1. Introduction

[1.1] "Harley fever has exploded! Now anybody can be Harley Quinn!" reported a young Lois Lane in a 2016 episode of the animated web series DC Super Hero Girls. (Warner Bros. Animation/YouTube, 2015–18). Released the same year as Harley Quinn's live-action cinema debut in Suicide Squad (2016), the web series acknowledged how the chalk-faced antihero had become a fan favorite. Harley Quinn's creation is credited to writer Paul Dini and artist Bruce Timm, who introduced the character as the love interest/sidekick of Batman villain the Joker in a 1992 episode of Batman: The Animated Series (Fox Kids, 1992–95), "Joker's Favor." This first appearance quickly positioned the character in a carnivalesque tradition that celebrates the upending of dominant structures through chaos and comedy. The episode depicts Harley Quinn, wearing a full-body jester outfit and white face paint, crashing a formal testimonial dinner for Gotham City police commissioner Jim Gordon with an oversized cake and Joker-themed explosives. This anarchic humor and irreverence would become a trademark of the character as Harley Quinn was extended into other media platforms. Dini and Timm's 1993 one-shot comic book, The Batman Adventures: Mad Love, revealed the character's origin as an Arkham Asylum psychiatrist, Dr. Harleen Quinzel, who fell in love with her patient, the Joker, and ultimately became his accomplice. The character was not added to "official" Batman comic book continuity until 1999, in the Paul Dini–written story Batman: Harley Quinn. This comic book version maintained Harley Quinn's established appearance, personality, and origin.

[1.2] As comic book intellectual property moved to the center of a number of creative industries in the early 2000s, Harley Quinn became a transmedia icon appearing in comics, television series, theme park rides, video games, and movies. In 2009, one of the first significant changes to the character occurred when Harley Quinn was included in the successful video game Batman: Arkham Asylum (written by Dini). In the game, Harley Quinn's traditional costume was replaced with a nurse's outfit, which has proven popular with cosplayers. As part of DC Comics' 2011 companywide reboot, titled "The New 52," Harley Quinn received an even more revealing outfit and a revised backstory in which her skin was bleached white by the Joker when he threw her into a vat of acid.

[1.3] Although Harley Quinn was a regular feature of animated and television adaptations, 2016's Suicide Squad marked the character's first appearance in a live-action feature film. This version of Harley Quinn, played by actress Margot Robbie, retained the character's updated origin and "kinderwhore" look (Geczy and Karaminas 2019, 176), replete with a ripped "Daddy's Little Monster" T-shirt, fishnet stockings, and "Puddin" choker. A version of this costume was also introduced to the comic books and was widely performed by cosplayers. Recognizing the character's growing popularity, in most transmedia iterations Harley Quinn is increasingly depicted as having cut her ties to the Joker. Examples of this more stand-alone character include the adult animated series Harley Quinn (DC Universe/HBO Max, 2019–present) and the feature film Birds of Prey (and the Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn) (2020).

[1.4] Throughout the character's transmedia ascent, Harley Quinn has maintained a dedicated fan base (Roddy 2011). Drawing on fan interviews carried out at comic book conventions and stores, as well as interviews with key writers and artists, I argue that the character of Harley Quinn has been used by fans and industry stakeholders to transform long-standing definitions of comic book fandom. Specifically, the analysis charts how the character has been used to forge new pathways into comic book fandom, displace the privileged position of the comic book, and address the superhero genre's limited representation of gender and sexuality. Although many comic book characters have transformative potential, Harley Quinn's invocation of carnivalesque traditions makes the antihero an ideal instrument to challenge the boundaries of comic book fandom.

2. Comic book fandom

[2.1] In the Anglosphere, comic book fandom has frequently been treated as a niche, often impenetrable community. One of the most visible examples of this perceived gatekeeping is the comic book community's long-standing reputation as a "no girls allowed" club populated by maladjusted fanboys who only read superhero comic books. For example, one male participant in this study remarked, "When it comes to comics, I think there's still very much [an idea] that it's a boys' club, but as [comic book content] gets into more popular media like movies, people aren't going to bat an eye if a girl says, 'I like the Marvel movies,' but if they say they read Marvel comics, I think that it's going to be different" (R16) (note 1).

[2.2] There is a dearth of reliable data on gender and comic book readership; industry figures are not widely available, and most academic research on the topic stems from the 1990s (Healey 2008). This 1990s scholarship highlights the traditional boys' club view of comic book fandom. For example, Jeffrey A. Brown (1997) cites surveys that indicate that 90 percent of comic book fans are male, a demographic consistency Brown also noted in a 2000 study. Similarly, Matthew J. Pustz observed that at the comic book store where he carried out his primary research, "most regulars are male…and relatively young" (1999, 5). Media representations of comic book culture such as the Comic Book Guy from animated series The Simpsons (Fox, 1989–present), Kevin Smith's reality television series Comic Book Men (AMC, 2012–18), and the geek superhero enthusiasts of TV sitcom The Big Bang Theory (CBS, 2007–19) have further cemented the boys' club stereotypes. These often unfavorable depictions have found some comic book readers rejecting the label of comic book fan. For example, Stephanie Orme speculates that female fans often downplay their fandom to avoid stigmatization, concluding, "this could explain why popular culture continues to promote narratives of the 'rare' female fan—because they are rendering themselves invisible" (2016, 413).

[2.3] Despite the persistence of certain representations, there is growing evidence that comic book fandom is widening in the Anglosphere. Responding to a 2011 survey that indicated 93 percent of DC Comics readers were men, Suzanne Scott argues that these studies fail to recognize the "anecdotal evidence [that] suggests that the female readership for comics has been growing over the past decade" (2013, ¶2.7). More recently, Orme has described the mounting evidence of the increasing number of women in comic book culture: "Survey data from comic book stores report that women may comprise somewhere between 40 and 50% of their consumers." She adds that women "also seem to be a rapidly increasing percentage of attendees at comic book conventions" (2016, 403–4). The gender breakdown of attendees at Oz Comic-Con, where some of this study's interviews took place, supports Orme's assessment; visitors to the 2018 convention were 58 percent female, 41 percent male, and 1 percent "self-identifying" (i.e., nonbinary) (Oz Comic-Con 2018).

[2.4] Responding to Suzanne Scott's call "for more scholarship on comic book audiences" (2013, ¶6.4), I here draw on thirty-two semistructured interviews with self-described Harley Quinn fans, as well as interviews with relevant comic book writers and artists, including the character's cocreator, Paul Dini (note 2). The selection criteria for participation were that respondents were adults who could consent to partake in interviews and who described Harley Quinn as one of their favorite characters. Twenty-three of the respondents identified as women and nine as men. Scott has described how "we are currently witnessing a transformative moment within [the] comic book industry, comic book fandom, and comic book scholarship, in which gender is one of the primary axes of change" (2013, ¶6.3). However, Scott later reminded scholars to adopt an intersectional perspective that considers "how additional axes of identity beyond gender (race, age, sexuality, ability, etc.) shape fan identities" (2019, 16). Although much of my analysis in this article focuses on gender, this study's respondents identified a number of other factors that have curtailed their entry into comic book culture, including expertise, age, income, sexuality, ethnicity, and access. However, these boundaries are increasingly being tested, and in some cases the mallet-wielding Harley Quinn has been enlisted to help break them.

