1. Introduction

[1.1] Carol, released in 2015 and directed by Todd Haynes, is a film adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's 1952 novel The Price of Salt. The film tells the story of two women who, following a brief encounter in Frankenberg's department store, begin a relationship with one another in the early 1950s. The pair take off on a road trip before it is ultimately revealed that they were pursued the entire time by a private detective hired by Carol's estranged husband. The film, marketed as a romantic drama, carries with it many of the suspense elements of Highsmith's original text. Indeed, these elements are only exacerbated by the audience's knowledge of the fraught historical context of queer life in midcentury America. In this context the couple is pursued not only by the detective but also by the expectations of tragedy from the twenty-first-century audience and a tradition of lesbian literature and cinema that affirms the assumption their relationship will meet with downfall.

[1.2] At the time of the film's release, many reviewers suggested that Haynes's meticulously created world allowed a means of access into the reality of queer lives past. The Guardian noted how the film "shows us the corsetry and mystery" of gay people's lives in the 1950s (Bradshaw 2015). The New York Times commented on how "like other historical fiction, it measures the distance between then and now" (Scott 2015), the Independent on how "richly textured cinematography gives us the sense that we really are back in the 1950s" (Macnab 2015). Rolling Stone magazine pointed out how "Haynes's commitment to outcasts, then and now, makes Carol a romantic spellbinder that cuts deep" (Travers 2015). These reviews demonstrate how the story of the film (that of Carol and Therese) is understood as a work of fiction, but the world they inhabit (that of corsetry and mystery) is understood widely as a factual and accurate portrayal of the queer experience in midcentury America—of what it was like then.

[1.3] Yet Carol, while being historical, is not factual. Patricia Highsmith's original novel is based on an encounter Highsmith herself had with a woman in a department store, and this encounter, expanded and fictionalized, forms the basis of The Price of Salt. As Patricia White has suggested, Carol does not focus on realism; it is not looking to document history. Instead, "Carol inscribes lesbianism within a textual and reception history" (White 2015). Carol is historical—indeed, screenwriter Phyllis Nagy insisted that the story must exist in the 1950s to have resonance (Baughan 2015); however, it does not present us with queer history as audiences might have come to expect it, as stories revolving around civil rights, legal cases, and losses.

[1.4] These differing approaches to telling stories about queer history are evident in the difference between Carol and Freeheld, also released in 2015. Freeheld is a film adaptation of a 2007 documentary that followed Laurel Hester, a New Jersey police officer, as she campaigned to have her pension benefits transferred to her long-term female partner after Hester's terminal cancer diagnosis. By contrast, Carol is a historical film both in its setting and also, as Mandy Merck (2017) argues, through its place in the traditions and histories of lesbian storytelling.

[1.5] With this in mind, I demonstrate how fans of Carol have expanded this vision of lesbian histories. The work of fans in this case is not that of historians, set on a path to discover the truth of "life back then"; they are not necessarily seeking to locate themselves in a lineage of queer history. Rather, they are becoming a part of the history of telling stories about queer history. I suggest that the motivations behind these histories can be best understood when framed through Elizabeth Freeman's (2010) erotohistoriography. Working across literature, film, and art, Freeman challenges the tendency of previous work on queer theory and the study of queer time and history to focus on queer pain and loss. Instead Freeman suggests a shift in focus toward bodily pleasure, culminating in the suggestion of erotohistoriography as a mode of historical study that does just this.

[1.6] Freeman defines erotohistoriography as "distinct from the desire for a fully present past, a restoration of bygone times. Erotohistoriography does not write the lost object into the present so much as encounter it already in the present, by treating the present itself as hybrid" (2010, 95). Fans, I argue, push and pull the characters of Carol through time to create their own vision of queer female history. This history is not one preoccupied with historical truth but one that is instead interested in the ways that visions of the past can be reimagined in the present and in the ways that these reimaginings can elide the experiences of queer women past and present, causing them to touch across time.

[1.7] In addition to hybridity, key to erotohistoriography is corporeality: "It sees the body as a method, and historical consciousness as something intimately involved with corporeal sensations" (Freeman 2010, 96). In an analysis of Hilary Brougher's film The Sticky Fingers of Time (1997), Freeman comments on how the tail of the character of Ofelia serves as a "device that leashes bodies to one another even across time…to seize, to grasp the past and bring it into conjunction with the present" (134).

[1.8] Erotohistoriography is then employed here as a framing for understanding the ways that fans interact with and create history. I wish to suggest that fans encountering history do so in line with Freeman's pleasure-led study of history and that they also expand it to consider more widely what queer eroticism across time might look like. The result of this seizing and subsequent reshaping is to demonstrate how fandom can help rethink approaches to queer history. It demonstrates how the poaching viewed as innate to fandom can create visions of queer history that are participatory, defined by the desires of those who consume them—desires that center queer community, visibility, and reimagined eroticism.

