1. Introduction: Toying and playing with history

[1.1] The past hides a wide variety of resources, and history is knowledge of the past. Through history, it is possible to rediscover what is already gone. History is not only used to remember the past—it is also used when orienting toward the future. "A historian must be at the same time an expert in information about the past, present and future," and history management entails all the means by which a historically and culturally active actor takes over the past (Suominen and Sivula 2012, translation by the author).

[1.2] The prime players of contemporary toy cultures are those fans who engage in activities that refine and remodel toys (and conceptions of them) as both physical and perceived artifacts and in this way influence behavior of other fans in terms of how commonly shared historical and cultural capital is toyed with through playful history management.

[1.3] Toy and game companies provide many forms of playable media for the enjoyment and consumption of fans. In addition to anticipating what the future of the industries of play (Heljakka 2013) bring to their fandoms, toy fans also look to and reinterpret resources of the past in many different ways. Toy fans acknowledge, admire, and actively remember the history of their objects of fandom, but they also participate dynamically in processes that come to influence and transform the nature of their own fandoms, sometimes even to the extent of how their objects of fandom are perceived.

[1.4] When discussing players with similar affections for certain toys, it is justifiable to address these player groups in terms of toy fandom. Previous research has identified the connection between fandom and play by recognizing, for example, ludic fandom in reference to game cultures (Mavridou 2017). "Fans' readings, tastes, and practices are tied to wider social structures" (Gray, Sandvoss, and Harrington 2007, 8). Indeed, the emergence of social media platforms has revolutionized how fans form online communities, distribute knowledge, and reinterpret the resources transferred and traded as part of their activities. It is also in lieu of these tools provided by technology that fans are able to toy and play with history—not only to remember but to make something memorable.

[1.5] Memory, a central concept for archiving and preservation (in other words, long-term fan capital), "has gone rogue" (De Kosnik 2016, 1) by falling from the state into the hands of rogues (a term originating in the work of Derrida 2005): the amateurs, fans, hackers, pirates, and volunteers. De Kosnik (2016) explains how digital culture cannot be thought about separately from memory-based making. The internet provides access to twenty-first-century rogue digital archives. How toy players as postmodern practitioners and makers of play navigate and operate in this context is through creative acts involving physical objects (playthings) and digital communication technologies (tools) distributed through online platforms (networks).

[1.6] Johnson (2014) claims that the focus of fan archiving has remained on the act of creation rather than on the forms in which the work is shared and an audience found. Swalwell, Ndalianas, and Stuckey (2017) similarly argue that much of the extant work on fandom centers around fans' role as prosumers in the digital era. While the questions of fan activities have therefore focused on consumption and creation, the preserving perspective of, for example, game historians, curators, and preservationists has received far less attention. Nevertheless, Swalwell (2013) notes how fans have documented and preserved games long before they were recognized as cultural artifacts worth archiving, and writes: "The efforts of game collectors and fans deserve recognition and respect. As amateur archivists, their efforts have been longstanding and often visionary." (n.p.)

[1.7] Mavridou (2017) argues that fandoms for games have a ludic dimension. Based on Caillois's (1961) conceptualization of paidic and ludic, the first refers to open-ended and creative play while the latter means a more rule-bound and goal-oriented form of play. To make a blunt distinction, toy players tend to lean on the paidic end of play while game players are more ludic in the playing. Newman's (2011) observation about the prevalence of game guides, cheat sheets, and walkthroughs (or, exploring the experiential potentialities of specific game titles) as important resources to game fandoms is similar to the creation of materials produced and shared by toy fans online. The presentations of the tools and techniques used in interaction with toys are restored as customization tutorials, collection walkthroughs (as examples of nonfiction), and documentations of play (as examples of fiction), and are distributed on platforms where like-minded players are likely to find them—namely blogs, websites, and social media services.

[1.8] Newman (2011) proposes that player-produced walkthrough texts as archetypical archival documents of gameplay might be more useful for future game scholars than the actual playable games. In a similar fashion, I argue that it is the documentations of play, which in particular emerge through photoplay (or toy photography [Heljakka 2012]) that, as informative fragments of play knowledge, should be acknowledged as documents of historical value. Following Baker's (2015) idea of the records of play entailing production and performance, the photoplay of adult toy fans functions as evidence of affective archiving of play culture, as well as mediators of play knowledge—how toys may be (or may have been) employed and cultivated imaginatively and creatively by their adult players as fans.

