1. Introduction: "You call this archaeology?"

[1.1] It seems apt to begin with a quote from the Indiana Jones franchise—a film series about the adventures of a fictional archaeologist, which is itself an homage to classical Hollywood cinema—because this essay considers the connections between the fields of fandom, archaeology, and film history and how to explore what is at stake, in terms of access and agency, in the construction, dissemination, reception, and embodiment of histories. The paper is concerned with why history—and who has the means to tell it—matters. It does this by advocating the engagement of learners using an experiential approach borrowed from interpretive archaeology and by exposing them to a range of cinema artifacts (both recent and older) that reveal aspects of film and social history with a view to encouraging those learners to seek out and tell their own fannish histories.

[1.2] However, as anyone who has ever attempted to hold an academic audience's attention knows, eliciting enthusiasm and engagement is key to successful learning, and at times this is easier said than done. Sadly, we don't all have Harrison Ford's magnetic appeal. So how might a film historian such as I demonstrate to learners that history is for them?

[1.3] A stumbling block when facilitating learning around film history—or even history more generally—is that unless the facilitator is careful, the "material of teaching" (Moon 2004), can appear to the learner to be irrelevant to their prior life experience and therefore to their current learning encounter. Certainly, any field's essential theoretical, methodological, and contextual underpinnings can sometimes seem needlessly abstract to learners, presenting an "epistemological obstacle" (Brousseau 1983) to overcome in order to grasp these foundational ideas effectively. My concern as a film historian is that my learners will see history as past and therefore irrelevant. Indeed, they can initially seem dismayed when they learn that they will be using historic resources. Presumably these items will be dull, dusty relics. So, they are generally surprised—and swiftly engaged—when they are shown current film culture as historic artifacts, such as unanticipated, esoteric 80-year-old pornographic cartoons starring classical era film stars, or 60-year-old magazine articles featuring astonishing racism, ableism, and misogyny that—at first glance at least—wouldn't fly nowadays.

[1.4] This article proposes a means of evading these obstacles to engagement (and ultimately to learning) through a pedagogical technique based on direct contact with a range of specially selected cinema paratexts. It borrows, in part, from Gee's (2005) notion of the affinity space discussed previously by Booth (2018, 122–23), in which "learning happens through small-group work, student-teacher interactions, and peer contributions." In this setting, learners are encouraged to "critically engage in their own interests" and with a range of new and old fan objects in a range of ways, mixing the familiar with the less familiar.

[1.5] Encouraging learners to self-identify as fans, or at least encounter fandoms through direct, physical, even playful engagement with loosely grouped, cinema-related fannish objects—variants on dolls, types of magazine, or varieties of ephemera given away free in cigarettes or confectionary, for example—reveals to modern eyes commonalities as well as differences across decades and fandoms. It highlights to learners how the histories and ideas that these resources reveal could be relevant to their own lived experience. The subjectivity built into this approach offers a further benefit: providing learners with opportunities to make and see the value of their own interventions into history, developing their critical skills through reflexive discussions around how their specific prior experience (or relational and contextual frame) may affect their individual comprehension and interpretation of these artifacts. This realization is key to comprehending and ultimately mastering the broader epistemological principles of history as a discipline.

2. Theoretical, epistemological, and pedagogic frameworks: "We have top men working on it now." "Who?" "…Top…men."

[2.1] Throughout this article I will draw upon a theory of language, cognition, and learning known as Relational Frame Theory (RFT) (Haynes, Barnes-Holmes, and Roche 2001). Developed from B. F. Skinner's science of Radical Behaviorism and rooted in the philosophy of Functional Contextualism, RFT posits that learning is contextual. According to this theory, complex human behavior develops through learned relationships between words, ideas, and events. Sets of relations are derived in specific contexts, and individuals make complex meanings (functions) by relating sets (frames) of previously learned relations from similar contexts. So particular cues have particular meanings for individuals in particular contexts according to their prior learning history (or, in Bourdieu's [1984] terms, their habitus).

[2.2] An example of this phenomenon can be found in our familiarity with the conventions of film genres, such as the action-adventure narrative. Through prior filmgoing experience, we have expectations (contextual behaviors) of what such films and their narratives will offer: a plucky hero on a quest (let's say for a precious religious relic); a damsel in distress, for whom our hero falls; a bunch of bad guys (let's say Nazis) also looking for the relic, and lots of out-of-the-frying-pan-into-the-fire scenarios. For the purposes of this article, I draw upon this notion of learning as contextual and upon the concepts of context and framing by referring to a learner's contextual frame.

[2.3] In terms of educational methods, I am advocating the use of what archaeology refers to as an interpretive approach. This is to be applied by learners to a range of fannish primary resources. As archaeologists Shanks and Hodder note, the use of the adjective "interpretive" here is indicative: "Foregrounded is the person and the work of the interpreter. Interpretation is practice which requires that the interpreter does not so much hide behind rules and procedures predefined elsewhere, but takes responsibility for their actions, their interpretations" (1995, 4) (note 1).

