1. Introduction: Fan binding and book history

[1.1] Fan fiction corresponds to several prominent topics in book history, including copyright and publishing history, reader-author relationships, communal reading practices, and material production. I understand the increasingly popular phenomenon of bookbinding fan fiction (fan binding) as an aesthetic-craft practice that follows in the footsteps of twentieth-century zines, which Catherine Coker (2017) recognizes as one entry point to fan fiction as book history. She notes that early fanzines were defined in opposition to professional zines (prozines) and comprised "amateur writing by self-identified fans rather than the transformative works" of contemporary fandom. Many fan binders share this ethos of self-driven fan object-making apart from traditional publishing outfits, and they progress a gift economy through gifting fanbound works to fic authors, just as zine makers often circulated fanzines for free or in exchange for comparable works. Coker notes that fanzines were often collaborative projects through solicited submissions that were compiled during collating parties, or gatherings of zine contributors to staple printed pages and stuff envelopes. Renegade Bindery, a community of fan binders hosted on Discord, similarly locates fan binding to a collaborative exchange space: Though a fan binder may individually procure and assemble binding materials, they exchange techniques, suggestions, resources, and encouragement in the server. I understand fanzines and fan binding as sharing a comparable community ethos expressed in the coterie craft of print-object making.

[1.2] With these aesthetic, collaborative, and gift-economy features, fan binding challenges commonly held book historical models of book production, such as Robert Darnton's (1982) communication circuit. Here I examine how bookbinding as a fannish response progresses the fan fiction communication circuit—an extension of Darnton's circuit that accounts for the reciprocal gift economy of fan fiction production—and discusses how this practice construes value for printed works through affective labor rather than commercial return.

[1.3] Like fic writing, fan binding is mostly an amateur endeavor in that its practitioners craft for love, not financial compensation. All of the binders I interviewed, save for one with a masters in book arts, are self-taught. A few began fan binding by placing printed copies of fic in three-ring binders or printing at a copy shop; others took a class and pursued their interest through online resources. Some fan binders have been binding for a few years; many took advantage of their increased free time during the Covid-19 pandemic.

[1.4] Despite Coker's (2017) efforts to bridge the fields, fic has been understudied by book historians because it is digital, noncommercial, and nonprofit. For fan binders, making physical art objects counters obsolescence and data loss and provides a break from the screen, traversing a porous boundary between digital and physical fandom and a similar one between digital and material texts. Fan binders exemplify Leah Price's (2019) refutation of the "death of reading" narrative and Jessica Pressman's (2020) examination of aestheticizing attitudes surrounding books, materializing their binding practice during a prolonged digital-age lamentation of the loss of "tangible" reading materials. Their work exhibits that fic, fandom, and bookmaking are not confined to a single medium, following fandom's tendency to adopt new digital means of creation and exchange while retaining material object-making practices (Versaphile 2011).

[1.5] Fan binders create homemade books that additionally complicate book production models reliant on the "follow the money" principle, providing a case study for book historians to reevaluate our descriptive models. By practicing this private affective labor, bookbinders construe value for fic with their personal investment in the work (both the fic itself and the process of binding) and their intent to return gifts to the fic writer (Coker 2017). They connote book production as not-for-profit and privately consumed. The binders I interviewed strongly rejected commercialization of fic, and most were hesitant to solicit binding commissions for a variety of reasons, ranging from expertise to unapproachable costs. The formal and subversive constraints of fan fiction separate it from the traditional for-profit publishing communication circuit and traditional modes of text distribution. Bound fic, rather than aligning the text with book publishing simply because of its codex form, further distances fic from that traditional circuit as it assigns the codex with new production and value meanings.

2. Reviewing Darnton's communication circuit

[2.1] Robert Darnton's (1982) communication circuit describes the circulation of a text through different actors, influenced by various socioeconomic and political factors, to produce a book (figure 1). His model is sufficient and adaptable for describing the relationship between author, printer, publisher, distributor, and reader in his communication circuit. But three key characteristics of fan fiction, as defined by Francesca Coppa (2017), place fic production adjacent to Darnton's circuit, challenge for-profit motives of textual production, and attend to the reciprocal nature of fan fiction communications. First, fic is "created outside of the literary marketplace" (2). Second, fic "rewrites and transforms other stories currently owned by others" (4). Finally, fic is "made for free, but not 'for nothing'" (14). Although fic is rarely made for profit, writers often receive likes, reviews, art, and friendship. This gift-based economy of giving, receiving, and reciprocating underwrites fandom and is crucial to the circulation of fannish response to fic writers.