[1.9] As adult toy relationships continue to evolve around activities most commonly perceived as collecting (Rogan 1998) and hobbying (Heljakka 2017) by the fans themselves, it is possible to take into account the fact that object play has grown in popularity among adults as well. A materialist approach straddles affirmational and transformational extremes of fandom (Rehak 2014) and the "thingness" and physical habitus of fandom closely intertwine with the creation of play knowledge through material fan labor (Rehak 2017)—the craft, commodity, collection, and curation.

[1.10] Fans as collectors are well-represented in fan studies (Manning 2017). Toy fans of mature age collect, preserve, and cherish physical playthings in order to protect the original (para)texts of their fandom (Gray 2010). Toy fans, as indicated in the text of a 2011 brochure for toy store Super7, are the collectors and the variation hunters. However, and perhaps more interestingly, as stated in earlier research, it is fruitful to also understand toy fans as players (Heljakka 2017). On a metaphorical level, this follows Jenkins's mischievous notion of adult fans as rebellious children, for whom reading media texts and artifacts means to play with them (2006, 39). On a more practical level, the use of toys as part of play fulfills their primary function.

[1.11] Toys are objects that come to acquire symbolic content and meaning in a social context (Kline 1993, 143). Toys, just like games, gain meaning and significance when they are played (with). As historical artifacts closed in collectors' glass cabinets, they become detached from play and they are deprived of their full potential. In playing beyond hoarding of artifacts, they manifest as powerful entities that unleash imaginations and cater possibilities for both skill-building and storytelling for players of many ages.

[1.12] Adult toy fans constantly partake in creative cultivation of the meanings and physical form of the artifacts, by customization and personalization and by recreating, replaying, even retelling the stories connected to their beloved objects. Customizers try to produce the best version of beloved popular fan objects (Godwin 2015). These processes of manipulative and physically altering acts of recreation are simultaneously reforming the narratives and histories of fandom; new meanings and values are negotiated not only by the fans themselves but also by the fans of the superfans, who eagerly mimic the popular play patterns shaped and made perceivable through these exceptionally active individuals, who have achieved a cultural status among fans and consequently been named the prime players.

[1.13] Toys in terms of fan culture are often objects with cult status (Geraghty 2014). As collectors and players, adult toy fans are often interested in toy brands and characters with long histories that have established a permanent position in the toy market. Essential in these retro toy relationships to toys is a permanent emotional bond with the characters they represent. Perpetually relaunched toys attract players of different generations and thus afford ample possibilities for intergenerational interaction and therefore multidimensional meaning making.

[1.14] Adult toy players may have a long-term personal history with the toys, but it is key to understand that adults' relationships to toys are not only about a longing for childhood or nostalgia. The notion of nostalgia is considered as the main explanation for adult fans' interest and engagement with toys, just like in game cultures (Swalwell 2013) where this tendency transcends the limits of longing for retro games. Contrary to common belief, however, adults are not only interested in (re)collecting their childhood through historical toys. The collections of contemporary adult toy enthusiasts often include an extensive variety of toys—vintage, retro, and novel designs. It is also the toy characters themselves who through photoplaying actively engage with matters of the present like the author's own Ice-Bat Uglydoll figurines, for example, which campaigned on Instagram prior to the US presidential election in 2020 (figure 1). It is thus more fruitful to include the notion of player interactivity with toys in the investigations of toy fans' engagement with their stand-alone toys or entire collections, instead of focusing on preserving the artifactual nature of the toys per se.

Figure 1. A (historical) case of toy activism as an example of current forms of adult toy play. Katriina Heljakka, 2020.

2. Shared play knowledge as a resource for toy fandom

[2.1] Gazzard and Therrien (2018) ask: Beyond the preservation of the artefacts themselves, how can we preserve play? I take an interest in the activities of adult toy players, who actively preserve play, and in this way, partake in playful history management through their activities. I am concerned mainly with the role of adult toy players as fans who preserve play both online and off-line, and how they, in this way, participate in playful history management. When uploading content they regard as culturally relevant, the adult toy players of today act as (digital) rogue archivists. Making use of digital platforms makes the toy fans not only techno-volunteers as suggested by De Kosnik (2016) but also committed playborers, who produce entertaining, interactive, and informative content for others to consume (Heljakka 2021), such as toy photography or photoplay and videos, employing contents of toy players' collections.

