1. Introduction

[1.1] Printed fan fiction has a history as old as fandom. Fans first circulated fan fiction and other fandom content in printed booklets called fanzines. Francesca Coppa (2006) identifies the first science fiction fanzine as The Comet, published in 1930, and notes the popularity of media-property fanzines based on Star Trek (1966–69) and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1964–68) through the 1960s and 1970s. Fanzines originally contained commentary on original content, fan discussions, letter columns, and news, and later expanded their offerings to fan works like fan-created fiction and art (Coppa 2006). In the late 1980s and the early 1990s, fan communities moved online, bringing with them fan artworks and discussions. This migration to online platforms allowed fan communities to expand and to widely circulate an increasing number of fan works, but the ephemeral nature of online content posed challenges to their preservation.

[1.2] Fans adopted and created many platforms to host their works and fannish interactions, but they often ran into trouble as platforms sought to regulate or remove fan content. Blogging site LiveJournal suspended over five hundred accounts, many of them linked to fandom activity, in May 2007 ("Strikethough and Boldthrough," Fanlore wiki, https://fanlore.org/). A popular fan fiction archive, FanFiction.net (https://www.fanfiction.net/), deleted thousands of sexually explicit stories without warning in June 2012, citing their previously unenforced content policy prohibiting such content (Ellison 2012). These are just two notable examples from an extensive history of loss of online fandom content through restrictions and takedowns across many platforms ("Timeline of Major Fandom Purges, Restrictions, and Hassles Regarding Fanworks and Their Content," Fanlore). Fans can also lose access to content online when creators take their work down or when an online fandom archive shuts down.

[1.3] Fans have made great efforts to digitally preserve fan works themselves in archives like the Organization for Transformative Works' Archive of Our Own (AO3, https://archiveofourown.org/), founded in 2008, which on its website terms itself "a fan-created, fan-run, nonprofit, noncommercial archive for transformative fanworks, like fanfiction, fanart, fan videos, and podfic." Digital archives like AO3 allow for a more comprehensive collection of fan works with contributions from fans worldwide. These digital preservation efforts, driven in part by fans fearing the loss of more content from online platforms, help ensure long-term access to fan works and fan culture (De Kosnik 2016b).

[1.4] Most fandom preservation efforts target digital content, but several libraries and archives have acquired collections of physical objects. The Organization for Transformative Works (OTW) collaborates with the Special Collection Department at the University of Iowa to run the Fan Culture Preservation Project, which archives artifacts like fanzines and fandom memorabilia (https://opendoors.transformativeworks.org/fan-culture-preservation/). Most of the fanzines included in this collection date back to the era before fan interactions moved largely online, but fans today still create print copies of fan works, even those posted digitally.

[1.5] Fan binding—the practice of binding fan works, particularly fan fiction, into books—creates physical items that can aid in the long-term preservation of fandom culture. Although the practice of binding fan fiction into books is not new, its popularity grew significantly in 2020 with the creation of the Renegade Bindery Discord server by fan ArmoredSuperHeavy and their formation of Renegade Publishing with fellow fan binders in August 2020 (ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020a). The fan binders comprising Renegade Publishing and Renegade Bindery work independently to transform fan works into physical books. This practice creates unique collections of fan fiction that exist outside of the digital realm, where dangers like content takedown and loss remain a risk. Renegade Bindery provides an opportunity to study the practice of fan binding and how it affects fan works' preservation practices. Fan binding is a mode of expression of a larger trend outside of fandom that pushes back against corporate-controlled digital access models in favor of personal ownership and preservation.

2. Digital preservation of fan works

[2.1] Most fans today create, post, view, and circulate content digitally, such as uploading fan fiction to an online archive like AO3 or sharing fan art on a social media platform. Consequently, fans most often preserve these fan works in digital form, with varying success. Fans' turbulent history with loss of fan content on third-party platforms exemplifies the dangers of depending on platforms outside of fandom's control to preserve fan works. Fans have experienced restriction and loss of online content nearly as long as fan works have existed in that space ("Timeline of Major Fandom Purges," Fanlore). As recently as 2019, Yahoo! Groups, which had long hosted fan archives and discussions, shut down, removing content with little warning ("Yahoo! Groups Content Purge," Fanlore). As Abigail De Kosnik (2016b) warns, "For-profit corporate-owned sites have no commitment to the long term preservation of fans' cultural productions."

[2.2] Fan works posted on such platforms have no guarantee of long-term preservation and remain at risk of loss, making it clear that digital preservation efforts need to come from within fan communities. To that end, OTW maintains an infrastructure for preservation projects for fan works. AO3 hosts several different formats of fan works, including fiction, vids, and audio recordings. Through the Open Doors project, OTW runs preservation efforts "offering shelter to at-risk fannish content" (https://opendoors.transformativeworks.org/) like the GeoCities Rescue Project, which aims to preserve fan content after Yahoo's shutdown of GeoCities in October 2009 (https://opendoors.transformativeworks.org/en/geocities-rescue/).

