1. Introduction: Fan fiction and premodern literature

[1.1] A 2014 webcomic by R. E. Parrish that went viral in fan fiction communities depicts a man in medieval Italian dress, writing on parchment with a Mona Lisa–esque smile on his face (figure 1).

Figure 1. R. E. Parrish. October 7, 2014. https://reparrishcomics.com/image/99437760558.

[1.2] The (divine?) comedy of this web comic lies in juxtaposing one of the most important works in the Western literary canon with not just fan fiction but Mary Sue fic, the subgenre most often stereotyped as clumsily written teenage erotic fantasies. And yet, behind the joke lies a compelling and oft-made observation about fundamental similarities between fan fiction and the intertextuality of premodern literary culture (note 1). It is a cliché of primers on fan fiction to trace it back to authors like Milton, Shakespeare, Chaucer, Virgil, and Dante. Comparisons between fan fiction and premodern literature are also common in classrooms. Assigning students to write a new Canterbury tale, for example, is a common assignment. By making this comparison, teachers can make space for students to repurpose the hermeneutics of adaptation that they have developed within fan communities to read early modern, medieval, and classical literature that they may otherwise find inaccessible. Moreover, an emerging field of premodern fan fiction studies has shown the potential of taking seriously this juxtaposition of fan fiction with much older literatures, but it has yet to reach any kind of consensus on methodology, in part because of unaddressed but fundamental disagreements on exactly what fan fiction is.

[1.3] In order to talk about premodern fan fiction, we must first answer the question, "What are the essential qualities of fan fiction, and which are transposable beyond its twentieth- and twenty-first century cultural contexts and can be applied to the literatures of other times and places?" This article, inspired by the "Fan Studies Methodologies" special issue of Transformative Works and Cultures edited by Julia E. Largent, Milena Popova, and Elise Vist (2020), proposes three methodological paradigms for premodern fan fiction studies, with the hope of being useful to readers interested in practicing this interdisciplinary work in their research or pedagogy. I describe three theoretical axes along which we might read historical texts through the lens of fan fiction: poaching, transformation, and affect. These three axes each correspond to different definitions of fan fiction, each of which foregrounds different characteristics: its legal status, its relationship with other texts, and its relationship with readers (note 2). Although I have worked most with the affect axis, I don't propose that any of these approaches is more valid than the others. Each opens up different avenues of historical research. The poaching axis points toward institutions of textual authority, transformation toward formal elements of literature, and affect toward historical reading communities. By laying out what I see as these three axes of approach, I hope to offer more theoretical clarity for future work on premodern fan fiction.

[1.4] In reading premodern literature as fan fiction, there is more at stake than historical accuracy. While Parrish's comic perhaps leans more toward poking fun at the Inferno than suggesting that "My Immortal" should be taught alongside it, its humor partly arises from the tension between these two possibilities. Suggesting that august canonical authors like Dante wrote fan fiction may serve to puncture reverence for a literary canon that still dominates high school and university curricula; it could equally make an argument for fan fiction's place in that canon. Indeed, claiming authors like Shakespeare and Virgil as fan fiction's literary ancestors has had significant strategic value for defenses of fan fiction's artistic validity and even legality: one of the earliest published defenses of fan fiction under US copyright law, Rebecca Tushnet's 1997 article "Legal Fictions: Copyright, Fan Fiction, and a New Common Law," references Harold Ogden White's seminal 1935 book Plagiarism and Imitation During the English Renaissance as part of its argument (652). In that same article, we hear from a fan who spoke with a lawyer for Fox Broadcasting: "I went on to talk about how many of the works of Chaucer and Shakespeare were fan fiction…and that the entirety of Western literature emerged from an oral tradition that is at its basis fan fiction" (quoted in Tushnet 1997, 656). Fan fiction's real or imagined relationship to premodern literature has had, and will continue to have, real-world consequences for fan fiction's legal and cultural circumstances. This makes interrogating the basis of this relationship essential, not only for scholars of premodern fan fiction but for fan fiction studies in general.

[1.5] Any approach to premodern fan fiction must begin by assessing the limits of transhistorical comparison. Fan fiction is an historically situated literary form, shaped by a postcopyright, postprint, post-age-of-reproduction cultural landscape. The term "fan fiction" has existed since only the 1960s, and while it flourished in amateur printed zines for the first twenty or thirty years of its existence, its primary medium shifted with technological and legal changes in the 1990s, and it can now firmly be called a digital literature. It circulates for free in what has been called a gift economy but is intimately bound up with the media marketplace under late capitalism (De Kosnik 2009; Guarriello 2019; Hellekson 2009; Turk 2014). Fan fiction is also closely associated with a community with specific demographics that do not easily map onto many premodern reading communities. The members of fan fiction communities on whom fan studies has tended to focus—online, Anglophone, focused on Western media sources—are almost all cis women or people of minoritized genders, including trans men and women and people who identify as gender nonbinary, genderfluid, or agender. Many fan fiction readers and writers in these communities are between the ages of eighteen and twenty-four, the majority are white, and a far higher percentage than in the general population identify as LGBTQA+, queer, or otherwise of a sexual minority (note 3). Given all this, applying the term "fan fiction" to the Aeneid or Paradise Lost based on a single shared trait—that they take characters or worlds from other texts—risks eliding so much specificity as to strip the term "fan fiction" of almost all meaning. And yet, two special issues of Transformative Works and Cultures in 2016 and 2019, and two conferences in England in 2018 and 2019, as well as numerous individual panels and papers at other conferences, have been dedicated to exploring the possibilities of transhistorical analogies between fan fiction and premodern literature (note 4). So, what are we doing when we read premodern literature through fan fiction, or when we say that Dante's Inferno "is" fan fiction? How do we bring these two radically different literary fields together in a meaningful way?

