1. Introduction

[1.1] In her book Theatre Audiences (1997), Susan Bennett discusses the emergence of new theatre groups who give voice to marginalized audiences and notes that this proliferation "demands new definitions of theatre and recognition of new non-traditional audiences" (1). A burgeoning phenomenon targeting an enthusiastically participatory audience not often associated with live theatre has been growing out of small, unconventional, often unconnected theatrical companies in a number of cities that cultivate marginal and quirky theatre communities. The most prominent of these companies, Vampire Cowboys, calls this phenomenon "geek theatre" (Bray 2014, 125).

[1.2] I discuss the ways in which geek theatre actively accomplishes what Bennet calls "democratization" of theatre by engaging the already participatory geek/fandom audience (Bennett 1997). Speaking as a geek and using Dad's Garage Theatre Company's productions of Jon Carr's Black Nerd (2018) and Travis Sharp and Haddon Kime's Wicket: A Parody Musical (2017a) as case studies, I first examine how geek theatre actively embodies geek fan culture's concern, as identified by fandom scholars, with creative ownership of stories and characters, including how fan writers choose to disrupt dominant narratives established by producers. In this way, geek theatre strives toward democratization of content. Second, I illustrate how geek theatre strives toward democratization in representation via its casting practices and exploration of overlooked racial and gendered perspectives. I argue that geek plays achieve these purposes by using (1) metatheatrical self-awareness as a method of critiquing and reframing narrative, and (2) geek fan culture's resistant reading techniques that find and exploit gaps in its source materials for expressing marginalized voices.

[1.3] The Janissary Collective, an interdepartmental operation consisting of students and faculty that functions as a forum for discourse out of the telecommunications department at Indiana University, has commented that "one of the documented hallmarks of fan communities is an immensely prolific, widespread set of discursive practices that involves the creation, critique and circulation of fan meaning and metatext" (2014). Likewise, geek theatre does not merely regurgitate content or fantasize within the comfort of precreated plotlines. Participatory geek fan culture has created social and creative means of actively critiquing the limitations of its consumed media and then reshaping it to better represent the marginalized desires to which it so often appeals. Wicket, implementing layers of dialogic metatheatricality and concepts exemplary of fandom practices as identified by fan studies scholars, discursively engages with issues of communal versus capitalistic creative ownership, propaganda, and dictatorship, vocal suppression of minorities, and hegemonic narrative control. Black Nerd engages in this discourse on two levels, critiquing source texts and fan culture's tendencies to interpret these texts in a manner that generally ignores issues of race and minority cultural realities.

2. Live nerdity on stage

[2.1] Here, I define geek theatre by two criteria: (1) the subject matter must be dealing with a "geeky" fandom, such as sci-fi, fantasy, comics, gaming, and anime; (2) the play must specifically target a geek/fan audience, as opposed to adapting the subject matter to appeal to a broader mainstream audience—"by geeks, for geeks."

[2.2] John Patrick Bray (2014) has established how geek theatre, which targets fan audiences, should be distinguished from the current trend of "geek chic" that has popularized aspects of fandoms via works such as Broadway's Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark (2010). The latter adapts "geeky" source material with the specific aim of making it palatable to mass mainstream culture, often with no interest in catering to or even considering long-time fans of that source material. Basically, it might be socially acceptable nowadays to go see a Marvel or Star Wars movie, but collecting comics or cosplaying at a Star Wars convention are still behaviors often considered worthy of ostracization.

[2.3] There remains a wide gap between the geek chic audience and the geek fan audience. Bray notes that geek theatre companies such as Vampire Cowboys have earned their success "by actively cultivating not just an audience or a subscriber base, but a fandom" (2014, 121). Nongeek audience members are not necessarily excluded from engaging with geek theatre, as the playwrights typically strive toward some degree of accessibility to all; however, the manner in which these plays engage with their audience assumes a certain investment in geek fan culture. In fact, geek theatre feeds into the participatory nature of this culture, which includes interactive creative practices such as cosplay and the sharing of transformative fan-made media such as art, videos, fan fiction, and filk (fan songs). These plays are, in fact, already in conversation with their audiences before the show even begins, engaging directly with the ongoing discourse of geek fan culture.

[2.4] Despite an overlap in subject matter, geek theatre should be differentiated from the genres of science fiction and fantasy theatre. Although geek theatre may be written in the genres of sci-fi and fantasy, these genres are not always written with geek audiences in mind; they are more often used as metaphors for discussing contemporary social issues, usually targeting as broad an audience as possible. Fantasy has arguably been a part of theatre throughout its entire history and across cultures, given theatre's roots in mythology. Classical Greek plays are filled with magic elements and fantastical creatures. Certainly high fantasy of the past century—including, most obviously, Lord of the Rings and its various adaptations—has drawn heavily, both in content and inspiration, upon epic mythological sagas such as Wagner's Ring Cycle. Similarly, science fiction theatre such as Karel Čapek's R. U. R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) (1923) has strongly influenced the development of the science fiction genre.

[2.5] Media fandom—and by extension much of geek culture today—branched off from the culture of science fiction literary conferences in the 1960s with the advent of Star Trek (NBC, 1966–1969). Specifically, I am referring to the transformative impulses of fandom, with which geek plays such as Wicket and Black Nerd engage. As documented by Camille Bacon-Smith in her foundational work in fan studies Enterprising Women (1992) and Henry Jenkins in Textual Poachers (1992), this predominantly female fan base, with its many prolific producers of fan fiction zines and other transformative fan-made media, became the driving force behind the earliest media fandom conventions, developing the social structure upon which geek fan culture continues to function over its rapidly expanding forums and communities. Francesca Coppa's "A Brief History of Media Fandom" (2006) offers a more thorough overview of the emergence of media fandom out of earlier science fiction fandom.

[2.6] Yet while geek theatre owes some of its theatrical roots to science fiction and fantasy theatre—and certainly overlaps with these genres in content—it shares more in common, in its style and target audience, with the tradition of burlesque as, in the words of Frances Teague, "comedy of imitation" (2006, 83). Geek theatre tends toward the burlesque both in its reliance on audience familiarity with parodied source material and in its blend of irreverent critique with reverent celebration of that same source material. It hinges upon its fan-based audiences' nostalgia and enthusiasm for the material it references, often in the form of camp and parody, and their ability to get the joke. Yet as Lawrence Levine points out about burlesque, it is meant not only to entertain but can also carry a serious message, even serve as a corrective for the source text (1984, 35) (note 1). On a deeper level, it offers a divergent and resistant reading to the source text. In this way, geek theatre follows in the transformative model of fan behavior, which readapts the raw materials of established characters and settings to explore perspectives and desires of marginalized groups who do not often find adequate representation in content producers' official texts, as opposed to the model of affirmational fandom, which strictly explores these fictional universes without contradicting or transgressing the official canon.