[2.5] Of the 113 participants in my earlier study of comic book movie cinema audiences (Burke 2015), little more than half of the self-described comic book fans read comics of any kind (132). Similarly, Orme (2016) noted how many fans have "never picked up a comic book" (406); hence, she defines "comic book culture" as going beyond print comics to include "digital comics, comic book-based films and television shows, and the various conventions and social gatherings attended by comics fans" (407). Although the majority of this study's respondents identified themselves as comic book readers (88 percent), most described being introduced to comic books via audiovisual and/or fan versions of the characters. Accordingly, here, I do not limit comic book fandom to readers of monthly superhero comics distributed via comic book stores. Rather, I consider a comic book fandom that reflects post-2000 shifts in the industry and audience by including the many activities and texts that orbit comic books such as comic book conventions, comic book adaptations, and superhero cosplay. Harley Quinn's transmedia popularity is not just symptomatic of this widening comic book fan community; the character is also a colorful conduit by which such changes have been achieved.

[2.6] This study's fan interviews were carried out at the popular culture conventions Supanova, Oz Comic-Con, and AMC Expo, which were held in Melbourne, Australia, in 2016 (video 1), as well as at the Eisner Award–winning Melbourne comic book store All Star Comics during the Harley Quinn takeover of Batman Day in 2017. Such interviews are in keeping with similar studies on fan culture. For their separate articles on stigmatization and female fandom, Neta Yodovich and Stephanie Orme both used semistructured interviews with fifteen adult women fans. In explaining her approach, Yodovich described how semistructured interviews enabled her to "obtain an extensive and detailed view of the lives of women fans" (2016, 295). Orme, citing Thomas R. Lindlof and Bryan C. Taylor, argued that "narrative interviews aim to capture entire stories that present a larger picture of the phenomenon being studied" (2016, 407). The often lengthy responses in this study were postcoded for repeated patterns; when triangulated with appropriate conceptual frameworks and a close analysis of the primary texts, these interviews offered a more rounded understanding of a dynamic comic book culture and the cackling clown who has been used to help cajole it into existence.

Video 1. "Unmasking Harley Quinn," a video montage of some of this study's participants offering their thoughts on Harley Quinn.

3. Multiplicity and the carnivalesque

[3.1] Neal Curtis and Valentina Cardo note how the dual identities of all superheroes "automatically lend themselves to intersectional theories of identity," but they argue that "Harley's identity is a complex constellation of related yet contradictory positions" (2017, 385). When asked how they would describe Harley Quinn, this study's fans also highlighted the character's multiplicity: "She toes the line of kind of psychotic and creative but cheeky" (R25); "She almost has multiple personalities that she sort of just switches between, and that's part of what her character is" (R17); and "It's like tossing a coin: you can be good, you can be bad, you can be flirtatious, or you can be serious" (R2). Comic creators also identified this multiplicity with artist Nicola Scott, who illustrated Harley Quinn in Secret Six, remarking how "there's this mercurial nature that's so hard to pin down, but that is what keeps giving her life and keeps making her interesting for writers." Tom Taylor, who has written the character in the bestselling Injustice comics, observed that "there's this tragedy mixed with unbelievable comedy" (Larson et al. 2016). For this study's respondents, Harley Quinn's multiplicity was a key aspect of the character's appeal and has been embraced by the larger fan community, who extend the range of interpretations through a host of activities such as fan fiction, fan art, and, in particular, cosplay.

[3.2] Harley Quinn's multiplicity is appropriate for a character indebted to commedia dell'arte (note 3), a sixteenth-century form of theater that is often considered a continuation of earlier carnival traditions (Scuderi 2017). When Mikhail M. Bakhtin conceptualized the carnivalesque as a literary mode, he explained, "The scope and the importance of this culture were immense in the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. A boundless world of humorous forms and manifestations opposed the official and serious tone of medieval ecclesiastical and feudal culture" (1984, 4). In describing Bakhtin's affinity for transgressive rupturings, Robert Stam notes, "Bakhtin's oxymoronic carnival aesthetic, in which everything is pregnant with its opposite, implies an alternative logic of nonexclusive opposites and permanent contradiction that transgresses the monologic true-or-false thinking typical of Western rationalism" (1989, 22). This rebuttal of all-or-nothing binaries tallies with the ideas of multiplicity that the character of Harley Quinn so colorfully embodies. In fact, a number of scholars have attributed carnivalesque qualities to the mallet-wielding antihero. Pointing to BDSM to challenge critiques of Harley Quinn's relationship with the Joker as antifeminist, Kate Roddy acknowledges Harley Quinn's manifestation of the carnivalesque, explaining, "Like the characters of the commedia dell'arte from which Harley Quinn takes her persona (Harlequin), BDSMers belong to the world of Bakhtin's carnivalesque" (2011, ¶3.28) (note 4). Similarly, Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas describe Harley Quinn's costumes in the film Suicide Squad as "a highly carnivalesque form of punk and bondage styling" (2019, 175–76).

[3.3] Although Bakhtin believed that folk-carnival reveling has only continued in "impoverished" forms since the high point of the Renaissance (2011, 130), depictions of Harley Quinn often evoke carnival traditions. Many Harley Quinn stories find the character fulfilling the four categories of the carnivalesque Bakhtin identifies in Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. The first category is "free and familiar contact among people…who in life are separated by impenetrable hierarchical barriers" (2011, 123). Likewise, on page and screen, Harley Quinn is often depicted breaking down taken-for-granted boundaries by forging unlikely alliances. In the "Harlequinade" (1994) episode of Batman: The Animated Series, the capricious clown teams up with Batman to stop a Joker scheme, a premise reused with diminishing returns in the DC animated movie Batman and Harley Quinn (2017). Similarly, promotional materials for the feature film Birds of Prey highlighted Harley Quinn's unexpected team-up with the Birds of Prey superhero team.

[3.4] In the second category of the carnivalesque, which Bakhtin terms "eccentricity," "the behavior, gesture, and discourse of a person are freed from the authority of all hierarchical positions" (2011, 123). Peter Coogan notes of the supervillain's "criminal artistry" that "crime is a theatrical art, with actors, audience, and performance and it can be appreciated aesthetically" (2006, 80). Like her ex, the Joker, Harley Quinn's actions are often criminal and artistic, but where the Joker's eccentric behavior is not condoned, Harley Quinn's criminal artistry is not only accepted but often celebrated. For instance, the Christmas-themed comic book story "The Not So Silent Night of the Harley Quinn" (writer: Paul Dini; artist: Neal Adams, 2016) opens with Harley Quinn breaking into a Gotham City police station to deliver gifts to the police. When Batman intervenes, Harley Quinn explains, "C'mon Bats! What'd you expect me to do, dance in the front door? Not with my rep," with Batman accepting her explanation despite the hero's usual zero tolerance for crime.