[2.4] The focus upon interpretation and the interpreter lends itself well to fandom-focused pedagogies that foreground the subjective and learning through experience. While Geraghty (2014) discusses how students are often reluctant to talk about their fandoms in class, I always open my first workshop with a group by confessing a film-related fandom and subsequently asking learners if they will share something of which they are fans. For learners who find this question too personal or who struggle to identify something of which they are enough of a fan, reframing the question from "What are you a fan of?" to "Have you seen or experienced a fannish activity before?" helps considerably.

[2.5] Given Shanks and Hodder's (1995) remark regarding interpretive responsibility and the reflexive nature of this teaching/learning approach, it is germane to also consider the justifications and potential pitfalls of this pedagogical approach. It is also relevant to reflexively engage with these complications and limitations, considering how they might be anticipated, mitigated, appraised, and possibly even utilized to learners' and facilitators' ultimate advantage.

3. Academia, fandom, and inclusion: "Don't call me Junior!"

[3.1] The academy is exclusive: it is classed, racialized, ableist, ageist, and gendered. As scholars such as Bourdieu (1984) have amply demonstrated, access (to materials, histories, even learning itself) is linked to control and power. In a typical learning transaction, the learning facilitator will usually hold the knowledge, resources, and often the advantage. In Bourdieu's terms, when attempting to develop their cultural capital and facilitate their social mobility through learning, a learner is in many ways at the mercy of the larger system—a system that many academics, such as bell hooks (1994), Heather Savigny (2019), Nicole Brown and Jennifer Leigh (2018), Regina Day Langhout, Francine Rosselli and Jonathan Feinstein (2007), and Karen Kelsky (2012), have all noted is still beset with systemic racism, sexism, ableism, classism, and ageism.

[3.2] Fandom is also subject to boundary policing. However, historically fandom studies has worked to unpick prevailing cultural distinctions and, for example, systemic gender-based marginalization, acknowledging fans' diversity and agency (Busse 2013; Scott 2019; Hills 2002). Similarly, post-processual archaeology approaches, such as interpretive archaeology (tellingly, also known as the new archaeology) have also sought to depart from processual archaeology's primary preoccupation with the mainstream, the anthropological, and broader cultures, systems, and structures, toward a concern with nuances, individuals, and interpretation.

[3.3] Within film studies, disciplinary revisionism also prompted a shift away from broad historical sweeps to case studies recording the minutiae of film production, exhibition, and consumption. As Elsaesser notes, the advent of New Film History saw a movement away from "the surveys and overviews, the tales of pioneers and adventurers that for too long passed as film histories; and sober arguments among professionals now that, thanks to preservation and restoration projects by the world's archives, much more material has become available" (1986, 246).

[3.4] This larger methodological shift—to seek out and communicate narratives that reflect a more inclusive range of interests, experiences, and perspectives—is laudable and timely. History is about the telling of narratives, and who gets to tell those narratives matters. To have a voice is to have agency. To teach the methodology and the politics of history is to potentially provide individuals with the means to tell (and see the value of) their own stories. For this reason, the progression toward inclusivity should be constantly reflected in our teaching, but this is easier said than done. Educators don't know what they don't know, and learners may not have the inclination or skills to challenge and educate their educators. So how can a truly inclusive syllabus anticipate and address such gaps?

[3.5] Asking students to bring their fandom and its associated expertise into the learning space can offer this opportunity. In my experience, learners from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic backgrounds (BAME) have taken the opportunity to investigate specific cultural phenomena about which I, a middle-aged, white woman, may have little comprehension or awareness. The considered use of a fandom-focused approach can be far more inclusive of students' own contexts and concerns, more accurately reflecting and speaking to a diverse and multifaceted student cohort. It shifts the power balance, placing the learner in the position of expert. Suddenly, a workshop that may initially be perceived by the learner as obtuse or even dull becomes the workshop where they find—and can actively demonstrate—their oeuvre, test their skills in synthesis, and gain confidence, making for a more invested, lively, varied, and productive learning and teaching experience.

4. Familiarity, creativity, and investment makes for mastery: "Fortune and glory, kid. Fortune and glory."

[4.1] The engagement, comprehension, and eventual mastery of a resource, foundational or threshold concept, or broader field of learning come in stages. Playing with or examining an artifact and identifying its surface or denotative reading is merely the first stage of critical engagement. Beyond that, learners must progress to a more nuanced connotative engagement in order to achieve the required level of analytical skill. It is useful here to consider Sandvoss's notion of "heimat" or "home." As he observes "Fandom best compares to the emotional significance of the places we have grown to call 'home,' to the form of physical, emotional and ideological space that is best described as Heimat. Fans themselves often associate fandom with a sense of home…Similarly, fans…often refer to their fandom in terms of 'emotional warmth' or a sense of security and stability, which in turn are associated with Heimat" (2005, 64). This emotional significance linked with individual fandoms can be utilized to bridge the gap, to cross the threshold, if you will, between the familiar and the strange, in order for the learner to master the field.

[4.2] Furthermore, heimat's implications of safety and comfort, both of which are requisites for successful learning, raise another salient point: the need to remember that when encountering unfamiliar examples, learners can be inadvertently or deliberately derisory or dismissive about another's fandom. This actual or feared rejection and/or ridicule may mean that learners feel unsafe engaging with or sharing aspects of their fandom: it may simply be too personal. Here Hills's notion of fandom as "a form of cultural creativity or play" (2002, 90) is helpful.