Figure 1. An abbreviated model of Darnton's (1982) communication circuit does not account for the social, political, and intellectual influences that contribute to book production.

[2.2] Because fan fiction exists alongside its source text—and by extension the literary marketplace—I model the fan fiction communication circuit in tandem with, rather than superimposed on, Darnton's circuit (figure 2). The reader progresses the circulation of text between the two circuits. For example, the reader's desire to spend more time in a source text universe like The Lord of the Rings, encountered in the right-hand circuit through traditional means like a publishing house and a bookstore, drives the search for fic text and creative fan products, circulated in the left-hand circuit through fandom means, such as sites like Archive of Our Own (AO3) and Tumblr.

Figure 2. Placing the fan fiction communication circuit (left) next to Darnton's (1982) model (right; figure 1) shows the affordances fandom adds to a text's circulation.

[2.3] Binding fan fiction is just one kind of fannish response to fic, among comments, shares, fan art, and more fan fiction. Fan binding challenges the digital reliance of fan fiction and counters the narrative of book production as a for-profit, publicly circulated enterprise. Produced for personal use, at personal cost, and often as a gift for the fic author, bound fic completes the fan fiction communication circuit, reciprocating author labor with gifts rather than remuneration. Fan binding suggests a volume's worth relies not on public recognition but on personal meaning.

[2.4] Analysis of bookbinders' motivations, along with study of how their fannish work fits into the fan fiction communication circuit and how this work upends commercially focused notions of book production, taken together, reveal the challenges of digital-to-material preservation: the printed form of the fic contains different information and provides a different reading experience than the digital form. In the fan fiction communication circuit, fan binding is a creative fannish response with aesthetic and craft elements, as many binders design the books in relation to their content. Binders often circulate a copy back to the writer, perpetuating fandom's gift-giving economy and community function. This reciprocation reinforces the "fannish response" node (figure 2) between reader response and writer function, completing the fan fiction communication circuit.

[2.5] This circuit, however, does not account for the practice known as filing the serial numbers off, or repurposing a piece of fan fiction for a general audience. This practice places the text into the traditional publishing circuit with the purpose of for-profit distribution. I distinguish pulled-to-publish or filed works from fan binding on the basis of production modality: fan binding is a hands-on technique that produces bespoke book objects, whereas filed works might shift that production to a third party, likely for large-scale production. I additionally distinguish between the two on the basis of commercial return: fan binders might make small commissions on individual projects, but they do not systematize profit in the way traditionally published or even self-published works do (note 1). For this article, I distinguish fan-bound objects as separate from and exchanged outside of the traditional publishing circuit. Instead of gaining affirmation through institutionalized gatekeeping entities like literary agents, publishing firms, and bookstores, fan binders affirm the texts through private practices and gifted circulation.

[2.6] As an aesthetic and artistic craft practice, fan binding lies at an intersection of textual production and object making characteristic of fan works. It aligns with other modes of material and digital object making, including fanzines, podcasts and podfics, vids, fan art, and cosplaying. Fan binders' commentary on cost and time management or reflecting the text through aesthetic choices might resonate with cosplayers or fan artists who similarly make aesthetic choices attuned to both personal preference and their fandom's universe. Fan binding tends to the book as both a textual and artistic object, linking fic text and art making. This fan fiction communication circuit begins by accounting for the production, consumption, and circulation of the fic text, to which fan binding is one form of fannish response. From a book historical perspective, fan binding also operates as an organic outgrowth of writing a text and placing it into a recognizable codex form. Although fan binding subverts that recognition, it cannot account for all fan object production. The fan fiction communication circuit may also be usefully amended and elaborated to consider other modes of fannish response to fic text, such as fan art, fanzines, or other fan objects, or else reorient the model to center the artist, listener, or viewer instead of the reader, whose entry points into the circuit may not hinge on fan fiction but on other fan works and fannish response.

