1. Introduction

[1.1] It only takes one video to fall down a YouTube rabbit hole. I clicked on one video, a fan-made documentary detailing the history of the esports organization Team SoloMid, and set off an algorithmic feedback loop that introduced me to the world of fan-made video game history documentaries. In these videos, fan-historians carefully trace and narrate the evolution of video games and their communities in an engaging audiovisual format. The algorithm had a veritable treasure trove of such videos to recommend to me, a fan of the popular multiplayer online battle arena game League of Legends (Riot Games, 2009): deep dives into the design and development of popular characters; detailed biographies of professional players and live streamers; and play-by-play retellings of high-stakes competitive matches. These videos, helpfully served up one after another by YouTube's video recommendation algorithm, taught me the history of my fan community.

[1.2] As I watched, it quickly became clear that these documentaries covered a very specific mode of League of Legends fandom. The histories tell the story of a community of mainly White and Asian young men who express their fandom through hypercompetitive game play. A more systematic analysis of the videos produced by the four most popular League of Legends documentary channels reinforced my initial observations. I carefully watched the top five most-viewed videos on each channel, looking to see whose faces were visible in the game play footage that made up the bulk of their visual content. Virtually all these videos featured only White or Asian men, with a noticeable bias toward the inclusion of esports athletes and professional live streamers. Three of the twenty videos, however, did feature women. Two of the three videos covered what they called "failed experiments" of all-female professional teams and reinforced the narrative that women, for whatever reason, were just not good at playing the game. The third focused on voice actors for League of Legends characters, with female voice actors positioned not as players or fans but as outsiders to the fan community. The appearance of women in these three videos did little to correct the impression that League of Legends fans are, by and large, men.

[1.3] If, as Lori Morimoto and Bertha Chin (2017) argue, fandoms are imagined communities that cohere through the circulation of common discourses and practices among disparate individuals, the League of Legends fandom imagined by these fan-made documentaries has no place for a woman of color like me. Rather, these imaginings are patterned after what Janice Fron et al. (2007) call the "hegemony of play." These scholars argue that the "power elite of the game industry is a predominately white, and secondarily Asian, male-dominated corporate and creative elite" that creates games for "self-selected hardcore 'gamers,' who have systematically developed a rhetoric of play that is exclusionary, if not entirely alienating to 'minority players'" like women, BIPOC people, and queer folks (1). Crucially, the hegemony of play implicates a wide variety of actors in the creation and perpetuation of exclusionary rhetorics of play. The biases and bigotries of individuals matter but so do the hiring practices, business strategies, and technologies of the video game industry. Social media platforms heavily used by video game fans, like YouTube and Twitch.tv, also have a hand in creating and reinforcing the hegemony of play. Opaque methods for blocking abusive viewers on Twitch, for example, make it more difficult for marginalized people to feel comfortable participating in gaming and live streaming communities (Gray 2020; Woodhouse 2021). The technologies that power video game fandom work alongside biased players and industrial practices to "perpetuate a particular set of values and norms concerning games and game play, which tend to subordinate and ghettoize minority players and play styles" (Fron et al. 2007, 2).

[1.4] Here, I consider how the technologies that facilitate fan culture are implicated in the creation and circulation of narratives that reinforce exclusionary systems like the hegemony of play. Using League of Legends fan documentaries as a case study, I argue that the algorithms that organize, sort through, and promote content on popular web platforms like YouTube play a significant role in shaping the narratives that fans, scholars, and others tell about fan communities. I make this argument by exploring how League of Legends fans use YouTube as an archive as they research, narrate, and visually depict the history of their fandom. Through an analysis of how YouTube's algorithmic curation of this digital archive promotes game play footage created by White and Asian men while obscuring the contributions of BIPOC players, I show that the possibilities for how fans can audiovisually imagine their fan communities are limited. The imperatives of YouTube's video search and recommendation algorithms favor the hegemony of play and in doing so render BIPOC players, queer players, disabled players, and others invisible in the archive that fans use to write the history of their community. Working at the intersections of critical archive studies, critical algorithm studies, and critical race studies, I aim to highlight both the potential and the pitfalls of deploying popular media sharing platforms like YouTube, Instagram, Tik Tok, Soundcloud, and Wattpad as archives with which to preserve, study, and write fandom histories.

