1. Introduction

[1.1] Here is the scene: Hanoi, in northern Vietnam, November 2012. Thanh Quang Le was an energetic, bespectacled youth in his early twenties who was also an avid fan of the A-list Korean girl group T-ara. Wearing eye-catching yellow T-shirts emblazoned with T-ara's name, Le and his friends patiently waited at the airport entrance to welcome the girl group on their visit to his home country. Holding his breath and looking for signs of T-ara, little did Le know that the chain of events that followed would turn him into an internet sensation.

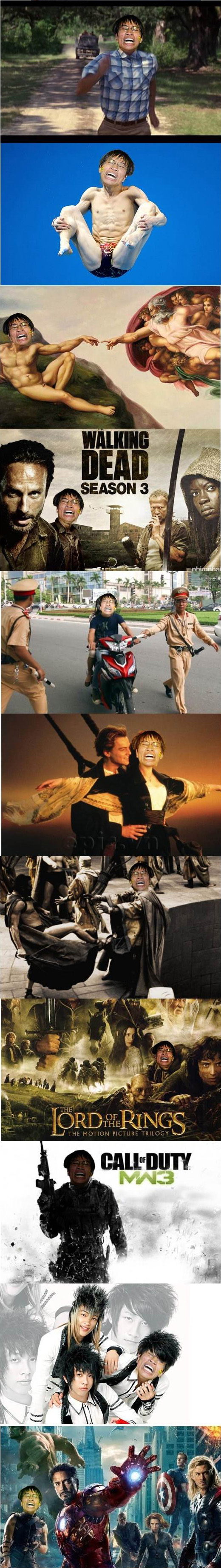

[1.2] When his Korean idols finally appeared in the flesh, Le and his gang burst into tears and squirmed in hugs and different shades of strong emotions. A journalist took photos of this overwhelming fannish moment and had them published by major Vietnamese news outlets in the following days. Although probably nowhere near the dramatic hysteria by American Beatlemanic fangirls in the 1960s discussed in the classic essay by Ehrenreich, Hess, and Jacobs (1992), one particular photo of Thanh and his friends (figure 1) was visually powerful enough to "break," as we now might call it, the Vietnamese internet (Duong 2016). Among the multiple T-ara fans that were captured, it was probably Le's striking facial expression and ardent body language to the right of the photo that attracted the most attention from the media, causing Le's image to spread like wildfire almost overnight. Unofficially given the title thánh cuồng (god of out-of-control behaviors) by Vietnamese internet users, Le's photo was remixed into satirical memes and still often brought up today when it concerns Vietnamese K-pop fans (figure 2).

Figure 1. Thanh Quang Le and his friends when their idols T-ara arrived in Vietnam in November, 2012 (Source: GenK.vn).

Figure 2. Le's photo was remixed into memes by the Vietnamese internet (Source: GenK.vn).

[1.3] Le's photo and experience was one of the many embodiments of how the Vietnamese public stigmatized the fast-growing and young K-pop fandom in Vietnam. The goals of this article are twofold: to de-Westernize fandom studies through a case study of Vietnam and to explore the complicated relationship between transcultural fandom and nationalistic discourses. As fandom studies remains steadfastly Anglo-American and predominantly focused on East Asian or inter-East Asian contexts (Chin and Morimoto 2013; Pande 2019), fandom in Vietnam remains all but ignored. Through an analysis of mainstream online news related to K-pop and public comments on these news articles, I investigate how the mainstream public discourse made sense of K-pop fandom in Vietnam, how the fans reacted to this public discourse, and how this story might have changed from 2011 to 2019.

[1.4] Chin and Morimoto (2013) call for a theoretical shift in fandom studies, from the over-deterministic nation-centered analyses of border-crossing fandoms to a broader, "transcultural" focus that zooms in on fans themselves and their myriad contexts in our intensifying global media marketplace. They argue that nation is only one in a constellation of contexts of fandom and that transcultural fandom could arise through affinities of affect regardless of geographical and cultural borders. This article does not directly apply but is in direct conversation with Chin and Morimoto's (2013) approach. Through a case study of Vietnam, I argue that even when a powerful cultural phenomenon such as K-pop has become more global and transcultural, analyses of K-pop in different national contexts are still relevant. As of now, K-pop as an industry is much different from the days of Psy's "Gangnam Style," where Western media started to have serious discussions about K-pop's potential break into the mainstream American market. With the rise of wildly successful groups like BTS and BLACKPINK, as well as K-pop groups' collaborations with Western pop stars, K-pop is already a global cultural powerhouse (Lee and Pham 2021a, 2021b). This rise, however, has caused Korean K-pop fans to debate what K-pop should look like as the K-pop industry expands its global and transcultural appeal by creating non-Korean K-pop groups and catering to the demands of international fans. It has also resulted in local pushback in countries where K-pop is perceived to be a threat to nationalistic values and the identities they want to uphold (Lee and Pham 2021a, 2021b). Vietnam is a good case in point for the latter scenario, which also includes countries like China (Chen 2018) and Indonesia.