[3.5] Bakhtin's next category is "carnivalistic mésalliances" (2011, 123). Many Harley Quinn stories embrace the mischievous incongruity of unlikely team-ups, or, in more risqué versions, unlikely romantic hookups. For instance, Harley Quinn is regularly depicted riding shotgun in the Batmobile, with the character's irreverent style contrasting with Batman's practiced stoicism. Harley Quinn is often shown to be successful at cracking the Dark Knight's tough veneer, gaining the smiles, kisses, and Christmas carol sing-alongs that have eluded the Joker and even Batman's dedicated sidekick, Robin. In Bakhtin's terms, Batman is the "official feast" (1984, 9), while Harley Quinn is the carnivalesque break.

[3.6] The final of Bakhtin's four carnivalesque categories is "profanation," a range of blasphemies and sacrilegious events occurring without punishment (2011, 123). Across the character's many transmedia appearances, Harley Quinn's humor is undeniably profane. For example, in the introduction to the Harley Quinn animated series, the protagonist pronounces, "When Gothamites hear the name 'Harley Quinn,' I want 'em to piss themselves!" In the next scene, she jokes that Batman "fucks bats" when apprehended by the straight-faced Caped Crusader.

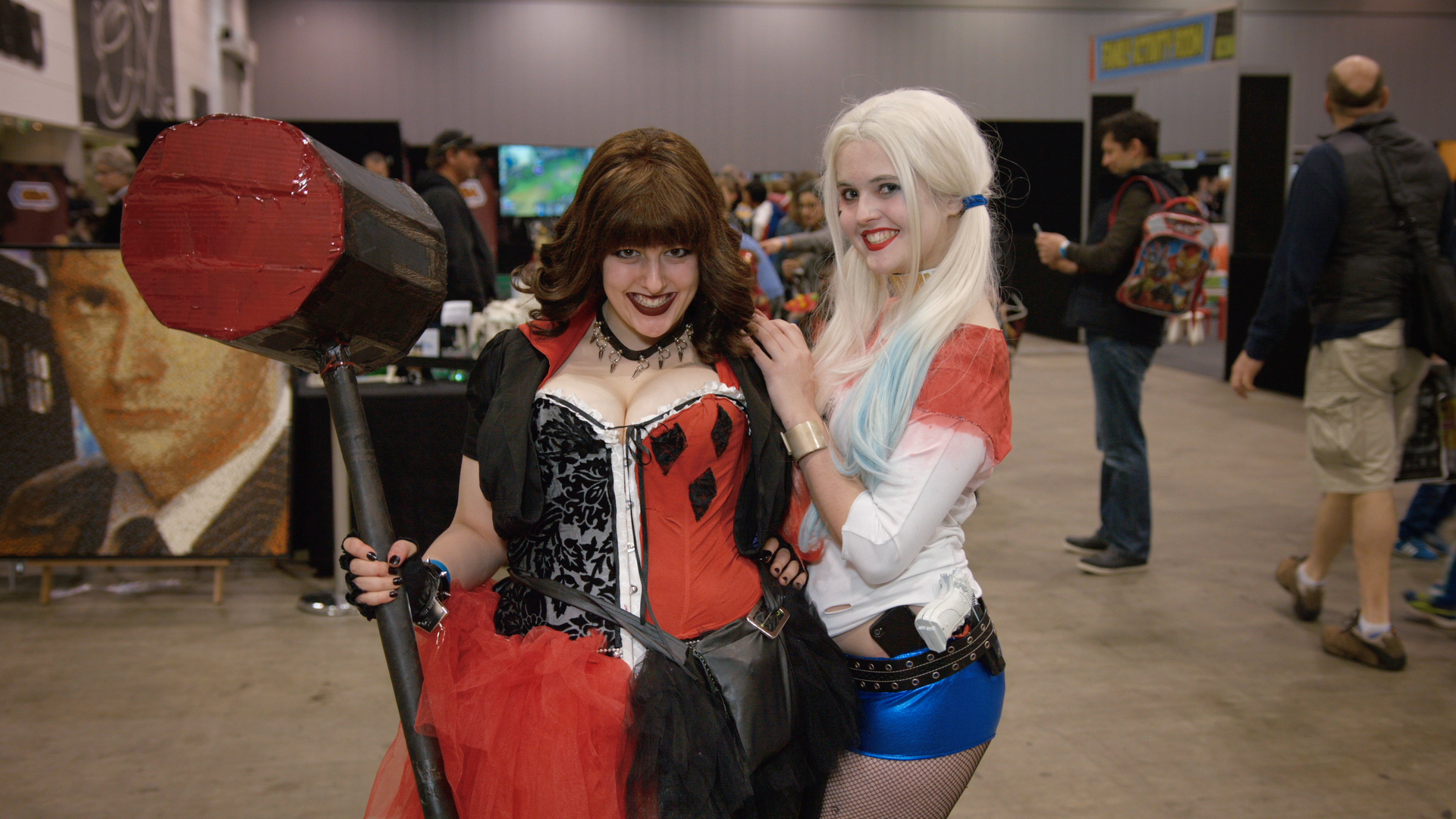

[3.7] I found that Harley Quinn fans embrace the character's carnivalesque qualities and continue them into their own interpretations (figure 1). For example, the character's cocreator, Paul Dini, noted of the freedom that Harley Quinn provides cosplayers, "You can become Harley and have fun and wise-ass somebody in the same way that you couldn't if you were not in costume." Indeed, cosplayers often celebrate how Harley Quinn licenses the eccentric behavior, profane humor, and free and familiar contact that Bakhtin identified as carnivalesque categories. As one cosplayer explained, "You get to put those theatrics into it [as Harley Quinn], and you get to have fun with the character and interact more with people. You can't run around and play jokes on people and kids as a superhero, but as a villain you can do that, and you can get away with it, and it's fun, and people love it" (R31).

Figure 1. Echoing Bakhtin's assertions regarding carnivalesque categories, a cosplayer shows how Harley Quinn permits more fun and interaction than a traditional superhero.

[3.8] Beyond celebration, for Bakhtin, the carnival had an emancipatory, even revolutionary potential, with the literary critic describing how the "carnival celebrated temporary liberation from the prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions" (1984, 10). Robert Stam identified the carnival as "the oppositional culture of the oppressed" (1989, 95). Indeed, more optimistic accounts describe how carnivalesque pleasures today might still provide strategies or models for structural transformation. For example, Kane Anderson has argued that the increasingly mainstream San Diego Comic-Con allows attending cosplayers to "temporarily redefine their places in the hierarchies of the outside world through enjoying the freestyle masquerade of Comic-Con's carnival-like atmosphere" (2015, 115). However, citing John Fiske's analysis of professional wrestling, Stam pessimistically noted that "American mass media are fond of weak or truncated forms of carnival that capitalize on the frustrated desire for a truly egalitarian society by serving up distorted versions of carnival's utopian promise" (1989, 226). Nevertheless, as Anderson suggests, even the heavily commoditized culture of comic book fandom can sometimes reverberate with a carnival spirit.