3. Methodology

[3.1] The primary evidence I used for this study was interviews conducted with thirteen bookbinders and members of Renegade Bindery, a server hosted on the chat communication app Discord. I chose to conduct the interviews within the preexisting community of Renegade Bindery, where members share resources, techniques, and their completed projects, rather than ask participants to regroup on another platform. I coordinated with the founder of the server, ArmoredSuperHeavy, to introduce my dissertation topic and the opportunity to participate in interviews. This study underwent a research ethics review and implemented adequate safeguards in relation to issues posed by consent, confidentiality, and data management, as required by the School of Advanced Study's research ethics protocol. Participants had to opt in. All participants were of legal age, read an information sheet about the project, and signed a consent form before being given access to a locked channel on the server. At the time of these interviews (via Discord from July 15 to July 30, 2020), the thirteen interviewees were a quarter of the total membership, providing insight into a significant portion of the Bindery's practices; as of June 2021, membership has grown to nearly 375 people. The practice and community have coalesced so rapidly that at the time of interviewing, participants referred to this practice with a variety of terms, including "bookbinding fic" and "fic binding." As of May 2021, the practice is more generally referred to as "fan binding" to be inclusive of binding a variety of fan works, not just fan fiction.

[3.2] I posted thirty-three questions in the locked channel over the course of two weeks in July 2020. The questions are provided in this article's online appendix. Eight interviewees responded directly in the thread to aggregate and reference one another's responses. I followed up via private chat with five participants who preferred to answer the questions via Word document, and in one case, in an audio-only interview conducted over Discord. All responses were recorded in a password-protected server on an encrypted device and have not been repurposed for additional research.

[3.3] In line with fan studies methodology, all participants reviewed drafts of this article so they could clarify the meaning of their statements. They also all received a copy of my final thesis, from which this article is adapted. I refer to the binders anonymously to respect their privacy. Citations are prefixed P- and Q-, which corresponds to the assigned participant number and the number of the question they were responding to.

4. Motivation: Bookbinding as fannish response

[4.1] Bookbinders bind fic for many reasons: they want a print object to reduce screen time and to carry around; they want to gift book objects to fic writers; they enjoy the challenge and craft of putting a book together. Binders love the fics they bind. One binder wrote that her major motivation is her "love of some fics that I read repeatedly (too late at night when I should be sleeping and I can't set my phone down)…I do miss having something physical to hold" (P4, Q13). Another binder wrote, "I really like the idea that I can give fics to the author to help them know that others enjoy their fic and hopefully really cement their love of sharing that fic with others" (P12, Q13). Most of the binders thought that bookbinding allowed them to reciprocate a gift to the writer who gave them their favorite fic, and that doing so encourages writers to continue sharing their work, thus completing a communication circuit (P6, Q1; P4, Q21) (figure 2). Intentional fic preservation is an additional benefit rather than the primary motivation of fan binding for most binders, although one binder noted it as the primary motivation.

[4.2] Hard copies of fic are appealing for reasons such as beauty, a sense of accomplishment, and the challenge of bookmaking. One binder wrote, "It's quite fun to hold something both beautiful and entertaining" (P3, Q32). Another concurred: "The appeal lies mainly in the process of making the book, honestly" (P10, Q32). A third added, "It's about the Fwoomp [sound] when you put it down. No, in all seriousness: I like my hard copies because I like making them, more than I like having them. I like the challenge, I like learning about formatting and design while I do it" (P5, Q32). The satisfaction of making a book is as appealing as having the object itself, and practicing a self-taught craft in leisure time aligns with the nonprofessional precedent of fandom.

[4.3] Fan binding is also a form of reader response. Ten of the binders read the fics before they bind them; only two bind fics on the basis of recommendations from trusted friends or before they finish reading texts themselves (P1 and P8, Q3). All of the binders select fics to bind on the basis of which works they keep returning to and whether it will bring them joy to hold those works in their hands (P6 and P8, Q4). Three deliberately bind fics about queer characters, and one prioritizes fics that feature queer kink, transgender identity, or established tropes such as enemies to lovers (P1, P3, and P4, Q4). Two expressed concern over selecting fics that can "stand on their own in a few years" when memory of canon has faded, suggesting that unlike during the initial reading, prolonged enjoyment of a fic relies less on intertextuality with the source text (P5 and P3, Q4). Six binders also consider the fic's length to ensure it is an appropriate size for a book, sometimes combining shorter stories into an anthology to give the book a proper heft (P3, P4, P7, P8, P11, and P13, Q4).