2. Axis 1: Poaching

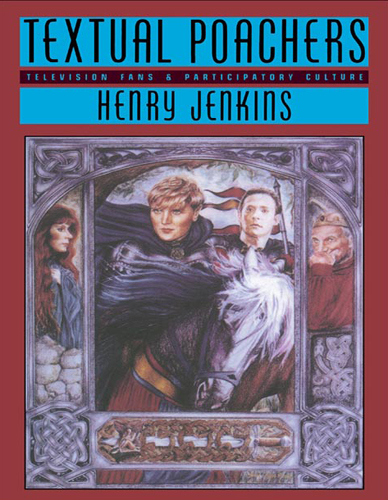

[2.1] Henry Jenkins's seminal book on fan fiction, Textual Poachers (1992), laid the ground for characterizing fan fiction primarily by its relationship to legal and social frameworks around the ownership of ideas. Camille Bacon-Smith's classic ethnography of fan fiction writers likewise opens, albeit flippantly, by portraying these fans as both "ladies of a literary society" and "terrorists" (1992, 4). The more recent definition of fan fiction as "transformative work," terminology drawing on language from the US legal system and popularized by the Organization of Transformative Works, reweights but does not substantially change Jenkins's "poaching" framework (Tushnet 2007). Since fan fiction's legal status has been perhaps the most important deciding factor in determining the shape of its distribution networks and communities, it is understandable that defining fan fiction, first and foremost, as unauthorized continues to be the most common approach. So, for example, Catherine Tosenberger's definition of fan fiction begins with its "recursivity" (its relationship to other texts) but further distinguishes fan fiction from other kinds of recursive literature following Jenkins's template: "Fan fiction is recursive literature that, whether out of preference or necessity, circulates outside of the 'official' institutional setting of commercial publishing" (2014, 16).

[2.2] This definition would seem of limited value for historians of premodern literature, situated as it is within a postcopyright legal system and late-stage capitalism, although it offers rich veins of inquiry for the emergence of the professional author, the amateur reader, and fan communities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, where these systems begin to emerge (Lynch 2015; Simonova 2012). However, Jenkins's central metaphor of poaching is rooted in the premodern. For Jenkins, fans resemble "the poachers of old" (1992, 26); fans hungry for media steal from large media conglomerates as hungry medieval peasants stole from landowners who hunted only for sport. In this metaphor, copyright is analogous to the medieval enclosure of the commons, a practice that restricted hunting and grazing rights to landowners, which in England began in around the thirteenth century CE and shaped the relationship of the people with the land well into the nineteenth century. The poaching metaphor evokes a heroic folk lineage including figures like Robin Hood (note 5) and situates fandom in a kind of Sherwood Forest, a marginal, unregulated, premodern space. The activity of fandom, in this metaphor, is the moral theft of texts and ideas from their wealthy owners and their return to a nostalgically imagined prior communality. Fans are decidedly not compared, in Jenkins's book, to modern-day poachers killing endangered big game for black market profit or illegally harvesting rare wild orchids—indeed, comparing these modern poachers to fan fiction writers would transfer the moral authority to the interpretive authorities and media owners against whom Jenkins's fans rebel. The book's original cover, a piece of fan art by Jean Kluge that depicts characters from Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987–94) in medieval costumes that evoke Arthuriana, prepares the reader for the implicit medieval setting of Jenkins's fan-poacher (figure 2).

Figure 2. Cover of Textual Poachers, featuring art by Jean Kluge (characters featured from Star Trek: The Next Generation are, from left, Beverley Crusher, Tasha Yar, Data, and Jean-Luc Picard).

[2.3] Jenkins's definition derives from de Certeau's (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life, where the premodern setting appears with even more suggestive force. De Certeau writes of the common reader: "Far from being writers—founders of their own place, heirs of the peasants of earlier ages now working on the soil of language, diggers of wells and builders of houses—readers are travellers; they move across lands belonging to someone else, like nomads poaching their way across fields they did not write, despoiling the wealth of Egypt to enjoy it themselves" (1984, 174). In the passages leading up to this section, De Certeau introduces a dizzying series of metaphors, in which the common reader is the traveler in the modern nation-state receiving a passport from interpretive authorities to enter the text in the correct way (171), then a trespasser on a "private hunting reserve" (171), then, in a strange role-reversal in this colonial fantasy, "a Robinson Crusoe discovering an island" (173), then a hunter in a forest (173), a modern-day Amazon or Ulysses (174), and finally, a "nomad" (174). De Certeau's temporal collapse makes his reader simultaneously a medieval Robin Hood resisting the dissolution of the English commons after the Norman conquest, an early modern settler colonist who imagines the lands she colonizes to be "premodern" (i.e., either not-yet-modern or not-yet-settled), and a "nomad," a figure evoking both indigenous populations of colonized states and persecuted nomadic European communities like the Roma. The premodern blurs into the postcolonial here in troubling and complex ways that Jenkins sidesteps through his partial excerpt of this quote (1992, 26). Jenkins does include de Certeau's final flourish, the allusion to the gold from Egypt, in which his common reader becomes St. Augustine's Christian reader of pagan classical texts. In On Christian Doctrine II.40, St. Augustine famously compares Christian readers of classical (pagan) philosophers to the Israelites who flee Egypt with the looted treasures of their former captors in Exodus 12 (note 6). This final allusion returns us to the premodern and to an early theory of reception that would legitimize medieval literary adaptation of classical sources.