2. History, archives, and fandom

[2.1] As the proliferation of media products promising to tell fans the real history of their favored texts and objects suggests, media fans care about media history. While products like fan magazines, DVD extras, and tell-all books play upon fans' nostalgia and position them as consumers of industry-produced histories (Hunt 2011), fans are also active participants in recording, preserving, writing, and interpreting history and historical narratives. We have already seen, in the example of League of Legends fan documentaries, that fans write historical narratives about both their fan objects and their own communities. However, as Nick Webber and E. Charlotte Stevens (2019) argue, it can be difficult to identify when fans are doing the careful work of information collection, organization, contextualization, and interpretation that makes up the process of producing history. A list of events in a blog post, for example, is not exactly a work of history, even if it may later be of use to a historian. Keeping this consideration in mind, I work here with a rather expansive view of who is involved in the making of history. Michel-Rolph Trouillot (1995) reminds us that "the overlap between history as social process and history as knowledge is fluid" (26) and emphasizes that historians are not the only people who work to produce history; those who make sources that will one day be used in a historical monograph, for example, are as implicated in the crafting of history as the historian who does the writing.

[2.2] Given this broad understanding, we can see fans involved in producing history at many stages. The "citizen-fan journalists" who stealthily snap photos of film sets in order to report on media productions (Hills 2015) and the female fans who recorded their responses to popular media in fan letters (Bielby, Harrington, and Bielby 1999; Ford 2008; Neuhaus 2009), for instance, create the sources that help shape the narratives of media history that are possible to tell in the future. Collecting, preserving, and archiving media and fan materials are popular fan activities that also contribute directly to the production of history. Lincoln Geraghty (2014) argues that fans are often motivated to collect by a desire to preserve or recreate a nostalgic past; collecting, cataloging, and carefully displaying merchandise and memorabilia might be considered an attempt to narrate history through objects rather than words. Fan collections may even become instrumental in institutional efforts to preserve history, as fans' private collections may have ephemera that had long been considered too insignificant to save (Andon 2013; Mora-Cantallops and Bergillos 2018). Fans also preserve their own cultural production by publishing it, with digital archives like Archive of Our Own (AO3) turning fan fiction publication into a practice of archiving (Knight 2018). While these preservation efforts may be incidental to the acts of collecting toys or sharing fan fiction with friends, fans also intentionally preserve history. Pop music fans, for example, have done a great deal of work to save, catalog, and maintain materials that may be seen as too low-brow, superfluous, or unimportant for institutional archives and museums to care about (Baker 2015). Jez Collins and Oliver Carter (2015) call these fans "activist archivists," arguing that they push back against institutional biases in the selection of which cultural texts are saved.

[2.3] Many fan studies scholars have similarly considered the subversive and progressive potential of fan-created archives. Archives sit at the heart of many digital media fandoms, and the ways that fan archives are organized and operated reveal how fan-archivists and archive users envision their communities. Both Abigail De Kosnik (2016) and Alexis Lothian (2012) build upon Jacques Derrida's (1995) theorization of the archive to explore fandoms as archival cultures. De Kosnik sees fan fiction archives as a sign of an important shift of power in media culture as consumers, especially those who have historically been marginalized within media industries and memory institutions, have seized the ability to save their media works and choose how and where their productions are preserved. This shift is the result of media consumers becoming the "archons" who, according to Derrida (1995), protect archival material, determine what gets saved and what does not, and, crucially, "have the power to interpret the archives" (10). Lothian (2012) similarly identifies the importance of fans acting as archive creators and curators but recognizes that fan archives and the communities that cohere around them are, like all communities and archives, "constituted through violence and erasure" (548). There must be exclusions from the community and from the archive since, as Derrida argues, there is "no archive without outside" (1995, 14).

[2.4] Despite the salience of this point, much of the work on fan archives emphasizes their radical openness and inclusivity. This is not surprising, as the archives under study tend to be extremely open and easy to use. From the purposefully inclusive AO3 to participatory and interactive fan wikis, fan archives are characteristically accessible. Yet they are also spaces of struggle and negotiation over what can and should be saved. As archons, the fans who construct, curate, and contribute to fan archives have the power to decide that certain materials, and the people who created those materials, should not be represented in an archive. Fan wikis for Battlestar Galactica and Lost, for example, exclude information about noncanon queer ships despite including other kinds of noncanon information, resulting in the marginalization of fans who engage in and express themselves through queer shipping in those fan communities (Toton 2008; Mittell 2009). The inclusion of certain materials can also exclude groups of fans, as is made clear in current debates around the tolerance of racist fan works on AO3 and the archive's attitude toward (not) protecting fans of color (Stitch 2020). The choices made by archons have ramifications beyond just which documents get saved and which do not. Such decisions make clear to certain groups of fans whether they will be welcomed in a community.