[1.9] The contents of this erotic archive are demonstrated through the analysis of memes, fan fiction, and fan merchandise. Working within three key areas of fan work in the Carol fandom, the sections "Carol Season," "Mommy's Baby," and "Harold, they're lesbians" explore the ways that these threads of fandom embody fictional bodies, experience erotics across time, and reimagine queer visibility across history. My analysis of the memes and memetic responses to Carol builds on the work of Limor Shifman (2014) in conceptualizing memes as a pertinent area of study, "treated as (post)modern folklore, in which shared norms and values are constructed through cultural artefacts."

[1.10] For the purposes of this work, Eric S. Jenkins's (2014) work on how to approach the analysis of memes is utilized. Jenkins calls for a "shift in emphasis away from the examination of distinct texts and contexts to a focus on the manners of engagement…that audiences don't merely 'read' texts but interface with them." Jenkins's focus on analyzing the ways that memes travel and how audiences interact with them, in addition to their content, allows for a framework applicable to all the sources covered here, not just image-based meme responses.

[1.11] This mode of thinking is applied here, tracing the trajectory of fan themes across platforms to follow different branches of fandom but also to examine what it means for fans to meet and interact over various platforms, activities, and texts. Subsequently, each section has a particular emphasis on a thread of Carol fandom, and there is on occasion an interweaving of fan work to allow for identification of the ways that these strains overlap and intersect in their motivations, intentions, and impacts.

2. Ethics

[2.1] Before commencing this research, I gave consideration to the most appropriate way to approach consent and privacy. Ultimately, the research done and presented here is low risk and presents minimal harm. I arrived at this conclusion through consideration of the principles outlined by Heidi McKee and James Porter (2008). When I discuss Instagram and Facebook posts, the accounts I have chosen have large followings of readers, and neither the user's handle nor the content discloses who is behind the account (similar perhaps to how a brand or business might operate on the platform). These accounts are public and easily locatable, so sharing their content in this study does not pose a danger to the poster.

[2.2] With this in mind, I decided not to analyze the comments on these posts, and all comments have been redacted from images. This is because I believe the comment sections on these posts constitute what Elizabeth Basset and Kate O'Riordan (2002) have termed a "semi-private" space. Although the comments can be viewed by anyone visiting the posts, the accounts used here are dedicated to sharing queer female-oriented content; including the commenters in this research would place them in a vulnerable position. Moreover, as my focus is on fan trends as opposed to the opinions of individuals, analyzing these comments would pose an unnecessary risk.

[2.3] To assign credit appropriately, I feature the usernames for accounts when a particular meme is discussed that they originated. However, I had two primary reasons for not contacting the users behind each of the public pages. First, as stated previously, these accounts were clearly created to be public-facing accounts, so they do not represent private creative content. Second, the purpose of my research was not to understand the motivations of the individuals creating posts but to examine the posts themselves. My intention is to focus on the journey of the meme: what is pertinent is the fact that a post was made and shared on a large, public-facing account, and in various ways its themes were taken up and reinterpreted by others.

[2.4] The situation, however, differs when considering the ways to present fan fiction. Again, all of the content referenced was found through a Google search with no login required to access it. Yet there is a distinct difference between the platforms of Instagram and An Archive of Our Own (AO3). Instagram is an app owned by Facebook with somewhere around a billion users, and AO3 a website run and maintained by a community. Again, as with the memes, what is of pertinence is not individual opinions but instead the wider movement of a trend. As such, the work of individuals is not used; instead, the wider trends in stories are analyzed.

[2.5] Finally, it is worth noting in the vein of Alexander Doty (1993) and Matt Hills (2002), my own relation to this content. Although I have not been part of the Carol fan fiction community, I have and do follow and interact with Carol-related content on Instagram and Tumblr. Indeed, it is this interest in and interactions with these fannish actions that initially led me to include this in my work. It is thus pertinent to state that my views and analysis are not unbiased and that the sources I have selected may have been colored by this. However, this investment in these fannish pastimes allows me to approach these various texts with a sensitivity and understanding that might be lacking from another researcher. This is not to say that my experience of this fandom is indicative of all of those that are a part of it, but merely to say that it will allow me a particular route into it.

3. Carol season: Embodying the historical

[3.1] In December 2018 the online streaming service Netflix released on its YouTube account a series of "Carol Movie Sing-Along" videos (Away in a Toy Shop | Carol & Therese Sing-Along | Netflix 2018a, 2018b, 2018c). The series parodied well-known festive songs including "Auld Lang Syne," "Hark! The Herald Angels Sing!" and "Away in a Manger." The videos were performed by a cappella singers dressed in costumes resembling those of Carol and Therese when they first meet in Frankenberg's.