[4.4] In preparing the text, binders spend considerable time typesetting, cleaning up the remnants of HTML, and selecting typefaces and ornaments to complement the fic. Each binder prefers different elements of the process. One noted that the covers and endpapers are the most important to her to communicate the book's aesthetics (P4, Q14). Another echoed that the binding can reflect the contents of the book: "I'm ordering bookcloth in red/yellow/green/blue for a series of Hogwarts fic in which the founders have their own story" to match the color themes of the school's four houses (P7, Q14). A third described this design process as "incorporat[ing] some elements of the visual identity of the universe in which the fic takes place" in the book's construction and presentation, like matching the binding to characters' signature colors (P9, Q14). One binder painstakingly chooses ornaments and typefaces "based on the time period, for historical fiction, or to complement themes in the book" (P1, Q14) (figure 3). Another binder attends to the aesthetic of traditionally published works in the genre; for his Lord of the Rings fic, he cross-referenced four different publishers and learned the "rules of Tolkien's legendarium" to match the book with its the fictional universe (P3, Q14). Incorporating story elements into the visual expression of the fic demonstrate that the binders are not simply creating an aesthetic object but also thinking critically about the work as readers.

Figure 3. One binder selects ornamentation and typefaces that match a fic's era and subject matter. Image: Participant 1, "Firenze" by EatTheBunny and WhiskeyAndSpite, 2020.

5. Reciprocation: Completing the communication circuit

[5.1] While only two of the bookbinders I interviewed began fan binding specifically to give copies to fic writers as gifts, seven more have adopted the practice or plan to send copies of fic once they complete their volumes, and five credited fine-tuning their gift philosophy to connecting with this bookbinding community. Nine of the thirteen binders noted that they have sent or are sending fic to writers, while three others noted that they would like to do so but have not or cannot as a result of logistical or financial constraints. Gifting bound fic to the writer is "the best part of the whole thing" for one bookbinder (P1, Q22). Another echoes this sentiment: "It's very important to show appreciation to the people who make the stories that we're binding at all…The effort of binding an entire book has to be the strongest demonstration of 'I loved your story this much!' there is" (P3, Q22). This binder illustrates that the bookbinders reciprocate the effort of fic writing with the labor-intensive process of constructing a material form for that fic and returning it to the writer. This practice circulates creative products back to the writer, completing the communication circuit. Likewise, positive writer response to these gifts (via mini photo shoots or personalized thank-you notes) demonstrates that fan gifts affirm writers, strengthening the exchange of creative products through the circuit (P6, P1, P5, Q23).

[5.2] Although many binders share fic with their writers, there are mixed approaches to asking writers permission to bind their fics. In general, the binders ask permission, but at different stages and for different reasons. One binder wrote that because production is sporadic—they may spend weeks typesetting and preparing before a text is ready to print—they ask the writer only once the text is about to print or already printed to avoid the pressure of an ensuing deadline (P1, Q21). Another binder lamented that it is sometimes difficult to track down writers, especially those of fics posted a decade ago who may have since left the fandom. She approaches writers by informing them, "I'm going to print this fic. I'd like to thank you by making you a copy as well" (P2, Q21). Seven others ask but will bind a fic without permission and not share the results publicly on Tumblr or other sites. The binders also distinguished between asking permission for personal use versus for sharing: two concurred, "If it's just for me, I fall into 'you posted it on the internet, you wanted people to read it, ultimately what difference does it make if they read it digitally or via hard copy'" (P7 and P13, Q21). Three others thought that "it's important to ask before binding because of the relational aspect of fandom" (P3, Q21; P4 and P13, Q21–21a). They ask out of courtesy and, when offering to share a copy, to acquire a mailing address. The intention to reciprocate the gift, more than obtaining approval, necessitates writer consultation. These varying responses suggest that within the fan fiction communication circuit, fannish response operates independently of writerly agency over their work.

[5.3] In short, bookbinders are motivated to bind fic for a variety of reasons, including reducing screen time, the challenge and craft of book making, a desire to give book objects as gifts, and a desire to affirm the work of fic writers. Their reciprocation of fan-made gifts circulates creative products through the communication circuit, progressing the model of gifting, receiving, and reciprocating that undergirds fandom activity.