[1.5] For this article, I am aware that my choice to look at mainstream news articles in Vietnam—where the local media is considered a state-run press with marked conservative state interests and high levels of censorship (Coe 2014)—poses the possibility of what Chin and Morimoto (2013) referred to as "national overdetermination," where an implicit privileging of a nationalistic orientation supersedes fannish engagement. To counter this, I will not just examine mainstream news articles on K-pop fans in Vietnam but will also explore the fans' reactions and resistance to these materials to shed light on how the Vietnamese fans forged their own transcultural identities and affinities of affect, especially through more participatory technological platforms such as social media and YouTube. Delineating a cultural frame applicable, but not necessarily unique, to the Vietnamese context, I argue that the Vietnamese public imposed notions of shame/pride and infantilization on Vietnamese K-pop fans. This process positioned the transcultural fans as at odds with Vietnam's national identity and heritage preservation. A similarly ambiguous history of the reception of the Korean Wave has been observed in China (Chen 2018).

2. K-pop transcultural fandom in Vietnam

[2.1] First, it is crucial to explain the fandom context in which I am researching. A country in Southeast Asia, Vietnam is often culturally associated with the Vietnam War or vibrant touristy images of beautiful landscapes and thrill-seeking activities by contemporary Western audiences. Hailed as one of the most dynamic emerging economies in Asia, Vietnam has experienced significant economic reforms, sociopolitical changes, and rising consumerism over the past thirty years (The World Bank 2019). Vietnam's steadily increasing internet and smartphone penetration rates, currently at sixty-one percent and thirty-seven percent (Statista 2019; Statista 2020), have escalated Vietnamese youths' consumption of foreign popular culture. This has given rise to hybrid youth cultures and identities traversing geographical borders but likely frowned upon by older generations. K-pop is a key example of this transformation.

[2.2] Currently a major global phenomenon enjoying ground-breaking successes in the American music industry with groups like BTS, K-pop is part of Hallyu, or the Korean Wave. The Korean Wave encompasses South Korea's phenomenal export of music, TV dramas, cosmetics, cuisine, and other cultural products that first spread through its neighboring countries, such as Japan, China, and Taiwan, in the late 1990s and subsequently took the rest of the world by storm (Duong 2016). This process of "Asianization," as posited by Iwabuchi (2002), stands for new flows of cultural influence that originate from East Asian societies and counter Western cultural hegemony.

[2.3] K-pop's Asianization in Vietnam accelerated in the early 2000s and intensified in the 2010s. A local survey in May 2019 among urban Vietnamese residents above eighteen years old showed that fifty-one percent of them liked K-pop, sixty-eight percent liked Korean TV dramas, and seventy percent had positive feelings about South Korea (Ngoc Dinh 2019). Such statistics reaffirm K-pop's current massive popularity and influence among Vietnamese fans and thus warrants our research attention. Alongside the rising popularity of Korean TV dramas, K-pop has received widespread and enthusiastic engagement, especially by young people, through national television, concerts, social media, and free user-generated online sites (Park 2017). However, Vietnamese youths' K-pop fandom engagement has encountered significant pushback from the Vietnamese public, which often expresses old-world nationalistic ideologies and communitarian orientations (Duong 2016). A fascinating site of social interactions for fandom studies, Vietnamese K-pop fandom holds tremendous potential and allows the mapping out of how the nation's postmodern market economy and self-serving orientation negotiate changing norms and power relations among its current generation of youth (Nilan 1999).

3. Methodology

[3.1] Given that being a fan has become a more mainstream identity this past decade, mass media representations of fans have gained more visibility and influence on how media audiences make sense of the world they live in (Booth and Bennett 2016). However, a literature review revealed only two extant studies in English that specifically focused on fandom in Vietnam, both of which concern K-pop (Duong 2016; Phan 2014). Building on these pioneering works, I here investigate K-pop fans in Vietnam during the period 2011–19 through an analysis of their mainstream media representations, public reaction to these representations, and the fans' reactions to their public reception.

[3.2] My analysis relies on a sample of 1,814 online news articles using purposive sampling. I gathered my sample by conducting searches using the Vietnamese search term fan Việt K-pop (Vietnamese K-pop fans) and Google News's built-in advanced time tool to generate search results based on a customized date range from January 1, 2011, to December 8, 2019. Drawing on close reading and discourse analysis, I analyzed the news articles and their public comments as texts. Because the sample does not include data through more direct research methods such as interviews or focus groups, I acknowledge that the findings to be examined here are highly mediated. I approached this research topic as a Vietnamese national who has lived in Vietnam, Singapore, and the United States with personal exposure to major trends in Western and Asian popular culture since the late 1990s and early 2000s. To have a more rounded understanding of K-pop in the 2010s and make use of the highly mediated nature of the dataset, I immersed myself in the digital space of Vietnamese K-pop fans by actively conducting more Google searches to access more news articles, fan responses, and discussion threads on social media that illuminated any news events or terms I found unclear. All the data included in this study had open access to the public and did not require registration or password login. I engaged in a manual coding process for a qualitative analysis of dominant themes arising from the news texts and public discussion of Vietnamese K-pop fans.

