1. Introduction

[1.1] Lori Morimoto: In practical terms, the 2018 Japan fan study trip arose out of a casual conversation between Louisa Ellen Stein, E. J. Nielsen, Paul Booth, and myself at the 2017 SCMS conference in Chicago, which basically began, "Wouldn't it be cool if…," and ended, "Let's do it!" In pedagogical terms, however, it's something I had been mulling over for several years as a result of witnessing a seemingly unbridgeable divide separating scholarship on Japanese popular culture on the one hand and fans and fandoms on the other. Mark McLelland (2018) has written about the challenges that existing fans of Japanese popular culture bring to increasingly "convergent" Japanese studies classrooms; similarly, the Japan fan studies tour was driven in part by the growing presence of such fans in mainstream media and media fandom classrooms and the challenges they present to instructors unversed in Japanese popular culture. Simply put, it was my hope that experiencing Japanese popular culture firsthand would give media studies faculty the basic knowledge needed to address these students' interests.

[1.2] At the same time, the Japan fan studies tour was equally intended as a means of affording participants the opportunity to make connections between their own research and aspects of popular culture that are seldom addressed in mainstream fan studies (and effectively marginalized when they are), as part of my own broader interest in transculturating fan studies. There's a scene early in the NBC TV series, Hannibal (2013–15), in which serial killer-cannibal Hannibal Lecter imitates the style of another serial killer in order that the contrast between his copy and the original might help illuminate the other's patterns and tells. It was this kind of contrast I hoped would be of use to participants in the tour, particularly where heretofore familiar objects (theme parks, film franchises, etc.) were experienced in unfamiliar contexts. Given what participants in the tour have written here, I could not be more pleased with the outcome.

2. Context is everything

[2.1] There was a heady mix of familiar and unfamiliar cultural elements and iconography on the trip. Only one participant had been to Japan prior to the trip, although all of us were familiar in some ways with aspects of Japanese popular culture (through our own explorations of transcultural fandom). Yet, seeing familiar icons of Japanese popular culture taken out of our immediate context and thrust back into their original context was, perhaps, the most unfamiliar of all. Our own Anglocentrism was reflected back on us.

[2.2] Ross Garner: What stood out to me were the differences in terms of how fan consumption is positioned and appropriated by institutions, and the effect this had on performing being a fan. Looking back I feel a little bit sad that I didn't quite have the time to prepare myself as fully as others for the trip and experience. I came straight from teaching to flying out and then being in Japan, and I wish I'd had more time to research a little bit about where we were staying in Shinjuku. Seeing the Godzilla hotel blew my mind (as someone who's currently researching fandom for prehistoric mediations), and learning that this area of Tokyo specifically branded itself via associations with Godzilla was incredible. Had I known, I'd have set aside a little time to try and meet with people and research this in more detail from an ethnographic point of view. In terms of what made it feel like home, that Rebecca and I went to Tokyo Disneyland on the Saturday really brought this into focus. This place should have been quite familiar as we've visited the Florida and California parks before. To say this wasn't the case was an understatement! The first thing I remember noting was the character headwear that many of the visitors had on. However, the parades seemed so much more elaborate than those that we'd seen before (I'll never forget the giant Baymax!), and the merchandise was very, very different in that there was less focus on the branding of individual attractions (as is the case in Florida) and more on the park itself and the Fab Five Disney characters.

[2.3] Bethan Jones: I did a lot of research before I went to Japan but more on what have historically been termed highbrow rather than pop-cultural objects. I was really interested in art and finding the best museums and galleries to visit. I also wanted to find street art and skate culture, so I spoke to friends who had visited Japan previously and did a lot of internet searching. There were specific prefectures I wanted to visit, and I spent a day on my own wandering around and looking for graffiti and alternative stores and spaces. I found a couple of amazing shops selling goth and punk clothes—spaces in which I find myself at home—and also found one store where the owner spoke English, had lived in the UK for a while, and had visited Cardiff! It was a slightly surreal experience—you don't expect to find someone so far away who knows your closest city—but it brought home the similarities as well as the differences.

[2.4] Garner: Can I also just mention tea in a can. It was simultaneously different and homely, and it instantly made me fall in love with Tokyo even more!

[2.5] Louisa Ellen Stein: Oh, tea in a can, how I miss you! That was one of my first discoveries, off the plane, and yes, it was love at first vending machine (figure 1).

Figure 1. Tea in a Can. Photo courtesy of Louisa Ellen Stein.