[2.5] The decisions of archons also have ramifications for who can and cannot be represented when fan archives are deployed as sources of historical evidence. Scholarly works on fandom history mine institutional and fan-created archives of fan works to access communities that are no longer living (Bielby, Harrington, and Bielby 1999; Ford 2008; Neuhaus 2009; Lanckman 2020), making representation in fan archives a question of historical representation. Fan-archons help determine what stories are told and valued: as Melanie Swalwell, Helen Stuckey, and Angela Ndalianis (2017) argue of video game fans, "fans have been significant actors not only in documenting the history of games, but in constructing what is valued, historically" (7). Considering the creation and curation of fan archives as moments that help determine who and what is valued in historical accounts of media and fan cultures is critical since, as Trouillot (1995) explains, the creation of archives is one "crucial moment" at which silences can enter the production of history. What is excluded from an archive becomes a silence that can be replicated as those archives are deployed for the writing of historical narratives. After all, as Michel Foucault (1972) argues, archives are "the first law of what can be said" (129); they shape the possible ways of knowing and understanding an archive's subject. People, stories, and materials that are consciously excluded from or hidden within archives are, in effect, erased from history.

[2.6] Fan archives are instrumental in the creation of fan histories like the documentaries mentioned in the introduction. The League of Legends fans who create such videos work with a variety of archives as they engage in history-making: their own memory; community forums and social networking platforms like Reddit and Twitter; fan-run wikis that preserve important game play-related documents; and, most important for my discussion here, the archive of game play footage stored on YouTube. These archives are key to reconstructing the history of League of Legends because its publisher, Riot Games, actively orients players away from the game's past. The game is constantly changed through patches, software updates that players must download in order to play. With each patch, old code is overwritten, and features of the game, both large and small, are permanently changed. The game's code prevents players from accessing past versions by checking that users have the most up-to-date patch installed, meaning that seeing or interacting with League of Legends as it existed two weeks, two months, or two years before the latest patch is impossible. Other roadblocks imposed by Riot include the closing of the official League of Legends forum in March 2020, which erased a significant record of nearly eleven years of the fandom's communication. While Riot's ceaseless erasure of the past is common practice in a video game industry that orients consumers toward the future to stimulate frequent purchases of new hardware and software (Newman 2012), League of Legends fans care deeply about preserving the past of the game and its community. It is no wonder, then, that fans have taken on the responsibility of saving vital information about the game. From building wikis that store information that Riot deletes from its websites to downloading all of the official forum threads, fans have created their own vernacular curation practices (Nicoll 2017) that rely on the fan community to preserve pieces of the past.

[2.7] Though League of Legends documentary creators have a number of fan archives at their disposal, the game play footage archive is especially important. This archive is a collection of League of Legends game play videos from a wide variety of sources: fan-created "Let's Play" videos, tutorials on how to use specific characters or strategies, esports broadcasts, recordings of live streams, and more. The archive makes the creation of compelling audiovisual works possible by providing visually engaging B-roll to accompany the creators' voice overs. It is also freely and easily accessible on YouTube; all a video creator need do is type their desired search terms into YouTube's search box to find a seemingly endless list of downloadable videos provided by the platform's search algorithm. Most significantly, game play footage documents how League of Legends looked and functioned in the past. Because Riot Games prevents fans from playing past versions of the game themselves, game play footage provides a window into the game's development over time. Because documentary creators use game play footage as visual material in their work, it also has a representational role: the faces of players in the videos help to illustrate what the fan community looks like for viewers. I focus on this aspect of visual representation to analyze how the use of the game play footage archive results in the portrayal of a fan community virtually devoid of women and people of color. Scholars, like fans, recognize how useful game play footage can be in writing video game histories. However, the use of game play footage also has pitfalls. Because these videos are often created by fans for fans, they can be difficult for community outsiders to interpret (Nylund 2015). The sheer number of videos uploaded to video sharing platforms also makes sifting through all of them in a systematic way nearly impossible (Manning 2017).

[2.8] Unlike fan fiction archives and fan wikis, which are carefully constructed and organized by fan-archivists and users, the League of Legends game play footage archive I consider here is shaped by both humans and technology. Fans produce the content that populates the archive and write the metadata that makes those videos intelligible to YouTube as data. YouTube executives decide upon the business imperatives that underly the organization of the platform, and YouTube employees encode those imperatives into the algorithms that render the platform's overwhelming wellspring of content navigable for users. Machine learning technology learns from user interactions to fine tune video recommendations and search results over time. Video search and recommendation algorithms determine which videos users see, making certain content and creators visible while obscuring others. Human decisions and technological actions weave together in complex ways to determine who shows up when a fan searches through the game play footage archive. In what follows, I dig into this complex process and show how the algorithmic curation of this fan archive contributes to the hegemony of play.