[4.3] Engaging with history through a range of resources and in relation to a range of theoretical contexts in a playful, creative, and subjective way may, at first glance, appear to carry probable complications in terms of authenticity and objectivity, but as Shanks and Hodder observe: "Archaeology is…conceived as a material practice in the present, making things…of the material traces of the past, constructions which are no less real, truthful or authentic for being constructed" (1995, 4). This exploratory, playful approach can offer such potential, in terms of broadening access and increasing ownership and investment, that it warrants consideration, if only because of how creative the assessed presentations on my module often end up being. For one presentation entitled "A Part of Their World" that examined the psychological pleasures of Disney fan collector culture, I was banished from the presentation room and upon my return found the two presenters in full Disney regalia, with what appeared to be the entire contents of the Disney store laid out on the table in front of me and with a carefully selected Disney medley playing softly in the background in order to immerse me "in their world" (figure 1).

Figure 1. A student presentation on Disney fandom and fan collecting practices.

[4.4] I have been talked through a student's grandparent's film star cigarette card collection and a battered, 60-year-old film soundtrack LP collection, had a life-sized Marilyn standee emerge clumsily through the classroom door in readiness for a presentation on marketing Monroe's star persona to contemporary film fans, and had a pair of learners present on the social media promotion of actor Chris Evans and the Captain America franchise in matching T-shirts and baseball caps, replete with Evans's beaming face.

[4.5] Obviously, students don't always have direct access to such materials, so on my module they are given physical archives training (courtesy of our Special Collections staff), schooled in accessing various digital archives such as Lantern (https://lantern.mediahist.org/) and encouraged to access items in our host institution's own cinema archives, such as the Hammer Horror archive and the Indian Cinema archive (https://www.dmu.ac.uk/research/centres-institutes/cathi/partnerships-and-collaborations.aspx) or Special Collection's film star scrapbook collection, much of which is available digitally.

[4.6] But however students accessed materials, the levels of effort, self-aware irony, and fannish enthusiasm evident in the presentations around these materials bodes well for the learners moving beyond their familiar contextual frames and seeking to grasp those crucial subsequent stages of deeper critical engagement—the threshold concepts.

5. Subjectivity versus objectivity: "I think it's time to ask yourself, what do you believe in?"

[5.1] The most obvious pitfall of fandom as a pedagogical tool is both fandom's biggest benefit and its biggest drawback: its inherent subjectivity. As has already been discussed, fandom is about personal experience and taste. There is a prevailing assumption, which fan studies as a discipline has worked hard to counter, that fans lack adequate distance and are excessively emotional, incoherent, illogical—that fandom is unreliable (Ang 1989; Radway 1982; Jensen 1992).

[5.2] Film history aspires to objectivity but is, of course, not objective. Even the most empirical research is a product of choices and interpretations: decisions, norms, values, prejudgements, presuppositions, and maybe even prejudices are imposed upon artifacts. As Shanks and Hodder observe

[5.3] The expressive, aesthetic, and emotive qualities of archaeological projects have been largely downplayed or even denigrated over the past three decades as archaeologists have sought an objective scientific practice. In popular imagination the archaeological is far more than a neutral acquisition of knowledge; the material presence of the past is an emotive field of cultural interest and political dispute. The practice of archaeology is also an emotive, aesthetic, and expressive experience. This affective component of archaeological labour is social as well as personal, relating to the social experiences of archaeological practice, of belonging to the archaeological community and a discipline or academic discourse. Of course, such experiences are immediately political. (1995, 12)

[5.4] Archaeologists and historians are expected to maintain an objective distance. However, this attempted objective impartiality can mask taste judgements and—either inadvertently or deliberately—reinforce biases, hierarchies, and cultural inequalities, working in a hegemonic fashion to make these underlying disparities and divisions seem natural and inevitable. But as Hills (2002), McKee (2007), and Larsen and Zubernis (2012) have all considered, what is the difference between a film fan and a film scholar? Often very little. Does a fan seek to enjoy a text while a scholar seeks to understand it? Even these lines are blurred, particularly so when learners engage in affinity space learning premised on their own interests and expertise.

[5.5] This approach not only places fan learners in a much better position to trade up within the learning economy and realize their academic potential but also moves to address the need to give voice to the kind of marginalized perspectives discussed by scholars such as hooks (1994). And while there is a risk here that some learners might assume that their experience, the fandom that they choose to share with their colearners, or the ways in which they express their fandom are typical when they may in fact be exceptional, this is also the case for other autoethnographic approaches.

6. Interpretation and getting it right: "They're digging in the wrong place!"

[6.1] Excavating and assembling meaning is a complex, polysemic process. In any learning scenario, fan focused or not, learners can miss the point that the learning facilitator seeks to teach. Teaching through fandom initially appears to complicate matters further, as a key gratification and articulation of fandom is the desire to demonstrate to others one's accumulated knowledge around a favored topic. As such there is potential, due to personal investment, for the learner to offer a torrent of trivia rather than critical comment, forgetting that they should be considering the gaps between the texts: the theoretical, cultural, historical, and industrial frameworks as well as the texts themselves, the film, the star, and/or the director for which they have an affection.