[2.7] Often affirmational fandom is associated with male fan practices and considered sanctioned by media producers, whereas transformative fandom is associated with female fan practices and considered unsanctioned and transgressive (obsession_inc 2009). Fan scholars Suzanne Scott (2019) and Melanie E. S. Kohnen (2018) have both delved into this gendered hierarchy within mainstream portrayals of types of fan behaviors (note 2). Scott also points out that the term "transformative" has been adopted to combat the label of "derivative" to describe fans' creative adaptations (2019, 38). Geek fan culture, like Susan Bennett's "emancipated spectator" (1997), blurs the line between consumer and producer, between audience and actor. Francesca Coppa likens fan fiction to theatrical performance, in that a live audience is a necessity (2014, 232). Fan culture requires fan texts, and these texts require an audience in order to proliferate. This interaction of text and audience is the foundation of fandom's social structure. Within this culture, play and production frequently overlap to create a reciprocal cycle of audience-author exchange, in which the audience members constantly author new material for each other, giving rise to an ever-expanding library of alternate tellings and retellings, recasting, and reenvisioning that plumb the depths of story and fashion it to fit the needs of each audience/author. In this manner, the productivity of geek fandoms is self-sustaining and potentially limitless, recaptivating its audience over and over in addition to constantly making space for more.

[2.8] Like the fan fiction writers who founded media fan culture, writers of geek theatre are notable for queering and diversifying the stories and genres they adapt. The two best known forms of fan fiction are slash—same-sex romance or erotica, often based on a noncanonical pairing—and the Mary-Sue—a fantasized self-insert, usually in the form of a strong female lead. These common incarnations of fan writing are also the most notorious, distinctly setting their authors and content apart from the predominantly heterosexual, White, male producers of and cast of characters in traditional sci-fi and fantasy literature (Jenkins 1992)—and theatre. Geek theatre follows in this tradition of foregrounding divergent and outsider perspectives, often along the lines of gender and sexual orientation but also, to a lesser degree, in terms of racial critique.

[2.9] The celebrated geek theatre troupe Vampire Cowboys, for example, consciously strives toward a more diverse theatre. Playwright Qui Nguyen has called positive representation of queer, female, and ethnic minority characters Vampire Cowboys' "unwritten mission," and his plays have been nominated for GLAAD awards twice, in 2009 for Soul Samurai and 2012 for She Kills Monsters (Tseng 2010). Where sci-fi and fantasy theatre have typically marketed themselves as allegorical dramas high in spectacle to a broad universal audience, geek theatre has twisted allegory into parody specifically to criticize the assumptions of what the hegemonic mainstream calls "universal" and has chosen to target the geek, the queer, and the invisible minorities who excel at finding the gaps in the narrative where their own stories might find a foothold.

3. Dad's Garage presents the dork side

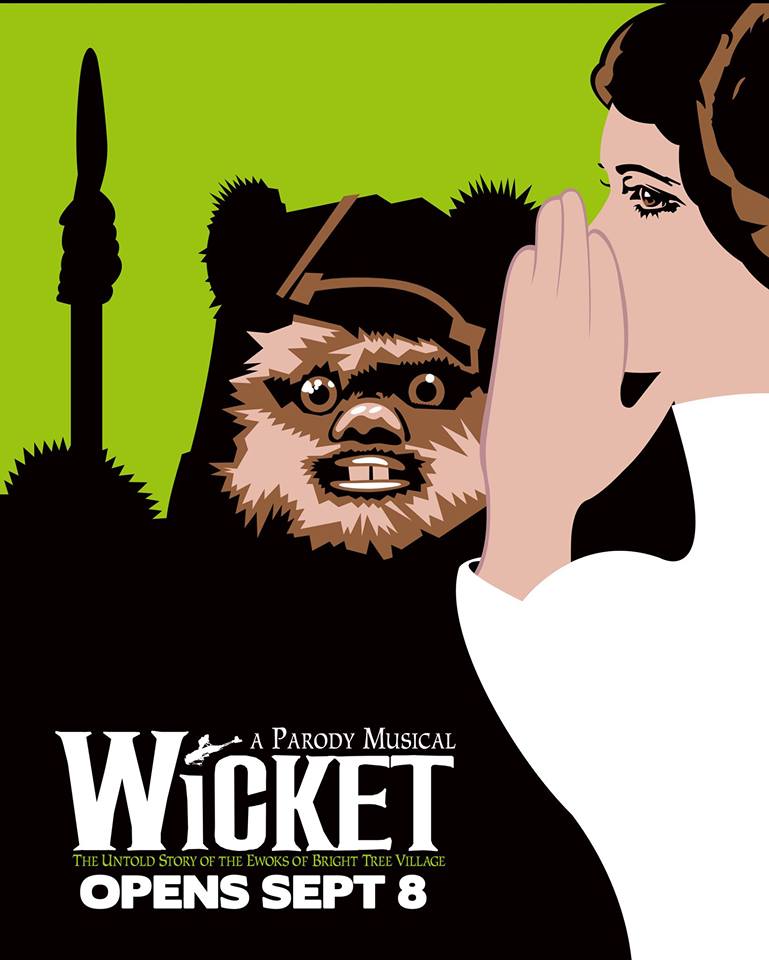

[3.1] Dad's Garage Theatre Company in Atlanta is an improvisational theatre whose ensemble members, all trained in-house, democratically select its major productions. The company has previously produced a multitude of geek theatre plays such as Wrath of Con (2012) by Jon Carr, Karon the Barbarian (2017) by Karen Cassady, and annual runs of Improvised Dungeons & Dragons, originally created by Mark Meer. In September 2017, Dad's Garage premiered Wicket: A Parody Musical by playwright Travis Sharp and composer Haddon Kime (figure 1). Wicket proved one of the best-selling shows in Dad's Garage history, pioneering a musical style that the writers have coined "wok rock," a synthesis of hip-hop with Ewok music from the Star Wars films (Sharp and Alilaw 2017). The show was nominated for seven 2017 BroadwayWorld Atlanta Awards and won Best New Work. Dad's Garage describes the show on its website as a story repurposed (much like the former church building that now houses the theatre):

[3.2] Wicket takes the classic Star Wars tale, and retells it from the Ewoks' perspective. Taking the concept of a revisionist history of a classic tale (similar to Wicked telling another side of the story of The Wizard of Oz), Wicket provides a completely new interpretation of what was going on in Star Wars.