[2.4] Tangled in the roots of Jenkins's poacher metaphor is the premodern past. Both Jenkins (implicitly) and de Certeau (explicitly) compare fans to premodern subjects who evaded, resisted, and occupied the margins of different interpretive authorities and institutional powers. Both connect the commons of fandom to the commons of premodern law, and both, to different degrees, situate their theorized reader in an imaginary, nostalgic premodernity. This association between the communal ownership of stories and the imagined premodern is built into the foundations of fan studies built on Jenkins's work, which itself drew on the self-understanding of the fan communities he studied.

[2.5] This is the axis of approach taken by most of the contributors to the 2019 Transformative Works and Cultures (TWC) special issue "Fan Fiction & Ancient Scribal Cultures," edited by Frauke Uhlenbruch and Sonja Ammann. As the editors write in their introduction, "fan studies provide excellent heuristic tools for exploring questions of textual authority and for foregrounding the role of the audience/fans in the production of texts and traditions" (2019, ¶ 1.2). The editors come to their transhistorical analogy through a different route than Jenkins: the influence of nineteenth-century biblical scholarship on early twentieth-century Sherlock Holmes fandom. In "Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes" (1999 [1911]), by Ronald A. Knox, a popular theologian and mystery novelist (perhaps now best known to mystery novel fans for his "Ten Commandments of Detective Fiction" [1929]), Knox applies the methods and terminology of scholarship on ancient literature, particularly biblical texts, to the Sherlock Holmes stories, to ridiculous effect. His paper enters into the fiction that Watson is the author of biographical sketches of a real detective. What are obviously small errors in consistency on the part of Doyle and his editors are treated as evidence of multiple authors, including "Deutero-Watson" and "proto-Watson," and a whole scholarly field is invented in a pastiche of German-style biblical textual criticism, together with German-sounding fictional scholars: "The 'Gloria Scott' is condemned by Backnecke partly on the ground of the statement that Holmes was only up for two years at College, while he speaks in the 'Musgrave Ritual' of 'my last years' at the University; which Backnecke supposes to prove that the two stories do not come from the same hand" (Knox 1999 [1911]).

[2.6] While obviously tongue in cheek, this piece was hailed in later years as the originator of a certain genre of fan criticism (Lellenberg 2011; Sveum and Lellenberg 2010). It was influential in two ways: its borrowing of terms from Christian biblical scholarship (so that the Holmes tales become the Sacred Writings) and its conceit that rather than being authored by Arthur Conan Doyle, the Sherlock Holmes writings were documents of true events, authored by John Watson, with Doyle relegated to a literary agent. The distinction between Doyleian and Watsonian readings—that is, between readings that acknowledge that one is reading a work of fiction and readings that enter into the fiction of the text to treat it as a true document of real events—has had long currency in some fan criticism circles. Another influential early fan-writer on Sherlock Holmes was Dorothy L. Sayers, whose training was in medieval literature and who would go on to translate Dante's Divine Comedy (in addition to her more famous mystery novels). A cofounder of two early Holmes fan societies in 1934, Sayers wrote several pieces of Sherlock Holmes fan criticism (meta) and what is arguably a piece of fan fiction wherein her own creation, Lord Peter Wimsey, meets Sherlock Holmes (Sayers 2001). The influence of methods from the study of premodern literature on Sherlock Holmes fandom, and from thence to other fandoms, thus came from several directions, the end result of which was a foundation for a kind of fan criticism that treats fan texts as premodern—that is, that participates in a shared, playful imagining that such texts exist outside of structures of copyright and the capitalist marketplace, and thus can be read through the heuristics developed to read premodern texts.

[2.7] In the "poaching" axis of approach, stories are understood primarily but not exclusively as property, so scholarship focuses on the relationships between texts and systems of ownership. This axis offers a useful lens for reading premodern literature with a focus on ownership, censorship, and questions of authority, authorship, influence, patronage, circulation, reception, cultural prestige, and hierarchies of canonicity that assign different values to different texts (and hence change the value attached to authoring or otherwise owning them). Several contributors to the 2019 "Fan Fiction and Ancient Scribal Cultures" issue of TWC argue that the concepts and terminology around authorship and canonicity that fan criticism has developed over the past hundred years, initially derived from biblical criticism, can in turn contribute to the study of early biblical canon formation (Amsler 2019a; Rosland 2019; Uhlenbruch and Ammann 2019) and to the study of reception and response in Midrashic literature and the Talmud (Amsler 2019b; Barenblat 2014, 2019). Applying fan approaches to historical texts requires some recalibration, and many of the articles in both the aforementioned special issue and TWC's 2016 special issue, "The Classical Canon and/as Transformative Work," edited by Ika Willis, tackle the problem of methodology. In her discussion of the relationship of translation to fan fiction, using translations of Homer as an example, Shannon Farley (2016) uses André Lefevre's concept of "systems" to describe the unique set of circumstances, influences, and pressures that shape any textual interpretation, including both translation and fan fiction. Ahuvia Kahane (2016) compares the process of canon formation in ancient Greek oral literary culture and in fan communities through a careful definition of terms in order not to efface but rather to highlight nuances of historical difference. Both Kahane's and Farley's articles use fan fiction to discuss process and relationality; the poaching axis lends itself to analyses such as these of where, how, and why interpretation, rewriting, and adaptation happens, or any process in which there is a negotiation of interpretive authority. The second axis of approach—transformation—lends itself more to analysis of the texts that result from these processes, to the aesthetics of transformative literature.