[2.6] Stein: Seriously, though, I was so excited when Lori began to plan this trip because over the past decade, I'd been becoming more and more deeply a fan of Japanese media and of anime specifically. I'd started as a high school student with Sailor Moon, but it wasn't until I started showing my daughter magical girl anime (Cardcaptor Sakura, for starters) that I became more fully immersed—and a Crunchyroll subscription pushed us both in more deeply. I'd also been trying to learn Japanese —with not much success—and had been reading translated work of Japanese fan/otaku studies scholars. So going to Japan with a group of fans/fan studies scholars was pretty much a dream come true. But of course consuming (mostly animated) representations of a fantasy Japan is very different from actually being in Japan.

[2.7] Stein: Initially, I felt some strange and exciting dissonance—things that felt niche and marginal at home in Vermont were everywhere, and things I experience as subcultural at home seemed on the surface mainstream in Tokyo, although I'm very aware that as a new tourist, I was of course missing many nuances and gradations of culture and subculture. But the presence of anime images everywhere, not to mention the wondrous supply of stationary, ramen, sushi, Muji, and Uniqlo did make me feel at home, even as it was strange that I didn't really have to go out of my way to seek them out. I remember standing on a train that was plastered with Detective Conan posters (another favorite of mine, as a long time Sherlock Holmes fan) and feeling just how surreal it was that this thing I had always experienced as obscure was everywhere (figure 2).

Figure 2. Detective Conan on the train. Photo courtesy of Louisa Ellen Stein.

[2.8] Stein: And certain things seemed to click into place—the beginnings of new understandings that came out of being in the spaces—like being in Animate and moving through various sections that had mainstream merchandise (which would have been not at all mainstream in the United States), and then through the areas filled with moe imagery, and then yuri, and then yaoi, and all the cases and cases of dōjinshi (fan-published comics). The endless amounts of dōjinshi for everything from Yuri on Ice to Hetalia to Sherlock left a very deep impression on me. It was a lot to take in.

[2.9] Jones: It was a lot to take in! I was so grateful to be with this group of people though. Not just because we all study fandom so could talk to each other about things we were experiencing and how we were theorizing them but because we are fans ourselves so I didn't have to feel yet another form of outsiderness—if I'd done this trip with nonfan friends, I think it would have felt very different. The language was one of the big barriers for me, and I was glad to have Lori there and to spend time with her. I tried learning—not very well!—but one of the things that really sticks out is when we went to have lunch in Kyoto one day. We found a place which had an English and Japanese menu and one of the dishes was chicken with Welsh onions—otherwise known as leeks! Of course that made me happy. I was also wearing my Kojima hoody (bought because Norman Reedus, who has worked on the Death Stranding videogame made by Hideo Kojima, owns one, and I'm a fan) which caught the attention of two women sitting next to us. I understood enough to know they were talking about the hoody but not enough to understand the context. Turns out Kojima is a big brand in Japan, but Lori also taught me how to say I've got it because of Hideo Kojima, a videogame developer.

3. Pedagogy and scholarship

[3.1] Our first stop in Japan was a symposium at Sophia University: "Intersections: Japanese and Western Fan Studies in Conversation." Our dialogue at the symposium helped develop new connections between Japanese fan studies scholars and Anglo fan studies scholars working on similar topics: audience studies, fan tourism, theater fandom, and manga readers (note 1). Our intent was to bridge the great Pacific divide and bring both groups of fan scholars into conversation about pedagogical and scholarly concerns. Similarly, finding aspects of fan work helped develop new avenues into our research, like our conversation with Professor Rachel Thorn about the history of manga.

[3.2] Melanie E. S. Kohnen: While we had many informal conversations about fandom and fan studies during the trip, I also found it helpful to discuss ideas at the Symposium at Sophia University, in a more formal setting.

[3.3] Stein: It was exciting to come together with scholars studying fandom from such a range of perspectives and contexts; our group itself brought together different foci and institutional contexts, and to engage in a day long dialogue in turn with Japanese scholars of fandom highlighted continuities and opened up new perspectives for me. I was especially fascinated by Akiko Sugawa-Shimada's presentation on "Female Fandom of 2.5-Dimensional Theatrical Performances." I hadn't heard the term "2.5-Dimensional" theater before (that is, theatrical production based on anime) nor realized what a strong tradition it is, with thriving transcultural fan practices; now I am absolutely intent on attending a production on my next visit to Japan. Another highlight was visiting Professor Rachel Thorn; she welcomed us into her office, spoke about her research and translation work, and shared with us her collection of early shōjo manga and yaoi manga magazines.