Figure 1. Poster art for Wicket: A Parody Musical at Dad's Garage Theatre Company.

[3.3] More than a fun celebration of Star Wars, Wicket serves as a subversive commentary on top-down narrative control in today's culture. As Wicked does with the story of The Wizard of Oz, the parody musical Wicket retrospectively recounts the Battle of Endor from a radically different point of view than the film Return of the Jedi (1983). At the start of the story, the tribe of Ewoks have no idea that Emperor Palpatine has genetically engineered them all to enslave and sell as adorable toys. They have even been betrayed by one of their own, Logray, who has apprenticed himself to the Sith Master. Despite all the rules that say "size matters," the "pint-sized" Ewok Wicket believes he can be a hero—and get the girl, Kneesaa—if only he were given the chance. Meanwhile, the only Imperial to foresee the Ewok/Rebel uprising is a single mysterious Ensign—the Empire's first black female officer—whose evil-genius brilliance is repeatedly ignored by her superiors, to their detriment. The plot of the musical parody revolves around the three neglected narratives of Wicket, Princess Leia, and the Ensign.

[3.4] In spite of its success, Atlanta's media publications that regularly cover Dad's Garage productions—such as Creative Loafing, the Atlanta Journal/Constitution, and ArtsATL—did not cover Wicket. As writer Travis Sharp commented via personal correspondence, this oversight suggests that geek theatre "might not be taken seriously by the industry" in spite of its ability to attract "a passionate audience" who otherwise might not attend theatre.

[3.5] The world premiere of Jon Carr's semiautobiographical Black Nerd at Dad's Garage in July 2018, which by comparison began its run with relatively low ticket presales, quickly transformed into yet another sold-out hit as word of mouth spread through the local community. It attracted audiences not solely through the power of fandom but through its clear and compelling articulation of the complexities of racial identity and its relationship to expressing oneself against the grain of cultural expectations. Though loaded with satirical critique of pop culture texts, Black Nerd is not a parody in the vein of Wicket; rather, it is the intersectional story of a Black man navigating Black and fandom cultures, respectively. The Dad's Garage website description for Black Nerd begins simply with a question: "What happens when a black kid prefers listening to Weird Al over Kendrick Lamar, attend [sic] Dragon Con over the Jay-Z Concert, or Star Wars over Tyler Perry (there is still some debate about the prequels)?" On his own experiences growing up as a Black nerd, playwright Jon Carr states,

[3.6] I was always the weird kid [in my family] that 'talked too white.' But then going to DragonCon with all my nerdy friends, I was always the black kid…I would never quite fit in in whatever group of people that I was spending time with. (Carr 2017)

[3.7] As a Black male with a geeky streak, Carr describes his story as "a Black experience within the Black experience" (Carr 2017). His play uses self-referential metatheatricality, which constantly reminds the audience of the constructed nature of the script and performance, to examine both how mainstream culture dismisses geeks/nerds and how mainstream narratives—and by extension fandoms surrounding those narrative texts—overlook issues of race.