[2.3] Fan works require digital preservation efforts because digital archives can more comprehensively store the vast amount of content fans continue to create. As a point of reference, AO3 reached seven million fan works archived on its platform in December 2020, and the rate of works being added to the archive continues to increase (OTW 2020). As part of the Open Doors project, AO3 also accepts imports from other online fan archives to securely preserve them. Open Doors and AO3 do not select which fan works to preserve or impose any content-related submission barriers, reflecting De Kosnik's (2016a) description of the fan archivist's mission: "to preserve all fanworks for all fans, not to judge which are 'worth' saving and which are not worthy." Fans' ongoing efforts in such digital preservation make such a comprehensive scope possible, but there are risks associated with digital-only archives.

[2.4] Most importantly, online content is inherently ephemeral. Digital collections on any platform may experience sudden, unexpected loss of content as a result of any number of factors, although fan fiction in particular has faced mass takedowns many times. Fan-directed preservation efforts historically achieve the best records of success, but they depend on fans' continued efforts because without them, as De Kosnik (2016b) notes, "fanworks will cease to be archived in a reliable way." Thus, even fan-made digital archives risk file loss. An example is the Audiofic Archive, which aimed to "preserve podfic files…and to provide stable access to those files in downloadable form" (jinjurly, n.d.). At its peak, the archive hosted about 25,000 podfics—that is, recordings of fan fiction read out loud. A server corruption caused massive file loss in 2016, and soon after, users could no longer add new podfics because there was insufficient server space ("Audiofic Archive," Fanlore). The creator of the archive seemingly abandoned the project, providing only sporadic, vague updates after 2016. Users can download the archive's remaining files but as of January 2022 still cannot upload any new podfics.

[2.5] In the case of preservation, "redundancy and tangibility are keys to long term survival" (ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020b). Archiving copies of fan works both online and in print makes successful preservation of these materials more likely in the long term. Of course, no physical archive could collect all of the works that fans create, but preserving fandom's physical objects is important. In addition to the necessary digital preservation of fan works, the activity of fan binding can preserve digitally posted content in physical form, creating a stronger possibility of long-term preservation.

3. Fan binding

[3.1] Fan binding transforms fan works like fan fiction, much of which exists only digitally, into physical books. To achieve this, many fan binders learn bookbinding. They purchase or make the necessary supplies, format the electronic files for printing, and bind the resulting printed pages into handcrafted books. Some fan binders prefer to format and design the interior and cover electronic files, then print the book using third-party print-on-demand vendors. The practice of fan binding existed long before its recent increase in practice and visibility, but information about and scholarship on this topic are limited, likely partly as a result of the lack of a dedicated fan binding community before 2020, making fan binding less visible. Even when it occurred to fans to print and bind digitally posted fan fiction, no dedicated place existed to ask other fans about methodology or best practices.

[3.2] The scattered examples of online discussion regarding printed fan fiction reflect fans' general uncertainty in approaching the practice. In 2014, a Reddit user wanted to have copies of favorite fics printed as books for personal use but was unsure of the "legal/'etiquette' issues" of doing so (perdur 2014). Similarly, a user on Quora submitted the question, "Can fanfiction be bound into a book for my own personal use?" To both posts, replies answered in the affirmative; indeed, many responders indicated that they had bound or printed fan fiction themselves. The replies also offered basic instructions and tips for turning fan fiction into physical books, either by binding or by having the fan fiction printed by a print-on-demand vendor.

[3.3] These fans did not have a community online dedicated to the practice of fan binding, so they worked individually or in small groups on projects. The formation of the fan binding community Renegade Bindery in 2020 gave fan binders a place to exchange tips and ideas to apply to their projects; it also created new opportunities for fans unfamiliar with the practice to discover and take up fan binding themselves. Though only a few years old, this established community of fan binders provides a way to study identifiable trends regarding why fans started fan binding, how they bind fan works, and how the practice could contribute to fan work preservation efforts.

4. Methodology

[4.1] To gain a better understanding of fan binding as a practice as well as fan binders' motivations and methods, I conducted informal interviews and conversations with a group of fan binders on the Renegade Bindery Discord server through a combination of text and voice chat. In December 2020, the moderator of the Discord server, ArmoredSuperHeavy, introduced my research topic to the community, and any member who expressed interest in participating was added to a private channel dedicated to these discussions. The Discord server only allows members over eighteen years old to join, so all participants were eighteen or older. In total, twenty-three members joined the private channel, and twelve provided responses.

[4.2] On December 23, 2020, I posted a set of discussion questions in the private channel and emphasized that anyone who chose to respond could address any of the prompts they chose, and answering all of them was not necessary. During the following week, participants responded in the private Discord channel or in a direct message with me via text or voice chat, whichever they felt more comfortable with. I reviewed all of the responses and identified trends and outliers, as reported in the next section. Responses from participants are included here in the form of general statements of identified trends, paraphrasing, and direct quotations. Responses are sourced with the prefix FB- followed by the participant's chosen name or, if anonymous, an assigned number, according to participant preference. No personally identifying information was obtained from participants aside from preferred pronouns. Participants had the opportunity before publication to ensure their contributions were accurately represented.