6. Complication: Bookbinding fic versus traditional publishing

[6.1] While producing these books is a resource-heavy task, bookbinders challenge the notion that only the worthiest information merits the cost of book production and that only traditional publishing can establish a work's worth (Reinking 2009). One binder has stated on Tumblr and in interviews the intent to bind works that would never be published by traditional publishing houses (Conjoined 2020). Bookbinders undertake this expensive hobby because they enjoy it and it is meaningful to them, attending to the "felt life" of reading over commercial motivation. Their not-for-profit, private practice inverses the publicly circulated, for-profit book production model that dominates the narrative of book publishing. In the literary marketplace, this kind of self-publishing is often devalued because it is for pleasure, without a known locale of production, and is separate from publishing institutions (Coker 2017). The value of a book is tied not only to its circulation and profit but also to who is circulating and profiting from that work (Coker 2017; Cupidsbow 2007). For one binder, fan binding fic into codex form conveys its social and material legitimacy—a legitimacy equal to that of traditionally published works (ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020). Fan binding challenges fan-written texts' marginalization by tying its value to a personal relationship with the text, to the effort expended putting it into a new form, and to sharing it with the writer.

[6.2] That effort is laborious and time-consuming. Each stage of a fan binding project takes various amounts of time, depending on a binder's experience and facility with the materials. Formatting a fic in a desktop publishing program (Word, InDesign, or Affinity Publisher are the three most popular programs) takes anywhere from two to twelve hours, or four hours for a 150- to 200-page work (P1, P6, P8, and P11, Q8). Folding, sewing, gluing, and casing takes three to five hours (figure 4); producing a single book can take anywhere from eight to twenty hours (P1, P2, P6, and P11, Q8). Some binders group tasks, such as cutting down papers or book cloths (figure 5). The amount of time spent per day also varies; some dedicate a few days a week to projects. Most work in three- or four-hour bursts. Besides one binder who prints using Lulu, an on-demand self-publishing service, and one who prints at Staples, all the binders print the works at home. The lack of outsourcing of aspects of production emphasizes the binders' dedication to their craft.

Figure 4. Compressing pages (participant 9, 2020).

Figure 5. Grouping tasks (participant 1, 2020).

[6.3] Bookbinding is an expensive hobby. When asked about the unit cost per volume, the binders lamented their expenses, with one responding, "That's such a painful question. If I figure it out, I might cry" (P2 and P5, Q10). One binder wrote that the material costs of a small, hundred-page book printed using inexpensive papers are about $12.50. In contrast, "for a large 500-page book I make two copies of, use premium text paper for the block and hand-marbled papers on the case, then ship one to Europe, the cost of materials and shipping is $104.00" (P1, Q10). Another binder calculated his labor costs: "If I'm also investing at least $96 of my own time for each individual volume (considering myself a novice and assuming my office's starting salary of $16/hour), then each volume still can be called about $112. Holy shit!" (P3, Q10). One binder wrote that she is "very focused on the cost of supplies" and often recycles materials, like thrifting a leather skirt for covers, waxing her own cotton thread, and using package cardboard for boards, making her biggest cost printing at Staples (P11, Q10). The combined cost with no monetary return signals that these binders bind fics because the works have value as art and objects; they are not meant to earn a profit.

[6.4] Despite these costs, the majority of the binders are disinterested in or uncomfortable with commissions, a hesitance partially related to fandom's gift-giving ethos. Challenging commercialization of books and book making is one of Renegade Bindery founder ArmoredSuperHeavy's primary motivations to fan bind, and their philosophy conceives of fan binding as directly contrary to traditional publishing. Six binders noted that they knew the history of gift giving in fandom or understood it implicitly, and five binders absorbed this knowledge through fandom spaces or via ArmoredSuperHeavy's public posts about their fan-binding philosophy (P1, P3, P5, P6, P9, and P10, Q19; ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020). Two binders additionally noted that they want to preserve the "rare and precious phenomenon" of the fandom gift economy, especially as younger fans seek to capitalize on their work (P13, Q19; P1, Q25). Survey data suggest that older fans are indeed more committed to fan fiction and fandom as amateur enterprises (Klink 2017) (note 2). For four of the binders, bookbinding is the first or an additional way they have participated in fandom gift culture, alongside fic exchanges and fan art (P4, P6, P9, and P10, Q19).