[6.2] Yet this fannish desire to demonstrate one's expertise is not unlike the academic impulse. In both contexts, it is the type of knowledge that the learner demonstrates, the discrimination employed, and the resultant connections forged that matter. As meanings are negotiated, and theories and speculations are built out of this nexus of sources, the gaps between these texts are what provide the required space and opportunity for critical thought. As Booth (2018, 123) observes, affinity space learning, because of its collaborative, peer-to-peer approach, allows space for "safely controlled and monitored transgressions," providing an ideal opportunity for learners to sift trivia, include the necessary context, and suggest and consider a number of ideas and explanations regarding particular artifacts before settling upon the most likely interpretation. For example, in my workshops, learners work in small groups of a maximum of four. Where needed, I circulate around the learning environment, checking in to offer reassurance before learners feed their group observations back to the rest of the learners. This interpretation analogy is useful as it brings us back to the importance of linguistic scaffolding and a learner's contextual frame. As Shanks and Hodder observe: "To interpret something is to figure out what it means. A translator conveys the sense or meaning of something which is in a different language or medium. In this way interpretation is fundamentally about meaning. Note however that the translation is not a simple and mechanical act but involves careful judgement as to the appropriate shades of meaning, often taking account of context, idiom and gesture which can seriously affect the meaning of words taken on their own" (1995, 4–5).

[6.3] That said, meanings are obviously not entirely elastic. As Shanks and Hodder also observe: "To hold that archaeology is a mode of production of the past does not mean anything can be made. A potter cannot make anything out of clay. Clay has properties: weight, plasticity, viscosity, tensile strength after firing etc., which will not allow certain constructions. The technical skill of the potter involves working with these properties while designing and making so there is no idealism here which would have a count of the archaeologist inventing whatever past they might wish" (1995, 12). This opportunity for the learner to ascertain that meaning is "an ongoing process" and as such that "final and definitive interpretation is a closure which is to be avoided or suspected at the least" (4–5) is key and provides a useful answer to learner anxiety surrounding getting the right answer. There is no right answer, just the most likely answer, and this can be subject to change in light of new evidence.

7. Considering frames of reference: "'X' never, ever marks the spot."

[7.1] Given the importance of a learner's contextual frame, an issue also arises with learners potentially being unacquainted with a number of nuanced ideological implications that a text may offer, due to an unfamiliarity with that object's context. An example from my own recent learning experience is helpful here.

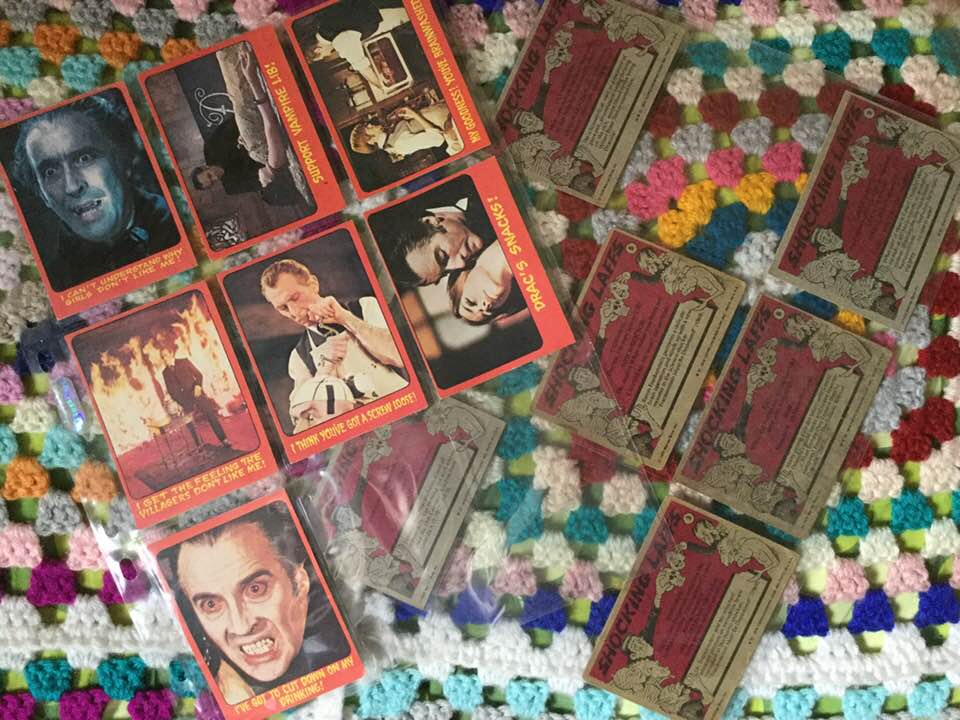

[7.2] Recently a fellow film historian kindly shared their Hammer Horror bubble gum cards with me (figure 2). They still smelled faintly of synthetic strawberry, some forty years later. They were 2×3″, so handy for pockets or, if you were more grown up, your first wallet. A glossy, gaudy, colored photograph and an awful punning caption featured on one side of the card; the other side had a matte finish and promised its collector "shocking laffs" using a deliberately anarchic, juvenile, and colloquial misspelling suggesting informality, naivety, or silliness as well as a subversion or rejection of correct English. This, combined with the accompanying cartoon depictions of cartoon monsters and ghouls rendered in an illustrative style reminiscent of then-contemporaneous British kid's comics Shiver and Shake and Monster Fun, gives the cards an anarchic, willfully camp feel. The use of the word "shocking" carries a dual implication here: the font suggests electrification or electrocution, in the manner of the Universal Studios' horror classic Frankenstein ('It's alive! Alive!'), while reference is also presumably being made to two awful jokes that appear on each card alongside a brief factual detail pertaining to the tantalizing photograph on the reverse and that are clearly to be understood as shockingly bad.