5. Renegade Bindery

[5.1] The surge of interest in fan binding can be attributed to ArmoredSuperHeavy and the creation of Renegade Bindery. ArmoredSuperHeavy started their attempts at transforming fan fiction into books in the early 2000s through a copy shop, but they learned bookbinding in 2018 so they could more accurately capture the look and feel of a book (ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020b). They wrote up detailed instructions in an undated document entitled "How to Make a Book from an AO3 Page" and shared it freely online. The document provides enough information on fan binding to get anyone interested in the process started. It includes a list of materials needed, how to acquire them, and step-by-step guidelines for formatting files for printing and bookbinding. The document gained the attention and support of online communities, encouraging people interested in the practice to take up fan binding themselves. In June 2020, ArmoredSuperHeavy created a Discord server for everyone who had expressed interest in fan binding to provide a place to share projects, methodology, and general discussions (FB-ArmoredSuperHeavy).

[5.2] After the Discord server's surge of new members and active fan binders, Renegade Publishing, a public-facing subset of the Discord server, was formed in August 2020 (ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020a). These fan binders, and anyone else who requested to join, set up individual imprints under Renegade Publishing. In addition to the Discord server, called Renegade Bindery since August 2020, Renegade Publishing has a Tumblr page stating their purpose, listing their members, and welcoming new participants:

[5.3] Renegade Publishing is a not-for-profit guild of artists engaged in fanbinding—publishing in extremely limited edition fannish works, including fanfiction, meta, original fic, zines and other works. Most works are made in handmade editions of one or two copies. Members work self-directed, selecting works to bind individually, and may or may not offer commissions for binding services. We consider publishing to be a political act of resistance and self-determination, that makes an unequivocal statement about the value we see in these endangered, underground works. We refer to our work as fanbinding. (Renegade Publishing, n.d., b)

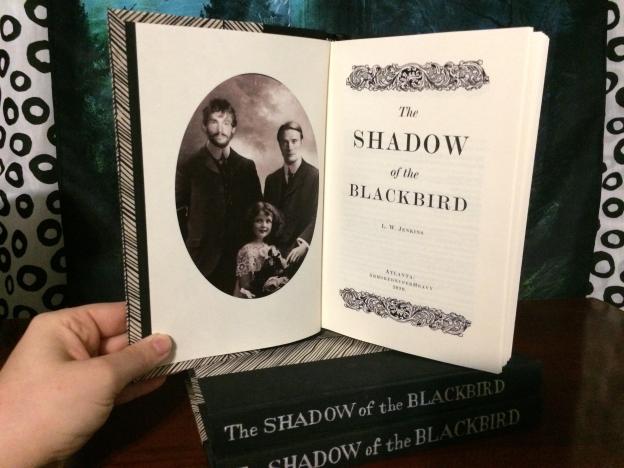

[5.4] The Renegade Binding group maintains the Tumblr page, also officially established on August 17, 2020 (Renegade Publishing, n.d., b). Fan binders in Renegade Publishing post pictures of their work to the Tumblr page, which includes fan fiction bound by hand (figure 1) or designed by a fan binder and printed by a print-on-demand vendor.

Figure 1. Frontispiece and title page of a completed book bound by ArmoredSuperHeavy of the fan fiction "The Shadow of the Blackbird" by L & Deadly, completed June 27, 2020 (https://ArmoredSuperHeavy.tumblr.com/post/622113437337698304).