[3.4] Paul Booth: Yes, Dr. Thorn's presentation was a highlight for me as well. As someone almost entirely unfamiliar with manga, it was eye-opening to see how it had been developed since WWII. I was particularly invested in the way manga developed into girls' manga and boys' manga and the highly stratified reading environments of the 1960s and 1970s. This is something else I've been able to bring into my teaching, as many of my students are highly invested in manga and anime.

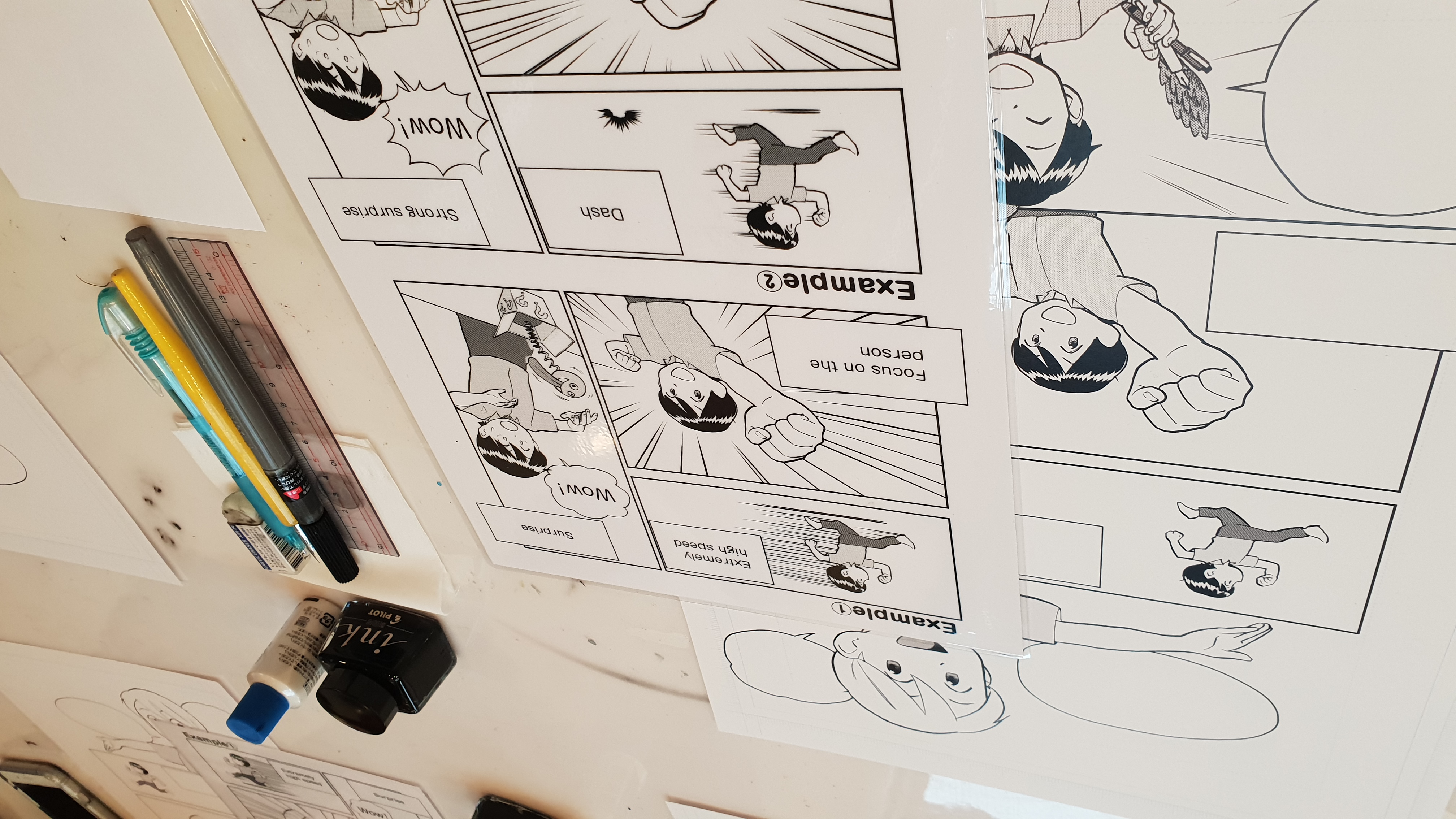

[3.5] Jones: Dr. Thorn's talk was so interesting, especially coming off the back of our visit to the Manga Museum and our attempts at drawing manga ourselves (figure 3)! I haven't read any manga but there are certainly works I'm adding to my list now.