[6.5] But concluding that the binders avoid for-profit production exclusively because of fandom's gift-giving ethos is disingenuous. Accepting and pricing commissions is tricky for a variety of reasons. One binder found that taking commissions "chang[ed] the dynamic between me and the author and the commissioner—they were customers now, I had a deadline" (P1, Q20). Setting a fair wage pushes items' prices to $275 or $350, or even higher (P3, P7, P8, and P11, Q20). The bookbinders are all aware of the value of their labor; they noted that a fair wage would price one of their books well out of reach for an average buyer. Regardless, none of them actively bind fic for the financial incentive; rather, they do it for artistic and altruistic reasons. Three binders noted that they were still beginners and would not feel comfortable selling a project without more experience (P3, P6, and P7, Q20). Four binders wrote that they would accept general binding commissions of only nonfic texts, as they want to avoid profiting from another writer's fic (P4, P5, P8, and P10, Q20). These same binders wrote that they would likely only charge for the cost of materials, leaving out their labor. Only one binder wrote that they would accept commissions—and also noted the high price tag: "A full leather hand-bound [book] would retail for about $600. Most artist books retail around $200–$300. I'd probably ask for similar amounts to the artist books, around $150–$200" (P11, Q20). Hesitation regarding commissions is not due to adherence to fandom's gift-giving ethos (although that is present) but rather due to a confluence of factors of working for pay, fair wages, and not exploiting someone's work. Collectively, the attitudes toward commissions, pursuit of this hobby despite the costs, and valuation of fics alter the meaning of book production from for-profit to affectively driven.

7. Redundancy of preservation

[7.1] Anthony Grafton (2009, 311) notes that to understand books, we must interview them in their environment. Thus, to understand bound fic, book historians must attend to two fannish environments: the unstable digital distributing platforms from which fic came and the material preservation form born in fannish response. The history of fandom media illustrates the instability of digital media in many ways: links break, sites crash, depots decay (Versaphile 2011). Eleven of the binders I interviewed experienced fic loss—usually returning to bookmarked fic only to find it gone—but few said that loss exclusively influences their desire to bind fic.