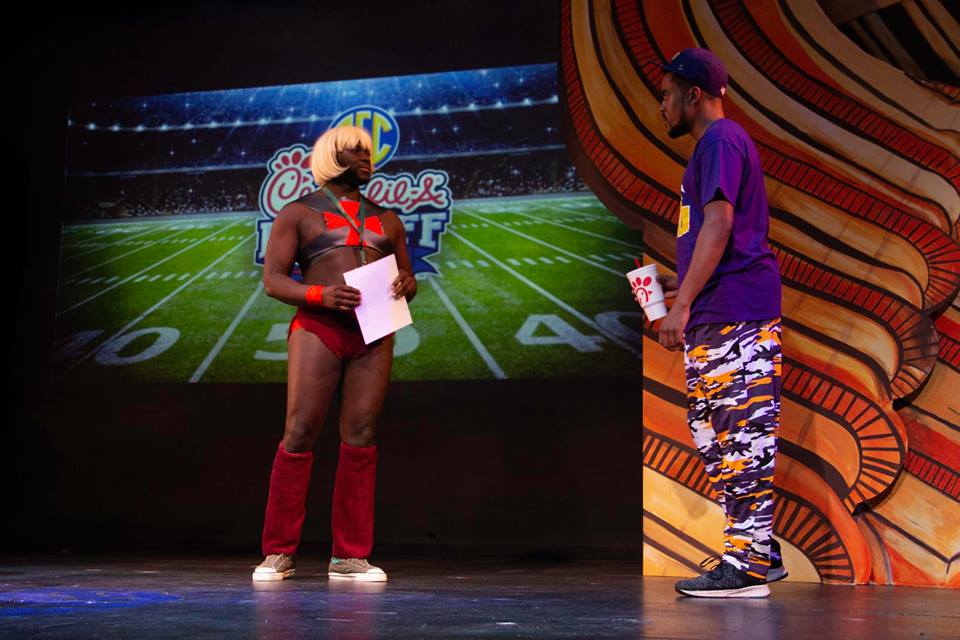

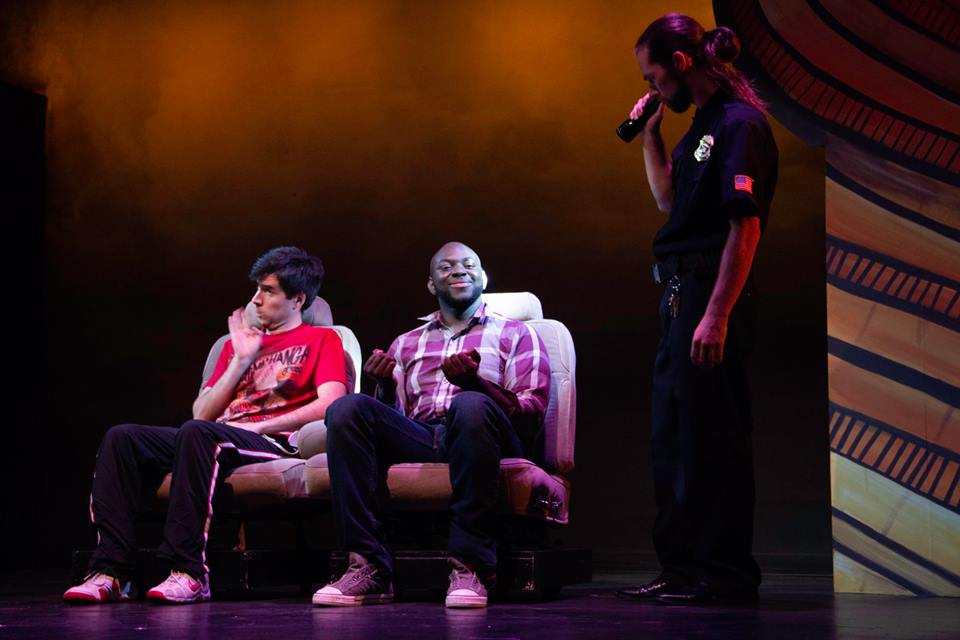

[3.8] Black Nerd's protagonist, Marcus, struggles to square his geek identity with pressures to fit the cultural image of Black masculinity that constantly bombard him from his Black family, from his White geeky friends, and from everyday run-ins with the realities of racial stereotyping (figures 2 and 3). The plot follows his preparation for and attendance at Dragon Con, a sci-fi/fantasy convention held annually in Atlanta and attended by tens of thousands of people, many of whom—like Marcus—cosplay as favorite characters from a wide range of fandoms (note 3). The play's scenes can be divided into three basic categories: (1) a running commentary on how race changes the narrative of conventional storytelling, particularly in popular film; (2) Marcus's attempts to navigate his relationship with family members who don't consider him "Black enough"; and (3) Marcus's attempts to navigate geek fan culture, in which he's generally treated as the token Black friend. With guidance from his unconventional, pot-smoking Grandma (figure 4), he balances the need to honestly express his own intersectional identity with these conflicting external expectations.

Figure 2. Marcus (Avery Sharpe), cosplaying He-Man, encounters LSU Football Fan (Freddy Boyd) in Black Nerd at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

Figure 3. Marcus (Avery Sharpe) and his friend Cosmo (Jon Wierenga) in a racially charged illegal traffic stop with a White cop (Cole Wadsworth) in Black Nerd at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

Figure 4. Grandma (Andrene Ward-Hammond) in Black Nerd at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

4. Speaking Geek

[4.1] A potential roadblock that every production of geek theatre must navigate is accessibility to nongeek audience members. Black Nerd, which opens with a scene at Marcus's family reunion, immediately underscores the difficulty geeks sometimes experience in relating to and communicating with nongeeks, or mundanes. This difficulty frequently goes both ways; while mundanes tend to misunderstand the motivations and interests of their geeky loved ones, likewise geeks struggle to understand the appeal of more mainstream interests and to live up to family and friends' expectations regarding normal modes of behavior. At first, Marcus is not obviously singled out as the main character—until he directly addresses the audience and claims the story as his own. He even suggests his cousin Cheeto as a more relatable candidate for a play's protagonist: "[Cheeto's] a colorful, complex and interesting character with an engaging back story. Unfortunately for you…I'm the protagonist. So no refunds" (Carr 2018, 10).

[4.2] The opening scene of Wicket—presenting Wicket Wystri Warrick the First, "hero of the rebellion, chieftain, star of two direct-to-video feature films," as a celebrity performing a solo, stand-up, autobiographical swan song (figure 5)—also directly embraces this issue when Wicket addresses "his" audience: "All humanoids?! Shiiiiit" (Sharp and Kime 2017a) (note 4). Just as Wicket, in context, must navigate the limited perspective and understanding of his human audience, who may or may not understand his cultural experiences as a minority species, geek theatre constantly walks a tightrope between in-group appeal to its target fan-based audience and accessibility to a broader mainstream audience.

Figure 5. Wicket (Karen Cassady) addresses his audience in Wicket at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[4.3] Wicket and Black Nerd actively enter a coded dialogue with the geeks among their audience members, and this shared language of obscure references vocalizes much more than simply inside jokes. In a prime example of geek-specific messaging in Wicket, audiences repeatedly went wild night after night when a punk-rock Princess "Sleia" (figure 6) shouted at the end of a long riff:

[4.4] Frag Jabba's chins!

Frag carbonite!

And FUCK MIDI-CHLORIANS! (Sharp and Kime 2017b)

Figure 6. Princess Leia (Eliana Marianes) raises a fist in protest in Wicket at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[4.5] The catharsis of this brief moment exemplifies the phenomenon Henry Jenkins has frequently identified as "the strange mixture of fascination and frustration" inherent in dedicated fandom (2006b, 55). Possibly the only aspect of Star Wars Episodes I–III as widely and as deeply hated as Jar Jar Binks is the concept of midi-chlorians: the biological explanation of Force sensitivity as a symbiotic relationship with microscopic organisms that live in the blood of sentient beings, which for many effectively destroyed the "magic" of the Force. The statement "fuck midichlorians" manages, in one phrase, to boil down acute fan sensitivity to the misuse and abuse of a beloved story and its characters by capitalistic producers—the perceived hijacking of the narrative by its own creators. In turn, geek theatre, like many fans and works of geek art, responds by hijacking it right back.

[4.6] Notably, the punk style—a term now culturally linked to an aesthetic in music, appearance, and attitude—developed in reaction to the term's use to devalue groups and individuals considered to be inferior or worthless. Stephen Colegrave and Chris Sullivan argue that "punk was always more than a T-shirt or a piece of loud music: it was an irrepressible attitude" that "rescued the word from its time-honoured place of shame and…dared to rock the status quo beyond the imagination of any previous generation" (2001, 12). By transferring this attitude to Princess Leia, to express both her own frustration as a character and fans' frustrations, the song pulls double duty, both appealing to punk music fans in the audience and making a statement regarding the reappropriation of derogatory labels. Additionally, Steve Waksman credits bands such as a Slayer—Princess Sleia's punned namesake—with an energizing "cross-fertilization" of musical styles such as metal and punk in defiance of notions of "musical purity," a statement that resonates with the remix culture of fandom (2009, 15).