[3.3] The following four sections explicate my research findings by applying scholarship in fan studies, cultural studies, and media studies (in order of prevalence). Adopting an analytical and theoretical lens from both Asian and Western traditions, I detail a historical narrative of mainstream online representations and public reception of young K-pop fans in Vietnam from 2011 to 2019 and then surface characteristics of Vietnamese society and Vietnamese K-pop fandom, which entails an interesting intermingling of variegated cultural, political, and ideological interests.

4. The era of shame: 2011–13

[4.1] From 2011 to 2013, online media representations and public perception for the most part generalized Vietnamese K-pop fans as naive, disoriented, and delusional young people with excessive expressions of emotions and admiration, as well as fanatical or even obsessive actions. This representation was often manifested through a variety of reported incidents ranging from unrestrained declarations of loyalty and love for Korean idols online, screaming and crying at Korean idols in real life, to crowding at airports, waiting for hours, throwing superfluous welcome for, and chasing after Korean idols when they arrived in Vietnam for performances. On top of this came reports of fans' aggressive, antagonistic, or even vulgar online responses to those who questioned or rebuked their fanaticalness. These fans might proclaim that Korean idols made their youthful lives much more meaningful and then undermine their critics as inferior to their idols and Korean culture.

[4.2] In this period, Vietnamese K-pop fans' expressions of fannish identities were often repressed. The Vietnamese public often referred to them with the patronizing terms fan cuồng K-pop (out-of-control fans of K-pop) and trẻ trâu (water buffalo youth). The term trẻ trâu is most probably a metaphorical association of fanatical and strong-willed Vietnamese K-pop fans with the sturdy water buffalo widely domesticated and deployed in Vietnam's rice agriculture, and it is likely related to the Vietnamese common saying lì như trâu (as stubborn as a water buffalo). This generally negative representation concerned the Vietnamese public considerably, causing widespread condemnation of K-pop fans. The public felt K-pop fans should be ashamed of themselves and take necessary measures to rectify their supposedly irrational fanatical behaviors. In other words, there existed a top-down expectation that young K-pop fans should realign their impressionable mindsets with the norm, including an appreciation of local Vietnamese culture and their everyday relationships with family members, instead of being spellbound by the foreign influence of Korean popular culture. My findings agreed with Duong's pioneering work (2016) on Vietnamese K-pop fandom from 2012 to 2015, in which she examined K-pop as a form of cultural imperialism with a strong focus on fans' perspectives but did not address the roles that Vietnamese cultural characteristics played in arguments surrounding fandom.

[4.3] The A-list boy group Super Junior's arrival in the capital city Hanoi in 2010 and media coverage of Vietnamese fans' over-enthusiastic welcome at the airport is arguably the event that sparked widespread public dismay and criticism of K-pop fandom in Vietnam. The fans reportedly chased after the idols' bus in the middle of the street (figure 3) (Nguyen 2017), and the same enthusiastic greeting was repeated in 2011, when the band returned to Vietnam. Heated debates erupted online in response. A news article on the leading daily newspaper Tuoi Tre explicitly censured Super Junior's K-pop fans as young people with too much free time and pocket money. They were portrayed as "obsessed" with their idols to the point of being "possessed" (Tuoi Tre Online 2011) by citing selective comments from the public:

[4.4] I am not even sure if these fans actually admire [Super Junior]. They jump on the [cultural] bandwagon, but don't exactly know what is going on.

[4.5] I am also a young Vietnamese person, but I will never behave like these young, mixed-race, disoriented fans. We should save our tears to cry for our nation and our people's pain. These fans only absorb silly, meaningless [Korean popular culture]. If only they were able to digest advanced science technologies from overseas this fast!

[4.6] I understand that an idol culture truly exists, but is there a need to diminish our [Vietnamese] traditions this much? Don't be so crazy and book a flight ticket just to see your idol. Too nonsensical!

[4.7] Although the article cited a response from a K-pop fan, who urged the public not to see the fans as "irrational youth who favors foreign values [over Vietnamese values]," its overall tone toward the fans was generally condemnatory.

[4.8] The comments that some fans deserved censure for being "mixed-race" strikingly highlights how the public considered fans' individual consumption of foreign popular culture "nonsensical" and in direct opposition to the public's national identity. "Mixed race" would likely be considered a racist and derogatory term in the United States or other racially and ethnically diverse countries. However, within the highly homogenous context of Vietnam, the phrase choice "mixed race" was used in this comment to refer to Vietnamese culture mixing with Korean for descriptive purposes. It is a rhetorical shorthand that reflects the older generation's fear of K-pop as a foreign cultural force overtaking Vietnam's long-standing communitarian and hegemonic patriotic ideologies. Given Vietnam's highly homogenous population and the critics' old-world communitarian orientation, the question of one's choosing between being a Vietnamese national and a K-pop fan seemed to be an either/or—an unspoken directive to uphold the older generation's conservative values and resist K-pop as a foreign force that precipitated selfish indulgence and lavish spending. Another article on Tuoi Tre (Tran 2012) directly questioned to whom these young fans should pay more respect: their parents or their Korean idols. The article took a rather critical stance on K-pop, arguing that Vietnamese parents had sacrificed for the fans in raising them but that the fans had apparently failed to fulfill their filial duty by spending their parents' hard-earned money on K-pop idols, whom they did not even know personally. Citing opinions from both sides of the issue, the article pointed out ongoing public disputes about fans' roles as children of their families versus fans' freedom of identification with K-pop. There existed a rigid dichotomy between the two: they are either delusional school-going individuals without an appreciation of their family members or stubborn youth who would go to great lengths to protect their idols and live life to the fullest through fannish activities. The article acknowledged the sentiment shared by many Vietnamese K-pop fans that their appreciation for their K-pop idols was not groundless but built on a long-time appreciation of the idols' grueling but inspiring journey from trainee to performer. Yet, a lack of an empathy toward the fans is palpable.