3. Algorithmic curation of digital archives

[3.1] The League of Legends game play footage archive, like many other fan archives, is a digital archive that facilitates participatory fan culture (De Kosnik 2016). It is similar to other digital fan archives in its accessibility: just as anyone can upload a story to AO3, anyone can post a game play video to YouTube. Also similar is the fact that fan culture shapes who participates in building the archive. Like the exclusion of queer shipping from the Battlestar Galactica wiki, League of Legends fans shape the game play footage archive by discouraging certain people from creating content and contributing to the collection. For example, many video game scholars have shown how the racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia of video gaming and live streaming cultures make it less likely that women, people of color, and queer folks will want to open themselves up to potential abuse by recording themselves playing games (Gray 2012; Gray 2017; Nakandala et al. 2017; Ruvalaba et al. 2018; Ruberg et al. 2019; Chan and Gray 2020; Gray 2020; Woodhouse 2021). Players who are marginalized in video game fandoms by the hegemony of play are thus less likely to appear in game play videos and the game play footage archive. As we will see, algorithmic curation makes these already marginalized community members even less visible in the archive.

[3.2] Curation on many fan archives is a careful, intentional process of coding and organization. The tagging system on AO3, for example, makes it easy to survey what fan fiction stories are available, see who has contributed, and search for any combination of characters, franchises, and story tropes. This metadata system and similar systems used in other fan archives are created by fans who can imagine what the typical user will want to do as they search through and add to the archive (Johnson 2014). In comparison, an archive housed on YouTube seems like the Wild West. Finding videos through the platform's search function is easy, but the knowledge logics that guide the search algorithm's ordering and presentation of results are opaque (Gillespie 2013). It is unclear why certain videos are ranked higher than others in searches, and users have few tools for filtering and limiting the field of results. YouTube maintains a League of Legends category page that centralizes videos about the game in one place, but there is no intuitive way to access the page, nor is there any explanation for how it is curated. Judged against well-organized fan wikis or fan fiction archives, YouTube's emphasis on algorithmic, personalized selection and recommendation of content (Burgess and Green 2018) seems to make the platform a rather unwieldy archive.

[3.3] James Manning (2017) comes to a similar conclusion about the game play footage archive saved on the now-defunct video sharing platform Everyplay. Though he recognizes the significant utility of a vast collection of game play videos to video game historians, he argues that such an archive may be unusable without significant intervention from historians and archivists to help organize its materials in a systematic way. Though new media platforms like YouTube facilitate the creation of participatory archives that turn history into a more democratic and public practice (Huvila 2008), the amount of content housed in online participatory archives can pose a problem if the archive does not give guidance to users about how to explore and critically interpret the materials within (Haskins 2007). Robert Gehl (2009) calls YouTube an "archive awaiting curators" (45), pointing directly at the difficulty that anyone would face while trying to interpret the vast amount of content the platform hosts.

[3.4] However, YouTube does in fact have curators: its content search and recommendation algorithms. As Jeremy Wade Morris (2015) argues, media is increasingly digitized and data-fied, allowing algorithms that can quickly interpret and work with data to take up the job of curating and presenting culture for consumers. Though scholars often talk about algorithmic curation of culture in the context of music applications like Spotify or online television platforms like Netflix, the concept of algorithmic curation can be extended to analyze how unwieldy digital archives like YouTube are curated and presented as coherent collections of information for users. Mike Featherstone's (2006) rethinking of the archive as a decentralized, loosely classified collection of documents helps to demonstrate the potential of algorithmic curation for historians and archivists. A digital archive can store and process documents in myriad ways, allowing "the topology of documents [to] be reconfigured again and again" (596). In other words, a digital archive need not have a stringent organization scheme; the digital tools, such as metadata and algorithms, that process documents can provide a flexible organization scheme that presents information according to each user's particular query. This could allow, in theory, documents that are hidden in an archive to come to light in ways that might not be possible when following a set cataloguing system. Crucially, however, the potential of this kind of decentralized archive is dependent on the forces that configure the archive's topology of documents. If the digital and human curators that help shape how documents are processed and presented are biased in some way, then the archive's topology will show the traces of those biases.

[3.5] Following Featherstone, then, we can understand the League of Legends game play footage archive as a collection of loosely connected game play videos uploaded to YouTube. Linked together by metadata extracted from video titles, descriptions, thumbnails, transcripts of dialogue, and other information, these videos emerge as an identifiable archive only when users call upon them through searches. The materials of the archive are pulled together only when a user asks for them, and the algorithmic curator that delivers search results shapes the topology of the archive to fit both the user's query and the imperatives coded into the algorithm by its creators. The archive's topology is already powerfully shaped by a fan culture that encourages certain fans to contribute while discouraging others (Gray 2017; Nakandala et al. 2017; Ruvalaba et al. 2018; Ruberg, Cullen, and Brewster 2019; Chan and Gray 2020; Gray 2020; Woodhouse 2021), but algorithmic curation works to shape that topology into something presentable to and understandable by users. To see how the archive contributes to the expression of the hegemony of play in League of Legends fan documentaries, I now turn to critical algorithm studies to better understand the risks of algorithmically curating archives.