[4.7] Aya Esther Hiyashi (2018) points out in her dissertation that music, including but not limited to the tradition of filk, is one of fandom's "most consistent features" (1): "No matter the contradictions and tensions within fandom…it is in musical performance that those things seemingly disappear. The ideals of fandom are what draw so many people to participate, and it is often through musical performance that these ideals are transformed into lived experience" (141). Wicket taps into this affect not only as a musical, but also by appealing to music fandoms as well as geeks in its stylistic choices. In his own engagement with music in Black Nerd, Marcus exemplifies the geek-pride attitude of unapologetic enthusiasm in a montage of his Dragon Con weekend activities, during which he inspirationally sings Journey's "Don't Stop Believin'" in Klingon, yet another instance of staking a claim in and mashing up celebrated pop culture content.

5. Defying Palpatine

[5.1] Narrative control is among the greatest concerns of fandom and has garnered much attention in fan studies, particularly the subject of fan–producer tensions. Legally, of course, producers, as owners of the source texts' copyrights, hold official power over canon, characters, and narrative. Fans, however, emphatically express their own claims to the fandoms in which they invest themselves. Wicket expresses this fan perspective directly:

[5.2] THE ENSIGN: When you release something you made into the universe, it's not yours anymore. It takes on a life of its own. It creates bonds, makes new connections. It would be hubris to believe that, just because you made it, it's yours to control forever.

EMPEROR PALPATINE: Look at who you are speaking to. Do you have any idea what I have accomplished? I have crushed rebellions…uprisings…small theatre companies! (Sharp and Kime 2017b)

[5.3] Without a shred of subtlety, the parody reshapes the character of Emperor Palpatine, the tyrannical dictator of the Galactic Empire, into a caricature of George Lucas.

[5.4] The fraught relationship between Lucas and his fans is long and complex. The charges against him are not only numerous but varied. His branding of Star Wars and other franchises as the foundation of a capitalist empire is legendary. In her book and solo stand-up Wishful Drinking (2008), Carrie Fisher joked, "Among George's many possessions, he owns my likeness, so that every time I look in the mirror I have to send him a couple of bucks!" (87). Wicket exploits this aspect of Lucas's character in its depiction of Palpatine's evil master plan: genetically engineering Ewoks "to sell as kids' playthings" (Sharp and Kime 2017b). Geeks, however, actively revel in the world of collectibles, so in many ways, shamelessly capitalistic or not, the plethora of Star Wars merchandise directly serves the interests of the fandom. As a Star Wars geek myself, I personally own more than one teddy-Ewok. Much more sinister, in the eyes of the fandom, are Lucas's perceived crimes against the fictional universe itself as well as its inhabitants.

[5.5] As Henry Jenkins has argued, although geek fan culture is bound to a basic loyalty to the content of the source texts, fans who invest themselves in these texts insist on the right to "evaluate the legitimacy" of new texts that enter into the canon, whether by fans or official series producers (2006b, 55). In the case of Star Wars, the classic trilogy has retained the staunch loyalty of its fan base. Much of Lucas's later work, including the special editions and the prequel trilogy, has been deemed catastrophically illegitimate by many fans. For instance, the Han-shot-first debacle has become a pop-culture controversy of mythic proportions (note 5). In short, Lucas's decision to pursue his own vision rather than the will of the fans proved his greatest transgression against the collective fandom.

[5.6] Even at its most critical, though, the fandom continues to desire an ongoing dialogic creation of its universe, wishing for and offering open collaboration upon the fandom universe: "It's ours…so we should share it. / If your prequel really sucks, we'll try and repair it" (Sharp and Kime 2017b). The wish for communal ownership and open collaboration arguably constitutes the heart of geek fan culture and certainly rests at the core of Wicket.

[5.7] The theatrical locale of this dialogic work is no accident nor of small significance. Francesca Coppa compares the philosophy underpinning all fan art to theatrical performativity in that "the script isn't the final product in theatre; in fact, one of the questions that theatre theorists have had to debate is the location of the work of art. Is it in the author's original script? Probably not" (2014, 230). In fan culture, no script can contain the possibilities of any given story, character, or universe. Rather than attempting to tighten the stranglehold of control, like real-life Grand Moff Tarkins (note 6), Jenkins suggests that media producers engage in a "moral economy" that balances the needs of the fans with those of the creators (2006b), a concept that opens up the landscape for transformative, dialogic work. Leia articulates the bottom line of the show while managing to boil down the concept of moral economy:

[5.8] LEIA: Well, you can make something great then realize it's not just yours anymore.

WICKET: Oh, so we make something great, and then we let everybody else do whatever they want with it.

LEIA: No. Just don't be a dick about it! (Sharp and Kime 2017a)

[5.9] The real villain in the story is the tyranny of the privileged "official" narrative and intolerance of deviant interpretations. This tyranny manifests its power in many forms, including monopoly of not only intellectual property, but also news media and even everyday social interactions. "The story has been carefully controlled by a dictator," confides Wicket to the audience at the show's outset (Sharp and Kime 2017a). As a parody, Wicket consciously avoids legal copyright violation—and reminds its audience of this fact. Yet simultaneously the show's plot overtly challenges the authority of the "dictator" in question—or rather, all who seek to limit public access to the narrative, in any form. Although George Lucas himself has been openly friendly toward and encouraging of fan work, his attitude is rare (note 7). Conversely, the franchise's current owner, Disney, historically has been notoriously hostile to infringements upon its copyrights (note 8). George Palpatine as the dictator does not neatly fit within the boundaries of his metaphor; the issue of creative control he is meant to embody is too big for his nonexistent britches (figure 7).

Figure 7. Emperor George Palpatine (Googie Unterhardt) in Wicket at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[5.10] The hegemony Wicket openly protests is not only creative, however. The Rules that govern the Ewok tribe—secretly designed to ensure their eventual submission as a species—insist on a cultural hierarchy that sounds suspiciously similar to phallocracy, the crux of the system being "size matters." Produced at a time when fake news is being shouted into the face of even the slightest resistance, when debate has utterly given way to slander, when diplomacy has been replaced by Twitter, one may experience understandable difficulty not hearing the voice of President Donald Trump in the lyrical taunt by Logray, as a "bigger" Ewok, to Wicket (figure 8), as his perceived social inferior:

[5.11] Look at you, look at me.