Figure 3. Vietnamese fans chased after the bus that carried Super Junior in Hanoi, 2010 (Source: Kenh14).

[4.9] The public debate over Vietnamese K-pop fans gained nationwide awareness in July 2012. Vietnam's Ministry of Education decided to include this essay question in the make-or-break university entrance exam across the country, which accounts for 30 percent of one's final grade: "Admiration in the idol culture is beautiful and civilized, but blind infatuation is disastrous." Although there was no explicit mention of K-pop, Vietnamese K-pop fans' idol culture was seen by many internet users to be the elephant in the room (Duong 2016; Tuan Tu 2012). Many public comments supported the exam question as a crucial intervention in disciplining the fans. Those who were most supportive of it decried the fans as a generalizable whole and demanded more appreciation of local traditions (Tuan Tu 2012):

[4.10] I am sorry to ask, but has your [K-pop] idol ever raised you up?

[4.11] This year's exam question is fantastic. If you are indeed these crazy fans, you should know who you are.

[4.12] Young people are crazy about K-pop yet totally ignorant of Vietnamese music.

[4.13] Four months after this development, the public shaming of the fans reached a new milestone with the publication of the iconic photo of Thanh Quang Le, discussed at the beginning of this article. Clearly, the ways that Vietnamese internet users poked fun at Le's fannish behavior embody a rather stony culture of internet shaming and further ingrain Vietnamese K-pop fandom with the notion of shame. An abundance of public comments rebuking or bashing Vietnamese K-pop fans can easily be found on major online news sites dating back to 2012 and 2013. There even existed a handful of anti-Kpop fans groups on Facebook in Vietnamese that were drastically different from the professional reporting style of mainstream journalism. These Facebook groups were most likely user-generated for satire and/or informal debating purposes. They used memes, informal language, and teenage slang to mock K-pop fans. One example of such a group is "Hội những người tẩy chay fan cuồng Kpop" ("People who boycott out-of-control K-pop fans"), created in April 2013 with 5,924 Facebook likes as of December 2019 (https://www.facebook.com/anti.fan.kpop). The social stigmatization of Vietnamese K-pop fans was so intense it generated its own domestic antifandom (Duong 2016).

[4.14] The fans responded to such shaming via mainstream news sources and Facebook. On mainstream news sites, curated online commentaries reportedly written and submitted by the fans demonstrated diplomatic and deferential attempts to engage in a civilized debate with the older generation about K-pop. In a commentary titled, "The Voice of a Young Person Who Is Very into K-pop" (Nguyen 2012), a self-identified Vietnamese K-pop fan compassionately wrote the following to bridge the gap between the fans/children and their parents, humbly suggesting that their engagement in fandom might only be a transitional phase:

[4.15] We are still young so of course we are into things that are lively and flashy. This phase will pass when we grow older…Parents really are not able to understand us, but they impose their thinking on us. I object to this. Our generation is very different from our parents' generation.

[4.16] A public comment below this commentary piece politely echoed the same thought, but in a much less pacifying tone:

[4.17] Adults should guide, not force, the next generation on what to do. Don't ask why young people these days don't know a single Russian word, why they don't know any Russian songs besides [the hugely famous song] "Katyusha." Please let us choose our own paths.

[4.18] It is illuminating here that the commenter references adults who, by way of conjecture, must have grown up during the Vietnam War period, been heavily influenced by the Soviet Union's Marxist-Leninist orientation, and considered the Russian song "Katyusha" the golden standard of music. By mentioning the presumably outdated expectation that Vietnamese youth should know more about Russian culture than other Asian cultures, the comment can be seen as a comeback to adult critics' suggestion that fans who consumed too much K-pop are "disoriented" and "diminishing [Vietnamese] traditions." If enjoying K-pop diminishes one's national traditions, then how about Russian music? This commentator highlights the multiplicities and subjectivities of what the public considers acceptable cultural forces based on different generations' standpoints.