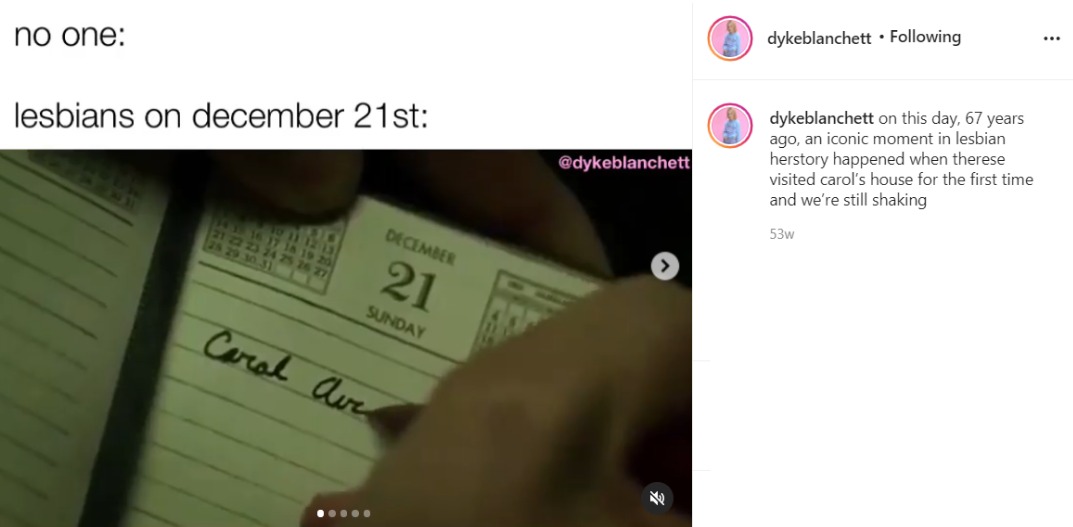

[3.2] The videos, created to promote the release of Carol on Netflix, made use of a preexisting fan dialogue around "Carol Season." The understanding of Carol as a Christmas film but also as a part of a wider season of celebration has been cultivated by fans through the sharing of memes, cards, and other social media interactions. One popular Instagram account, godimsuchadyke, has previously made cards that allow people to wish one another a "Happy Carol Christmas" or "Happy Holigays" (figure 1). In the caption for another "Carol Season" themed meme (figure 2), user DykeBlanchett states, "'Tis the season to celebrate the single best contribution to the 50s lesbian community, carol aird's lost leather glove." Another meme showing Therese's diary as she writes in the date of her meeting with Carol is accompanied by the caption, "No one:…Lesbians on December 21st."

Figure 1. Screenshot of a meme from the Instagram page godimsuchadyke.

Figure 2. Screenshot of a meme from the Instagram page Dykeblanchett.

[3.3] In Netflix's YouTube videos, the characters of Carol and Therese are brought into the present, reanimated through the singers' donning of what Freeman (2010) might term "temporal drag." The costuming is indicative of another era although the performers' multiple identical, ill-fitting outfits and plastic wigs bring to the fore the falsity of the moment. These are not women from the 1950s, but they are versions of the historic Carol and Therese, brought into and embodied in the present. This video, although not created by fans, nonetheless highlights the desire that drives this fan-led erotohistoriography: namely, to bring queer stories into the present, unconcerned by the specific actualities of the past but interested in the ways that this history can be reimagined in the present.

[3.4] The statement made in DykeBlanchett's caption that "'Tis the season to celebrate the single best contribution to the 50s lesbian community, carol aird's lost leather glove" binds together these past and historic queers, joined together by Carol Aird's lost leather glove and the sequence of events that its loss and return creates. Alice M. Kelly (2020) has suggested how fans make work of the pleasure of surfaces present in Carol. The pleasure of surfaces is utilized here also, with the authoritative dropping of Carol's glove onto Therese's counter, cast aside from Carol's fretting fingers and becoming, to the knowing viewer, a gauntlet placed toward Therese.

[3.5] In DykeBlanchett's statement, this glove, in its placement and passing, becomes a moment important not just because it brings together Carol and Therese in the past but because this action impacts the entirety of the "50s lesbian community." This tactile encounter becomes a moment of celebration for present queers as they enter into a shared time line of action and celebration with Carol, Therese, and the 1950s lesbian community. Indeed, in the phrasing of the Instagram caption, these communities are barely distinguished from one another as both are brought together in the action of celebrating the season.

