider by mapping connections between our conceptualization of these characters, their analogic and disanalogic relationships. For example, we might make sense of Sansa in the role of Rapunzel by drawing connections between their shared trapped princess archetype, their experience of being imprisoned and abused by people posing as parental figures, their love of the arts, and their narrative arc of empowerment. We can link Jon's protectiveness with Flynn's, their deaths and resurrections, and their large white animal companions. It is not just the similarities but also the differences between the characters, though, that are important to how we think about them through this pic set. For example, outlaw Flynn's devil-may-care arrogance and charisma doesn't map with Jon's characteristic honor and brooding. In order to cast Jon into this role, in order to make sense of him as this character, we generate a new version of Jon and a new version of Flynn, and a new way of thinking about them both.

Figure 4. "Tangled jonsa au," a pic set by Tumblr user ohhaveyouseenme.

[6.6] The pleasure in these pic sets is not only in the repetition of characters but also in the exploration of their relationships that emerge from casting one character as another. As we cast the characters from GoT into these other narratives, we make sense of who should fill which roles not just by considering the traits of the individual characters but also the ways in which the characters interact and the relationships between them. For example, we might draw connections between the relative social standings of Jon and Sansa and those of the characters in Tangled, making sense of them in terms of their relationship with each other. Jon, believed to be a bastard for most of the series, initially has a lower social status than trueborn Lady Sansa. The class differences between Princess Rapunzel and outlaw Flynn can be mapped onto the unequal births of Jon and Sansa, drawing our focus to that aspect of their relationship.

[6.7] How the community frames the relationship between characters, then, plays an important role in terms of deciding whether or not casting works—as does the communal desire for specific relationships. For fans who ship Jonsa, the Tangled casting makes sense because romance maps input spaces and structures the blend of Sansa and Jon as Rapunzel and Flynn. For fans who don't perceive their romantic viability, slotting Jon and Sansa into the romantic leads of another story is not compelling—or pleasurable. As we cast beloved characters into other narratives, we make sense of who should fill which roles not just by considering the traits and canon of the individual characters but also the desires of the community. Jonsa shippers want to see narratives in which Jon and Sansa are romantically involved with one another. No matter what stories or worlds these characters are thrown into, the communal desire for them to fall in love structures the creation and reception of narrative pic sets. They invite new ways of thinking about and through characters and a community of fan readers.

7. Conclusion

[7.1] Linguistic anthropologist Shirley Brice Heath (2006) asserts that "mental work must be done to bring separations together into a whole. Seemingly unrelated figures all go about their business within the same two dimensional space. It is the task of the viewer to figure out what holds these entities together other than the physical boundaries of the artwork" (136). She isn't writing specifically about pic sets, but the same principle applies to how fans view and understand these collages. What holds together the images that fans include in their pic sets? What brings them together into a shared fictional space? I have argued that it is the fans themselves, their bodies, and the community—its desires and modes of thinking—in which a pic set is constructed and embedded. Fans know what characters they want to see, what stories they want to be told, and the methods of constructing them from a pic set. As we view the images, our minds perform the cognitive operations of filling in the gaps, of bringing together these separate, "unrelated" images to create characters through bodies and construct a narrative through a network of pictures.

[7.2] Rather than view fan works like pic sets as artifacts or evidence of fans' cognitive and interpretative practices, I argue that they are fan thinking, shaped by the community in which they are created and shared. Fans' reading and creating strategies are not just about understanding the text, but cohering a collective, generating a community. We read toward a networked collective of other fans, other readers. Membership in this community shapes our thinking as readers and creators, how we respond to texts, and what we do in response. Our cognition about texts is smart in the way that Gallagher (2020) uses the term because it is enacted through an adaptive network of texts, practices, and readers. By adopting a social and embodied orientation toward the text and the collective, fans align themselves with a large and distributed network of readers who have adopted a similar position. Our understanding of source texts and fan works does not emerge from only the text or our individual brains or bodies but is also distributed across and enacted through our interactions with other texts and fans. The reception and creation practices of fan communities are part of the cognitive ecology in which fans think and feel, read and write. As we look at pic sets, our understanding and pleasure of them emerges from and is distributed across bodily, intertextual, and intracommunal cognitive interactions.