[3.9] A number of scholars have argued that comic books and comic book fan activity have transformative potential, even if it is not always fully realized. Suzanne Scott identifies the "transformative capacity" in superhero crossplay fan art like the Hawkeye Initiative for "superhero representations specifically and comic-book culture more broadly" (2015, 151). Nicolle Lamerichs describes the "transformative potential" of cosplay, which allows fans to "express who we are through fiction" (2011), while Carlen Lavigne acknowledges the "transformative potentials" of superhero comics and games, but adds that this has been limited "as they have been targeted primarily and even exclusively toward straight, white, male audiences" (2015, 133). Bakhtin's conceptualizations of the carnivalesque not only help us to better understand Harley Quinn's appeal but also help us see how audiences and the industry have used the character to widen the boundaries of comic book fandom. As the following sections detail, these transformations include circumventing comic book store gatekeeping, challenging the print comic book's privileged status, and redressing the limited representation of the superhero genre.

4. New pathways into comic book fandom

[4.1] In the late 1970s, comic book publishers began moving away from costly newsstand circulation to distributing their print comic books through comic book stores. This direct distribution strategy led to comic book stores' becoming for many the central hub of comic book fandom. However, these dedicated forums also contributed to comic book fandom's separation from wider society (Pustz 1999). Consequently, many enthusiasts, including a number of this study's respondents, found comic book stores (and by association comic book fandom) an inhospitable, even gatekept environment. For instance, one female Harley Quinn fan remarked on her first visit to a comic book store a couple of years earlier:

[4.2] I went to [a Melbourne comic book store], and it was such a shitty experience, because it was like, "I want to read comics, but I don't know where to start" […] And the staff there were awful. They were just like, "well, come back when you know what you want." How am I going to know that? So that was kind of shitty. But [All Star Comics] is amazing and everyone's so helpful. (R1)

[4.3] This anecdote recalls media representations of comic book stores, such as the Android's Dungeon in the animated series The Simpsons, as unwelcoming boys' clubs presided over by smug staff who are quick to criticize customers who do not share their encyclopedic knowledge of comics. This section charts how Harley Quinn's carnivalesque transgressions on page and screen have directly translated into fans, particularly women and girls, having more fulfilling experiences of the character and, more broadly, of contemporary comic book culture. In particular, I examine how fans used Harley Quinn cosplay to find pathways into the comic book fan community that bypassed the local comic book store. I also consider how industry stakeholders responded to this army of costume-clad enthusiasts.

[4.4] Bakhtin describes how "the basic carnival nucleus…belongs to the borderline between art and life. In reality, it is life itself, but shaped according to a certain pattern of play" (1984, 7). This definition could also be applied to the performance art of cosplay, in which enthusiasts dress as characters from popular culture at public gatherings like comic book conventions. Indeed, many scholars have identified the same carnivalesque traditions in cosplay that fuel Harley Quinn's appeal. These qualities include the "fluid boundary between self and world" (Mountfort, Geczy, and Peirson-Smith 2019, 86), "permission to be someone or something other than themselves" (Winge 2006, 75), and a "participatory culture" in which the "celebratory aspects of costuming are foregrounded" (Lamerichs 2014, 118). Given the many parallels, it is unsurprising that Harley Quinn has become a "frequent choice of cosplayers of all ages" (Taylor 2015, 82). As one of this study's respondents noted of Harley Quinn cosplay, "You go to any sort of convention, and whether it's true or not, but there's a stereotype now that you're going to see a hundred Deadpools and a hundred Harley Quinns. So I think that's become part of her identity, that cosplay aspect" (R16). Thus, while some trepidation persisted around comic book stores, this study's participants overwhelming described cosplay as a welcoming fan practice, with a typical response being, "People are amazingly friendly and they don't judge you" (R29). Accordingly, cosplay has often provided an opening in comic book fandom for new or marginalized fans, with artist Nicola Scott remarking when interviewed for this research: "I love cosplay. I think it's a great entry point for young fans, and it's a great entry point for women to fandom."

[4.5] Many respondents linked the interest in Harley Quinn cosplay to Margot Robbie's performance as the character in the 2016 film Suicide Squad. However, Harley Quinn was a cosplay favorite long before that film's release. Christopher McGunnigle (2018) observed cosplayers at the New York Comic-Con in 2011 and 2015 in order to track the "frequency of specific superhero characters in female cosplay." He noted that while some characters waxed and waned in popularity as a result of the visibility of their adaptations, Harley Quinn was the top choice in both years. This preference suggests that even though Harley Quinn's profile may benefit from adaptations, the character's purchase on contemporary comic book fandom, and in particular cosplay, is more stable than that of characters such as Black Widow, Batgirl, and Supergirl. This study's respondents provided a number of interrelated reasons for Harley Quinn's amenability to cosplay, notably achievability, variety, and fun.

[4.6] Rahman, Wing-Sun, and Cheung noted how many cosplayers "spend substantial amounts of time and money in meticulous attention to every detail," and "newcomers may find it difficult to engage in this activity if they do not have enough confidence, passion, enthusiasm, guidance, and support" (2012, 325). Many respondents described how Harley Quinn's costume is a more achievable cosplay than other superheroes. For example, one female fan considered Wonder Woman's outfits to be "too skimpy" (R8), and another observed how "it is a lot easier to get [Harley Quinn's costume] together, while Wonder Woman has so many little things it's very hard" (R4). A father attending Harley Quinn Day with his teenage daughter in Harley Quinn cosplay summarized the views of many:

[4.7] I guess the costume for Harley Quinn is probably more geared to anybody. For Harley Quinn, depending on which one you go as, you can wear leggings, you can wear shorts, you can wear a skirt or whatever whereas for Supergirl and Wonder Woman, it's pretty much a body suit and a skirt. Unless you're just super confident in yourself, most people aren't going to necessarily go for that. (R2)

[4.8] Lamerichs (2011) has noted how such "practical considerations" influence cosplayers (figure 2). For example, one of this study's respondents identified Harley Quinn's irreverence as inspiring a pragmatic reworking of the costume: "To be honest, it was the easiest costume. And you can like mix and match it up. I brought a hockey stick instead of a bat, because it's all I had. Uni[versity] life, you know?" (R20). As will be discussed in the next section, recognizing the popularity of Harley Quinn cosplay, DC Comics and WarnerMedia have further emphasized the character's achievable costume in many of her transmedia appearances.