Little dude, what you see?

Whoopee wee, poopy poo—

Look at me, look at you. (Sharp and Kime 2017b)

Figure 8. Wicket (Karen Cassady) and his larger rival Logray (Rickey Boynton) in Wicket at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[5.12] Much like the real-world culture of Wicket's audience, the culture of Palpatine's Empire is presumed male, White, and human, and this presumption is reinforced by the legal and economic structures. Individuals who fall outside of these privileged categories do not possess the right to contradict the official story. Authority is presumed, not earned, as evidenced by the struggles of the Ensign, surrounded by White men who are constantly, literally silencing her (figure 9). Jayme Alilaw, who played the role of the Ensign, commented, "She is super smart and very ruthless, and if people would just listen to her, the Empire would win. But nobody's listening to her" (Sharp and Alilaw 2017).

Figure 9. The Ensign (Jayme Alilaw) is interrupted by an Imperial Stormtrooper in Wicket at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[5.13] The devaluation of characters such as Wicket, kept in place first by a sizeist hierarchy and again by anthropocentricism, and the Ensign, as a Black woman, reflects the devaluation of voices in the real world on the basis of class, gender, race, religion, orientation, or countless other discriminatory factors. Palpatine alone has the authority to determine "truth" for an entire galaxy. As Wicket laments, "We're still in the position / Where they own our exposition" (Sharp and Kime 2017b). In an act of rebellion, Wicket undercuts the dominant narrative, literally using the master's toys to do it. The Ewoks' ultimate resistance is pitted against a deep cultural conditioning:

[5.14] WICKET: The Emperor is so sure that we're going to step into line. And yeah, I guess normally we would, 'cause it's in the Rules.

ALL: Step in line!

WICKET: No! They crossed the line! (Sharp and Kime 2017a)

[5.15] The Rules are second nature to the Ewoks, so commonsense that they do not warrant questioning. Wicket is easy to dismiss until the threat of domination and de-"human"-ization becomes universal to all in the tribe, regardless of rank. Then their subconscious presumptions merit reexamination, and blind acceptance of the natural order of things begins to crumble. Cracks appear in the official narrative. These cracks in the hegemony, already apparent to Othered individuals, are blown apart when the privileged are forced to face them.

6. Cosplaying me

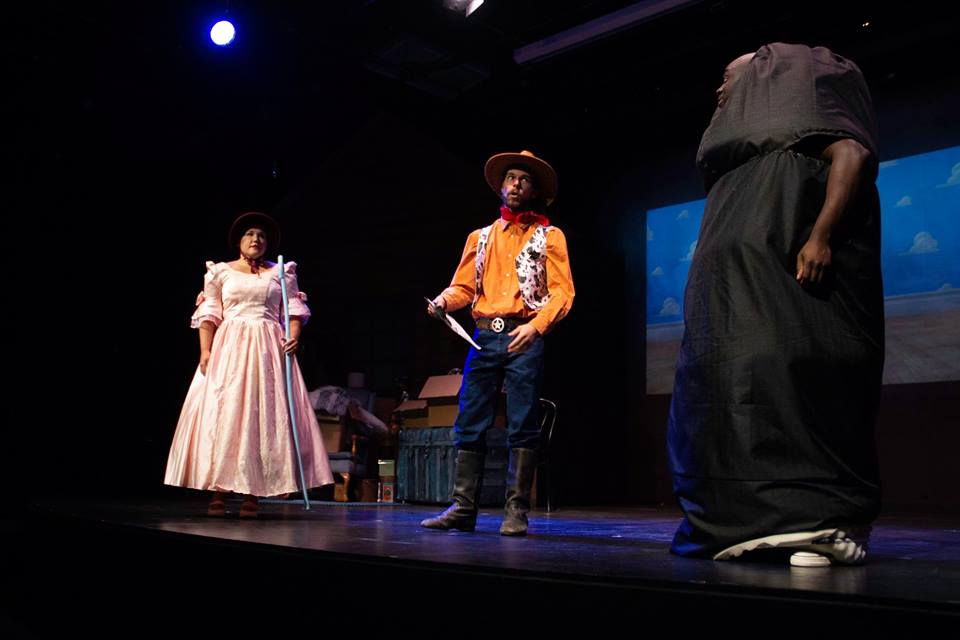

[6.1] While not overtly bothered with the legality of creative ownership, Black Nerd also shows great concern over how producers construct hegemonic narrative. The conspicuous lack of characters of color in mainstream film—even science fiction and fantasy cultures that do not reflect the racial discrimination of the real world—is a subject of hot debate and tension in fandom. At the outset of the show, Marcus confides to the audience, "In case you haven't figured it out a lot of this show is going to be dealing with race. I try not to see it but regardless of how I feel it is a major part of my life and it makes a difference. Race changes the story" (Carr 2018, 10). The play goes on to illustrate comically how race can change familiar stories from the popular canon via a series of scenes that introduce blackness into the plots of well-known films, such as: Back to the Future (1985), in which Marty/Marcus responds to Doc's fearful exclamation that his parents are in danger with an unconcerned, "Of course they're in danger. It's 19-fuckin'-55!" (figure 10); Toy Story 2 (1999), in which a black dildo—whom Andy's mom calls Idris Elba—has found himself "in the wrong box" (figure 11); and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002), when Draco Malfoy awkwardly explains that the slur "mudblood" is "not a race thing."

Figure 10. Marcus (Avery Sharpe) steps in as Marty McFly for a scene with Doc Brown (Jon Wierenga) in Black Nerd’s parody vignette of Back to the Future at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

Figure 11. Bo Peep (Mandy Butler), Sheriff Woody (Cole Wadsworth), and Marcus (Avery Sharpe) as the misplaced dildo "Idris Elba" in Black Nerd’s parody vignette of Toy Story 2 at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[6.2] These interludes, dispersed over the course of the play, draw acute attention to the fact that real-world issues of racial experience have not been taken into consideration either in the production or often in the reading of most films that generate mass fan followings and eventually find their way into the cultural canon (note 9). They also demonstrate Jenkins's point that while "changing the sexual orientation of a character has a long fannish history," by contrast "changing racial identities pushes much further against the grain" (Jenkins 2018, 388). Carr's criticism of the problems that arise at the intersection of race and geek fan culture is twofold: first, Black Nerd throws media's lack of black representation into stark relief; but second, Carr expresses through Marcus a wish that race would cease to be seen as a relevant factor.