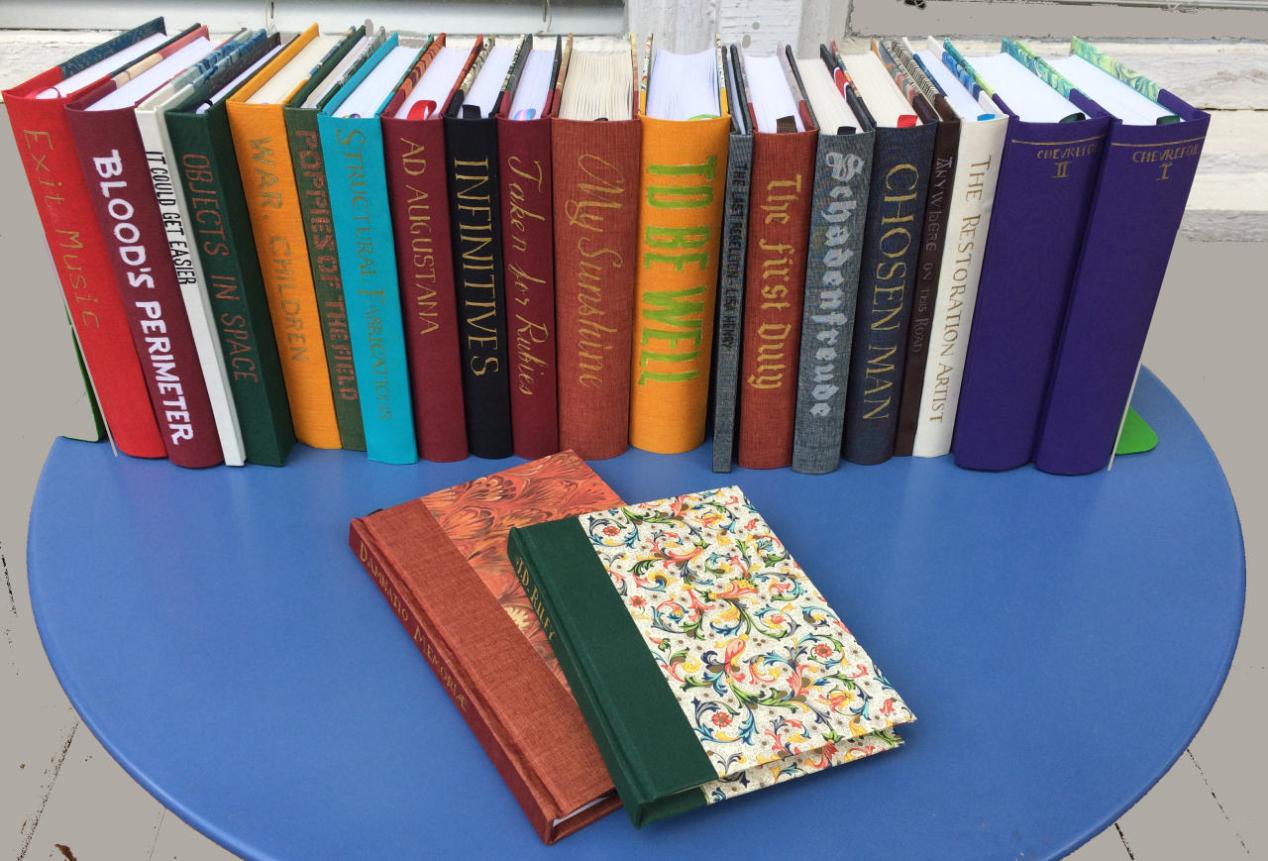

[7.2] When I asked about who or what could be trusted to build a reliable fic archive, the binders unanimously cited the AO3, but with trepidation. One binder wrote, "I do not have unshakeable faith that they will be able to remain successfully funded for the foreseeable future or that laws won't be passed that lead to the site being shut down. The key to survival is redundancy, both digital and offline" (P1, Q30). Another echoed this thought: "The entire internet is ephemeral, and I have had too many technical snafus to put my entire trust into digital format" (P3, Q30). A third noted, "I'm going through my bookmarks and archiving them to the Internet Archive so they are protected against author removal" (P4, Q30). The binders were wary of relying on digital forms, so although preserving fic is not a driving reason to fan bind, it is on the list. Preserving works in print also communicates their legitimacy, especially for queer works, which historically have been condemned or destroyed (P1 and P11, Q13; P13, Q31; P8, Q4) (figure 6).

Figure 6. Personal library (participant 1, 2020).

[7.3] Yet while bound fic counters the pitfalls of digital sites, where fan works may be lost without warning, it lacks real-time feedback, links to additional fan works, and digital metadata that relates fic to the larger community production. This metadata, such as summaries, author notes, disclaimers, and tags, often becomes redundant in print. Thus, during their preservation process, the binders change the text to streamline the reading quality from digital to print form, a trade-off they account for in a variety of ways. All of the binders cut comments, and many exclude or rearrange any combination of summaries, author notes, disclaimers, and kudos and hits statistics according to their personal criteria. They range in their approach to formatting metadata. Two binders include the author, title, tags, archive warnings, and so on in a pseudo copyright page, with content warnings and research notes as appendixes (P1 and P3, Q15). Another lacks sentimentality around these excisions; for her, fan binding "is less of an archive project than a pleasure project," so the concern for preservation gives way to readability (P2, Q15). Conversely, one binder who has bound 104 fics has modified the typesetting process to expedite the time from screen to print in an attempt to bind as many fics as quickly as possible:

[7.4] Nowadays I drop everything in and go, for two reasons. I try to do a lot of fics and [editing author notes] is a huge time suck. But these notes are also significant as part of the metatext. In the future, these will be of interest to any scholar studying early years of online fandom and just contributes to these books being a time capsule of a phenomenon that is very specific to our time and place. (P1, Q15)

[7.5] By favoring production speeds over editing, this binder prioritizes print preservation (and documents a book's environment for a future book historian). Ten binders similarly move metadata and extratextual information to appendices or to smaller side bindings to avoid interrupting reading flow without eliminating the information (P3, P4, P5, and P7, Q15). Although the lack of text editing seemingly counters the attention to craft, the binders distinguished between the craft of the book—its binding, endpapers, and ornamentation—from the content of the text itself. Formatting a text can be the most time-consuming task, so reducing that process expedites the production of a volume.