[3.6] A further meme celebrating "Carol Season" shows Therese writing a note in her diary for the day that she will first visit Carol's home, December 21 (figure 3). The meme suggests that this too has become a practice for present day lesbians. On December 21 they will also visit Carol Aird by rewatching Carol. By following the actions noted down by Therese, fans place themselves within the time line of these characters, once more eliding actions past and present. In this meme, Therese's hand becomes that of all lesbians, each committing themselves to this particular time and action. In both these instances, fans place themselves within a historic lesbian community that is happening now, brought into the present by these moments of communal experience. Fans who are "still shaking" write themselves into this time line, the impact of this moment felt viscerally across time.

Figure 3. Screenshot of a meme from the Instagram page Dykeblanchett.

[3.7] In their analysis of nostalgia, irony, and collectivity, Bjørn Schiermer and Hjalmar Carlsen (2017) highlight the ways that nostalgia and ritual take place as individualized, mediated rituals. Drawing on Benedict Anderson's work on "imagined communities" (2006) they suggest that we constantly share "collective moments through 'replicative' or imitative use of mass media and shared objects" (Schiermer and Carlsen 2017, 163). "Carol Season" revolves around such replicative moments; facilitated through fan-made media, these create a sense of ritual and community. Here, Christmas is replaced by the festive "Carol Season," a season for enacting traditions similar to those of Christmas, but altered. "Carol Season" creates a queer, female space that exists outside of but alongside Christmas.

[3.8] If the work of erotohistoriography is to encounter the past as already in the present, and to do so focusing on feelings of pleasure, then the traditions of "Carol Season" do just this. By embracing Carol as a Christmas film, fans bring into the present not just Carol but all those traditions both Christmas and Carol-based. The enacting of such tradition suggests a history of past Carol Seasons collapsed into the present moment by invoking the idea of tradition. Subsequently, particular dates are noted down in the present because they were noted down in the past, and it is this very repetition that is pleasurable. "Carol Season" takes Christmas traditions and imbues in them queer pleasure, a queer pleasure not just at encountering tradition but in creating it.

[3.9] The question remains though, why has Carol, which was marketed as a romantic drama, been adopted by fans as specifically a Christmas film? The film itself is missing many of the hallmarks that might be expected of a Christmas film—it is not overrun by cheer and good feeling, and no one is reminded of the true meaning of Christmas. In her analysis of four 1940s Christmas films, Carolyn Sigler (2005) highlights how in films of the 1940s Christmas creates a space to be nostalgic about the values and ideals of prewar American society. Sigler highlights how these genre-defining films focus on that which war threatened most—"peace, family, abundance, tradition"—and how the repetition of these films and the values embedded in them have become an integral part of the ways that Christmas is represented and experienced (346).

[3.10] Carol is lacking in all the features present in these genre-defining films, with characters who eschew family, abundance, and tradition in favor of their insular road trip, which has very few material indulgences (bar the taking of one presidential suite, due to its attractive rate). This is not to say that Carol is the only film that has been recast as a Christmas film by fans (the debate around whether the film Die Hard [1988] should be regarded as a Christmas film has received much attention in popular criticism, so much so that arguably the annual act of relaunching said debate has become in and of itself a festive tradition for some), but it is to say that fans are actively electing to view Carol as a Christmas film. By eschewing a Christmas defined by family, peace, and abundance, fans demonstrate how tradition can be rethought in ways outside of heteropatriarchy. The combination of Haynes's window to the past alongside fans' continued reiteration of the traditions and importance of "Carol Season" blurs the boundaries between moments of remembrance about Carol Seasons past experienced by fans and moments of remembrance about queer lives and experiences from the past.

[3.11] One Instagram post from the dating app Lex does not just elide these communities through physical experiences and tradition but, in a way similar to that of the Netflix Youtube videos, "puts on" and becomes the character of Therese (figure 4). A screenshot from Lex places the poster in the position of Therese, searching for Carol. The user describes themselves as a "photographer, bottom…obsessed with you" and states that they are in search of "you: in the midst of a divorce, top, older woman." With this ad, the original poster makes use of Carol to create a specific dialogue with other queer women who are fans of the film, who are therefore able to understand the oblique reference to the film.

Figure 4. Screenshot of a post shared by Lex.app on Instagram. The post shows the screenshot of an ad posted on the Lex dating app.

[3.12] This embodiment and animation of Therese on the side of the poster, but also the invitation for someone to step into the role of Carol, places the contemporary audience within the roles of these characters; the reiteration and adaptation of them (the names of the characters are never mentioned, nor is Carol and Therese's original 1950s setting) also allows for the placing of contemporary desires onto this history. There is undoubtedly a pleasure in being able to recognize these descriptions as specific references to Carol, of being in on the joke and therefore being invited into a community of like-minded fans. Beyond this, the ad makes use of the ways that queer female erotics can align communities across time and how fans have used the erotic dynamics of Highsmith's original text to create a present moment of erotic hybridity: moving beyond ways to embody the actions of these characters, to using Carol and a history of lesbian eroticism as a means to connect with history.