Figure 2. Hammer Horror bubble gum cards

[7.3] The cards were creased, bent, and faded in places. The owner asked me, "Why do you think the corners are so battered?" I replied, "where they've been pushed into pockets?" Having no personal experience of collecting such cards, I lacked the relevant contextual frame. While I was aware that swapping is common within collector culture, I was unaware that within this fan's particular working-class, northern British collecting culture, young collectors gambled with these cards. My historian friend explained that in his experience, a desired card would be placed on the ground a few feet away, and fellow collectors would then attempt to throw one of their own cards at the desired card. If their card landed touching any part of the desired card, the thrower would win said card. If it didn't touch, they not only didn't get the desired card, but they also had to surrender their thrown card. It was the repeated throwing that blunted the corners of these cards. Experiencing these artifacts out of context, how would I have known this? I needed that contextual frame.

[7.4] As a film historian, my own research interests lie in what the material culture surrounding film (particularly Hollywood film, between the 1910s and the 1960s) tells us about broader social contexts. I work with denigrated forms such as pinup photography, slash fiction, and pornography, as well as what Gray (2010) would term "media paratexts," such as press books, posters, film fan annuals, film star fan club publications, film star fiction, and film star and celebrity advertising endorsements (Wright 2013, 2015, 2016; Wright and Smith 2019). This approach, which maps onto Klinger's (1997) notion of a film's "discursive surround" (so not just production, distribution, and exhibition, but other related ancillary materials, such as the film's merchandising, reviews, and fan responses), enables me to more clearly understand a film in its entirety and how "such contextual elements…helped negotiate the film's social meanings and public reception" (114). Put another way, Glancy observes that "Magazines, along with critical reviews, fan clubs, promotional materials such as posters and postcards, and other forms of film ephemera, belong to what Kuhn (2002, 9) has termed 'a cinema culture thriving off the screen and outside the doors of the picture palace'." (2011, 455).

[7.5] Of course the "discursive surround" methodological approach to historical research isn't uncommon within film studies. The first recorded use of the term "new film history" was in 1985 by Thomas Elsaesser, who "noted the tendency of [then] recent scholarly works to move beyond film history as just the history of films and to consider how film style and aesthetics were influenced, even determined, by economic, industrial and technological factors" (quoted in Chapman, Glancy, and Harper 2007, 5). As Maltby (2011, 3) observes in his summary of the new film history field, before long, new film history became "[a significant] trend in cinema history research [which]…shifted its focus away from the content of films to consider their circulation and consumption and to examine the cinema as a site of social and cultural exchange."

[7.6] My methodological approach is one branch within this broader development. It was through engaging with the kind of primary resources previously mentioned and examining them within an interpretive archaeological framework, akin to that discussed by archaeologists Renfrew and Bahn as "the study of past ways of thought from material remains" (2000, 385), that my own learning really took off. Placed within a functional context, previously abstract film studies theories and contexts began to gain relevance or affinity to me as a learner.

[7.7] While sourcing and utilizing primary resources is common in postgraduate film history research, undergraduate learners tend to avoid this approach in assessments. They might insert box office figures from rottentomatoes.com into their arguments as a problematically simplistic shorthand to demonstrate the success or failure of a film, but their critical assessment of that material is generally limited. In my experience, learners tend to need frequent reassurance that, for example, analyzing a film's poster could offer just as fascinating an insight into a film's broader contexts as could a textual analysis of the film itself.

[7.8] This apprehension among learners regarding primary resources is surprising and suggests an unfamiliarity or uncertainty regarding this methodological approach rather than idleness, lack of originality, or lack of ability. In my experience, learners tend to be most enthusiastic and animated in learning sessions where they get to work with—and learn from—such resources.

8. The learner's tool kit and threshold concepts: "Choose wisely. The true Grail will bring life; the false Grail will take it from you."

[8.1] Teaching film history experientially can expand learners' frames of reference and the skills tool kit they use to demonstrate their aptitude for critical thinking. To master film history, a learner must develop and be able to demonstrate their ability to think critically and apply those critical observations in new contexts in order to identify the trends and anomalies that are the stuff of the history field. As such, critical thinking is what pedagogical theorists Meyer and Land (2006) call a "threshold concept," or one of the "conceptual building block[s] that progress the understanding of the subject." As with other threshold concepts, critical thinking is complex and challenging, and a learner will have to revisit what it means to think critically a number of times as part of a "recursive process" (Cousin 2006, 5) before they attain mastery of it.

