1. Introduction

[1.1] The question of ethical methodologies in the field of fan studies is nearly as old as the field itself: Jenkins (2013), for example, has long called for practices that privilege transparency and open lines of communication between academics (and acafans) and the fan groups they study. Indeed, for a field that is often structured by a broad scope of practices and interdisciplinary methodologies (Largent, Popova, and Vist 2020) and a general sense that ethical parameters will be shaped on a case-by-case basis (Deller 2018), over the years there have developed a few points of consensus about ethical research practices in fan studies: to treat fan communities with the utmost respect, to do no harm, and to share research findings with the community (Brooker, Duffett, and Hellekson 2017; Deller 2018; Dym and Fiesler 2020; Kelley 2016). This last condition—to share the research, to make it accessible, and to give the community an opportunity to correct or give feedback—raises some interesting methodological questions about how we put this into practice. Some scholars have framed such an activity as a way to "give back" to the community (Dym and Fiesler 2020 ¶ 5.20)—that is, to contribute to the community so that "the researcher is not merely taking information out without giving anything to the community in return" (Cristofari and Guitton 2017, 727). To use research to give back, however, is a proposition that frames research in terms of a gift economy. Can sharing the research be a way to give back? And if so, how might that be done?

[1.2] Over the course of a two-year study, I put these questions to the test and devised a range of text-based and creative (or play-based) practices for sharing research that could be trialed during and after a study of a fan community to which I belonged. The fan group in question was an adult fan of Lego (AFOL) community based in Perth, Western Australia: the Perth Lego Users Group (Perth LUG). The study sought to understand the participatory behaviors of the community both online on our community Facebook page and off-line at our monthly face-to-face meetings (Build Nights) where members gather to socialize and to build with Lego. Data was collected through both interviewing members and analyzing their online activities. By way of sharing the findings of this quantitative and qualitative research and analysis, I offered the community a text-based summary of the findings (a report) as well as a range of custom-built Lego models (in the Lego community called "MOCs" or "My Own Creations") that sought to capture the data and the research process. In sharing these findings in these forms, I sought to determine their relative strengths and weaknesses as mechanisms to give back to community and to evaluate whether the community was more likely to engage with play-based than text-based forms and whether research participants demonstrated more interest than the general fan community in the findings. As I detail in the following pages, the results of these experiments offer some insights into the distinct affordances of capturing and sharing research in creative forms, but also the importance of making both nonacademic and academic accounts of the research available to fan communities. While both creative and text-based forms were, ultimately, successful in sharing the research and engaging the community in the study's findings, it was the creative practice that seemed to capture the spirit of giving back by making a contribution to the community using their own modes of community participation and by drawing me further into the community and their practices.

2. Declarations of acafandom

[2.1] Before we ask the question, "How might I give back to the fan community I have studied (or will study)?" I think it is first crucial to answer the question, "Am I part of this fan community?" To recognize and claim the position of an acafan—one who claims allegiance to and thus a different kind of understanding of, access to, and authority in explaining the culture or community (Brooker, Duffett, and Hellekson 2017)—is to take on a different and, perhaps, considerably more complicated ethical negotiation about one's identity and power than the scholar who does not claim such an allegiance. The acafan signals a "dual allegiance" (Jenkins 2011) to both scholarly and fannish worlds but also a kind of dual identity as an academic and a fan, a subjectivity that will function differently in each world. To declare oneself a fan or acafan in scholarly contexts can be an assertion of authority, as Raw (2020) has noted in her study of the rhetoric of self-identifying as a fan. In fannish contexts, such a declaration might do very different kinds of work: it can foster relationships with other fans by signaling one's commitment to the culture under study (to be an insider rather than outsider), but it can also make fan communities wary that they and their practices will be misrepresented, misunderstood, or circulated outside of the original contexts and intended audiences (Raw 2020).

[2.2] There has been much scholarly debate about the power, effects, and practices of acafandom (see, for example, the 2020 "Fan Studies Methodologies" issue [vol. 33] of Transformative Works and Cultures) but it is of particular concern to us here because it can influence what might be an appropriate way to share research and what one might give back to the community. As academics, we can draw upon our existing knowledge and practices for disseminating research (oral presentations, slideshows, reports, and other text-based documents) without appropriating fan practices. Presenting one's research to the fan community in these ways emphasizes the "aca" of our acafandom and the authority and power embedded in that position, with its forms and discourses. Presenting research to the fan community in a way that emphasizes the "fan" and fan practices can take a broad range of forms, and while such activities might run the risk of misrepresenting or misappropriating fan activities, that risk is presumably higher for the academic who is not an acafan. Even if an academic strives (as they should) to understand the community norms (Dym and Fiesler 2020), this does not necessarily mean they can or should reproduce those norms: it is not hard to imagine the kinds of cringeworthy albeit well-meaning attempts to mimic fan practices that might result. On the other hand, a community might very much welcome an academic outsider attempting to embrace the culture. As is so often advised, these considerations must be taken not only carefully and with deference to the community but also on a case-by-case basis. However, to be an acafan does open up more possibilities of disseminating research and giving back to the community in forms beyond the purview of conventional academic practices.