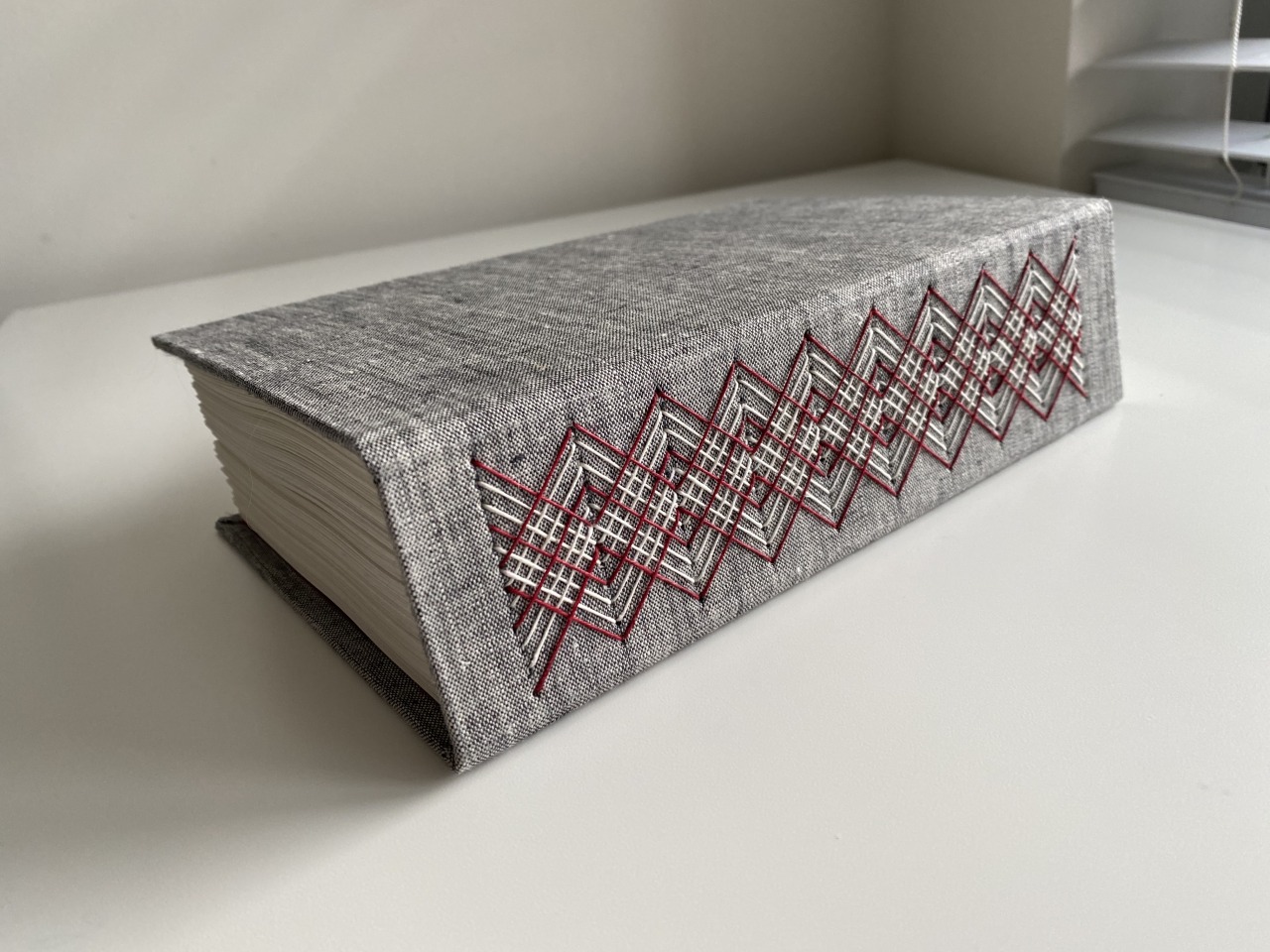

[5.5] ArmoredSuperHeavy matched the style of the book to the story: a fan fiction set in the nineteenth century based on the TV show Hannibal (2013–15). The text, print ornaments, and design of chapter headings all reference the style of that time period (FB-ArmoredSuperHeavy). Another fan binder uses different glueless bookbinding techniques, including Coptic stitch and long stitch bindings, to create decorative designs (figure 2).

Figure 2. Completed book bound through a variation on long stitch binding by queercore_curriculum of the fan fiction "Away Childish Things" by lettered, completed December 12, 2020 (https://queercore-curriculum.tumblr.com/post/637322080975798272/away-childish-things-by-letteredlettered-look).

[5.6] As of January 2022, Renegade Publishing has thirty-three imprints, and the Renegade Bindery Discord server has over 455 members of varying experience (Renegade Publishing, n.d., b). Although many fan binders are new to binding, several have been binding fan fiction and other works for years but previously lacked a community to participate in. Before discovering and joining Renegade Bindery, a few fan binders came to the practice from bookbinding, and one fan binder even first joined a general bookbinding community with the intention of binding fan fiction (FB-HL). One fan binder commented on the new opportunities of having a community: "I am very happy that there's now a clear source of information for the process from start to finish—when I wanted to get into binding my own texts I found few resources to do so" (FB-simply-sithel). The Discord server provides fan binders and their community with a centralized place to find and share resources, tips, and fan binding projects.

6. Fan binding motivations

[6.1] Before creating the Discord server, ArmoredSuperHeavy posted "Why I Am a Guerilla Publisher" (2020d) on their Tumblr and Dreamwidth blogs. The post lists some of their motivations for fan binding, which includes establishing the validity of fan fiction as a genre with stories that deserve to printed and preserved:

[6.2] My long-term goal is to capture and preserve in print a broad array of fic and outlaw writing. Therefore, I haven't leveled up my equipment to "fine binding" levels, I economize as much as possible the decorative paper, and don't lavish hours on technical perfection. To me it is a race against time to bind as many works as I can. I am racing against repressive bans of adult content, the chilling force of contemporary purity policing, and my own mortality.

[6.3] In the spirit of preserving fan culture, ArmoredSuperHeavy also emphasizes their dedication to the continuation of a fandom gift culture over commercialization when creating bound fan fiction. The fandom gift culture refers to the common practice in fandom of prioritizing freely accessible fan work content with nonmonetary reciprocation (Hellekson 2009). Such reciprocation can take the form of commenting on the fan work or creating more content for the fan community. It serves as a form of appreciation to the fan work creator and also helps constitute the larger fandom community. In this vein, many fan binders, including ArmoredSuperHeavy, bind two copies of each fan fiction: one for their collection and the other as a gift to the author (ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020c). One fan binder stated that his primary motivation was to provide fan fiction authors with recognition and support by giving them a bound book of their work, thus giving them something back for all their efforts in freely providing their work to fandom (FB-HL). Some fan binders in Renegade Publishing do take commissions, but most do not, for reasons such as a desire to personally choose which fan fictions to bind, uncertainty about pricing, or often out of a preference to maintain a fannishly understood gift culture over a seller-customer relationship (Renegade Publishing, n.d., a; ArmoredSuperHeavy 2020c).