[8.2] In his 2010 talk "Threshold Concepts and Issues of Interdisciplinarity," Land advocates for placing learners in learning contexts that they find strange in order to challenge and prepare them for the "super-complexities" of life beyond education. This approach seems logical and complements the safe yet challenging nature of the affinity space. It must be kept in mind, however, that there is potential—if the learning method is presented to the learner without adequate planning—to cause the learner undue anxiety, damage their confidence, and actually arrest their learning.

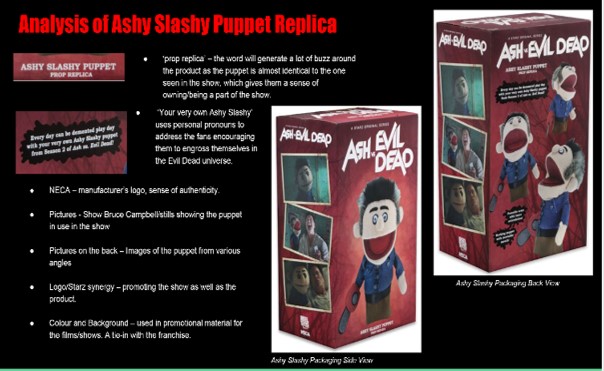

[8.3] Returning once more to my Indiana Jones analogy, I argue that learners should be urged to seek out material treasures for themselves and encouraged and enabled to explore around and beyond that artifact as a means of investigating broader contexts. These treasures provide the facilitator with an interactive means through which to introduce strange new theories or concepts to learners or to help to reinforce significant, foundational theories and concepts introduced on the program while providing the learner with a means to demonstrate their learning through the application of theory or idea to an appropriate external example. I have been talked through fan cultures around the cult actor Bruce Campbell (figure 3) and director Wes Anderson. I've been offered a feminist perspective on the marketing of Harley Quinn sex dolls and a Black British perspective on the representation of the cast of Marvel's Black Panther. I have even been talked through the politics of fan handicrafting through the use of a "Home is Where the Demogorgon Is" cross-stitch sampler, inspired by the Netflix franchise Stranger Things, in an approach evocative of Brigid Cherry's (2016) work Cult Media Fandom and Textiles. These presentations are often extremely engaging, competent, and, occasionally, deeply moving historical studies.

Figure 3. Slide from a student presentation

[8.4] As learners work in workshops and observe others' practices and presentations, their direct acquaintance with such objects, in Cousin's (2006) terms, increases their "experiential proximity" to different, unfamiliar resources, contexts, and ideas. They are investing in a resource and increasing their "emotional capital," a term that Lihong Wang (2015) notes was "coined by Cousin (2006) after Bourdieu's (1979) cultural capital to refer to the emotional positioning of students in terms of the receptivity to the learning of otherness. Thus, the students with greater experiential proximity to the aspects of otherness under examination may bring more emotional capital to their understanding of them" (93).

[8.5] As learning facilitators, we work to increase learners' emotional capital in the expectation that by directly engaging with such items, the learner stands a greater chance of comprehending the contexts that these items reveal. The learner is initially encouraged to consider the other or alien resource, making parallels with resources they have previously encountered. As their familiarity with the resource increases, they should be able to unlock the "inert knowledge" (Perkins 2006)—knowledge they already possess but may not yet be confident enough to utilize or may until this time, have not realized its relevance. In turn, their confidence should grow, and they should be more inclined to incorporate the new methodology and at least some of the resource's contextual details into their repertoire of acquired knowledge.

[8.6] As I have already suggested, learners' concerns around interpretation are not unfounded, but they are mistargeted. More often than not, concerns around critical thought are focused on getting the right answer rather than on the actual business of history—exploring the range of potential answers based on current available evidence. When I approach peer-to-peer working groups in workshops and ask the learners how they are doing, a common response is concern that they don't have a definitive answer or interpretation of a resource. In response I use the analogy of detective work or the archaeological dig, whereby numerous lines of enquiry should remain open. Furthermore, when discussion opens up to the larger group, the various interpretations offered demonstrate and reinforce the polysemic potential of resources.

[8.7] Archaeologists Renfrew and Bahn (2000) highlight how the arbitrary nature of symbols used to communicate within any material culture means that there is considerable potential for differences in interpretation, certainly when those representations are removed from their original contextual anchors, such as language or history. As Leslie Poles Hartley famously observed, "the past is a different country. They do things differently there"' (2004, 5). By implication then, when facilitating film history learning, it is likely that both foreign and domestic learners will perceive older historical resources as alien or strange. This is not a drawback. This strangeness places all learners at an even point of departure, provided all learners are given similar means to explore the resource and its context. Furthermore, a distance from the culture/era that produced these resources can offer a considerable advantage to learners seeking to develop their critical thinking skills. Just as Gramsci (1992, 100) theorized that the strength of hegemony—the dominant ideology—lies in its seeming naturalness, so the ideological messages that these resources convey may seem natural and thus imperceptible to those who are habituated in that culture.