3. Axis 2: Transformation

[3.1] The comparisons in the popular press between fan fiction and the Aeneid, Hamlet, Paradise Lost, and other premodern texts are often made on the basis of fan fiction's formal properties, as literature which rewrites, adapts, extends, borrows from, or interpolates other literature. Catherine Tosenberger (2014), following David Langford, calls this type of literature "recursive" (an alternative term to "transformative" or to Abigail Derecho's [2006] proposal, "archontic," which I will discuss below) (note 8). Tosenberger (2014, 14) points out that while fan fiction has been compared to both premodern literature and to folk tales and oral traditions, she prefers the former as a model, because premodern literature aesthetically values recursivity, while recursivity is baked into form of folklore:

[3.2] Because "repetition" is built into the very concept of the category, folk narratives do not need to be explicitly marked the way that recursive literary texts do, since the latter battle with the Romantic conception of originality as a marker of aesthetic quality. Indeed, the Romantic conception of folklore is in direct opposition to the Romantic conception of art; folk narratives were constructed as valuable precisely because of their lack of originality—that is, their status as presumed survivals from an earlier age. These separate hierarchies of value were used to downplay or denigrate recursivity in literature (as unoriginal) and innovation in folk narrative (as inauthentic).

[3.3] Tosenberger's (2014, 14) explanatory examples for recursive literature include several familiar premodern texts: "Paradise Lost, much of the Arthurian corpus, many of Shakespeare's plays, Ulysses, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, Wide Sargasso Sea, and so on." Because she focuses on transformation's artistic characteristics, Tosenberger distinguishes folklore from recursive literature. But many comparisons between fan fiction and premodern literature that use poaching as their axis of approach often collapse together folklore and myth with recursive literature, because they are foregrounding the concept of an imaginative commons. In the discourse that Ika Willis (2016, ¶ 2.2–4) analyses, "the use of the term myth…specifically invokes a folkloric model linked to a particular understanding of intellectual and cultural property…One of the key functions of the appeal to myth (or legend) here is to refuse or deny one of the most obvious differences between ancient myth and contemporary mass culture: the economic conditions of its production and circulation. Unlike Robin Hood and Odysseus, Han Solo is trademarked; his name and likeness are the intellectual property of Lucasfilm." In some ways, it is crudely artificial to distinguish intertextuality in premodern literature as a moral or legal category from intertextuality as an artistic mode, since these distinctions are themselves rooted in twenty-first-century law, ethics, and art. Be that as it may, for fan fiction studies, arguments that treat premodern literature as a literature that treats ideas and texts as communal are often distinct from arguments that treat premodern literature as a literature that values transformation. It is this second axis of approach with which I am now concerned and that I will call transformation.

[3.4] In the name "The Organization for Transformative Works," the term "transformative" asserts that fan fiction occupies a legal category of artistic works (including, for example, parody, or reviews that quote the original work) that have sufficiently transformed another property as to not be in violation of copyright (Tushnet 2007, 61). However, fans and fan scholars often also use the term "transformative" in place of counter-terms like "appropriative" or "derivative," where the operative discourse is not legal or even moral but aesthetic. Here, the term "transformative" serves to argue that originality is not the be-all and end-all of artistic practice, as well as that fan fiction as art—legal considerations aside—does not necessarily occupy a place below its source in a cultural or artistic hierarchy. These analyses focus on the formal and narrative elements of fan fiction—the ways in which it transforms its source and to what effect. Analyses that define fan fiction as first and foremost transformative also often favor expansive definitions of fan fiction that include modern published fiction that transforms source texts whose copyright has expired. Such texts share some formal qualities with fan fiction but were not created within fan communities; Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead and Wide Sargasso Sea are probably the most frequently given examples (see, e.g., Pugh 2004, 194–95).