Figure 3. Drawing our own manga. Photo courtesy of Bethan Jones.

[3.6] Booth: It's the pedagogical connections that were the most important for me. It's one thing to read about Japanese popular culture, or to see it in videos and documentaries, but it's entirely different to experience it firsthand. A lot of what I do in my classes is ethnographic work, and bringing in images and ideas from the trip has benefited my courses on fandom, popular culture, and technology. One example really stands out: in reading about Japanese fan cultures, it's clear that the Akihabara district is a mecca, of sorts, for collectors and fans of Japanese media, classic sci-fi, technology, and more. But actually going to the district and wandering around a twelve-story building and among the glass cases filled with action figures, dōjinshi, and costumes made real the practices that one only reads about. I can bring that into the classroom in a more visceral way than simply having students read about it. But at the same time, this shines a light on other transcultural fandoms—we can discuss how fans from other countries or cultures might view US fandom and fan cultures simply by the remnants of our culture. I've found that students respond to this reflective teaching strategy by opening up about their own tunnel vision when it comes to metacultural analysis.

[3.7] Stein: I want to second what Paul's getting at here: increasingly I am incorporating a wider diversity of media into my courses, including anime, and teaching about transcultural fandom. This trip without question helped me think about transcultural frictions in new, more tangible ways, and that's something I will bring into my classroom discussions as I encourage my students to think about their own location and experiences within transcultural fan frameworks.

[3.8] Rebecca Williams: For me, I think I would like to be able to draw on the experiences a little more in the classroom, but in the UK system I have limited chances to do that. I've talked a little about the differences between cultural experiences of fandom before in class, and I think if anything, this trip gave me more confidence in being able to want to address some of that. It's hard to step outside of the dominant Anglophone white middle-class experience, especially with students who are usually from pretty homogenous backgrounds, and I hope that the experiences from the trip will continue to make me feel like we can challenge our own experiences, and that I can continue to push my students outside of their own comfort zones as much as possible.

[3.9] Kohnen: So far, the only thing I've incorporated is the Captain Marvel promotion I noticed/photographed in Tokyo (and the mini-poster I got at the pop-up Marvel store in Narita). I tracked the promotion of Captain Marvel in a class last spring, and it was helpful to include examples from Tokyo to show Marvel's global reach, especially because the promotional material didn't look different from what I encountered in, for example, Times Square.

[3.10] Garner: In terms of scholarship, as a result of the trip, I've reconfigured my monograph manuscript to be solely about how Saban Brands has rebooted the Power Rangers (1993–96) franchise via nostalgia. Although there's not the time or space to address this overly in terms of transcultural debates, it's certainly brought me an additional angle for thinking about how intergenerational nostalgia migrates between different areas (and Pokémon can sit very well with that as well).

[3.11] Williams: I've been working on a chapter on fashion and clothing in themed spaces and talked a bit in that about the differences between Disney and Universal theme parks in the United States and what I saw in Japan. I would never have considered thinking about that without the firsthand experience of seeing how people dressed and how that mapped onto the idea of kawaii culture and cuteness in Japanese culture more widely. I ended up reading a lot about the history and development of kawaii for that chapter, and I really hope I can do some more comparative transcultural work in the future.

[3.12] E. J. Nielsen: While I haven't yet been able to incorporate anything from the trip directly into my scholarship, it was an important reminder for me of all of the incredible work being done by non-Western scholars that for various reasons (access, language barriers, Western-centrism in scholarship, straight up racism) we aren't always aware of and that I need to make more of an effort to seek out. Dr. Thorn did a fantastic job of giving us an overview of the history of women's manga, and the presentation by a senior scholar on his efforts to have manga, dōjinshi, and related merchandise archived by the National Diet Library was incredibly interesting to learn about, especially in the context of work I'm doing on material object culture and fandom. He argued that the merchandise is so much a part of the text that to archive the text without it is to destroy necessary context. More broadly, seeing Japan with a group of fan studies scholars who were themselves also fans meant being simultaneously unselfconsciously letting our fan flags fly while also being able to take critical steps back and look and discuss more broadly what we were seeing and experiencing. I can't imagine a better group to travel with.