[8.8] A useful example can be found in Renfrew and Bahn's discussion of a prehistoric Scandinavian rock carving, observing that it "appears to us to be a boat, we cannot without further research be certain that it is a boat. It might very well be a sledge in this cold region. But the people who made the carving would have had no difficulty interpreting its meaning. Similarly, people speaking different languages use different words to describe the same thing—one object or idea may be expressed symbolically in many different ways" (2000, 385–86). Again, context is vital and any contextual shift across culture or time period results in increased ambiguity, making it increasingly difficult to reliably and definitively determine a text's original ideological implications. Nevertheless, the otherness that historical artifacts such as the one described above represent and the inherent inability to definitively interpret or translate what they mean encourage us to be reflexive and curious: to speculate, hypothesize, and engage in critical thinking.

[8.9] This brings me to my final example. Due to the development in the late 1970s of stardom studies, where film stars and celebrities are examined from semiotic, sociological, and philosophical perspectives, current film studies learners may be aware of a coterie of classical-era Hollywood film stars such as Cary Grant and of a methodological technique used by scholars such as Dyer (1986) of watching one or more of such a star’s films to gain insights into the range of meanings they may have had or may now offer to contemporaneous and contemporary audiences, through their performance, appearance, and the ideology of their films.

[8.10] However, as Dyer (1986, 3) notes, stars are more than a signifying element within a film. Their stardom is comprised of a "total star text" whereby they are made available across a range of media, and like any other signifier, their meaning may also alter across time and culture. It is this range of representations that cumulatively forms a broader star image: "With stars the 'terms' involved are essentially images. By 'image' here I do not understand an exclusively visual sign, but rather a complex configuration of visual, verbal and aural signs. This configuration may constitute the general image of stardom or of a particular star. It is manifest not only in films but in all kinds of media text" (Dyer 1998, 34).

[8.11] Looking beyond Grant's films to consider the contemporaneous culture of the period in which he appeared in films (1930s–1960s) can offer learners useful insights into his audience appeal, what his star persona was, and how those understandings might have shifted over time in light of new evidence. Well-chosen artifacts can also offer a valuable opportunity for learners to engage with broader ideas that Grant's stardom may have touched upon or that it touches upon now that may not be evident from his films alone. In previous workshops, I have demonstrated how Grant was repeatedly cast as a debonair leading man and onscreen romantic interest to the most glamorous female stars in American cinema but how artifacts from the 1930s, such as Edith Gwynn's "Hollywood Party Line" gossip column in American film fan magazine Photoplay alluded to Grant's possible homosexuality. Objects such as these function like a breach in the façade of Hollywood stardom, providing the historian with an illicit glimpse into the workings of Hollywood's star machine, offering a counter to Grant's sophisticated heterosexual persona and suggesting an actor forced to disguise his authentic self and sexuality to succeed within a conservative industry and culture.

[8.12] One can see, then, that resources such as these can be useful tools to prompt debate around a raft of complex issues with continued relevance for today's learners, such as the representation of masculinity, the politics of sexual identity, the problems with stardom, and the incongruous relationship between celebrity and authenticity. Far beyond learning just about a star or about a clutch of artifacts linked to a specific star, learners are being prepared for the kind of super-complexities that Land (2010) refers to as existing in the real world, beyond education.

9. Conclusion

[9.1] So how do we engage students in a subject such as film history, a subject that learners can perceive to be irrelevant and dull and yet is necessarily central to their film studies program?

[9.2] Altering the learner/facilitator power balance through affinity space learning and increasing emotional capital provides a key route to engagement, understanding, and enlightenment, using the fact that all learners are able to identify themselves as fans of something as a starting point. As many pedagogy scholars have demonstrated, engaging learners via experiential means is an effective way of provoking learner engagement, as the learner's own personal fan experience (their contextual frame) can be used to engage them.

[9.3] Through direct contact with primary resources, learners are less likely to exhibit the signs of what Biggs and Tang (2011) term as "surface" learning, whereby they utilize only "low cognitive level abilities" (24), and are instead more likely to actively engage, exhibiting signs of "deep" learning, whereby the learner grasps the politics and the value of studying history and considers the resources "appropriately and meaningfully," hopefully retaining what they have learned (26).

[9.4] The kind of artifacts I advocate the use of may initially appear to be other to learners because of their age, obsolescence, condition, or the specificity of the fandom and or contexts they refer to. Culturally and within teaching, there is an understandable drift away from physical media toward the digital, so you might think that an in-the-flesh encounter with an artifact could seem dated to learners, but anonymous feedback on the module I deliver consistently highlights the pleasures garnered from these physical interventions with film and film fan history, with learners commenting upon their surprise at how relevant/useful the module was and how they enjoyed sharing their fandom with others and giving it serious attention. Assessment results on my module also suggest that by actually handling these objects within the context of a suitably supportive yet challenging environment for learner-led debate and exploration, those learners incrementally developed confidence, critical thinking skills, and familiarity with the research method. This also enabled them to translate unfamiliarity into mastery and apply their own contextual frame to another, in a manner that one learner observed "felt like cheating" because it was "fun and easy to grasp."