[4.19] Fans' responses to their adult critics on Facebook were less restrained than those shared in newspapers. To express their disagreement with the 2012 entrance exam question, hardcore K-pop fans created a Facebook group in which they called to boycott the exam question, voiced their anger, and even threatened to inflict harm on their critics (Tuan Tu 2012), all the while vehemently declaring love for their idols:

[4.20] If I fail the entrance exam this year, I can retake the exam next year. But my love for Super Junior is forever unchanged. I love [Super Junior] forever.

[4.21] These rather extreme display of fandom caused two observable consequences: some critics relied on this evidence to bolster their critical stance, while some fans emphasized the existence of other groups existing under the umbrella term "Vietnamese K-pop fans." For instance, one group of fans on Facebook subtly distanced themselves from extreme fans by writing about their passion for K-pop, possibly with the goals of empowering themselves and disciplining other fans into more tempered modes of fannish engagement (iOne 2012):

[4.22] I have an idol who is a singer. You might have your own idols in various other walks of life. Having an idol makes me a better person. Anything that is too excessive is indeed disastrous, including the idol culture…[But buying my idol's albums, going to their concerts, crying for them] is not a disaster to me. It's passion. Being young without passion is a waste of youth.

[4.23] In brief, the abundant presence of condemnatory sentiments against K-pop fandom during 2011–13 reflects the Vietnamese public's stringent maintenance of the unquestioned rectitude of conventions and national pride. As the online debate progressed, different sub-groups of Vietnamese K-pop fans started to come to grips with public shaming in different ways and attempted to negotiate their transcultural fannish identities by balancing them with the local values their critics expected them to uphold.

5. The era of shame and pride: 2014–19

[5.1] The period from 2014 onward witnessed a significant shift in the dominant public narrative about Vietnamese K-pop fans. The notion that Vietnamese K-pop fans should be ashamed of their behaviors persisted in news and online discussions, but its significance subsided. A new thread of representations and public reception emerged, communicating that Vietnamese K-pop fans should be proud of themselves for attracting attention to Vietnam from the K-pop industry and other international K-pop fan communities.

[5.2] The linking of Vietnamese K-pop fans with Vietnam's national pride from 2014 to 2019 coincided with an unprecedented number of K-pop concerts and award events held in Vietnam. These featured an unrivalled number of A-list K-pop idols, including the boy group JYJ's Asia Concert Tour, The Return of the King in 2014; the HEC Concert in 2014 (with MissA and Girls' Generation); the flagship show Music Bank's Global Concert in 2015 (with EXO, Shinee); the prestigious MAMA Mnet Asian Music Awards Premiere in 2017 (with Wanna One, Seventeen); and most recently, the AAA Asia Artist Awards in 2019 (with Super Junior, TWICE, Red Velvet, and many others). Several news articles in this period argued that this stream of events and attention probably had less to do with Vietnamese fans and was more likely either a byproduct of increasing diplomacy between South Korea and Vietnam or a promotional stunt for South Korean broadcasters (Vu 2017). Yet the mainstream media adopted an optimistic tone that conveyed a sense of pride in Vietnamese culture's incorporation into the K-pop idols' performances in these shows. Media also saw this shift as K-pop's official acknowledgement of Vietnamese fans and their value, as Korean idols were now offering them live events in Vietnam—a country which had previously largely been ignored by the K-pop industry. An article written by Nghiem (2017) argued that the influx of major K-pop events and artists into Vietnam around 2015–16, with strong support from Vietnamese fans, was a convincing indicator that Vietnam had become the new "land of promise" for K-pop. It further argued that Vietnam now held a competitive edge over Thailand and Singapore, considered strong Southeast Asian competitors because of their large economies and sophisticated societies. No longer depicted as shameful, Vietnamese K-pop fans were praised in the article for convincing K-pop idols to perform in Vietnam instead of its neighboring countries. This praise acknowledged the fans' enthusiastic yet appropriate spectatorship at the Music Bank 2015 concert site and the fans' increasing purchasing power. Vietnam's name was now proudly joined with K-pop's global appeal, and the nation was included in K-pop's international fandom landscape.

[5.3] More, upon coming to Vietnam, multiple K-pop idols engaged in fan service by speaking in Vietnamese and/or covering Vietnamese pop songs in Vietnamese on stage, which received generous praise from both local news and audiences. One news article reported that the impressive Vietnamese pronunciation of K-pop idols covering the hit Vietnamese song "Yêu lại từ đầu" ("Love Again") at Music Bank's Global Concert in 2015 made Vietnamese fans and the composer proud (Zing 2015). Another (Tran 2019) argued that AAA 2019's being held in Vietnam was a "cultural landmark" in establishing Vietnam's status as an international K-pop concert destination and conveyed a compassionate opinion of fans:

[5.4] This is the first time that Vietnam welcomed more than 100 artists from Korea…including the hottest artists at the moment including Super Junior, TWICE, Red Velvet…Although AAA 2019's red carpet was brief, it is the super red carpet of the year in Vietnam…It is the most extravagant K-pop stage with the biggest crowd ever…after five years since Music Bank in Hanoi. Vietnamese fans' enthusiasm for the show is understandable. The special projects that Vietnamese K-pop fans have brought to the show have definitely left such an unforgettable mark among the Korean artists and international K-pop fans.