[2.2] The notion of playbor (Küklich 2005) closely links with Price's (2019) idea of seeing nonprofessionals doing information tasks for leisure, even pleasure. In adult toy play, this information is interwoven into knowledge gathered, collected, shared, and disseminated for other fans. Baker writes: "DIY archives and museums share similar goals to national institutions with regard to preservation, collection, accessibility and the national interest" (2015, 47) at the same time observing how the project of archiving may have begun because of feelings of love and care and thus conceptualized as affective archiving. As much as the toy play of today involves skill-building, it is also an emotional investment by fans conducted for the enjoyment and education of other players, like the activities of music fans discussed by Baker.

[2.3] I suggest that the heritage and legacy of object relations of toy fans is preserved as play knowledge (Heljakka 2015b), meaning the documentation and sharing of play patterns associated with various toys. In the context of fans' ways to manage history, the concept of play knowledge becomes significant. For example, when playful scenarios of toys as part of displays, dioramas, or even doll-dramas are posted on Instagram, photoplaying is affectively archived to preserve not only toy history but also the history of play.

[2.4] At the heart of play knowledge is play value—the playability of a toy, which manifests in somewhat different terms than the playability associated with games, digital games in particular. Indeed, physical toys offer vast freedom for players in terms of their playability. Seemingly, there are no rules for toys as there are for games. However, matters such as physical materiality, aesthetics, and transmedia connections (Jenkins 2010) all play their part in interpretations of and interactions with toys. Toys considered meaningful for play in terms of their physicality, functionality, fictionality, and affective dimensions are regarded to have play value (Heljakka 2019), but it is the players whose performances actualize this potential. Thus, it is the toy players who actively partake in value creation. Players, through their toy play actions, are key agents in illustrating how fandom for toys manifests as affective, productive, and sociocultural engagements contributing to the formation of play knowledge.

[2.5] How toys are put in play in adult toy fandoms is essentially a matter of the fans themselves. Yet, the ways fans engage with their toys might be unknown or very different from the intentions of the toy designers and companies marketing the toy brands: Ultimately, the expectations about the ways in which toys are used are based on assumptions and can best be examined by specifying fan activities with the playthings. This includes inspection of information on how and in what context the toy object has been used and refers primarily to information related to play patterns. The museum approach often seeks to elucidate the uses of toys from a historical perspective. In contemporary play cultures, play knowledge is, according to my suggestion, based on and transferred by current documentations of play, which in essence capture the zeitgeist of object play here and now.

[2.6] In her study focusing on game cultures, Swalwell (2013) accentuates the relevance of the original experience for collectors and preservationists. Again, this original experience can be exposited through narratives and artistic appreciation. While many adults refuse to draw parallels between their collecting practice and play (Heljakka 2017), it is in their activities such as photoplay and the creation of displays, dioramas, and doll-dramas that their involvement in object interactions through manipulation, customization, and storytelling—in other words, play—becomes evident.

[2.7] The concept of play knowledge builds on the documentation produced, presented, and shared by the toy fans. Toys with a face and a designed personality are often connected to a transmedia property, illustrating their position as paratexts (Gray 2010) that originate in other realms of storytelling, such as comics, television series, or films. However, sometimes it is the character toy—doll, action figure, or soft toy or figurine—that is the original text, as is the case for example, with My Little Pony (Heljakka 2013; Heljakka 2015a) and many designer toys of the present. The so-called character toys have found their way into the fan experiences of players of all ages.

3. Twenty-first-century play patterns: Collecting and creating play knowledge

[3.1] Today's toys are colored by a variety of functionality; toy characters are collected, presented, and used as tools for creative and self-expressive activities in all age groups. Displaying of toys is an important form of play in both children's and adults' toy cultures. For example, various dolls that are particularly well suited for posing, fashionable dressing, and creation of elaborate hairstyles, such as Barbies, Blythes, and Pullips, are very popular with both children and adult players as displayed items. However, modern play with dolls is not necessarily limited to the collecting or manipulation of the toy itself—adult toy play is above all a communal activity and therefore represents play in its social form. In addition to mobile devices, the toy play experience involves playful interaction mediated on various platforms, such as (1) urban environments and nature (for example, attractions); (2) private spaces such as built environments (e.g., dollhouses, dioramas, and room boxes) and (3) social media play environments (Flickr, Facebook, Instagram). Cross media and transmedially inspired play that happens on multiple arenas and through employment of different fictional story worlds simultaneously—the physical space and the realm of social media—together with a toy that is rich in affordances of playability and thus communicates play value, forms an interesting field of research for fan scholars exploring the features of contemporary play and the processes underlying the generation of play value. Both the toy object—the mobile devices used in photography and videography—and the physical environments used for play, as well as the opportunities that invite players to engage with toy-related content on social media, have influenced the practices formed in play. In fact, the toy media, as well as mobile technologies, social media, and the playing fans, intermingle in the physical, virtual, and intertextual linkages of the ecosystem of play (Heljakka 2016). The dimensions of the toy experience—namely the physical, functional, fictional, and affective fan relations to toys—manifest in a multitude of ways within this ecosystem, in which the industries of play, the products for play, the players, and media technologies all influence each other.