[6.3] The desire to overcome racialization is underscored by the difficulty Marcus experiences in simply cosplaying his favorite characters, rather than mining fandoms for the few-and-far-between Black characters (note 10). When Marcus cosplays He-Man at Dragon Con (figure 12), he is bombarded with compliments that his "Black He-Man" is "hilarious" or "political" or "Urban He-Man" (note 11), while he continuously insists that he is cosplaying "JUST He-Man" (Carr 2018, 55–56). These reactions to Marcus's choice of cosplay emphasize what andré carrington refers to as "a discourse of participatory culture in which only White male audience members can enjoy the pleasures of identification" (2016, 171). Carr himself has expressed frustration with simply cosplaying his favorite characters without being perceived as making a joke or a political statement (2017).

Figure 12. Marcus (Avery Sharpe) in costume as He-Man, defending his cosplay choice to other cosplayers (Freddy Boyd, Candy Mclellan, Andrene Ward-Hammond, and Mandy Butler) in Black Nerd at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[6.4] Within the context of fan culture, minority cosplayers find themselves caught in the precarious balance between fandom's desire for celebration of source texts and desire to see themselves in those texts. Jen Gunnels and Carrie J. Cole label fan performance such as cosplay "ethnodramaturgy," comparing geek fans both to ethnographers for immersing themselves in a (fictional) culture, closely studying it and mining it for artifacts, and to dramaturgs for "link[ing] [the fragments] together in a performative story line" (2011, ¶5). Like ethnographers, geek fandoms highly value authenticity in their performances. Traditionally cosplayers have partially chosen characters based on their own body type, and while the popularity and celebration of cosplaying off body type is on the rise, the original image of a character often remains strong in the minds of other fans interpreting the performance of a cosplay.

[6.5] The concept of performing to expectations is a strong theme throughout Black Nerd. Among his family, Marcus must attempt to perform "Black," and he is reminded repeatedly that he does not talk, act, or dress "Black enough." Among his geeky friends, he is conversely reminded that his Blackness causes him to stand out and is compared and contrasted with stereotypes of Black culture. While Marcus struggles and constantly fails to fit in comfortably in either of his conflicting worlds, Marcus's Grandma refuses to fit in anywhere—including the world of the stage. Grandma constantly comments on her status as "a plot device" in "a fuckin' play" (Carr 2018, 72–73). She functions both as Marcus's greatest supporter in his nerdiness and as his Brechtian guide through the plotline of his journey to make sense and meaning of his life (figure 13).

Figure 13. Marcus (Avery Sharpe) and his Grandma (Andrene Ward-Hammond), breaking the fourth wall as she crashes her own funeral in Black Nerd at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[6.6] Metatheatricality, such as Grandma's medium awareness and Marcus's fourth wall–breaking confessional monologues, is a common device in geek theatre, used to maintain a critical distance from the fan-produced text so that (1) the author, characters, and audience can continue to actively make sense of source text and (2) the metatext provides an addition to the geek fan culture canon. In this manner, the play can reify its status as an unfinished production, a chapter in an ongoing discourse. Like other forms of fan-produced text, these plays burlesque the source material by performing fandom while critically discussing the gaps and flaws of the very things they celebrate.

[6.7] Marcus's need to find a place for self-expression is typical of fans' negotiations with the boundaries of the universes they wish to inhabit. In his moment of self-realization, he sheds his He-Man costume to take the opportunity, for once, to be himself, with no pretense or performance:

[6.8] Dragon Con is truly the one time a year we can be anything we want. We can dress as the thing we love and care about the most. We can be the version of ourselves we've always wanted to be but here's the thing, I do that every day. I put on a costume and try to act like the people in my life. But I'm terrible at it and find myself hating myself more and more with each failure. But it stops today. Today I choose my version of me. (Carr 2018, 57)

[6.9] Even this action is met with confusion by his geek peers at the con as they try to interpret what character he means when he says, "I'm cosplaying as me" (Carr 2018, 57). His refusal to perform is ultimately regarded with shock, as someone exclaims, "Oh shit. You're going IRL!" (Carr 2018, 57) (note 12). Ultimately, Marcus does not appear to have an appreciable effect on the dominant narrative structure—fiction or in real life—but he is able to find methods of navigating the narrative that allow him to resist and make his voice heard.

7. Secondary characters

[7.1] Despite difficulties within fan culture for minorities, marginalized individuals are often drawn to these universes and the characters who inhabit them because they provide alternate cultures or realities in which to navigate real-world social issues safely. Geek theatre exemplifies, as Jenkins might say, "fan critics pull[ing] characters and narrative issues from the margins" to "envision alternatives" to the hegemonic version of the story (1992, 155; 2006b, 60). Writers of fan texts tend to find the openings in the narrative that hold the greatest potential to express a marginal voice or subversive interpretation. Often fans favor characters who continue to stand out or suffer marginalization even in these fictional fantasy worlds, whether they be literally alien or simply different in a more familiar, conventional way.

[7.2] The relegation of female and minority characters to the sidelines of the story in source texts marketed to a mass audience is among fans' many frustrations with producers' treatment of story and characters. Many media texts that generate cult followings boast a diverse cast; oftentimes concepts such as diversity, egalitarianism, and meritocracy are even woven into the mission statement, such as with Star Trek. However, straight White men still tend to dominate leading roles, while female and minority characters rarely stray too threateningly far from the scripts allowed by the dominant discourse. Marcus explains this phenomenon as "the Lisa Turtle Rule":

[7.3] It is based on Lisa Turtle from Saved by The Bell…Throughout the series run they tried every relationship combination you could think of. Zach and Kelly, Zach and Jesse, Jesse and Slater, Kelly and Slater. Every combo except Lisa and…anyone. Every party and dance they went to Lisa somehow magically produced a mute black kid that we had never seen before and would never see again. She was the queen of the B story line. Zach, Kelly, Slater, and Jesse handled the A storyline while Screech and Lisa generally dealt with the B story line. It's the Lisa Turtle rule. You can do whatever you want but ultimately the story is not about you and above all you don't get the girl/guy. (Carr 2018, 21)

[7.4] Marcus and Wicket both struggle for the right to play the main character in their own respective stories. The hero rising from humble beginnings is a classic archetype; even so, these underdog-to-alphas tend to fit a very specific type. Both Black Nerd and Wicket draw attention to the fact that their protagonists are not protagonist material, that they have no place in the conventional storyline except in the margins.