Figure 2. A Harley Quinn cosplayer at Oz Comic-Con highlights the achievability of the character's costume by substituting Harley Quinn's trademark baseball bat for a hockey stick.

[4.9] The variety of Harley Quinn costumes also appealed to this study's respondents (figure 3). Illustrating the character's carnivalesque multiplicity, fans described how Harley Quinn invites any number of interpretations without cosplayer's feeling like they have performed the character "wrong." Typical responses included "There's a variety of ways to cosplay her, and I think that's why she is popular at cosplay" (R10); "[Harley] gives cosplayers quite a broad range to be able to work with […] there are just so many different variations" (R17); and "What I especially like about Harley is that she has got so many looks and that you don't have to follow one specific look and the fact that I can put my own version on the look and people can still get who I am as well" (R15).

Figure 3. Harley Quinn cosplayers at Oz Comic-Con illustrating the variety of interpretations the character invites.

[4.10] In their psychological survey of cosplay, Rosenberg and Letamendi (2013) found that "fun" was the most endorsed reason why their respondents cosplayed. Indeed, cosplayers often embrace how Harley Quinn facilitates the eccentric behavior that Bakhtin identified as carnivalesque. As one cosplayer explained, "She's quite comedic and fun, and every young girl wants the excuse to be able to just be totally crazy" (R14). Similarly, other respondents remarked, "You get to be someone different because Harley is so crazy and out-there and fun" (R15); "As soon as my makeup and my wig is on I'm no longer me, I'm Harley, I'm more confident, I'm more crazy" (R24); and "It's really fun to just be cheeky" (R25). As these responses demonstrate, this study's participants embraced the achievability, variety, and fun of Harley Quinn cosplay and used their costumed performance to signal their fandom (figure 4).

Figure 4. A cosplayer attending Oz Comic-Con in a Harley Quinn mash-up that demonstrates the variety and fun the carnivalesque character licenses.

[4.11] McGunnigle acknowledged how cosplay provided access to comic book fandom for some female fans, but argued that cosplaying as Harley Quinn and similarly sexualized characters can cater to the "interests of the masculine audience" and that a "female fan risks not only reinforcing gendered power structures but also losing herself to the sway of social conformity" (2018, 171). However, few respondents articulated these concerns; rather, they seemed to benefit from the "communal bonding" (Rahman, Wing-Sun, and Cheung 2012, 332) and "collective identity formation" (Mountfort, Geczy, and Peirson-Smith 2019, 5) available in cosplay.

[4.12] In contrast to misogynistic expectations that might pit female fans against each other, Harley Quinn cosplayers interviewed for this study tended to celebrate the free interaction Bakhtin identifies in the carnival. For instance, when asked if the many Harley Quinn cosplayers at conventions and other fan events created competition, most dismissed any rivalry: "You appreciate everybody in their own way bringing their own thing to Harley Quinn (R24)"; "They love that character for a reason, same as me, so you can go up and talk to them and be like, 'Oh my god, this is awesome'" (R31); and "There's been so many different Harley Quinns, so it's just interesting seeing what they wanted to do with the character" (R21).

[4.13] Such camaraderie reflects Harley Quinn's homosocial relationships in the character's transmedia appearances. For example, when freed from her abusive relationship with the Joker, Harley Quinn forges a number of alliances with other women such as Power Girl, the Birds of Prey, the Gang of Harleys, and the Gotham City Sirens. In particular, Harley Quinn is often depicted in a mutually supportive relationship with fellow Batman villain Poison Ivy, which varies from the pair being friends to lovers, depending on the version. Of this partnership, Shannon Austin notes, "Harley's proximity and alliance with Ivy actually makes her more powerful, cementing the almost terrifying idea that while a woman with power is dangerous, women helping women achieve power is an even more serious threat" (2015, 286). Finding parallels with the liberation implicit within these textual portrayals, many of this study's respondents indicated that they embraced the solidarity of a like-minded community after being isolated for so long. Stam describes how Bakhtin was "more interested in the symbolic overturning of social hierarchies within a kind of orgiastic egalitarianism" (1989, 89–90). Indeed, through their carnivalesque camaraderie, the often marginalized Harley Quinn cosplayers challenge the top-down imposition of hierarchies and bring visibility to their fandom.

[4.14] Although Harley Quinn fandom, including cosplay, was fueled by grassroots interest, DC Comics and WarnerMedia's recognition of the character's growing popularity has prompted attempts to corral fan activity. As discussed, the carnivalesque category of unchecked sacrilege has become one of Harley's trademarks. In 2017, DC Comics used this character trait to inject their annual Batman Day with an attenuated dose of carnivalesque spirit. To mark Harley Quinn's twenty-fifth anniversary the character hijacked Batman Day—with comic book stores hosting giveaways, creator signings, and cosplay competitions. As Fiske reminds us, the nineteenth-century fair was gradually banned in favor of an official holiday, with the expectation being that an official holiday "would be more amenable to discipline than a popular holiday that had a motive force from below" (2011, 62). Echoing this paradigm, events such as Harley Quinn Day can be seen as taking existing fan practices, including cosplay, and containing them within publisher-designated official holidays that are easier to control and exploit. Nonetheless, the need to reconceptualize comic book stores to accommodate these new enthusiasts suggests that the barriers to comic book fandom are being eroded.

[4.15] Although Harley Quinn Day may be seen as a calculated attempt to exploit fans, it was also explicitly identified by many of this study's respondents as prompting them to visit a comic book store. One female fan noted, "Being a big comic book nerd as well and having not been to a comic book store in ages, [Harley Quinn Day] was just a huge pull because it's a lot of things that I loved all combined together" (R14). Many respondents remarked on the mix of Harley Quinn fans in the store that included women, children, and male fans crossplaying as Harley Quinn, which contrasted with the reputation of comic book stores as a boys' club. One female attendee who described how comic books were once "aimed at males" credited Harley's multiplicity for the event's eclectic mix: "[It is] because of the diversity, the range of outfits, and also the age range from the animated children's series to comics for the older kids and to adult level as well" (R15). As this example suggests, the carnivalesque nature of Harley Quinn helps to elicit a "free and familiar contact" among people, which Bakhtin identified as the heart of medieval folk carnivals, but until recently had often been absent from rigid comic book fandoms.

[4.16] Lamerichs notes of cosplayer identification that "by stating that a narrative or character is related to me…I make a statement about myself. There is transformative potential in this ability to express who we are through fiction" (2011, ¶5.4). Not all Harley Quinn fans are guided by transformative intentions; nor do they share the same reason for adopting the character's persona. However, Harley Quinn cosplay offers many marginalized fans a means to signal their fandom. This "semiotic resistance" (Fiske 2006, 7) to what has traditionally constituted a comic book fan has proven successful in transforming comic book culture's strict hierarchies, including the once impenetrable comic book store.