[2.3] It is important then that I self-consciously self-identify as an acafan in this study. To both academic audiences and to the fan community, I have made this identity visible and explicit, although not always using discourses of acafandom. In recruiting participants from the Perth LUG for my study, I used both online and off-line community spaces to do so: the Facebook page and the off-line Build Nights. My recruitment poster (figure 1) sought to balance both aspects of my identity by signaling my Lego fandom by using a minifigure avatar (a common AFOL practice), offering a link to my fan activities on Instagram, and self-identifying as a "Lego Fan and [then] Academic" and by signaling my academic credentials through my professional designation, my institutional email address, and my authority through the university's research ethics committee. The distribution of this poster at face-to-face Build Nights also helped to signal my participation in the community. The online recruitment done through a recruitment blurb posted on the Perth LUG Facebook page was not explicit about my participation in the AFOL community: my belonging was only implied through my membership (only members may post on the page) and through what the members may have recalled of my previous online activity with the group (note 1). Neither recruitment technique, however, guaranteed that participants understood or recognized me as part of the community; during the interviews, one participant recruited from the Build Night encouraged me to join the group (and was surprised to learn I was already a member) and another participant recruited online referred to me as someone outside the group who seeks to understand the group.

Figure 1. Recruitment poster.

[2.4] To audiences in academic spaces, my position as an acafan researcher of Lego was made explicit through discourses of acafandom where I self-identified as an acafan and incorporated elements of my fandom into my presentations (distributing Lego for audience members to play with and using images of and links to my Lego activities in the PowerPoint slides). What was less clear to both fan and academic communities was that the research project was prompted by my fan interests rather than by my areas of research expertise—celebrity, identity performance, and life writing. Although I was interested in fandom as an element of celebrity culture and had taught aspects of fan studies, I had neither formal training nor publications in the field in general or in Lego in particular. Thus while I am still an acafan (and not, in Hills's formulation, a "fan-academic" who "uses academic theorising within their fan writing and within the construction of a scholarly fan identity" [2002, 16]), my work on this project felt motivated by fandom but rationalized by academia. It is also worth acknowledging that I have benefited as both a fan and an academic through this project: not only have I become more visible in the AFOL and Perth LUG communities and developed more extensive networks and friendships among the community members but I have also been able to turn this research into conference papers, publications, and lecture materials and raise my visibility as a researcher with strong community ties among my colleagues.

3. What does it mean to give back?

[3.1] I have gained much—as acafans usually do when they get to study their sites of fandom—and this condition raises certain ethical considerations about how acafans (and academics in general) can, in turn, be of benefit or use to the communities they study. What can we give back into the community so that they too gain something? We know, of course, of the importance of sharing our research with the community and soliciting feedback from them regarding that research (Dym and Fiesler 2020; Kelley 2016; Jenkins 2013). While this is good practice, is it actually useful or even interesting to the community? Will a community benefit from knowing, for example, what are the rates of online participation? Or which months, days of the week, or time or date are the most popular for posting? (note 2). Dym and Fiesler (2020) have suggested that sharing research is a way to give back to the community, but this would, I believe, depend a great deal not just on what we propose to offer them by way of information but also how—that is, what form that information will take. To give back, I would argue, is more than simply a matter of taking what we took out of or from the community (such as information about fan practices), repackaging it, and giving it back in a new form; it is a matter of giving—that is, to provide, to contribute, to present something that was not already theirs but something we have created for them. Such an exchange fits naturally within what Hellekson (2009, 114) has described as the "gift economy" of fan cultures where exchange between fans is predicated not on a commercial economy of gain but on a gift economy of exchange where one gives, receives, and reciprocates.