[6.4] The rest of the fan binders at Renegade Bindery started fan binding for many different reasons; many started for the first time in 2020. Often newcomers stumbled on ArmoredSuperHeavy's bookbinding document or one of their posts and were interested in learning more. For some, being forced to stay inside during the Covid-19 pandemic was a driving factor to getting started. One fan binder noted, "I was very eager to not only find a community but a hobby to keep me busy (and sane) in my time off" (FB-Goose Island). Another new fan binder, a fic writer, picked up the practice after ArmoredSuperHeavy reached out to him about binding one of his fan fictions, and he became interested in trying it himself (FB-Wolffe). A couple of binders came to the practice because they were interested in binding other types of works, like a family cookbook, narrative role-play threads, or gaming transcripts, then started binding fan fiction as well (FB-1, FB-kqlink, FB-simply-sithel).

[6.5] Several fan binders cited their desire to house fan fiction in the beautifully bound books usually reserved for traditionally published works. Fan binders are people who love fan fiction and see it as inherently valuable; many outside of fandom would disagree. Some fan binders thus expressed satisfaction in making the stories they loved into a book as beautiful as a special edition of a celebrated classic novel. As one fan binder explained it:

[6.6] Metaphorically, we judge books by their covers all the time. If a book is a mass-market paperback on a gas station rack, then we assume out of hand that the insides are shitty—probably some gross, iddy romance that the reader is ashamed to be seen reading. On the other hand, if you see a leather-bound, gold-tooled book on someone's shelves, you assume it's A Classic:TM:. Something valuable. Fic is derided and ignored by the mainstream, held in similar regard to gas station paperbacks. There's a satisfying twist of irony in binding the type of book that people like Jay Gatsby or my grandparents would buy—something that conveys prestige and class consciousness—but is socially marginal on the inside. (FB-Wolffe)

[6.7] As preservation objects, these books preserve both the stories and validity of fan fiction as a genre. Putting the stories into handcrafted works of art indicates the value the artist placed in it; fan binding preserves this perception of fan fiction. Further, people identifying as LGBTQIA+ make up a large percentage of fandom communities (Dym and Fiesler 2018); unsurprisingly, the fan fiction they create frequently depicts queer characters and content, which has always resulted in a higher risk of censorship and takedown online. As ArmoredSuperHeavy (2020b) notes, "Queer and sex-positive art is forever on unsteady ground, be it from lack of financial resources, conservative social media terms of service, or respectability politics leading to self-censorship." Binding these stories pushes back against that marginalization, offering "a way for queer communities to challenge capitalist production" (FB-SleepingPatterns). Fan binding not only protects fan fiction and marginalized communities from erasure but also wraps these stories into a binding they would not receive through traditional publishing.

[6.8] For most fan binders, the reasoning behind learning to bind is a personal one: the desire to learn a new craft or to create a physical copy of a beloved fan fiction to put on a bookshelf next to favorite books. Fan binders acknowledge the role that their efforts could play in long-term preservation of fan fiction, but more central to their motivation is preserving the fan fiction for themselves and for the fans who love these stories right now. Fan binding results in a copy of a fan fiction that cannot suddenly disappear from an online platform or be lost if a hard drive or server fails. For most fan binders, the choice of why and how to preserve fan fiction is personal; it is a way to preserve stories that are important to them. The fan fiction they choose to bind reflects this.

7. Choosing texts to bind

[7.1] Discussions with fan binders indicated that in general, several criteria are considered when choosing which fan text to bind. First, fan binders tend to choose fan fictions that have personal meaning to them. As one fan binder wrote, "I've just been playing favorites" (FB-1). They simply enjoyed reading it; it had a memorable story that stuck with them, or they read it at a specific time in their life and wanted to "preserve memories as much as the stories themselves" (FB-Wolffe). Second, fan binders value binding works most at risk of loss, either because of their format or content. For example, one fan binder identified podcasts as "particularly ephemeral" and focuses on binding podcast transcripts, which provides podcast fan communities with an alternative method of access to the primary text (FB-kqlink). Fandoms based on podcasts like The Magnus Archives (2016–21) rely on the source material's always being readily available, but those original-source audio files could easily disappear—in this example, particularly because the podcast ended in 2021. Some podcast archives currently exist, such as the PodcastRE project (https://podcastre.org/), but they can only preserve a small percentage of existing podcasts (Morris, Hansen, and Hoyt 2019). Without that source material, the fan fiction based on it would lose context, and creation of new fan works would inevitably slow.