4. Mommy's baby: Time-traveling erotics

[4.1] The Lex ad created by user film_thot creates connections between queer women, be they via seeing the original post on Lex or by seeing it when film_thot reshared it on further platforms, subsequently marking it as a point of shared connection and experience among fans. Beyond this, when thinking about erotohistoriography, of particular note is the way that the ad makes use of the eroticism in Carol and Therese's relationship, an eroticism fueled by their age difference and the perceived power imbalance that arises as a result of this.

[4.2] Carol and Therese first meet as Carol restlessly peruses the children's floor of Frankenberg's department store in search of a doll for her daughter. Behind Therese, as she offers Carol the worrying news that Bright Betsy is out of stock, sits a display of children's dolls. A sign describes them—and by virtue of its positioning, Therese—as "Mommy's Baby." This marks the first of several allusions in the film to the similarities between Therese and Carol's daughter Rindy.

[4.3] These allusions and their consequences are laid out by Mandy Merck in her 2017 article "Negative Oedipus: Carol as Lesbian Romance and Maternal Melodrama." Through a combination of the film, the original source text, and Highsmith's biography, Merck outlines the themes of mother/daughter intimacy that persist in both the film and novel. However, Merck argues, though this theme does appear in the film, much has been done to negate the more overt references present in the novel—part of the "negation of the novel's perverse origins" (2017, 19).

[4.4] Merck states that the film's dual use of both romantic and maternal melodrama are integral to its creation, as the maternal continually threatens to disrupt the romantic and the romantic plot is laden with maternal connotations. Merck argues that this tension is resolved in the film in a way perceived as more palatable than in the original novel. Carol "appeals for the lesbian right to motherhood" as she refuses to live "against her grain" and conform to the demands placed upon her by her estranged husband's attorney (2017, 21). As Merck highlights, this is in contrast to Highsmith's original novel in which Carol relinquishes any right to see her daughter so that she may continue to see her lover. In Haynes's adaptation the audience is assured of Carol's maternal affection for her daughter and, by the time of their reunion, of Therese's position as an equal partner in the relationship, demonstrated by her mature wardrobe, hairstyling, and successful career. As Merck concludes,

[4.5] The film's answer to this ethical quandary is to disavow it, counterposing the likely loss of the daughter at midcentury with the consolation of contemporary custody. The prospect of the mother's sacrifice is postponed beyond the conclusion, to the more liberal present of its spectatorship. The plot of the melodrama is enacted—but without the price. (2017, 28)

[4.6] Merck identifies the varying temporal iterations of the film's content as the main driver behind this ending. Merck suggests that it is an assemblage of views formed by the psychoanalytic theory of the 1950s favored by the author, the search for historical realism by the twenty-first-century director, and the perceived, "normative" desires of a twenty-first-century audience. However, as Eve Ng (2018) explores, fans of Carol can be seen as actively engaging in paratextual creation that denies the universality of the film.

[4.7] One such way that fans have denied this universality and the ethical quandary described by Merck is by creating content in celebration of this mother/daughter melodrama. This can be seen in fan posts as well as in the exploration of power differences and dynamics in multiple fan fictions. The result of this is that fans create their own present moment assemblages. They take the object of the past—Highsmith's original text and its "perversity"—and its contemporary reiteration in Carol, and through their play they create work around the theme "Mommy's Baby," which enacts all these at once. The impact of this particular assemblage is to allow fans to reshape the story of the history of lesbian eroticism. Beyond connecting with characters through the repetition of their actions, the connection to and subsequent reiteration of this eroticism allows for a connection in the act of its retelling and reshaping.

[4.8] In this context, "Mommy's Baby" will be used to group fan creations or transformative works that reference directly the concept of negative oedipal relations as well as those that rely upon a power dynamic created through the age difference of the two central characters. Although content creators might not use the phrase "Mommy's Baby" in their work, this theme is prevalent in several fan works, so for ease of discussion here they have been grouped under the banner of "Mommy's Baby."

[4.9] Explicit enactments of this theme can be seen in Instagram posts by large meme accounts such as godimsuchadyke. One post features a still from the film: in it, Blanchett is poised behind Mara, as Mara sits at a piano ostensibly about to play (figure 5). The pose, reminiscent of pulp fiction covers of the 1950s and 1960s, alludes to the erotic connection between the two women. The text below the image reads: "When Mommy promised you a piano lesson on Christmas eve if you were a good girl and helped her wrap the train set and went around to buy her a pack of cigarettes. They seriously should have called this film Mommy's Baby."