[3.2] To give back to the community is thus to participate in the fan community's gift economy and to reciprocate the hospitality from which we have gained. As Cristofari and Guitton have observed in their study of acafandom, "contributing to the community studied might be an ethical way to avoid cultural appropriation, by making sure the researcher is not merely taking information without giving anything to the community in return" (2017, 727). The discourses of giving "in return" that Cristofari and Guitton invoke here are instructive—there is something reciprocal in the exchange, and the community stands to benefit in return: there is a contribution to be made. It is for this reason that we should not always assume that our research, neatly packaged in a report or infographic, can meet these obligations unless we have given serious consideration to what the community stands to gain.

4. Academic and fannish gifts

[4.1] In the spirit of keeping the community's needs, interests, and activities in mind, my study of the Perth Lego Users Group's online and off-line participatory activities sought to find innovative ways to turn my research findings into a gift of sorts. As a self-declared acafan, it seemed fitting to experiment with both academic and fannish gifts, as neither would risk appropriating cultures or cultural forms I was not already familiar with. However, there was a distinct absence of examples or methodologies for this in the scholarly literature save vague allusions to sharing research through reports or offering transcripts of interviews. Without precedents to guide me, I made my own choices (and assumptions) about what forms would be appropriate, useful, and feasible. For the academic gift, a report seemed a fitting and appropriate form. Reports, I reasoned, can convey substantial amounts of data in accessible, reader-friendly formats and have the advantage of being easily shared. My fannish gift, on the other hand, sought to tap into the cultures of creativity at the heart of Lego fandom and the value that AFOLs place on custom designs. As such, I planned to design several MOCs that could capture different aspects of the qualitative and quantitative research data and could be photographed and shared on the community's Facebook page.

[4.2] My academic gift of a text-based report with a handful of infographics offered a significant amount of data in a fairly conventional and accessible format (see Lee 2020). This sixteen-page document included a summary of findings that may have been interesting but, perhaps, not terribly useful to members (e.g., age and gender participation rates or trends in online activities), but it also strategically included material specifically solicited to help the community. In my interviews, for example, I asked participants to share their thoughts on what they might like to see changed about how the administrators of the group ran the off-line events and online Facebook page with the understanding that this feedback was to be given to the administrators. I also asked participants about the obstacles they might face in their participatory activities that might be addressed by administrators in order to make participation online and off-line more accessible. My intent was to give members an opportunity to anonymously voice any concerns or suggestions that they thought would serve themselves or the community better. Their answers to these questions were made available in the report wherein I identified trends in their answers and also provided appendices where every anonymized answer was listed verbatim.

[4.3] While an accessible but still relatively academic form of sharing research, this report was an attempt to be a voice for the membership and a mechanism for community moderators or administrators to better understand the needs of the membership. In this way, then, a report can potentially function as a way to give back and contribute something to the community. It's important to note as well that during the interview process, it became even more evident how crucial it was to feed the results of the study back into the community. When I asked participants at the conclusion of the interview why they agreed to participate in this study, the overwhelming response was that participating in this project gave them an opportunity to "help the community" (Participant C), "give back" (Participant F), and "make things better" (Participant K) (note 3). There was an anticipation and expectation that the results of the study could be used for the benefit of the group, a keen reminder to researchers that participants may indeed have expectations of us to contribute and reciprocate.

[4.4] These sentiments that expressed the members' own participation in the giving and receiving dynamic of the community were indicative of the culture of the group and the patterns of participatory behavior that the study uncovered. An analysis of ten members' online activities over the course of a year determined that Facebook activity was characterized by contributions that engaged directly with other members: asking for help, commenting, or responding to a request for help. Indeed, my study had determined that responding to another member's request for help or advice was the second most common online activity. (The most common activity was general commenting activity). These trends in types of participatory behavior revealed a community where the dominant forms of participation were social and conversational: oriented toward the community and not one's own personal activities. Interviews also revealed that some members were actively assuming informal moderator roles online in the interests of safeguarding or promoting the community and ensuring it remained a welcoming and positive space.