[5.5] A second factor that shifted the public perception of Vietnamese K-pop fans was a new transcultural sensation: K-pop fans' dance covers on YouTube. These dance videos were created by groups of young K-pop fans around the world, including in Vietnam. The fans expressed their love by copying their favorite K-pop choreographies, restaging the performances either inside a studio or in public places with carefully curated costumes. They filmed their dance covers and posted them on YouTube. This genre of fan videos has become so popular that top entertainment companies in South Korea, such as YG Entertainment and BLACKPINK's Jennie (AllKpop 2018), are increasingly holding dance cover contests by inviting international fans to post their dance covers on YouTube within a deadline before announcing the winning groups and their countries of origin. No longer repressed, YouTube-based K-pop fannish identity expressions were finally legitimized.

[5.6] First appearing in Vietnam around 2011, it took years for Vietnamese K-pop fans' dance cover groups to win South Korean dance cover contests. However, they eventually did and gained national attention. One notable news article (Kenh14 2019) detailed a long list of achievements by various Vietnamese dance cover groups under the headline, "On a Winning Streak in International Dance Cover Contests, Vietnamese K-pop Fans are Leaving International Fans in Awe." A simple search on YouTube for the names of these groups (such as St.319, B-Wild, S.A.P) will return many near-professional, edited dance cover videos with tens of millions of views and thousands of comments in various languages (figure 4). The tide has turned: A few years ago, Vietnamese K-pop fans endured a domestic antifandom on Facebook; now they have their own domestic and international fandom on YouTube. A few years ago, the fans were forced to react to nation-wide criticism in opinion pieces, comments, and Facebook posts; now they can voice themselves on YouTube and attract positive mainstream news reports from the critics who had previously denounced them.

Figure 4. A screenshot of a YouTube dance cover performance by the Vietnamese group S.A.P that has received over 22 million views as of December 2019. The group has had 262,000 subscribers.

[5.7] To return to the notion of shame, I would like to emphasize that the entrenched public stigmatization of Vietnamese K-pop fans as hysterical, obsessive "out-of-control water buffalo youth" continued to exist in 2014. Just one week before I embarked on writing this article, the online news site Vietnamnet (2019) posted an article titled "Vietnamese [K-pop] Fans Flew Like Arrows into the Stadium and Stomped on One Another at AAA 2019," with an attached video recording showing young fans patiently queuing and waiting for their idols with banners or excitedly rushing into the stadium to reserve a seat. Aside from employing hyperbolic language like "flying like arrows" to describe fannish behaviors, it is worth noting that the alleged "stomping" remains unproven, with no video evidence provided. Underneath this video was a public comment very much in sync with the fan-shaming sentiment common prior to 2014:

[5.8] [These people] are out of control because they have mental problems. I am sad that there are many out-of-control [fans] like these.

[5.9] Nonetheless, overall, negative commentary gave way to more positive commentary from 2014 onward.

[5.10] In the next two sections, I will offer a cultural frame to explain the shift in the public narrative about K-pop fans in relation to Vietnam's face-saving values and the Vietnamese public's infantilization of the fans.

6. More "face" work than "fan" work

[6.1] I contend that the shame and pride associated with transcultural K-pop fans in Vietnam is related to the nation's face-saving culture. Not unique to Vietnam, the concept of "face" originates from Chinese culture and has considerable resonance with many other Asian cultures (Ho 1974). Face, in its most general sense, refers to a person's or a group's reputation and prestige, attained by maintaining standards of behavior, and it can be lost (to "lose face") or regained (to "save face"). Individuals' face is therefore related to a social consensus about them (Ho 1974). In this case, the public generalized and judged Vietnamese K-pop fans based on a conservative interpretation of fannish behaviors in relation to Vietnamese nationalism and heritage preservation (their face work) rather than in relation to an empathetic understanding of their fannish perspectives (their fan work). The older generation used nationalistic sentiments as a collective pressure imposed on the youth. This pressure relied on shaming youth for their failure to uphold their heritage and for giving in to cultural imperialism (Duong 2016). More, this pressure included a suggestion that through their out-of-control behaviors, the youth were losing not only their own face but also the faces of their family and their nation. This process is in line with Ho's concept of face (1974), which posits that the question of whether an individual's face is lost is beyond their control. Their face will be gained or lost if they succeed or fail to meet the requirements society places upon them, not through how they actualize their own personal identities.

[6.2] This top-down position adopted by the older generation effectively created widespread erasures and biases in representations of K-pop fans. These failed to highlight fans' challenging and liminal position as they juggled cultural expectations from two different countries. Using the concept of face to examine transcultural fandom in Asian societies (especially those influenced by Chinese ideologies) helps bring the notions of shame and pride the public imposes on fans into particularly sharp relief. The face-based notion of shame is arguably a more distinctly Asian example of what Western-based fandom studies' calls fan pathologization and stereotyping, which characterizes fans as geeks, nerds, losers, or hysterical and obsessive crowds (Booth and Lucy 2016; Ehrenreich et al. 1992). Very few studies have examined shame and pride in relation to fandom (Anderson 2012; Booth and Kelly 2003). It appears that fan pathologization does not necessarily lead to fan shaming but could evoke harmless curiosity or even sympathy (Deller 2016), while fan shaming is more likely to emerge as a result of existing pathologization (Anderson 2012).