4. Analyzing algorithmic curation

[4.1] Analyzing a proprietary algorithm like YouTube's search algorithm with any precision is difficult. Some scholars approach algorithms as impenetrable black boxes, arguing that "we can observe [their] inputs and outputs, but we cannot tell how one becomes the other" (Pasquale 2015, 3). For example, though we know that user-created metadata such as titles and text descriptions play an important role in how YouTube algorithmically classifies videos, there is also much that we do not know: How does YouTube use the visual information in video thumbnails to categorize content? What influence do video length and amount of viewer interaction have on video ranking and visibility? We do not know exactly what factors go into the algorithm's determination of relevance for a specific search, nor do we know how the algorithm weighs each of those factors. Even if the exact mechanisms of the algorithm were determined, YouTube could easily and silently alter its algorithm at any time. Studying algorithmic curation of the game play footage archive, then, is to study an ever-morphing, always-veiled target.

[4.2] Despite this being the case, learning about and analyzing an algorithm is not impossible. Nick Seaver (2017) advocates a view of algorithms as "unstable objects, culturally enacted by the practices people use to engage with them" (5). We may not be privy to the code behind an algorithm's computations, but we can learn about how it shapes and is shaped by human actors by analyzing how those who work with, use, and interact with the algorithm talk about it. Seaver suggests using ethnography to get at the discourses around an algorithm, but his approach aligns well with Safiya Umoja Noble's (2018) method of closely reading algorithmic search results. By doing targeted keyword searches and carefully analyzing the results, Noble crafted explanations for how Google's search algorithm interpreted and presented information even if the exact workings of the algorithm remained opaque. This method of interpreting an algorithm's workings "provides more than numbers to explain results and…focuses instead on the material conditions on which these results are predicated" (61). I take a similar approach to understanding algorithmic curation. I did searches that targeted the League of Legends game play footage archive, carefully looked at the results to see what videos were promoted and which were obscured, and then considered how business imperatives, encoded biases, and fan culture worked together to shape the archive's topology in specific ways.