[3.2] Earlier research with adult toy players states how mimetic practices such as photoplay (Heljakka 2013) manifest as a major play pattern for most toy fandoms, supporting the claim that play of the twenty-first century is not only technologically enhanced but largely an oculocentric, or vision-based, practice. It is not only fan fiction that is shared through play—play knowledge is disseminated through nonfiction content as well. While, for example, unboxing videos of toys shared on YouTube may be highly entertaining in aesthetic and even sensuous terms providing audiovisual stimuli, they contain relevant information for current fandoms, offering insights into what kind of affordances for play are held by new editions of dolls, action figures, designer toys, or plush with their mechanical dimensions as well as visual and textual narratives or backstories. Moreover, tutorials on toys' functionality are both cognitively and creatively informative, advising and inspiring fans to derive the most play value out of the toys. Sometimes, this nonfictional fan-produced content transmits tacit knowledge on hidden affordances, meaning features of toys that can only be discovered once the playthings are unboxed, explored in their mechanics, and sometimes even broken. Customization of toys is closely related to the recently strengthened maker culture, in which the object of fandom is given a personal look. Toy fans give each other tutorials through podcasts and vlogs on how to best customize and photoplay with the toys. For example, the customization of the Blythe dolls can involve designing, knitting, and sewing the doll's clothing as well as personalizing the doll itself through various activities—doll hair rerooting and styling, changing of eye chips, and painting face makeup (Heljakka 2012). These processes allow players, for instance, to transform their toy friends' appearances in radical ways—even in how their gender is perceived. Moreover, these traces of play knowledge offer a resource for other toy fans interested in physical alteration and creative narrativization of their character toys.

4. Methods and case studies

[4.1] In the following, a study focusing on qualitative interview data collected from three adult toy fans with a fandom for three different toy types is presented: Forest Families figurines, Star Wars action figures, and Barbie dolls. The motivation to study different types of character toys stems from the belief that despite their own followers, these fandoms and toy player communities share similar practices in their cultivation and employment of play knowledge, most prominently through photoplay. In order to grasp the practices of fans of toy figures, I explored two websites dedicated to the fandom of Forest Families animal figures: Forest Families Collector (https://www.forestfamilies.net/en) and Forest Connection (https://theforestconnection.weebly.com/). I conducted a brief online interview with Xara (the hostess for the Forest Families Collector website). Additionally, I interviewed Star Wars player Truupperi and Barbie player of Ellie from Finland. I asked the adult toy players about how and with what impact they disseminate knowledge about the past, through questions such as "What is the relation of your toys to the general history of the toy type?" and "In which ways, if any, do you think that your activities with the toy advances its history?"

[4.2] The interviews with players Truupperi and Ellie from Finland were conducted in two phases: the first as personal interviews during 2018, which were complemented with another round of interviews with the player of Ellie from Finland that Henna Kiili made online in 2020. The in-person interviews were carried out as play interviews, which from the author's side included participatory observation but also participation through shared play and photographic documentation of interaction between the interviewer's and interviewee's toys (figures 2 and 3). I also included the inspection of photographs posted on Instagram by these players in the content analysis.

Figure 2. The author's own Ice-Bat toys in a photoplayed scene made by interviewee Truupperi. Katriina Heljakka, 2018.

Figure 3. Ellie from Finland interacting with the Ice-Bats in her doll apartment (room box). Katriina Heljakka, 2018.