[3.5] Abigail Derecho's influential 2006 article "Archontic Literature: A Definition, A History, and Several Theories of Fan Fiction" offers "archontic" (from "archive") as a useful term for theorizing fan fiction. This term proposes a different relationship between source and fan fiction than cultural, artistic, or even temporal primacy. Following the Derridean concept of the virtual archive, within the archontic model, all texts are unstable, containing limitless potentialities (Derecho 2006, 75). Fan fiction of Pride and Prejudice, in this model, shares a virtual archive with all the different printings and editions of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice, the various Pride and Prejudice television adaptations, translations of Pride and Prejudice into other languages, P. D. James's 2011 novel Death Comes To Pemberley, Seth Grahame-Smith's 2009 novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, the 2008 television series Lost in Austin, and even more fragmentary artifacts like gifs of Colin Firth emerging from a pond in a clinging white shirt, cloth shopping bags depicting a dustjacket of Pride and Prejudice, and so on. The usefulness of this term lies in its radical dehierarchizing of the relationship between fan fiction and its source text, an important precursor for critical analysis; unlike "transformative," "archontic" also articulates fan fiction's relationship with other paratexts. Tosenberger (2014, 15) argues that "recursive" "marks a specific, and active, relationship between texts," and so prefers it to "archontic," which she sees as a more passive descriptor: "'archontic' refers to a space; 'recursive' refers to an action." I have chosen "transformative" for this axis less out of preference for it as a term and more because it is more widely used than either "recursive" or "archontic," both of which overlap significantly with "transformative" in meaning.

[3.6] What may seem like haggling over terminology here points to the very reason why analogies between fan fiction and premodern literature have the potential to be so productive—because attention to how and why we might compare them forces us to rescrutinize what, precisely, a text, genre, or a literature is, and what makes it so. For example, fan fiction troubles the reader/writer binary, drawing attention to the ways in which readers collectively reauthor texts through marginal annotation and commentary, textual editing, translation, and other interpretive acts. Fan fiction's authorial indeterminacy—which is actually a failure to fit into categories of authorship shaped by the marketplace—demands reexamination of what we mean by authorship in a way that is particularly productive for premodern texts, where authorship is often collective and highly complex. All three of these competing and overlapping terms for what fan fiction is—recursive, archontic, transformative—direct attention to the literary techniques around which fan fiction communities have developed huge and highly specific taxonomies. Take, for example, the range of microgenres within fan fiction, such as "curtainfic," which names a story with domestic details and a comforting affect, in which characters from the source text, usually in a happy relationship, do domestic tasks, often centered around cultivating their shared space, such as shopping for curtains ("Curtainfic" n.d.), or the seven main types and more than thirty-five subtypes of "alternate universe" fan fiction named on the Fanlore wiki page ("Alternate Universe," n.d.). This taxonomy is literary theory: it is the product of decades of communal debate about how specific kinds of narrative work and how the foot traffic of fan readers creates desired paths through source texts. Genre here emerges from the ways in which readers respond to preexisting texts or storyworlds rather than from publishing categories or cultural technologies like literary prizes, offering a helpful way to approach the highly problematic subject of genre in premodern texts.

[3.7] Parrish's web comic draws on the literary theory of fandom for its reading of Dante. It implicitly reads Dante's Divine Comedy as fan fiction not only because of broadly shared transformative qualities but as a specific kind of transformation that has a name and a body of scholarship within fandom but not outside it: Mary Sue fic (Busse 2016). For the knowledgeable fan reader, the comic invokes the Mary Sue as a heuristic tool with which to gather for discussion the aesthetics, ethics, cultural valences, and narrative repercussions of Dante's appearance in his own work as a character in a relationship with a celebrated author of whom he is a fan. What happens when we imagine Dante into the debased, gendered position of a fan? What happens to the Divine Comedy if we read it through the lens of the Mary Sue? In an as-yet unpublished paper, Ika Willis (2010, 17) does just this, placing both Dante and the Mary Sue in conversation with Barthes, arguing that the relationship between Dante and Virgil thinks through "the reorganization of the text according to the reader's desire, and, especially, the production of a space of address between the text and the reader which addresses the reader as unsubstitutable, unique subject."

[3.8] The transformative axis of approach is productive with premodern literary texts that circulate in conversation with other adaptations of the same source, such as medieval romances. For example, Angela Florscheutz's (2019, 11) article on the fourteenth-century Middle English romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight argues that the poem "invites attention to its own status as a work of archontic literature, or literature that draws and builds upon previously existing textual worlds and that allows for unlimited expansions to the textual conglomeration or archive." She argues that the poem gains much of its literary effect and humor from its refusal to conform to its contemporary audience's expectations of Gawain and stories about Gawain. In this reading, characters in the poem ventriloquize the fans of Gawain poems, who make up the audience, and likewise voice their disappointment and chagrin when he does not perform. Ultimately, Florscheutz uses the comparison with fan fiction to unpack the poem's playful exploration of interpretive authority. The fan fiction lens guides analysis not only of the poem's transformation of its sources, but its interest in the friction between the Gawain fans—such as Lady Bertilak, who accuses the unexpectedly prudish Gawain, "þat 3e be gawan hit gotz in mynde" (l. 1293; I suspect you of not being Gawain)—and Gawain's struggle to adhere to his own moral code.