5. The transmedia disruption of the comic book source text

[5.1] Suzanne Scott partly attributes a rise in female comic book readership to "comics' integration into transmedia storytelling models" (2013, ¶2.7). Indeed, the majority of this study's respondents described how audiovisual versions of the characters brought them to comic book fandom. Despite the wider visibility of adaptations of these characters, fan and nonfan audiences alike still often place an emphasis on fidelity to the comic books. For example, in my earlier study of comic book movie audiences I found that 89 percent of fans and 65 percent of nonfans considered it "moderately," "very," or "extremely" important that a comic book adaptation is faithful to its source (Burke 2015, 136–39). This emphasis on fidelity has seen some enthusiasts invoking a comic book urtext to demonstrate their fan credentials, including some of this study's participants. One male fan who felt it was "unfortunate" that his favorite version of Harley Quinn was from the film Suicide Squad quickly added, "I know some of the original comic series" (R2). A female fan who preferred the video games qualified her response by stating, "But I do love her in the comics as well" (R13). Thus, while adaptations of comic books to other media have brought a wider audience to these characters, fans still often treat comic books as a more authentic version and are critical of any perceived variations from this source text. Such fidelity discourses position comic books, and by implication their readers, at the center of comic book fandom. This section explores how Harley Quinn's introduction in an animated adaptation, rather than a comic book, provides a carnivalesque disruption of the comic book's privileged position in transmedia networks.

[5.2] The focus on fidelity in the responses of this study's participants is not unique to comic book adaptations but commonplace whenever adaptation is discussed. Drawing on Bakhtin's concept of dialogism in his analysis of adaptation, Robert Stam argues that critics need "to be less concerned with inchoate notions of 'fidelity' and to give more attention to dialogical responses" (2000, 76). Harley Quinn epitomizes a more dialogic mode of adaptation because the antihero is not a comic book character but was created for a television adaptation, Batman: The Animated Series. It was seven years after Harley Quinn was first introduced that the character was reverse engineered into the official comic book continuity. I have previously described the process in which an adaptation influences the serialized source text as "fidelity flux" (Burke 2015, 20). By becoming retrospectively faithful, the character of Harley Quinn provides a carnivalesque disruption of fandom by short-circuiting tired fidelity debates that position comic books as the unquestioned urtext in comic book culture.

[5.3] Applying Gérard Genette's transtextual relations, Stam describes adaptations as hypertexts "derived from pre-existing hypotexts." Accounting for heavily adapted sources such as the novel Madame Bovary, Stam suggests that the "diverse prior adaptations can form a larger, cumulative hypotext that is available to the filmmaker who comes relatively 'late' in the series" (2000, 66). In a further example of the free and familiar exchange Bakhtin identifies in the carnivalesque, Harley Quinn fans often contribute to the character's cumulative hypotext with amateur versions such as cosplay found to shape the source material. When interviewed for this study, Batgirl writer Hope Larson noted how some comic book characters who have proven popular with cosplayers have been reworked to make them more amenable to fan practice: "I definitely think costumes being cosplayable is a factor. It's probably part of why we saw so many Harleys this year [2016], is that they redesigned her and she's very easy to cosplay. You can find all those elements of that costume pretty easily. You don't have to have amazing sewing skills and make this crazy spandex thing."

[5.4] As Larson noted, responding to fan interest in cosplay, DC Comics have emphasized Harley Quinn's achievable aesthetic in recent updates, with the character found cobbling together her costume in a fan-like manner. For instance, as part of DC Comics' "The New 52" reboot, Harley Quinn is depicted making up her costume from mismatched hockey player socks, a jogger's shorts, a sex worker's bustier, a pawnshop's mallet, and a fast food worker's clown costume (writer: Matt Kindt; artist: Neil Googe, 2013). In a carnivalesque inversion of genre conventions, this do-it-yourself approach to costuming contrasts sharply with more established heroes who cover their bodies with alien cloth and ancient armor. DC Comics' acknowledgment and incorporation of fan versions of the character further dissolves any hierarchy that would position comic books as the automatic urtext in comic book culture.

[5.5] Although the reworking of superhero costumes to make them more cosplayable may demonstrate fan influence, like Harley Quinn Day such strategies are also an example of media stakeholders attempting to control fan activity. Linked to Harley Quinn's redesigns was a trend in merchandise in which apparel for heavily cosplayed characters moved from T-shirts and baseball caps emblazoned with the character or their logo to items that the superhero could conceivably wear within the diegesis. For example, following the release of the film Suicide Squad in 2016, Harley Quinn merchandise and clothing became a favorite at counterculture accessory stores like Hot Topic, which sold "Puddin" chokers, "Daddy's Lil Monster" T-shirts, and other paraphernalia the character had worn in the film. As Paul Mountfort, Adam Geczy, and Anne Peirson-Smith observe, "Commercial conscription and other regressive social forces constantly threaten the heterotopian (or anti-hegemonic) spaces of cosplay" (2019, 11). Nonetheless, in order to exploit consumer interest, industry stakeholders first need to expand their practices to accommodate fan activity. These transformations include recognizing fan versions of a character alongside official texts in a transmedia network that includes but is not limited to the comic book.

[5.6] Traditional fidelity hierarchies maintained the privileged position of comic books and their readers within fandom, even while comic book intellectual property was being extended across multiple media platforms. Harley Quinn is not the first comic book character introduced in an adaptation before being incorporated into comic book continuity, but she is one of the most successful, appearing in multiple monthly comic books and many adaptations. Furthermore, fan versions often sit alongside more official incarnations in the character's cumulative hypotext. In keeping with the carnival's inversion of hierarchies, the many versions of Harley Quinn displace comic books as an urtext and allow enthusiasts who come to the character from any number of media platforms to have equal rights to the status of fan.

6. Challenging the superhero genre's limited representation

[6.1] In her introduction to Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation Carolyn Cocca argues, "You are more likely to imagine yourself as a hero if you see yourself represented as a hero" (2016, 3). I now turn to detailing how Harley Quinn's transmedia presence goes some small way toward redressing the limited representation of gender and sexuality in the superhero genre. This representation has helped a more diverse array of enthusiasts feel welcome in comic book fandom.

[6.2] In further examples of fidelity flux, Harley Quinn was not the only character developed for Batman: The Animated Series that was ultimately added to comic book continuity. Police officer Renee Montoya and supervillains Roxy Rocket, Nora Fries, and Phantasm also made the transition, while a sister show, Superman: The Animated Series, provided comic books with the villains Mercy Graves and Livewire. In addition to first appearing in adaptations, another trait shared by these characters is their gender. The eager adoption of these TV show characters by the serialized source text is indicative of the traditional lack of women characters in superhero comic books, which Scott believes has left female fans feeling "fridged," as "an audience segment kept on ice and out of view" (2013, ¶1.4). Harley Quinn was identified by this study's respondents as challenging this imbalance, with many fans highlighting the carnivalesque character's feminist credentials and queer sexuality.