[4.5] In short, there was a strong culture and ethos of community-oriented activities already at work in the Perth LUG; and although I was (and am) a member and thus already part of that culture and participatory behavior, I was nevertheless surprised at the study findings. I had not realized how important the social aspects of both the online and off-line activities were to members. Moreover, I had assumed that online participatory behavior that highlighted a member's activities with Lego, such as posting pictures of their own projects, would form a much higher percentage of activity than it actually did (it was the third most common online activity, only 12 percent of all activity). It was on that assumption that I had designed my fannish gifts to the community: a series of MOCs to be photographed and shared online. At the outset of the project, I did not have a clear vision of what those MOCs would be, just that I would tap into the very activity that draws AFOLs together—a love of Lego—and use the versatility of the medium to bring pleasure to a group known for its appreciation of creativity and humor (Garlen 2013). It was a project that sought to use the creative or play-based practices of the community to convey research data in an accessible and pleasurable way, to speak to the group in our common language, and to make a gift of my labor, time, and creative energy (to say nothing of the expense of building custom models!). As Hellekson recently advised, "Fan scholarship that engages in the aesthetics or forms of fan production definitely ought to be promoted" (Brooker, Duffett, and Hellekson 2017, 70), and while not all fan practices create or produce things that are shareable, I was fortunate that AFOL cultures certainly do—the custom built MOC being a particularly admired and valued activity in the AFOL world (Garlen 2013).

[4.6] To capture the qualitative experience of interviewing seventeen members of the community, I designed and built a laptop out of Lego that featured the participants of my study breaking out of the confines of the Perth LUG Facebook page and coming to life (figure 2). In most cases, the minifigures (Lego figures) were modeled on the participants of the study and what I had learned of them personally and professionally through the face-to-face interviews (figures 2, 3, and 4). For some participants, I was able to create a minifigure with such a strong resemblance to the participant that they could have been identified by community members, and thus I needed to secure additional permission from the participant (which was usually granted). Three participants of my study elected to be interviewed online instead of face-to-face and were provided with written questions to answer at their leisure; however, this experience significantly diminished my opportunity to get to know them as fellow members and resulted in considerably less data. These participants did not come alive for me and are represented as gray and uniform in appearance, still stuck behind the laptop screen (figure 4).

Figure 2. Laptop MOC.

Figure 3. Laptop MOC keyboard detail.

Figure 4. Laptop MOC minifigure details.

[4.7] Technically, this was the most challenging MOC I had ever built. A process of trial and error, it took several months to complete and required me to engage in some of the most common online activities of the Perth LUG group: asking for and receiving help. On the Perth LUG Facebook page, members helped answer my questions about design features and sourcing the necessary materials. One member who was not a participant of the study even gifted a needed minifigure to me (note 4). As a mechanism for conveying the quantitative data this study produced, however, the Laptop MOC was something of a failure: save for demonstrating the number and (in some cases) gender of my participants, the Laptop MOC ultimately revealed little hard data. What it did do was capture, through metaphor, the research process and experience—at least from my perspective. But playing with metaphor ultimately provided me with the tools to build another MOC that could capture quantitative data and do so in a way that required few special skills, simple and cheap parts, and took less than two hours to construct: the Data Towers MOC (figure 5).