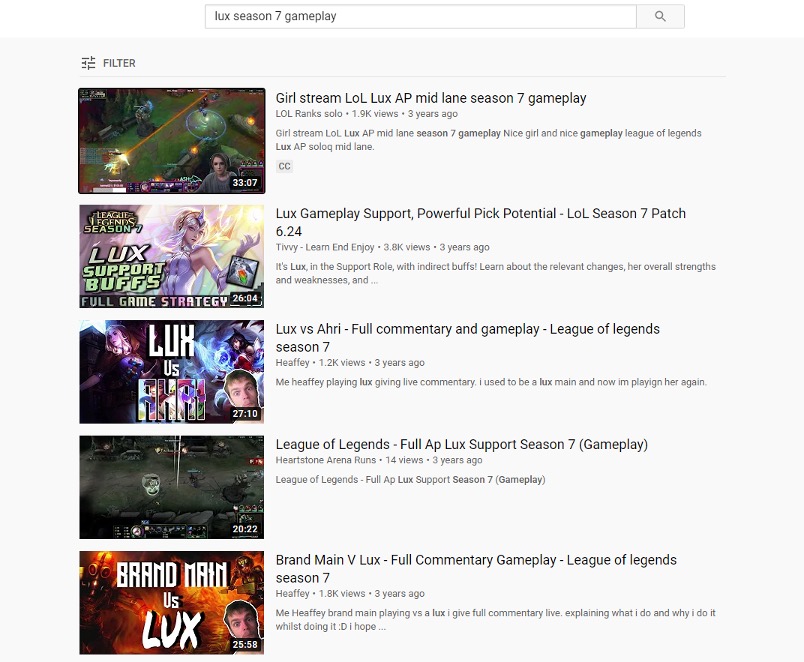

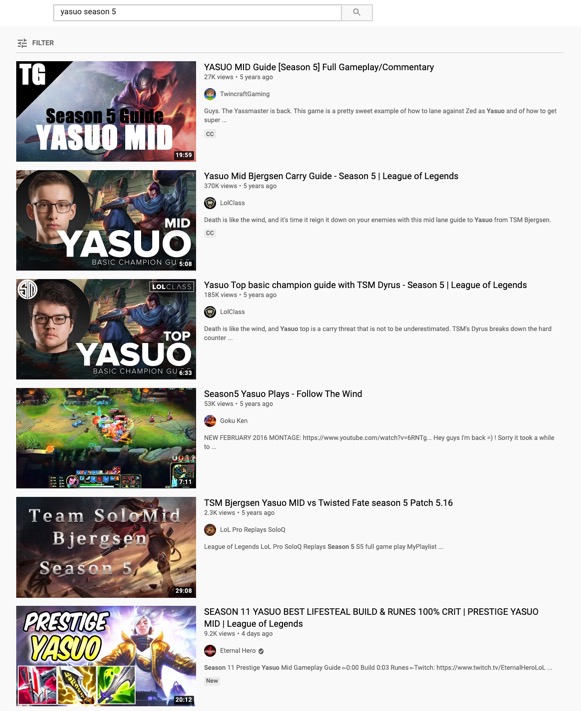

[4.3] My searches revealed that the game play footage archive's topology is clearly shaped by the hegemony of play. The screenshots below (see figures 1 and 2) show two of my searches, both of which were typical of my broader results. The two searches are for character-focused game play videos, which are an important source of evidence for character-focused documentaries. In both searches, white men's faces were the most visible, and they feature in all but one of the videos in which a human was visible. No people of color were visible in any of the videos. The second search was dominated by esports-related content (see the videos featuring players Bjergsen and Dyrus in figure 2), as were other searches for more general terms like "League of Legends season 3 games." While the first search (see figure 1) included a woman as the first search result, she does not appear to have uploaded the video of her game play herself. Rather, the video was recorded and uploaded by a highlight channel, a type of fan-run YouTube channel that uploads, with or without permission, clips of game play from a variety of live streamers. The video's title, "Girl stream LoL Lux mid lane season 7 game play," and description, which mentions "Nice girl and nice game play," suggest that the woman's physical appearance, and not her game play skills, are the main attraction for viewers. Her inclusion thus mirrors the highly constrained, ornamental roles that women have traditionally held within gaming and esports culture (Taylor, Jenson, and de Castell 2009; Ruberg, Cullen, and Brewster 2019) and does not signal a shift in the hegemony of play's exclusion of women.

Figure 1. YouTube search results for the query "lux season 7 gameplay," conducted on an Incognito Google Chrome browser on October 13, 2020.

Figure 2. YouTube search results for the query "yasuo season 5," conducted on an Incognito Google Chrome browser on December 26, 2020.

[4.4] These search results, as well as the results not pictured here, show how the hegemony of play structures the game play footage archive on YouTube. White men are hypervisible while people of color are conspicuously absent, and women are invisible except as objects of sexual attention. Game play videos by esports professionals rank highly, demonstrating the connection between the hegemony of play's emphasis on hypercompetitive game play and the veneration of professional gamers within fan communities. These findings echo Aaron Trammell and Amanda L. L. Cullen's (2020) findings about algorithmic bias in video game fandoms. Belief in the objectivity and infallibility of algorithms, they conclude, gives video game fans the language to create and maintain hierarchies within their communities that reflect and reinforce patriarchal power. A similar belief in the objectivity of algorithms can lead fans to trust that the YouTube search algorithm provides them with an accurate, unbiased view of their fan communities. On the contrary, my search results make clear that the hegemony of play strongly influences algorithmic curation of the archive. Now, following Noble, I turn to explore the material conditions that produce such algorithmic bias.

5. The archons behind the algorithm

[5.1] One way to analyze the material conditions behind algorithmic curation of the game play footage archive is to consider who writes the algorithm's code and who creates the data that the algorithm processes. While algorithmic curation is carried out by technology, humans write the coded instructions, produce the data that power the algorithm, and perform the interactions that teach the algorithm through machine learning. By considering the interactions between humans and technology, it becomes clear how a variety of factors, from the business imperatives of YouTube to biased beliefs about fan culture, play an important role in determining the outputs of algorithmic curation.

[5.2] A basic understanding of algorithms asserts that they are tools for solving a problem or achieving a goal. The YouTube search algorithm is built to achieve the goal of generating profits. As such, it is important to remember that the game play footage archive is "embedded in architectures of software, and the political economy of social media platforms" (Parikka 2012, 170). The algorithms that process and present videos on YouTube are built to serve commercial interests, and while YouTube wants users to trust that its algorithms are unbiased, such trust is unwarranted. As Noble (2018) reminds us, search algorithms are anything but neutral; they reflect the biases of those who create them, meaning that racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, and other bigoted ideologies are often encoded in algorithms by their programmers, unwittingly or not. They are also built to serve users who live in a racist, sexist, queerphobic, ableist culture, and programmers may assume that users will want results that reflect, rather than challenge, their culture. Sophie Bishop (2017) argues that YouTube's algorithms specifically "contribute to stratification by class and gender" (80), while past controversies surrounding YouTube's suppression of videos produced by queer creators and creators of color (Hughes 2015; Romano 2019) suggest that Bishop's findings likely apply beyond just class and gender. Algorithms express the desires and beliefs of those who create them and those who use them, allowing the business goals of YouTube executives, the internalized biases of programmers, and the biases of wider culture to shape the topology of the game play footage archive as it is curated by search algorithms.