[3.9] Analysis of fan fiction as a literary genre has most often gravitated toward fan fiction that extends the pleasures of the source text by resisting and challenging it. Through fan fiction, Ika Willis (2006, 155) writes, the reader can "make space for her own desires in a text which may not at first provide the resources to sustain them." Much fan fiction is dedicated to imagining same-sex romances between main characters who are depicted in the source text as straight and cis, drawing out queer valences in traditionally homosocial but heteronormative media genres like police procedurals. Lothian, Busse, and Reid in 2007 posited "slash fandom" (note 9) as a "queer female space," an argument taken up by De Kosnik in her discussions of fan fiction archives (2016, 145–53; Busse 2006; Lothian, Busse, and Reid 2007). "Queer" here is a capacious category going beyond a specific sexual orientation or identity, functioning more as a shorthand for the proliferation of marginalized desires, identities, and bodies that fan fiction reads into source texts. What Alexis Lothian has called "critical fandom" uses creative transformation to recenter voices, perspectives, or identities at the edges of the source text, or by reimagining the voices at its center (Lothian 2018). For example, andré m. carrington (2016, 197) analyses fan fiction that centers minor (in terms of narrative space and screen time) Black characters in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997–2003) and Harry Potter (1997–), arguing that these fan works "dislodge tropes of fantasy from a British cultural frame of reference that is presumptively identical to Whiteness," while Jonathan A. Rose (2020, 28) argues that fan fiction for the BBC show Sherlock (2010–17) that imagines the character of John Watson as a trans man draws attention to trans embodiment and so "destabilizes cisnormative readings of popular culture."

[3.10] Approaches to premodern literature that foreground the narrative aspects of fan fiction often use the critical tools developed in fan fiction communities and fan studies to reclaim voices from the margins—sometimes the literal margins, as in Kavita Mudan Finn's (2017) reading of early modern paratexts and the Archive of Our Own. E. J. Nielsen's (2017) reading of Christine de Pizan's early fifteenth-century Book of the City of the Ladies applies tools from the study of fan fiction to Christine's critique of misogynist historiography, while Balaka Basu (2016) draws out the queer valences of Sir Philip Sydney's Arcadia as fan fiction. Finn and McCall (2016, 34), in their discussion of modern fan fiction of Shakespeare, argue that the extrainstitutional, extracanonical spaces in which fan fiction circulates open up spaces for "creative misreadings," wherein fandom's norms of interpretive play make possible critical pathways that the norms of critical scholarship do not (see also Fazel and Geddes 2016).

[3.11] Critiques by scholars whose work intersects with critical race theory have introduced important critiques of how fan studies scholarship, and particularly analysis along the axis of transformation, has often failed to be intersectional. These scholars note that while fan fiction's transformative readings may resist or subvert their source text's representation of gender and sexuality, they may affirm ideologies of normative whiteness (Pande 2018; Stanfill 2011; Wanzo 2015; Woo 2018). Positioning the fan as marginal within a cultural hierarchy, Pande (2018, 28) writes, "is increasingly leading to arguments that maintain that the very act of identifying as a fan somehow makes white cisgender women participants in these spaces less privileged on an institutional level, or less culpable for holding and perpetuating ideas rooted in racism." The tendency to imagine fandom as always transformative and transformation as always liberatory has had a limiting effect on premodern fan fiction studies, making it difficult, for example, to imagine using fan fiction paradigms in relation to complex and troubling literature like English religious drama. Texts like the York Cycle crucifixion pageant transform the text of the Gospels into community theatre, empowering local actors to inhabit, explore, and even subvert biblical scriptures while also constituting their audience as a Christian polity in part by means of ritualized antisemitism. The critiques of Pande (2018), Stanfill (2011), Wanzo (2015), Woo (2018), and others draw a crucial distinction between unauthorized reading and resistive reading. They challenge us to refine fan fiction-based approaches to premodern literatures with intersectional analyses that acknowledge multiple axes of marginalization and cultural authority. This challenge can also shape an approach to texts that explore a minoritized reading position and yet also reaffirm hegemonic orthodoxies, as I will describe in the next section.

[3.12] Pande's (2018) critique also highlights how transformative fan fiction and its scholarship has been embedded in a politics of affect that affirms the circulation of pleasure and desire between women fans whose whiteness is presumed. Disrupting that presumption interrupts the circulation of pleasure. Pande (2018, 13) draws on Sarah Ahmed's model of the feminist killjoy to theorize "what it means to be a fandom killjoy—that is, for one's pleasure to threaten the invocation of a woman-centric, and queer-coded community." Nicholas-Brie Guarriello (2019, ¶ 5.16) argues that "Coliver" fan fiction for the show How to Get Away with Murder (2014–20) "reaffirm[s] a neoliberal mandate for happiness," as the affective economies of fandom incentivize authors to produce frictionless, "fluffy" romance stories about this queer interracial couple that effectively erase any discussion of race or cultural difference that might raise specters of discomfort, thus reinforcing normative whiteness. Building on earlier, critical race theory–informed critiques of fandom, fan fiction, and fan studies, Guarriello's (2019) analysis disrupts the assumption of a universalized fan reader (imagined by default to be white, female, and, often, heterosexual) in transformative rewritings that focus on bodies and embodiment. It also shows how the affective politics of fandom shapes the transformative work fan fiction can do.

[3.13] These questions provoke attention to how our own investment as critics in transformative fan fiction as liberatory may unduly influence which medieval texts we feel comfortable calling fan fiction. More, Guarriello's (2019) critique marks a point of intersection between the transformative axis of approach to fan fiction and the final axis I will discuss: affect. This approach focuses on reader positionality and the kinds of reading communities within which fan fiction is embedded.