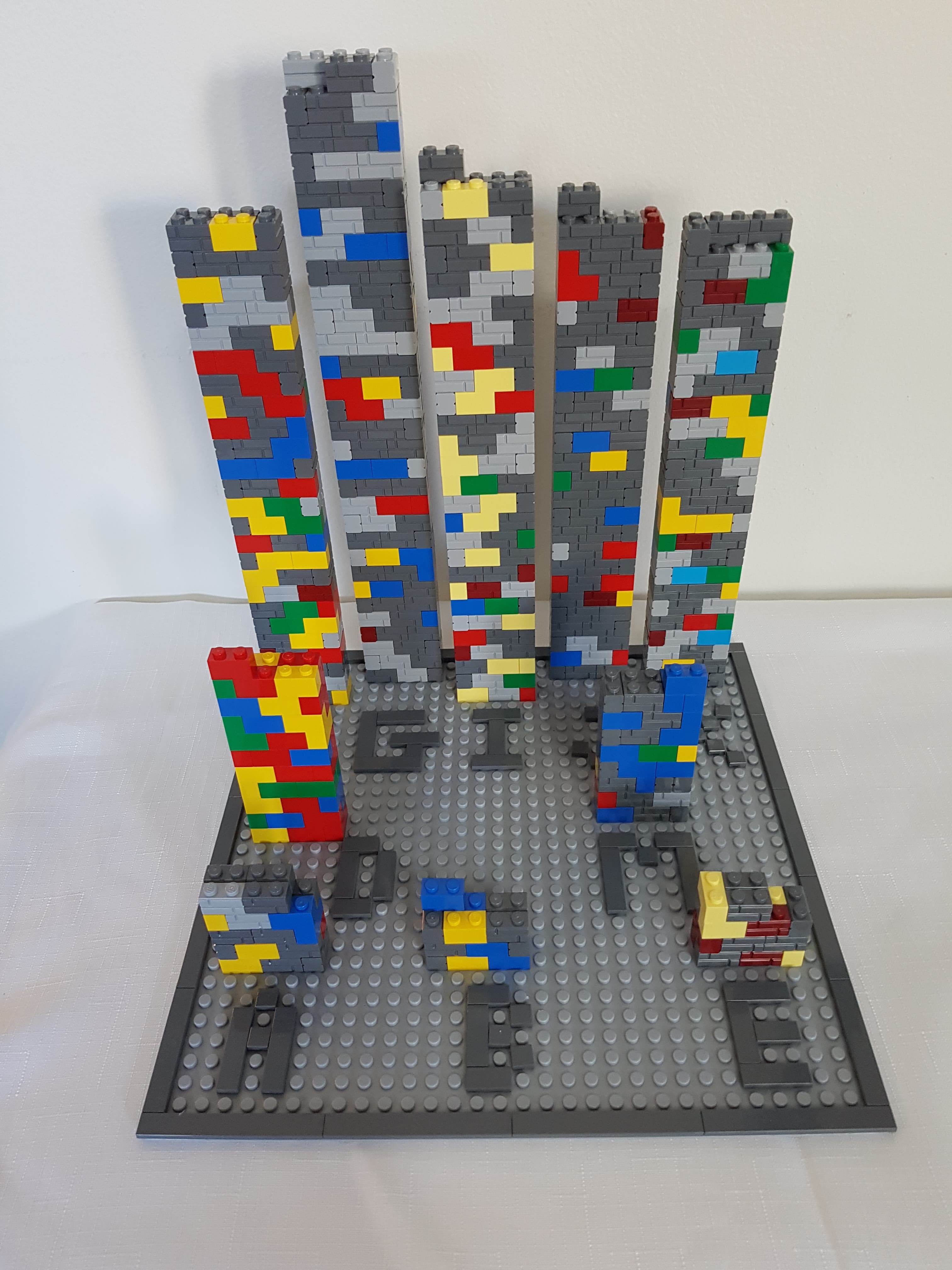

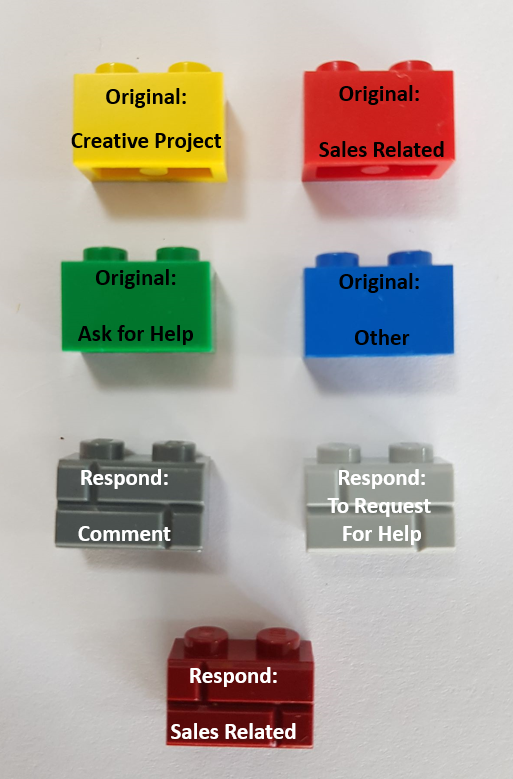

[4.8] The Data Towers MOC was a much more straightforward representation of the quantitative data the study produced about online activities. There is one tower per participant whose code name accompanies their tower, and each tower represents the entirety of their online activities on the Perth LUG Facebook page for a year (note 5). All Lego bricks used to make the towers were the same size (one brick high and two studs across—in Lego terms, a 1x2 brick) but different colors to indicate the different activities (figure 6). Each brick represented one instance of an online activity, such as posting a comment, picture, information, or link (note 6). The towers thus captured both frequency of online contributions and type of contribution. Brightly colored bricks were used to represent original posts—posts that were not a response to another member's activity (note 7). Modified bricks (bricks that look like masonry bricks) were used to capture responsive posts—posts that were made in response to another member's activity (note 8).

Figure 5. Data Towers.

Figure 6. Data Towers legend.

[4.9] From the Data Towers MOC (figure 5) and the Data Towers Legend MOC (figure 6), several findings of the study can be easily identified. Based on the different heights of the towers, we can see there were three different frequencies of participation. High Frequency Participants, who posted an average of ten to twelve times per month, are visible in the back row, and are fairly numerous. Medium Frequency Participants, who posted on average four times a month, are visible in the middle row. Low Frequency Participants, who posted on average one to two times a month, are visible in the first row. We can also see that participants' particular patterns of behavior could vary quite significantly, an element that was lost when the cohort's activity was represented statistically as a whole.