[6.3] What the Vietnamese fans could do to national pride seemed to matter more than what the fans could do for their own identity formation or their fandoms. The fans were evidently entangled in a politics of fan shaming filled with contradiction and duality (Hills 2016): K-pop fannish engagement was publicly perceived as being both ideologically threatening and economically promising. That is why during 2011–13, the fans' engagement with K-pop's popularity was widely condemned and considered to be antithetical or threatening to Vietnamese traditions and heritage. Then, during 2014–19, despite Hallyu's even more aggressive penetration into Vietnam, K-pop's foreign origin and the fans' transcultural characteristics were normalized. This normalization was caused by the influx of K-pop events held in Vietnam and the sensation around Vietnamese K-pop dance cover groups on YouTube believed by mainstream Vietnamese news to have brought the country's name to international fandom's consciousness and thus to have expanded the local market economy. Park (2017) has argued that Hallyu has never merely been a cultural flow from South Korea to Vietnam but is promulgated by South Korea's state policies and governmental institutions. Their goal was to expand the global reach of South Korean businesses, especially in retail, electronics, and film production, as well as to increase public diplomacy between the two countries. If this indeed has been the case, and given the proliferation of Korean dramas that were allowed to be broadcast on Vietnam's national television by the Vietnamese government since the early 2000s (Park 2017), to what extent should the fans bear public shaming?

[6.4] In this regard, YouTube-based transcultural fannish engagement and exchange has played a pivotal role in gradually balancing out face work with more fan work. YouTube has empowered the youth to reduce public generalization of fans, actualize their affinities of affects, and promote their self-representations. Conducting ethnography with K-pop dance cover groups in Hanoi, Phan (2014) argued this fannish movement reflected that Vietnamese fans are active prosumers who create new cultural products and meanings. They thrived on and further promoted what Henry Jenkins (2006) called "participatory culture" within the space of transcultural K-pop fandom. On YouTube, it's not just about what the fans do to express themselves but also what the fans create to generate even more meaningful fannish engagement. The fans' timely and fitting appropriation of YouTube as the hosting platform to showcase their dance cover talent has aptly opened a participatory online space to elevate their idol love to an artistic and international level. This sizeable success provided them with even more agency to redefine their fan work and receive transcultural acceptance for a practice that would otherwise have been sidelined.

[6.5] Vietnam's ambiguous reception of the Korean Wave and fan pathologization is similar to the reception of the Korean Wave in China (Chen 2018). Popular K-pop groups such as H.O.T had already won over a large Chinese fanbase in the mid-1990s, while there was strong evidence suggesting the importation of Korean dramas into China in the early and mid-2000s was sponsored by China's cultural policy to strengthen the cultural exchange between the two countries. Yet aversion to and protest against the Korean Wave were continually present. These peaked in 2007–10, when Chinese Hallyu fandom—publicly criticized as "young," "unpatriotic," and "mentally damaged" for behaviors such as sending luxurious gifts to their idols—were caught between nationalistic discourses and fannish identities. They even found themselves becoming victims of hacking and spamming by anti-Hallyu fans (Chen 2018). For example, some former fans felt cheated that South Korea was, in reality, not as advanced and beautiful as it appeared on screen, while others stated they felt insulted that Korean dramas had portrayed China as a backward and poor country despite China's vast lands, ample resources, and rapid modernization. These former fans thereby argued for China's superiority and attempted to reinforce national pride and a sense of Chinese superiority over South Korea. Such public stigmatization and marginalization imposed on Chinese Hallyu fans caused them to strengthen their own self-patriotic education on online fandom forums and declaring their priority for national pride over their fandom identities (Chen 2018).

7. More youth identities than fannish identities

[7.1] I attribute the public anxiety, especially from 2011 to 2013, over K-pop's spellbinding influence on Vietnamese fans and its possible effects in eroding Vietnamese family values to a public process of infantilizing the fans. In the traditional Vietnamese family, the hierarchy between parents and their children is pronounced. This structure is strongly influenced by Confucianism. Parents are expected to raise, support, educate, and discipline children, as well as to protect them from social evils. Children are considered the main source of happiness in the domestic space and are in turn expected to practice filial piety and show respect to their parents and other family members (Burr 2006). Because Vietnamese K-pop fans were generalized as "water buffalo youth" who still depended on parental support, they were likened to impressionable, disoriented, and angsty children or adolescents with a need for guidance from senior family members. Assumptions about their childishness explain, in part, why their fannish identity expressions were repressed by the public, which was presumed to hold more collective wisdom. The fans' voices were not always heard. Their fannish identities were overshadowed by their youthful identities. Public anxiety, if not public panics, surrounding their fannish behaviors was justified by the Vietnamese media as a necessary intervention to humble and discipline the fans into Vietnamese moral standards assigned to children and adolescents in a family. A similar tendency could be observed in China, where fans of Hallyu have been continuously portrayed by the local media as being "young," "fanatic," and "rebellious" agents in need of moral campaigns and more nationalistic cultural policies (Chen 2018). When the Vietnamese fans chose to speak up for themselves in response to the public anxieties surrounding their engagement with K-pop, they did so on Facebook more often than on mainstream news sites, presumably to avoid their adult critics' direct gaze. This platform fragmentation accentuates Facebook's role in providing a less stifling outlet for the fans as compared to the more traditional mainstream news sites. While the fans' responses to their critics on mainstream news sites were explicitly addressed to "parents" or "adults," the same responses on Facebook were not directed to any specific groups of adults and read as if they had been written by fans, for fans. In other words, the authoritativeness on mainstream news sites rather bluntly disregarded the fan's justifications for their idol culture before it could even be articulated. Facebook, on the other hand, enabled the fans to express their own feelings on the matter.