[4.3] The activity that ties contemporary play of fans with the work of researchers, archivists, historians, and others interested in knowledge about the past is the documentative aspect. Before engagement with the artifacts of fandom can be shared with others, interaction with them needs to be recorded. Today, perhaps more than ever, the toy-playing fans document their own play through, for example, fan art also recognized as fan works (Price 2019). In other words, play patterns, such as curating and displaying a toy collection and the practices of imaginatively and creatively active toy play—customization or personalization, photoplay, creation of serial doll-dramas, or visual and textual narrativization of the toys' lives and adventures, and toy tourism (or, toyrism [Heljakka and Räikkönen 2021]), such as indoor and outdoor adventures mobilizing the toy from the intimacy of the home environment into the public space, demonstrate types of adult toy play, where camera technologies and sharing on social media carry essential importance. By self-documenting and sharing their play activities with like-minded fan communities, the toy playing fans document their interaction with toys and come not only to create but also to preserve play knowledge. How precisely these forms of play relate to the fan work and more profoundly to the history work of adult fans as a form of playbor is detailed in the following sections.

5. Forest Families figurines: Reminiscing and restoring a happier alternative for toy fans

[5.1] The first example of toys employed in the history work of the fans is by exploring a brand of toy figures, Forest Families. According to a fan-run website, "Forest Families are a 1980's toy series, quite similar with the more famous Sylvanian Families. Forest Families toys are human-like animals covered in soft vinyl flocking, and the species vary from cats and mice to crocodiles and turtles" (Forest Families Collector). Today the figures are sought after among collectors and often sell for higher prices than Sylvanians. The scarcity of the figures of this 1980s toy brand makes the series a coveted case in toy history: "Forest Families are becoming increasingly hard to find, but also a more collected toy series" (Forest Families Collector).

[5.2] As illustrated by the fans' personal descriptions of their motivations to collect and display these character toys as demonstrated on the websites, their strategies of consumption rely largely on fan-authored and produced nonfiction of the past, as illustrated in a statement made by the Forest Families Collector: "There is still a lot of information to be gathered about them—rare variants, where they were sold, and so on." Both text-based and photographic information about the variations, past editions, and evolution of the toy brand in various countries are valuable matters for the adult fans as this information as a form of play knowledge is carefully detailed and exchanged. Furthermore, fans also send old toys as gifts to each other as they learn about individual preferences. The case example of fan interaction with Forest Families presents forms of edutainment—or educational entertainment—meaning "the process of entertaining people at the same time as you are teaching them something" (Cambridge Online Dictionary). In sum, as the investigation demonstrates, fan activities with a toy type of yesteryear, such as the Forest Families, manifest as knowledge-intensive play and preservation of the legacy of a historical toy brand—reminiscing and restoring as the first forms of play knowledge formulation.

6. Star Wars action figures: Humorous replaying strengthens fandom

[6.1] The second case study of the history work of fans centers around one of the largest entertainment brands—Star Wars. The role of Star Wars for toy culture as the first and largest brand of action figures in the history of toys as well as the supersystem of play is significant, if not epic. What started with a movie trilogy made famous by George Lucas stands today as a multidimensional universe of stories, characters, and related paraphernalia, such as various toys—action figures with accessories and vehicles. Star Wars has the biggest collector base of any (toy and entertainment) brand (Geraghty 2006, 217). The most collected Star Wars merchandise is the action figures (interview with Howard Roffman, October 19, 2011). Indeed, Star Wars has been considered "toyetic" (Gooney Bird 2011) from the very beginning of its history, meaning a particular suitability of the story world to be turned into (physical) playthings.

[6.2] One of the most prominent play patterns of mature players related to activities with Star Wars toys is the replaying of scenes from the films. Fans of Star Wars and its toyverse are mimicking or replaying scenes with toys, capturing them on camera and sharing these instances of photoplay online. Significantly, however, a large amount of photoplay on Star Wars is enhanced by the fans as they are adding a personal touch to their toy photography by introducing elements and details not featured in the original texts. These additions may appear as sets and environments specifically built and personalized in play by the fans (for reference, see figure 2), or as extra accessories given for the character toys, such as the Johnny Cash guitar added onto a photoplay done with Darth Vader by Truupperi (Heljakka 2018). The paratextual spatio-play (Williams 2019) or even more specifically spatio-temporal object play patterns of fans also make use of the fans' actual physical surroundings including outdoor sceneries, such as nearby landscapes, and the sometimes unique weather conditions non-existent in the actual and original filming locations, for example, those with real ice and snow (Personal interview, Truupperi, June 26, 2018). Alternatively, fans may turn their photoplay into dreamlike scenes by constructing elaborate sets and using polished techniques for special effects, such as toy photographer Vesa Lehtimäki, who has turned his Star Wars fan art into professional collaboration with the LEGO company. In this way, the personalization results from where the fan is replaying—the geography of play, locality, and seasonal effects on photoplay, and so on. The photoplaying of Star Wars with its humorous input—for example, Stormtrooper action figures gathered together to make a group selfie (Heljakka 2018)—follows Jenkins's notion of fan texts as parody: Jenkins notes that the overwhelming majority of fan parody is produced by men, while fan fiction is almost entirely produced by women (2006, 159).