[5.3] Though YouTube, like other social media platforms, deploys a variety of business strategies to extract value from users (Burgess and Green 2018), the platform's relationship to and reliance on advertising is popularly understood as the most important aspect of its business. When a creator posts a video that captures audience attention without clashing with advertisers' brand messages, YouTube benefits. The search algorithm is coded to encourage such behavior by rewarding creators whose videos generate advertising revenue with visibility in search results and video recommendations. Algorithmic processing of videos also generates analytics, or data about video and channel performance, that YouTube presents to creators on their Creator Studio platform. Analytics allow YouTube to communicate with users about how well their behavior aligns with the platform's business goals. Such mechanisms, Bishop (2017) argues, encourage algorithmic compliance, or alignment of user behavior with a platform's business goals as communicated through its algorithms. Search results, video recommendations, and channel analytics are not just byproducts of the search algorithm's operation; they are tools of communication created by YouTube to encourage users to comply with its commercial imperatives.

[5.4] The effects of algorithmic compliance can be seen, for example, in the growing trend toward the creation of longer videos; as the algorithm began to prioritize long videos, which have more room for advertisements, content creators took notice and complied with the algorithm's message (Alexander 2019). It is through algorithmic compliance that we can see how YouTube deploys its search algorithm to not only present searchers with content that will capture their attention but also to communicate with its content creators about how to perform their creative work. Importantly, users respond to such communication. Taina Bucher (2017) argues that social media users change how they interact with algorithms based upon how they believe such technologies collect, parse, and use their data. She calls these beliefs about how algorithms work the "algorithmic imaginary." Because platforms prefer not to communicate the specifics of their algorithms to users, content creators use their imagined understandings of algorithms to guide their creative work. Creators develop strategies, such as filming videos on certain topics or including popular keywords in video titles, on the basis of what they imagine the algorithm wants to see. These strategies of algorithmic optimization, to borrow Bishop's (2017) term, spread as creators observe what others have done to find success and give each other advice about how to play to the algorithm's encoded preferences. Like other creators, those who make and post League of Legends game play videos practice algorithmic optimization; as they shape how they package their game play videos to comply with the imagined whims of YouTube's search algorithm, they shape what materials the game play footage archive holds and how the search algorithm processes those materials.

[5.5] Algorithmic compliance and algorithmic optimization play a key role in shaping algorithmic curation of the game play footage archive. This became clear as I conducted searches through the archive and noticed that the channels whose videos dominated the top positions in search results were generally of three types: highlight channels (fan-run channels that compile exciting game play clips), tutorial channels (channels that teach fans how to improve at the game), and esports channels (channels that promote and broadcast professional play). Though these channel types have different goals, they are united in their desire for algorithmic visibility and the monetary compensation that comes along with it: tutorial channels and esports channels have employees to pay, while the fans that operate highlight channels often seek recognition and compensation for the work they do to edit together engaging game play compilations. As a result, these channels tended to optimize their content for the algorithm through a variety of strategies: crafting long, meticulous titles filled with keywords that users are likely to search; writing lengthy video descriptions that include as many keywords as possible; making videos long (often twenty to thirty minutes) to make room for multiple advertisements; and creating flashy, eye-catching video thumbnails with images of popular characters or esports athletes to draw viewers' attention. The widespread adoption of these strategies was clear as I scrolled through search results; videos tended to feature similar titles and thumbnails with little variation or experimentation, even as I reached the 100th or 200th video in a search. Channels that had not adopted such strategies were hidden or completely obscured by the search algorithm, and finding videos that broke the mold required specific searches: finding any video by a Black player, for example, required a query for "Black League of Legends player," while finding videos that discussed the backstory of game characters required the inclusion of the keyword "lore" in the query. Without manipulating search terms to explicitly call for diverse players or approaches to the game that were noncompetitive, finding videos that did not fit with the homogenizing effects of algorithmic compliance was nearly impossible.

[5.6] The algorithmic promotion of highlight channels, tutorial channels, and esports channels tells its own story about the League of Legends fan community and its favored approach to fannish expression. The grip of the hegemony of play is expressed both visually, through the overwhelming dominance of white male faces in video thumbnails and previews, and philosophically, as one scrolls through video after video focused on either celebrating or achieving highly skilled game play. This can be attributed partly to fan culture. League of Legends has remained popular despite being over a decade old because it facilitates competitive game play and rewards players for building and improving their game play skills (Paul 2018). It makes sense, then, that content that caters to the community's interest in high-level game play and honors players who rise above the rest would be prioritized in the algorithm's representation of the community. However, this is not the only (or even primary) approach to League of Legends game play and fandom. Many fans play casually to connect with friends, focus on the game's extensive story and lore, or create fan art and fan fiction to express their fandom. Videos showing these modes of fandom were virtually invisible in my searches. Algorithmic curation, shaped by both YouTube's business goals and fan culture, presented an archival topology that enshrined not only a specific kind of player but a specific way of approaching the game and fandom as the standard way to be a League of Legends fan. To describe the League of Legends fandom as the game play footage archive does is to tell the story of white men who excel at the game in the highest levels of competition.