Figure 5. Screenshot of a meme from the page godimsuchadyke

[4.10] Any viewer familiar with the film will be aware that the text bears little similarity to the film itself. There is no promised piano lesson, the pair do not wrap the train set together, and Carol explicitly tells Therese that she does not have to buy her cigarettes. All these elements are present in the film but are here transformed to play into a narrative focused on instruction and subservience. This alters the image to link it explicitly with the sexual tension between the two women, but beyond this the caption actively plays with the scene to reimagine it as one where this tension is brought to the surface and made the prevailing emotion. The original scene is a subtle exploration of the two women traversing their feelings for one another as they, and the audience, seek to find a footing in their relationship to one another, but this post eschews subtlety in favor of pulpy sexual drama.

[4.11] Of note too is the use of the "mommysbaby" hashtag. Where hashtags on Instagram are usually used to draw together posts and conversations revolving around a specific theme, clicking through on this hashtag brings the user to page upon page of photos taken of young, photogenic children by their doting mothers. What then is the result of this post appearing here? Arguably the use of this hashtag serves to disrupt these heteronormative understandings of family and relationships. Although the cast and director might say that this story is a universal one, one in which all can see part of themselves, this action by queer content creators deliberately sets queer female relationships apart from such heteronormative narratives. In this context, it is made perverse. The historical image of queerness is brought into the present to intrude upon the contemporary, to question Who exactly is Mommy's Baby?

[4.12] This discussion is not limited to Instagram, but has also gained traction in fan fiction. In regard to Carol fan fiction, recurrent tags are "age gap" and "older woman/younger woman" but also tags such as "teacher-student." Notably, many of these works take place in various decades, with the majority taking place in the past and with a few present-day incarnations. There is a connection with the characters and their relationship that is viewed as relevant both at the time in which the author is writing and also at the time in which the fiction is set. Writers pull this erotic dynamic and Carol and Therese's relationship through time, demonstrating that it is relevant in any number of time periods, not just the 1950s. In keeping with the principles of erotohistoriography, this time-traveling eroticism is used as a means of communicative historical engagement, binding together past and present as fans find pleasure in imagining what queer eroticism looks like across time.

[4.13] Writers of these historical fan fictions, which take Carol and Therese as their inspiration and transplant them into another era, present this dynamic as not bound to either the moment of its original creation, the 1950s, or to the moment of its current iterations; they recognize queer pasts as the result of hybridity, of happening at multiple instances and wishing to connect with these, in this circumstance through bodily encounters. It is these bodily encounters that make these stories legible and valuable to readers and audiences.

5. Harold, they're lesbians: Queer (in)visibility across time

[5.1] Bodily encounters—and for queerness to be recognized as such—take precedence in the final key Carol fan work, "Harold, they're lesbians." This particular theme has been largely attributed to one particular post on Tumblr by user thcully in December 2015:

[5.2] I really don't know what crowd I expected to be in the theatre for carol at 1:20 in the afternoon on a friday but it was probably 85% old people, old het couples and halfway through the movie this old lady in front of me turned to the old dude next to her and just said "harold they're lesbians." (thcully 2015)

[5.3] The post itself garnered over 100,000 reblogs on Tumblr and started a meme that, as Ng (2018) suggests, "transmuted into an affirmative, even emphatic assertion about Carol and other media texts for which the meme is used: these characters are definitely lesbians" (17). To expand on Ng's argument and demonstrate how this work fits into erotohistoriography, I suggest that as well as becoming an assertion and call for lesbian visibility, this stream of fan work becomes so through the way that fans grasp onto queer pleasure. This pleasure arises from being seen and not seen, and how through the repeated act of making visible historic queer experiences fans make for themselves another version of history.

[5.4] In her book Immortal, Invisible (1995), Tamsin Wilton explores the experience of lesbian cinema spectatorship. Wilton places emphasis on the act of watching, on the "sensory/social experience of sitting in the darkened cinema, temporarily disembodied" (146). This experience of lesbian spectatorship—of examining what it means to be a queer viewer "sat in the dark with a number of strangers" and to consume queer content alongside said strangers—is a key concern of thcully's post and its appeal. Wilton suggests that there is a pleasure to be gained from sitting in this darkened room, yet this pleasure is always experienced alongside the potential for "recoil"—an abrupt return to the viewer's social location. Instances of this recoil, Wilton suggests, might be the inclusion of queer sex scenes, at which point the queer viewer might become acutely aware of the reaction of heterosexual audience members. However, these moments of recoil can also be pleasurable; for example, Wilton highlights the ending of Desperate Remedies (1993) as a moment where the film's ending left Wilton looking "with triumph around the (largely heterosexual) audience, my own deviant choices validated" (1995, 146).