[7.6] A few themes emerge regarding losses in transforming fic to print form, including accessibility, interactivity, and malleability. Only people with copies of the fic can read those copies, although the fic remains online for the time being. Losing hyperlinks and comments strips the fic of its community context. Printed versions inhibit the writer's ability to edit and update the fic; indeed, one binder noted that fan binding's greatest strength and weakness is that it makes fic "a fossil of a fixed point in time…It leaves no room to adapt" (P13, Q31). But the gain is a hard copy and a sense of enduring preservation independent of online activity: "As long as Modern English can be read and the book remains undamaged by water, fire or other problematic time-passing problems, it is here and real" (P4, Q31). This kind of preservation aligns with a history of recovering lost works via their textual commentaries; were every copy of Harry Potter to be lost and the internet wiped, one could reconstruct the events of the series through bound copies of Annerb's "The Changeling" and dirgewithoutmusic's Boy with a Scar series. Similarly, where the digitally linked community disappears, it is reformed through binders sharing a copy with the writer, who "gets to see how a reader put different materials together to best represent their work" (P6, Q31). One binder wrote, "I think this is a case of having your cake and eating it too: the electronic copy is still there for the wider audience to read, the text is set in a permanent form which has its own artistic value" (P9, Q31). The gains of permanence, the opportunity to create a physical object, and the ability to thank the writer for their work through bound fic outweigh the instantaneous losses of accessibility and digital interactivity.

[7.7] One of my final questions for the binders asked about the long-term preservation of their library: where will their bound works go if they can no longer take care of them or die? One binder was in discussion with the University of Iowa Libraries' Special Collections and Archives (https://www.lib.uiowa.edu/sc/), which is home to a notable fanzine collection and partners with the Fan Culture Preservation Project through OTW's Open Doors to preserve nondigital fan works (P1, Q29). Four binders plan to send the volumes to fandom friends, two want to bequeath their volumes to family members, and two have stated their wishes in their wills (P2, P5, P9, and P13, Q29; P3 and P4, Q29; P3 and P13, Q29). One added that he trusts fans to appreciate fan-printed books as both "stories worth reading" and as art objects, rather than nonfans, who do not understand the connotations of the works (P3, Q30). Fan binding is a momentary win in the long-term battle against information loss, and these personal libraries prolong the question of how and where these works will survive. One binder emphasized the aesthetic, literary, and historical value of these volumes: "I think that people making fine binding versions of fic absolutely validates their place in libraries, and I have no doubt that some of the books made by the fic binding community will make their way into special collection libraries or museums and other institutions" (P10, Q29). Ensuring that preservation will likely be a self-undertaken project, in the way that all things fandom are.

8. Conclusion

[8.1] Fan binders continue the coterie craft practices that preceded fic production, challenging current assumptions of fic as exclusively digital and not bookish enough. They began binding fic because they love fan fiction and assign personal and aesthetic value to codex forms of fic. They reflect textual and artistic elements of the fic in their book designs, incorporating reader response into their fannish practice. Their affective labor presents an alternative driving force from profit-motivated book production, aligning the practice with fandom's gift-giving community ethos. Many of the binders reciprocate the labor of fic writing by gifting bound copies to fic writers, completing the fan fiction communication circuit. Bookbinders are concerned with the preservation of their favorite fics after having experienced fannish loss, historical repudiation of queer texts, and a desire to legitimize these texts to the outside eye. They trust fans and fan-adjacent entities to steward their libraries in the long term, underscoring the value of fandom community in not just producing and understanding but also protecting these meaningful works.

[8.2] Fan binding demonstrates that profit-based models for book production do not apply to every kind of book. Assuming that the codex is tied to profit ignores the meaning making in personal- and gift-based book production. Book history and fandom history together suggests that no textual form, material or digital, is stable and invincible. Preserving fic in print poses questions for where these works will go as their practitioners retire from the craft or die, and future studies could track private circulation of bound fic among fans, fic writers, and academic institutions. Additional research could examine with computational approaches the interlinking of these fic works with one another and with original artworks, as well as the aesthetic implications those examinations may have.

[8.3] The distance of fic production from the traditional publishing circuit does not disqualify it from book history but rather the opposite: fic text and codex production forces book historians to reckon with assumptions about the field. Incorporating fan fiction into book history provides insight into the fluid ways that people read and respond to textual encounters in print and digital form, and it introduces new models to consider book production, the value of information, and meaning making through both text and craft.

9. Acknowledgments

This article is adapted from my thesis for the MA History of the Book at the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, England. Sincere thanks and gratitude to the thirteen interview participants, whose insight and commentary on their fan binding practices enriched this research. Additional thanks to Christopher Ohge for helpful feedback.