[5.7] Disentangling lines of causation among the influences upon algorithmic curation is complex. It is impossible to say whether algorithmic curation follows the hegemony of play in order to cater to a preformed preference for hegemonic views among League of Legends fans or whether the promotion of videos that fit into the hegemony of play serves YouTube's business goals better than others. Likely, both are true, and the patterning of YouTube search results after the hegemony of play is a self-reinforcing loop: as fans see their community represented to them in a specific way, they begin to want similar representations, leading to the promotion of similar videos by the algorithm and the adoption of new optimization strategies by content creators to comply with the algorithm's communicated preferences. Regardless of where or how this loop began, algorithmic compliance, algorithmic optimization, and fan culture all help perpetuate it. Videos begin to cover similar topics, feature similar faces, and promote similar rhetorics of play as creators see others reap the rewards of algorithmic optimization. The algorithm curates these videos for would-be historians to see, presenting hundreds of similar videos to choose from. However, a critical look at the process of algorithmic curation makes clear that the results of such curation should not be taken for granted as an unbiased presentation of the fan community's historical record. Videos are being hidden, and an unexamined use of the archive will leave those videos and the people creating them uncovered.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] The League of Legends game play footage archive on YouTube is simultaneously liberating and limiting for those interested in the history of the game and its fandom. On one hand, these videos allow us to see and experience the past of League of Legends in ways that are impossible for us to access on our own. Because Riot Games bars players from accessing prior versions of the game, the ability to see how the game and its community developed over time makes the archive a dream for those seeking to piece together the past of the game and its fandom. However, the forces that structure the archive and influence its algorithmic curation limit its ability to fully represent the League of Legends fan community. As game play is recorded, packaged, and uploaded by various fans and industrial actors and then arranged for perusal by YouTube's search algorithm, the slice of the community represented in the archive becomes smaller and smaller, closer and closer to an image that reflects the hegemonic ways in which video game fandom is constructed as the preserve of hardcore gamers. Though esports players and highly skilled competitive players make up an extremely small portion of the global League of Legends fandom, their prominence in the game play archive and in the fan-made documentaries that draw from the archive suggests that they are representative rather than exceptional fans. As these players rise to prominence, women, people of color, and others who sit outside of this select group are pushed to the margins, reinforcing the hegemony of play. The histories written by the fans who use this archive reflect not the wealth of ways of interacting with League of Legends or the diversity of its globalized fandom but the stories of a small slice of the community.

[6.2] Though I focus here on one specific fan community, my findings about the effects of algorithmic curation upon digital fan archives have implications for fan studies more broadly. Fans care about the histories of their communities as projects like fan-made documentaries, fan archives, and wiki projects like Fanlore make clear. They draw from their community archives in the search for stories to tell and for historical evidence with which to weave their narratives. Considering how fan archives are structured to exclude certain fans and fan practices is necessary to understand what kinds of stories fans can tell about their communities and how those stories can further marginalize fans of color, queer fans, fans with disabilities, and others who may already find themselves on the outskirts of their fandom. Fan-written histories are an important tool for imagining communities, and examining them will allow scholars to more deeply attend to how fans are constructing their fandoms in exclusionary or, hopefully, inclusive and subversive ways. Such examinations can also help scholars more critically consider the stories we tell about the communities we study and the sources we use to tell those stories.

[6.3] Finally, my work here sheds light on the role that commercial platforms play in constructing boundaries around fan communities. Algorithmic curation shapes archives of fan vids hosted on YouTube, podfic saved on Soundcloud, and fan fiction posted to platforms like Tumblr and Wattpad. As these platforms become primary sites for the creation, circulation, and storage of fan works, they also become rich, if unwieldy, archives. Scholars must attend more closely to the ways that fan culture is expressed through and limited by algorithms on the social media platforms that facilitate fandom. Doing so will not only reveal how platforms are implicated in the reification and reproduction of exclusionary ideologies like the hegemony of play but can also shed light on how fans recognize, negotiate with, and make use of the algorithms that curate their communities. Ideally, such an analysis will also make it possible for us to do our work, as both scholars and fans, with more awareness of how the communities we participate in and write about are powerfully shaped not only by ourselves and other fans but by the platforms that have come to curate so much of our culture.