[4.10] Using different colors and textures of Lego bricks to represent different activities also helped to communicate how certain behaviors dominated. While "Respond: Comment" (a post that offers a general responsive comment) was the most common activity, as can be seen from the volume of dark gray modified bricks, the Data Towers MOC also makes visible how frequently members would respond to each other's requests for help (light gray modified brick). The sheer mass of light gray and dark gray modified bricks in the Data Towers MOC shows quite dramatically how dominant these behaviors are; in fact, responsive behaviors (represented with modified bricks) accounted for 65.3 percent of online activity, whereas original posts (represented with brightly colored bricks) accounted for 34.7 percent of all activity. Responding to each other's posts was, the study revealed, not only a dominant activity but crucial to the social fabric of the group. To capture how important these types of responsive behaviors were to the community, I choose to use the modified brick that has a masonry brick appearance to convey the sense that these activities are the building blocks of the community.

[4.11] Original posts—posts that were initiated by members to share their creative practices (yellow bricks), to discuss sourcing Lego (red bricks), to ask for help (green bricks), or other activities (blue bricks)—were less frequent than responsive posts but nevertheless played a crucial function in contributing content to the page and launching conversations. To capture the life and color that these original posts bring to a page, I used brightly colored Lego bricks that stood in marked contrast to the muted tones of the modified bricks used to represent responsive behaviors (figure 6). These bright colors helped visualize certain trends that I had not previously recognized, and made evident how responsive posts might create volume and traffic on the page but that original posts provided the bright moments of creative life. Captured in this way, I had a newfound appreciation for Participant D's online activities: this participant rarely commented on other members' posts, although they actively responded to posts in threads they had initiated. Statistically, this lent the appearance of a participant not actively engaging with the community, but through visualizing the data in the Data Towers, I was able to appreciate the vibrant contributions this participant was bringing to the Facebook page through sharing their creative work and their information on sourcing affordable Lego. (This was a member who also regularly gave away Lego or mailed Lego to buyers without having first received payment.) By volume of activity, Participant D may not have been a high-frequency contributor, but no other participant offered more by way of contributing original posts to the page.

[4.12] The final MOC I offered the Perth LUG community was not actually one I had built myself; rather, I'd had the academic audiences I had presented my findings to perform that creative labor. On two separate occasions in 2019, I had an opportunity to present papers about this project: at the Popular Cultural Association of Australia and New Zealand conference at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) in Melbourne and a Media and Communication Research Colloquium at the University of Western Australia (UWA) in Perth. At the beginning of each talk I distributed plastic containers full of disassembled minifigure parts to the audience. Each container had various heads, torsos, legs, and accessories. Audiences were invited to play with the Lego during my talk—in essence, to build their own minifigure out of the admittedly eclectic range of parts I had curated. At the end of my talk, audience members were invited to contribute their creations to my research project (figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. RMIT, July 2019.

Figure 8. UWA, October 2019.

[4.13] My purpose was to engage these academic audiences in the activities of play and fandom so that they could begin to appreciate the joy of Lego and feel some affinity for AFOLs who often have to combat the stigma of a hobby based on what is perceived to be a child's toy. The enthusiasm and creativity with which the audiences embraced this task took me by surprise; not only were the results of their labor delightfully bizarre and fun, but the audience members also reported that they enjoyed the task. At RMIT, some audience members had even taken to Twitter during my talk to share their creations, a move that anticipated my desire to have them use the Lego to interact with each other.

[4.14] This practice of getting academic audiences involved by building their own minifigures and sharing their creative labor with the fan community through photos enabled me to break down barriers between the two groups. In bringing the academics into the fan practices, I could help those audiences understand and empathize with the fan community; by sharing the academics' minifigures with the fan community, I could challenge perceptions of academics as distant and remote observers while also reversing the gaze and enabling fans to cast their gaze upon the creative works of the academic community. As with the Laptop MOC, these Minifigure Collection MOCs could not convey much research data; instead, the focus fell more on the experiences and activities of research as well as the practices of producing creative works to feed back into the community.