4. Bringing and seeing fannishness in Japan

[4.1] Everyone in the group had their own fannish interests, but most of those interests center on Anglo-American media. Throughout the trip, though, various manifestations of these fandoms appeared in Japanese contexts, highlighting the ubiquity of transcultural fandom. In particular, the idea of space dominated our thinking about our own fannishness.

[4.2] Kohnen: I've been interested in San Diego Comic-Con (SDCC) and its spaces for a few years now, and I've written about how fans conceptualize and discuss the space of the convention center and the surrounding downtown area. It was striking to go to Akihabara and Otome Road and see how strongly gendered these fan spaces were. Even though we encounter gendered spaces all the time, I had not had that experience in terms of fannish spaces before. At SDCC, there might be single booths that may sell merchandise targeting traditionally masculine or feminine fan interests, but those booths still appear next to one another. The idea of separate neighborhoods that are quite far apart geographically was eye-opening.

[4.3] Nielsen: It was fascinating to visit Universal Studios Osaka (since I am familiar with the Florida park) and see the differences and similarities in how the experiences were constructed for different (US and Japanese) audiences. It made me think about how both American and Japanese audiences approach otherness in media. For example, the JAWS ride (RIP Florida JAWS ride, you are missed) featured a young Japanese woman as our captain, and her narration was entirely in Japanese. However, everything in the Wizarding World of Harry Potter (WWHP) section featured white, costumed performers speaking first in English with British accents, then following that with Japanese translations of their speeches. It was clear that in the park, the magic experience and aesthetic of Harry Potter is tied in with the exotic otherness not just of a fictional Wizarding World but of a real (white) Great Britain. This is in contrast with JAWS, which is set in the far-off space of New England, a place also full of white people speaking English but that the park did not feel the need to recreate through language and race, or Jurassic Park, which while still a fantastical setting was also not explicitly signposted as other. This use of language as an exotic aesthetic in the creation of a fantasy setting is especially interesting; the closest US equivalent might be the World Showcase in Disney's Epcot, but there the spaces being recreated are real (albeit heavily stylized) places. The Florida Universal Studios does use performers with British accents in the Wizarding World, but I can't imagine a US park foregrounding a language other than English even if it were thematically appropriate. US audiences seem to view English as such a default that we expect it in all settings and would be more likely to feel excluded than magically transported by the use of another language.

[4.4] Williams: I was also interested in the differences in the theme park spaces I visited, both Universal Studios and the Disney parks in Tokyo. Guest behavior was very different to that in the North American and French parks I have visited; there was a much more controlled use of space, people were more polite, and the fannish behaviors common in the Western parks were either missing or quite different. The ways that people dressed or Disneybounded as characters was interesting since it seemed to draw on an established style and the idea of kawaii culture as much as it utilized clothing and accessories from the parks and from the Disney and Universal brands themselves.

[4.5] Nielsen: Absolutely. I loved people-watching in the theme parks. Couples or groups would match or coordinate their outfits in ways I haven't seen in US parks, sometimes in ways which were clearly performative but not directly related to the park itself. For example, I saw a number of younger couples performing couplehood through matching outfits. But there were also park-themed outfits, including Minions kigurumi and Minions-bounding at Universal.

[4.6] Stein: To build on what others have said about WWHP, I bought my five-year-old son a wand from Ollivanders Wand Shop in Osaka as a souvenir. The wands from WWHP come with maps of the park indicating where you can perform spells. But of course the maps are specific to each park, and I found it fascinating when I got home to spread out the one from Osaka beside the one from WWHP in Orlando, Florida, where both my and my daughter's wands come from, to see the same shared space mapped across different geographical and cultural contexts. WWHP Japan was both familiar and distinct in such a striking way. I felt at home both in the fantasy world being created and because of my previous experiences of WWHP Orlando but also experienced it as something new. This was accentuated by my (excellent) company—it was wild, I have to say, to be at WWHP with a group of fan studies scholars and fellow fans who were simultaneously analyzing and embracing the experience together.