[7.2] Relatedly, in terms of mitigating the risk of loss, the content of a fan artwork, particularly those that contain themes like incest or include explicit violence, may place it at higher risk of takedown, so fan binders may prioritize creating a physical copy. Pushback against such "problematic" content in fan works does not only come from outside parties. Fans themselves—or, as Joseph Brennan (2014, 364) describes it, "conservative factions of online fandom"—sometimes respond negatively to what they deem unacceptable content in fan works, especially those that draw a lot of attention. Fan creators tag their work with content warnings and keywords as standard practice, to reduce the chance that readers will experience a story upsetting to them (Schaffner 2009). One tag for works with possibly upsetting content is "Dead Dove: Do Not Eat," which references a meme of a character from Arrested Development (2003–19) who looks into a bag labeled "Dead Dove: Do Not Eat" and says in response, "I don't know what I expected" ("Dead Dove: Do Not Eat," Fanlore). The "dead dove" tag warns readers that the fan fiction will contain exactly what the author stated—usually content that some readers may prefer to avoid—and not to expect otherwise. Even so, such works often encounter criticism both in and out of fandom. ArmoredSuperHeavy (2020b) notes, "The more under attack a work or author is, the more interested I am in binding it." Likely to reflect this preference, ArmoredSuperHeavy (n.d., a) named their imprint in Renegade Publishing "Dead Dove Publishing."

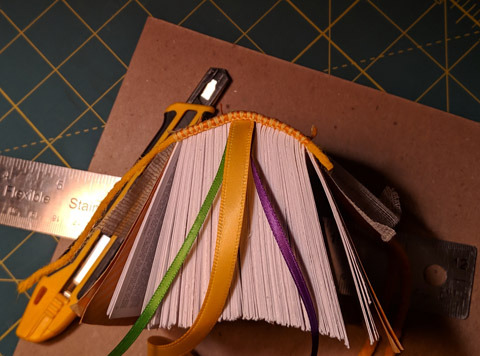

[7.3] Although these are the most common ways to choose which texts to bind, they are certainly not the only factors to consider. One fan binder has a particular interest in binding "fics that inspired a lot of interaction," which they see as central to fandom (FB-kqlink). Another selects fics seen as a "fandom/cultural icon" or something a friend would appreciate as a gift (FB-Wolffe). Some fan binders double as fan fiction authors and begin by binding their own works (figure 3).

Figure 3. An in-progress book bound by simply-sithel, posted February 8, 2019 (https://simply-sithel.tumblr.com/post/182673172959/am-trying-to-think-if-theres-any-part-of-crafting).

[7.4] No matter the motivation behind it, fan binders create unique collections of fan fiction that preserve these works as physical objects, whether they remain permanently in personal collections or end up preserved in an archive.

8. Preserving fan fiction through fan binding

[8.1] Physically or even digitally, preserving all that fandom encompasses as an experience and as a culture would be impossible. Bound fan fiction can preserve the stories but not the source material, and especially not the general fandom conversation the fan fiction took part in. At its core, fandom is a conversation—and sometimes an inside joke—that spans platforms and generations; it requires a certain level of immersion to fully understand. Fan fiction authors frequently make use of readers' knowledge of the source material as a storytelling mechanism. When a recognizably villainous character from a television show appears in a fan fiction, the author expects the readers to know that character's background and to pick up on clues to the villain's role in the story according to that knowledge. The context for a fan fiction might come from outside the source material in the form of social media posts or a popular fan comic. Without the source material and the fandom interactions that led to the fic's creation, readers cannot understand the full breadth of meaning held within the story—and that does not even take into account fan fiction genres like crossovers, or knowledge of common fic tropes, or well-known concepts that are unique to each fandom. "Reading and writing fanfiction is a very, very personal experience," one fan binder wrote, "one that has limited meaning out of context" (FB-queercore_curriculum). Preservation efforts, both physical and digital, will inevitably leave out some part of the fandom experience. Yet even knowing that some of the context will be lost, fan fiction deserves a place in archival collections of fan works, both for the fans who love these stories now and as an enduring piece of fandom history.

[8.2] Although long-term preservation is not the primary motivation for the majority of fan binders, most do take it into consideration and incorporate it into their practices. Loss of context certainly remains a barrier to long-term preservation of fan fiction, but it is one that fan binders are aware of and are actively seeking solutions to, as my example of fan-created podcast transcriptions shows. To address the reality that the source material itself might not remain as readily available and well known as it is now, fan binders may include some contextual information, like a synopsis of the plot or a cast of characters, in a preface; one fan binder included further information on "when and in what climate it was written" in a foreword (FB-2). Bound fan fiction also lacks the online-inflected interactive aspect of fandom, such as threaded comments, hashtags, categories, or author notes, all of which are important in fandom culture. In response, some fan binders make it a point to include any author notes as well as fan art inspired by the fan fiction. As one fan binder pointed out, "If you include fanart as illustrations, you will have preserved two types of fan creation side by side, within another form of fan creation" (FB-katethereader). These efforts provide context and snippets of fandom culture that might not be readily available to readers of future generations and make bound fan fiction more useful as a preservation object.

[8.3] Any collection of bound fan fiction can have only a limited scope. Considering the vast quantity of fan fiction published online, "even all the fanbound fics in the world put together would only scratch the surface of the amount of published fic in a single medium size fandom" (FB-HL). In addition, as several fan binders pointed out, the time and expense required for bookbinding limits how many works of fan fiction can realistically be preserved in this way (FB-Goose Island, FB-ArmoredSuperHeavy). According to a few fan binders' estimations, binding a book takes anywhere from six hours to a few days, and the cost of production ranges from $20 to $100, depending on material quality and story length (FB-ArmoredSuperHeavy, FB-SleepingPatterns). Even if fan binders could somehow bind every fan fiction in existence, no archive could hold a collection of such scale. That said, binding on such a large scale would contribute little to the existing framework of fan work preservation because digital archives already comprehensively collect fan works. What fan binding can do is make a long-lasting statement about the validity of fan fiction as a genre that should be preserved and give these stories, chosen as they are by fans, a better chance of surviving in the long term, even if those digital archives shut down.