[6.3] Although Bakhtin's analysis of the carnival did not have an explicitly feminist perspective, Stam argues that his work can be "seen as intrinsically open to feminist inflection" (1989, 22). More favorable scholarly analyses of Harley Quinn align the antihero with the intersectionality and pluralism of third-wave feminism. For example, Geczy and Karaminas link Harley Quinn's appearance in Suicide Squad to third-wave feminism because the "kinderwhore" look can "destabilize and reappropriate signifiers of misogyny" (2019, 176). In their article "Superheroes and Third-Wave Feminism," Curtis and Cardo describe how Harley Quinn is "exaggeratedly 'female' in her anatomical form" yet "defies gender expectations through her 'masculine' performance" (2017, 385).

[6.4] Renegar and Sowards note that third-wave feminism often "emphasizes multiplicity, ambiguity, and difference," adding that the contradictions "foster a sense of agency for some third wave feminist writers and their readers that enables them to understand their identities, diversity, and feminism on their own terms" (2009, 1–2). Although Harley Quinn's carnivalesque disruption of traditional gender roles would seem to tally with many of the tenets of third-wave feminism, it should be acknowledged that male creators introduced Harley Quinn and were largely responsible for the character's early stories. These creators were also working within a superhero genre that tended to cater to male pleasure, so the often sexualized presentation of the character's feminism cannot be accepted uncritically. Fans have demonstrated this critical distance, with Kate Roddy observing that instead of "viewing Harley Quinn as a product of gender ventriloquism, fans consider her to be a persona that is fully formed and already fan property, and they tend to produce psychologically realistic readings of her" (2011, ¶1.8). Indeed, while acknowledging that the character can be sexualized, many respondents described Harley Quinn's antiauthoritarian navigation of her complex identity as feminist and welcomed this perspective in comic books and related media. As one female fan argued,

[6.5] They opened [the film Suicide Squad] with [Harley Quinn] going, "I sleep where I want, when I want, with who I want." It's like she can be a sexual character but she's not sexualized. It's on her terms. So if someone hits on her and she doesn't want to, she will hit them with a mallet. My brand of feminism is all about choice, and it's giving women the choice to do whatever they choose to do, and you've got a character who's like, "I choose to be on my own. I choose to be bisexual, or pansexual. I choose to leave my abusive partner. I choose to dress provocatively. I choose my partners." I think that's an incredibly feminist message. I think it can get co-opted and just be booty for the male gaze, but there's not a lot that can't be. You can do that with Gloria Steinem if you wanted to. But, yeah, I absolutely think she's a feminist character. (R1)

[6.6] Perhaps recognizing an appetite for a stronger feminist voice in Harley Quinn stories, WarnerMedia has increasingly hired women to shape Harley Quinn on page and screen. The 2020 film Birds of Prey had a female director and writer, Cathy Yan and Christina Hodson, respectively, while the film's star, Margot Robbie, served as a producer. In comics, writer/artist Amanda Conner has been the key creator on Harley Quinn since 2013. In fact, it was during Conner's tenure that Harley Quinn's outfits became more varied and revealing, with Curtis and Cardo arguing that while Harley Quinn's "sexuality has been accentuated by her new look she is totally in control of it, making an important contrast with the earlier, less sexualized depictions when she was nevertheless in a deeply abusive relationship and very much controlled by The Joker" (2017, 284–85). The sex-positive approach adopted by many of Harley Quinn's growing roster of women creators helps to cement the third-wave feminism fans had already ascribed to the character. This depiction was embraced by this study's respondents, as it provided enthusiasts with much-needed female representation in the traditionally male-dominated superhero genre.

[6.7] While many fans celebrated the character's increasingly feminist portrayal, a number of this study's respondents also commented favorably on Harley Quinn's status as one of the most visible queer superhero characters. In most transmedia appearances, when Harley Quinn severs her ties to the Joker, she is found teaming up with fellow villain Poison Ivy. From its earliest depiction, this relationship has had a queer subtext, with fans romantically pairing or shipping these characters in fan fiction, fan art, and cosplay (Geczy and Karaminas 2019). Responding to fan interest in Harley and Ivy as a couple, DC Comics made this relationship canon in 2017, thereby providing superhero comic books with what one of this study's respondents described as "a very prominent lesbian couple" (R9). This depiction has begun to filter into the character's transmedia extensions, with the second season of the animated series Harley Quinn culminating with Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy committing to their romantic relationship.

[6.8] Stam includes "bisexuality…as a release from the burden of socially imposed sex roles" as one of the tropes of Bakhtin's carnivalesque (1989, 93). Indeed, this study's participants largely approved of Harley Quinn abandoning her role as the Joker's henchwench in favor of a same-sex relationship with Poison Ivy, with comments that included "We love Harley and Poison Ivy over Harley and the Joker" (R8); "[Poison Ivy] loves Harley—actually loves her—so she can definitely live without the Joker" (R13); and "Harley Quinn has been looked down on by the Joker before eventually breaking free, getting rid of her abuser and finding her identity" (R9). These responses support Geczy and Karaminis' argument that "Harley Quinn's fundamental appeal lies in her ability to expose the fluidity of gendered and sexed identities and their representations in popular culture and the everyday" (2019, 185). Indeed, one fan with a stated interest in "LGBTQIA representation" articulated the sentiments of many: "I think we're getting better sexual representation […] I think characters like Squirrel Girl, Ms. Marvel, Harley Quinn [have] all helped to gear [comic books] away from the male target market" (R1).

[6.9] The greater fluidity of Harley Quinn's canonical gender presentation and sexual identity has been embraced by fans, who extend the range of interpretations further through playful activities like crossplay. Crossplay (a portmanteau of "cross-dressing" and "cosplay") describes the act of cosplayers' performing characters of a different gender than their self-identified gender (Tompkins 2019). One male fan crossplaying as Harley Quinn highlighted the character's achievable aesthetic and relatable persona for his choice of costume: "It's Batman/Harley Quinn Day, and I'm not into Batman. [Batman] was always going to be more difficult because I'm not a millionaire orphan. So, looking at it feasibly and economically, Harley Quinn was always going to be the better option" (R9). Jessica Ethel Tompkins (2019) notes that some fans who crossplay as traditionally feminine characters describe feelings of disempowerment. However, perhaps owing to Harley Quinn's fluidity, this fan expressed none of these concerns: "I picked Harley Quinn not really thinking too much of me being a guy doing a female character" (R9). Stam argues that "Transvestitism [sic] per se is not necessarily progressive or feminist" but, citing J. C. Flügel, notes how it allows male clothing, which "underwent a kind of visual purification," to become more playful: "Carnival, in this sense, brings back the sartorial exuberance of an earlier, more festive time which allowed for the decorative, narcissistic, ludic aspects of male dress" (1989, 164). As this study's crossplaying participant suggests, Harley Quinn's fluid identity authorizes a "sartorial exuberance" in which fans can choose to be a Maiden of Mischief rather than a Dark Knight.