[4.7] Booth: I don't think I speak for everyone here, but finding the gashapon machines totally cemented my understanding of how fandom and popular cultures can be transcultural. Gashapon machines sell little toys in bubble-like containers—you've probably seen them in supermarkets selling tiny trinkets for a dollar. But it's a whole order more impressive in Japan, where gashapon machines are found on most streets and overflowing in malls. Entire rooms are devoted to them, and some of the things in them could be rather expensive—five dollars for some of the more adult items, for instance. But what I found most connective to my own fan experience is the commodification of collecting. Most gashapon machines randomize what you get from a selective group—so there may be ten different Shiba Inu models in different poses, but you never know which one you'll get. This encourages consumption and a collect-them-all mentality, much like a recent American focus on blind box purchases of action figures. At the same time, many gashapon machines don't even sell what we might traditionally call cult objects—I remember Ross on the hunt for the elusive five-foot model of a tuna fish in a gashapon, and I found the everyday office supplies gashapon fascinating (a tiny stapler! A tiny file folder! A tiny tape dispenser!). This definitely linked to my own love of fannish collecting and the game of trying to find that one piece that you're missing.

[4.8] Garner: About the gashapon: this really kicked in my OCD, I'm afraid to say. (I don't use the term OCD in an offhand or derogatory manner here; I actually suffer with OCD.) There seemed to be very interesting franchise mash-ups within these collections, and the chief one that caught my eye was the Minions-as-Universal Monsters range. We only saw these once, and the machine was jammed, so I always went to where they had dispensers to see if this collection was there. It was only on the very last day in Osaka airport, where there was a dedicated area introducing gashapon to non-Japanese tourists, that I found this particular range again. However, the scope of different properties that were represented and the different takes on characters and character aesthetics made it like a hunt or a quest to try and find what you were looking for.

[4.9] Garner: But, for my Jurassic Park fandom, Nakano Broadway was a real find. I distinctly remember that there was a specific retailer that had multiple outlets across each of the floors—some seemed to be specialist for specific franchises like Disney, Super Sentai, or Marvel while others were more general—and it became a case of trying to identify (and then remember) which one had the broader content where Jurassic Park goods were stocked. There wasn't much in the particular outlet, but I remember being surprised—and as someone who studies licensing I shouldn't have been—that there was a replica of the Park Explorer jeep (the green one from the tour) there. The movement of this item from mass-produced merchandise to fan collectible in the UK is fairly normative (see eBay for example) but seeing it in Nakano Broadway seemed to add additional meaning to it—perhaps as a potential souvenir?

[4.10] Garner: Alternatively, at Universal Studios Japan I was struck by the extent to which there seemed to be an emphasis on linking Jurassic Park to educational/natural history discourses to an extent that is absent at Universal IoA in Florida. For example, there was a parade of dinosaurs that moved through the themed space that was accompanied by a Japanese actor (dressed similar to Alan Grant) who was giving out information about the dinosaurs. Secondly, in the shops there was an emphasis on collectibles that could either extended the franchise's boundaries (e.g. you could buy boxed fragments of dinosaur bones or teeth) or placed an emphasis on building (e.g. the JP Park Gates). The key point is that there were a lot wider points for being a fan than only plastic dinosaurs, vehicles, or T-shirts with the JP logo emblazoned across them (although these were also there).

[4.11] Stein: One of the things that really stood out to me was the bookcases of dōjinshi for Western media texts—Sherlock, Supernatural, Harry Potter, and others. It was a moment of recentering for me, seeing what I've experienced as central in Western fan culture here as niche, and not just niche but rather transformed into the aesthetics and narrative structures of Japanese dōjinshi traditions and practices.

[4.12] Williams: For me, the thing I came away with was becoming a fan (of a sort) of Pokémon which I had zero interest in before the trip. Visiting the Pokémon stores and the Cafe really made me interested in how the themed spaces worked, and now I have a favorite Pokémon, and I'm quite interested in certain aspects of the franchise. I remember, too, a trip to the Sega Cafe where customers who were clearly fans of a specific Japanese text were engaging in forms of what we'd likely consider fan pilgrimage or tourism; supporting their teams or character and taking important objects with them to the Cafe and placing them on the tables. It was really transformational for me to see how normalized that kind of fan activity was and also to be an outsider to what was going on, since we had no idea what fan object was being celebrated. I found that a really fascinating experience, even if at first it felt quite uncomfortable to be an outsider in that space.

[4.13] Nielsen: I spent some time in Japanese bookstores looking at dōjinshi and of course the sheer volume available was incredible, as was the variety. These are Japanese fans producing content for other Japanese fans, and it was fascinating to see what media, characters, pairings, and more are popular. Plus, of course, the strangeness of seeing fan comics, many of them very explicit, openly offered for sale in bookstores.