[8.4] Fan binding is unlike traditional preservation efforts because most fan binders do not view their work as primarily an archival effort. They appreciate the contribution their work could have in long-term preservation efforts and plan for that eventuality, but they prioritize preserving the stories for themselves for the duration of their lifetimes, often because they fear content loss. According to one fan binder, "There is a very good chance some of my favorite stories will disappear in my lifetime and that is unacceptable" (FB-kqlink).

[8.5] Preservation of fan fiction does not necessarily equate to inclusion in an archive for future generations, although doubtless fan binders will donate collections of their work to libraries for long-term storage of both the stories' text and the uniquely handcrafted books that house them. The people who will appreciate these fan fictions the most read them right now; they are immersed in current fandom culture, and these stories hold personal meaning. Yet losing a favorite fan fiction would be devastating, so if fans take up fan binding as a way to preserve beloved stories on their bookshelves for the duration of their lives, then I would argue that this practice may be understood as a preservation effort. Even unintentionally, these bound fan fictions give fans more stable access to their favorite stories. Mizunocaitlin (n.d.), for example, a fan on Tumblr, recounted how a favorite Star Wars fic disappeared from the internet. As a result of a combination of an archive shutdown and incompatible file formats, that fan fiction now exists nowhere online. Years before, though, mizunocaitlin had printed out the fan fiction and put it into a binder, which now likely holds the only surviving copy. These fan-created books—whether created informally from three-hole-punched printouts in binders, comb bound at a copy shop, designed and submitted to a print-on-demand vendor, or printed out and then painstakingly sewn and bound between covers—may not circulate widely the way digital fan fiction does; nor can they capture the same breadth of fandom content as digital archives do. In the long term, though, when the digital records have become obsolete or have been removed, some of these books will still exist. As one fan binder theorized, "In the archival sense of the word, on the hundreds of years timescale, I think fan binding is the only way the fics will survive" (FB-HL).

9. Undigitizing trends

[9.1] Although most fandom interaction and content circulation currently occurs online, fan binding is just one of many types of fan activity with a material aspect. Fan creators make jewelry and outfits for cosplay, prints and stickers of fan art, and mimetic crafts like prop replicas (Jones 2014; Scott 2015; Hills 2014). Although fandom can be experienced solely digitally through fan creations like fic posted in online archives, art circulated on social media accounts, and discussions hosted on online platforms, the desire for fan-related, fan-created physical items remains. Fan binding purposefully transforms a fan work posted freely online into a physical item; this activity requires an investment of time, money, and effort to create and preserve.

[9.2] It is perhaps unconventional to preserve content posted digitally by transforming it into physical objects, but if fan fiction only followed traditional methods of publishing and preservation, it would not exist at all. One fan binder described this practice as undigitizing: "There's a lot of push to digitize and store your pictures and documents and all that jazz, so that you have fewer physical objects that you have to keep track of. But with fanbinding, we're un-digitizing literature that was designed to be consumed on a computer and making physical libraries out of things that used to be digital only" (FB-1).

[9.3] This recent trend of undigitizing, or creating and collecting content produced digitally in a physical format, also exists outside of strictly fandom communities and fan practice, most notably in the world of vinyl record collection. Such collections have seen a 40 percent increase in year-over-year sales growth even as streaming music platforms provide a seemingly more efficient and cost-effective option (Wohlfeil 2019). Research provides some possible reasons for this trend, including an attempt to "disrupt the music industry's efforts to define and regulate their consumer identities" (Hayes 2006, 52) and regain "the feeling of being again in full control of use and ownership" (Wohlfeil 2019, 2), which parallel many fan binders' motivations. Thanks to the undigitizing trend in the recording industry, even modern albums exist in vinyl format—a practice not dissimilar to binding digitally posted fan fiction into handcrafted books. Indeed, Markus Wohlfeil, echoing the concerns of some fan binders, reports that many vinyl collectors do so out of a fear of content loss in digital libraries, citing Apple's shutdown of iTunes, which resulted in the loss of users' entire digital music libraries, and points to vinyl collecting as a "dependable, reliable, and trusted music format that offers independence and full control" (2019, 2). Like most fan binders, these modern vinyl collectors do not necessarily seek out vinyl music as a way to preserve the songs in the long term. Instead, it is a way to preserve their personal access without reliance on digital platforms controlled by third parties.