[6.10] Harley Quinn cocreator Paul Dini embraces the diverse fan interpretations that the character's textual multiplicity facilitates: "Anything goes as long as they have fun with the character. I see little girls carrying around those huge mallets, I see their dads dressed up as some version of Harley wearing a 'Daddy's Little Monster' T-shirt. It's all fun for me […] I feel that anybody can be Harley Quinn." The manner in which fans from a variety of backgrounds have gravitated toward Harley Quinn and then expanded the character's multiplicity through a range of interpretations is also regularly commented on in Harley Quinn's transmedia appearances. In the "Quinn-tessential Harley" (2016) episode of the animated series DC Super Hero Girls, Lois Lane reports that "Harley fever has exploded into HarleyCon," a fan convention that is attended by people of all genders dressed as Harley Quinn. In the comic books, the self-styled Gang of Harleys is made up of Harley Quinn fans from different backgrounds, including Harlem Harley, Bolly Quinn, and Harvey Quinn. Similarly, in a Harley Quinn Christmas comic written by Dini, the creator acknowledges how the character facilitates carnivalesque unity, with the story finding a diverse array of Gothamites dressing as Harley Quinn and interacting freely, with Dini explaining how he wanted "to show that anybody can kind of have that spirit, that it's not limited to being a 28-year-old blonde woman." Indeed, Harley Quinn's visibility in comic books and related media has not only helped redress the superhero genre's limited representation but also allowed a wider audience to see themselves as heroes and fans.

[6.11] The character of Harley Quinn cannot be an all-conquering panacea for the many forces that have shaped and often limited comic book fandom. Nonetheless, the popularity of this character was reflective of, as well as active in, a widening comic book culture. As I have shown, these carnivalesque transformations include highlighting alternative pathways into the comic book fan community, resituating the privileged position of the comic book, and addressing the superhero genre's limited representation. This more open comic book fandom was perhaps most clearly acknowledged in Harley Quinn's elevation from sidekick to superstar.

7. Conclusion: From sidekick to superstar

[7.1] The transformation of comic book fandom is reflected in, and in some ways shaped by, Harley Quinn's emancipation on page and screen. Tony W. Garland has charted how Batman villains have a fannish interest in the Dark Knight. He notes that these criminals "could have fixated on anything, but the dark, brooding and obsessive Batman is almost irresistible." Garland identifies the Joker as "Batman's biggest fan," adding, "More than just the antithesis of Batman, the Joker has endured because of his fan dynamic with Batman" (2013, 127).

[7.2] In many versions, Harley Quinn is not depicted as a Batman villain or even a fan. When Harley Quinn has the Caped Crusader dangling above certain death in Mad Love, she explains, "For what it's worth, this really ain't a personal grudge. Y'see, I actually enjoyed some of our romps." Nonetheless, Harley Quinn does demonstrate some of the fan-like fixation Garland identifies, but her attention, at least in early depictions of the character, is directed toward the Joker. The distorted dynamic of the classic Harley/Joker relationship has echoes of fandom. As detailed in Mad Love, Dr. Harleen Quinzel's attraction to the "glamour" of "super-criminals" prompted her to intern at Arkham Asylum, where, like a fan attending a comic book convention, she was able to narrow the boundaries between herself and her object of interest—a boundary she literally and figuratively smashes when she creates the persona of Harley Quinn.

[7.3] As a number of this study's respondents made clear, Harley Quinn's relationship with the Joker is regularly portrayed as abusive, with one female fan articulating the sentiments of many: "I think her relationship with the Joker is incredibly problematic, and I think it's definitely an abusive relationship" (R1). Despite their concerns, many respondents felt that Harley Quinn's blind devotion to the Joker, which was often articulated through fanlike activities, made the character more relatable. For example, one female cosplayer described how the pairing is "relatable for a lot of girls who have been in abusive relationships, and it's really nice to watch her grow from that abusive relationship into her own person, which is why I really like 'The New 52' Harley" (R14) (note 5).

[7.4] Indeed, as Harley Quinn became more popular, the character was increasingly uncoupled from the Joker in most transmedia iterations. For example, the 2020 film Birds of Prey, appropriately subtitled "The Fantabulous Emancipation of One Harley Quinn," opens with the couple separating and Harley Quinn announcing that she needs "a fresh start, a chance to be my own woman." There was a belief among this study's respondents that Harley Quinn's growing independence from the Joker was a shared victory for Harley Quinn and her most devoted audience, with responses including, "You've seen a woman who's gone from being a psychiatrist to being a maniac and in an abusive relationship, and now […] she's living her own life […] it's like a really normal story, if you take all the superhero stuff out of it" (R1).

[7.5] This study's respondents celebrated Harley Quinn's carnivalesque disruption of superhero genre conventions and eventually the subservient role of henchwench for which she was originally created. Fiske challenges accounts that describe "carnivalesque pleasures" as "merely safety valves that finally serve to maintain the current structure of power" by contending that "these arguments fail to…[account for the] potential connections between interior, semiotic resistances and sociopolitical ones" (2006, 9). Indeed, Harley Quinn's carnivalesque destruction of boundaries has provided a road map for previously marginalized fans seeking to transform comic book fandom. From Harley Quinn Day to greater representation in comic books, attempts to contain Harley Quinn and her costume-clad fans have compelled stakeholders to widen the boundaries of comic book culture. These stakeholder strategies may be seen as an opportunistic attempt to exploit an avid audience; however, as Raymond Williams noted, in order to contain pressures, hegemony cannot "passively exist as a form of dominance" but must function as a nimbler "lived hegemony" (1977, 112). In fact, Harley Quinn's cocreator, Paul Dini, notes how the sidekick version of the character that he first introduced in Batman: The Animated Series is no longer tenable: "If we were going to do a new series, I wouldn't want that relationship to be the same. I feel that she's evolved beyond that, and I feel that she's more of an equal when she's with the Joker now rather than subservient."

[7.6] Harley Quinn's emancipation is reflective of how the character's fans and, subsequently, industry stakeholders have used the carnivalesque character to help transform comic book fandom. As I illustrate here, these transformations include providing new pathways into the comic book fan community, shifting comic book fandom's central axis away from print comic books, and allowing for more diverse representations of gender and sexuality in superhero stories. Although this emancipatory spirit has not broken the boundaries of comic book fandom, it has transformed them, helping to realize a more open comic book culture, where anyone can be a fan because now anybody can be Harley Quinn.

8. Acknowledgments

[8.1] This research was conducted as part of the Australian Research Council Linkage Project Superheroes & Me. I thank the supportive staff at Supanova, Oz Comic-Con, AMC Expo, and All Star Comics for facilitating this audience research. Thank you to my colleague Dr. Joanna McIntyre for her essential feedback and Tara Lomax for her assistance with this audience research, as well as to the many fans and creators who generously gave their time and shared their opinions.