[4.14] Kohnen: I was also amazed by the dōjinshi selection in bookstores—as someone who is interested in copyright and remix cultures, it was exciting to see fan-authored texts and traditional publications in the same store. It was also fascinating to see which characters from American media texts like Star Wars or the Marvel Cinematic Universe featured prominently in dōjinshi.

[4.15] Garner: Yes to the Sega Cafe! I went from feeling completely out of my depth to gaining an appreciation for what was normative fan behavior in themed restaurants as a result of this happy accident. I'll remember that for a long, long time. I suppose I'd also say that about Pokémon. I played the games through an emulator in the late '90s/early '00s and enjoyed them and had also watched a lot of the early cartoons. The interest had waned over the years—likely associating it with growing up—but I've retained knowledge of the initial Kanto characters and saw visiting Japan as an opportunity to reengage with this; I'd marked visiting the Pokémon Cafe as a must do and also wanted to adopt my own Pokémon (my favorite has always been Jigglypuff) via visiting a Pokémon Centre (store). The fact that I narrate the latter act in terms that detach it from any sense of commercial underpinning probably says a lot! However, the way I performed my fan identity during the visit to the Pokémon Cafe was completely influenced by what I'd previously seen at the Sega Cafe. I proudly sat with Jigglypuff on the table as my/our mascot (as others were doing with their own), and it enhanced the experience by allowing affect for the franchise to coalesce with the newly acquired merchandise so that the character became a souvenir on many levels and of many events. I should also say that it was great to be travelling with another person who was a massive Pokémon fan as this helped to legitimate my interest and they got me playing Pokémon Go again. I'm still playing now!

[4.16] Stein: At lunch on the day of the Symposium, one of our fellow presenters, Yukari Fujimoto, who does work on shōjo manga, told me about a temporary exhibit for the manga and anime series Cardcaptor Sakura (1996–2000) at the Mori Arts Center Gallery. Cardcaptor Sakura is one of my very favorite series and was my introduction to the wonderful manga artist group Clamp. I dragged Melanie with me to the exhibit, though she didn't (yet) know Cardcaptor Sakura. As we were standing in line, I had this crazy thought—"they'll have Sakura's costumes!" Of course this made no sense, since Cardcaptor Sakura is an anime and there are no real costumes. Or so I thought. Because as it turned out they absolutely did have the costumes—they were indeed a key part of the exhibit. The clothes were stunningly beautiful, and it was wild and wonderful to see them in material, 3D fabric reality, which prompts all sorts of questions about my investment in and experience of the aesthetics, narratives, and characters of Cardcaptor Sakura. I was also moved by the exhibit's address of the series inclusion of queer romance. The exhibit read "The way Cardcaptor Sakura addresses love is slightly different from the way most girls' comics feature teenage crush-like feelings. As the relationships chart shows, the characters' relations with each other go beyond gender, social class, age, nationality, and ethnicity and are solely based on care for each other." I'd always felt this sentiment as I watched Cardcaptor Sakura, but to see it rendered here as something intentional and collectively shared changed my feelings about and understandings of the show. Not to mention the simple thrill of wandering through the exhibit with others for whom Cardcaptor Sakura was also meaningful and important, if no doubt in different ways than it was for me. (Plus, I got to have my picture taken with a gigantic Kero-chan.)

[4.17] Jones: I was also at the Sega cafe! And it was an odd experience to be the outsider in that fannish space. I'm used to attending conventions and the like in the UK and the United States, but the norms of fandom in those spaces are different to that of superficially similar spaces in Japan. What strikes me as really interesting listening to what everyone else has to say is that no one has mentioned the Studio Ghibli museum! This was a real highlight for me, having been a fan of Ghibli since a friend introduced me to Laputa: Castle in the Sky in the early 2000s, and to say I was excited when we got there is an understatement. Seeing the robot from Laputa on the roof when we were waiting to get in made me actually squeal with excitement in a very fannish way. There are obviously nods to the fandom and fan tourism in the way the museum positions itself—tickets are offered for sale once a month and are strictly limited; the bus that took us from the train station is bright yellow and branded with Ghibli characters; with the entry ticket you get a unique Ghibli film cell—but in many ways there also seemed to be a deliberate attempt to move away from the collectible nature of fandom and become immersed in the physical space of the museum. Once we were in the museum there were strictly no photographs allowed. On the one hand I could understand this because honestly, there were so many amazing things I could have taken photos of and having hundreds of people stopping at random to take a photo of something would have been a nightmare (the museum is pretty small); but on the other I know there are things I'll forget about the museum that I'd love to be able to look at, so not being able to take photos was tough. The one exception is on the rooftop garden where you can find a life-sized robot from Castle in the Sky and have your photo taken with it. Unsurprisingly there was a queue for this, but despite that and the fact I hate having my photo taken I stood in line, just so I could touch this incredible machine (figure 4).