4. Axis 3: Affect

[4.1] While embedded in an almost wholly digital landscape, modern fan fiction is a literature of embodied experiences, both those of the fictional characters and those of the authors, who cultivate somatic responses like tears or arousal in their readers. Authors also often explicitly use fan fiction to process, narrativize, and explore their own experiences of gender transition, disability, sexuality, and trauma. Fan fiction emerges from and is circulated within reading communities that are passionately and intimately involved with their source texts, communities for whom deep familiarity with a text cannot be easily separated from practices of self-fashioning or from ties of friendship, love, and animosity with other fans or with source text creators, fictional characters, actors, and other celebrities (note 10). The affective reading practices common in fandom and of the romance genre more generally are heavily gendered as feminine, and many of the fan communities that produce fan fiction—those attached to popular music groups, television and movie celebrities, and novels with romantic content—are historically associated with young women, as in iconic images such as the screaming crowds of girls at Beatles concerts (Ehrenreich, Hess, and Jacobs 1992; Huyssen 1986; Lahti and Nash 1999). The original Mary Sue, in Paula Smith's 1973 parody of self-insert Star Trek fan fiction, proudly proclaims that she is "fifteen and a half years old" (Walker 2011); this most quintessential fan fiction trope is indelibly associated with inept teenage girl fan writers in part because of Smith's satire. Fan fiction, therefore, is not only gendered as a literary form, but also aged. It is associated with an immature emotional life—with immoderate passion, unrequited crushes, a preference for fantasy over reality, and inappropriate or transitional object choices for one's desires outside of the heteropatriarchal structures of adult reproduction.

[4.2] Fannishness is, in this sense, a queer mode that both resides in and generates around itself a queer temporality: rhythms of life that are at odds with the linear progress of heteronormative life-paths and with full (adult) participation in capitalist society (Dinshaw 1999, 2012; Edelman 2004; Freeman 2010; Halberstam 2005). Fannishness's queerness is inseparable from the fact that the great majority of fan fiction readers and writers identify outside of cis masculinity or heterosexuality and are young, in their teens or early twenties (see note 1), and that much fan fiction deals with same-sex romance. The heavy identification of fan fiction with feminine or feminizing reading practices, marginalized gender expressions and sexual identities, and immaturity or youngness represents a significant divergence from the now-familiar list of high culture texts by Virgil, Shakespeare, Milton, Joyce, and so on. In Parrish's reimagining, the fan and fan fiction are interconnected: Dante's fantasy about Virgil becomes a teenage girl's fantasy, signified by visual markers like the florid cursive and the pale pink bedroom, as well as the interaction with his mother, which reveals an infantilizing living situation. It is not only the Inferno's form that makes it fan fiction but also Dante's desire for intimacy with the long-dead poet Virgil, a desire which is queer in that it is same-sex but also queer in its temporality. Reading Dante as a Mary Sue author, here, opens up questions about the circumstances of the Inferno's composition, the community in which it circulated, the importance of parasocial relationships in early humanist circles, and even the invisibility of women's labor in the single-author model (who made Dante's meals?).

[4.3] The affect axis of approach, therefore, primarily defines fan fiction not by its relationship to copyright or authorial ownership, nor by its formal elements of adaptation, but by its production within a community oriented around shared affects. This community occupies a position outside of heteronormative masculinity through its affective mode, which is related to but not identical with its demographic makeup. The affect axis of approach to premodern fan fiction might direct attention toward, for example, the circulation of texts as objects of exchange or gifts within an exclusive reading community, the materiality of such texts as objects of care, the structures of feeling within and around texts, or the self-fashioning of members of a particular reading community around their textual affiliations. It also particularly directs attention toward the history of women's reading, to historic queer and other marginalized communities, and to the complex intertwinings of identity and reading through history.

[4.4] Paradoxically, therefore, scholarship in fan studies that is most interested in fan fiction as a historically and technologically situated literature (e.g., in zines, digital archives, online gift exchanges, or social media platforms) can offer better models for some kinds of premodern fannish reading than studies of fan fiction that follow the axes of poaching or transformation, as they offer theorizations of fan fiction, first and foremost, as a literature of affective communities (note 11). Because this third axis privileges affect, both public and private, it directs the gaze toward readers' bodies. Here, of course, it overlaps with other approaches to fan fiction: the first axis (poaching) can lead to a focus on reading communities via its attentiveness to social institutions and cultural hierarchies, and the second axis (transformation) can also lead to a focus on readers via its interest in fan fiction as space in which to recenter identities and voices marginalized in mainstream media texts. However, the third axis (affect) places fan reading communities and their reading practices and hermeneutics at the center of analysis.

[4.5] I have argued elsewhere that fan fiction is a kind of affective reception—"reception organized around feeling" (Wilson 2016a, ¶ 1.2)—and have compared it with, among other medieval literatures, a genre of English Christian devotional literature of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries that guides its readers (often women) to imagine themselves as characters in the Gospels and to fill in missing scenes in biblical narrative. Devotional guides like Nicholas Love's Mirror of the Blessed Life of Christ and the text on which it is based, the Pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditations on the Life of Christ (Meditationes vitae Christi), Aelred of Rievaulx's Rule of Life for a Recluse (De institutione inclusarum), the anonymous Ancrene Wisse, and accounts of the lives of religious women, like the writings of Bridget of Sweden and The Book of Margery Kempe, not only transform biblical narrative but also theorize this process of creative transformation as a devotional act that is itself gendered and also placed low on a cultural hierarchy. Reading these texts as fan fiction allows us to focus on the ways these texts teach transformative literary techniques—that is, they teach their readers how to mentally compose their own fan fiction, within certain bounds that uneasily coexist with ecclesiastical authority. These literary techniques are associated with women's spirituality, but they also open a space for cross-identification and gender fluidity by readers of all genders. Within this historically situated reading community, composing and reading such fan fiction, which is designed specifically to concentrate the reader's intense feelings of empathy, love, and grief at different stages of Christ's passion, becomes an act of religious devotion (Wilson 2015, 2016b).