[5.5] It is a similar queer shock and recoil that thcully describes: having already accepted the surprise of the audience members, thcully is abruptly brought back into their social location by the comment of Harold's companion. Through this comment, the queer viewer is dragged back from their consumption of queer pasts and into the present moment by a comment that establishes for them the apparent invisibility of lesbian identities. However, the comment by Harold's friend binds Carol, Therese, and thcully, uniting all three by their shared invisibility. Yet although Carol and Therese have been outed, presumably by physically making visible their lesbian relationship, the viewer, disembodied by their viewing experience, remains unknown.

[5.6] I would suggest that the levity of the post comes not from the initial moment described but from the knowledge that when recounted it will be to an audience of like-minded individuals who will be able to recognize this experience and who will see the humor in it, because who would not know that Carol and Therese were lesbians? The idea that queerness can only become so when made physically visible is challenged by fans in the reiterations of this meme. The way that the meme comes to be applied serves as an affirmation of queer identity while simultaneously allowing for fans to question what is necessary for queer history to be deemed as such.

[5.7] The continued repetition of the meme speaks to a desire for queer pasts and identities to be recognized, but more than this, for this recognition to be done through a queer act of looking and recognizing—for queer people to inform Harold that they're lesbians. What starts as a moment of shared invisibility transforms into a collective action to reimagine stories and histories as queer. Indeed, as Eve Ng has highlighted, the Harold meme was applied to a variety of popular programs and films to demonstrate queerness where perhaps, through the lack of physical confirmation of it, might have gone unnoticed by a heterosexual viewer (2018, 16).

[5.8] One popular example sees a Victorian image of two women leaning on one another and a museum caption that states the two were "lifelong companions" and the accompanying comment from a Twitter user: "They're lesbians, Harold." Similarly, a Facebook meme page called "Harold They're Lesbians" shared a meme telling the story of how the poster's father could not fathom how his elderly aunt and her best friend lived in a one-bedroom apartment together. The impact of drawing attention to such statements through the "Harold, they're lesbians" meme serves to ask questions of what kind of corporeal experience is needed to make queerness visible.

[5.9] It could be argued that this meme has little to do with the physical pleasure and eroticism that defines erotohistoriography. I would suggest, however, that the examples in which it is employed, often examples where evidence of a physical relationship is lacking, asks those interacting with the meme to consider instead that queerness can expand beyond this. The suggestion instead is that eroticism and intimacy, such as that explored in the Mommy's Baby meme, be evidence enough of queerness. These sources are defined by a perceived lack of physical connection that might make certain their queerness for the heterosexual viewer (if it is not seen it cannot be believed). However, these memes contest this. Pleasure is found in the act of making lesbians visible across time, the pleasure arising from a feeling of intuitive and intimate knowledge of what queerness might look like. By highlighting unacknowledged examples of historic queerness, contemporary queers share in this knowledge and their ability to reshape stories of what this queerness looks like, moving from "lifelong companions" to lovers.