[6.3] The entertainment that manifests as comical, scene-based still photography, sometimes enhanced with effects, represents episodic (and timely) toy play, as illustrated in a scene in an Instagram posted on December 24, 2020, where the action figures are decorating the tree prior to Christmas 2020 (https://www.instagram.com/p/CJL09n2ASu4/?igshid=ed69s2td48co). The relevance of the fan art conceptualized here as a form of adult toy play then, in terms of history work of fans, is in strengthening the fandom through remembering the legacy of the continuous saga that Star Wars is, but by slightly altering its original form through constant acts of skillful but humorous replaying, the second dimension of formation of play knowledge.

7. Ellie from Finland: Recreating Barbie in play

[7.1] Doll play has traditionally been practiced indoors, where toys have been assigned their own places as part of the intimacy of domestic environments, for example, in a dollhouse or diorama, or as part of displays (Heljakka and Harviainen 2019). The third example of history work of fans is a case study of Ellie from Finland, a Barbie doll.

[7.2] Barbara Millicent Roberts, more familiar as Barbie, is one of the cult characters of doll history. As a teenage doll character loosely based on the German adult doll Bild Lilli, her physiognomy was turned into the most popular doll type of the twentieth century by toy company Mattel in 1959. Despite being challenged by the more edgy Bratz dolls in the beginning of the twenty-first century, Barbie has survived and thrived as one of the most collected and creatively cultivated dolls in adult toy fandoms. Key to this historical position is Barbie's dual role as a toy industry-modeled representation of a young, successful, and quintessentially Western woman for whom anything is possible and also as a blank canvas for projecting artistic ambition and current world phenomena. Barbies have been reimagined in art (for example, in the Altered Barbie art show organized in San Francisco (http://alteredbarbie.com/) not only as drag queens or as Barack and Michelle Obama (Heljakka 2013, 323) but also as a recreated toyish representation of the contemporary hipster, such as in the case of SoCality Barbie (Heljakka and Harviainen 2019).

[7.3] These examples illustrate how Barbie moves effortlessly between the pristine figure of the stiff (non-articulated) 1950s teenage model and a dynamic, driven, and super-articulated action doll with a made-to-move body and a potentiality to be turned into a real personality: "It just happens to be the right size for my stories and Mattel happened to make a 2015 made-to-move body that bends to natural postures," says Henna Kiili, the player of Ellie from Finland (personal interview, December 16, 2020). She acknowledges the historical arc and narrative behind the brand:

[7.4] Barbie dolls were originally made for girls, that there would be other options than playing with a baby doll and that the player would be a mother herself. Boys got whatever toys that helped them to be astronauts, supermen, adventurers, etc. without limits, but the girls were housewives even in play. So, by that I mean that [earlier] the girls didn't even have options in toys. What a time to remember. (Personal interview with Henna Kiili, December 16, 2020).

[7.5] The playing of Ellie from Finland is all about photoplay enhanced with detailed and plotted storytelling, an example of fan-authored entertainment through a serial doll-drama (Heljakka and Harviainen 2019). The doll-drama is enabled by physical toy mobility, even toy tourism (or toyrism)—meaning outdoor excursions with the toy and documentation thereof, as well as digitally emerging creativity.

[7.6] This case of adult toy fandom expressed through actions of play represents the third approach to generation of play knowledge, namely recreation. In her doll-drama, Ellie from Finland goes through relationships with male dolls, meets the dolls of other toy fans, and enjoys her life with an amazing wardrobe in a beautiful (room box) apartment, with detailed miniature furniture and objects from around the world. Moreover, this doll-drama shared on Instagram features special effects, for example, added facial gestures (such as a laughing mouth to an otherwise serious face) achieved with suitable digital apps. The described activities show how the fandom for Barbie is everything that Barbie stands for but with a connection to real life (human) situations and aspirations of the contemporary kind—relaxed relationships, changing of boyfriends, the dilemma of having a family or not, experiencing occasional depression, and so on. In the case study with Ellie from Finland, it may be seen how Barbie in current fandoms is liberated from traditional female roles but also from the way of seeing Barbie as a children's toy:

[7.7] Through the things I've done with Ellie, I believe that Ellie can be anything and do anything. Ellie's life is not limited. Now Ellie is studying and working and getting to know new people (other people's dolls) and adventuring in Turku. That is, we return to Barbie's saying "You can do anything." (Personal interview with Henna Kiili, December 16, 2020).