5. Evaluating the strengths and uptake of the gifts

[5.1] As a mechanism for sharing the findings of the research, each of these four projects had considerably different strengths. The report was able to communicate a vast amount of quantitative and qualitative data, far more than the MOCs could have achieved. Of the MOCs, the Data Towers MOC was able to capture some of the key quantitative findings about online participatory behaviors, including frequency and type of Facebook activity. By carefully curating the materials for these towers, I was able to use metaphor to extend and extrapolate on these findings. The other two MOCs proved more useful for conveying research process and practice than research data, an aspect of sharing research with fan communities that can be useful for demystifying academic activities and being more transparent about the practices and effects of our research.

[5.2] If we measure the efficacy and success of sharing our research by the quantity and quality of research data communicated, then the creative-practice techniques are at a distinct disadvantage. But if the project is to use the research to give back and to make of our research and labor a gift for the benefit of the community, then how the community responds to and engages with these gifts is of particular importance. Such responses can tell us whether our gifts were appropriate, welcome, or even useful: Did the community see and interact with the gift? Did they express interest in it? Did it align with community norms or participate in and affirm the values, cultures, and practices of the community? In Hellekson's (2009) gift economy trifecta—to give, to receive, and to reciprocate—these questions focus on the latter conditions: Are these gifts received into the community? Do community responses to these gifts form a kind of reciprocation; that is, do they make visible their pleasure or gratitude in ways that might bring reciprocal pleasure?

[5.3] By observing the fan community's engagement with both academic and fannish gifts, I sought to determine whether either could fulfill my desire to give back to and participate in the gift economy of the community. My expectation was that the community would be more interested in the creative practices, but the level of engagement with the report and, indeed, other academic documents was surprising. The report was initially available as a pdf on Academia.edu that tracked views and downloads but required participants to become members of the site. It was quickly moved to Researchgate.net, which tracked reads and full text reads but did not require login or membership in order to view. A notice about the availability of the report was posted to the Facebook page and links to the pdfs were sent to each member who requested a copy. A total of twenty-two Perth LUG members requested links and links were also sent to three group administrators. Academia.edu reported the report was viewed forty-nine times and downloaded eight times; Researchgate.net reported that the report had been read fifty-one times with twenty-seven full text reads. Although the general public would also have had access to the report on both sites because it was public, most of this activity occurred within days of sending the links to members and is assumed to be predominantly from the Perth LUG group. No doubt some members accessed the report through both sites and possibly returned to it more than once (hence increasing the number of visitors), so the most accurate tally of interest should be derived from the number of links to the report I sent out by request—twenty-two. Of those twenty-two members, seven were participants in the study.

[5.4] At the time of sharing the research results, the Perth LUG membership had over 2,600 members on its Facebook page with participation rates of approximately 10 percent (according to one of the administrators). Nevertheless, I consider the level of interest in the report quite high; in fact, more members sought to access this report than interacted with the posts sharing the Data Towers (figure 5) and Minifigure Collections (figures 7 and 8). The report also prompted some members to send feedback privately through Facebook Messenger. Some of this feedback was to highlight a date typo, but two sought to comment on the findings and another requested permission to share the report further. The membership also demonstrated interest in other academic forms of this research. I had notified the community via the Facebook page when I was presenting my research at RMIT and at UWA and, in response, one member of Perth LUG requested (and was granted) a copy of the conference paper delivered at RMIT and another member attended the talk delivered at UWA and actively participated in the Q&A that followed. This level of interest and engagement with both the report and the conference papers suggests that academic and text-based forms for sharing research can be taken up enthusiastically by both participants in the study and the community at large. But it is also a keen reminder that we should make all forms of our research available to our fan communities and not presume that academic discourses and forms are unwelcome or inaccessible. Hence, both this methodology paper and the paper detailing the study results will be shared with the community when they are published.

[5.5] Of the three MOCs photographed and shared to the Facebook page (there was a separate post for each MOC), the Laptop MOC was a clear fan favorite. The Data Towers and the Minifigure Collection MOCs prompted thirteen and twelve Facebook emoticon usages, respectively: two loves, two wows, nine likes, and two comments for the Data Towers; and two loves and ten likes for the Minifigure Collections. The Laptop, on the other hand, prompted ten loves, twenty-two likes, and eleven comments. While some of the Laptop comments were directed at requesting a copy of the report, many of them were also clearly enjoying the opportunity to see if they could identify themselves or other members in the minifigures bursting out of the laptop. Other participants contacted me privately through Facebook Messenger to see if they could correctly identify themselves and seemed pleased with how they had been interpreted in the MOC. As with the report, there was a similar ratio of study participants to non-study participants actively engaging with this MOC (where 32 percent of activity with the report came from study participants, 28 percent of activity with the Laptop MOC came from study participants), but it was predominantly the study participants who were keenest to identify the minifigures. AFOLs tend to delight in realism and accuracy, particularly with MOCs, so this impulse to identify each other was not driven by vanity alone; moreover, the fact that members thought they could potentially identify other members affirms the study's findings that some members of the group are remarkably social and close-knit for an online community. As I had anticipated there would be curiosity about the minifigures' identities and recognized that this raised a potential ethical issue of compromising the anonymity of study participants, all participants who could be clearly identified signed additional permission to be represented identifiably. The risks involved in being identified, however, were determined to be fairly minimal because little research data is actually conveyed by the MOC and no data (save gender) is connected to each minifigure representation.