10. Implications for archival collections of fan works

[10.1] Physical collections of fan works exist in some libraries and archives today, most of texts like fanzines from the era before the internet. The Special Collections & University Archives at the University of California, Riverside, holds over 75,000 fanzines and continues to accept donations from fans (https://library.ucr.edu/collections/fanzines-collection). The University of Liverpool library holds in its science fiction collection a number of fanzines (https://libguides.liverpool.ac.uk/library/sca/sfjournals). The Special Collections and Archives at the University of Iowa libraries (https://www.lib.uiowa.edu/sc/) partners with OTW to archive fan works as part of the Fan Culture Preservation Project. The scope of the Fan Culture Preservation Project includes "fan artifacts such as letterzines, fanzines, and other non-digital fanworks and memorabilia" (https://opendoors.transformativeworks.org/fan-culture-preservation/). Other fanzine and fan work archive collections may not have so broad a scope, but this could change as fan binding becomes more popular and recognizable.

[10.2] If the practice of fan binding continues to draw more fans' attention and participation, there could be hundreds of unique collections of bound fan fiction in a few years' time. ArmoredSuperHeavy's collection includes more than two hundred volumes as of 2022. Even if fan binders' desire for preservation extends only to personally having a copy that cannot suddenly disappear from an online platform, their bound works will likely exist beyond their lifetimes. Many fan binders have already considered this fact and upon their deaths plan to leave their collections to an archive or library that will accept them.

[10.3] Some fan binders expressed reservations about including their bound fan fiction in an archival collection. A few were hesitant to give their books to an archivist who may not have the same appreciation for fan fiction as fans would. An archive unconnected to fandom may view bound volumes of fan fiction simply as art objects rather than stories to be enjoyed, and fan binders would prefer their collections end up in a place that "understands the value of the collection" (FB-Wolffe, FB-Aliya Regatti). As one fan binder wrote, "I'm a little skeptical that someone will find the fics I've bound in an archive somewhere down the line and actually sit down and read them" (FB-queercore_curriculum). Others were not sure whether a library or archive would accept the books and hesitated to inquire. A few expressed concerns over the legal and ethical implications of donation. Fandom has a long and complicated history with copyright infringement allegations, one that still affects fans' willingness to bring attention to their works. Even some fan binders who do not take commissions and therefore do not profit from their work remain wary of possible repercussions from copyright holders (FB-1).

[10.4] Fan binders may also feel uncomfortable donating bound fan fiction to an archive without the permission of the author; as one fan binder said, "I'm not the one who wrote it, so I wouldn't want to put it up for access somewhere the author never intended" (FB-1). Fans have long prioritized privacy, with fandom pseudonyms or usernames curated separately from their real-life identity, and many continue to do so (Dym and Fiesler 2018). That culture has begun to shift as fandom has gained increasingly mainstream popularity and visibility, resulting in "the opening of fandom culture" (FB-SleepingPatterns). Archivists handling fanzine collections face similar dilemmas, particularly when considering fanzine digitization, which would introduce them to a wider audience that the fanzine authors did not anticipate at the time they were writing. Archivist Melissa Conway has emphasized the importance of consulting with fans on fanzine preservation and dissemination decisions, even suggesting that catalogers familiar with fandom be hired for that purpose (quoted in Lee 2011). Ideally, archival collections already accepting fan content like fanzines and fandom memorabilia would expand their scope to include bound fan fiction and would take these considerations into account.

11. Conclusion

[11.1] The practice of preserving physical copies of contemporary fan fiction existed in the years between fandom's migration online in the early 1990s and the creation of Renegade Bindery in 2020, but documentation of such projects remains infrequent and scattered. Fans tend to focus primarily on digital preservation, which takes priority because most fan fiction is posted digitally; digital archives can comprehensively preserve fan content, while physical archives must curate collections. As with any preservation effort, redundancy in fan work preservation can only benefit attempts to preserve fandom content. Fan binding provides a method of creating and preserving digitally created fan fiction as physical objects. More broadly, fan binding as a practice parallels other kinds of personal preservation efforts that exist outside of fandom and that push back against solely digital methods of content access and ownership as a way of regaining control of personal collections.

[11.2] Within fandom, fan binding hearkens back to the fanzine-based circulation of texts that characterized certain preinternet fandoms; indeed, those fanzines appear more frequently in archival collections every year. Fans today create and circulate more content than ever, and to accurately represent modern fan culture, fan work archives must expand their scope to accept works created after fandom's migration online. Although fan binders generally do not create bound fan fiction solely for long-term preservation purposes, they do recognize their books' value as objects of preservation, both for the stories themselves and as a lasting statement about the validity of fan fiction as a genre. The books also exist as physical objects, worthy of collection on that basis alone.

[11.3] We live in a time where digital storage is practically limitless, allowing us to access, stream, and preserve vast quantities of data. Yet the things we choose to preserve in a physical format gain new meanings that express their inherent value while acting as a statement of identity. Instead of choosing to more cheaply and efficiently access digital content, these creators and collectors put in the effort to own a physical copy. Fan binding, along with other forms of physical collection, places value in items by virtue of someone's choosing to own something that takes up space in a personal collection. The existence of these fan-bound collections provides long-term access to fan content and acknowledges the importance of fan works and fan culture, establishing fan binding's important role within existing fan work preservation efforts.

12. Acknowledgments

[12.1] Many thanks to ArmoredSuperHeavy and the Renegade Bindery fan binders who participated in these interviews for their insightful and detailed responses, and to all Renegade Bindery members for being such a welcoming and supportive community.