Figure 4. Studio Ghibli Museum. Photo courtesy of Bethan Jones.

5. Beyond fandom

[5.1] It wouldn't be a fan scholars' trip to Japan without some geeking out about specifically nonfannish things. What were some of the nonfannish things we found most enjoyable?

[5.2] Morimoto: I'll say now that I had never once passed by Mount Fuji on the Shinkansen on a clear day like we had, and that really stood out for me (figure 5).

Figure 5. Mount Fuji from the Shinkansen. Photo courtesy of Lori Morimoto.

[5.3] Garner: Definitely Kyoto. The architecture, the accommodation, and the dining experience made it feel like another world. I really want to go back and spend more time there.

[5.4] Stein: Kyoto without doubt. Wandering Kyoto's Nishiki market and eating the most delicious takoyaki of my life, or wandering the back streets of Kyoto where our house was; it killed me to leave Kyoto after only a couple of days, and I want to find a way to spend a semester there in the future! Also conveyer belt sushi is pretty much my definition of heaven.

[5.5] Nielsen: I hiked part of the Fushimi Inari shrine at dusk. It was quiet enough at that time of day that there were often no other people in my field of vision, a contrast to the huge crowds we encountered in so many other places on the trip. The air was damp and cool, and the thousands of torii cast strange patterns of shadows in the growing darkness. The atmosphere was uncanny enough that I kept expecting to run into fox spirits (figure 6)!

Figure 6. Fushimi Inari shrine. Photo courtesy of E. J. Nielsen.

[5.6] Kohnen: I wish I had been there for the Kyoto portion of this trip! A stand-out experience for me was visiting the Cardcaptor Sakura exhibit with Louisa and eating at the themed cafe there. I didn't know anything about Cardcaptor Sakura before attending the exhibit, and I really enjoyed seeing other visitors' excitement at interacting with a beloved text. Also, the hot tea in cans from vending machines, as Ross already mentioned.

[5.7] Williams: I think the food! I'd always had a strong sense of what I imagined food in Japan to be like, and it did not disappoint. One of my highlights will be wandering into a traditional sushi place near Nakano Broadway and muddling through ordering and paying, being seated at the sushi bar while the chefs worked, and the dishes being prepared that I'd never seen before in a sushi restaurant in the West. I'm really glad we got the chance to experience that.

[5.8] Booth: Visiting Nara, the city where deer roam the streets freely and where a giant Bronze Buddha statue (at Tōdai-ji), was standout for me. Being able to walk among the animals, feed them little cookies and things (totally fine—they were for sale on the street) and then visit one of the oldest shrines in existence put our everyday concerns really into perspective. (Literally. The statue is so big [over 500 tons] that you have to be standing pretty far away to see it all.) Plus, I made best friends with deer (figure 7).

Figure 7. Deer in Nara. Photo courtesy of Paul Booth.

[5.9] Jones: There's so much I don't know if I could choose just one thing! The food, like Rebecca says, was incredible. Lori, E. J., and I went to Ninja Akasaka, a ninja-themed restaurant, which was just so much fun. We got to be ninjas in training and say a spell to raise a drawbridge, ate a ten-course meal of the most amazing food I've ever had, and had a sleight-of-hand magician entertain us. Of course, we chose to go there because Hideo Kojima took Norman Reedus and Mads Mikkelsen there when they were in Tokyo making Death Stranding, but we're fans—can you ever truly turn the fandom off?

[5.10] Nielsen: Then again, would you ever really want to?

[5.11] Jones: The other highlight for me, though, was wandering around Shimokitazawa with Rebecca and Ross. The streets were pretty quiet—though we were there relatively early and according to my research most places didn't open until 10 a.m. or later anyway. But there was so much street art! And vintage stores, art galleries, record shops, more art galleries. I think I took more photos there than possibly anywhere else on the trip (figure 8). Plus there was good weather and good friends—what more could I have asked for?

Figure 8. Shimokitazawa street art. Photo courtesy of Bethan Jones.