[5.6] In short, both academic and fannish gifts were received into the fan community: study participants and the community at large engaged with these gifts in visible ways and made their pleasure and interest known to me in both public and private forums. While the most technically challenging MOC prompted the highest number of responses, the marked enthusiasm for the build likely stemmed from the custom features that invoked and represented the Perth LUG community: this was more than just a technical build, it was designed with a very particular audience in mind. Like the report and the Data Towers MOC, the Laptop MOC could capture certain elements of the community and reflect these back to itself. But unlike the report and Data Towers, the Laptop spoke to the community in its own language. This is more than a matter of medium—Lego—but of what is valued and embraced about the medium—its versatility, its capacity for realism, interpretation, and humor, and its role as a conduit for narrative and creative play. And yet because the Laptop MOC was technically challenging, it was also the gift that brought me, as the gift-giver, more firmly into the gift economy because I required the community's help to design, source, and build it: I received advice, encouragement, and even gifts of Lego in the process. Building this MOC meant involving the community and working with them and thus it was that particular project rather than the others which seemed to capture the spirit of giving, participating, and contributing.

[5.7] Nevertheless, the other projects served important functions in this project. I had not anticipated the community's interest in the research, the report, and the conference papers, and I had not anticipated how keenly academic audiences would embrace fannish practices in an academic setting. Sharing what the academic audiences had made back into the community provided a crucial opportunity to facilitate a better understanding of these two groups to one another in a safe, respectful, and playful format. To my mind, creating the conditions through which these groups might develop a better mutual understanding of each other represents one of the extraordinary opportunities of acafan research, but it comes with particular risks and liabilities. We must be mindful that we do not expose either fans or academics to unwelcome exposure, embarrassment, or discomfort and that we do not appropriate cultures and practices or encourage others to do so. This study had distinct advantages in mitigating those risks because Lego provides a natural medium for play and creative practice and AFOL cultures encourage both experimentation and sharing their interests. Lego has also had a broader visibility in the public sphere since 2014, when The Lego Movie became a critical and commercial success around the world; moreover, AFOL activities entered mainstream popular culture in Australia in 2019 with the notable popularity of Nine Network's Lego Masters Australia TV series. This study of AFOLs and their activities, then, as well as the practices of sharing this research with both academic and AFOL audiences, was well positioned to take advantage of a general interest in and familiarity with the notion that adults can (and should) play with Lego.

6. Conclusion

[6.1] Sharing our research with the fan communities we study has long been encouraged as a means of creating transparency about the academic process and offering communities an opportunity to give feedback. But, as Dym and Fiesler (2020) have suggested, it can also be a way to give back to the community: we can transform our research into something interesting and even valuable to the community. It is possible to make of our labor and research a gift and, as this study has demonstrated, such gifts can emphasize the "aca" of our acafandom, but they need not do that exclusively. Creative fannish practice can offer rich possibilities for engaging with, giving back to, and participating in the community. It can be a source of pleasure and delight for academics, for fans, and for the acafan, and ought to be carefully considered as a mechanism for sharing research, particularly in conjunction with more academic and text-based forms like the report. Together, the academic gift and the fannish gift can share more than just research data; they can capture and demystify the research process, they facilitate a better understanding of both academic and fan communities, and they can get both communities involved and invested in the research. Creating a fannish gift, however, requires careful consideration and can involve significant time and energy; but for the acafan already committed to these cultures and practices, such a project can be personally, professionally, and creatively rewarding. Sharing our creative projects with our colleagues and our fan networks may require some courage but, in the spirit of gift giving, we can hope that they are received with the same hospitality with which they are shared.

7. Acknowledgments

[7.1] I'd like to acknowledge and thank the administrators of the Perth LUG for supporting this project and all the members who so generously donated their time to participate.