[4.6] Fan fiction, fandom discourse, and community-authored fan fiction distribution infrastructures offer theorizations of the pleasures and pains of using and loving texts. Some premodern literature may resist this kind of analysis, particularly where few traces remain of the communities within which it circulated or where little is known of the circumstances of its creation and early reception. However, while analyses focused on readers and reading communities often situate a text in a specific time and place, it need not be the moment of the text's creation; a reading of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as fan fiction along these lines, for example, might, like Angela Florscheutz's (2019) article, focus on the text's depiction of its own fan communities or read it as both participating in and generative of fan fiction and fan art in the context of the pre-Raphaelite artistic and literary movement of the nineteenth century.

[4.7] In addition, this approach can open up ways to read premodern literature whose transformative properties are not often considered particularly interesting—because they are rote, or artistically negligible, or tritely orthodox—but that offer a glimpse into rich cultures of affective reading. For example, Dot Porter's (2019) reading of Books of Hours—medieval Christian prayerbooks—argues that each unique manuscript, often designed to a patron's specifications and containing marginal annotations by generations of readers, is its own transformative work. Books of Hours are more often treated by scholars of the medieval world as beautiful objects than as works of literature; Porter suggests that by reading them through the lens of fan fiction as affective reception, we might reframe the conversation around Books of Hours using a "language of care," combining study of the books themselves as material objects that were read and loved, and study of the religious affect that the texts in the book fostered and nourished through their transformation of monastic liturgy for everyday use by the laity. Her work agrees here with Frauke Uhlenbruch and Sonja Ammann (2019, ¶ 3.11) in their editorial for their special issue of TWC on fan fiction and ancient scribal cultures: "We should…avoid unhelpful assumptions such as the idea that 'authoritative' means 'untouchable.' To love a text and to take it seriously have always meant to use it."

[4.8] When we read fan fiction as literature emerging from a discourse that privileges affect, studies of premodern fan fiction may become studies of premodern squee, premodern obsession, premodern antifandom, or premodern "fandom killjoys." Here, study of premodern fan fiction might engage with the robust work done on premodern audiences and celebrity, from late antique chariot racing (Cameron 1976) to the Tudor stage (Cerasano 2005), and on the history of the emotions (Reddy 2001; Rosenwein 2015). Furthermore, when we approach fan fiction as part of a constellation of ways to love a text—as, perhaps, a literature of desire—fan fiction more obviously takes its place among other histories of desire, of desire's performances, modes, and identities.

5. Conclusion: The present

[5.1] The three axes of approach I have laid out suggest a possible theoretical model for an interdisciplinary premodern fan fiction studies. They also offer an answer to the question with which I began—"Is Dante's Inferno fan fiction?"—although that answer is, in typically annoying academic fashion, also a question: "What do you mean by fan fiction?" Fan fiction is a literary genre, a form, a legal category, an affective community, an aesthetic, an economy, and more, and each of its aspects demands a different approach. For this reason, attempts to create a premodern fan fiction studies by first identifying a canon of premodern fan fiction texts are misguided; the next steps for the development of this burgeoning and vibrant field of study must be in the development of its methodology.

[5.2] As the scholarship I've reviewed in this article shows, premodern fan fiction studies is well positioned to contribute to larger conversations across disciplines about power, canonicity, marginality, institutions, structural inequalities, and affect in the study of literature. Participation in such conversations must include, first and foremost, reflection on how these issues are playing out in our own research projects, and so I move finally and briefly from the domain of conceptual methodologies to practical methodologies and the ethics of research. Across the three paradigms for research that I have discussed, the strength and novelty of premodern fan fiction studies comes from the juxtaposition of two historical moments, literatures, communities, and bodies of scholarship. These bodies of scholarship also represent disciplinary socialization; premodern fan fiction scholars often have premodern literature or history as home disciplines. These disciplines do not, generally speaking, work with living subjects in their research. Fan fiction often serves as a space to explore sensitive and intimate topics, and fan authors are often minors and/or vulnerable through belonging to one or more minority groups. For interdisciplinary scholars of premodern fan fiction studies, professional success may mean influencing the adoption of fan fiction paradigms by other scholars in their discipline who are not themselves members of a fan community. What kinds of ethics, then, do we have a responsibility to communicate along with these paradigms? A premodern fan fiction studies must include consultation of the emerging best practices around the ethics of fan studies research (Busse and Hellekson 2012; Freund and Fielding 2013; Howell 2016; Jansen 2020; Jones 2016; Kustritz 2018). In all premodern disciplines, it is increasingly urgently clear that the study of the past must include the interrogation of our own responsibility toward the present; the study of fan fiction is no exception to this rule.