[7.8] How the playing with Ellie from Finland represents history work of fans is in the fan-made play patterns as future materials of fan pedagogy: Ellie from Finland, through her player Henna Kiili, shares with and tutors fellow fans and players about the limitless creativity that a doll like Barbie may allow but only if recreated in terms of personality, appearance, living environment, and relationships to others (toys and humans). This illustrates how creatively customized and narrated Barbies utilized as part of adult play are genuinely different and therefore perceived as more human than perhaps a more limited, toy industry-communicated sense of who Barbara Millicent Roberts really was in the first beginning of her story.

8. Discussion

[8.1] Since the emergence of social online sharing, toys have broken out of the Wunderkammers and intimate cabinets of curiosities of their owners into the active sphere of engagement in the context of adult toy fandom and contemporary object play. In fact, content distributed on social media has come to form a window to the worlds of play even in the context of adult players. The value of toys for the players is largely based on their playability—how the playful potential of these objects may manifest through cultures of collecting, displaying, and creative storytelling, even toy activism. However, the real play value of toys is a factor related to subjective experience and therefore difficult to measure. Consequently, the examination of the diversity of play forms and creative outputs of toy fans becomes important, which will at least partly explain the realization of the intended (and sometimes unexpected) affordances and values associated with and generated by toy play in fandoms. Thus, collectively created and socially shared play knowledge becomes a telling, relevant, and historically informative resource for anyone interested in the active nature of the object relations in toy fandoms. Simultaneously, it is in this way the heritage and legacy of toy play is preserved.

[8.2] According to my previous observations (Heljakka 2015c), certain toys representing today's material play culture, such as dolls, plush toys, and action figures, also contain features that seem to offer their users greater opportunities for creative play. However, playful offerings are not exclusively about toys; for example, a camera or a mobile device can act as a means of facilitating play—as a kind of toy in itself—because of the photography it enables and the features that connect the device to social media services. Therefore, it is essential to note how it is the visual forms of play, such as making of displays and photoplaying, that play a significant role in making the phenomenon of adult toy cultures visible in the ludic era (Sutton-Smith 1997), an era that may, in fact, be understood as an increasingly paidic-oriented era, leaning more toward imaginative and creative endeavors than goal-oriented and competitive (ludic) outcomes recognized in games. Instagram, in parallel to YouTube, develops in this way into a shop window for creatively cultivated and actively used toy collections.

[8.3] I have investigated the origins of fandom for three types of character toys—figurines, action figures, and dolls—and how the relationships and works of fans have developed in the course of playful activities to contribute to the common play knowledge as a resource shared by fans interested in the preservation of the historical aspects of the toys—their material, narrative, and market-related dimensions, and perhaps most importantly the play that happens with them. The empirical study on Forest Families, Star Wars action figures, and Barbie has shown how fans trace and preserve historical facts about the histories of toys but also how they extend and enhance the fictitious aspects of toys, for example, toy industry-given backstories to brands in their interactive play activities.