[9.5] As Hills observes, fan cultures function as "interpretive communities" that "display self-reflexivity" (2002, 182) so it's no wonder then that "some teachers…hope to leverage their participatory and transformative potential in order to encourage the critical faculties of students" (Pande 2018, 96) just as many transformative fan works "frequently play in the gaps and margins of their source material" (Scott 2019, 126). Learners using this approach are asked to do the same: to work reflexively and playfully and to examine potential, a process the student cited above clearly enjoyed.

[9.6] An object-focused approach to history or to any other social science is productive because it starts with the learners. Its foundation is learner identification. Working from the learner's contextual frame outward, it is based on personal engagement, piquing each learner's interests, whatever their contextual frame, to increase interest and confidence levels, which can then be exploited to demonstrate and reinforce threshold, critical, and research skills. The use of material culture itself—the opportunity for learners to handle history and experience the tactile pleasures offered by direct contact with and investigation of fan artifacts—reinforces that sense of investment and affinity, gradually and safely extending their contextual frame to make the strange familiar and handing agency to learners.

[9.7] For that reason—if I may crowbar in two final Indy quotes—it may seem that in using fandom as pedagogy, "you are meddling with powers you can't possibly comprehend," but the rewards, not only for learners but also for learning facilitators, are so very worth it. "Trust me."

10. Five tips for fandom as a teaching tool

[10.1] Open your first workshop by discussing your learners' experiences of fandom. Lead that discussion with an example of your own fandom before moving to the first student. This year I confessed my love of Ru Paul's Drag Race. As a result, a coterie of learners would approach me at the end of each workshop to discuss the latest developments in the current season. At the end of the term, two of that group delivered a superb presentation on queer baiting in popular culture.

[10.2] It is fine to refer to your own fandom throughout your module. In fact, it helps. It levels the playing field.

[10.3] Bring plenty of physical examples to workshops. Variety is key. You want to tickle as many fandom fancies as possible. Sometimes the most unlikely artifact prompts the most animated discussion.

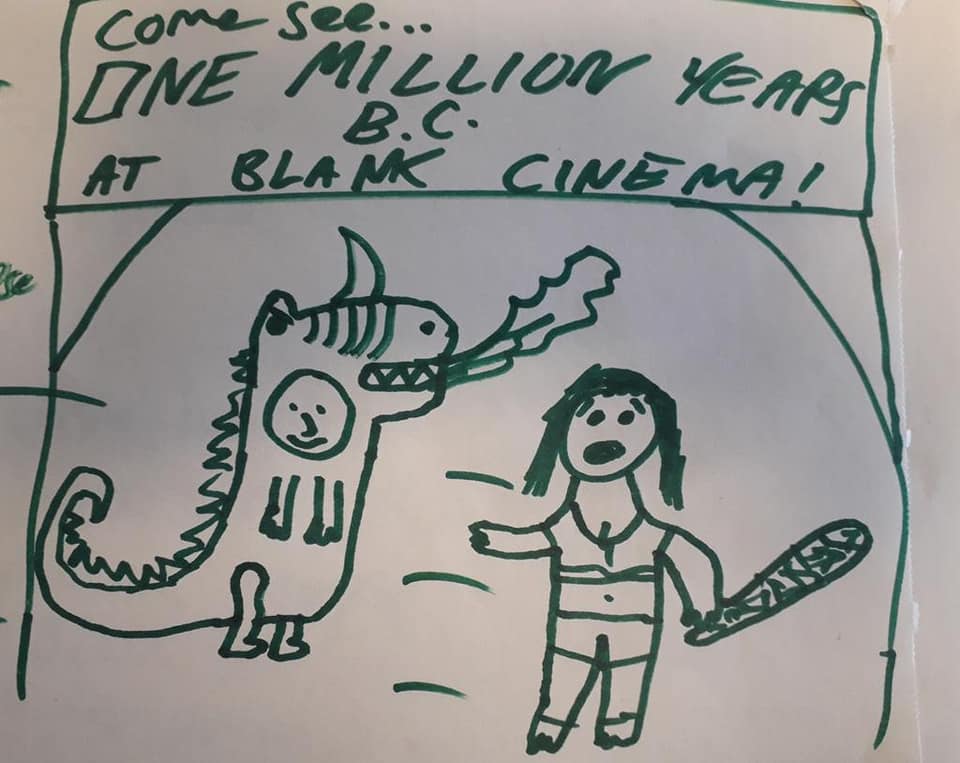

[10.4] Allow learners to respond to resources in a range of ways. Always have paper and pens on hand for learners to work with. Bullet points and spider diagrams are the standard learner presentation style, but last year I had two students who each week would produce a series of detailed, wryly observed cartoons to answer the tasks I had set them. A close discussion of them became a staple of each week's larger group discussions (figure 4).

Figure 4. A learner's interpretation of how cinema exhibitors may have generated ballyhoo outside their theaters around One Million Years BC (1966).

[10.5] Seek consent to share all written/drawn responses with your learners after the session. It is not high tech, but I currently photograph the group work that learners produce and upload the photos onto the virtual learning environment for them to refer back to.

11. Acknowledgments

[11.1] Thanks to Heidi Waddington and to Heather Savigny, Daisy Richards, Claire Sedgewick, Justin Smith, and Phyll Smith, all of whom are excellent educators and who kindly gave feedback, support, and advice.