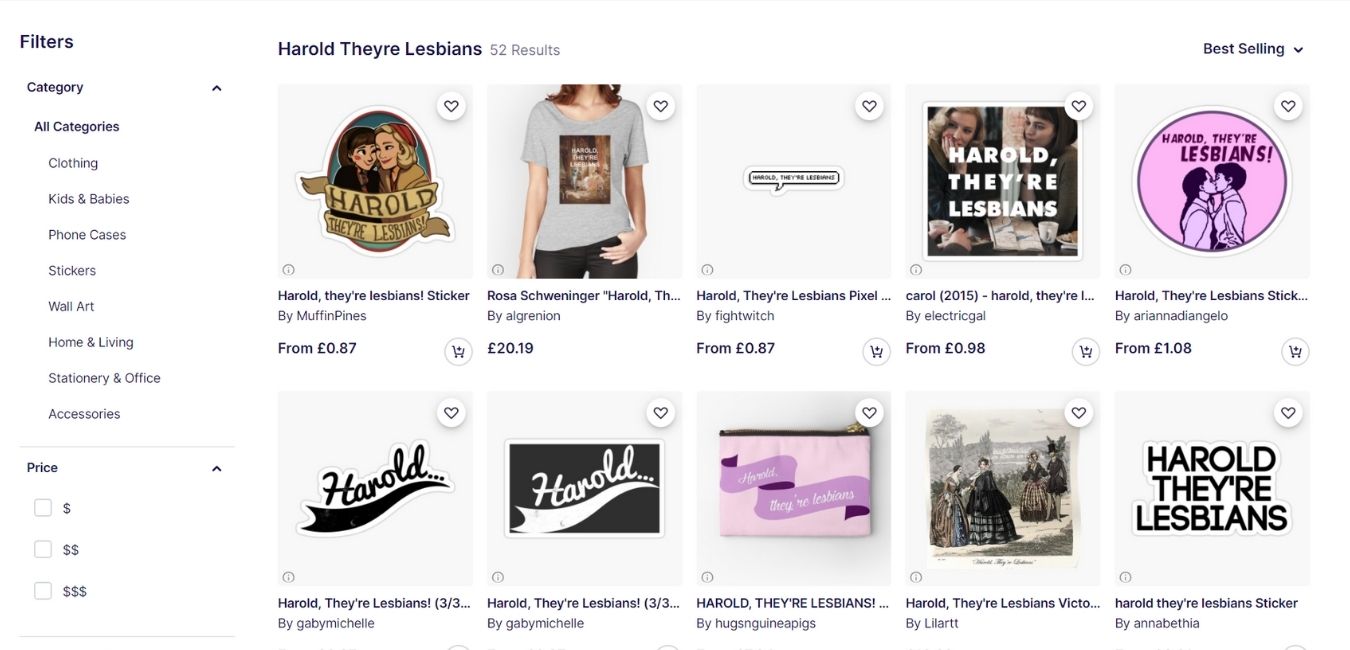

[5.10] This pleasure can also be seen in the way that "Harold" has been taken up in fan merchandise. Organizing a search on Redbubble by "bestselling" shows that the most popular items are not only those that feature images from Carol but also products such as a T-shirt with a painting by Austrian painter Rosa Schweninger depicting two women lying together on a couch, a vintage style sticker with a silhouette of two women kissing with "Harold, they're lesbians!" written across the top, and a painting of Victorian women walking together and "Harold, they're lesbians" written below (figure 6).

Figure 6. Screenshot of a search for "Harold They're Lesbians" on Redbubble.com.

[5.11] What is notable about these items is not only that they continue with the work of making historic queerness visible in the present but also the fact that the objects that are favored are items such as stickers, T-shirts, and home furnishings. Although a buyer might not have come across these items through a fan community, wearing a T-shirt, sticker, or pin signals to other queer fans their queer identity and their knowledge of this particular fandom. This act of recognition once again becomes an act of intimacy through the knowledge about another's identity it conveys.

[5.12] This is furthered by the fact that many of the bestselling items feature only the name Harold. This total removal of the meme from both the context of Carol and the latter end of the quote, "they're lesbians," makes the significance of this reference indecipherable to those not partaking in fan cultures surrounding Carol and other queer female content. The obliqueness of this reference works to counter the original narrative of the Tumblr post. Once where the phrase "Harold, they're lesbians" was evidence of the invisibility of lesbian identities, the creation and purchase of such items reasserts the continued presence of queer female identities in the present moment but also continuously calls back to the original moment of historic invisibility, uniting them across time. It is this act of repetition, also present in "Carol Season," that acts not only as a means of bringing forth queer pasts but also as a means of bringing to the fore queer pleasure. Through the use of Harold stickers, T-shirts, and pins, fans create for themselves a space where they are visible but not, making themselves known only to those who know.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] I have sought to demonstrate how fans of Carol have played with the vision of history it presents, the fandom taking Carol to create new visions of the past, using the principles of erotohistoriography. This archive encounters history in the present through touches across time, with touch and eroticism being understood varyingly across fan works. In the rituals of "Carol Season," the emphasis on communal acts of repetition creates pleasure in the sense of community found both in the present and also with the "50s lesbian community" of the past. In spaces where fans may have perceived themselves and their histories as invisible, the repetition of stories and actions makes them visible both at once, using historic invisibility as a means of connection in the present.

[6.2] The fan actions explored here mark a desire for unbinding from linear narratives of history in favor of seeking connection and similarity with past communities, which come to be represented through Carol and Carol's own history across time. For example, where the makers of Carol elect to distance the film from Highsmith's original preoccupation with the maternal/erotic bond between Carol and Therese, fans have sought to heighten this theme and bring it to the fore. The refraction of this eroticism across time and its subsequent enaction in the present allow fans to locate themselves within the lineage of the history of queer desire, while simultaneously having the ability to decide what the telling of this history will look like in the present.

[6.3] Although Haynes's film provides viewers with a specific vision of what life as a queer woman in midcentury America looked like, fans continue to pull and push Carol and Therese through time, to use them as touchstones for queer connection. They are unwilling to settle for a static understanding of queer female history but instead take Carol as a device to explore how visions of the past can be altered with cross-temporal communality at their core.