[7.5] Marcus and Wicket themselves consciously recognize that in the official canonical narrative, they belong in the B-storyline. Uhura never becomes captain of a starship. No Leia prequel has graced the screen. Major films and series repeatedly depict brilliant women or minority characters who play the role of supporting the unlikely White male hero. These characters pay lip service to the ideal of equal representation, but they are not chosen to receive the hero's call of destiny. Yet fans frequently pass over the swashbuckling captain types for the secondary characters who sit behind them on the bridge, seeing themselves in the overlooked supporting cast. These characters often find themselves the subject of great scrutiny by fans, major topics of discourse within the fan community, and foregrounded in fan texts. Gunnels and Cole have argued that, as ethnodramaturgs, geek fans "seek to change attitudes and circumstances, to grant agency to those who may feel they have none" (2011). Fans seek to fulfill the promise of representation at which producers only tease, restrained from rocking the boat too much by a need to sell their storylines to a broader audience. Already legally out of bounds, most fans feel no such pressure to conform to dominant culture when producing their own texts.

[7.6] A few significant omissions from Wicket's cast jump out at even the most casual consumer of Star Wars. By far the most obvious of these are Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Darth Vader. Every human male lead seen in the movies—save only Palpatine, who must play his role as the symbolic dictator—has been removed from the narrative structure. The reversal is striking. No comment is made within the play's text regarding the absence of the movies' heroes. Instead, secondary characters are seen taking the active role in their story—characters who are aware that the power structure does not focus on their needs or experiences. Female and ethnic minority characters are so hard to come by in the original trilogy that the Ensign had to be invented wholesale in order to offer a non-White, non-male angle to the Imperial side of the story, which, as Alilaw notes, "is in and of itself a commentary" (Sharp and Alilaw 2017). The show makes light of and simultaneously reifies the real-world complexity of racialized roles and equitable casting:

[7.7] WICKET: Wow, she really is evil.

KNEESAA: Yeah, but she's inclusive, so…

THE ENSIGN: No, uh-uh—don't do that! Do not typecast me. (Sharp and Kime 2017a)

[7.8] To the end, the Ensign exemplifies an egalitarian ideal, refusing to be defined as the token Black woman in the cast, practically daring the theatrical community to pat itself on the back for its perceived progressiveness in acknowledging her merits or even her existence.

[7.9] Among Wicket's cast, the Ensign best embodies the suppression of minority voices, both for her race and her gender. Not only is she ignored by her peers and superiors, but every time throughout the show when she attempts to express herself in song, she is cut off and shut down by a White male. Only in the musical's eleven-o'clock number, an operatic aria (figure 14), does she spectacularly give the middle finger to the system's "fucking bullshit rules" that, as she illustrates, devalue all but the most hegemonically privileged of voices and ideas (Sharp and Kime 2017b). On the character's vocal liberation, Alilaw says, "Opera is this genre where you don't use microphones; it's all about the power of the human voice. And so that it's so significant that she's been silenced and suppressed for all of this time, to where she finally lets it out, she lets it all out" (Sharp and Alilaw 2017) (note 13). The metaphorical as well as literal potency of the Ensign's voice underscores the rebellion of Wicket's narrative toward the mainstream point of view.

Figure 14. The Ensign (Jayme Alilaw) sings her operatic aria in Wicket at Dad's Garage Theatre Company. Photograph by Little Phish Foto.

[7.10] In Black Nerd, Grandma disrupts the narrative structure from her first entrance. Not only does she constantly remind the audience that they are watching a play, but she also refuses to be bound by Marcus's own attempts to define himself on other people's terms. She accosts him in his self-pity, interrupts his time-outs when he confides in the audience, and walks in on her own eulogy to set the record straight. Most significantly, she states the obvious: "This ain't my story. If it was it would be much sexier…This is your nerdy-ass story" (Carr 2018, 73). She rejects Marcus's willingness to be upstaged in his own narrative simply because his narrative does not fit the dominant culture's conception of an A-storyline. Fan narratives do not merely foreground marginal characters; instead, narrative structures are reconceived entirely to serve the needs of individuals whose interests are overlooked by producers merely trying to construct a marketable product. In these alternate narratives, the values governing the script can change both the cast and the story.

[7.11] While the characters of both Wicket and Black Nerd identify themselves as secondary characters in the dominant narrative, they ultimately refuse to be relegated to the margins. Instead, like geek fans, they traverse the boundaries and disrupt the narrative, quintessentially singing:

[7.12] I have something to say.

I have my story too—

A big epic saga that I can convey

From my own little Ewok point of view! (Sharp and Kime 2017b)

[7.13] Geek audiences become producers of fan texts in order to voice the unheard, to find a forum in which they can tell the stories and address the issues that mainstream culture will not.

8. Conclusion

[8.1] Between the humor and obscure geek references, these texts articulate a call to action. The call is sounded in two directions, imploring (1) individuals of all backgrounds to make their stories heard in their own voices, and (2) the privileged—whether media producers or world leaders or cis straight White men—to do a better job listening. However, at its core, geek theatre is "dialogic rather than disruptive," as Jenkins would say, "and collaborative rather than confrontational" (2006a, 150). Marcus expresses no desire to overturn the system—merely to have a recognized place in it. He ultimately rejects the need to fit in, swearing, like Grandma, to be "undefinable," opening himself to potentials he could not recognize while performing a role.

[8.2] Meanwhile, in the conclusion of Wicket, even the dictator himself discovers unimagined alternatives when prescribed definitions are defied. Emperor Palpatine does not meet the same inglorious end depicted in Return of the Jedi (1983). Instead, though still dead, he grows in his understanding, realizing as a Force-ghost in the consummation of his homoerotic interspecies love with Logray: "my creation also created me" (Sharp and Kime 2017b). Thus, the villains are graced with a slashed happy ending. As the hegemony crumbles, potentials are revealed that the hierarchy denies even to those who are most privileged.

[8.3] Yet the nature of the narrative is flexible, open to individual interpretation and, to some extent, revision. Wicket and Black Nerd exemplify how even the most secondary of characters might reshape narrative in their own image. Geek theatre opens up the alternative possibilities overlooked by the privileged elite accustomed to the "right" of narrative control.