[7.2] It is true that from 2014 onward, the public shaming of the fans was gradually replaced by a public celebration of the dance cover groups' winning streak in international contests. However, this achievement-based transition arguably parallels the Vietnamese society's valorization of children's achievements in a high-stake testing culture. Vietnamese parents have been found to expect or even pressure their children to perform well academically to secure a better future for themselves (Pham and Lim 2019). In many ways, the public infantilized the fans with traditional children/adolescents-oriented social norms and expectations, while the informal social skills and cultural capital these youth accumulated from being fans never received attention. YouTube's empowering role in fostering a participatory space for the Vietnamese fans to express their fannish identities and resist public shaming evokes Beatlemania's American fangirls' resistance of the sexual repression of female teenagers in the 1960s (Ehrenreich et al. 1992), although the two cases are culturally and temporally incomparable.

8. Conclusion

[8.1] Online media representations and public perception of transcultural K-pop fandom in Vietnam, as well as the fans' reactions to them, from 2011 to 2019 are sites of much contestation. In charting the developments of the public discourses surrounding K-pop fans in Vietnam, I found that these understudied fans underwent initial social stigmatization before receiving more recognition and positive public attention. Over nine years, there was a shift in the public narrative: The fans were first portrayed as shameful from 2011 to 2013. Then, they were portrayed as both shameful and as sources of pride from 2014 to 2019. I have also highlighted how the fans responded to their adult critics on mainstream news sources and Facebook.

[8.2] I have proposed a cultural frame of analysis not necessarily unique to the Vietnamese context to explain these findings in two main threads: First, the shame and pride sentiments the public imposed on the fans is due to Vietnam's face-saving culture that dictates how consensual judgment should be made. To the extent that Vietnam's old-world nationalistic ideologies and communitarian orientation were concerned, adult critics and mainstream news assessed the fans based on what value or damage they brought to the nation's reputation and standards of behavior rather than on a concomitant and empathetic understanding of who the fans were. Second, the public infantilized the youth by viewing their fannish identities through the lens of the subordinate role children hold in the traditionally hierarchical Vietnamese family. To sum up, Vietnamese K-pop fans' fan work and fannish identities were initially largely displaced by face work and youth identities. From 2014 onward, the fans were subsequently recognized, largely thanks to the international attention and transcultural cultural exchange they received through an influx of high-profile K-pop shows. This shift was further catalyzed by their game-changing appropriation of YouTube as a platform for fannish dance covers and virtual interactions with audiences across the globe. I have also compared the case of Vietnam to that of China (Chen 2018), both of which share a rather ambiguous history in their reception of the Korean Wave, as well as a tendency to stigmatize and pathologize young local fans.

[8.3] Vietnam is a developing economy that imports cultural products more than it exports them. By focusing on mainstream media representations of K-pop fandom in Vietnam, I wish to emphasize the call for attention to an increasing Asianization influence in Southeast Asia. This process goes beyond Asianization's initial goal of de-Westernization (Iwabuchi 2002) and toward fostering pan-Asian identities, and as such, poses new challenges in building cross-border dialogues about the transcultural circulation and consumption of East Asian popular culture. It additionally underscores the power relations not just between the steadfastly Anglo-American fandom studies field and the under-studied fandom sites in Asia but also between nationalistic interests (often enacted through local mainstream media systems) and fan communities within those under-studied fandom sites (Pande 2019). In other words, the transcultural K-pop fandom in Vietnam is contingent on the representational authority from both the Global North and its own local mainstream media. A more sophisticated understanding of both Western and Asian traditions will be required in future research in this area.

[8.4] Perhaps most importantly, through a case study of Vietnam, I have demonstrated that even when a powerful cultural phenomenon such as K-pop has become global and transcultural, analyses of K-pop in different national contexts are still relevant (Lee and Pham 2021a, 2021b). This article's focus on K-pop has helped to reveal and complicate various cultural, political, and ideological subjectivities in contemporary Vietnam. It has also posed new opportunities and challenges for cross-border dialogues about global circulation and consumption of East Asian popular culture, ultimately toward our increasing attempts to de-Westernize fandom studies.