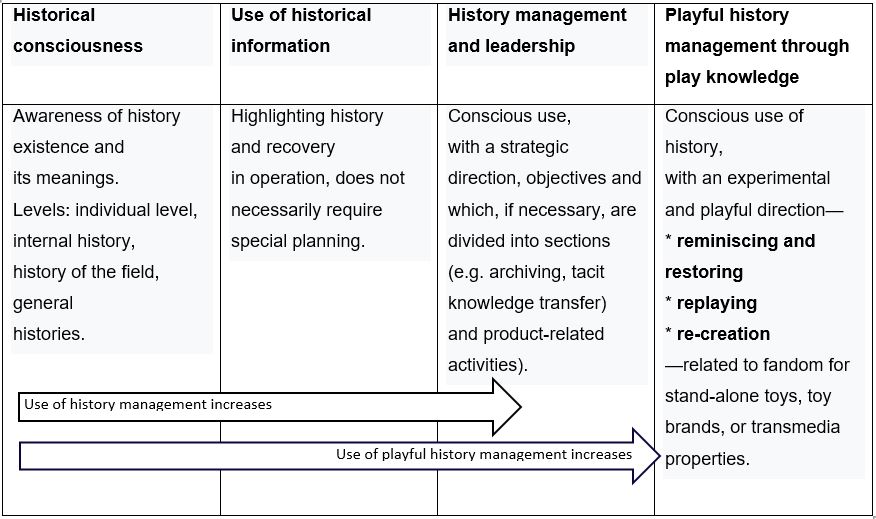

[8.4] Following the model on the levels of history management of Suominen and Sivula (2012) and based on the study at hand, toy fans are often historically conscious and keen to operate with the historical meanings of toys through, for example, documentation, archiving, tacit knowledge transfer, and toy-related activities. At the course of play, meanings associated with the toys are developed and sometimes even challenged. Based on these findings, I propose that toy fans manage history playfully mainly through three approaches and thus contribute to play knowledge in the following ways: by reminiscing and restoring knowledge (tracking down information of toy lines of the past, such as Forest Families, and in this way, function as authors of nonfiction media); by replaying (mimicking storylines based on narratives familiar from transmedia phenomena, such as Star Wars, but at the same time, adding their personal, creative, and at times even humorous touch to these toy stories and their consecutive histories); and by recreation (creatively cultivating new toy personalities out of existing physical toys, which are customized, narrativized, and dramatized and who with their authoritative players become cult characters for fandom in their own right). Based on these observations I have created a mapping of the perspectives of suggested playful history management in relation to fandom for stand-alone toys, toy brands, or transmedia properties, following the model of Suominen and Sivula (2012) (figure 4).

Figure 4. Levels of history management and playful history management through play knowledge generated in toy fandoms, based on the model of Suominen and Sivula (2012).

9. Conclusions

[9.1] At a time when new media makes it possible to share all kinds of stories quickly and efficiently, toys have become an expressive and notable media: the toy has become a tool that tells players a story. At the same time, toy media is a tool for fans and players of all ages to tell their own stories. Seen in this way, an adult toy relationship seems to be similar to a child's relation to a toy, but it also seems to include more structured, regular, creative, and productive activities such as photography that employ toys as inspiration, theme, and a material resource for adult toy fans.

[9.2] Social sharing is essential when considering the historically relevant nature of the documentations of play, and today the ways of distribution happen largely in the digital realm. It is likely that documentations of toy play, such as the results of toy photography, will in the future be considered as traces of information leading to interpretations of play culture of a particular time. In other words, they will provide a relevant source of play knowledge, capturing the otherwise ephemeral and probably vanishing cultural acts of play.

[9.3] Cavicchi (2014), in his explorations of the history of fandom in the predigital era, notes how investigations outside of objects and through images can lead us to see repetition of ideas and emerging patterns of reference. It is in this way, I suggest, that future researchers of toy cultures and fandom may access culturally relevant play knowledge of instances of play of the past—in the self-documented, photoplayed, socially shared, and digitally archived toy play sessions of adults, who in their time fancied toys and cracked the door open to their toy closets, collections, and collective creativity.

[9.4] In summary, today's toys fascinate fans of many ages, especially because they offer plenty of opportunities for wonder and both tangible and transmedially emerging exploration. When approached creatively, they become important tools for their players in self-expression and social play. In the case of Barbies, Star Wars action figures, and Forest Families, their original designers and manufacturers were perhaps unable to see how the (mature) players of the 2020s become inspired to use the toys in their creative play and that they would be surrounded by such a diverse, productive, and socially operating fan cultures as illustrated by the forms of adult toy play that I discuss. Adult players themselves as creationists of new meanings become objects of fandom as superfans and prime players, who inspire and invite others to play and consume—to fandom for toys. As demonstrated in this study, fans also have an important role in the generation, exposition, and dissemination of play knowledge.

[9.5] Fan historians accumulate cultural capital through play, but also enable the transferring of play knowledge to other toy fans, meaning reminiscing and restoring knowledge, replaying, and recreation of new content with meanings previously unimagined in association to the toy brands. By analyzing the history work of adult toy fans, it becomes possible to view these communities through the notions of playbor and playborers (Heljakka 2021) and for professionalized production of content on play knowledge for others to consume—creation of new layers of meaning to be projected onto the toys.

[9.6] Adult toy fans are the managers of historical play knowledge not only in terms of acquiring, archiving, and preserving artefacts but also in showing how they put them in play in present times. The superfans as prime players are responsible for formulating novel perspectives on use of historical toys in photoplay or toy photography. In their activities connected to toy play, collecting, displaying, and content creation, toy fans themselves are historians and history makers, and at the same time, historical figures of toy cultures and fandoms.